Professional Documents

Culture Documents

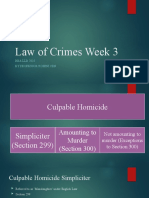

Criminal Law

Uploaded by

Debasish NathOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Criminal Law

Uploaded by

Debasish NathCopyright:

Available Formats

www.gupshupstudy.

com CRIMINAL LAW

Is Also Covered in the Corresponding Clause of Section 300 But Does not Fall in Any

of the Exceptions to Section 300

Clause 4, "Person committing the act knows that it is so imminently dangerous that it must, in

all probability, cause death or such bodily injury as is likely to cause death.... without any

excuse for incurring the risk of causing death. "

The 4th clause contemplates the doing of an imminently dangerous act in general, and not the

doing of any bodily harm to any particular individual [as per illustration (d) of Section 300],

This clause cannot be applied until it is clear that clauses 1,2 and 3 of the section each and all

of them fail to suit the circumstances. Intention is not an essential ingredient of this clause

Section 300(4) is usually applied to cases where the act of the offender is not directed against

any particular person. There may even be no intention to cause harm or injury to any

particular individual. What this clause contemplates is the imminently dangerous act which in

all probabilities is done, without any intention to kill a particular person but with the

knowledge that death is very likely and that such act is done without any excuse.

The Supreme Court in Ram Prasad Verses State, had held that this clause is usually invoked in

cases where there is no intention to cause death of any particular individual. The clause is

applied in cases where there is such callousness towards the result, and the risk taken that it

may be stated that the person knows that the act is likely to cause death or such bodily injury

as is likely to cause death. The explosion of a bomb in a crowded room must have been

known to the accused that it would cause death, the fact that the accused had no intention of

killing a particular person does not take the case outside the purview of clause (4).

In Gorachand Gopee case, the court has pointed out that clause fourthly is designed for that

class of cases where the act of the accused is not directed against any one in particular but

there is that recklessenss or negligence, which places the lives of many in jeopardy, of which

the accused is well aware. For example, causing death by firing a loaded gun into a crowd or

by poisoning a well from which people are accustomed to draw water.

An act done with the knowledge of its consequences is not prima facie murder. It becomes

murder only if it can be positively affirmed that there was no excuse. When a risk is incurred

—even a risk of the gravest possible character which must normally result in death—the

taking of that risk, is not murder, unless it was inexcusable to take it [Emperor Verses

Dhirajia]

Page 2 of 33 www. gup shup study. com

www.gupshupstudy.com CRIMINAL LAW

The main ingredient of this clause is that the person committing the act in question should

have had the knowledge that the act done is so imminently dangerous that it must in all

probability cause the death or such bodily injury as is likely to cause death and the act was

committed without any excuse for causing death or such bodily injury as is likely to cause

death (Sonnu Muduli Verses Emperor).

Hence, this clause deals with cases where an act which is dangerous is done, without any

intention to kill a particular person, but with knowledge that death is very likely and that such

act is done without any excuse. A threat caused by incarnations or a belief in witchcraft does

not justify the causing of death. So also, 'divine influence or inspiration' cannot be pleaded in

defence to a charge of an offence [Munniswami Verses Emperor]

In Bharat, the accused offered a child to a crocodile under a superstitious but bona fide belief

that the child would be returned unharmed but the child was killed. He was held guilty of

murder under clause fourthly of Section 300.

Section 302. Punishment for Murder, "Whoever commits murder shall be punished with death

or imprisonment for life, and shall also be liable to fine."

Therefore, Section 302 provides two alternative punishments for murder, viz., death sentence

or imprisonment for life. It is important to note here that death penalty should be imposed in

gravest cases of extreme culpability by taking into consideration the circumstances of the

offenders and crime. Death sentence must be imposed when life imprisonment is inadequate

punishment, after striking balance between the aggravating and the mitigating circumstances

(Bachan Singh Verses State of Punjab).

Page 3 of 33 www. gup shup study. com

www.gupshupstudy.com CRIMINAL LAW

Page 4 of 33 www. gup shup study. com

www.gupshupstudy.com CRIMINAL LAW

Motive Verses intention

The distinction between Sections 299 and 300 was made clear by Melvill J. in R. Verses

Govinda and by Sarkaria J. in R. Verses Punnaya It must be remembered that as per

Article 141 of the Constitution of India, the law declared by the Supreme Court is the law of

the land and binding on everyone. In this case the accused had knocked his wife down, put

one knee on her chest, and struck her two or three violent blows on the face with the closed

fist, producing extravansion of blood on the brain and she died in consequence, either on the

spot, or very shortly afterwards, there being no intention to cause death and the bodily injury

not being sufficient in the ordinary course of nature to cause death. The accused was liable for

culpable homicide not amounting to murder.

For the purpose of comparison and bringing out the distinction clearly, Section 299 and

Section 300 may be put as follows,

Section 299 Section 300

A person commits culpable homicide Except in the cases if the act by which the death is

caused if is done... hereinafter excepted is done. Culpable homicide is murder if the act by

which death is caused is done...

INTENTION

(a) With the intention of causing death, [as per Illustration (a) to Section 299]

(b) With the intention of causing such bodily injury as is likely to cause death, [as per

Illustration (b) to Section 299]

(1) With the intention of causing death, [as per Illustration (a) to Section 300]

(2) With the intention of causing such bodily injury as the offender knows to be likely to

cause the death of the person to whom the harm is caused, [as per Illustration (b) to Section

300],

KNOWLEDGE

(c) With the knowledge that he is (3) With the intention of causing likely by such act to

cause death, bodily injury to any person, and [as per Illustration (c) to Section the bodily

injury intended to be 299] inflicted is sufficient in the

ordinary course of nature to cause death, [as per Illustration (c) to Section 300]

(4) With the knowledge that the act is so imminently dangerous that it must in all probability

cause death, or such bodily injury as is likely to cause death, [as per Illustration (d) to Section

300]

Page 5 of 33 www. gup shup study. com

www.gupshupstudy.com CRIMINAL LAW

The first clause of Section 300 reproduces the first part of Section 299, therefore ordinarily if

the case comes within Clause (a) of Section 299, it would ar lount to murder [Jaya Raj Verses

State of T.N.],

Clause (b) of Section 299 corresponds with Clauses (2) and (3) of Section 300. Clause (b) of

Section 299 does not postulate any such knowledge on the part of the offender. Thus, if the

assailant had no knowledge about the disease of the victim, nor an intention to cause death or

bodily injury sufficient in the ordinary course of nature to cause death, the offence will not be

murder, even if the injury which caused the death, was intentionally given.

A comparison of clause (b) of Section 299 with Clause (3) of Section 300 would show that the

offence is culpable homicide if the bodily injury intended to be inflicted is likely to cause

death, it is murder if such injury is sufficient in the ordinary course of nature to cause death.

The distinction is fine but appreciable. Ref The decision of most of the doubtful cases depends

on a comparison of these two clauses. The word "likely" means "probably." When the chances

of a thing happening are greater than its not happening, we say the thing will "probably"

happen. When the chances of its happening are very high, we say that it will 'most probably'

happen. An injury sufficient in the ordinary course of nature to cause death only means that

"death will be the most probable result of the injury having regard to the ordinary course of

nature". The expression does not mean that death must result. Thus the distinction between

clause (b) of section 299 and clause (3) of section 300 would depend very much upon the

degree of probability or likelihood of death in consequence of the injury.

Clause (c) of Section 299 and Clause (4) of Section 300 appear to apply to cases in which

there is no intention to cause death or bodily injury but knowledge that the act is dangerous

and therefore likely to cause death. Both clauses require knowledge of the probability of the

act causing death. Clause (4) requires knowledge in a very high degree of probability.

The following factores are necessary,

(1) That the act is imminently dangerous,

(2) That in all probability it will cause death or such bodily injury as is likely to cause death,

and

(3) That the act is done without any excuse for incurring the risk.

Whether the offence is culpable homicide or murder, depends upon the degree of risk to

human life. If death is a likely result, it is culpable homicide, if it is the most probable result, it

is murder. Furious driving and firing at a mark near a public road are cases of these

Page 6 of 33 www. gup shup study. com

www.gupshupstudy.com CRIMINAL LAW

description.

Page 7 of 33 www. gup shup study. com

www.gupshupstudy.com CRIMINAL LAW

Page 8 of 33 www. gup shup study. com

www.gupshupstudy.com CRIMINAL LAW

Distinction between culpable homicide & murder

QUESTION 1. What do you understand by culpable homicide and what elements are

necessary to constitute this offence? Discuss giving illustrations. When does culpable

homicide amount to murder?

Answer. Homicide, Homicide is the killing of a human being by a human being and culpable

means criminal. Homicide may be lawful or unlawful. It is lawful where death is caused by

accident without any criminal intention, or caused in the exercise of the right of private

defence of person or property or by a person of unsound mind. Unlawful homicide includes

culpable homicide not amounting to murder.

Culpable Homicide, Section 299 lays down that whoever causes death by doing an act with

the intention of causing death, or with the intention of causing such bodily injury as is likely to

cause death, or with the knowledge that he is likely by such act to cause death, commits the

offence of culpable homicide.

Essential Elements, Its essential elements consist of the following, viz., the causing of death

by doing

(1) an act with the 'intention of causing death,

(2) an act with the intention of causing such bodily injury as is likely to cause death, or (in) an

act with the knowledge that it was likely to cause death.

A few illustrations will bring out the principles clearly,

(a) A lays sticks and turf over a pit, with the intention of thereby causing death, or with the

knowledge that death is likely to be caused thereby. Z believing the ground to be firm treads

on it, falls in and is killed. A has committed the offence of culpable homicide,

(b) A knows Z to be behind a bush. B does not know it. A intending to cause or knowing it to

be likely to cause Z's death, induces B to fire at the bush. B fires and kills Z. Here B may be

guilty of no offence, but A has committed the offence of culpable homicide,

(c) A, by shooting at a fowl with intent to kill and steal it, kills B, who is behind a bush, A not

knowing that he was there. Here, although A was doing an unlawful act, he was not guilty of

culpable homicide, as he did not intend to kill B or cause death by doing an act that he knew

was likely to cause death.

The three Explanations to the Section provide,

(1) A person who causes bodily injury to another who is labouring under a disorder, disease

or bodily infirmity, and thereby accelerates the death of that other, shall be deemed to have

caused his death.

(2) Where death is caused by bodily injury, the person who causes such bodily injury shall be

deemed to have caused the death, although by resorting to proper remedies and skilful

Page 9 of 33 www. gup shup study. com

www.gupshupstudy.com CRIMINAL LAW

treatment the death might have been pre-vented. The deceased was stabbed in the abdomen

by a knife and he died of gangrene and paralysis of intestines. It was held that the fact that if

an operation had taken place within an hour of the infliction of the abdominal injury the life of

the deceased might have been saved, could not, in view of this Explanation, remove the

offence from the ambit of culpable homicide.

(3) The causing of the death of a child, in the mother's womb is not homicide. But it may

amount to culpable homicide to cause the death of a living child if any part of that child has

been brought forth, though the child may not have breathed or been completely born.

Murder, Section 300, I.PC. lays down that culpable homicide is murder, if the act by which

the death is caused is done with the intention of causing death, or secondly, if it is done with

the intention of causing such bodily injury as the offender knows to be likely to cause the

death of the person to whom the harm is caused, or thirdly, if it is done with the intention of

causing bodily injury to any person and the bodily injury intended to be inflicted is sufficient in

the ordi-nary course of nature to cause death, or fourthly, if the person com-mitting the act

knows that it is so imminently dangerous that it must, in all probability, cause death or such

bodily injury as is likely too cause death, and commits such act without any excuse for

incurring the risk of causing death or such injury as aforesaid. Illustrations,

(1) A shoots Z with the intention of killing him. Z dies in consequence. A commits murder,

(2) A knowing that Z, is labouring under such a disease that a blow is likely to cause his

death, strikes him with the intention of causing bodily injury. Z dies in consequence of the

blow. A is guilty of murder, although the blow might not have been sufficient in the ordinary

course of nature to cause the death of a person in a sound state of health. But it is not murder

if B had not known that Z was labouring under any disease,

(3) A intentionally gives Z a swords-cut sufficient to cause the death of a man in the ordinary

course of nature. Z dies in consequence. Here A is guilty of murder, although he may not

have intended to cause Z's death,

(4) A, without any excuse, fires a loaded cannon into a crowd of persons and kills one of

them. A is guilty of murder, although he may not have had premeditated design to kill any

particular individ-ual.

The Supreme Court in Virsa Singh Verses State of Punjab, has laid down that the prosecution

must prove the following facts before it can bring a case under Section 300 "thirdly",— Firstly,

it must establish, quite objectively, that a bodily injury is present,

Secondly, the nature of the injury must be proved, these are purely objective investigations,

Thirdly, it must be proved that there was an intention to inflict that particular bodily injury, that

is to say that it was not accidental or unintentional or that some other kind of injury was

Page 10 of 33 www. gup shup study. com

www.gupshupstudy.com CRIMINAL LAW

intended.

Fourthly, it must be proved that injury of the type just described made up of the three

elements set out above is sufficient to cause death in the ordinary course of nature. This part

of the enquiry is purely objective and inferential and has nothing to do with the intention of the

offender. Bose J. further observed, "Once these four elements are established by the

prosecution (and of course, the burden is on the prosecution throughout) the offence is

murder under Section 300 'thirdly'. It does not matter that there was no intention to cause

death. It does not matter that there was to intention even to cause an injury of a kind that is

sufficient to cause death in the ordinary course of nature (not that there is any real distinction

between the two). It does not even matter that there is no knowledge that an act of that kind

will be likely to cause death. Once the intention to cause the bodily injury actually found to be

present is proved, the rest of the enquiry is purely objective and the only question is whether,

as a matter of purely objective inference, the injury is sufficient in the ordinary course of

nature to cause death."

In Laxman Kalu Nikalji Verses The State of Maharashtra. Where a single injury was inflicted

on the deceased with a knife 2 inch below the outer 1/3 of right clavicle on the right side of

the chest and penetrated to the depth of 4 inch into the chest cavity. Dealing with the question

whether the offence would be covered by 'thirdly' of Section 300 of the Indian Penal Code.

Hidayatullah, C.J. observed, "That section requires that the bodily injury must be intended

and the bodily injury intended to be caused must be sufficient in the ordinary course of nature

to cause death. This clause is in two parts, the first is a subjective one which indicates that

the injury must be an intentional one and not an accidental one, the second part is objective

in that looking at the injury intended to be caused, the court must be satisfied that it was

sufficient in the ordinary course of nature to cause death." On the basis of the evidence it was

held in the aforesaid case that the first part was complied with and the second part was not

fulfilled because but for the fact that the injury caused the severing of artery, death might not

have ensued and the injury which the accused in-tended to cause did not include specifically

the cutting of the artery but to wound the victim in the neighbourhood of the clavicle. In these

circumstances. Section 300 'thirdly' was held to be inapplicable. Having regard to the fact that

the appellant had used a dangerous weapon like a rifle (being a police constable he must

have known that it was a dangerous weapon) and having regard to the fact that he had fired

at Kaptan Singh as many as five shots, one of which was fired after Kaptan Singh was hit by

a bullet and collapsed on the ground it was impossible to accept the contention that the

appellant had not done the act with the intention of causing his death. It was naive to argue

that the intention was merely to frighten him or to cause grievous hurt for it overlooked the

two salient features, viz., (a) as many as five shots were fired from his 303 rifle and (b) that

Page 11 of 33 www. gup shup study. com

www.gupshupstudy.com CRIMINAL LAW

he fired a shot even after Kaptan Singh had collapsed on the ground having been hit by one

of the shots. A bare glance at Section 300 of the Indian Penal Code would show that if the act

is done with the intention of causing death, culpable homicide would be murder. Under clause

secondly of Section 300 if the act is done with the intention of causing such bodily injury as

the offender knows to be likely to cause the death of he person to whom the harm is caused it

would amount to murder. When the appellant, a police constable fired from his 303 rifle (he

must have known that it was a deadly weapon) no other inference is possible but that he

intended to cause such bodily injury as he knew to be likely to cause death of the person to

whom the harm was caused. Clause thirdly of Section 300 provides that if the act is done with

the intention of causing bodily injury to any person and the bodily injury intended to be

inflicted is sufficient in the ordinary course of nature to cause death it would amount to

murder. Again having regard to the facts narrated hereinabove no other conclusion was

possible except that the appel-lant intended to inflict such bodily injuries to the deceased

which were sufficient in the ordinary course of nature to cause death. In any view of the

matter it would fall under clause 4thly, which provided that if the person committing the act

knows that it is so imminently dangerous that it must, in all probability, cause death or such

bodily injury as is likely to cause death, and commits such act without any excuse for

incurring the risk of causing death or such injury as afore-said it would amount to murder.

Illustrations, (a), (c) and (d) of Section 300, I.P.C. reading as under may be flashed on the

mental screen in order to reinforce this conclu-sion,—

"(a) A shoots Z with the intention of killing him. Z dies in conse-quence. A

commits murder, (b) A intentionally gives Z a sword-cut or club-wound sufficient to cause

the

death of a man in the ordinary course of nature. Z dies in consequence.

Here A is guilty of murder, although he may not have intended to causeA without any excuse

fires a loaded cannon into a crowd of persons and kills one of them. A is guilty of murder,

although he may not have had a premeditated design to kill any particular individual."

QUESTION2. Discuss the broad guidelines as to when an offence is murder and when it is

culpable homicide not amounting to murder.

Answer. The academic distinction between 'murder' and 'culpable homicide not amounting to

murder' has vexed the courts for more than a century. The confusion is caused if courts losing

sight of the true scope and meaning of the terms used by the legislature in these sections

allow themselves to be drawn into minute abstractions. The safest way of approach to the

interpretation and application of those provisions seems to be to keep in focus the key words

used in the various clauses of Sections 299 and 300.

Page 12 of 33 www. gup shup study. com

www.gupshupstudy.com CRIMINAL LAW

Clause (b) of Section 299 corresponds with clauses (2) and (3) of Section 300. The

distinguished feature of the mens rea requisite under clause (2) is the knowledge possessed

by the offender regarding the particular victim being in such a peculiar condition or state of

health that the intentional harm caused to him is likely to be fatal, notwith-standing the fact

such harm would not in the ordinary way of nature be sufficient to cause death of a person in

normal health or condition. It is noteworthy that the 'intention to cause death' is not an

essential requirement of clause (2). Only the intention of causing the bodily injury coupled

with the offender's knowledge of the likelihood of such injury causing the death of the

particular victim is sufficient to bring the killing within the ambit of this clause. This aspect of

clause (2) is borne out by illustration (b) appended to Section 300.

Clause (b) of Section 299 does not postulate any such knowledge on the part of the offender.

Instance of causes falling under clause (2) of Section 300 can be where the assailant causes

death by giving a fist blow intentionally knowing that the victim is suffering from an enlarged

liver or enlarged spleen or diseased heart and such blow is likely to cause death of that

particular person as a result of the rupture of the liver or spleen or the failure of the heart, as

the case may be. If the assailant had no such knowledge about the disease or special fraility

of the victim nor an intention to cause death or bodily injury sufficient in the ordinary course of

nature to cause death, the offence will not be murder, even if the injury which caused the

death, was intentionally given. In clause (3) of Section 300, instead of the words 'likely to

cause death' occurring in the corresponding clause (b) of Section 299, the words 'sufficient in

the ordinary course of nature' have been used. Obviously, the distinction lies between a

bodily injury likely to cause death and a bodily injury sufficient in the ordinary course of nature

to cause death. The distinction is fine but real, and, if overlooked, may result in miscarriage of

justice. The difference between clause (b) of Section 299 and clause

(3) of Section 300 is one of the degree of probability of death resulting from the intended

bodily injury. To put it more broadly, it is the degree of probability of death which determines

whether a culpable homicide is of the gravest, medium or the lowest degree. The word likely'

in clause (b) of Section 299 conveys the sense of 'probable' so distinguished from a mere

possibility. The words 'bodily injury...sufficient in the ordinary course of nature to cause death'

mean that death will be the 'most probable' result of the injury, having regard to the ordinary

course of nature. For cases to fall within clause (3), it is not necessary that the offender

intended to cause death, so long as the death ensues from the intentional bodily injury or

injuries sufficient to cause death in the ordinary course of nature.

Even if the intention of the accused was limited to the infliction of a bodily injury sufficient to

cause death in the ordinary course of nature and did not extend to the intention of causing

death the offence would be murder. Illustration (c) appended to Section 300 clearly brings out

Page 13 of 33 www. gup shup study. com

www.gupshupstudy.com CRIMINAL LAW

this point Clause (c) of Section 299 and clause (4) of Section 300 both require knowledge of

the probability of the act causing death. Clause (4) of Section 300 would be applicable where

the knowledge of the offender as to the probability of death of a person or persons in general

—as distinguished from a particular person or persons—being caused from his imminently

dangerous act, approximates to a practical certainty. Such knowledge on the part of the

offender must be of the highest degree of probability, the act having been committed by the

offender without any excuse for incurring the risk of causing death or such injury as aforesaid.

From the above conspectus, it emerges that whenever a court is confronted with the question

whether the offence is 'murder' or 'culpable homicide not amounting to murder' on the facts of

case,, it will be convenient for it to approach the problem in three stages. The question to be

considered at the first stage would be, whether the accused has done an act by doing which

he has caused the death of another. Proof of such causal connection between the act of the

ac-cused and the death, leads the second stage for considering whether that act of the

accused amounts to "culpable homicide" as defined in Section 299. If the answer to this

question is prima facie found in the affirmative, the stage for considering operation of Section

300, Indian Penal Code, is reached. This is the stage at which the Court should determine

whether the facts proved by the prosecution bring the case within the ambit of any of the four

clauses of the definition of 'mur-der' contained in Section 300. If the answer to this question is

in the negative the offence would be 'culpable homicide not amounting to murder', punishable

under the first or the second part of Section, 304, depending respectively on whether the

second or the third clause of Section 299 is applicable. If this question is found in the positive,

but the case comes within any of the Exceptions enumerated in Section 300, the offence

would still be 'culpable homicide not amounting to murder', punishable under the first part of

Section 304, Penal Code.

The above are only broad guidelines and not cast-iron imperatives. In most cases, these

observance will facilitate the task of Court. But sometimes the facts are so intertwined and the

second and the third stages so telescoped into each other, that it may not be convenient to

give a separate treatment to the matters involved in the second and third stages.

General

QUESTION 1. When does culpable homicide not amount to murder? Or describe briefly

giving illustrations the circumstances under which culpable homicide does not amount to

murder on account of the provocation given to the accused.

Answer. The following Exceptions to Section 300 provide for cases where culpable homicide

is not murder,—

Exception. 1, Culpable homicide is not murder if the offender, whilst deprived of the power of

Page 14 of 33 www. gup shup study. com

www.gupshupstudy.com CRIMINAL LAW

self-control by grave and sudden provocation, causes the death of person who gave the

provocation or causes the death of any other person by mistake or accident. The above

exception is subject to the following proviso, Firstly, That the provocation is not sought or

voluntarily pro-voked by the offender as an excuse for killing or doing harm to>any person.

Secondly, That the provocation is not given by anything done in obedience to the law, or by a

public servant in the lawful exercise of the powers of such public servant. Thirdly, That the

provocation is not given by anything done in the lawful exercise of the right of private

defence.

Explanation, Whether the provocation was grave and sudden enough to prevent the offence

from amounting to murder, is a question of fact. The above exception provides that the act

must be done whilst the person doing it is deprived of self control by grave and sudden

provocation, that is, it must be done under the immediate impulse of provocation. The

provocation must be grave and sudden and of such a nature as to deprive the accused of the

power of sett-control. Mere verbal provocation, however, even if it be by threats or gestures or

by the use of abusive and insulting language, cannot induce a reasonable man to commit an

act of violence of be regarded as a great provoca-tion within the meaning of Exception 1 to

Section 300. The test of grave and sudden provocation is whether provocation given was in

the circumstances of the case likely to cause a normal reasonable man to loose control of

himself to the extent - of inflicting the injury or injuries that he did inflict. „ Illustrations,

(a) It has been held that a confession of adultery by a wife to her husband, who in

consequence kills her, is such a grave and sudden

-provocation as will entitle the court to hold it to be culpable homicide instead of murder, but a

similar confession of illicit intercourse by a woman who was not the accused's wife but only

engaged to be married to him cannot, if he kills her in consequence, justify such a view,

(b) A, under the influence of passion excited by a provocation given by Z. intentionally kills Y,

Z's child. This is murder, inasmuch as the provocation was not given by the child, and the

death of the child was not caused by accident or misfortune in doing an act caused by the

provocation,

(c) Y gives grave and sudden provocation to A. A, on this provocation, fires a pistol at Y

neither intending nor knowing himself to be likely to kill Z, who is near him, but out of sight A

kills Z. Here A has not committed murder, but merely culpable homicide,

(d) A is lawfully arrested by Z, a bailiff. A is excited to sudden and violent passion by the

arrest, and kills Z. This is murder, inasmuch as the provocation was given by a thing done by

a public servant in the exercise of his powers,

(e) A appears as a witness before Z, a Magistrate. Z, says that he does not believe a word of

A's deposition, and that A has perjured himself. A is moved to sudden passion by these

Page 15 of 33 www. gup shup study. com

www.gupshupstudy.com CRIMINAL LAW

words, and kills Z. This is murder,

(f) A attempts to pull Z's nose. Z, in the exercise of the right of private defence, lays hold of A

to prevent him from doing so. A is moved to sudden and violent passion in consequence, and

kills Z. This is murder, inasmuch as the provocation was given by a thing done in the exercise

of the right of private defence,

(g) Z strikes B. B is by this provocation excited to violent rage. A, a bystander intending to

take advantage of B's rage, and to cause him to kill Z, puts a knife into B's hand for that

purpose. B kills Z with the knife. Here B may have committed only culpable homicide, but A is

guilty of murder.

Exception 2, Culpable homicide is not murder if the offender, in the exercise in good faith of

the right of private defence of person or property, exceeds the power given to him by law and

causes the death of the

person against whom he is exercising such right of defence without premeditation, and

without any intention of doing more harm than is necessary for the purpose of such defence.

Illustration, Z attempts to horsewhip A, not in such a manner as to cause grievous hurt to A. A

draws out a pistol. Z persists in the assault. A, believing in good faith that he can by no other

means prevent himself, from being horsewhipped, shoots Z dead, A has not committed

murder, but only culpatfle homicide.

This exception only applies when the right of private defence is 'exceeded without any

intention of doing more harm than is necessary.

Exception 3, Culpable homicide is not murder if the offender being a public servant or aiding

a public servant acting for the advancement of public justice, expeeds the powers given to

him by law, and causes death ' by doing an act which he, in good faith, believes to be lawful

and necessary for the due (discharge of his duty as such public servant and without ill-will

towards the person whose death is caused.

Explanation 4, Culpable homicide is not murder if it is committed without premeditation in a

sudden fight in the heat of passion upon a sudden quarrel and without the offender's having

taken undue advantage or acted in a cruel or unusual manner.

Explanation, It is immaterial in such cases which party offers the provocation or commits the

first assault.

The most important element here is that there should be a fight— an offer of violence on both

sides. The exception would not be appli-cable where, in the course of a wordy quarrel, the

accused hit the deceased on the head with a lathi and killed him.

To invoke Exception 4 too Section 300,1. PC. four requirements must be satisfied, namely,

(1) it was a sudden fight,

Page 16 of 33 www. gup shup study. com

www.gupshupstudy.com CRIMINAL LAW

(2) there was no pre-meditation,

(3) the act was done in a heat of passion,

(4) the assailant had not taken any undue advantage or acted in a cruel manper. The cause

of the quarrel is not even nor is it relevant who offered the provocation or started the assault.

The number of wounds caused during the occurrence is not a decisive factor but what is

important is that the occurrence must have been sudden and unpremeditated and the

offender must not have taken any undue advantage or acted in a cruel manner. Where, on a

sudden quarrel, a person in the heat of the moment picks up a weapon which is handy and

causes injuries, one of which proves fatal, he would be entitled to the benefit to this excep-

tion provided he has not acted cruelly. (Surinder Kumar Verses Union of India, Chandigarh).

Exception 5, Culpable homicide is not murder when the person whose death is caused,

being above the age of eighteen years, suffers death or takes the risk of death with his

own consent.

Illustration, A, by instigation, voluntarily causes Z, a person under eighteen years of age, to

commit suicide. Here on account of Z's youth, he was incapable of giving consent to his own

death. A has, therefore, abetted murder.

Takes a Lenient View in Respect of Murders Committed on the Spur of the

Moment, Exception I to IV Section 300

Section 300 of the INDIAN PENAL CODE speaks of five exceptions in which, if a murder is

committed, it is treated as culpable homicide not amounting to murder. The exceptions are

justified on the ground that in such cases the deceased is equally responsible for his death.

Accordingly, the criminal liability of the accused is reduced from murder to culpable homicide

not amounting to murder punishable under Section 304, INDIAN PENAL CODE, when death

is caused,

(1) whilst the accused was deprived of the power of self control by grave and sudden

provocation.

(2) In the exercise of the right of private defence

(3) In the exercise of legal powers

(4) In a sudden fight

(5) With the consent of the deceased.

Thus the five exceptions are,

(1) Grave and sudden provocation,

Page 17 of 33 www. gup shup study. com

www.gupshupstudy.com CRIMINAL LAW

(2) Private defence,

(3) Acts of public servants,

(4) Sudden fight,

(5) Consent

Exception 1 to Section 300 (Grave and Sudden Provocation)

Culpable homicide is not murder, if, the offender on acconnf of grave and sudden provocation,

is deprived of his power of self-control and causes the death of a person who gave the

provocation or causes the death of any other person by mistake or accident.

The above exception is subject to the following provisos,

First—That the provocation is not sought or voluntarily provoked by the offender as an

excuse for killing or doing harm to any person.

Secondly—That the provocation is not given by anything done in obedience to the law, or by a

public servant in the lawful exercise of the powers of such public servant.

Thirdly—That the provocation is not given by anything done in the lawful exercise of the right

of private defence.

Explanation—Whether the provocation was grave and sudden enough to prevent the offence

from amounting to murder is a question of fact.

Dist. Between 299 (1) 304A

Causing Death by Rash or Negligent Act (Section 304A)

"Whoever causes the death of any person by doing any rash or negligent act not amounting to

culpable homicide, shall be punished with imprisonment of either description for a term which

may extend to two years, or with fine, or with both." Punishment for causing death by rash or

negligent act is either imprisonment for 2 years, or fine, or both.

This section was added by an amendment of the code 10 years after the INDIAN PENAL

CODE, was enacted. It doesn't create a new offence. It is directed at offences, which fall

outside the range of Sections 299 and 300, where neither intention nor knowledge to cause

death is present.

This section applies where there is a direct nexus between the death of a person and the rash or

negligent act. The act must be the causa causans, it is not enough that it may have been the

causa sine qua non.

This section does not apply to the following cases,

(1) death is caused with any intention or knowledge (voluntary commission of offence),

Page 18 of 33 www. gup shup study. com

www.gupshupstudy.com CRIMINAL LAW

(2) in other words, the act must not amount to culpable homicide,

(3) death has arisen from any other supervening act or intervention which could not have

been anticipated,

(4) in other words, death was not the direct or proximate result of the rash or negligent act,

(5) death occurred due to an accident (that is where an accused on dark night believing a man

to be a ghost killed him, Waryam Singh Verses Empero.

Culpable rashness consists in hazarding a dangerous or wanton act with the nowledge that it is

so, and that it may cause injury, but without intention to cause injury, or knowledge that it will

probably be caused. In other words, a rash act is primarily an overhasty act and is thus

opposed to a deliberate act, but it also includes an act which though it may be said to be

deliberate is yet done without due deliberation culpable and caution. Culpable negligence is

the gross and culpable neglect or failure to exercise that reasonable and proper care and

precaution to guard against injury either to the public generally or to a particular individual,

which having regard to all the circumstances out of which the charge has arisen, it was the

imperative duty of the accused person to have adopted (Bala Chandra Verses State of

Maharashtra).

Rashness and negligence are not the same things. Mere negligence cannot be construed to

mean rashness. Negligence is the genus of which rashness is a species. The words "rashly and

negligently" are distinguishable and one is exclusive of the other. The same act cannot be rash

as well as negligent. The rash or negligent act means the act which is the immediate cause of

death and not any act or omission which can at most be said to be a remote cause of death. In

order that rashness or negligence may be criminal it must be of such a degree as to amount to

taking hazard knowing that the hazard was of such a degree that injury was most likely to be

caused thereby. The criminality lies in running the risk or doing such an act with recklessness

and indifference to the consequences.

Contributory negligence, The doctrine of contributory negligence does not apply to the

criminal liability. Where there is ample proof that the accused had brought about the accident

by his own negligence and rashness, it matters not whether the deceased was deaf, or drunk,

or, in part contributed to his own death.

Thus, contributory negligence is no defence to a criminal charge. A criminal charge shall be

sustainable if the accused had been at fault even though someone else may have been equally

at fault. In such cases the question is, did the accused rashly or negligently do an act which

was likely to endanger the public? If he did such an act, the fact that the actual injury was

Page 19 of 33 www. gup shup study. com

www.gupshupstudy.com CRIMINAL LAW

brought about by carelessness or contribution of the victim also will be no defence.

Page 20 of 33 www. gup shup study. com

www.gupshupstudy.com CRIMINAL LAW

Page 21 of 33 www. gup shup study. com

www.gupshupstudy.com CRIMINAL LAW

Section 304B

Distinction between Section 304-B (Dowry Death) and Section 498-A (Cruelty)

The provision laid down under Section 304-B and Section 498-A are not mutually exclusive.

There is difference between these two sections, they are,

FIRST,

Under Section 304-B, the dowry death is punishable and such death should have occurred

within a period of seven years of marriage where as Under Section 498-A, the cruelty by

husband or husband's relatives is punishable but no time period of seven years has been

provided for the prosecution under this section.

SECOND,

Section 304-B is attracted When the cruelty or harassment of a married woman results in her

death where as Under Section 498-A, cruelty as such as punishable.

THIRD,

Under Section 304-B (Dowry Death), punishment may extend upto imprisonment of life with

a minimum of seven years of imprisonment where as Under Section 498-A (Cruelty),

punishment may extend upto three years of imprisonment and fine only.

FOURTH,

In Section 304-B (Dowry Death), There is no explanation which gives the meaning of 'cruelty'

where as Under Section 498-A, There is an explanation clause which gives the meaning

of'cruelty'.

However, the cruelty is a common essential ingredient to both the offences and that has to be

proved before the person is convicted. Thus, the offence being of the common background, a

person charged and acquitted under Section 304-B can be convicted under Section 498-A for a

lesser offence without charge being there, if such a case is made out.

Further, in order to avoid technical defect it is proper to frame charges under both

sections, convictions would be made under both. Separate sentence need not be awarded under

Section 498-A and under Section 304-B (Pawan Kumar Verses State of Haryana).

Page 22 of 33 www. gup shup study. com

www.gupshupstudy.com CRIMINAL LAW

Sections 319 and 320

Section 320. Grievous hurt—"The following kinds of hurt only are designated as "grievous",

—

First—Emasculation.

Secondly—Permanent privation of the sight of either eye. Thirdly—Permanent privation of the

hearing of either ear. Fourthly—Privation of any member or joint.

Fifthly—Destruction or permanent impairing of the powers of any member of joint.

Sixthly—Permanent disfiguration of the head or face. Seventhly—Fracture or dislocation of a

bone or tooth. Eighthly—Any hurt which endangers life or which causes the sufferer to be

during the space of twenty days in severe bodily pain, or unable to follow his ordinary

pursuits.

Grievous hurt is hurt of a more serious kind. Hurt or grievous hurt to be punishable must be

caused voluntarily, as defined in sections 321 and 322 of INDIAN PENAL CODE.

The Code on the basis of the gravity of the physical assault has classified hurt into simple and

grievous so that the accused might be awarded punishment commensurate to his guilt. Though

it is very difficult and absolutely impossible to draw a fine line of distinction between the two

forms of hurts—simple and grievous—with perfect accuracy, the Code has attempted to

classify certain kinds of hurt as grievous and provided for severe punishment depending upon

the gravity of the offence in question.

Thus, to make out the offence of voluntarily causing grievous hurt, there must be some

specific hurt, voluntarily inflicted, and coming within any of the eight kinds enumerated in

this section.

Emasculation means depriving a male of masculine vigour. It means to render a man impotent.

This clause is confined to males only. It means unsexing a man or depriving a man of his

virility. This clause was inserted to counteract the practice common in this country for women

to squeeze men's testicles on the slightest provocation. Emasculation may be caused in a

variety of ways. To bring the case under this clause the impotency caused must be permanent.

(1) Injury to eyesight, The second kind of grievous hurt is causing injury to eyesight.

The test of gravity is the permanency of the injury caused to one eye or both eyes.

(2) Deprivation of hearing, Causing deafness is the third kind of grievous hurt. It may be

with respect to one ear or both ears. To attract this clause the deafness caused must be

permanent.

Page 23 of 33 www. gup shup study. com

www.gupshupstudy.com CRIMINAL LAW

(3) Loss of limb or joint, Causing loss of a limb or joint is the fourth kind of grievous hurt.

The expression used in the section is deprivation of any member, section or joint, crippling a

man with life-long misery. The term member is used to mean nothing more than an organ or a

limb.

(4) Impairing of limb, Limbs and joints are essential parts of body that help in the discharge

of normal transactions incidental to ordinary life. Destruction or permanent impairing of the

powers of any member or joint is the fifth kind of grievous hurt.

Disabling is distinguishable from disfiguring as discussed in the sixth clause. To disfigure

means to cause some external injury which detracts from a person's personal appearance.

It may not weaken him. On the other hand, to disable means to do something creating a

permanent disability and not a mere temporary injury.

Disfiguration means doing some external injury to a man which detracts from his personal

appearance such as cutting of a man's nose or ears. Putting a red-hot iron on cheeks of a girl

which left permanent scars [Anta Dadoba] or cutting the bridge of nose of girl with razor

[Gangaram],

Fracture or dislocation of a bone is considered to be a grievous hurt because it causes a great

pain to the person injured. Break by cutting or spintering of the bone, rupture or fissure in

bone, partial cut of bone amounts to fracture within the meaning of this section. The throw of

wife from a window about six feet high which resulted in the fracture of the knee-pan and in

several small wounds, it was held that husband was guilty of causing grievous hurt.

Hurt which causes severe bodily pain for the period of twenty days means that person must

be unable to follow his ordinary pursuits.

The provisions contained in clause 8 of section 320, INDIAN PENAL CODE, are of a general

nature. The clause is borrowed from French Penal Code. It refers to three classes of injuries

which are not covered under any one of the above clauses 1 to 7 of the section. It labels the

following hurts as grievous, viz., those

(1) Which endangers life, or

(2) Which causes the sufferer to be during the space of 20 days in severe bodily pain, or

(3) Which causes the sufferer to be during the space of twenty days unable to follow his

ordinary pursuits.

The above three sub-clauses are independent of each other.

(1) Hurt which endangers life and an injury as is likely to cause death distinguished,

An injury is said to endanger life if it may put the life of the injured in danger. A simple injury

Page 24 of 33 www. gup shup study. com

www.gupshupstudy.com CRIMINAL LAW

cannot be called grievous simply because it happened to be caused on a vital part of the body,

unless the nature and dimension of the injury or its effects are such that in the opinion of a

qualified physician, it actually endangers the life of the victim.

There is a very thin and subtle demarcation line between 'hurt which endangers life'

(under clause 8 to section 320,indian penal code, and 'injury as is likely to cause death',

defined in section 299,indian penal code. In fact, it is very difficult to distinguish between the

two provisons and to hold a person liable under section 325, INDIAN PENAL CODE, for

causing grievous hurt, or under section 304, INDIAN PENAL CODE, for culpable homicide

not amounting to murder when the injury results in the death of the victim.

(2) Hurt which causes sufferer to be during the space of twenty days in severe bodily

pain, In view of the seriousness of the injury resulting in incapacitation of the victim for a

minimum period of twenty days the Indian Penal Code has designated such hurts as grievous

though they might not be necessarily dangerous to life.

(3) Hurt which causes the sufferer to be during the space of twenty days unable to follow

his ordinary pursuits, The mere fact that a person remained in hospital for a statutory period

of twenty days, or did not attend to his normal duty for the said period, is not in itself

sufficient to convict the accused for causing grievous hurt. It must be proved that during that

period the victim was unable to follow his ordinary pursuits. It is not legally necessary that the

injured must get himself admitted in the hospital. It is only that hurt which causes the sufferer

to be during the space of 20 days in severe bodily pain, or unable to follow his ordinary

pursuits, that will be designated as grievous. In case the effect of the hurt does not last for

twenty days, the hurt will not be designated as grievous. In Mohindar Singh Verses State of

Punjab, 1980 Punj LR 639, the accused on 22nd August, 1922 inflicted a wound on Sarwan

Singh's leg with a gandasa (a sharp-edged weapon) and gave him blows with the back of the

gandasa. Tetanus set in on 31 st August, 1922 which caused his death. Held, a wound in the

leg was not in itself sufficiently dangerous to bring the case within the meaning of grievous

hurt when death resulted due to tetanus which supervened and resulted in the death of the

deceased.

(3) Acts neither intended nor likely to cause death may amount to grievous hurt, In the

absence of intention to cause death, or knowledge that death is likely to be caused from the

harm inflicted, but death is caused, the accused could be guilty of grievous hurt only, if the

injury caused was of a serious nature.

Page 25 of 33 www. gup shup study. com

www.gupshupstudy.com CRIMINAL LAW

Page 26 of 33 www. gup shup study. com

www.gupshupstudy.com CRIMINAL LAW

Offence of Voluntarily Causing Grievous Hurt

Section 321. Voluntarily causing hurt—Whoever does any act with intention of thereby

causing hurt to any person, or with the knowledge that he is likely thereby to cause hurt to any

person, and does thereby cause hurt to any person, is said "vountarily to cause hurt". Section

322. Voluntarily causing grievous hurt—"Whoever voluntarily causes hurt, if the hurt

which he intends to cause or knows himself to be likely to cause is grievous hurt, and if the

hurt which he causes is grievous hurt, is said, "voluntarily to cause grievous hurt."

Explanation, A person is not said voluntarily to cause grievous hurt except when he both

causes grievous hurt and intends or knows himself to be likely to cause grievous hurt. But he

is said voluntarily to cause grievous hurt, if intending or knowing himself to be likely to cause

grievous hurt of one kind, he actually causes grievous hurt of another kind. Illustration

A, intending or knowing himself to be likely to permanently disfigure Z's face, gives Z a blow

which does not permanently disfigure Z's face, but which cause Z to suffer severe bodily pain

for the space of twenty days. A has voluntarily caused grievous hurt. Punishment for

voluntarily causing hurt or grievous hurt is provided under Sections 323 and 325 of INDIAN

PENAL CODE.

Difference between Kidnapping and Abduction

FIRST,

The offence of kidnapping is committed only in respect of a minor under 16 years of age, if a

male, or under 18 years of age, if a female or a person of unsound mind where as The offence

of Abduction may be committed in respect of person of any age.

SECOND,

In the offence of kidnapping the person kidnapped is removed out of lawful guardianship.

Therefore a child without guardian that is an orphan cannot be kidnapped where as The person

abducted need not be in the lawful keeping of a guardian or any body.

THIRD,

Simple taking or enticing away of a minor or a person of unsound mind constitutes

kidnapping where as In abduction force, compulsion or decietful means are used.

FOURTH,

IN kidnapping, Consent of the person taken or enticed is immaterial because they are

Page 27 of 33 www. gup shup study. com

www.gupshupstudy.com CRIMINAL LAW

incompetent to make a valid consent where as In abduction, consent of a person moved, if

freely and voluntarily given condones the offence.

FIFTH,

In Kidnapping, the intent of the kidnapper is irrelevant. (Kidnapping from lawful guardianship

is a strict liability offence) where as In abduction, intent of the offender is an important factor

because abduction by itself is not an offence unless committed with certain intent.

SIXTH,

Kidnapping is not a continuing offence because the offence is complete the moment a person

is deprived of his lawful guardianship where as Abduction is a continuing offence and the

offence of abduction continues so long as a person is moved from one place to another.

SEVENTH,

Kidnapping is a substantive offence, punishable under Section 363 OF INDIAN PENAL

CODE. Thus, Kidnapping is per se punishable where as Abduction is an auxiliary act, not

punishable by itself but made criminal only when it is done with some criminal intent

specified in Section 364-366

EIGHTH,

Kidnapping from lawful guardianship cannot be abetted where as Abduction can be abetted.

Ingredients of the Offence of Theft

QUESTION 1. Define and illustrate "theft". Point out the essential ingredients.

Answer. Theft, Whoever, intending to take dishonestly any movable property out of the

possession of any person without that person's consent moves that property in order to such

taking is said to commit theft. (Section 378). The punishment provided for it is three years

and/or fine.

In order to constitute theft the following five ingredients are necessary,

(1) Dishonest intention to take property, It is initially for the prosecution to prove that the

accused had acted dishonestly and where circumstances show that the property has been

removed in the assertion of a bona fide claim or right, it is not theft. A person can, however,

Page 28 of 33 www. gup shup study. com

www.gupshupstudy.com CRIMINAL LAW

be convicted of stealing his own property, as where A having pawned his watch to Z takes it

out of Z's possession without Z's consent, not having paid what he borrowed on the watch,

and though the watch is his own property, A commits theft as he takes it dishonestly.

Similarly, if A owes money to Z for repairing the watch, and if Z retains the watch lawfully as a

security of the debt, and A takes the watch out of Z's possession, with the intention of

depriving Z of the property as a security for his debt, he commits theft, inasmuch as he takes

it dishonestly. But if A having not owed to Z any debt for which Z could detain the watch as

security, enters the shop openly and takes his watch by force out of Z's hand. A is not guilty of

theft as he did not act dishonestly although he may have committed criminal trespass and

assault. Similarly if A, in good faith, believing a property, belonging to Z to be A's own

property, takes that property out of B's possession A, as he does not take it dishonestly, does

not commit theft. But if A takes an article belonging to Z out of Z's possession without Z's

consent, with the intention of keeping it until he obtains money from Zas a reward for its

restoration, A having taken the article dishonestly has committed theft. A servant is, however,

not guilty of theft when what he does is at his master's bidding unless he participates in his

master's knowledge of the dishonest nature of the acts. But if the servant entrusted by his

master with the care of a certain movable property runs away with it without his master's

consent the servant is guilty of theft.

(2) The property must be movable, A thing so long as it is attached to the earth, not being

movable property, is not the subject of theft, it becomes capable of being the subject of theft

when it is severed from the earth.

(3) It should be taken out of possession of another person, The property must be in the.

possession of another person from where it is removed. There is no theft of wild animals,

birds or fish while at large, but there is a theft of tamed animals. A finds a ring lying on the

high road not in the possession of any person. A, by taking it commits no theft, though he

may commit criminal misappropriation of property.

(4) It should be taken without consent of that person, The consent may be express or

implied and may be .given either of the person in possession, or by any person having for

that purpose express or implied authority. A being on friendly terms with Z, goes into Z's

library in Z's absence, and takes away a book without Z's express consent for the purpose of

merely reading it (and with the intention of returning it). Here it is probable that A may have

conceived that he had Z's implied consent to use Z's book. If this was A's impression, A has

not committed theft. A asks charity from Z's wife. She gives A money, food and clothes, which

A knows to belong to Z, her husband. Here it is probable that A may conceive that Z's wife is

authorized to give away alms. If this was A's impression. A has not committed theft. The

position is not the same if A is the paramour of Z's wife and she gives A's valuable property,

Page 29 of 33 www. gup shup study. com

www.gupshupstudy.com CRIMINAL LAW

which A knows to belong to her husband Z, and to be such property as she has not authority

from Z to give. If A takes the property dishonestly, he commits theft.

(5) There must be some removal of the property in order to accomplish the taking of it,— A

puts a bait for dogs, in his pocket, and induces Z's dog to follow it. Here, if A's intention be

dishonestly to take the dog out of Z's possession without Z's consent, A has committed theft

as soon as Z's dog has begun to follow A. Again A meets a bullock carrying a box of treasure.

He drives the bullock in a certain direction in order that he may dishonestly take the treasure.

As soon as the bullock begins to move, A has committed theft of the treasure. Similarly, A

sees a ring belonging to Z lying on a table in Z's house. Not venturing to misappropriate the

ring immediately for fear of search and detection, A hides the ring in a place where it is highly

improbable that it will ever be found by Z, with the intention of taking the ring from the hiding

place and selling it when the loss is forgotten. Here, A, at the time of first moving the ring,

commits theft.

Page 30 of 33 www. gup shup study. com

www.gupshupstudy.com CRIMINAL LAW

Distinction Between ‘Theft’, Distinction Between ‘Extortion’.

FIRST,

In theft, Offender takes the property without consent of owner where as in extortion, Offences

committed by obtaining THE consent wrongfully.

SECOND,

Theft can be committed in respect of movable property only. Where as extortion can be

committed in respect of both movable and immovable property.

THIRD,

In theft, the element of force does not exist where as extortion Committed by intentionally

putting a person in fear of injury to that person and thus inducing him to part with his property

FOURTH,

In theft, fear doesn't exist where as in extortion, fear exist.

FIFTH,

In theft, Property is not delivered by the victim himself where as in extortion; Property is

delivered by the victim himself.

Page 31 of 33 www. gup shup study. com

www.gupshupstudy.com CRIMINAL LAW

SIMILARITIES between Theft & Extortion

There is one similarity also between Theft & Extortion that is they can be committed by one

person

Extortion

QUESTION 2. Define and illustrate extortion.

Answer. Extortion, Whoever intentionally puts any person in fear of any injury to that person, or to any other,

and thereby dishonestly induces the person so put in fear to deliver any person any property or valuable

security or anything signed or sealed which may be converted into a valuable security, commits

"extortion". (Section 383)—Punishment up to three years and/or fine].

The chief elements of extortion are the intentional putting of a person in fear of injury to himself or

another and dishonestly inducing the person so put in fear to deliver to any person any property or

valuable security.

(a) A threatens to publish a defamatory libel concerning Z unless he gives him money. He thus induces Z to give

him money. A has committed extortion, (b) A threatens Z that he will keep Z's child in wrongful confinement,

unless Z will sign and deliver to A a promissory note binding Z to pay certain money to A. Z signs and delivers

the note. A has committed extortion, (c) A, by putting Z in fear of grievous hurt, dishonestly induces Z to sign or

affix his seat to a blank paper and deliver it to A. Z signs and delivers it to A. Z signs and delivers the paper to A.

Here, as the paper so signed may be converted into a valuable security, A has committed extortion.

Page 32 of 33 www. gup shup study. com

www.gupshupstudy.com CRIMINAL LAW

Page 33 of 33 www. gup shup study. com

www.gupshupstudy.com CRIMINAL LAW

Distinction between Theft and Criminal Misappropriation

FIRST,

In Theft, the offender dishonestly takes the property which is in the possession of another

person by moving it where as Criminal Misappropriation takes place even when the

possession has been innocently come, but by a subsequent change of intention or from the

knowledge of some new fact.

SECOND,

In Theft, dishonest intention is manifested by a moving of property where as In Criminal

Misappropriation, dishonest intention is carried into action by an actual misappropriation or

conversion.

THIRD,

In Theft, The object of offender is to take property which is in possession of another person by

moving the property without consent of such person where as In Criminal Misappropriation,

the offender is already in possession of the property and he is not punishable by finding or

retention of the property, further intention or knowledge is required.

FOURTH,

In Theft, Dishonest intention is sufficiently manifested by a moving of the property or the act

of taking where as Criminal Misappropriation is the subsequent dishonest intention to

misappropriate or convert to his own use, that constitutes the offence.

FIFTH,

In Theft, The moving of the property itself is an offence where as In Criminal

Misappropriation, The moving of the property may be lawful but it is subsequent intention or

knowledge that makes it an offence.

Criminal Misappropriation and Criminal Breach of Trust

Distinction between Criminal Misappropriation and Criminal Breach of Trust

FIRST,

In Criminal Misappropriation, the property comes into the possession of the offender by some

casualty or otherwise and it is misappropriated afterwards where as In Criminal Breach of

Page 34 of 33 www. gup shup study. com

www.gupshupstudy.com CRIMINAL LAW

trust, offender is lawfully entrusted with the property and he dishonestly misappropriates it.

SECOND,

In Criminal Misappropriation, there is no contractual relationship where as there is a

contractual relationship In Criminal Breach of trust.

THIRD,

Criminal Misappropriation may or may not include criminal breach of trust where as Criminal

Breach of trust includes criminal misappropriation.

Criminal Breach of Trust & cheating

Distinction between Theft and Criminal Breach of Trust

FIRST,

In Theft, there is wrongful taking of a movable property without the consent of the owner

where as in Criminal breach of trust, the property is lawfully acquired with the owner's

consent but dishonestly misappropriated by the person to whom it is entrusted.

SECOND,

In Theft, property is movable property where as in Criminal breach of trust, property may be

any property.

THIRD,

In Theft, as soon as the property is taken away dishonestly, the offence is completed where as

in Criminal breach of trust, when the offender dishonestly converts the property to his own

use, the offence is completed.

Distinction between Theft, Criminal Misappropriation and Cheating

FIRST ON THE BASIS OF INTENTION,

In theft, the intention is to take dishonestly a movable property out of the possession of

another person where as in criminal misappropriation, the intention is to dishonestly

misappropriate or convert the movable property to his own use while Cheating is fraudulently

or dishonestly inducing the deceived person to deliver any property.

SECOND ON THE BASIS OF PROPERTY,

Movable property is involved in case of theft and criminal misappropriation where as in

Page 35 of 33 www. gup shup study. com

www.gupshupstudy.com CRIMINAL LAW

cheating, property can be any property.

THIRD ON THE BASIS OF POSSESSION,

In Theft, The property is taken out of the possession of another where As in criminal misappropriation The

property is already in possession of the offender and in cheating, the victim is induced to deliver the property.

Like criminal breach of trust and misappropriation, there is wrongful gain or loss in cheating.

However, in cheating, dishonest intention starts with very inception of transaction, and in

breach of trust, the person receives property legally but retain or convert it unlawfully.

Distinction between Cheating and Extortion

FIRST,

In Cheating, consent is obtained by deception where as In Extortion, consent is obtained by

intimidation.

SECOND,

In Cheating, the person is induced by fraudulent or dishonest means to deliver the property

where as In extortion, offence is committed by putting a person in fear of injury to part with

his property by threats.

Cheating Ingredients

QUESTION 1. Explain criminal misappropriation. Distinguish it from theft.

Answer. Criminal Misappropriation, The offence of criminal misappropriation consists in

dishonest misappropriation or conversion to his own use any movable property. [Section

403], It takes place when the possession has been innocently come by, but by a subsequent

change of intention, or from the knowledge of some new fact with which the party was not

previously acquainted, the retaining becomes wrongful and fraudulent. A takes property

belonging to Z out of Z's possession in good faith believing, at the time when he takes it, that

the property belongs to himself. A is not guilty of theft, but if A, after discovering his mistake

dishonestly appropriates the property to his own use, he is guilty of an offence under Section

403 of dishonest misappropriation of property. Similarly A and B, being joint owners of a

horse. A takes the horse out of B's possession, intending to use it. Here, as A has a right to

use the horse and appropriates the whole proceeds to his own use, he is guilty of an offence

t under Section 403, I.P.C.

Explanation 1 to Section 403 provides that a dishonest misappropriation fora time only is

misappropriation within the meaning of this section. For example, A finds Government

Page 36 of 33 www. gup shup study. com

www.gupshupstudy.com CRIMINAL LAW

promissory note belonging to Z, bearing a blank endorsement, A knowing that the note

belongs to Z, pledges it with a banker as a security for a loan, intending at a future time to

restore it to Z. A has committed an offence under this section. Explanation 2 to this section

provides that a person who finds property not in the possession of any other person, and

takes such property for the purpose of protecting it for, or of restoring it to the owner, does not

take, or misappropriate it dishonestly, and is not guilty of an offence, but he is guilty of the

offence defined above, if he appropriates it to his own use, when he knows or has the means

to discovering the owner, or before he has used reasonable means to discover and give

notice to the owner and has kept the property for a reasonable time to enable the owner to

claim it.

What are reasonable means or what is a reasonable time in such a case is a question of fact.

It is not necessary that the finder should know who is the owner of the property or that any

particular person is the owner of it, it is sufficient if, at the time of appropriating it, he does not

believe it to be his own property, or in good faith believes that the real owner cannot be

found.

The charge against the accused related to preparation of false documents because even

though no work had been done and no amount had been disbursed, they prepared

documents showing the doing of that work and payment of that amount. It would be no

answer to that charge that after the matter had been reported to the higher authorities, the

accused got the rectification work done. It would also be no answer to a charge of criminal

misappropriation that the money was subsequently, after the matter had been reported to the

higher authorities, disbursed for the purpose for which it had been entrusted. According to

Explanation 1 to Section 403, INDIAN PENAL CODE, at dishonest misappropriation for a

time only is "misappropriation" within the meaning of that section. [Kandu Sonu Dhobi v.The

State of Maharashtra].

Illustrations,

(a) A finds a rupee on the high road, not knowing to whom the rupee belongs. A picks up the

rupee. Here A has not committed the offence defined in Section 403.

(b) A finds a letter on the road containing a bank note. From the direction and contents of the

letter he learns to whom the note belongs. He appropriates the note. He is guilty of an

offence of dishonest misappropriation of property under the section,

(c) A sees Z drop his purse with money in it. A picks up the purse with the intention of

restoring it to Z, but afterwards appropriates it to his own use. A has committed an offence of

dishonest misappropriation,

(d) A finds a purse with money, not knowing to whom it belongs, he afterwards discovers that

it belongs to Z, and appropriates it to his own use. A is guilty of an offence under the above

Page 37 of 33 www. gup shup study. com

www.gupshupstudy.com CRIMINAL LAW

section,

(e) A finds valuable ring, not knowing to whom it belongs. A sells immediately without

attempting to discover the owner. A is guilty of an offence under this Section.

It would thus appear from the above illustrations that the two main ingredients of the offence

are dishonest misappropriation or conversion of property for a person's own use and such

property must be movable.

The punishment prescribed for the offence is imprisonment for a term which may extend to

two years, or with fine, or with both.

DIFFERENCE BETWEEN THEFT AND CRIMINAL MISAPPROPRIATION

FIRST,

In theft, The object of offender is to take property from another person's possession, and the

offence is completed as soon as the offender has moved the property dishonestly where as

in criminal misappropriation, The offender is already in possession of the property and his

possession is not punishable either because he has lawfully obtained it, or because he has

found it, or it is a joint owner of it or has acquired it under some mistaken notion.

SECOND,

In theft, The moving of property itself is an offence where as in criminal misappropriation, The

moving of property may be perfectly lawful, it is the subsequent intention to dishonestly

misappropriate or convert it to his own use which is an offence.

THIRD,

In theft, the moving of property takes place without the consent of the owner where as in

criminal misappropriation, the possession may even be with the consent of the owner, for

example, may be a joint owner.

FOURTH,

In theft, the dishonest intention proceeds the act of taking where as criminal misappropriation

is the subsequent intention to misappropriate or convert to his own use that constitutes the

offence.

QUESTION 2. Explain criminal breach of trust. Distinguish it from (a) theft and (b) criminal

misappropriation. Answer. Criminal Breach of Trust, A person commits criminal breach of

trust if he

(1) being in any manner entrusted with property or with any dominion over property,

(2) dishonestly misappropriates or converts to his own use that property, or

Page 38 of 33 www. gup shup study. com

www.gupshupstudy.com CRIMINAL LAW

(3) dishonestly uses or disposes of that property in violation

(1) of any direction of law prescribing the mode in which such trust is to be discharged or

(2) of any legal contract, express or implied, which he has made touching the discharge of

such trust, or wilfully suffers any other person so to do. (Section 405)—Punishment three

years, fine or both.

In order to constitute legal entrustment within the meaning of Section 405, I.P.C. the following

ingredients are necessary, viz.,