Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Riding With The Devil: Exhibition

Uploaded by

NetaniaLimOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Riding With The Devil: Exhibition

Uploaded by

NetaniaLimCopyright:

Available Formats

Exhibition ‘Witches’ at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art

Riding with the Devil

Viv Lawes discovers the dark allure of the first major British exhibition on witchcraft

E

YES wild with malevo-

lence, every tendon in her

emaciated body straining

in the raking firelight of the night

sky, Invidia, hair full of serpents,

eats her own heart out. Envy is an

old woman, a hideous hag whose

breasts, no longer capable of giving

succour to an infant, are objects

of revulsion. These symbols of

femininity, no longer useful, have

become symbols of evil.

These are the thoughts that

sprang to mind when artist and

writer Deanna Petherbridge, guest

curator of this groundbreaking

exhibition, saw Jacques de Gheyn’s

1596 print Invidia more than

a decade ago. She was, at the time,

researching her 2010 publication,

The Primacy of Drawing. ‘I kept

realising that, every time I came

across these hideous depictions

of old women as the personifi-

cation of Envy, they were incredibly

similar to the representation of

witches, who are motivated by

envy. Their bodies are marked:

written upon them is the notion

that ugliness is evil. Medieval texts

are full of statements that clearly

say that, once the female body is

no longer fertile, it becomes foul.’

Miss Petherbridge’s obser-

vation grew into a chapter for

her book and now this major

survey of the depiction of witches

and witchcraft—the first of its

kind at a major British institution.

The exhibition spans 500 years

of western art, beginning in the

late 15th century with Dürer and

ending with contemporary artists

such as Paula Rego and Kiki Smith,

the imagery of successive centuries

traced through Francisco de Goya,

William Blake and John William

Waterhouse. It is divided thematic-

ally to include witches’ various

incarnations, their supposed prac-

tices and the theatrical tradition

that has grown up around them.

Thus we see the old hag juxta-

posed with the seductive sorceress;

the Sabbaths and devilish rituals;

unnatural acts of flying; magic

circles, spells and the raising of The Magic Circle by John William Waterhouse, 1886—magic is a common theme in the artist’s work

80 Country Life, July 31, 2013 www.countrylife.co.uk

JUL 31 EXHIBITION FINAL.indd 80 25/07/2013 12:40

The dominance of prints and The imagery and textual sources

drawings shows the way in which supported the social, political

the notion of witchcraft and the and religious complexities that

widespread belief in its existence breathed life into the persecution

was connected to the development of anyone who didn’t fit the sup-

of printing, says Miss Pether- posed norms or engendered fear:

bridge. Malleus Maleficarum— old women, supernaturally beauti-

the 1486 publication that became ful women, midwives, Jews, poets,

the handbook for the persecution gypsies. ‘The strangest thing is

of witches, resulting in the deaths that the imagery of witchcraft

of up to nine million people, from one end of Europe to

mainly women, over 250 years— another was disquietingly simi-

owed its fame to the printing press. lar—the presence of fire, flying

Likewise, engravings and wood- backwards, unnatural sexual acts.

cuts on the subject were widely Everything was an inversion of

circulated from an early date: the Christian iconography,’ says Miss

survival of multiple versions of Petherbridge. ‘Imagery and lan-

Dürer’s Witch Riding Backwards guage was borrowed, reproducing

on a Goat, 1500, and Hans Bal- and restructuring ideas.’

dung Grien’s Witches’ Sabbath, The high profile of this exhi-

1510—a chiaroscuro double-block bition as it opened in time for

woodcut print that looks like the Edinburgh Festival suggests

a highly polished carved relief— that these ideas still have a dark

are testament to their popularity. allure.

A century later, at the peak of ‘Witches & Wicked Bodies’ is at

the witch trials in Europe, another the Scottish National Gallery

of Jacques de Gheyn’s prints, Prep- of Modern Art (Modern Two),

aration for a Witches’ Sabbath, Edinburgh until November 3

1610, was so widely circulated (www.nationalgalleries.org;

that it influenced books and the 0131–624 6560)

Invidia (Envy), engraving by Z Dolendo after Jacques de Gheyn II broadsheets that were printed

every time a trial took place. Next week: Mary Queen of Scots

corpses; and unholy trinities and a handful of paintings loaned from

the sisterly witches of Macbeth. British institutional and private

We also see their representation collections. Monochrome graphic

by modern and contemporary art- imagery sweeps through the gal-

ists, which has resonance in an lery; this is interrupted occasion-

Tate, London; National Galleries of Scotland; Trustees of the British Museum, London

increasingly secular West, where ally by splashes of colour that

adherents of the Wicca movement emerge in works such as Salvator

tenaciously promote witchcraft Rosa’s masterpiece Witches at

as a form of nature worship. their Incantations, 1646, and

The majority of the 86 works on Frederick Sandys’s sumptuous pre-

show are prints and drawings, with Raphaelite Medea, 1866–68.

Unholy trinities: The Night of Enitharmon’s Joy (formerly called

The Triple Hecate) by William Blake, about 1795 Woman Bewitched by the Moon No. 2 [Opus 0.175], Alan Davie, 1956

www.countrylife.co.uk Country Life, July 31, 2013 81

JUL 31 EXHIBITION FINAL.indd 81 25/07/2013 12:46

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without

permission.

You might also like

- Scott Morrison Says The Colony of New South Wales Was Founded On The Basis There Would Be No Slavery. Is He Correct - ABC NewsDocument5 pagesScott Morrison Says The Colony of New South Wales Was Founded On The Basis There Would Be No Slavery. Is He Correct - ABC NewsNetaniaLimNo ratings yet

- Adr - Argument For and Against Use of The Mediation Process Particularly in Family and Neighbourhood DisputesDocument16 pagesAdr - Argument For and Against Use of The Mediation Process Particularly in Family and Neighbourhood DisputesNetaniaLimNo ratings yet

- Buffalo in The Gilded AgeDocument20 pagesBuffalo in The Gilded AgeNetaniaLimNo ratings yet

- World Malaria Report 2022Document372 pagesWorld Malaria Report 2022NetaniaLimNo ratings yet

- Should Your Club IncorporateDocument2 pagesShould Your Club IncorporateNetaniaLimNo ratings yet

- Delivery of Advice To Marginalised and Vulnerable Groups: The Need For Innovative ApproachesDocument29 pagesDelivery of Advice To Marginalised and Vulnerable Groups: The Need For Innovative ApproachesNetaniaLimNo ratings yet

- Justice Quality and Accountability in Mediation Practice: A ReportDocument52 pagesJustice Quality and Accountability in Mediation Practice: A ReportNetaniaLimNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court of Victoria: Practice Note SC Gen 5 Technology in Civil LitigationDocument20 pagesSupreme Court of Victoria: Practice Note SC Gen 5 Technology in Civil LitigationNetaniaLimNo ratings yet

- Legal Fairness in ADR Processes - Implications For Research and TeachingDocument9 pagesLegal Fairness in ADR Processes - Implications For Research and TeachingNetaniaLimNo ratings yet

- NEOQUE Issue01 EnglishDocument53 pagesNEOQUE Issue01 EnglishNetaniaLimNo ratings yet

- The Vietnam Era Antiwar Movement: Mitchell K. HallDocument6 pagesThe Vietnam Era Antiwar Movement: Mitchell K. HallNetaniaLimNo ratings yet

- Modernismandthe Commonwriter : F 2005 Cambridge University PressDocument19 pagesModernismandthe Commonwriter : F 2005 Cambridge University PressNetaniaLimNo ratings yet

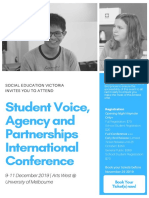

- Student Voice Conference SVC 2019Document2 pagesStudent Voice Conference SVC 2019NetaniaLimNo ratings yet

- International Law ExamDocument5 pagesInternational Law ExamNetaniaLimNo ratings yet

- YELL IRAC Method Example For EssayDocument10 pagesYELL IRAC Method Example For EssayNetaniaLim100% (1)

- Davey and Legg On EdiscoveryDocument3 pagesDavey and Legg On EdiscoveryNetaniaLimNo ratings yet

- Alexis FrenchDocument9 pagesAlexis FrenchNetaniaLimNo ratings yet

- Copywriting 101Document55 pagesCopywriting 101NetaniaLim100% (3)

- Valse Sentimental No. 1 Eric ChristianDocument2 pagesValse Sentimental No. 1 Eric ChristianNetaniaLim87% (15)

- Shostakovich-Romance From The Gadfly-SheetMusicDocument1 pageShostakovich-Romance From The Gadfly-SheetMusicNetaniaLimNo ratings yet

- Addams FamilyDocument5 pagesAddams FamilyNetaniaLimNo ratings yet

- MilnerReview PDFDocument19 pagesMilnerReview PDFNetaniaLimNo ratings yet

- Folks Who Live On The HillDocument5 pagesFolks Who Live On The HillNetaniaLimNo ratings yet

- You Are The Reason - Callum ScottDocument4 pagesYou Are The Reason - Callum ScottNetaniaLim100% (6)

- Folks Who Live On The HillDocument5 pagesFolks Who Live On The HillNetaniaLimNo ratings yet

- John Ireland Amberley Wild BrooksDocument6 pagesJohn Ireland Amberley Wild BrooksNetaniaLimNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- AMIGA - Bloodwych ManualDocument5 pagesAMIGA - Bloodwych ManualjajagaborNo ratings yet

- Kitchen Witchin'Document3 pagesKitchen Witchin'vincentpagan1No ratings yet

- BooksDocument5 pagesBookslgarcoa100% (1)

- The Occult SciencesDocument409 pagesThe Occult SciencesIan ThomsonNo ratings yet

- Harry Potter Nightmares of Futures PastDocument286 pagesHarry Potter Nightmares of Futures Pastrthomas2100% (1)

- Herbs, Roots & MineralsDocument21 pagesHerbs, Roots & MineralsFiery Pathfinder100% (5)

- Character Class: The AugererDocument1 pageCharacter Class: The AugererhigherdepthsNo ratings yet

- Harry Potter TerminologyDocument2 pagesHarry Potter TerminologyPeter BacomoNo ratings yet

- Misc. Magickal LoreDocument164 pagesMisc. Magickal LoreMelissaNo ratings yet

- Secrets Nine CovensDocument9 pagesSecrets Nine CovensMephisto Ben AzhiNo ratings yet

- Hero Quest 2 Supplemental RulesDocument20 pagesHero Quest 2 Supplemental RulesJeremy Griffith100% (1)

- Humble PieDocument393 pagesHumble PiecoraNo ratings yet

- Demons, Devils and Djinn by Olga HoytDocument164 pagesDemons, Devils and Djinn by Olga HoytDebby Luppens100% (16)

- Abramelin The Mage - Liber Samekh Theurgia Goetia Summa Congressus Cum Cd2 Id2115495242 Size65Document6 pagesAbramelin The Mage - Liber Samekh Theurgia Goetia Summa Congressus Cum Cd2 Id2115495242 Size65Dejan Matasić100% (1)

- Folk Magic and Protestant Christianity in AppalachiaDocument35 pagesFolk Magic and Protestant Christianity in AppalachiaViktorija Briggs100% (5)

- The Rite of The Spider GoddessDocument8 pagesThe Rite of The Spider Goddesspajemalfoy100% (3)

- A Warrior's LifeDocument19 pagesA Warrior's LifeEnergeneticWarrior SevenCrowNo ratings yet

- FaeriesDocument26 pagesFaeriesclotho19No ratings yet

- GrimoireDocument46 pagesGrimoireNeyana Zsuzsa Parditka100% (1)

- Ancient Grimoires Pulp Fiction or Magical Guides? IGOSDocument22 pagesAncient Grimoires Pulp Fiction or Magical Guides? IGOSIntergalactic Guild of Occult Sciences - Extreme Futuristic Occultism67% (9)

- Peter Haining - The Warlocks Book PDFDocument111 pagesPeter Haining - The Warlocks Book PDFjason84% (25)

- NERO CosmlogyDocument25 pagesNERO CosmlogyFarva MoidNo ratings yet

- Nation - AlftiariaDocument2 pagesNation - AlftiariaZachary J. AdamNo ratings yet

- Golden Dawn - Lesser Banishing Ritual of The HexagramDocument3 pagesGolden Dawn - Lesser Banishing Ritual of The HexagramMarco PauleauNo ratings yet

- Cloak&Dagger For LL 1.01Document6 pagesCloak&Dagger For LL 1.01w@argameNo ratings yet

- Grandfather BakhyeDocument3 pagesGrandfather Bakhyeapi-301446739No ratings yet

- Direction - Further Reflections On Paul Hiebert's "The Flaw of The Excluded Middle"Document20 pagesDirection - Further Reflections On Paul Hiebert's "The Flaw of The Excluded Middle"eltropicalNo ratings yet

- Bibliography of Mesopotamian MagicDocument4 pagesBibliography of Mesopotamian MagicTalon BloodraynNo ratings yet

- De Magia Naturali and Quincuplex Psalterium by Jacques Lefèvre D'étaples: Kabbalah As Biblical MagicDocument11 pagesDe Magia Naturali and Quincuplex Psalterium by Jacques Lefèvre D'étaples: Kabbalah As Biblical MagicKathryn LaFevers EvansNo ratings yet

- The Satanic Spiritual Schism - Anamorphosis, Transcendental Meditation, Astral Projection and The Third EyeDocument2 pagesThe Satanic Spiritual Schism - Anamorphosis, Transcendental Meditation, Astral Projection and The Third EyeAleister Nacht50% (4)