Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Academic Performance of College Students Influence

Uploaded by

Melissa AguilarCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Academic Performance of College Students Influence

Uploaded by

Melissa AguilarCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/254344820

Academic Performance of College Students: Influence of Time Spent Studying

and Working

Article in The Journal of Education for Business · January 2006

DOI: 10.3200/JOEB.81.3.151-159

CITATIONS READS

123 21,470

2 authors:

Sarath A. Nonis Gail I. Hudson

Arkansas State University - Jonesboro Arkansas State University - Jonesboro

37 PUBLICATIONS 1,022 CITATIONS 15 PUBLICATIONS 406 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

All content following this page was uploaded by Gail I. Hudson on 06 August 2014.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Academic Performance of College

Students: Influence of Time Spent

Studying and Working

SARATH A. NONIS

GAIL I. HUDSON

ARKANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY

JONESBORO, ARKANSAS

ABSTRACT. Today’s college students

are less prepared for college-level work T oday’s college students are spend-

ing less time studying. The fall

2003 survey conducted by the Higher

dents (Smart, Tomkovick, Jones, &

Menon, 1999). The 2002 survey con-

ducted by the Higher Education

than their predecessors. Once they get to

Education Research Institute at Research Institute also found that

college, they tend to spend fewer hours UCLA’s Graduate School of Education 65.3% of entering freshmen have either

studying while spending more hours work- and Information Studies found that “some concern” or “major concerns”

ing, some even full time (D. T. Smart, C. A. only 34% of today’s entering freshmen about not having enough money to com-

have spent six or more hours per week plete their college degrees (Higher Edu-

Kelley, & J. S. Conant, 1999). In this study,

outside of class on academic-related cation Research Institute, 2002). This

the authors examined the effect of both work (e.g., doing homework, studying) was an increase of almost 1% from

time spent studying and time spent working during their senior year in high school. 2001 and is likely to increase in the

on academic performance. The authors fur- The sample consisted of 276,449 stu- years ahead because of reduced funding

dents at 413 of the nation’s 4-year col- for higher education by state legisla-

ther evaluated the interaction of motivation

leges and universities (over one fourth tures. Although more women (70.9%)

and ability with study time and its effect on of entering freshmen in the United were concerned about whether they

academic performance. The results suggest- States), and the data were statistically would have enough funds to complete

ed that nonability variables like motivation adjusted to reflect responses of all first- college than were men (58.3%), all stu-

time, full-time students entering all dents seemed to be working out of the

and study time significantly interact with

four-year colleges and universities as need to make up for rising tuition and

ability to influence academic performance. freshmen in 2003. In fact, in 1987 when fewer available grants. In summary, the

Contrary to popular belief, the amount of this question was asked of entering proportion of college students who are

time spent studying or at work had no freshmen, 47.0% claimed they spent 6 employed either part or full time is like-

or more hours per week studying out- ly to increase in the years to come, leav-

direct influence on academic performance.

side of class. Since then, the time spent ing greater numbers of students with

The authors also addressed implications studying outside of class has declined less time for academic work.

and direction for future research. steadily each year (Higher Education Students spending less time studying

Research Institute, 2003). and more time working are two trends

Another trend that is emerging is the that all colleges and universities will have

Copyright © 2006 Heldref Publications

increase in the number of college stu- to confront. Lowering academic stan-

dents who are employed either part time dards by rewarding minimum effort and

or full time. According to Gose (1998), achievement (expecting less) is certainly

39% of college freshmen work 16 or a short-term strategy, but one that will

more hours per week, an increase of 4% have negative long-term consequences. A

since 1993. Among all business majors, more productive way to handle these con-

marketing students typically work even cerns is to conduct empirical research to

more hours per week than do other stu- determine to what extent these trends will

January/February 2006 151

negatively impact the academic perfor- (1991) found that the study habits of 1991; Nonis & Wright, 2003; Wright &

mance of college students and use the freshmen relate significantly to their first Mischel, 1987), performance is a multi-

findings from these studies to improve year cumulative grade point average plicative function of both ability and

our academic programs. (GPA). In their investigation of 143 col- motivation.

The influence that personal variables, lege students, McFadden and Dart

Performance = Ability × Motivation

such as motivation and ability, have on (1992) reported that total study time

academic success is well documented, influenced expected course grades. In For example, a student with very high

but there is a paucity of research inves- contrast, Mouw and Khanna (1993) did ability but low motivation is unlikely to

tigating the influence that time college not find study habits to significantly perform well, whereas a student with

students spend on various activities improve the explanatory power of the low ability but high motivation is likely

such as studying outside of class and first year cumulative GPA of college stu- to perform well. That is, the variability

working has on their academic success. dents. Ackerman and Gross (2003) have in motivation across students may

One reason for a lack of research in this found more recently that students with dampen associations between ability

area may be the common belief among less free time have a significantly higher and performance.

most students and academicians that GPA than those with more free time. In the same vein, one can argue that

more time spent studying outside of Because of this conflicting evidence, it is simply the study behavior that ulti-

class positively influences academic there is a need to reinvestigate this rela- mately brings about the desired perfor-

performance and that more time spent tionship. Thus, our first hypothesis was mance and not students’ inner desires or

working negatively influences academic H1: There is a relationship between time motivations. This is supported by the

performance. Another, more plausible spent studying outside of class and aca- widely held belief that it is hard work

reason for this lack of research may be demic performance. (i.e., time spent on academic activities

the complex nature of these relation- Along with the present trend of stu- outside of class by a student) that

ships when evaluated in the presence of dents spending less time on academic- results in academic success and that

other variables, such as student ability related activities, a growing number of laziness and procrastination ultimately

and motivation. For example, it is likely college and university administrators are result in academic failure (Paden &

that time spent studying outside of class concerned that today’s postsecondary Stell, 1997). Therefore, similar to how

will have a differential impact on the students are working more hours than motivation interacts with ability to

academic performance of college stu- their counterparts were years ago (Gose, influence academic performance, one

dents who vary in ability. That is, the 1998). It can be reasonably assumed that can infer that behavior such as hard

relationship that ability has with student working more hours per week will leave work interacts with ability to influence

performance will be stronger for those students less time for studying outside of performance among college students.

students who spend more time outside class and that this will negatively influ- This led us to our third hypothesis to be

of class studying than for students who ence their academic performance. tested in this study.

spend less time studying. Although working more hours per week H3: Behavior (time spent studying out-

With this study, we attempted to fill can be one key reason for a student to be side of class) will significantly interact

this void in the literature. First, we in academic trouble, available research with ability in that the influence that abil-

attempted to determine the direct rela- does not seem to support this hypothesis. ity has on academic performance will be

tionship that time spent on academics higher for students who spend more time

Strauss and Volkwein (2002) reported studying outside of class than for students

outside of class and working had on aca- that working more hours per week posi- who spend less time studying.

demic performance among business stu- tively related to a student’s GPA. Light

dents. Second, we attempted to deter- (2001), who interviewed undergraduate All indications are that today’s college

mine whether the time spent on students of all majors, found no signifi- freshmen are less prepared for college

academics outside of class interacts with cant relationship between paid work and than their predecessors. American Col-

variables, such as student ability and grades. According to Light, “students lege Testing (ACT) Assessment reports

motivation, in influencing the academic who work a lot, a little, or not at all share that fewer than half of the students who

performance of business students. a similar pattern of grades” (p. 29). take the ACT are prepared for college.

Because empirical evidence to date has According to the Legislative Analyst’s

Hypotheses Tested been counterintuitive, testing this Office (2001), almost half of those stu-

hypothesis using different samples and dents regularly admitted to the California

It is commonly believed that students different methodologies is important State University system arrive unpre-

who spend more time on academic- before generalizations can be made. This pared in reading, writing, and mathemat-

related activities outside of class (e.g., led to our next hypothesis that ics. Although these statistics are common

reading the text, completing assign- at most colleges and universities in the

ments, studying, and preparing reports) H2: There is a relationship between time nation, how institutions handle these

spent working and academic performance.

are better performers than students who concerns varies. Strategies include

spend less time on these activities. There According to Pinder (1984) and oth- attempting to develop methods to diag-

is some empirical support for this belief. ers (Chan, Schmitt, Sacco, & DeShon, nose readiness for college-level work

For example, Pascarella and Terenzini 1998; Chatman, 1989; Dreher & Bretz, while students are still in high school or

152 Journal of Education for Business

requiring remedial courses of entering This timing was deliberate because Achievement Striving

freshmen, thereby lowering academic data were being collected for the moti-

We used six items from a Spence et

standards. vation variable, one that is likely to

al. (1987) Likert-type 1–5-point scale,

There are others who believe that it is change among students during the

to measure students’ achievement striv-

not only reading, writing, and mathemat- early and late parts of a semester. In

ing, which we used as a surrogate for

ics abilities that influence academic per- addition, information on such variables

motivation. In several prior studies,

formance, but also nonability variables, as time spent on academics or work-

researchers have used this variable as a

such as motivation (Barling & Charbon- related activities is also likely to vary

measure of motivation (Barling & Char-

neau, 1992; Spence, Helmreich, & Pred, during the beginning, middle, and end

bonneau, 1992; Barling, Kelloway, &

1987), self-efficacy (Bandura & Schunk, of a semester.

Cheung, 1996). The reported coefficient

1981; Multon, Brown, & Lent, 1991; We distributed surveys and explained

alpha for this scale is high (0.87), and

Zimmerman, 1989), and optimism them to those students who participated

this scale has been used in several other

(Nonis & Wright, 2003). Although a in the study. The survey consisted of

similar studies (Carlson, Bozeman,

minimum level of ability is required, it is two parts. The first part required stu-

Kacmar, Wright, & McMahan, 2000;

plausible that nonability variables will dents to maintain a journal during a 1-

Nonis & Wright, 2003).

compensate for ability inadequacies to week period, documenting how much

bring about the required level of perfor- time they spent on various activities

Demographic Variables

mance. One question that interests all each day of the week (there were over

parties is whether hard work (i.e., more 25 activities listed under three broad Students reported demographic infor-

time spent studying) will influence the categories: academics, personal, and mation, such as gender, age, and racial

relationship between motivation and per- work related). For accuracy purposes, or ethnic group membership, in their

formance. That is, will the relationship we asked students to complete their journals.

between motivation and academic per- journal each morning, recording the

formance be stronger if a student puts previous day’s activities. The second Behavior Variables

more effort or time into studying outside part of the survey contained demo-

We also used student journal data to

of class compared with those who put in graphic information, such as gender,

determine the time spent outside of

less time? This led to our final hypothe- age, and race, as well as measures of

class on academic activities like reading

sis, one that was speculative in nature, several other constructs including moti-

the text and lecture notes for class

but nevertheless has implications for vation (only motivation was used in this

preparation, going over the text and lec-

both students and academicians. study). Participants had to provide their

ture notes to prepare for exams, and

H4: Behavior (more time spent studying social security numbers for documenta-

completing assignments and homework.

outside of class) will significantly interact tion purposes. We assured them that

The researcher added these items for the

with motivation in that the influence that their responses would be pooled with

motivation has on academic performance week to derive the total amount of time

others and no effort would be made to

will be higher for students who spend students spent outside of class on aca-

evaluate how any one individual may

more time studying outside of class com- demic activities during the week (TSA).

pared with students who spend less time have responded to the survey. We urged

Students also reported the time they

studying outside of class. students to take the task seriously and

spent working, as well as the time it

to be accurate in their responses to each

took for them to travel to and from work

question. A cover letter signed by the

METHOD each day, during the given week. These

dean of the college of business was

two items were also added to derive the

included in each student’s journal. We

Sample total amount of time students spent

administered 440 surveys, and 288

working during a given week (TSW).

We secured the data for this study were returned. Two hundred and sixty-

from a sample of undergraduate stu- four of the returned surveys were

Analysis

dents attending a medium-sized usable, yielding an effective response

(10,000+), Association to Advance rate of 60.0%. As Table 1 shows, sample character-

Collegiate Schools of Business istics were comparable to available

(AACSB)-accredited, public university Measures demographic characteristics of college

in the mid-south United States. To students in the United States (Statistical

obtain a representative sample of all We used the social security numbers Abstract of the United States, 2002).

students, we selected classes from a provided by the respondents to collect Other pertinent demographic character-

variety of business courses (e.g., man- university data for the variable grade istics for the sample were as follows:

agement, accounting, MIS, finance) point average for the semester (SGPA), average age = 23.8 years; majors = 16%

,offered at various levels (freshmen, semester courseload, number of hours accounting, 13.1% business administra-

sophomore, junior, and senior) and at completed to date, and ACT composite tion, 12.3% finance, 13.5% manage-

different times (day or night), for the score. As such, these variables were not ment, 14.5% marketing, 14.5% MIS,

study. Data collection occurred during self-reported and should provide more and the remainder “other” business

the 9th week of a 15-week semester. validity to the study’s findings. majors.

January/February 2006 153

We coded gender and racial or ethnic strated an acceptable reliability coeffi- demic load was also included as a con-

group membership and used them as cient as per Nunnally (1978). trol variable because students who take

dummy variables consisting of two cat- Prior to testing the hypotheses, it was more courses are likely to spend more

egories (coded 0 or 1), such as male or important for us to control for variables time studying outside of class compared

female and African American or other, that were likely to have an impact on with students who take fewer courses.

because 97.5% of the sample was either academic performance other than the In addition, we treated TSA and TSW as

Caucasian or African American. To variables that we were testing. Studies independent variables, and we used

determine the bivariate relationships have found that demographic variables, SGPA as the dependent variable.

that the plausible predictor (indepen- such as gender, age, and race (Cubeta, We tested moderator relationships

dent) variables had with the academic Travers, & Sheckley, 2001; Strauss & proposed in H3 and H4 through moder-

success (dependent) variables, we cal- Volkwein, 2002), influence the academ- ated multiple regression analysis

culated Pearson’s product moment cor- ic performance of college students. (Cohen & Cohen, 1983; Wise, Peters, &

relation coefficients. Table 2 shows both Therefore, we tested H1 and H2 using O’Conner, 1984). We performed three

the descriptive statistics and the Pear- partial correlation coefficients, control- regressions: (a) We regressed the depen-

son’s correlation coefficients. The ling for the extraneous variables gender, dent variable (SGPA) on the control

achievement-striving measure demon- age, and racial or ethnic group. Aca- variables (gender, age, racial or ethnic

group membership, and academic load);

(b) we regressed the dependent variable

TABLE 1. Demographic Characteristics of the Sample Compared With the on the control variables, plus the inde-

Population, in Percentages pendent variable (i.e., ACT composite

score as a surrogate for ability), plus the

Demographic characteristic Populationa Sample

moderator variable (i.e., TSA as a surro-

gate for hard work or behavior); and (c)

we regressed the dependent variable on

Gender

Male 43.6 44.2 the control variables, plus the indepen-

Female 56.3 55.8 dent variable, plus the moderator vari-

Racial/Ethnic Group able, plus the interaction (i.e., ACT

White 77 85 composite score and TSA).

African American 12.1 12

The process involved conducting

Other 11 2.5

Employment Status three regression models for each mod-

Do not work 35.6 34 erator hypothesis. This process facili-

Work part time 30.3 28 tated the investigation of a potential

Work full time 34.1 37 direct influence of the moderator vari-

ables (when they serve as predictors)

Note. The sample consisted of undergraduate students enrolled in business courses at a medium- and the extent to which the posited

sized, Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business-accredited public university in the

mid-south. moderator influence actually exists.

a

Based on Statistical Abstract of the United States (2002). When both the independent and the

moderator variable are continuous

TABLE 2. Descriptive Statistics and Pearson Product–Moment Correlations for Study Variables

Variable M SD 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

1. Gender — — —

2. Age 23.76 6.29 –0.04 —

3. Race — — 0.04 –0.07 —

4. ACT composite (ACT) 22.00 3.91 –0.01 –0.24* 0.31* —

5. Achievement striving (AST)a 3.53 0.71 –0.17* 0.21* –0.09 –0.02 —

6. Time spent outside of class on

academic activities (TSA) vs.

academic load 12.94 8.57 –0.07 0.34* –0.16 –0.18* 0.29* —

7. Time spent working (TSW) vs.

academic load 16.84 14.55 0.03 –0.03 0.06 –0.03 –0.16* –0.06 —

8. Semester grade point average

(SGPA) 2.97 0.76 –0.11 –0.09 0.27* 0.45* 0.35* 0.05 –0.10 —

a

reliability coefficient = 0.77.

*p < .05 (one-tailed).

154 Journal of Education for Business

(ACT composite and TSA), as in this ses and used z scores when testing expected direction, but not significant.

study, the appropriate statistical proce- hypotheses. Therefore, H1 was not supported. The

dure to detect interaction is the moder- partial correlation coefficient between

ated multiple regression analysis (Bar- RESULTS TSW and SGPA (r = −.08, p = .28) was

ron & Kenny, 1986). also statistically insignificant, failing to

Because the measurement units asso- The partial correlation coefficient support H2.

ciated with the various scales used in between TSA and SGPA, controlling for Moderated Multiple Regression

this study were different, we standard- the variables gender, age, race, and aca- (MMR), controlling for gender, age,

ized variables investigated in the analy- demic load (r = .10, p = .19), was in the race, and academic load, provided the

statistics required to test the remaining

two hypotheses. For H3, the R2 for the

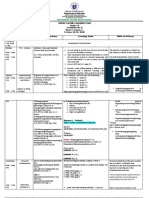

TABLE 3. Results of Moderated Multiple Regression Analysis of Time control variables was statistically signif-

Spent Outside of Class on Academic Activities (TSA), ACT Composite icant (R2 = .06, p < .05). In the second

Score (ACT), and Semester Grade Point Average (SGPA)

step, the increment to R2 was statistical-

ly significant for the addition of the

Independent variable Slope SE t p R2 main effects of ACT composite and

TSA (∆R2 = .19, p < .05). In fact, the

Control (Step 1) .06* main effects of both ACT composite and

Gender –0.12 0.13 –0.90 .36 TSA were also significant (p < .05).

Age 0.03 0.10 0.26 .78

Race 0.70 0.22 3.22 .00* From Step 2 to Step 3, the increment of

Academic load 0.05 0.07 0.74 .46 R2 was also significant for the addition

Predictor (Step 2) .25* of the interaction term (∆R2 = .03, p <

ACT composite (ACT) 0.43 0.07 6.60 .00* .05); this supported H3, which stated

Time studying (TSA) 0.17 0.07 2.54 .01* that TSA would interact with ability

Moderator (Interaction) (Step 3) .28*

ACT × TSA 0.18 0.07 2.69 .01* (see Table 3). Predicted values generat-

ed from the regression equation that

*p < .05. were one standard deviation above and

below the mean for ACT composite

score and TSA indicated that students

who were high in ACT composite and

TSA most likely had a very high semes-

ter GPA (y-hat or predicted value =

3.95), relative to students high in ACT

TSA (High) composite score with low TSA (y-hat =

3.1) and relative to students low in ACT

composite with either high (y-hat = 2.5)

or low (y-hat = 2.7) TSA. This is the

appropriate technique to interpret inter-

action terms when moderated multiple

regression is implemented (Cleary &

SGPA

TSA (Low) Kessler, 1982; Cohen & Cohen, 1983).

Results are shown in Figure 1.

For H4, the R2 for the control variables

was once again statistically significant

(R2 = .10, p < .05). In the second step, the

increment to R2 was statistically signifi-

cant (∆R2 = .14, p < .05) for the addition

of the main effects of achievement striv-

ing and TSA. However, the main effect

of TSA was not statistically significant.

LOW HIGH From Step 2 to Step 3, the increment of

ACT

R2 was also not statistically significant

(∆R2 = .01, p > .05) for the addition of

FIGURE 1. Time spent studying (TSA) and ACT composite score (ACT) the interaction term. These results did not

interaction on semester grade point average (SGPA). Graph is based on provide support for H4, which stated that

predicted values (y-hat) generated from the regression equation for indi- time spent studying outside of class

viduals 1 standard deviation above and below the mean for TSA and ACT. would interact with motivation (see Table

4). Therefore, H4 was not supported.

January/February 2006 155

academic activities (TSA) and academ-

TABLE 4. Results of Moderated Multiple Regression Analysis of Time ic performance (see Table 4) also sup-

Spent Outside of Class on Academic Activities (TSA), Achievement

Striving (AST), and Semester Grade Point Average (SGPA) ports the above conclusion. However,

when we tested H3, the significant

main effect between TSA and academ-

Independent variable Slope SE t p R2 ic performance (Table 3) was not con-

sistent with the previous findings in H1

Control (Step 1) .10* and H4. That is, when ACT composite

Gender –0.23 0.13 –1.81 .07

Age –0.07 0.07 –1.08 .28 score was used as a predictor (in the

Race 0.87 0.28 4.42 .00* absence of achievement striving), TSA

Academic load 0.06 0.06 0.98 .33 had an impact on academic perfor-

Predictor (Step 2) .24* mance (see Table 3). Also, when

Achievement striving (AST) 0.40 0.07 6.36 .00* achievement striving was used as a pre-

Time studying (TSA) 0.01 0.06 0.18 .85

Moderator (Interaction) (Step 3) .24 dictor (in the absence of ACT compos-

AST × TSA 0.04 0.06 0.58 .57 ite), TSA did not impact academic per-

formance (see Table 4). In summary,

*p = .05. when ACT and TSA were used as pre-

dictors, TSA was able to explain varia-

tion in academic success that was not

DISCUSSION academic performance are more com- explained by ACT (Table 3). However,

plex than what individuals believe when achievement striving and TSA

We drew the following conclusions them to be. were used as predictors, TSA was

from the analyses. One important finding of this study unable to explain any variation in aca-

is the lack of evidence for a direct rela- demic performance that was not

1. Contrary to popular belief, the

tionship between TSW and academic explained by achievement striving.

findings suggest that TSW has no direct

performance (H2). TSW did not Results from H3 show that TSA was

influence on SGPA.

directly affect academic performance. a predictor and a moderator in the pres-

2. Based on the partial correlation,

At a time when the percentage of col- ence of ACT composite (a quasimoder-

findings suggest that TSA has no direct

lege students who work is at an all- ator). Results suggest the importance of

influence on academic performance

time high and administrators are con- both ability (i.e., ACT composite score)

(measured as SGPA).

cerned about its influence on academic and behavior (TSA) measures in deter-

3. The main effects of both ACT com-

performance, these results are encour- mining academic performance (H3). As

posite score and achievement striving

aging. Although more empirical evi- indicated by the significant and positive

are statistically significant.

dence may be required prior to making slope coefficient for the interaction term

4. In the presence of ACT composite

any definitive conclusions, these between ability and behavior (slope =

score, the main effect of TSA also has a

results did not contradict the findings 0.18), it is simply not ability alone that

statistically significant relationship with

of Strauss and Volkwein (2002) or brings about positive performance out-

SGPA. However, in the presence of

Light (2001). Contrary to popular comes. Variables such as TSA strength-

achievement striving, the main effect of

belief, both Strauss and Volkwein and en the influence that ability has on stu-

TSA does not have a significant interac-

Light found that working more hours dent performance. At a time when most

tion with SGPA.

was positively related to GPA and sug- efforts by administrators and instructors

5. The interaction between ACT com-

gested that students apply the same are focused on curriculum and pedagog-

posite score and TSA significantly

work ethic to both their academic and ical issues, this study’s results show the

influences SGPA.

paid work (i.e., those who earn higher need to also give attention to the com-

6. The interaction between TSA and

grades are students who are more position of today’s college student pop-

achievement striving did not significant-

motivated, and work harder and longer ulations in terms of what they bring to

ly influence SGPA.

than others). Perhaps academically class (i.e., study habits).

Based on partial correlation coeffi- strong students are better at balancing H4, which stated that the influence

cients, neither of the hypotheses that academic and job-related work, there- that behavior (i.e., TSA) has on aca-

tested direct relationships (H1 and H2) by reducing the negative effects that demic performance would be higher for

was supported. However, one of the TSW may have on academic perfor- students with high levels of motivation

hypotheses that investigated the mod- mance. than for students with low levels of

erator relationship was supported Based on the partial correlation (r = motivation, was not supported. In this

(H3). These results indicate that the .10, p > .05), the expected influence instance, it is clear that, in the absence

relationships that college students’ that TSA has on academic performance of ability as a predictor, high levels of

abilities (ACT composite score), moti- (H1) was not supported. When we test- motivation or behavior will not bring

vation (achievement striving), and ed H4, the insignificant main effect about the desired academic perfor-

behavior (TSA and TSW) have with between time spent outside of class on mance or outcome.

156 Journal of Education for Business

Implications uational (i.e., level of stress, courseload) Also, on the basis of the results from

variables, and, as such, the impact that H3, students with high ability who also

At a time when students spend less

TSW has on academic performance spend more time studying are the ones

time studying and more time working,

may be different for different student who are most likely to excel in college as

our results provide food for thought,

populations under different situations or indicated by their GPA (Figure 1). These

although it may be premature to derive

circumstances. We did not investigate are the type of students who are most

implications from the findings of this

those relationships in this study. likely to perform well academically and

study. Should subsequent researchers

bring universities as well as individual

using different samples validate find- Administration programs a high-quality academic repu-

ings of this study, there are implications

Study results also have implications tation, and, as such, a process should be

for both students and administrators.

for both the recruitment and retention of in place to recruit and retain them.

students. According to ACT, only 22% In addition to recruiting, retaining the

Students

of the 1.2 million high school graduates students and helping them to achieve

Results from studies such as this can who took the ACT assessment in 2004 their goals is an important issue for

be passed on to students. This can be achieved scores that would make them institutes of higher education. Research

easily done at a student orientation, in ready for college in all three academic results indicate that just over half of stu-

student newsletters, on the Web, or in areas: English, math, and science (ACT dents (63%) who began at a 4-year insti-

the classroom. It should be clearly com- News Release, 2004a). First, university tution with the goal of a bachelor’s

municated to them that their abilities, administrators as well as faculty should degree have completed that degree with-

motivation, and behavior work in tan- realize the importance of recruiting stu- in 6 years at either their initial institu-

dem to influence their academic perfor- dents who are academically prepared for tion or at another institution (U.S.

mance. If students are lacking in even college as indicated by ACT composite Department of Education, 2002).

one of these areas, their performances or SAT scores. Having the motivation or Unfortunately, an alarming number of

will be significantly lower. Once stu- a strong work ethic may not bring about schools have no specific plan or goals in

dents have a better understanding of desired performance outcomes in the place to improve student retention and

how ability, motivation, study time, and absence of ability, as evidenced by H4. degree completion (ACT News Release,

work patterns influence academic per- This can be a potential concern for col- 2004b). This shows the need for insti-

formance, they may be more likely to leges and universities that have low tutes of higher education to have their

understand their own situations and take admission standards (i.e., low ACT or own models to precisely predict and

corrective action. More important, they SAT score requirements and lower track the academic performance of their

may be less likely to have unreasonable acceptable high school GPAs) or open prospective students to ultimately mon-

expectations about their academic per- admission policies. Due to low admis- itor and control student retention and

formance and take more individual sion requirements, these institutions are dropout rates. Although measures of

responsibility for its outcome rather more likely to have a larger percentage ability such as ACT and SAT scores and

than conveniently putting the blame on of students who lack the minimum abil- high school GPA are widely used for

the instructor. For example, it is not ity needed to succeed in college com- college admission and GPA at college is

uncommon for intelligent students to pared with a smaller percentage of such used to evaluate the progress of the stu-

believe that ability will result in high students in colleges and universities that dent, the results of this study show that,

levels of academic performance regard- have high admission standards. There- if included, nonability variables such as

less of their level of motivation or effort. fore, colleges and universities that have motivation and TSA may significantly

The results of this study show the relatively low admission standards need improve these prediction models. This

impact of ability on academic perfor- to have a process in place to identify information, if collected and monitored,

mance to be much higher for students those students who lack the necessary would be useful in terms of decision

who spend more time studying than for abilities (e.g., quantitative skills, verbal making for university administrators as

those who spend less. skills) to succeed in college and provide well as faculty.

Also, the results did not show a direct them with ample opportunities to devel-

link between TSW and academic per- op those abilities while in college by Limitations and Direction for

formance. Although this can be an offering remedial courses. Failure to Future Research

encouraging finding at a time when a develop those abilities prior to taking

large percentage of college students are college-level courses can be a recipe for We made significant efforts to mini-

working longer hours while attending poor academic performance and low mize measurement error in variables

college (Curtis & Lucus, 2001), more retention rates. Data compiled by ACT that are normally self-reported, such as

research is needed prior to making gen- show a strong inverse relationship ACT composite scores and academic

eralizations. For example, it is plausible between admission selectivity and performance (GPA), as well as those

that the direct relationship between dropout rates: Highly selective = 8.7%, variables that rely on memory of past

TSW and academic performance can be selective = 18.6%, traditional = 27.7%, events, such as TSA and TSW (i.e., a

moderated by several personal (i.e., liberal = 35.5%, and open = 45.4% question such as time spent studying in

ability, motivation, study habits) and sit- (ACT Institutional Data File, 2003). a given week or time spent studying

January/February 2006 157

the previous week). By using universi- have contributed to the higher education Curtis, S., & Lucus, R. (2001). A coincidence of

needs? Employers and full-time students.

ty data for variables such as ACT com- literature. Employee Relations, 23(1), 38–54.

posite scores and academic perfor- Dreher, G. F., & Bretz, R. D. (1991). Cognitive

NOTE

mance as well as collecting the time ability and career attainment: Moderating

effects of early career success. Journal of

data based on a diary maintained by Correspondence concerning this article should be Applied Psychology, 76(3), 392–397.

participants during a 1-week period, addressed to Sarath A. Nonis, Professor of Market- Gose, B. (1998, January 16). More freshmen than

ing, Department of Management and Marketing,

we minimized measurement error. Box 59, Arkansas State University, State University,

ever appear disengaged from their studies, sur-

vey finds. The Chronicle of Higher Education,

Nevertheless, although results can be AR 72467. E-mail: snonis@astate.edu A37–A39.

generalized to the university where we Higher Education Research Institute. (2002). The

collected the data, additional evidence REFERENCES official press release for the American freshmen

2002. Los Angeles: University of California

will be required prior to generalizing Press.

Ackerman, D. S., & Gross, B. L. (2003, Summer).

statements to all university settings. In Is time pressure all bad? Measuring between Higher Education Research Institute. (2003). The

this respect, a national sample that free time availability and student performance official press release for the American freshmen

perceptions. Marketing Education Review, 12, 2002. Los Angeles: University of California

investigates these relationships can Press.

21–32.

either support or refute this study’s ACT Institutional Data File. (2003). National col- Legislative Analyst’s Office. (2001). Improving

findings. legiate dropout and graduation rates. Retrieved academic preparation for higher education.

January 9, 2005, from http://www.act.org/path/ Sacramento, CA: Author.

The study did not include a variable Light, R. J. (2001). Making the most of college.

postsec/droptables/index.html

that measured the effectiveness level or ACT News Release. (2004a). Crisis at the core: Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

quality of the time students spent Preparing all students for college and work. Macan, T. H. (1994). Time management: A

Retrieved January 9, 2005, from http://www process model. Journal of Applied Psychology,

studying, which may be one reason 79(3), 381–391.

.act.org/path/policy/index.html

why H1 was not supported. It is very ACT News Release. (2004b). U.S. colleges falling Macan, T. H., Shahani, C., Dipboye, R. L., &

likely that both the time that students short on helping students stay in school. Phillips, A. P. (1990). College students’ time

Retrieved January 9, 2005, from http://www management: Correlation with academic per-

spend studying as well as how this formance and stress. Journal of Educational

.act.org/news/release/2004/12-13-04.html

time is spent should be measured. That Bandura, A., & Schunk, D. H. (1981). Cultivating Psychology, 82(4), 760–768.

was certainly a limitation of this study. competence, self-efficacy, and intrinsic interest McFadden, K., & Dart, J. (1992). Time manage-

Results of future studies in which through proximal self-motivation. Journal of ment skills of undergraduate business students.

Personality and Social Psychology, 41(3), Journal of Education for Business, 68, 85–88.

researchers include this variable (i.e., 586–598. Mouw, J., & Khanna, R. (1993). Prediction of aca-

time management perceptions and Barling, J., & Charbonneau, D. (1992). Disentan- demic success: A review of the literature and

behaviors measured by Macan, 1994; gling the relationship between the achievement some recommendations. College Student Jour-

striving and impatience-irritability dimensions nal, 27(3), 328–336.

Macan, Shahani, Dipboye, & Phillips, of Type-A behavior, performance, and health. Multon, K. D., Brown, S. D., & Lent, R. W. (1991).

1990) will provide more insight into Journal of Organizational Behavior, 13, Relation of self-efficacy beliefs to academic out-

this issue. 360–378. comes: A meta-analytic investigation. Journal of

Barling, J., Kelloway, K., & Cheung, D. (1996). Counseling Psychology, 38(1), 30–38.

If TSA moderates the relationship Time management and achievement striving Nonis, S. A., & Wright, D. (2003). Moderating

between ACT composite and academic interact to predict car sales performance. Jour- effects of achievement striving and situational

performance, it is plausible for TSW nal of Applied Psychology, 81(6), 821–826. optimism on the relationship between ability

Barron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The mod- and performance outcomes of college students.

also to moderate the relationship erator-mediator variable distinction in social Research in Higher Education, 44(3), 327–346.

between ACT composite and academic psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory. New

performance. Therefore, in a future and statistical considerations. Journal of Per- York: McGraw-Hill.

sonality and Social Psychology, 51(6), Paden, N., & Stell, R. (1997, Summer). Reducing

study, researchers might investigate 1173–1182. procrastination through assignment and course

whether the relationship between ACT Carlson, D. S., Bozeman, D. P., Kacmar, M. K., design. Marketing Education Review, 7, 17–25.

composite score and academic perfor- Wright, P. M., & McMahan, G. C. (2000, Fall). Pascarella, E. T., & Terenzini, P. T. (1991). How

Training motivation in organizations: An analy- college affects students. San Francisco: Jossey-

mance is stronger for students who sis of individual-level antecedents. Journal of Bass.

spend less time working compared with Managerial Issues, 12, 271–287. Pinder, C. (1984). Work motivation. Glenview, IL:

the students who spend more time Chan, D., Schmitt, N., Sacco, J. M., & DeShon, R. Scott, Foresman.

P. (1998). Understanding pretest and posttest Smart, D. T., Kelley, C. A., & Conant, J. S. (1999).

working. We did not investigate these reactions to cognitive ability and personality Marketing education in the year 2000: Changes

relationships because they were outside tests. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83(3), observed and challenges anticipated. Journal of

the scope of this study. 471–485. Marketing Education, 21(3), 206–216.

Chatman, J. A. (1989). Improving interactional Smart, D. T., Tomkovick, C., Jones, E., &

We limited the personality variable organizational research: A model of person- Menon, A. (1999). Undergraduate marketing

under investigation to achievement organization fit. Academy of Management education in the 21st century: Views from

striving. Other variables such as opti- Review, 14(3), 333–349. three institutions. Marketing Education

Cleary, P. D., & Kessler, R. C. (1982). The esti- Review, 9(1), 1–10.

mism and self-efficacy are likely to mation and interpretation of modified effects. Spence, J. T., Helmreich, R. L., & Pred, R. S.

influence academic performance, and Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 23(2), (1987). Impatience versus achievement striv-

future studies will be able to address 159–169. ings in the Type-A pattern: Differential effects

Cohen, J., & Cohen, P. (1983). Applied multiple on student’s health and academic achievement.

these issues in more depth. However, in regression/correlation analysis for behavioral Journal of Applied Psychology, 72(4), 522–528.

this study, we addressed an important sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Statistical Abstract of the United States. (2002).

concern of the academic community at a Cubeta, J. F., Travers, N. L., & Sheckley, B. G. The national databook (pp. 168–169). Wash-

(2001). Predicting the academic success of ington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce and

time when such empirical research is adults from diverse populations. Journal of Statistics Administration.

not widely available, and, as a result, we College Student Retention, 2(4), 295–311. Strauss, L. C., & Volkwein, F. J. (2002). Compar-

158 Journal of Education for Business

ing student performance and growth in 2- and Wise, S. L., Peters, L. H., & O’Conner, E. J. predictability of social behavior. Journal of

4-year institutions. Research in Higher Educa- (1984). Identifying moderator variables using Personality and Social Psychology, 53(6),

tion, 43(2), 133–161. multiple regression: A reply to Darrow and 1159–1177.

U.S. Department of Education. (2002). Descrip- Kahl. Journal of Management, 10(2), Zimmerman, B. J. (1989). A social-cognitive

tive summary of 1995–1996 beginning postsec- 227–236. view of self-regulated academic learning.

ondary students: Six years later. Washington, Wright, J., & Mischel, W. (1987). A conditional Journal of Educational Psychology, 81(3),

DC: Author. approach to dispositional constructs: The local 329–339.

January/February 2006 159

View publication stats

You might also like

- Defining Dynamics SymbolsDocument3 pagesDefining Dynamics SymbolsMelissa AguilarNo ratings yet

- DIY Piñata PDFDocument12 pagesDIY Piñata PDFMelissa AguilarNo ratings yet

- Foreign Language DepartmentDocument1 pageForeign Language DepartmentMelissa AguilarNo ratings yet

- Conversation Analysis and Second Languag PDFDocument4 pagesConversation Analysis and Second Languag PDFMelissa AguilarNo ratings yet

- Defining Dynamics SymbolsDocument3 pagesDefining Dynamics SymbolsMelissa AguilarNo ratings yet

- Quasi-Experimental Research QuestionnaireDocument3 pagesQuasi-Experimental Research QuestionnaireMelissa AguilarNo ratings yet

- Edusemiotics Pedagogy of Concepts PedagoDocument1 pageEdusemiotics Pedagogy of Concepts PedagoMelissa AguilarNo ratings yet

- I Love You LordDocument1 pageI Love You LordShadrach GrentzNo ratings yet

- Edusemiotics Pedagogy of Concepts PedagoDocument1 pageEdusemiotics Pedagogy of Concepts PedagoMelissa AguilarNo ratings yet

- August Lesson # 3 3rdDocument2 pagesAugust Lesson # 3 3rdMelissa AguilarNo ratings yet

- Memory Game Guide - Animals, Habitats, SkillsDocument1 pageMemory Game Guide - Animals, Habitats, SkillsMelissa AguilarNo ratings yet

- Info de Inglés.Document2 pagesInfo de Inglés.Melissa AguilarNo ratings yet

- 16 Parts Catalog MilerDocument124 pages16 Parts Catalog MilerkaduwdNo ratings yet

- Melissa Aguilar. Poems' Analyses Assignment.Document12 pagesMelissa Aguilar. Poems' Analyses Assignment.Melissa AguilarNo ratings yet

- Music TheoryDocument277 pagesMusic TheoryPhilip Mingin100% (5)

- Pronoun12 Demonstrative PronounsDocument2 pagesPronoun12 Demonstrative PronounsjuszMyNo ratings yet

- 12th Night - Education Program PDFDocument11 pages12th Night - Education Program PDFMelissa AguilarNo ratings yet

- TEACHERS' NAMES: Rosario Guadalupe Zepeda, Silvia Melissa Aguilar Fernández. LEVEL: INTERMEDIATE 1 MODULE: 1 TEXTBOOKDocument3 pagesTEACHERS' NAMES: Rosario Guadalupe Zepeda, Silvia Melissa Aguilar Fernández. LEVEL: INTERMEDIATE 1 MODULE: 1 TEXTBOOKMelissa AguilarNo ratings yet

- Conversación 3. Revisado.Document3 pagesConversación 3. Revisado.Melissa AguilarNo ratings yet

- Your Song Partitura PDFDocument4 pagesYour Song Partitura PDFMelissa AguilarNo ratings yet

- Peer Assessment Rubric - Composition IIDocument1 pagePeer Assessment Rubric - Composition IIMelissa AguilarNo ratings yet

- TEACHERS' NAMES: Rosario Guadalupe Zepeda, Silvia Melissa Aguilar Fernández. LEVEL: INTERMEDIATE 1 MODULE: 1 TEXTBOOKDocument3 pagesTEACHERS' NAMES: Rosario Guadalupe Zepeda, Silvia Melissa Aguilar Fernández. LEVEL: INTERMEDIATE 1 MODULE: 1 TEXTBOOKMelissa AguilarNo ratings yet

- IMSLP47807-PMLP03123-01 - Mozart Violin-Konzert Nr. 3 G Dur K.V.216 Full ScoreDocument37 pagesIMSLP47807-PMLP03123-01 - Mozart Violin-Konzert Nr. 3 G Dur K.V.216 Full ScoreMelissa AguilarNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Republic of the Philippines Department of Education Weekly Home Learning Plan for Grade 12 Cookery NC II Week 4Document4 pagesRepublic of the Philippines Department of Education Weekly Home Learning Plan for Grade 12 Cookery NC II Week 4Mary Grace ClaroNo ratings yet

- Data MiningDocument1 pageData MiningdanungsbNo ratings yet

- Synopsis of ACC LTDDocument5 pagesSynopsis of ACC LTDakki_6551No ratings yet

- RICARDO G. SIGU Sec6Document5 pagesRICARDO G. SIGU Sec6Donna Rose Sanchez FegiNo ratings yet

- Study Habits of Grade 11 and 12 Abm Students in Taal Senior High SchoolDocument26 pagesStudy Habits of Grade 11 and 12 Abm Students in Taal Senior High SchoolAphol Joyce Mortel67% (3)

- Funding Guidelines English LIT Call 10 2021Document6 pagesFunding Guidelines English LIT Call 10 2021Fitriaty FaridaNo ratings yet

- Riddhi Vadodaria Research PaperDocument24 pagesRiddhi Vadodaria Research PaperRVNo ratings yet

- Example of Thesis Paper PDFDocument2 pagesExample of Thesis Paper PDFNick0% (1)

- Pedagogical Renewal in A Postcolonial Context 2nd RevisionDocument29 pagesPedagogical Renewal in A Postcolonial Context 2nd RevisionAna TomicicNo ratings yet

- Parts of The Research Report and Oral Presentation GuidelinesDocument4 pagesParts of The Research Report and Oral Presentation GuidelinesSheilaBaquiranNo ratings yet

- Theses 2005 Ha ThesisDocument56 pagesTheses 2005 Ha ThesisFranco Riva ZafersonNo ratings yet

- Role of Behavioral Measures in Accounting for Human ResourcesDocument11 pagesRole of Behavioral Measures in Accounting for Human ResourcesYukaFaradilaNo ratings yet

- E Recruitment Process and Organizational Performance A Literature ReviewDocument10 pagesE Recruitment Process and Organizational Performance A Literature ReviewEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Sip Kimr 2020-22Document10 pagesSip Kimr 2020-22Kirti WajgeNo ratings yet

- Methods of Categorization and Classification of ProverbsDocument5 pagesMethods of Categorization and Classification of ProverbsCentral Asian StudiesNo ratings yet

- Iii Summative Test 12Document6 pagesIii Summative Test 12Kiella SultanNo ratings yet

- What Is Statistical SignificanceDocument4 pagesWhat Is Statistical SignificanceJuwerio Mohamed Omar MohamedNo ratings yet

- Para3tryme PDFDocument5 pagesPara3tryme PDFRaiza T. MatindoNo ratings yet

- Remembering The Aztecs AssignmentDocument3 pagesRemembering The Aztecs Assignmentapi-313436217No ratings yet

- Online Learning NewsletterDocument164 pagesOnline Learning Newslettertino3528No ratings yet

- The Anatomy of Prototypes: Prototypes As Filters, Prototypes As Manifestations of Design IdeasDocument27 pagesThe Anatomy of Prototypes: Prototypes As Filters, Prototypes As Manifestations of Design IdeasAaron AppletonNo ratings yet

- Your Guide To: Advancing Your Career in BiotechnologyDocument29 pagesYour Guide To: Advancing Your Career in BiotechnologyRanjith KumarNo ratings yet

- Kinetic Architecture DissertationDocument11 pagesKinetic Architecture DissertationinayathNo ratings yet

- Hurk Van Den Master ThesisDocument70 pagesHurk Van Den Master ThesisNayab AkhtarNo ratings yet

- Parts of A Research ProposalDocument1 pageParts of A Research ProposalRoan Eam TanNo ratings yet

- Minor Project Event ManagementDocument37 pagesMinor Project Event ManagementShruti SharmaNo ratings yet

- بحثDocument79 pagesبحثsojoud shorbajiNo ratings yet

- Risk Management Prtactices of Sport CoachesDocument34 pagesRisk Management Prtactices of Sport CoachesJasmin Goot RayosNo ratings yet

- Subculture of Consumption: New Bikers and Their Harley PassionDocument20 pagesSubculture of Consumption: New Bikers and Their Harley PassionValeed ChNo ratings yet

- The Problem and Its BackgroundDocument33 pagesThe Problem and Its BackgroundJamilleNo ratings yet