Professional Documents

Culture Documents

OECD On GST

Uploaded by

peter_martin9335Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

OECD On GST

Uploaded by

peter_martin9335Copyright:

Available Formats

2.

ENHANCING THE EFFECTIVENESS OF FISCAL POLICY

Streamlining and reforming state-federal taxation

Given the prevalence of a number of highly inefficient taxes on which states rely,

achieving a broad-based reform will require a concerted effort of the states, in close

co-ordination with the federal government. Some of the taxes on which states depend the

most, notably the payroll tax, conveyance duties, royalties, and insurance levies, are among

the most distortionary (Figure 2.4), justifying either substantially reducing their yield or

eliminating them outright. With projections pointing to rising expenditure pressures in the

coming decades, states’ access to alternative and sustainable sources of revenue will

require new fiscal federal arrangements.

One reform option deserving serious consideration is the replacement of a number of

inefficient taxes with revenue from a single and more efficient source. For instance, the

payroll tax, levied at variable rates and on different bases across states, leads to a

misallocation of labour resources and, potentially, to lower wages throughout Australia.

The tax on insurance policies raises the cost of protection against risk, and likely causes

low-income households to under-insure. The duty on conveyances of real property

substantially increases the transactions costs of property sales, discouraging mobility and

the reallocation of property to its highest valued use. Another clear motivation for

rationalising state revenue schemes is the need to address a weakness of the new resource

rent tax. As noted, the continued presence of royalties undermines the efficiency gains of

this measure.

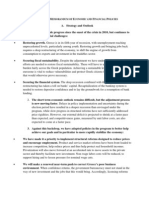

Alternatively, consideration could be given to raising the revenue yield from the Goods

and Services Tax (GST). This could provide a ready offset for lost revenue from the

elimination of less efficient state taxes and, possibly, lower personal income tax if its tax-free

threshold is raised.9 Although the GST, as an indirect invoice-credit tax, poses greater

compliance complexity than would a cash-flow tax, it has the merit of already existing and

being broadly understood. At present, the 10 per cent GST rate is low by international

comparison and it is applied to a relatively narrow base, such that, as a share of total

revenue, indirect taxes on consumption are comparatively low in Australia (Figure 2.12).

Figure 2.12. Taxes on general consumption as a percentage of total tax revenue

2007

Per cent Per cent

30 30

25 25

20 20

15 15

10 10

5 5

0 0

USA AUS CAN LUX ESP FRA GBR OECD SWE FIN MEX DNK GRC NZL PRT HUN

JPN CHE ITA KOR BEL CZE AUT NOR DEU NLD TUR SVK POL IRL ISL

Source: OECD (2009), Revenue Statistics 1965-2008.

1 2 http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/888932344577

86 OECD ECONOMIC SURVEYS: AUSTRALIA © OECD 2010

2. ENHANCING THE EFFECTIVENESS OF FISCAL POLICY

Specifically exclusions from the base include health and medical care services and supplies,

educational supplies and childcare services, and fresh food and beverages. Yet, it is widely

recognized that a broad-based tax on consumption at a single rate is highly efficient and

sustainable. Revenue gains could be achieved by broadening the base and, if necessary,

increasing its rate. Any distributional concerns from increasing the burden on low-income

households could be addressed by appropriate upward adjustments to means-tested income

support payments.

Box 2.6. Recommendations for enhancing the effectiveness of fiscal policy

Pursue efforts to improve the quality of public interventions

● Further rationalise industry subsidies. In particular phase out or reduce subsidies to the automotive

industry and to the farm sector which are ineffective and encourage poor management practices and

keep resources in potentially uncompetitive sectors. Review the effectiveness of subsidies to the housing

market, in particular the fiscal treatment favourable to individual investment in the rental sector

(“negative gearing”).

● To enhance efficiency in health care, increase resources for preventive medicine. Improve the supply

structure for elderly care and care for mental illness to reinforce efficiency, and reduce hospital costs by

promoting primary care interventions. Consider bolstering the federal government’s monopsony power over

hospitals in large agglomerations where competition is possible between multiple health care providers.

Improve fiscal governance and lessen the risk of pro-cyclicality caused by resource price changes

● Disconnect public spending decisions from fluctuations in tax revenues caused by commodity price

movements. Consider creating a reserve fund endowed with all resource tax revenues, which would be

used on a sustainable basis.

● Use the fund’s resources in line with economic developments. For instance, impose a rule to ensure that

the use of the assets of this fund, in real terms, does not increase more rapidly than the estimated trend

growth rate of the economy. Deviation from this rule would need to be justified on the basis of an

assessment of the cyclical situation, the financial position of the reserve fund and the fiscal outlook.

● Proceed with the creation of a Parliamentary Budget Office to further strengthen fiscal decision making,

perhaps including with respect to the use of resource revenues. Carefully design this new institution by

assigning it a clear mandate and guaranteeing its independence, access to information and accountability.

Proceed with tax reform in the medium term to promote labour market participation, simplify the tax

system and reduce distortions

● Streamline and reform state-federal taxation. Consider either reducing substantially or removing payroll

taxes, conveyance duties, insurance levies and royalties. Royalty payments should be eliminated rather

than reimbursed to Mineral Resource Rent Tax payers by the federal government. Apply a well-designed

resource rent tax to all commodities and all companies, irrespective of their size.

● Further reduce the corporate tax rate.

● Further lower the high effective marginal tax rate on low-income households by increasing the tax-free

threshold on personal income tax above point at which the numerous allowances and pensions cease to

be payable.

● Proceed with the rationalization and simplification of the income support system to avoid cascading and

cumulating multiple withdrawal rates. Identify possible combinations of tax schedules and transfers

that both preserve progressivity and reduce key marginal effective tax rates.

● Consider replacing inefficient state taxes and offsetting the lower corporate and personal income tax by

raising the yield for the Goods and Service Tax (GST). Increase the rate of the GST and broaden its base

to include health and medical services and supplies, educational supplies, childcare services, fresh food

and beverages. If necessary, compensate for the potentially adverse distributional effects of such a

reform by appropriate adjustments to means-tested income support payments.

OECD ECONOMIC SURVEYS: AUSTRALIA © OECD 2010 87

2. ENHANCING THE EFFECTIVENESS OF FISCAL POLICY

Notes

1. The government’s reform initiatives are based on the analysis contained in Australia’s Future Tax

System (hereafter, the AFTS), commissioned in May 2008 and released in May 2010 following a

half-year of reflection since its completion. The AFTS is the most comprehensive and forward-

looking review of Australia’s tax and transfer system in decades. The review panel’s principal

mandate was to “… position Australia to deal with its social, economic and environmental

challenges and enhance economic, social and environmental well-being” (AFTS, 2010).

2. While the vast majority of royalty payments accrue to state governments, mining companies’

profit tax payments benefit the commonwealth Treasury.

3. Indeed, the political turmoil spawned by the government’s initial proposal led eventually to the

resignation of Prime Minister Rudd and his succession by the Deputy Prime Minister in late June.

4. If the expected additional tax revenues raised by this tax in 2013-14 had been collected during the

fiscal year 2008-09, the tax rate associated with these specific levies on mining companies would

have increased from 14% to less than 21%. This would remain low by historical standards

(Figure 2.3). The impact of this tax change on the overall tax burden of the mining companies will

also be partly offset by the projected fall in the corporate tax rate.

5. The most active generation today is already affected by negative transfers since it is the first one

to pay for its own retirement, whereas it must also finance that of the previous generation via

taxes. It has also pre-financed future public-sector pensions through the creation of the Future

Fund, and it is helping to pre-finance the development of infrastructure that coming generations

will enjoy.

6. The estimated expansionary thrust of fiscal policy during the last mining boom can be measured

by an indicator of the general government balance which corrects both the effect of cyclical

variations and those stemming from the terms of trade (Turner, 2006). The decrease in this

balance, which incorporates the impact of the rise in terms of trade over their long-term average,

indicates a drop of 2% of GDP more than if gains in the terms of trade are not factored in or are not

spread through the rest of the economy. This estimation is independent of the reference period

used for the long-term value of the terms of trade (OECD, 2008).

7. In Australia, business cycles seem to be empirically better measured by the unemployment gap

than the output gap (Norman and Richards, 2010).

8. The 2008/09 budget provided the creation of three funds to invest in infrastructures (Building

Australia Fund, BAF), education (Education Investment Fund, EIF) and health (Health and Hospital Fund,

HHF). A large share of these funds (almost a total of AUD 17 billion) have been used for the stimulus

At 31 March 2010, the estimated uncommitted balance of funds was AUD 0.7 billion for the BAF,

AUD 2.7 billion for the EIF et AUD 2.9 billion for the HHF.

9. The introduction of the GST in 2000 led to the removal of some small state taxed, though not as

many as hoped.

Bibliography

AFTS (Australia’s Future Tax System) (2010), Report to the Treasurer, Part 1 and 2, December,

www.taxreview.treasury.gov.au/Content/Content.aspx?doc=html/home.htm.

Banks, G. (2009), “Back to the Future: Restoring Australia’s Productivity Growth”, Presentation to the

Melbourne Institute/Australian Economic and Social Outlook Conference, November.

Baunsgaard, T. (2001), “A Primer on Minerals Taxation”, IMF Working Paper, No. WP/01/139, September.

Boadway, R. and M. Keen (2010), “Theoretical Perspectives on Resource Tax Design”, in The Taxation of

Petroleum and Minerals: Principles, Problems and Practice, P. Daniel, M. Keen and C. McPherson (eds.),

New York: Routledge, Chapter 1.

Brown, E.C. (1948), “Business Income Taxation and Investment Incentives”, in Income, Employment and

Public Policy: Essay in Honor of Alvin Hansen, New York: Norton.

Commonwealth of Australia (2008), Budget 2008-09: Overview, Canberra.

Commonwealth of Australia (2010a), “Statement 4: Benefiting from Our Mineral Resources: Opportunities,

Challenges and Policy Settings”, Budget Strategy and Outlook 2010-11, Canberra.

Commonwealth of Australia (2010b), “Australia to 2050: Future Challenges”, The 2010 Intergenerational

Report, Canberra.

88 OECD ECONOMIC SURVEYS: AUSTRALIA © OECD 2010

You might also like

- IELTS Advantage Writing SkillsDocument129 pagesIELTS Advantage Writing SkillsJoann Henry94% (117)

- ZICA T5 - TaxationDocument521 pagesZICA T5 - TaxationMongu Rice95% (42)

- Word SmartDocument189 pagesWord SmartSmeeta Prasai0% (1)

- People v. Del RosarioDocument2 pagesPeople v. Del RosarioLyleThereseNo ratings yet

- Austria vs. NLRCDocument2 pagesAustria vs. NLRCJenilyn EntongNo ratings yet

- Value Added Tax and EVATDocument2 pagesValue Added Tax and EVATImperator FuriosaNo ratings yet

- Pte Essays With AnswersDocument19 pagesPte Essays With AnswersMani Shankar100% (3)

- France 2015 OverviewDocument57 pagesFrance 2015 OverviewjoarnNo ratings yet

- (Module10) PUBLIC FISCAL ADMINISTRATIONDocument9 pages(Module10) PUBLIC FISCAL ADMINISTRATIONJam Francisco100% (2)

- People v. de LeonDocument3 pagesPeople v. de LeonLuis LopezNo ratings yet

- Udemy Business - The Skills That Will Define The Future of HRDocument24 pagesUdemy Business - The Skills That Will Define The Future of HRJimmy ChangNo ratings yet

- Morifosque Vs People G.R. No. 156685 July 27, 2004 FactsDocument1 pageMorifosque Vs People G.R. No. 156685 July 27, 2004 FactsCedrickNo ratings yet

- Tax Reforms in PakistanDocument53 pagesTax Reforms in PakistanMübashir Khan100% (2)

- Deficit Committee PaperDocument5 pagesDeficit Committee PaperRyan DeCaroNo ratings yet

- Project Report GSTDocument36 pagesProject Report GSTshilpi_suresh70% (50)

- Questions For Question & Answer SessionDocument12 pagesQuestions For Question & Answer Sessionapi-284426542No ratings yet

- Economics Notes Year 11Document9 pagesEconomics Notes Year 11conorNo ratings yet

- A Project Report On "Goods and Services Tax in India"Document38 pagesA Project Report On "Goods and Services Tax in India"Simran KaurNo ratings yet

- Ministerial MeetingDocument7 pagesMinisterial MeetingaghaandmazaNo ratings yet

- Background and Summary of Fiscal Commission PlanDocument8 pagesBackground and Summary of Fiscal Commission PlanCommittee For a Responsible Federal BudgetNo ratings yet

- Tax and Economic Growth: Summary and Main FindingsDocument7 pagesTax and Economic Growth: Summary and Main FindingsSanjeev BorgohainNo ratings yet

- Union Budget 2010-2011: Presented byDocument44 pagesUnion Budget 2010-2011: Presented bynishantmeNo ratings yet

- Project Report GST PDFDocument36 pagesProject Report GST PDFhaz008100% (1)

- Effects Income Tax Changes Economic Growth Gale Samwick PDFDocument16 pagesEffects Income Tax Changes Economic Growth Gale Samwick PDFArpit BorkarNo ratings yet

- Project Report GSTDocument36 pagesProject Report GSThaz002No ratings yet

- En Special Series On Covid 19 Tax Policy For Inclusive Growth After The PandemicDocument14 pagesEn Special Series On Covid 19 Tax Policy For Inclusive Growth After The PandemicatescandorNo ratings yet

- Revenue Productivity of The Tax System in Lesotho Nthabiseng J. Koatsa and Mamello A. NchakeDocument18 pagesRevenue Productivity of The Tax System in Lesotho Nthabiseng J. Koatsa and Mamello A. NchakeTseneza RaselimoNo ratings yet

- Utkarsh PandeyDocument6 pagesUtkarsh Pandeyjitendra kumarNo ratings yet

- 2010 Budget HighlightsDocument5 pages2010 Budget HighlightsaryanalynnNo ratings yet

- Budget Chemistry 2010Document44 pagesBudget Chemistry 2010Aq SalmanNo ratings yet

- Highlights of Budget 2011-2012: Compiled by:-CA. Puneet Duggal (F.C.A) M/S Fatehpuria Duggal & AssociatesDocument14 pagesHighlights of Budget 2011-2012: Compiled by:-CA. Puneet Duggal (F.C.A) M/S Fatehpuria Duggal & AssociatesPuneet DuggalNo ratings yet

- Economic Survey - 2014-15 SummaryDocument41 pagesEconomic Survey - 2014-15 SummaryMohit JangidNo ratings yet

- Budget 2010 in Small Scale IndustriesDocument9 pagesBudget 2010 in Small Scale Industriesurz_spiderman2630No ratings yet

- Budget Analysis 2012Document26 pagesBudget Analysis 2012Rajpreet KaurNo ratings yet

- Business Taxation: Rachel Griffith, Helen Miller and Martin O'Connell (IFS)Document12 pagesBusiness Taxation: Rachel Griffith, Helen Miller and Martin O'Connell (IFS)anon_241413889No ratings yet

- Analysis of The Dynamic Effects of Corporation Tax ReductionsDocument36 pagesAnalysis of The Dynamic Effects of Corporation Tax ReductionsFoster SukaniNo ratings yet

- Government Tax PaperDocument40 pagesGovernment Tax PaperReggeloNo ratings yet

- BudgetDocument21 pagesBudgetPuneet KmrNo ratings yet

- Task Force Recommendation CritiqueDocument11 pagesTask Force Recommendation CritiqueAhmed Nabeel RizviNo ratings yet

- Fiscal Policy of PakistanDocument15 pagesFiscal Policy of PakistanAXAD BhattiNo ratings yet

- Taxation JunaDocument551 pagesTaxation JunaJuna DafaNo ratings yet

- India Union Budget 2011: "Quality Service Is Not What You Put Into It - It's What The Client Gets Out of It"Document41 pagesIndia Union Budget 2011: "Quality Service Is Not What You Put Into It - It's What The Client Gets Out of It"Jacob JheraldNo ratings yet

- ECO209 Present OutlineDocument3 pagesECO209 Present OutlineManda ChungNo ratings yet

- A Comprehensive Economic Reform Proposal For Laos - Philip AllanDocument11 pagesA Comprehensive Economic Reform Proposal For Laos - Philip AllanChanhsy Samavong100% (1)

- Tax PlanningDocument7 pagesTax PlanningJyoti SinghNo ratings yet

- Fiscal Policy of EUROPEDocument11 pagesFiscal Policy of EUROPEnickedia17No ratings yet

- Annex 15Document20 pagesAnnex 15Mohamed BhathurudeenNo ratings yet

- The Growing Cost of Special Business Tax Break SpendingDocument9 pagesThe Growing Cost of Special Business Tax Break SpendingShira SchoenbergNo ratings yet

- Direct Tax Reform in India: A Road Ahead: From Editor's DeskDocument4 pagesDirect Tax Reform in India: A Road Ahead: From Editor's DeskSantosh SinghNo ratings yet

- CH 1Document20 pagesCH 1tomas PenuelaNo ratings yet

- FF Pre Budget ProposalsDocument36 pagesFF Pre Budget ProposalsFFRenewalNo ratings yet

- Federal Budget 2020-21Document7 pagesFederal Budget 2020-21yiang.tranNo ratings yet

- SS Tax PlanDocument12 pagesSS Tax PlanChristianNo ratings yet

- Tax Final Discussion PaperDocument202 pagesTax Final Discussion PaperStephanie AndersonNo ratings yet

- Greece Memorandum Nr.3Document38 pagesGreece Memorandum Nr.3Michail KyriakidisNo ratings yet

- Which WACC WhenDocument6 pagesWhich WACC Whenkalyan_mallaNo ratings yet

- Minimum Alternate Tax Time To End An AssessmentDocument5 pagesMinimum Alternate Tax Time To End An AssessmentABC 123No ratings yet

- What Is Fiscal Policy?Document10 pagesWhat Is Fiscal Policy?Samad Raza KhanNo ratings yet

- RR Fixing Fiscal Policy in PakistanDocument4 pagesRR Fixing Fiscal Policy in Pakistanrimsha34602No ratings yet

- Highlights of The New Direct Tax Code: Highlights: Key Proposals For InvestorsDocument3 pagesHighlights of The New Direct Tax Code: Highlights: Key Proposals For InvestorsprabhakarladdhaNo ratings yet

- Foreword: 14/11/17, 2N15 PM Page 1 of 20Document20 pagesForeword: 14/11/17, 2N15 PM Page 1 of 20Anonymous XVUefVN4S8No ratings yet

- A Comprehensive Assessment of Tax Capacity in Southeast AsiaFrom EverandA Comprehensive Assessment of Tax Capacity in Southeast AsiaNo ratings yet

- GitAA 2015 EconomicsDocument2 pagesGitAA 2015 Economicspeter_martin9335No ratings yet

- GitAA 2015 EconomicsDocument2 pagesGitAA 2015 Economicspeter_martin9335No ratings yet

- 2014 Talent Et Al ACT Energy and Water BaselineDocument66 pages2014 Talent Et Al ACT Energy and Water Baselinepeter_martin9335No ratings yet

- Names of Exec Managers CEO and Chief ExecDocument4 pagesNames of Exec Managers CEO and Chief Execpeter_martin9335No ratings yet

- Complaint To CPA Australia PDFDocument13 pagesComplaint To CPA Australia PDFpeter_martin9335No ratings yet

- GitAA 2015 EconomicsDocument2 pagesGitAA 2015 Economicspeter_martin9335No ratings yet

- Letter From PanelDocument1 pageLetter From PanelUniversityofMelbourneNo ratings yet

- Commonwealth of Australia: The ConstitutionDocument4 pagesCommonwealth of Australia: The Constitutionpeter_martin9335No ratings yet

- Progressive SuperannuationDocument2 pagesProgressive Superannuationpeter_martin9335No ratings yet

- ACHR Paper On GP CopaymentsDocument14 pagesACHR Paper On GP CopaymentsABC News OnlineNo ratings yet

- Tony Abbott's First MinistryDocument2 pagesTony Abbott's First MinistryLatika M BourkeNo ratings yet

- GitAA 2015 EconomicsDocument2 pagesGitAA 2015 Economicspeter_martin9335No ratings yet

- CC Report PDFDocument16 pagesCC Report PDFPolitical AlertNo ratings yet

- COSTINGSDocument5 pagesCOSTINGSPolitical Alert100% (1)

- Biggest Monthly Jobs Increase in 13 Years: The Hon Bill Shorten MPDocument2 pagesBiggest Monthly Jobs Increase in 13 Years: The Hon Bill Shorten MPpeter_martin9335No ratings yet

- Opposition BudgetDocument8 pagesOpposition BudgetABC News OnlineNo ratings yet

- Baby Bonus 2 PDFDocument15 pagesBaby Bonus 2 PDFpeter_martin9335No ratings yet

- Westpac - Melbourne Institute Consumer Sentiment Index September 2013Document8 pagesWestpac - Melbourne Institute Consumer Sentiment Index September 2013peter_martin9335No ratings yet

- BabyBonus PDFDocument18 pagesBabyBonus PDFpeter_martin9335No ratings yet

- Executive AssistantDocument2 pagesExecutive Assistantapi-79262540No ratings yet

- Module 4 Fit Me RightDocument55 pagesModule 4 Fit Me RightMaria Theresa Deluna Macairan75% (4)

- Sub TopicDocument1 pageSub TopicApril AcompaniadoNo ratings yet

- Dale Carnige TTT RequirementsDocument4 pagesDale Carnige TTT RequirementskrishnachivukulaNo ratings yet

- Reading V - Customs and Warehouse ServicesDocument3 pagesReading V - Customs and Warehouse ServicesRous TobarNo ratings yet

- Mark Scheme (Results) Summer 2016: Pearson Edexcel GCE in Economics (6EC02) Paper 01 Managing The EconomyDocument18 pagesMark Scheme (Results) Summer 2016: Pearson Edexcel GCE in Economics (6EC02) Paper 01 Managing The EconomyevansNo ratings yet

- Au 3Document138 pagesAu 3Alejandra CastilloNo ratings yet

- DOT PuzzleDocument2 pagesDOT Puzzledesai628No ratings yet

- Checkpoint: Code of EthicsDocument2 pagesCheckpoint: Code of EthicsFathalla ElmansouryNo ratings yet

- Document (1) Do G FGGFDocument6 pagesDocument (1) Do G FGGFUtsha Roy UtshoNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1 and 2 Summary On LANGUAGE, CULTURE & SOCIETYDocument4 pagesLesson 1 and 2 Summary On LANGUAGE, CULTURE & SOCIETYJasper RoqueNo ratings yet

- AcknowledgementDocument6 pagesAcknowledgementGia PorqueriñoNo ratings yet

- Community Assets Mapping and SurveysDocument4 pagesCommunity Assets Mapping and SurveysabdullahNo ratings yet

- Bianchi y Bortolotti (1996) - Formal InnovationDocument18 pagesBianchi y Bortolotti (1996) - Formal InnovationIvan EspinosaNo ratings yet

- Village (NAME) Gram Panchayat (Name)Document135 pagesVillage (NAME) Gram Panchayat (Name)AmanNo ratings yet

- Citizens Charter Valenzuela CityDocument591 pagesCitizens Charter Valenzuela CityEsbisiemti ArescomNo ratings yet

- AOT Traffic Report-2018Document252 pagesAOT Traffic Report-2018Egsiam SaotonglangNo ratings yet

- Md. Fazlul Haque Additional Secretary (RTD) Ex-DG, BIAM FoundationDocument14 pagesMd. Fazlul Haque Additional Secretary (RTD) Ex-DG, BIAM FoundationAbdur RofiqNo ratings yet

- Conejo Top AttractionsDocument2 pagesConejo Top AttractionsDemnal55No ratings yet

- The Annemarie Schimmel Scholarship: Application Form 2019Document3 pagesThe Annemarie Schimmel Scholarship: Application Form 2019SidraNo ratings yet

- Field Visit Report (02-Dec-2020)Document5 pagesField Visit Report (02-Dec-2020)Ijaz AhmadNo ratings yet

- Chapter 12 Quiz 1Document4 pagesChapter 12 Quiz 1joyceNo ratings yet