Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Synopsis of Pamuk

Uploaded by

Zainul MujahidOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Synopsis of Pamuk

Uploaded by

Zainul MujahidCopyright:

Available Formats

SYNOPSIS & ANALYSIS OF ORHAN PAMUK’S SNOW

By:

Zainul Mujahid & Supeno

A. Synopsis

Following years of lonely political exile in Western Europe, Ka, a middle-aged

poet, returns to Istanbul to attend his mother's funeral. Only partly recognizing this

place of his cultured, middle-class youth, he is even more disoriented by news of

strange events in the wider country: a wave of suicides among girls forbidden to wear

their head scarves at school. An apparent thaw of his writer's curiosity leads him to

Kars, a far-off town near the Russian border and the epicentre of the suicides.

No sooner has he arrived, however, than we discover that Ka's motivations are

not purely journalistic; for in Kars, once a province of Ottoman and then Russian

glory, now a cultural gray-zone of poverty and paralysis, there is also Ipek, a radiant

friend of Ka's youth, lately divorced, whom he has never forgotten. As a snowstorm,

the fiercest in memory, descends on the town and seals it off from the modern,

westernized world that has always been Ka's frame of reference, he finds himself

drawn in unexpected directions: not only headlong toward the unknowable Ipek and

the desperate hope for love–or at least a wife–that she embodies, but also into the

maelstrom of a military coup staged to restrain the local Islamist radicals, and even

toward God, whose existence Ka has never before allowed himself to contemplate. In

this surreal confluence of emotion and spectacle, Ka begins to tap his dormant

creative powers, producing poem after poem in untimely, irresistible bursts of

inspiration. But not until the snows have melted and the political violence has run its

bloody course will Ka discover the fate of his bid to seize a last chance for happiness.

Ka reunites with a woman named İpek, whom he once had feelings for, whose

father runs the hotel he is staying in. İpek is divorced from Muhtar, partly due to

Muhtar's newfound interest in political Islam. In a café, the pair witness a shooting of

the local director of the Institute of Education by a Muslim extremist from out of town

who blames the director for the death of a young woman named Teslime, claiming she

Zainul Mujahid & Supeno, 2010 1

killed herself because of the director's ban on head-scarves in school. After the

incident, Ka visits Muhtar, who tells him about his experience of finding Islam, which

relates to a blizzard and meeting a charismatic sheikh named Saadettin Efendi. The

police pick up Ka and Muhtar due to the killing of the minister. Ka is questioned and

Muhtar is beaten.

Though he has suffered from writer's block for a number of years, Ka

suddenly feels inspired and composes a poem called "Snow", which describes a

mystic experience. Other poems follow. At İpek's suggestion, Ka goes to see Sheikh

Saadettin and confesses that he associates religion with a backwardness that he does

not want himself or Turkey to fall into. But he feels a sense of comfort with the

Sheikh and begins to accept his new poems as gifts from God.

Other significant characters Ka encounters include a wanted Muslim radical

named Blue and İpek's younger sister Kadife, who has joined and become the leader

of the "head-scarf girls", those who insist upon being "covered." Through Kadife, he

meets another head-scarf girl, Hande, who suggested suicide to Teslime but insists she

did not intend for the girl to follow through. Throughout the book, the act of insisting

upon wearing a head-scarf, which places these girls in a head-on collision with the

state authorities and entails enormous pressures and sacrifices, is described as an act

of empowerment and assertion of their identity as women; in one passage, Ka refers to

them as "Islamic Feminists".

Ka is impressed by Necip, a student at the religious high school, who, like

many of the young Muslims at the school, is quite taken by Kadife. The narrator lets

the reader know that Necip will die soon. Growing tensions between secularists and

Islamists explode during a televised event at the National Theater, during which one

secular group puts on a classic play condemning head scarves. When Muslims protest,

three nationalists take the stage and start firing. Necip is among those killed. The

police and military establish martial law, and Ka is taken in for questioning because

he has been seen with Islamists. He is shattered to find Necip's body in the morgue

and identifies him as the one who led him to Blue.

Ka is taken to meet Sunay Zaim, an actor whose group put on the play at the

National Theater and who is now orchestrating the round-ups and investigations of

suspicious persons. Sunay is a staunch Turkish Republican, who had often played

Zainul Mujahid & Supeno, 2010 2

with great conviction revolutionaries and dictators such as Robespierre, Napoleon and

Lenin, but whose dream to play Attaturk, the founder of the Turkish Republic, was

frustrated. As the snow has made the roads and railroads impassable, no outside

authorities are able to intervene in the coup. The isolation of Kars and Sunay's old

friendship with the senior military officer left in charge of the local garrison enabled

him to become a revolotionary dictator in real life as well as on the stage, for at least a

few days - his act being simultaneously a coup d’etat and a coup de theatre.

Ka is then taken by Kadife to speak with Blue, who is Kadife's lover. Ka

convinces Blue that he has a contact at a newspaper in Germany who will be willing

to print a statement denouncing the coup if Blue can get support from non-Islamists.

To further this fiction, Ka returns to his hotel to convince Kadife and Ipek's leftist

father Turgut Bey to collaborate on the statement. After the father and Kadife leave,

Ka's longing for İpek is fulfilled when the two make love.

Turgut Bey attends a meeting at which representatives from the various

factions opposed to the coup, including Islamists, leftists, and Kurds, attempt

comically to produce a coherent statement to the European press denouncing the

action. After Blue is arrested and held by the nationalists, Ka negotiates a deal with

Sunay Zaim that will result in Blue's release but only if Kadife agrees to play a role in

Zaim's production of Thomas Kys’s and The Spanish Tragedy and remove her head-

scarf on live television during the course of the play. Both Kadife and Blue agree.

Ka is soon picked up and beaten by two policemen who are trying to keep tabs

on Blue. He is also given the devastating news that Ipek was Blue's mistress during

her marriage to Muhtar and still keeps in contact with him. Ipek confesses the affair

and further indicates that Kadife only got involved with Blue out of envy. Ka's

jealousy is intense and the two fall asleep after weeping together. She still believes

that they can go to Frankfurt and be happy, and he eventually comes around to

believing it again too. However, before they can leave he must convince Kadife to not

take her head-scarf off during the play as both Ipek and Turgut Bey have become very

concerned at the possible reaction of the students from the religious school. Despite

Ka's urging, Kadife insists upon uncovering herself during the performance.

After a scene in which Ka is seen confused and tormented by feelings of pain

and jealousy, the narrative describing events from his point of view abruptly breaks

Zainul Mujahid & Supeno, 2010 3

off. The narrator explains that Ka had left behind a detailed account of his acts and

feelings while in Kars, but that there was no reference to his last hours in the city, and

it is left to his friend Orhan to try to reconstruct these by following in Ka's footsteps,

visiting the places where he had been and meeting the people he had met.

Ka's actions immediately after leaving the theater remain a mystery which is

never completely untangled. Orhan is, however, able to establish that Ka was later

taken by the military to the train station, where he was put on the first train scheduled

to leave now that the routes from the town are open again. Ka complied but sent

soldiers to retrieve İpek for him. However, just as İpek is saying her farewells to her

father, news arrives that Blue and Hande have been shot. İpek is shattered and blames

Ka for leading the police to Blue's hideout. Instead of going to Ka, she and her father

go to the theater to see Kadife.

The novel's narrator then describes events at the theater as if he has

reconstructed them from various sources. Kadife and Zaim have an on-stage

discussion about suicide and the different reasons why men and women kill

themselves. A garret and noose are set up, and Zaim hands Kadife a gun after he

demonstrates that it is not loaded. When Kadife shoots Zaim much of the audience

assumes his death is staged, and even Kadife appears to be surprised that the gun is in

fact loaded. Zaim had clearly prepared and orchestrated his own death on stage,

"pushing art to its farthest limits" and preferring to die at the peak of his theatrical and

political career. Soon afterwords, as the snow has subsided, Ka's train departs and

local authorities enter the town to stifle the coup and restore order.

Years later, the narrator goes to Kars to uncover details on Ka's story. He

meets with many of the principals, including Kadife, who served very little time for

what was ruled an accidental homicide and is now married to a student from the

religious school. Meeting Ipek, the narrator himself falls deeply in love with her and

becomes intensely jealous of his dead friend (and of the dead Blue). In his talk with

İpek he tells her that Ka was a shattered man who never forgot about İpek but was

prevented from returning to Kars due to a warrant for his arrest. İpek is still convinced

that Ka betrayed Blue. Indeed, the narrator soon finds evidence that suggests that Ka

went back to talk to the police after his visit to the theater and probably told them

Zainul Mujahid & Supeno, 2010 4

where to find Blue. İpek has remained unmarried, does not expect to ever find love

again, and devotes herself to her nephew.

In the end it is disclosed that a new group of Islamic militants was formed by

younger followers of Blue who had been forced into exile in Germany and based

themselves in Berlin, vowing to take revenge for the death of their admired leader. It

is assumed that one of them had assassinated Ka and taken away the only extant copy

of the poems he had written in Kars. Thus, while much is told about the names of

these poems, their themes and the circumstances under which each was written, the

poems themselves are lost.

B. Analysis

After reading Pamuk’s Snow thoroughly, we catch that the author alertly

mixes various events that make the story alive and of course unique. It is alive since

the scene is full of critical dialogues that make us as the readers as if got involved in

it. Meanwhile, the uniqueness can be obviously seen through the changing topic of

dialogues, such as Islam (fundamentalism), secularism, God, love, and art. Pamuk is

to us very smart in organizing the serious dialogues into mischievous wit by

empowering irony where according to Sisk and Sanders (1972: 228):

Bitter irony uses the same devices as satire – sarcasm, invective,

understatement or exaggeration, mockery, ridicule, paradox. … expresses

human frailties and evil by methods that emphasize the reversal or topsy-turpy

differences between aspiration and reality, aim and fulfillment, self-portrait

and mirror image.

An amazing flow of dialogues on Islamic teachings, secularity, sincerity,

conscience, and the like between the young fundamentalist boy - Vahit Suzme - and

Professor Nuri Yilmaz - the director of the Institute of Education - make us conscious

that the sate policy, in this case Turkey (Ankara), is very powerful and must be

followed by all provinces including Kars where the story takes place. The Professor

whose religion is Islam is illustrated by Orhan Pamuk as having no strong principle.

He tends to follow secular mainstream by banning and barring headscarf girls from

schools as well as classrooms “We live in a secular state. It’s the secular state that has

banned covered girls, from schools as well as classrooms” (Pamuk, 43), eventhough

he has a good understanding on the Holy Kuran verses, for example when he

Zainul Mujahid & Supeno, 2010 5

pronounces the translation/content of the Thirty-First Verse. The debates between

both the young boy who takes two days on snow and stormy roads from Tokat to Kars

and the Professor are getting ‘hotter’ eventhough some of the conversations run

smoothly and slowly but irritating or might be said as attacking.

The Professor’s answers to Vahit Suzme’s questions never bring satisfaction

for the Professor frequently launches irrational arguments, such as when Suzme asks

“Ezcuse me, sir. May I ask you a question? Can a law imposed by the state cancel out

God’s law?”, the Professor answers “That’s very good question. But in secular state

these matters are separate” (Pamuk, 43). More questions are asked by the young boy

but no satisfying answers “ … Does the word secular mean godless”, “What’s more

important, a decree from Ankara or a decree from God?” (Pamuk, 44). During the

dialogues ironies are played nicely by Pamuk where eventhough the young boy really

hates the Professor, he mockingly kisses the Professor’s hand by saying: “That’s

another good straight answer, sir. May I kiss your hand? Please, sir, don’t be afraid.

Give me your hand. Give me your hand and watch how lovingly I kiss it. Oh, God be

praised. Thank you. Now you know how much respect I have for you. May I ask you

another question, sir?” (Pamuk, 43); “That’s an excellent answer, sir. Allow me to

kiss your hand. But how can you equate the hand of a thief with the honor of our

women?” These utterances are considered humorous because of the meeting of

congruity and incongruity in the dialogues of both young boy and Professor, as

theoretically stated by McGhee (1979: 6-8):

The notions of congruity and incongruity refer to the relationship between

components of an object, event, idea, social expectation, and so forth. When

the arrangement of the constituent elements of an event is incompatible with

the normal or expected pattern, the event is perceived as incongruous. The

incongruity disappears only when the pattern is seen to be meaningful or

compatible in a previously overlooked way. This discovery has long been

considered to be important for humor, in that the nonsense that results from

the perception of incongruity makes sense when we see the unexpected

meaning or “get the point”

To better understand the ideas in the novel, we make use of a New Historicist

Approach. New Historicism states that a literary text should be seen as a product of its

“time, place and circumstances of its composition rather than as an isolated creation

(Wikipedia, a) or elaborately, most fundamentally, there is an insistence that all

Zainul Mujahid & Supeno, 2010 6

systems of thought, all phenomena, all institutions, all works of art, all literary texts

must be situated within a historical perspectives. In other words, texts or phenomena

cannot be somehow torn from history and analyzed in isolation, outside the historical

process. They are determined in both their form and content by their specific

historical circumstances, their specific situation in time and place (Habib, 2005: 760)

New Historicist also argues that “text not only represent culturally constructed forms

of knowledge and authority but actually instantiate or reproduce in readers the very

practices and codes they embody” (Cadzow, 2005). Since there are several items as

mentioned above that must be situated in historical perspectives. We in this limited

discussion try to investigate the historical background and the condition of women.

1. Historical Background

The discussion of different ideas and ideologies present in Snow reflects the

political choices Turkey currently has to make as the first predominantly Muslim

country to apply for membership in the European Union. On the one hand, many

people in Turkey and Europe hope that traditional Turkish membership will force

Turkey to implement reforms that could make the country “a model of democracy for

the rest of the Middle East” (Wikipedia, b). On the other hand, several European

countries have expressed concerns about allowing predominantly Muslim country into

secular Europe. To better understand this hopes and concerns one needs to briefly

consider the long history of interaction between the East and the West.

At first, after Mohammad established Islam in the 7th century, a dramatic

expansion took place, largely at the expense of Christianity, until the Islamic

dominance ended with the collapse of the Ottoman Empire after World War I

(Wikipedia, c). By September 18, 1922 the new Turkish state was established. On

November 1, the newly founded parliament formally abolished the Sultanate, thus

ending 623 years of Ottoman rule and the Republic was officially proclaimed on

October 29th, 1923 in the new capital of Ankara (Wikipedia, b).

Mustafa Kemal became the republic’s first President of Turkey and

subsequently introduced many radical reforms with the aim of founding a new secular

republic from the remnants of its Ottoman past. According to the Law on Family

Zainul Mujahid & Supeno, 2010 7

Names, the Turkish parliament presented Mustafa Kemal with the honorific name

“Ataturk” (Father of the Turks) in 1934.

Snow is set mainly in the city Kars in the northeast of Turkey. According to

Wikipedia, it belonged to an Armenian Kingdom in the 10th century, and was later

captured by Turks, Mongols and by Timur. It then came under Ottoman rule until

1878, when it was transferred to the Russians. After the subjugation to Russia, many

Muslims emigrated to Turkey, but at the same time many Greeks, Armenian and

Russians migrated to the city. In the 1918 the Turks took back control for a year until

Armenia with the support of British troops took it back in 1919. In 1920, Kars was

again ceded to Turkey. The government of Armenia does not to this day recognize the

current border (Wikipedia, d). Traces of Kars turbulent past are also present in the

novel, especially in the description of different houses (Pamuk, 7, 164).

Turkey is a secular state with no official state religion. The Turkish

constitution provides for freedom of religion and conscience. The role of religion has

been controversial debate over the years since the formation of Islamist parties.

Turkey was founded upon a strict secular constitution which forbids the influence of

any religion, including Islam. There are sensitive issues, such as the fact that the

wearing of Hijab is banned in universities and public or government buildings as

some view it as a symbol of Islam – though there have been efforts to lift the ban

(Wikipedia, d).

In Pamuk’s Snow, it is clearly described that the notions of modernity and

secularization (westernization) are in line with the aim and efforts of the Turkish

authority to make radical reform by avoiding religious symbols. It can be seen

through: “ … The culture of the Russians brought to Kars now fit perfectly with the

Republic’s westernizing project” … “Kars would dance the latest dances as pianos,

accordions, and clarinets were played in the open air. In the summer time, girls could

wear short-sleeved dresses and ride bicycles through the city without being bothered”

(Pamuk, 22). Meanwhile, on the other side, underestimation to head scarf girls

happens. To the westernized upper-middle class circles of the young Ka’s Istambul, “

… a covered women would have been someone who had come in from the suburbs –

from the Kartal vineyards, say – to sell grapes. Or she might be the milkman’s wife or

someone else from the lower classes” (Pamuk, 35).

Zainul Mujahid & Supeno, 2010 8

Snow exposes the social and historical atmosphere in Turkey, especially Kars.

The understanding of historical perspectives before or after reading the novel will

make us comprehend the content. Therefore, according Habib (2005: 760) “literature

must be read within the brother context of its culture, in the context of other

discourses ranging over politics, religion, and aesthetics, as well as its economic

context.”

2. The Condition of the Women

As shown, religious fundamentalism, whether democratically elected or not,

does not look attractive if one is concerned about the situation for out-groups like

women. Oppression of women is evident through out Snow. Already in the beginning

of the novel we are informed that one of the reasons why Ka travels to Kars, is the

epidemic of suicides among young Muslim women (Pamuk, 8). During Ka’s

investigations into the suicides he learns that they all happen quite abruptly,

something that disturbs him more than hearing about the “constant beatings to which

the girls were subjected, or the insensitivity of fathers who wouldn’t even let them go

outside, or the constant surveillance of jealous husbands” (Pamuk, 14). However,

although the hardships the girls had to endure contributed to their decisions to commit

suicide, they alone can not explain the sudden epidemic. That is to say, as the deputy

governor points out to Ka, that if the sole reason was that the girls were unhappy, then

“half the women will be killing themselves” (Pamuk, 17).

According to Amnesty international the deputy governor might be right in his

estimate that half the women in Turkey have reasons to consider suicide. In a report

published by Amnesty International in 2004, Amnesty states that women in Turkey

are discriminated in every area of life. Moreover, the report claims that over half of

the women in Turkey were married without their consent. The report also presents

many documented cases of women “who are beaten, raped, and in some cases even

killed or forced to commit suicide” (Amenesty, 2004).

Yet the oppression suffered by women in a patriarchal society is, as stated, not

seen as the main reason for the girls’ suicides. Instead the idea that suicide might

spread contagiously has taken hold (Pamuk, 15). The man who murders the Director

of the Institute of Education also suggests that at least one of the girls committed

Zainul Mujahid & Supeno, 2010 9

suicide for mainly religious reasons (Pamuk, 42 - 52). Before the director is murdered,

the director offers a more prosaic explanation for the girl’s suicide; she had had an

affair with a policeman, and she killed herself when she learned that the policemen

was married (Pamuk, 46).

Interestingly, another of the head scarf girls, Hande, also explains that she

does not want to remove her head scarf out of the fear of becoming a woman that

“can’t stop thinking about sex” (Pamuk, 132). The executioner of the Director

mentioned earlier, seems to agree with her. If Turkey continues to push the Turkish

women in Europe degraded in the wake of the sexual revolution (Pamuk, 45), he asks,

and also wanders if that would not turn Turkish men into pimps. Obviously,

headscarves have a lot to do with suppressing women’s sexuality, either to protect

them from degradation, as the executor suggests, or, to protect men’s honor in

cultures where preservation of honor refers to “maintenance of virginity of unattached

women and to the exclusive monogamy of the remainder” (Wkipedia, b). At closer

examination, some of the suicides in Snow indeed also seem connected to failures at

maintenance of virginity or forced marriages (Pamuk, 13, 15, 46).

As shown above, many reasons are given as to why the girls commit suicide,

most of them pointing to patriarchal oppression legitimized by religion, but there is

little expansion for why they willingly choose to wear what some, as for instance the

actress Funda Eser, clearly see as the symbol of this oppression. Funda Eser tells the

audience during the first play that the “scarf, the fez, the turban and the headdress

were symbols of the reactionary darkness in our souls” (Pamuk, 151 – 152). Since the

percentage of women wearing headscarves has dropped from 16 to 11 percent in

Turkey, according to an article in Newsweek, perhaps more and more women agree

with Funda’s interpretation (Matthews, 2006).

Head scarves play an important role in the two plays that Funda’s husband

Sunay stages, but they are not included in the statement about the events that different

characters co-write. When Blue first suggests to write the statement, his lover Kadife

reflects that there will not be any mention in the statement of the head scarf girls and

their struggle. Kadife says that she pities “these men wasting so much effort to gain

exposure themselves while we endure so much to protect our privacy” (Pamuk, 236).

Wearing a head scarf is thus not seen by Kadife as a way to make a statement;

Zainul Mujahid & Supeno, 2010 10

consequently she does not see wearing a scarf as a way to be seen, instead of pitied,

something that is very important to the men (Pamuk, 410).

Yet, the wearing of head scarves is not a trivial matter for the girls. As

mentioned, they are willing to go against the authorities and be banned from school if

they are not allowed to wear their scarves. According to Muslim researcher Rachel

Woodlock “ the ability to choose whether to veil or not, in accordance with the

Muslim feminist’s own personal interpretation of Islamic faith and morality, is the

very heart of what Islam represents to Muslim feminists: the basic Qur’anic ethic of

the sovereign right of both women and men as human beings who have the freedom

of self-determination” (Woodlock, 2007). If Woodlock is right, the girls in Snow

perhaps choose to wear the scarves as a symbol of self-determination.

Interestingly, an explanation for the suicides similar to Woodlock’s

explanation about veils is given by Hande. She says that girls commit suicide as a way

to control their own bodies, and explain that control is “what suicide offers girls

who’ve been duped into giving up their virginity, and it’s the same for virgins who are

married off to men they don’t want” (Pamuk, 124), implying that it is a question about

self-determination. That is to say, that in their oppressed situation the only possibility

to some measure to control about what will happen to one’s body is to commit

suicide.

Yet to escape their oppressed situation, they could simply steal some money

and leave, as Kadife points out (Pamuk, 397). Kadife therefore gives what she thinks

is the real reason: “women commit suicide to save their pride” (Pamuk, 397). Just as

the men decide to despise anything Western to avoid having to ‘grovel’ (Pamuk, 350),

women perhaps accept oppression rather than loose their pride by imitating Western

emancipation. When the oppression becomes unbearable, they commit suicide.

References:

a. Book

Habib, M.A.R. 2005. A History of Literary Criticism: From Plato to the Present.

Malden, USA: Blackwell Publishing.

McGhee, Paul E. 1979. Humor: Its Origin and Development. Sanfransisco: W.H.

Freeman and Company.

Zainul Mujahid & Supeno, 2010 11

Sisk, Jean and Jean Saunders. 1972. Composing Humor, Twain, Thurber, and You.

New York: Harcourt Brace Javanovich, Inc.

Pamuk, Orhan. 2005. Snow. New York: Vintage International.

b. Internet sources

Amnesty International. ‘Turkey: Women Confronting Family Violence Summary’.

2004.

http://web.amnesty.org/library/index/engEUR440232004?open&of=eng-tur.

Accessed on 9 December 2010

Cadzow, Hunter. New Historicism (2nd ed, 2005)

http://litguide.press.jhu.edu/cgibin/view.cgi?eid=194&query=new%20historicism

Accessed on 9 December 2010

Matthews, Owen. ‘Mission Impossible?’ Newsweek, 2006.

www.msnbc.msn.com/id/15938227/site/newsweek/page/2/

Accessed on 11 December 2010

Wikipedia, a . http:/en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_historicism.

Accessed on 10 December 2010

Wikipedia, b . http:/en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Accession_of_Turkey_to_the_

European_Union

Accessed on 9 December 2010

Wikipedia, c. http://en.wikipedia.org/wik/Ottoman_empire.

Accessed on 9 December 2010

Wikipedia, d. http://en.wikipedia.org/wik/Kars. Accessed on 9 December 2010

Woodlock, Rachel. ‘Muslim Feminists and the Veil: To Veil or not to Veil – is the

Question?’

www.islamfortoday.com/feminists_veil.htm. Accessed on 15 Januray 2007

Zainul Mujahid & Supeno, 2010 12

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Baltimore City Fiscal Year 2024 Preliminary BudgetDocument190 pagesBaltimore City Fiscal Year 2024 Preliminary BudgetChris BerinatoNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Dr. Thein Lwin Language Article (English) 15thoct11Document17 pagesDr. Thein Lwin Language Article (English) 15thoct11Bayu Smada50% (2)

- David Lloyd - Settler Colonialism and The State of ExceptionDocument22 pagesDavid Lloyd - Settler Colonialism and The State of ExceptionAfthab EllathNo ratings yet

- Fascism in ItalyDocument14 pagesFascism in ItalyFlavia Andreea SavinNo ratings yet

- Agrarian ReformDocument36 pagesAgrarian ReformSarah Buhulon83% (6)

- Lokin v. ComelecDocument4 pagesLokin v. ComelecKreezelNo ratings yet

- Legaspi Vs CSCDocument2 pagesLegaspi Vs CSCcyhaaangelaaa100% (1)

- Interview Summary and SynthesisDocument3 pagesInterview Summary and Synthesisselina_kollsNo ratings yet

- Constitution of PTAFOADocument15 pagesConstitution of PTAFOAS MNo ratings yet

- The International Tribunal For The Law of The Sea (ITLOS) - InnoDocument70 pagesThe International Tribunal For The Law of The Sea (ITLOS) - InnoNada AmiraNo ratings yet

- Proposal UpdatedDocument1 pageProposal UpdatedKiran KumarNo ratings yet

- Castle Rock Vs GonzalesDocument31 pagesCastle Rock Vs GonzalessabastialtxiNo ratings yet

- John Adams: Jump To Navigationjump To SearchDocument4 pagesJohn Adams: Jump To Navigationjump To SearchLali HajzeriNo ratings yet

- Sahil Group DDocument2 pagesSahil Group DAbhishek SardhanaNo ratings yet

- Midterm Exam GEC 18 EthicsDocument2 pagesMidterm Exam GEC 18 Ethicslxap2023-6821-74342No ratings yet

- Right To Work IndiaDocument5 pagesRight To Work IndiagambitsaNo ratings yet

- Proclamation: Special Observances: Caribbean-American Heritage Month (Proc. 8153)Document2 pagesProclamation: Special Observances: Caribbean-American Heritage Month (Proc. 8153)Justia.comNo ratings yet

- Campus Journalism Editorial WritingDocument2 pagesCampus Journalism Editorial WritingCharlene RiveraNo ratings yet

- Handbook of Information 2009 - 2Document68 pagesHandbook of Information 2009 - 2Shivu HcNo ratings yet

- 100 Performing Ceos and Leaders of PakistanDocument10 pages100 Performing Ceos and Leaders of PakistanMujahid HussainNo ratings yet

- 65.pimentel vs. Senate Committee of The Whole, 644 SCRA 741Document14 pages65.pimentel vs. Senate Committee of The Whole, 644 SCRA 741Vince EnageNo ratings yet

- Reiigen Bridgehead Offensive Hasty Assault River CR Leavenw - Orth Ks Comba M Oyloe Et Al 23 May 84Document86 pagesReiigen Bridgehead Offensive Hasty Assault River CR Leavenw - Orth Ks Comba M Oyloe Et Al 23 May 84Luke WangNo ratings yet

- 2016 Partition of India and PakistanDocument79 pages2016 Partition of India and PakistanPadarabinda MaharanaNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id1276962Document5 pagesSSRN Id1276962MUHAMMAD ALI RAZANo ratings yet

- Twinning Fiche - NASRI - AL 20 IPA OT 01 22 TWL - 11.10.2022-1Document30 pagesTwinning Fiche - NASRI - AL 20 IPA OT 01 22 TWL - 11.10.2022-1vaheNo ratings yet

- James Madison Republican or Democrat by Robert A DahlDocument11 pagesJames Madison Republican or Democrat by Robert A DahlcoachbrobbNo ratings yet

- Suneel Jaitley and Ors. V.state of HaryanaDocument4 pagesSuneel Jaitley and Ors. V.state of HaryanaHaovangDonglien KipgenNo ratings yet

- Project Report On GST-2018Document32 pagesProject Report On GST-2018Piyush Chauhan50% (6)

- ConstitutionDocument16 pagesConstitutionMiloyo JuniorNo ratings yet

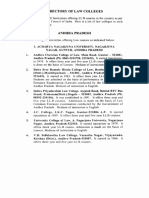

- Andhra Pradesh - Law ColleageDocument6 pagesAndhra Pradesh - Law ColleageSreenivasareddy KonduriNo ratings yet