Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Teaching Rimes With Shared Reading

Uploaded by

roylepayneOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Teaching Rimes With Shared Reading

Uploaded by

roylepayneCopyright:

Available Formats

S TEACHING T

TIP IPS

I NG TE

CH A CH

IN G T ING

IPS TEACH

ching rimes with shared r

Tea eadin

g

SHARON RUTH GILL doi:10.1598/RT.60.2.9

Star light, star bright shared reading, its benefits to children’s literacy

First star I see tonight development, and ways to explicitly teach reading

I wish I may and writing behaviors, skills, and strategies.

I wish I might

While shared reading has been described as

one of the basic components of a comprehensive

Have the wish I wish tonight.

literacy program (Routman, 1999), its usefulness

“Do you ever wish upon a star? I used to make a wish in teaching word-recognition strategies (such as

on the first star I saw in the evening, and I’d say this phonics) has not always been recognized. Since the

rhyme. Can you read it with me? Let’s have the boys National Reading Panel’s (National Institute of

read the first line and the girls read the second, and Child Health and Human Development, 2000) re-

so on.... Who wants to read it all by yourself? What do

port concluded that systematic phonics instruction

you notice about the poem?”

produces significant benefits for students in kinder-

garten through sixth grade and for students having

M

y second-grade students and I read and

difficulty learning to read, phonics has received

reread poems like this one every morn-

renewed attention. The panel also found that no

ing. Daily shared reading of poems,

one method of teaching phonics was proven supe-

songs, and chants provides students with enjoy-

rior to any other. They suggested that teachers

able, successful reading experiences, and it can be

make sure that students understand the purpose of

the basis of skills lessons in the context of real learning letter sounds and that students are able to

reading. apply what they have learned. Teaching phonics in

the context of shared reading has the benefit of

showing students how phonics knowledge is used

What is shared reading? in the context of real reading. Shared reading has

Shared reading, also called shared book expe- been recommended for English as a second lan-

rience, was invented by Holdaway (1979) as a way guage learners (Drucker, 2003) and for struggling

to re-create in the classroom the one-on-one read- readers (Allington, 2001).

ing experiences children have when they are read

to by a parent. Children being read to at home can

see the text; they interact with it as they point out Why teach rimes?

what they notice and ask questions. These children Rimes are spelling patterns or “chunks” such as

learn to associate books with pleasure. In shared -ate, -ile, and -ake. One-syllable words can be di-

reading, large texts allow an entire class to see the vided into onsets and rimes; the onset is the letter or

text as they read along with the teacher. Shared letters before a vowel, while the rime is the vowel(s)

reading provides repeated readings of predictable and letters following it. For example, in the word

texts and poems, building students’ sight-word vo- plate, pl is the onset, and -ate is the rime. Teaching

cabularies, fluency, and phonics knowledge dur- onsets and rimes is a better approach to phonics

ing enjoyable and successful reading experiences. than teaching individual letter sounds because on-

Parkes (2000) provided a complete description of sets and rimes are much more consistent than single

TEACHING TIPS 191

PS TEACHIN

I NG TI G T

IPS

H

AC TEA

TE CHI A

NG TIPS TE

letters. The letter o, for example, can make a vari- might ask for volunteers to read it alone. Usually my

ety of sounds, as in hot, come, and cone. Clymer struggling readers will volunteer, because by this

(1963) found that many of the phonics rules tradi- time they can read the poem perfectly.

tionally taught are not reliable; only half of the vow-

el generalizations he tested worked at least 60% of Step 2: Introducing a skill

the time. Rimes, like -all, however, almost always After repeated readings of the poem, skills les-

make the same sound. Furthermore, Moustafa’s sons can be taught. Poems that rhyme lend them-

(1997) research showed that children tend to figure selves particularly to the study of rimes. After a

out new words by analogy—that is, by thinking of shared reading of “Star Light, Star Bright,” I ask

other similar words they know. Students who learn students what words in the poem sound the same,

a rime can apply this knowledge to help them figure or rhyme. As they identify the rhyming words, I

out new words. Research has shown that beginning write them down on a piece of poster board, one di-

and dyslexic readers benefit from being taught to rectly underneath the other. I might write the letters

decode by rime analogy (Goswami, 2000). Wylie of the rime -ight in a different color, or I might have

and Durrell (1970) identified 37 rimes (they called students place highlighter tape over the rime in

them phonograms) that can be found in 500 primary each word. My purpose is to help students notice

words. These 37 rimes can be used as a basis for the spelling pattern and learn the sound made by

shared reading lessons (see Table 1). I have also de- the -ight chunk. I ask students for other words that

signed lessons on vowel digraphs such as ou and oi also rhyme, and we add them to our list. Of course,

for shared reading. not all words that rhyme with light and bright have

the same spelling pattern. If a student says “White,”

I say, “That’s great! I’m going to put it in another

Five steps for shared reading row because white sounds the same but it is spelled

a different way.” And I begin a row with -ite words.

Step 1: Reading the poem Students quickly learn that there can be more than

In shared reading, the teacher begins with an in- one way to spell a particular sound because English

troduction that might include reading the title and is an odd language. Finally, I place the -ight poster

author’s name, asking students questions to build on our wall for further reference.

interest or activate their background knowledge, and

having students make predictions. The teacher reads Step 3: Working with words

the text first, pointing to each word. The students Next, I provide students with a hands-on ac-

join in on subsequent readings. Reading continues as tivity that provides more opportunities to work

long as the enjoyment is maintained. I might divide with -ight words. For example, I might give each

my second graders into two groups to take turns student a copy of the poem with the lines out of

reading every other line, or I might have half the sequence. The students cut the lines apart and put

class read a poem while the other half add motions. them back in the correct order. (We might also do

When the poem is very familiar to all the students, I this activity as a group using a pocket chart and

sentence strips.) Or students might use letter cards

to build -ight words as I call them out. (We might

also do this activity as a group using transparent

or magnetic letter tiles.) In a similar manner, stu-

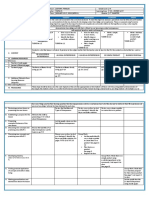

TABLE 1 dents could write -ight words on small dry-erase

37 rimes boards or chalkboards.

-ack, -ail, -ain, -ake, -ale, -ame, -an, -ank, -ap, -ash, -at,

-ate, -aw, -ay Step 4: Writing

-eat, -ell, -est Many poems make good models for students’

-ice, -ick, -ide, -ight, -ill, -in, -ine, -ing, -ink, -ip, -it writing. Often, we write class and individual poems

-ock, -oke, -op, -ore, -ot

-uck, -ug, -ump, -unk based on the structure of our shared reading poem.

Poems may also suggest writing topics. For exam-

192 The Reading Teacher Vol. 60, No. 2 October 2006

S TEACHING T

TIP IPS

I NG TE

H A CH

AC IN G T ING

IPS TEACH

ple, after reading “Star Light, Star Bright,” students References

may want to write about what they would wish for. Allington, R.L. (2001). What really matters for struggling

readers. New York: Longman.

Clymer, T. (1963). The utility of phonic generalizations in the

Step 5: Rereading primary grades. The Reading Teacher, 16, 252–258.

Once we have read a poem, the poster goes Drucker, M.J. (2003). What reading teachers should know

into a box, to be taken out and read again by re- about ESL learners. The Reading Teacher, 57, 22–29.

quest during shared reading time. Students also Goswami, U. (2000). Phonological and lexical processes. In

M.L. Kamil, P.B. Mosenthal, R. Barr, & P.D. Pearson,

choose poems from the box to read during

(Eds.), Handbook of reading research (Vol. 3, pp.

Sustained Silent Reading. I also create a poem 251–267). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

notebook for each student, into which each new Holdaway, D. (1979). The foundations of literacy. New York:

poem is added. On occasion, we take time to read Ashton Scholastic.

or illustrate some of the poems in our collections. Moustafa, M. (1997). Beyond traditional phonics. Portsmouth,

These rereadings build fluency and provide repeat- NH: Heinemann.

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

ed opportunities to read texts containing the rime.

(2000). Report of the National Reading Panel. Teaching

Once students have learned a rime, I remind children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the sci-

them to use this knowledge. When a student is entific research literature on reading and its implications

reading to me and hesitates at a word with a rime for reading instruction (NIH Publication No. 00–4769).

we have studied, I remind that student, “That word Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

looks like another word we know.” If needed, they Parkes, B. (2000). Read it again! Revisiting shared reading.

York, ME: Stenhouse.

can consult our rime posters. Shared reading has

Routman, R. (1999). Conversations: Strategies for teaching,

been a powerful teaching tool in my classroom for learning, and evaluating. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

helping children enjoy reading and for building flu- Wylie, R.E., & Durrell, D.D. (1970). Teaching vowels through

ency and skills. phonograms. Elementary English, 47, 787–791.

Gill teaches at Murray State University (Early To submit Teaching Tips, see instructions for authors at www.

Childhood and Elementary Education, 3207 reading.org. Teaching Tips should be brief, with a single focus on

Alexander Hall, Murray, KY 42071, USA). the classroom.

E-mail sharon.gill@coe.murraystate.edu.

TEACHING TIPS 193

You might also like

- Stages of Reading DevelopmentDocument12 pagesStages of Reading Developmentapi-259640817100% (1)

- Examples of Consonant BlendsDocument5 pagesExamples of Consonant BlendsNim Abd MNo ratings yet

- Phonemic AwarenessDocument10 pagesPhonemic Awarenessapi-345807204No ratings yet

- Best Start Parents Reading WorkshopDocument25 pagesBest Start Parents Reading WorkshopMeirianiMeiNo ratings yet

- Rti PyramidDocument15 pagesRti Pyramidapi-466383259No ratings yet

- Phonics: The Role Reading InstructionDocument7 pagesPhonics: The Role Reading Instructionvijeyeshwar0% (1)

- Teaching Sight WordsDocument4 pagesTeaching Sight Wordsapi-399272588No ratings yet

- Phonics WhatweknowDocument23 pagesPhonics Whatweknowoanadragan100% (1)

- What Every Educator and Parent Should Know About Reading InstructionDocument7 pagesWhat Every Educator and Parent Should Know About Reading InstructionWilliam WangNo ratings yet

- The Roots of Reading: Insights and Speech Acquisition and ReadingFrom EverandThe Roots of Reading: Insights and Speech Acquisition and ReadingRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Blending WordsDocument3 pagesBlending Wordsfernando yanesNo ratings yet

- Module 3 - Article Review - Structured Literacy and Typical Literacy PracticesDocument3 pagesModule 3 - Article Review - Structured Literacy and Typical Literacy Practicesapi-530797247No ratings yet

- Phonemic AwarenessDocument8 pagesPhonemic AwarenessAli FaizanNo ratings yet

- Identifying Persuasion ElementsDocument4 pagesIdentifying Persuasion Elementsleahjones73100% (1)

- Phonemic Awareness Lesson PlanDocument5 pagesPhonemic Awareness Lesson Planapi-571377710No ratings yet

- Math 9 - Curriculum Map - 2021-2022 - 2Document4 pagesMath 9 - Curriculum Map - 2021-2022 - 2Hassel Abayon100% (1)

- Philosophy DLL Week 2Document2 pagesPhilosophy DLL Week 2Totep Reyes77% (13)

- Share Copy - High Frequency Words vs. Sight WordsDocument15 pagesShare Copy - High Frequency Words vs. Sight WordsPhạm Bích HồngNo ratings yet

- Tier 2 Lesson Plan - U5w3Document4 pagesTier 2 Lesson Plan - U5w3api-445935606No ratings yet

- PACT Comprehension Circuit Training-Student Text Level 1 Student BookDocument192 pagesPACT Comprehension Circuit Training-Student Text Level 1 Student BookNicole SchabenNo ratings yet

- Top 10 Synthesis ECI 540 Carolina MusawwirDocument10 pagesTop 10 Synthesis ECI 540 Carolina Musawwirapi-400078361100% (1)

- Tip Sheet: Phonological Awareness Lessons & Read-Aloud BooksDocument4 pagesTip Sheet: Phonological Awareness Lessons & Read-Aloud BooksABTNNo ratings yet

- C G DET HandbookDocument51 pagesC G DET HandbookRichard MortimerNo ratings yet

- Michelle Reyes Ilp TLP 2Document6 pagesMichelle Reyes Ilp TLP 2api-528731871No ratings yet

- Reading Diagnosis ModuleDocument26 pagesReading Diagnosis ModuleProbinsyana KoNo ratings yet

- Making Words Lesson For EmergentDocument2 pagesMaking Words Lesson For Emergentapi-361979540No ratings yet

- Content Area Lesson PlanDocument10 pagesContent Area Lesson Planapi-583719242No ratings yet

- Readin G Skills: 1. Styles of ReadingDocument16 pagesReadin G Skills: 1. Styles of ReadingnenyaixpertNo ratings yet

- Lesson1 NotetakinginprintDocument6 pagesLesson1 Notetakinginprintapi-300099149No ratings yet

- Adjectives ExplainedDocument14 pagesAdjectives ExplainedNurian Xiomara PardoNo ratings yet

- Visualisation Reading Comprehension StrategiesDocument30 pagesVisualisation Reading Comprehension StrategiesANGELICA MABANANNo ratings yet

- 10 Fabulous Ways To Teach New WordsDocument3 pages10 Fabulous Ways To Teach New WordskangsulimanNo ratings yet

- Subject English Language Arts Grade 10-2 Topic/Theme Poetry & Short Stories Length (Days) 28Document28 pagesSubject English Language Arts Grade 10-2 Topic/Theme Poetry & Short Stories Length (Days) 28api-340960709No ratings yet

- DLL G6 Q4 Week 1 All SubjectsDocument37 pagesDLL G6 Q4 Week 1 All SubjectsNota BelzNo ratings yet

- SBM Assessment ToolDocument14 pagesSBM Assessment ToolMaria Angeline Delos SantosNo ratings yet

- Shared Reading Lesson Plan FormatDocument13 pagesShared Reading Lesson Plan Formatapi-296389786No ratings yet

- Ofsted Inspection Report - Niton Primary SchoolDocument10 pagesOfsted Inspection Report - Niton Primary SchoolIWCPOnlineNo ratings yet

- Phonics As InstructionDocument3 pagesPhonics As InstructionDanellia Gudgurl DinnallNo ratings yet

- CRITICAL APPRAISAL OF PHILOSOPHY - MineDocument25 pagesCRITICAL APPRAISAL OF PHILOSOPHY - MineJaini Shah57% (7)

- Classroom Observation SheetDocument2 pagesClassroom Observation SheetKian Alquilos80% (5)

- Learning Map Stage 1Document6 pagesLearning Map Stage 1api-281102403No ratings yet

- Definition of Shared ReadingDocument2 pagesDefinition of Shared ReadinghidayahNo ratings yet

- Year 1 English Plan CharthouseDocument6 pagesYear 1 English Plan CharthouseDalilah AliahNo ratings yet

- Identification and Management of Children With Specific Learning DisabilityDocument16 pagesIdentification and Management of Children With Specific Learning DisabilitySarin DominicNo ratings yet

- Interactive Read Aloud Lesson Plan 2Document3 pagesInteractive Read Aloud Lesson Plan 2api-250964222No ratings yet

- Detosil Reading DrillsDocument86 pagesDetosil Reading Drillsckabadier100% (1)

- Lesson Plan 3 Modified fs1Document1 pageLesson Plan 3 Modified fs1api-212740470No ratings yet

- The Effects of Using Litearcy Centers in A First Grade Classroom - Laquita CovingtonDocument14 pagesThe Effects of Using Litearcy Centers in A First Grade Classroom - Laquita Covingtonapi-457149143No ratings yet

- Lesson Plan GuideDocument3 pagesLesson Plan Guideapi-519215375No ratings yet

- A Good Read Literacy Strategies With NewspapersDocument55 pagesA Good Read Literacy Strategies With Newspapersapi-302151325No ratings yet

- Phonics LessonDocument3 pagesPhonics Lessonapi-248067887No ratings yet

- The Mitten - Communicating and Listening-Lesson 1Document10 pagesThe Mitten - Communicating and Listening-Lesson 1api-273142130No ratings yet

- Phonological AwarenessDocument11 pagesPhonological AwarenessJoy Lumamba TabiosNo ratings yet

- Making Predictions Lesson PlanDocument3 pagesMaking Predictions Lesson Planapi-535419905No ratings yet

- Megans Goals - Spring 2018Document3 pagesMegans Goals - Spring 2018api-321908127No ratings yet

- Miscue Analysis/ Running RecordDocument4 pagesMiscue Analysis/ Running RecordSarah LombardiNo ratings yet

- Onset RimeDocument1 pageOnset Rimeapi-217065852No ratings yet

- Running Records On VactionDocument1 pageRunning Records On Vactionapi-4577340580% (1)

- Ced 211 Paper1EffectiveTeachingDocument11 pagesCed 211 Paper1EffectiveTeachingArgee AlborNo ratings yet

- Chapter 8 Tompkins QuestionsDocument2 pagesChapter 8 Tompkins Questionsapi-393055116No ratings yet

- Ral 221 Rev Lesson Plan Template Interactive Read Aloud 1Document4 pagesRal 221 Rev Lesson Plan Template Interactive Read Aloud 1api-524241370No ratings yet

- English FPDDocument8 pagesEnglish FPDapi-306743539No ratings yet

- Observation 2 Phonics LessonDocument5 pagesObservation 2 Phonics Lessonapi-340839569No ratings yet

- Measurement Unit Plan 2020Document6 pagesMeasurement Unit Plan 2020api-511865974No ratings yet

- MST Primary Integrated6 UnitDocument25 pagesMST Primary Integrated6 Unitapi-248229122No ratings yet

- SQPL - Student Questions For Purposeful LearningDocument2 pagesSQPL - Student Questions For Purposeful Learningvrburton100% (1)

- Integers EvidenceDocument3 pagesIntegers EvidenceroylepayneNo ratings yet

- Middle School Book ListDocument6 pagesMiddle School Book ListroylepayneNo ratings yet

- FractionsDocument10 pagesFractionsroylepayneNo ratings yet

- Order of OperationsDocument11 pagesOrder of OperationsroylepayneNo ratings yet

- ABC Note TakingDocument1 pageABC Note TakingroylepayneNo ratings yet

- Fact OpinionDocument1 pageFact OpinionroylepayneNo ratings yet

- First DayDocument23 pagesFirst DayroylepayneNo ratings yet

- IntegersDocument16 pagesIntegersroylepayneNo ratings yet

- Classroom "To Be" Rules: - To Be Prepared - To Be Respectful - To Be Helpful - To Be ProudDocument17 pagesClassroom "To Be" Rules: - To Be Prepared - To Be Respectful - To Be Helpful - To Be ProudroylepayneNo ratings yet

- Moving Beyond The Page in Content Area Literacy: Comprehension Instruction For Multimodal Texts in ScienceDocument5 pagesMoving Beyond The Page in Content Area Literacy: Comprehension Instruction For Multimodal Texts in ScienceroylepayneNo ratings yet

- Math AnxietyDocument14 pagesMath Anxietyroylepayne100% (1)

- Position StatementDocument13 pagesPosition StatementroylepayneNo ratings yet

- First DayDocument23 pagesFirst DayroylepayneNo ratings yet

- Creative Writing in Math ClassroomDocument9 pagesCreative Writing in Math Classroomapi-259179075No ratings yet

- SHADES of Meaning-1Document1 pageSHADES of Meaning-1roylepayneNo ratings yet

- Self Selected ReadingDocument5 pagesSelf Selected ReadingroylepayneNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6 NotesDocument4 pagesChapter 6 NotesroylepayneNo ratings yet

- Literacy Project Rubric/Content Literacy EDUC 343 Cara Hedger, Megan Jones, and Micah BergenDocument20 pagesLiteracy Project Rubric/Content Literacy EDUC 343 Cara Hedger, Megan Jones, and Micah BergenroylepayneNo ratings yet

- The ItuDocument4 pagesThe IturoylepayneNo ratings yet

- Math BooksDocument5 pagesMath BooksroylepayneNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10Document4 pagesChapter 10roylepayneNo ratings yet

- From Efficient Decoders To Strategic ReadersDocument7 pagesFrom Efficient Decoders To Strategic ReadersroylepayneNo ratings yet

- Chapter 9 NotesDocument2 pagesChapter 9 NotesroylepayneNo ratings yet

- TrianglesDocument26 pagesTrianglesroylepayneNo ratings yet

- Literacy ProjectDocument19 pagesLiteracy ProjectroylepayneNo ratings yet

- History of Modern MathematicsDocument75 pagesHistory of Modern MathematicsgugizzleNo ratings yet

- DRProject RubricDocument1 pageDRProject RubricroylepayneNo ratings yet

- My WorksheetDocument2 pagesMy WorksheetroylepayneNo ratings yet

- Literature Focus UnitDocument8 pagesLiterature Focus Unitroylepayne100% (2)

- Megan Jones: Middle School MathematicsDocument37 pagesMegan Jones: Middle School MathematicsroylepayneNo ratings yet

- L Theory L ObjectsDocument15 pagesL Theory L Objectsapi-298340724No ratings yet

- Ede 202Document28 pagesEde 202Teacher RickyNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan AssignmentDocument4 pagesLesson Plan Assignmentapi-399254235No ratings yet

- HUMSS_CreativeNonfiction_Q4_Mod6_W34_PeerCritiqueDocument23 pagesHUMSS_CreativeNonfiction_Q4_Mod6_W34_PeerCritiqueRhaziela Eunika MalabagNo ratings yet

- San Francisco District, Pagadian City Tel. No. 215 - 3307 1 Semester SY: 2019-2020Document8 pagesSan Francisco District, Pagadian City Tel. No. 215 - 3307 1 Semester SY: 2019-2020Kaye Jean VillaNo ratings yet

- Siddiq Resume 2023MEDocument1 pageSiddiq Resume 2023MEShrenik BoraNo ratings yet

- About My School PresentationDocument6 pagesAbout My School PresentationUsharani KCNo ratings yet

- PTS Pre-Assessment ToolsDocument11 pagesPTS Pre-Assessment Toolsgracey oarNo ratings yet

- Pearl MullaDocument10 pagesPearl MullaBODDU SWAPNA 2138123No ratings yet

- Graduate School BrochureDocument2 pagesGraduate School BrochureSuraj TaleleNo ratings yet

- Leadership and Coaching Styles QuestionnaireDocument2 pagesLeadership and Coaching Styles QuestionnaireLeocel AlensiagaNo ratings yet

- Teacher Experience and Student AchievementDocument26 pagesTeacher Experience and Student AchievementAli HassanNo ratings yet

- Classcode - Familyname - Firstname - Midterms: Red ItalicsDocument4 pagesClasscode - Familyname - Firstname - Midterms: Red ItalicsChaermalyn Bao-idangNo ratings yet

- Geometry Mastery Grading Syllabus 2019-2020Document2 pagesGeometry Mastery Grading Syllabus 2019-2020api-468430151No ratings yet

- Impacting AI in Health-Care ApplicationsDocument30 pagesImpacting AI in Health-Care ApplicationsSatu AdhaNo ratings yet

- 131 FullDocument11 pages131 Fullcrys_by666No ratings yet

- Accomplishment Report On OBE 2023Document2 pagesAccomplishment Report On OBE 2023Cel Banta Barcia - PolleroNo ratings yet

- DSKP For Year 4 Listen Speak TutorialDocument6 pagesDSKP For Year 4 Listen Speak TutorialSree JothiNo ratings yet

- DLL HOPE 4 2k19Document39 pagesDLL HOPE 4 2k19Michael Franc FresnozaNo ratings yet

- Bicol University Gubat Campus: "Policies and Issues On The Internet and Implication To Teaching and Learning"Document2 pagesBicol University Gubat Campus: "Policies and Issues On The Internet and Implication To Teaching and Learning"Gerald Dio LasalaNo ratings yet

- Project AssesmentDocument32 pagesProject Assesmentapi-438800861No ratings yet

- STPR On Human ResouresDocument101 pagesSTPR On Human ResouresRahul YadavNo ratings yet

- Science Form 1 Yearly Lesson PlanDocument21 pagesScience Form 1 Yearly Lesson PlanAbdul Rahman NarawiNo ratings yet