Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Angela Logomasini - Interstate Waste Commerce

Uploaded by

Competitive Enterprise InstituteOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Angela Logomasini - Interstate Waste Commerce

Uploaded by

Competitive Enterprise InstituteCopyright:

Available Formats

Interstate Waste Commerce

Angela Logomasini

For more than two decades, various states Legislative History

and localities have battled over interstate and

intrastate movements of municipal solid waste. Congress has attempted to deal with this

States have passed import bans, out-of-state issue on several occasions, starting with the

trash taxes, and other policies to block imports. 1992 attempt to reauthorize the Resource

Localities have passed laws preempting the Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA). Bills

movement of wastes outside their boundaries dealing with interstate commerce and flow

for disposal under so-called flow-control laws. control have been advanced during every

Federal courts have struck down both types of Congress since 1992, but none have passed

laws as protectionist policies that violate the into law. The issue heated up in the late 1990s

U.S. Constitution’s Commerce Clause, which when New York City decided to send increas-

gives only Congress the authority to regulate ing amounts of waste to Virginia for disposal.

interstate commerce. Yet some federal lawmak- When localities agreed to take the waste to

ers want to pass a federal law to give states the collect “host fees,” state legislators objected. As

authority to regulate trade in the waste disposal a result, several bills were introduced in Con-

industry. gress that would institute complicated schemes

202-331-1010 • www.cei.org • Competitive Enterprise Institute

The Environmental Source

under which state lawmakers could regulate 1994, the Supreme Court ruled in C & A Car-

waste imports and flow control.1 Since then, bone Inc. v. Town of Clarkston, NY that solid

members of Congress have continued to in- waste flow-control laws were unconstitutional

troduce legislation to regulate interstate waste because they violated the Commerce Clause.3

disposal. In 2005, Rep. Jo Ann Davis (R-VA) Carbone has resulted in more economically

introduced H.R. 274, which allows shipments sound public policy. Flow-control laws forced

to “host communities,” but it applies needless trash haulers to take wastes to the most expensive

regulatory red tape and bureaucracy that could facilities. As a result, the public faced higher dis-

complicate such agreements. posal costs, and cities were encouraged to invest

in inefficient and otherwise uncompetitive waste

Host Communities disposal facilities. After Carbone, many localities

argued that they needed flow-control laws to

In recent years, many communities chose to protect their investments in government-bonded

host regional landfills, agreeing to allow waste facilities that were built with the assumption that

imports in exchange for free trash disposal and localities could ensure revenues by directing all

a cut of the landfill profits. These agreements waste business to those facilities. They claimed

have enabled communities nationwide to cut that these plants would go out of business and

taxes, repair and upgrade infrastructure, give their communities would pay high taxes to cover

pay raises to teachers, and build schools and the debt. In an open market, some firms go out

courthouses, as well as close and clean up old, of business when they are not efficient. That is

substandard landfills.2 considered a good thing because it means only

the best providers survive. However, Carbone did

Flow Control not result in this alleged financial “disaster.”

Communities benefit from a competitive

The debates over interstate waste became environment because they must find ways to

more complicated when the Supreme Court compete with more efficient operations, and

ruled on the constitutionality of solid waste haulers may conduct business with the lowest-

flow-control ordinances. Local governments cost providers. Under these circumstances, lo-

passed these ordinances to mandate that haul- calities must make sounder decisions based on

ers take all trash generated within the locality’s market realities, which helps their constituents

jurisdiction to government-designated facilities. avoid more faulty government investments.4

Bureaucrats used these ordinances to prevent

competition with facilities that local govern- 3. C & A Carbone Inc. v Town of Clarkstown, NY, 511

ments owned or backed with bonds. But in U.S. 383 (1994).

4. For a more detailed discussion of the problems with

flow control, see Jonathan Adler, “The Failure of Flow

1. For a more complete overview of these bills, see Control,” Regulation 2 (1995); National Economic Re-

Angela Logomasini, Trashing the Poor: The Interstate search Associates, The Cost of Flow Control (Washington,

Garbage Dispute (Washington, DC: Competitive En- DC: National Economic Research Associates, 1995); and

terprise Institute, 1999), 11–14. http://www.cei.org/gen- Angela Logomasini, Going against the Flow: The Case for

con/025,01659.cfm. Competition in Solid Waste Management (Washington,

2. For a sampling of such benefits, see Logomasini, DC: Citizens for a Sound Economy Foundation, 1995),

Trashing the Poor. http://www.heartland.org/Article.cfm?artId=4026.

Competitive Enterprise Institute • www.cei.org • 202-331-1010

Solid and Hazardous Waste

However, a 1997 Supreme Court case under- • People should be concerned about truck

cut Carbone to a limited extent. In 2007 the court safety—particularly those in the industry

ruled in United Haulers v. Oneida-Herkimer who drive the trucks and employ others

Solid Waste Management Authority that lo- who do—but the problems were not as se-

calities could direct waste to government-owned vere as suggested.

landfills or other disposal facilities. Because most • During the 1999 government investigation,

landfills are privately owned, this ruling has lim- of the 417 trucks stopped and inspected in

ited impact, but unfortunately, may encourage the District of Columbia, Maryland, and

governments to invest in new, inefficient govern- Virginia, 37 experienced violations. That

ment facilities so that they can essentially operate number represented a 9 percent violation

a garbage disposal monopoly, which will likely rate––an above average performance, con-

be needlessly costly to taxpayers. sidering the 25 percent rate nationwide.6

• Virginia’s “solution” to the traffic problem–

Public Safety –banning garbage barges––could put more

truckers on the road and prevent industry

During 1999, public officials claimed that re- from using a safer transportation option.

gional landfills posed a host of health and safety • Barges not only reduce traffic; they also

problems. The landfills allegedly would lead carry cargo nine times farther using the

to cancer clusters in the future. Officials in the same amount of energy, emit less than one-

District of Columbia, Maryland, and Virginia seventh of the air pollution, and have the

conducted an investigation of trucks transport- fewest accidents and spills of any other mode

ing waste from state to state, which they alleged of transportation, according to a 1994 U.S.

showed that transporting wastes created severe Department of Transportation study.7

highway hazards. They also argued that garbage • Medical waste is not more dangerous than

barges were not a safe means of transporting the household waste. According to the Centers

waste because waste would allegedly spill and for Disease Control and Prevention, “medi-

pollute waterways. Finally, they claimed that cal waste does not contain any greater

medical waste was being dumped illegally into

Virginia landfills, thereby creating dire health

hazards. All these claims proved specious: pal Landfills Based on U.S. Environmental Protection

Agency Techniques,” Waste Management and Research

• Rather than increasing public health and 10 (1992): 505–16. For some additional facts on landfill

risks, see the policy brief titled “Solid Waste Manage-

safety risks, these landfills enable communi- ment.” See also Logomasini, Trashing the Poor, 18–20.

ties to close substandard landfills and con-

6. Craig Timber and Eric Lipton, “7 States, D.C., Crack

struct safe, modern landfills. Down on Trash Haulers,” Washington Post, February 9,

• It is estimated that modern landfills pose 1999, B1. See also Motor Carrier Safety Analysis, Facts

cancer risks as small as one in a billion, an & Evaluation 3, no. 3 (Washington, DC: U.S. Depart-

extremely low risk level.5 ment of Transportation, 1998).

7. U.S. Department of Transportation, U.S. Maritime

Administration, Environmental Advantages of Inland

5. Jennifer Chilton and Kenneth Chilton, “A Critique Barge Transportation (Washington, DC: Department of

of Risk Modeling and Risk Assessment of Munici- Transportation, 1994).

202-331-1010 • www.cei.org • Competitive Enterprise Institute

The Environmental Source

quantity or different type of microbiologic the progress that the private sector has made.

agents than residential waste.”8 These policies will mean a return to a system

in which lawmakers impede market efficien-

Finally, one key concern raised by the land- cies, thereby increasing costs and reducing

fill debates involves the externalities landfills economic opportunity. Those who will feel

create for people who live either near them or the real pain of these policies will be the many

along transportation routes. Clearly, problems poor, rural communities that desperately seek

can arise, and lawmakers should be concerned ways to improve their infrastructure and qual-

about odors, litter, and traffic. These are the ity of life.

real issues that demand local government at-

tention, requiring trespass and local nuisance Key Expert

laws.9 However, these local concerns are not an

excuse to ban free enterprise in any industry. Angela Logomasini, Ph.D., Director of Risk

and Environmental Policy Competitive Enter-

Conclusion prise Institute, alogomasini@cei.org.

Public officials need to learn that the Recommended Readings

best way to manage our trash is to stop try-

ing to micromanage the entire trash disposal Logomasini, Angela. 1999. Trashing the Poor:

economy. In recent years, market forces have The Interstate Garbage Dispute. Washing-

begun to correct many of the problems caused ton, DC: Competitive Enterprise Institute.

by faulty government planning schemes. With http://www.cei.org/gencon/025,01659.cfm

the Supreme Court restoring competition, the ———. 1995. Going against the Flow: The

resulting trade has proved beneficial to both Case for Competition in Solid Waste Man-

host communities and states that lack landfill agement. Washington, DC: Citizens for a

capacity. Allowing states to impose import Sound Economy Foundation. http://www.

limits or flow-control laws will only turn back heartland.org/Article.cfm?artId=4026.

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Per-

spectives in Disease Prevention and Health Promotion

Summary of the Agency for Toxic Substances and Dis-

ease Registry Report to Congress: The Public Health Im-

plications of Medical Waste,” Morbidity and Mortality

Weekly Report 39, no. 45 (1990): 822–24.

9. See Bruce Yandle, Common Sense and Common

Law for the Environment (Lanham, MD: Rowman and

Littlefield, 1997). Updated 2008.

Competitive Enterprise Institute • www.cei.org • 202-331-1010

You might also like

- CEI Planet Spring 2019Document16 pagesCEI Planet Spring 2019Competitive Enterprise InstituteNo ratings yet

- CEI Planet Summer 2018Document16 pagesCEI Planet Summer 2018Competitive Enterprise InstituteNo ratings yet

- CEI Planet Winter 2019Document16 pagesCEI Planet Winter 2019Competitive Enterprise InstituteNo ratings yet

- CEI Planet Fall 2015Document16 pagesCEI Planet Fall 2015Competitive Enterprise InstituteNo ratings yet

- CEI Planet Summer 2015Document16 pagesCEI Planet Summer 2015Competitive Enterprise InstituteNo ratings yet

- CEI Planet Fall 2018Document16 pagesCEI Planet Fall 2018Competitive Enterprise InstituteNo ratings yet

- CEI Planet Spring 2018Document16 pagesCEI Planet Spring 2018Competitive Enterprise InstituteNo ratings yet

- CEI Planet Summer 2015Document16 pagesCEI Planet Summer 2015Competitive Enterprise InstituteNo ratings yet

- Aimee Barnes EmailDocument30 pagesAimee Barnes EmailCompetitive Enterprise InstituteNo ratings yet

- CEI Planet Spring 2015Document16 pagesCEI Planet Spring 2015Competitive Enterprise InstituteNo ratings yet

- CEI Planet Winter 2015 PDFDocument16 pagesCEI Planet Winter 2015 PDFCompetitive Enterprise InstituteNo ratings yet

- Sam Ricketts EmailDocument30 pagesSam Ricketts EmailCompetitive Enterprise InstituteNo ratings yet

- CEI Planet Winter 2018Document16 pagesCEI Planet Winter 2018Competitive Enterprise InstituteNo ratings yet

- CEI Planet Fall 2015Document16 pagesCEI Planet Fall 2015Competitive Enterprise InstituteNo ratings yet

- CEI Planet Fall 2017Document16 pagesCEI Planet Fall 2017Competitive Enterprise InstituteNo ratings yet

- CEI Planet - Spring 2017Document16 pagesCEI Planet - Spring 2017Competitive Enterprise InstituteNo ratings yet

- CEI Planet Winter 2015 PDFDocument16 pagesCEI Planet Winter 2015 PDFCompetitive Enterprise InstituteNo ratings yet

- Aimee Barnes EmailDocument1 pageAimee Barnes EmailCompetitive Enterprise InstituteNo ratings yet

- CEI Planet - Spring 2016Document16 pagesCEI Planet - Spring 2016Competitive Enterprise InstituteNo ratings yet

- Sam Ricketts EmailDocument2 pagesSam Ricketts EmailCompetitive Enterprise InstituteNo ratings yet

- CEI Planet - Fall 2015Document16 pagesCEI Planet - Fall 2015Competitive Enterprise InstituteNo ratings yet

- CEI Planet - Summer 2015Document16 pagesCEI Planet - Summer 2015Competitive Enterprise InstituteNo ratings yet

- CEI Planet - Winter 2015Document16 pagesCEI Planet - Winter 2015Competitive Enterprise InstituteNo ratings yet

- CEI Planet - Fall 2015Document16 pagesCEI Planet - Fall 2015Competitive Enterprise InstituteNo ratings yet

- CEI Planet - Summer 2017Document16 pagesCEI Planet - Summer 2017Competitive Enterprise InstituteNo ratings yet

- CEI Planet - Summer 2016Document16 pagesCEI Planet - Summer 2016Competitive Enterprise InstituteNo ratings yet

- CEI Planet - Fall 2016Document16 pagesCEI Planet - Fall 2016Competitive Enterprise InstituteNo ratings yet

- CEI Planet - Spring 2015Document16 pagesCEI Planet - Spring 2015Competitive Enterprise InstituteNo ratings yet

- CEI Planet - Winter 2016Document16 pagesCEI Planet - Winter 2016Competitive Enterprise InstituteNo ratings yet

- CEI Planet - Fall 2014Document16 pagesCEI Planet - Fall 2014Competitive Enterprise InstituteNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- 2nd Amended Class Complaint v. InfosysDocument37 pages2nd Amended Class Complaint v. Infosysmbrown708No ratings yet

- Precedents Concept and KindsDocument12 pagesPrecedents Concept and Kindsgagan deepNo ratings yet

- Republic V Bibonia DigestDocument2 pagesRepublic V Bibonia DigestHeart NuqueNo ratings yet

- Circle FinalDocument12 pagesCircle FinalArslanNo ratings yet

- Chennai Police RTI Manual Particulars of Organization, Functions and DutiesDocument59 pagesChennai Police RTI Manual Particulars of Organization, Functions and DutiesPonkarthik KumarNo ratings yet

- A Petition For Divorce by Mutual Consent Us 13 (B) of The Hindu Marriage Act, 1955-1106Document2 pagesA Petition For Divorce by Mutual Consent Us 13 (B) of The Hindu Marriage Act, 1955-1106Akash Kumar ShankarNo ratings yet

- Republic Vs Provincial Govt of Palawan GR No 170867 Dec 4 2018Document99 pagesRepublic Vs Provincial Govt of Palawan GR No 170867 Dec 4 2018JURIS UMAKNo ratings yet

- The Legal Services Authority Act, 1987Document75 pagesThe Legal Services Authority Act, 1987AbhiiNo ratings yet

- PA Law Grants Promotions in Rank To Terrorist Prisoners From PA Security ServicesDocument4 pagesPA Law Grants Promotions in Rank To Terrorist Prisoners From PA Security ServicesKokoy JimenezNo ratings yet

- State-Sponsored Forced Labor: Comparing Cases of Uzbekistan and North KoreaDocument9 pagesState-Sponsored Forced Labor: Comparing Cases of Uzbekistan and North KoreaDG YntisoNo ratings yet

- Carabeo Vs SandiganbayanDocument2 pagesCarabeo Vs SandiganbayanVane RealizanNo ratings yet

- 2021-06-07 Yoe Suárez Case UpdateDocument1 page2021-06-07 Yoe Suárez Case UpdateGlobal Liberty AllianceNo ratings yet

- The Early ProblemsDocument12 pagesThe Early ProblemsYasir Khan RajNo ratings yet

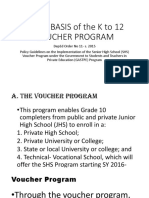

- K to 12 Voucher Program Legal BasisDocument9 pagesK to 12 Voucher Program Legal BasisLourdes Libo-onNo ratings yet

- United States v. SCRAP: 412 U.S. 669 (1973) : Justia US Supreme Court CenterDocument4 pagesUnited States v. SCRAP: 412 U.S. 669 (1973) : Justia US Supreme Court CenterSeok Gyeong KangNo ratings yet

- Minutes of The Meeting - 2ND Regular MeetingDocument3 pagesMinutes of The Meeting - 2ND Regular MeetingMarienel Odacrem Orrapac100% (1)

- Chris Abbott - CV and List of PublicationsDocument5 pagesChris Abbott - CV and List of PublicationsChris AbbottNo ratings yet

- Huur Gaat Voor Koop - FinalDocument17 pagesHuur Gaat Voor Koop - FinalSam_e_LeeJones_649380% (5)

- National Committee On United States-China Relations - Annual Report 2008Document33 pagesNational Committee On United States-China Relations - Annual Report 2008National Committee on United States-China RelationsNo ratings yet

- MEA CPIOandFAA List2021Document56 pagesMEA CPIOandFAA List2021Himanshu GuptaNo ratings yet

- Oriental Vs OccidentalDocument5 pagesOriental Vs Occidentalsirsa11100% (1)

- United Republic of Tanzania enDocument102 pagesUnited Republic of Tanzania enAbbaa BiyyaaNo ratings yet

- COMELEC Upholds Disqualification of Philippine Mayor Due to Defective COC AffidavitDocument13 pagesCOMELEC Upholds Disqualification of Philippine Mayor Due to Defective COC AffidavitellaNo ratings yet

- Turkish Visa RequirementsDocument2 pagesTurkish Visa RequirementsKim Laurente-Alib50% (2)

- University of Gondar: K.T. MuluyeDocument14 pagesUniversity of Gondar: K.T. Muluyeyedinkachaw shferawNo ratings yet

- Morusoi Right 2017Document460 pagesMorusoi Right 2017Tatiana NaranjoNo ratings yet

- Ang Tibay Vs CIRDocument2 pagesAng Tibay Vs CIRNyx PerezNo ratings yet

- (WMW) Misaalefua v. United States Postal Service - Document No. 4Document5 pages(WMW) Misaalefua v. United States Postal Service - Document No. 4Justia.comNo ratings yet

- HT Chandigarh - (2019-08-17)Document68 pagesHT Chandigarh - (2019-08-17)Mohd AbbasNo ratings yet

- Certified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsDocument2 pagesCertified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsSunStar Philippine NewsNo ratings yet