Professional Documents

Culture Documents

KB

Uploaded by

khayz02Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

KB

Uploaded by

khayz02Copyright:

Available Formats

Improving the Cultural Competence of

Nursing Students: Results of Integrating

Cultural Content in the Curriculum and an

International Immersion Experience

Rosalie A. Caffrey, PhD; Wendy Neander, MN; Donna Markle, MS; and

Barbara Stewart, PhD

ABSTRACT for Nursing has required that cultural content be included

The purposes of this study were to evaluate the effect in nursing curricula since 1977, and accreditation criteria

of integrating cultural content (ICC) in an undergraduate reflect this requirement (Poss, 1999). The American Acad-

nursing curriculum on students’ self-perceived cultural emy of Nursing (1995), the American Association of Col-

competence, and to determine whether a 5-week clinical leges of Nursing (1998), and the Pew Health Professions

immersion in international nursing (ICC Plus) had any Commission (1995) have all published vision statements

additional effect on students’ self-perceived cultural com- and recommendations for the inclusion of cultural content

petence. Cultural competence was measured using a 28- in nursing and other health care provider educational pro-

item scale regarding students’ self-perceived knowledge, grams.

self-awareness, and comfort with skills of cultural com- However, cultural competence as an educational out-

petence. Pretest scores from admission into the program come has been difficult to assess. As the U.S. population

were matched with posttest scores obtained just prior to continues to grow and become more culturally diverse,

graduation for 32 students, 7 of whom also participated cultural competence has emerged as a critical element of

in a 5-week immersion experience in Guatemala. Results, professional nursing practice. A concern, then, is whether

expressed in effect sizes, showed small to moderate gains nursing education is meeting the need for preparing cul-

for the 25 students in the ICC group, and very large gains turally competent nurses.

for the 7 students in the ICC Plus group, related to per- How does one become culturally competent? Wells

ceived cultural competence. These results are consistent (2000) proposed a model that incorporates two phases—

with the two-phase (cognitive and affective) development the cognitive (acquisition of knowledge) and the affective

of cultural competence proposed by Wells. (attitudinal and behavioral changes)—in the development

of cultural competence. The cognitive phase is character-

ized by transitioning from cultural incompetence (lack

I

ntegration of cultural content into nursing education- of knowledge) to cultural knowledge, and then cultural

al programs has been a goal advocated by a number of awareness. The affective phase builds on the cognitive

nursing education organizations. The National League phase and includes the development of cultural sensitiv-

ity, cultural competence, and finally cultural proficiency.

The affective phase “requires actual experience working

Received: August 26, 2003 with diverse groups” (Wells, 2000, p. 193).

Accepted: July 14, 2004 Cultural competence, then, is an ongoing process requir-

Dr. Caffrey is Professor Emerita, Ms. Neander is Assistant Pro- ing more than formal knowledge. Values and attitudes are

fessor, and Ms. Markle is Associate Professor, Oregon Health & the foundation for a commitment to providing culturally

Science University, School of Nursing, Ashland, and Dr. Stewart is competent care, and their development requires experi-

Professor Emerita, Oregon Health & Science University, School of ences with culturally diverse individuals and communities.

Nursing, Portland, Oregon. St. Clair and McKenry (1999) do not believe cultural com-

Address correspondence to Rosalie A. Caffrey, PhD, Professor petence can be achieved without living in another culture,

Emerita, Oregon Health & Science University, School of Nursing, 1250 even if only for a short period of time. Students have lim-

Siskiyou Boulevard, Ashland, OR 97520; e-mail: caffreyr@ohsu.edu. ited ability to grasp and overcome their own ethnocentrism

234 Journal of Nursing Education

JNE0505CAFFREY.indd 234 4/22/2005 8:11:16 AM

CAFFREY ET AL.

without an opportunity to actually live in another culture. made a concerted effort to incorporate cultural concepts

Since this is not always feasible for all students, how can into course materials. This included obtaining a Fund for

cultural competence be included in the educational experi- the Improvement of Higher Education (FIPSE) 3-year

ence? What level of cultural competence should be expected North American Mobility Grant for an international ex-

of new nursing graduates? What is the added value of an change program involving two schools each in Canada,

immersion experience in international nursing? Mexico, and the United States. In addition, new faculty

Evaluation of the effectiveness of the educational pro- members with experiences in international and cross-cul-

cess on the development of cultural competence in new tural nursing were hired. Student learning experiences

graduates is needed to provide guidance in curriculum de- with Hispanic populations were expanded. More content

velopment. Students’ self-perceived knowledge, attitudes, in the form of multicultural case studies was introduced

and skills can provide a measure of their comfort with into the ongoing courses.

their learning related to cultural competence and can pro- ICC Plus. This experience was a partnership with Pueb-

vide a proxy measure of their commitment to the ongoing lo Partisans, a Canadian and U.S. nongovernmental orga-

process of becoming culturally competent practitioners. nization, recognized by the Guatemalan government as

This study was designed to accomplish two objectives: providing international assistance in the areas of health,

● Evaluate the effect of integrating cultural content agriculture, literacy, and economic development. The goal

(ICC) in an undergraduate nursing curriculum on stu- of the 5-week, 200-hour experience was the preparation of

dents’ self-perceived cultural competence. nursing professionals who were capable of collaborating

● Determine whether a 5-week clinical immersion in with and supporting a culture to promote its own health.

international nursing (ICC Plus) had any additional effect The 7 students participating in ICC Plus during the last

on students’ self-perceived cultural competence. term of their senior year worked with community-directed

initiatives for health promotion and illness prevention

METHOD across the lifespan and with general medical clinics.

Students worked in teams of 2 or 3. The clinics were

Design large, with 40 to 60 clients on average. Some clients

We used a two-group, pretest-posttest, quasi-experi- walked for up to 3 hours to reach the clinic and waited

mental design to compare students in the ICC group (n all day just to see a nurse or other health care provider.

= 25) and students in the ICC Plus group (n = 7) on per- Experienced health professionals, including Guatemalan

ceived cultural competence. health professionals, worked with students in the clinics.

Students were also exposed to and, in certain clinical set-

Sample tings, worked with traditional healers.

The sample consisted of 32 nursing students in a bacca-

laureate nursing program at a university in southern Ore- Instrument

gon. These students were admitted as juniors in 2000 and The Caffrey Cultural Competence in Healthcare Scale

graduated in 2002. Five students identified themselves as (CCCHS) was developed based on the cultural competencies

at least partially from a different ethnic group than Eu- we expected from our students on completion of our bac-

ropean American. The group contained no male students. calaureate nursing program. It was initially developed to

Of the 10 students who applied to travel to Guatemala evaluate the outcomes of the FIPSE grant. The model used

for a 5-week clinical immersion the last term of their se- in constructing the items was a rating scale of respondents’

nior year (ICC Plus), 7 were selected. Selection criteria self-perceived knowledge, self-awareness, and comfort with

included the student’s interest, the faculty’s assessment of skills of cultural competence. The statements were generic

the student’s ability to work in groups, an acceptable aca- in that they did not test knowledge, skills, or attitudes re-

demic standing, and acceptable clinical performance eval- lated to any specific cultural group. A sample item is, “In

uations. The 25 students in the ICC group continued with general, how would you evaluate your comfort level in car-

traditional senior-year clinical assignments. The students ing for clients from a culture other than your own?”

ranged in age from 20 to 44. The mean age of the students The scale contained 28 items requesting a self-rating

in the ICC Plus group (mean age = 25.3, SD = 8.7) was not on a Likert scale, with 1 = not comfortable (or not knowl-

statistically different from that of the students in the ICC edgeable or not aware) and 5 = very comfortable (or very

group (mean age = 25.6, SD = 6.5). knowledgeable or very aware) in relation to concepts ap-

propriate to cultural competence. An overall CCCHS score

Independent Variable was computed by averaging the 28 items. Items included

The independent variable included two components: the following categories:

the integration of cultural content into the undergraduate ● Knowledge about health care beliefs and practices of

nursing curriculum (ICC), and a 5-week clinical immer- a cultural group other than their own.

sion in international nursing (ICC Plus). ● Knowledge of and comfort with the cultural assess-

ICC. Southern Oregon is limited in culturally diverse ment process.

populations, thus limiting students’ exposure to culturally ● Comfort with their ability to work with a translator,

diverse clients within this region. Therefore, the faculty clients’ family members, or folk healers.

May 2005, Vol. 44, No. 5 235

JNE0505CAFFREY.indd 235 4/22/2005 8:11:18 AM

IMPROVING CULTURAL COMPETENCE

group of our FIPSE project

partner in West Virginia.

The university Institution-

al Review Board approved

the research.

Preliminary testing of

the CCCHS' reliability

and validity for detecting

change was obtained from

students involved in the

FIPSE grant. Fourteen

total matched scores were

analyzed by the paired

samples t test. Twenty-two

of the 28 items showed sig-

nificant improvement be-

tween pretest and posttest,

based on a .05 level of sig-

nificance. Cronbach’s al-

pha was .94 on the pretest

(N = 14) and .90 on the

posttest (N = 14). Based

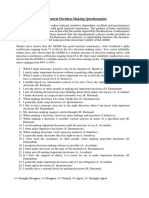

Figure 1. Comparison of changes in mean cultural competence scores of students in the ICC group on these preliminary re-

(coursework only) and students in the ICC Plus group (coursework plus immersion experience in sults, it appeared that

Guatemala). Values plotted are mean ± standard error of the mean. the CCCHS was reliable

and sensitive in detecting

improvement in students’

self-assessment of their culturally competent attitudes,

TABLE 1

knowledge, and skills following the international experi-

Number of Items Falling into Each Effect Size ences they had during their nursing program. Therefore,

Category for the ICC and ICC Plus Groups we used the CCCHS in this study to evaluate the overall

Number of Items effectiveness of our nursing education program on stu-

ICC Plus dents’ development of perceived cultural competence and

Effect Size Category ICC Group Group to further evaluate the outcomes of the Guatemala immer-

sion experience.

Very large effect (⭓ 1.00) 0 21

In this study, Cronbach’s alpha was .93 on the pretest

Large effect (.66 to .99) 1 2 (N = 44) and .97 on the posttest (N = 32). Using an inde-

Moderate effect (.36 to .65) 8 3 pendent samples t test, pretest mean scores on the overall

Small effect (.10 to .35) 12 2

CCCHS of the 7 students in the ICC Plus group (mean

= 3.19, SD = .41) and the 25 students in the ICC group

No effect (–.09 to .09) 1 0 (mean = 3.41, SD = .58) were not significantly different (p

Negative effect (⭐ –.10) 6 0 = .28). Similarly, the pretest mean scores of the two groups

Total number of items 28 28 did not differ on any of the CCCHS items.

Procedure

● Knowledge of another cultural group’s practices The pretest CCCHS was administered to 44 new juniors

around death and dying, organ donation, and pregnancy upon entry to the program. Students were asked to identify

and childbirth. a number they would recognize at the end of the program,

● Awareness of one’s own limitations related to cul- so each student’s pretest and posttest could be matched.

tural competence. The researchers had no access to student-identifying infor-

● Willingness and ability to work as a team member mation. By the end of the senior year, 32 of the original 44

with or supervise diverse staff. students could be matched with their pretest scores.

● Awareness of national policies affecting culturally

diverse populations and perceived ability to advocate on RESULTS

their behalf.

The scale was reviewed by a consultant who is an ex- At the posttest, just before graduation, the mean

pert in the culture and nursing arena, and preliminary CCCHS of the ICC group was 3.60 (SD = .59) and the mean

psychometric evaluation was performed with a student for the ICC Plus group was 4.42 (SD = .48). An F test for

236 Journal of Nursing Education

JNE0505CAFFREY.indd 236 4/22/2005 8:11:18 AM

CAFFREY ET AL.

TABLE 2

Comparison of Pretest and Posttest Cultural Competence Means and Effect Sizes for Selected CCCHS Items

ICC Group (n = 25) ICC Plus Group (n = 7)

Pretest Posttest Pretest-to- Effect Pretest Posttest Pretest-to- Effect

CCCHS Item Mean (SD) Mean (SD) Posttest r Size Mean (SD) Mean (SD) Posttest r Size

Two items with largest effect

size for the ICC Plus group

22. Ability to provide culturally 3.52 (.82) 3.64 (.76) .31 .13 2.86 (.69) 4.86 (.38) .55 3.46**

competent care.

24. Comfort supervising diverse 3.52 (1.19) 3.80 (.87) .47 .25 2.57 (1.27) 4.43 (.79) .88 2.69**

staff.

Two items with largest effect

size for the ICC group

19. Awareness of own cultural 3.24 (.93) 4.04 (.84) .42 .84** 3.43 (.79) 4.57 (.79) .08 1.07*

competence limitations.

4. Knowledge regarding risk 2.64 (.95) 3.28 (.84) .39 .64** 2.43 (.79) 4.71 (.49) –.50 2.05**

factors of another cultural

group.

Two items with largest negative

effect size for the ICC group

25. Interest in working with 4.52 (.51) 4.04 (.79) .36 –.62** 4.43 (.79) 4.86 (.34) .80 .80

diverse staff.

10. Comfort working with a 4.48 (.59) 4.08 (.86) .17 –.42* 4.43 (.53) 4.86 (.38) –.47 .54

translator.

* p < .05; ** p < .01. Significance of paired t test for pretest-to-posttest change in mean scores.

Note: Bolded values indicate reversed scores from junior to senior year.

Complete table of information for all items is available from the first author upon request.

CCCHS = Caffrey Cultural Competence in Healthcare Scale.

the groups ⫻ time interaction from a 2 ⫻ 2 repeated mea- which is considered a small-to-moderate effect size. How-

sures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare ever, adding the international immersion experience (ICC

the ICC and ICC Plus groups in terms of their change in Plus group, n = 7) improved students’ perceived cultural

overall CCCHS scores from pretest to posttest. Improve- competence by 1.23 raw score points (on a scale of 1 to 5;

ment in cultural competence on the overall CCCHS score, SD of change = .59). This corresponded to an effect size of

while demonstrated by students in both the ICC and ICC 2.07 SD, which is very large. Using these actual changes

Plus groups, was significantly greater for students in the between the ICC and ICC Plus groups to estimate the ef-

ICC Plus group (F[1, 30] = 21.2, p < .001) (Figure 1). fect size for the difference between change scores for the

two groups (effect size = 2.13) and using an alpha of .01

Effect Sizes for a one-tailed test to compare the two groups with n =

Effect sizes were then computed for each group by di- 25 (ICC group) and n = 7 (ICC Plus group), the power is

viding the mean change score (posttest minus pretest) by 89%. Conventionally, an 80% level of power is considered

the standard deviation of the change scores (Lipsey, 1990). adequate.

The advantage of an effect size is that it presents mean Effect Sizes for Item-Level Change. Because of the study’s

change in standard deviation or z-score units. We drew on exploratory nature, we also analyzed data at the item lev-

guidelines from Cohen (1988), who considered effect size el to show more clearly where change on the CCCHS was

values of .20, .50, and .80 as small, medium, and large, occurring and not occurring. As shown in Table 1, for the

respectively, and we categorized effect size values into six ICC group, no item had a very large effect size value, and

categories as shown in Table 1. only 1 item had a large effect size value (.84). Nearly three

Effect Sizes for Overall CCCHS Scores. Simply inte- fourths of the items showed either moderate or small ef-

grating cultural content in the curriculum (ICC group, n fect sizes, with a negative effect size (⭐ –.10) for 6 items,

= 25) improved students’ cultural competence by .19 raw indicating lower posttest than pretest scores. In stark con-

score points (on a scale of 1 to 5; SD of change = .46). This trast to the ICC group, the ICC Plus group had very large

raw score change corresponded to an effect size of .41 SD, effect size values (1.00 to 3.46) for 21, or three fourths,

May 2005, Vol. 44, No. 5 237

JNE0505CAFFREY.indd 237 4/22/2005 8:11:19 AM

IMPROVING CULTURAL COMPETENCE

dents improved, 11 showed

no change, and 4 worsened

on perceived cultural com-

petence. For the 25 stu-

dents in the ICC group, 11

improved, 10 showed no

change, and 4 worsened.

For the 7 students in the

ICC Plus group, 6 im-

proved, and 1 showed no

change.

DISCUSSION

Overall, students in the

ICC group demonstrated

moderate improvement in

perceived culturally com-

petent attitudes, knowl-

edge, and skills over the 2

years in the nursing pro-

gram. However, students

in the ICC Plus group

gained much more than

their classmates in their

perceived cultural compe-

tence as a result of the im-

Figure 2. Scatterplot of overall Caffrey Cultural Competence in Healthcare Scale (CCCHS) pretest mersion program.

and posttest scores for students in the ICC and ICC Plus groups. The solid line ± 2 standard errors of The item showing the

measurement indicates no change. greatest improvement for

students in the ICC Plus

of the items; all of these improvements in perceived cul- group was, “Overall, how would you evaluate your abilities

tural competence were statistically significant at p < .05. to provide culturally competent care in the clinical setting

Of the effect size values for the remaining 7 items, two to clients from a culture other than your own?” The effect

were large, three were moderate, and two were small; no size value for this item was 3.46 for students in the ICC

item had a negative effect size value for this group. For Plus group, whereas the improvement of students in the

illustration purposes, we have listed selected individual ICC group on this item was negligible (effect size = .13). In

CCCHS items in Table 2 to show the 2 items with the larg- contrast, the item with the largest effect size value for stu-

est effect size for the ICC Plus group, the 2 items with the dents in the ICC group was, “How aware do you think you

largest effect size for the ICC group, and the 2 items with are regarding your own limitations in providing cultur-

the largest negative effect size (i.e., items where perceived ally competent care to a member of a cultural group other

cultural competence worsened) for the ICC group. than your own?” (effect size = .84). For students in the

ICC Plus group, this item had an effect size value of 1.07.

Pretest to Posttest Change for Individual Students Perceived knowledge regarding risk factors of another cul-

Because change at the individual student level is im- tural group ranked second for students in the ICC group.

portant for educators, we also inspected change scores It would appear that the experiences gained by students

on the overall CCCHS to determine what percentage of in the ICC Plus group enhanced their perceived abilities

students improved, worsened, or showed no change. Un- to provide culturally competent care along with diverse

less the change exceeded two standard errors of measure- staff, while students in the ICC group became more aware

ment, the pretest to posttest difference was considered “no of their limitations and reliance on knowledge gained from

change.” The standard error of measurement was .15 on classroom content.

the scale of 1 to 5, and was estimated by multiplying the The 2 items with the largest negative effect size for stu-

SD of the pretest (.55) by the square root of 1 minus the dents in the ICC group (Table 2) are representative of the

reliability of the pretest [公1 – .93)]. Thus, we considered a 6 items for which students’ scores reversed from pretest to

pretest-to-posttest change of at least 2 ⫻ .15 (.30) as more posttest. These items all had received high pretest values

than simply measurement error. (4.08 to 4.52 on a scale of 1 to 5). These reversals indicate

As shown in Figure 2, a scatterplot of pretest and a high self-evaluation at the beginning of the program, but

posttest CCCHS scores of all 32 students, 17 total stu- perhaps reflect a more realistic view of students’ level of

238 Journal of Nursing Education

JNE0505CAFFREY.indd 238 4/22/2005 8:11:19 AM

CAFFREY ET AL.

comfort with these items as they progressed in the nurs- [United States]. Testing supplies were a luxury in Guate-

ing program. It may also reflect students’ lack of experi- mala, so a clear picture of the patient’s signs and symptoms

ence with culturally diverse clients, staff, and translators was necessary for treatment. My senses were heightened:

as, for students in the ICC Plus group, these items showed I listened, looked, touched, smelled, and intuited. Nursing

small to large gains. knowledge gained in the classroom was being applied in a

clinical setting full of families with various ailments. My

LIMITATIONS confidence grew as I recognized patient symptoms related

to certain illnesses. Using the knowledge of other nursing

Some concerns need to be addressed in examining students was equally as exciting. We were peers sharing

the results of this study. First is whether self-perceived information in an attempt to uncover the unknown. The

cultural competence has any relationship to actual prac- experience was invaluable in building confidence.

tice. This is an ongoing concern of researchers who are It is clear in the above statement that the experience

attempting to study this phenomenon. This study does not played a critical role in the students developing confidence

answer the question but only examines students’ perceived in nursing skills. More important, the results of this study

knowledge, self-awareness, and comfort with the skills of are consistent with those of St Clair and McKenry (1999)

cultural competence. How these translate into practice is regarding the importance of an international experience

unknown. in the development of cultural competence. Although cul-

Second are concerns about the small sample. However, tural awareness may develop when students interact with

the very large effect size values obtained indicate the scale culturally diverse groups in the clinical practice setting,

was sensitive enough to give valid results with this small St. Clair and McKenry (1999) found there was no change

sample. in students’ ethnocentrism if the experience did not in-

A third concern is whether the self-selection, and then clude immersion into the cultural groups’ daily reality.

final selection by faculty, of students in the ICC Plus group Ms. Rushton described the effect of this experience on her

biased the results. As noted previously, no differences ex- current practice as an RN:

isted in the pretest scores of the two groups. In fact, stu- In many ways, not speaking the language highlighted

dents in the ICC Plus group scored somewhat lower on the important issues regarding cultural differences and com-

pretest. The ages of students in the two groups were also munication problems that can exist between nurse and

comparable. patient. Even though there were cultural brokers [indi-

One factor that may well have influenced the study re- viduals who are both bilingual and knowledgeable about

sults was recognition by students in the ICC group of what the culture] assisting with translation in Guatemala, we

experiences they had missed, when students in the ICC were forced to find new ways of reaching the patient. It

Plus group returned from abroad and shared their expe- was critical that we explain our hands-on nursing assess-

riences. This may have made students in the ICC group ment in an effort to [show] respect and avoid violating

less confident in their perceived knowledge and skills re- social norms.

garding their own cultural competence. Administering the At the same time, we were learning how to create a

posttest to students in the ICC group prior to the return trusting relationship with a people [who] we did not fully

of the students in the ICC Plus group would help decrease understand culturally and [who] appeared fearful of us at

this contamination, although not completely, because the times. This task may have been as simple as making eye

students in the ICC Plus group were still communicating contact with a mother and smiling. However, more often, it

with their classmates through e-mail. entailed an array of tactics to reveal the real problem that

In addition, although we were not aware of any other, brought the patient to the clinic.

unmeasured factors that could have resulted in the im- I speak of this because it has been very useful to me in

provement in posttest scores for students in the ICC Plus my practice today. Patients are aware of how busy nurses

group, this is always a possibility. are. It is impossible not to notice the pace of a nurse, or

hear the beepers and phones ringing when the nurse is at

CONCLUSIONS the patient’s bedside. Additionally, being hospitalized is

traumatic, and fear is common. I have the gift of words in

The following communication from one of the students this country to assist in making a human connection with

in the ICC Plus group provides insight into the personal my patients. I learned in the clinical setting in Guatemala

and professional implications of the Guatemala immer- that a few extra seconds or minutes focused on the patient

sion experience (L. Rushton, personal communication, No- produces a relationship of mutual respect and trust. There

vember 19, 2002): is an art to providing undivided attention to a patient in

It was in Guatemala that I finally felt like I was apply- the midst of a busy nursing environment.

ing my nursing knowledge. This was my reflective practice Ms. Rushton described the “art” of nursing. According

clinical experience, the time that I needed to more fully to Bernal (1998), “Delivering culturally competent care is

embrace the responsibilities and knowledge of nursing. no more and no less than delivering quality holistic care to

We were practicing nursing on a basic level without the anyone regardless of ethnic or racial background, place of

modern equipment that makes life easier in this country birth or national origin” (p. 7). Bernal went on to say, “An-

May 2005, Vol. 44, No. 5 239

JNE0505CAFFREY.indd 239 4/22/2005 8:11:20 AM

IMPROVING CULTURAL COMPETENCE

other way to look at this issue is, if we, as nurses, become changes in students’ values and attitudes, which affect

more sensitive to these differences, we will deliver more their cultural competence, as evidenced by the results of

holistic, relevant care to everyone” (p. 7). this study.

CONCLUSION REFERENCES

American Academy of Nursing. (1995). Diversity, marginalization

Questions remain regarding the level of cultural com- and culturally competent health care: Issues in knowledge de-

petence that should be expected from students at gradua- velopment. Washington, DC: Author.

tion. The Wells (2000) model can be useful in helping edu- American Association of Colleges of Nursing. (1998). The essen-

tials of baccalaureate education for professional nursing prac-

cators make this decision. For those students who do not tice. Washington, DC: Author.

participate in an immersion experience with another cul- Bernal, H. (1998). Delivering culturally competent care. Connect-

ture, perhaps the cognitive level of cultural competence is icut Nursing News, 71(3), 7-8.

the best that can be expected. This would include baseline Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sci-

ences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

knowledge about cultural health care needs and practices Lipsey, M.W. (1990). Design sensitivity: Statistical power for ex-

of diverse populations and an awareness of their own limi- perimental research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

tations in providing culturally competent care. Pew Health Professions Commission. (1998). Recreating health

However, cultural competence is an ongoing process professional practice for a new century. The fourth report of the

requiring more than formal knowledge. Values and at- Pew Health Professions Commission. Retrieved November 12,

2002, from http://futurehealth.ucsf.edu/pdf_files/rept4.pdf

titudes are the foundation for a commitment to provid- Poss, J.E. (1999). Providing culturally competent care: Is there a

ing culturally competent care, and their development role for health promoters? Nursing Outlook, 47(1), 30-36.

requires experiences with culturally diverse individuals St. Clair, A., & McKenry, L.(1999). Preparing culturally competent

and communities. For those nursing education programs practitioners. Journal of Nursing Education, 38, 228-234.

Wells, M.I. (2000). Beyond cultural competence: A model for in-

that are committed to promoting cultural competence in dividual and institutional cultural development. Journal of

their students, support for an immersion clinical experi- Community Health Nursing, 17, 189-199.

ence in another country can result in dramatic affective

JNE0505CAFFREY.indd 240 4/22/2005 8:11:20 AM

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Leactur IV - Employee Testing & SelectionDocument32 pagesLeactur IV - Employee Testing & SelectionMEHWISH MAHMOOD100% (1)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Res12 Module 2Document20 pagesRes12 Module 2Yanchen KylaNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Tugas Sia 1 Sept 2Document19 pagesTugas Sia 1 Sept 2Fadli Arif SetiawanNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Corresponding Author:: Finea@uci - EduDocument55 pagesCorresponding Author:: Finea@uci - EdualainremyNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Mayer Et Al-2007 PDFDocument11 pagesMayer Et Al-2007 PDFKarsten HerrNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Initial Development of An Inventory To Assess Stress and Health RiskDocument8 pagesInitial Development of An Inventory To Assess Stress and Health RiskMayra Gómez LugoNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- MODULE 2 HandoutDocument25 pagesMODULE 2 HandoutLady Edzelle AliadoNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- GDMS FinalDocument1 pageGDMS FinalJoysri RoyNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Ahmad 2014 - The Perceived Impact of JIT Implementation On Firms Financial Growth PerformanceDocument13 pagesAhmad 2014 - The Perceived Impact of JIT Implementation On Firms Financial Growth Performanceapostolos thomasNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Validation of The Constitution in Chinese MedicineDocument15 pagesValidation of The Constitution in Chinese MedicineBắp QuyênNo ratings yet

- Validation of The Standardized Version of RQLQ Juniper1999Document6 pagesValidation of The Standardized Version of RQLQ Juniper1999IchsanNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Standardized Tests and The Diagnosis of Speech Sound DisordersDocument9 pagesStandardized Tests and The Diagnosis of Speech Sound Disordersanyush babayanNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Evaluation of The New York Posture Rating Chart For Assessing Changes in Postural Alignment in A Garment StudyDocument17 pagesEvaluation of The New York Posture Rating Chart For Assessing Changes in Postural Alignment in A Garment StudyKOTA DAMANSARA HEALTHY SPINE CARENo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Humphrey Field AnalyzerTMDocument44 pagesHumphrey Field AnalyzerTMsayumiholic890% (1)

- Therapist Nonverbal Behavior and Perceptions of Empathy, Alliance, and Treatment CredibilityDocument8 pagesTherapist Nonverbal Behavior and Perceptions of Empathy, Alliance, and Treatment Credibilityc.limaNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- E-Book Measuring EWOMDocument385 pagesE-Book Measuring EWOMToni Ahmad SubektiNo ratings yet

- Language Testing: The Testing of Listening Comprehension: An Introspective Study1Document26 pagesLanguage Testing: The Testing of Listening Comprehension: An Introspective Study1Dini HaryantiNo ratings yet

- OBE Syllabus Language and Lit AssessmentDocument13 pagesOBE Syllabus Language and Lit AssessmentJoefryQuanicoBarcebalNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Effect of Internal Control, Human Resources Competency, and Use of Information Technology On Quality of Financial Statement With Organizational Commitment As Intervening VariablesDocument8 pagesThe Effect of Internal Control, Human Resources Competency, and Use of Information Technology On Quality of Financial Statement With Organizational Commitment As Intervening VariablesInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Batangas State University: - 7. "Camille Is Hungry So She Ate in Her Favorite Restaurant."Document5 pagesBatangas State University: - 7. "Camille Is Hungry So She Ate in Her Favorite Restaurant."Christle PMDNo ratings yet

- Panas-Gen About: This Scale Is A Self-Report Measure of Affect. Items: 20Document2 pagesPanas-Gen About: This Scale Is A Self-Report Measure of Affect. Items: 20InsiyaNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Comprehensive Material For Measurement and EvaluationDocument54 pagesComprehensive Material For Measurement and EvaluationMary ChildNo ratings yet

- Self-Efficacy and Work Readiness Among Vocational High School StudentsDocument5 pagesSelf-Efficacy and Work Readiness Among Vocational High School StudentsJournal of Education and LearningNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan in English 10Document7 pagesLesson Plan in English 10IrishJaneDeJesusNo ratings yet

- Psychology ScaleDocument15 pagesPsychology ScaleAmisha MakwanaNo ratings yet

- A Systematic Meta-Review of Measures of Classroom Management in School SettingsDocument32 pagesA Systematic Meta-Review of Measures of Classroom Management in School SettingsRasec OdacremNo ratings yet

- Psychological Assessment - Reliability & ValidityDocument56 pagesPsychological Assessment - Reliability & ValidityAlyNo ratings yet

- Using Routine Comparative Data To Assess The Quality of Health Care: Understanding and Avoiding Common PitfallsDocument7 pagesUsing Routine Comparative Data To Assess The Quality of Health Care: Understanding and Avoiding Common Pitfallsujangketul62No ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- 222 ClassX Psychology English Part1Document243 pages222 ClassX Psychology English Part1Sundeep YadavNo ratings yet

- The Korean Version of The Fugl-Meyer AssesmentDocument16 pagesThe Korean Version of The Fugl-Meyer AssesmentEkaNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)