Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Essay On Lying

Uploaded by

Tot EdOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Essay On Lying

Uploaded by

Tot EdCopyright:

Available Formats

General Argument Essay-Lying

Prompt: Agree, Disagree, or Qualify the claim that “the truth’s always better” than

lying

Human civilization is built on a series of moral obligations, obligations that keep

our society from descending into a state of frenzied barbarism. Many of these moral

codes can be found in the byproducts of our civilization, religion, as seen with

the principles of the ten commandments and the pillars of Islam. From these

guidelines, we have created laws binding our society in place, and we have

concluded that violations of these moral codes, such as lying, can be classified as

bad actions. The problem with this purely black and white mentality is that a gray

area can form when telling the truth may violate the other rules of our society.

For this reason, I will qualify the claim that lying is always unfavorable.

In simple situations, where lying primarily stems from personal interest and

avarice, the question of lying’s validity becomes a simple duality: lying is bad

and telling the truth will be better. This can be seen frequently in the fraud of

past political institutions. Lying destroyed the lives of the members of Harding’s

Cabinet after Teapot Dome. Lying destroyed Nixon’s career after Watergate, where he

was only saved after Ford’s pardon. Lying destroyed the lives of millions of

Chinese citizens after Mao created false promises and reports of the state of the

country. Ultimately, lying without any good reason, or lying with selfish

motivation never results in any good for either party. For the most part, these

lies serve as selfish conduits that only cause ill will for the affected. Because

humans have long associated lying as a sin, it is unlikely that history will

remember these liars kindly, and thus no one benefits.

A much harder question to answer occurs when there are multiple moral factors in

place. For example, in Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men, George lies to Lennie (George’s

mentally slow friend) about his fate, assuring Lennie that he was safe before

saving Lennie from lynching by shooting him with a shotgun. Here, the question of

lying is more dubious. Should George have told the truth to Lennie, revealing the

truth of his fate, or was George justified in lying? What makes this part difficult

is that multiple factors are in play; George knows that lying is bad, but if he

doesn’t lie, he will ruin Lennie’s ignorance, and as they say, ignorance is bliss.

The main problem is that there is no moral hierarchy established here; It’s not

clear if we should prioritize transparency over making others feel better. As a

result, this question becomes subjective and likely impossible to achieve consensus

on. These lies are often referred to as white lies, or protective lies, and their

validity will depend on the situation.

Another category of dubious lies is the truth-keeping lies or lies that form to

preserve trust or bonds. Back in 10th grade, I received knowledge of a cheating

ring, as well as an invitation to join. I refused to join, but when a teacher asked

our class if anyone had knowledge of this cheating ring, I didn’t speak up. While

telling the truth would have been the morally correct choice, destroying

established bonds and agreements would not have been morally correct either. These

lies become even more difficult to judge if they are also protective lies. Am I

going to rat out a friend for cheating on their essay to their dream college? Am I

going to reveal that a happy family with kids has a cheating spouse? Will I ruin

the grades of desperate kids who are only looking to pass the class, the class that

might be their only chance of getting into university? Once again, these lies prove

difficult to understand and to simply label as good or bad choices.

Lying is too complex of a process to simply assign a duality to. There are times

where lying is hurtful and should be avoided, but there are also times where lying

may be in the best interest for all.

You might also like

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Gender Differences in Touch Behaviour BeDocument12 pagesGender Differences in Touch Behaviour BeBrandySterling100% (2)

- Senate Bill 1564Document18 pagesSenate Bill 1564Statesman JournalNo ratings yet

- Free Lady Bird Deed FormDocument2 pagesFree Lady Bird Deed Formrosanajones50% (18)

- The Feminist Standpoint by Nancy HartsockDocument26 pagesThe Feminist Standpoint by Nancy HartsockMelissa Birch67% (3)

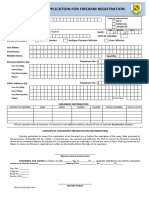

- Firearms RegistrationDocument1 pageFirearms RegistrationPAUL FRANCIS BARTOLOME0% (1)

- People Vs Echegaray DigestDocument2 pagesPeople Vs Echegaray DigestC.J. Evangelista75% (8)

- Rizal Revised9Document64 pagesRizal Revised9Princess ReyshellNo ratings yet

- A.K Gopalan V State of MadrasDocument10 pagesA.K Gopalan V State of MadrasVanshika ChoudharyNo ratings yet

- Romance of The Rose (Critical Analysis)Document3 pagesRomance of The Rose (Critical Analysis)Mark MerrillNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitDocument9 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Intercessory Prayer Guidelines For The Rescue of Nigeria PDFDocument2 pagesIntercessory Prayer Guidelines For The Rescue of Nigeria PDFAnenechukwu Anthony ikechukwuNo ratings yet

- Faculty Association of Mapua Vs CADocument1 pageFaculty Association of Mapua Vs CAlovekimsohyun89No ratings yet

- Ravenscroft Community Message - Important Information - William PendergrassDocument3 pagesRavenscroft Community Message - Important Information - William PendergrassA.P. DillonNo ratings yet

- Taifreedom News Bulletin July Vol11-Tai/englishDocument36 pagesTaifreedom News Bulletin July Vol11-Tai/englishPugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- 123Document21 pages123city campusNo ratings yet

- Fidelity Certification of TrustDocument2 pagesFidelity Certification of Trustvicki forchtNo ratings yet

- Unipolar or BipolarDocument15 pagesUnipolar or BipolarKashphia ZamanNo ratings yet

- Farinas VS ExecDocument2 pagesFarinas VS ExecVanityHugh100% (1)

- A. Bhattacharya - The Boxer Rebellion I-1Document20 pagesA. Bhattacharya - The Boxer Rebellion I-1Rupali 40No ratings yet

- Holding Hands With WampumDocument281 pagesHolding Hands With WampumElwys EnarêNo ratings yet

- James B. Henderson v. National Fidelity Life Insurance Company, 257 F.2d 917, 10th Cir. (1958)Document4 pagesJames B. Henderson v. National Fidelity Life Insurance Company, 257 F.2d 917, 10th Cir. (1958)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Public International Law - Landmark CasesDocument13 pagesPublic International Law - Landmark CasesKarla Marie TumulakNo ratings yet

- Basic DIILS Brief Slideshow May 2011Document29 pagesBasic DIILS Brief Slideshow May 2011Nancy ParvinNo ratings yet

- Air Force Instruction 11-205Document12 pagesAir Force Instruction 11-205Skipjack_NLNo ratings yet

- Voters Education (Ate Ann)Document51 pagesVoters Education (Ate Ann)Jeanette FormenteraNo ratings yet

- Parricide - An Analysis of Offender Characteristics and Crime Scene Behaviour of Adult and Juvenile OffendersDocument32 pagesParricide - An Analysis of Offender Characteristics and Crime Scene Behaviour of Adult and Juvenile OffendersJuan Carlos T'ang VenturónNo ratings yet

- Cases in Civil Procedure.1Document2 pagesCases in Civil Procedure.1Richard Jude ArceNo ratings yet

- Distress For Rent ActDocument20 pagesDistress For Rent Actjaffar s mNo ratings yet

- 12 Presumtions of CourtDocument3 pages12 Presumtions of Courtmike e100% (1)

- Romulo v. YniguezDocument19 pagesRomulo v. YniguezmehNo ratings yet