Professional Documents

Culture Documents

NFL Essay

Uploaded by

curbedla0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

84 views6 pagesRuben navarrette: the lack of intelligent public discourse over the stadium proposals is distressing. The stadium proposal is nothing more than a generic formula, he says. Downtown Los Angeles has been searching for a new identity since the mid-1920s.

Original Description:

Original Title

nfl essay

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

DOC, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentRuben navarrette: the lack of intelligent public discourse over the stadium proposals is distressing. The stadium proposal is nothing more than a generic formula, he says. Downtown Los Angeles has been searching for a new identity since the mid-1920s.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as DOC, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

84 views6 pagesNFL Essay

Uploaded by

curbedlaRuben navarrette: the lack of intelligent public discourse over the stadium proposals is distressing. The stadium proposal is nothing more than a generic formula, he says. Downtown Los Angeles has been searching for a new identity since the mid-1920s.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as DOC, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 6

What is distressing in all of this, however, is not the

bickering but the total lack of intelligent public discourse

over the stadium proposals from the perspective of urban

planning. This is partly by design. AEG, for example, has

refused to disclose the exact location of the proposed

stadium site and has yet to complete a formal design.

Hahn has not exactly pressed the company to do so. The

assumption seems to be that all development is good

development, that anyone willing to invest large sums of

money in a decrepit downtown neighborhood should be

greeted with heads bowed in appreciation--or at least get a

supportive pat on the back.

Such an attitude toward a pro- ject that would have a

significant effect on the physical shape of downtown would

be understandable if a big development company could be

trusted to create an original, thoughtful alternative to the

kind of sports-retail-entertainment centers that are

sprouting all over America. But AEG's proposal is nothing

more than a generic formula--one unlikely to spark the kind

of urban renaissance that its planners have promised.

Downtown Los Angeles, meanwhile, has been searching

for a new identity since the mid-1920s, when its importance

as a vibrant urban center first began to fade as the city

expanded westward. Its revival will require the highest

levels of planning, and an injection of bold, new ideas.

Anything short is unlikely to turn around an area known

largely for its dilapidated buildings and empty parking lots.

The stadium proposal should be understood as part of a

much bigger plan, all of it currently controlled by AEG.

The first phase, Staples Center, was completed in 1999.

Last fall, the city approved the second phase of

development, a 40-acre retail, entertainment and housing

complex just to the north of Staples. It would include a

7,000-seat theater, a 1,200-room hotel, several blocks of

retail along Olympic and Figueroa and 800 units of

housing. (AEG has yet to set a date for groundbreaking on

this phase of development.)

The football stadium would cover roughly 20 acres just to

the east of the retail complex. And although the developer

has refused to disclose its exact location, most reports place

it between 11th and 12th streets around Hope Street. AEG

has unveiled a very preliminary stadium design by the L.A.

office of Seattle-based NBBJ Architects.

Nonetheless, the thinking behind the plan is relatively

clear-- and somewhat predictable. It embodies the kind of

"pedestrian- friendly" planning formula that has become

the norm among major developers in recent years. In a

nutshell, the idea is to create instantly the kind of vibrant

street life that exists in older, denser and more traditional

city centers. The tactics are simple enough: Replace large,

monolithic structures with a more varied, small-scaled play

of forms and build lots and lots of retail along the street.

That pattern is already visible in the design of Staples

Center, whose ground level includes offices, a restaurant

and shops, which wrap around its base from Figueroa to

11th Street and are intended to give the structure a more

human scale.

It is the development's second phase--the retail and

entertainment complex--that is meant to provide the glue

that will transform the area into a buzzing urban hub.

Anchored by a vast pedestrian plaza, which faces Staples to

the south, the complex would essentially be an open-air

mall. Surrounded by parking structures, stuffed with a mix

of chain restaurants and stores, it recalls recent

developments, such as the Grove at Farmers Market in the

Fairfax district of L.A. and Pasadena's Paseo Colorado.

Not surprisingly, AEG has vague plans to include even

more retail space along the stadium's base.

The emphasis on shops and public space has obvious

political benefits. It gives the public the impression that the

developer is concerned about the kind of quality-of-life

issues that have become a common theme in contemporary

politics. And the conventional wisdom is that such

developments are a significant improvement over the kind

of enclosed, air-conditioned malls that became the norm

only a few decades ago.

But the impact such a development would have on the

surrounding urban fabric is more dubious. Sports retail-

entertainment complexes are largely introverted, self-

contained organisms. As such, they are unlikely to spur the

kind of broad revitalization that the developers have

promised. This is especially true of the football stadium.

No amount of retail shops will disguise what it actually is:

an enormous void that, the developer admits, will remain

empty 320-plus days a year.

There are other options. The most obvious would be to

renovate the existing L.A. Coliseum, a landmark structure

at the edge of Exposition Park. One of the city's oldest

historic districts, the area was originally designed as a

series of monuments set around a formal Beaux Arts park.

It includes the 1920s-era Armory building-- currently being

transformed into a science school by the Santa Monica-

based architectural firm Morphosis--and the Natural

History Museum, which is in the midst of hiring an

architect for a major expansion.

Renovating the Coliseum stadium would not only bolster

such redevelopment efforts, it would add another element

to what is slowly becoming a more genuinely rich and

democratic public forum. It would also serve to strengthen

the identity of an existing community of mostly lower-

middle-class homes.

The more essential problem, however, is not where the

stadium should go, but how such decisions are made.

AEG's decision to build the stadium near Staples has

nothing to do with urban planning issues but with the logic

of corporate tie-ins. It is intended to guarantee that, after

paying the price of admission to a football game, visitors

could then wander out and buy a T-shirt and steak dinner at

an AEG retail mall or see a show at the AEG theater.

That experience might be slightly less disturbing if AEG's

proposal were more daring. The robber barons of an earlier

age were often driven by greed. But they were also apt to

promote bolder, more original visions. The original

"Miracle Mile," for example, which was conceived by the

realtor A.W. Ross, was an architectural response to L.A.'s

nascent car culture that was radical for its time. In New

York, Rockefeller Center was more than a money-

generating office complex; it became a symbol of

capitalism's relentless drive. Whatever the motive--a sense

of civic pride, outright vanity or fear of death--these

developers were driven to reach beyond the average and the

mundane.

Thus far, AEG's plans for downtown have yet to show such

ambition. They are safe, formulaic, somewhat soulless.

They embody an age of corporate gigantism in which

decisions are made by committee, and the only real concern

is the bottom line.

If these corporations insist on offering up tired old formulas

as the future of our cities, then it is the government's

responsibility to hold them to a higher standard. Hahn

could begin by acknowledging that effective city planning

requires more than just spending bails of money. He could

stand up to developers who try to strong-arm the city into

accepting gargantuan urban proposals even before they

have been adequately thought through.

Of course, some developers will tell the city to get lost. So

what? No development at all may be a better option than

selling off the city's soul.

You might also like

- Airbnb Arts FinalDocument16 pagesAirbnb Arts FinalcurbedlaNo ratings yet

- Ideal Properties Group - Market Report 2Q 2014Document13 pagesIdeal Properties Group - Market Report 2Q 2014curbedlaNo ratings yet

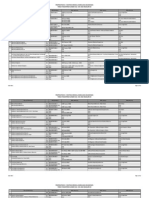

- L.A. Releases List of 134 Medical Marijuana Dispensaries Allowed To Continue OperatingDocument12 pagesL.A. Releases List of 134 Medical Marijuana Dispensaries Allowed To Continue OperatingLos Angeles Daily NewsNo ratings yet

- Expo Line Tentative RulingDocument50 pagesExpo Line Tentative RulingcurbedlaNo ratings yet

- Downtown Hotel AnalysisDocument29 pagesDowntown Hotel AnalysiscurbedlaNo ratings yet

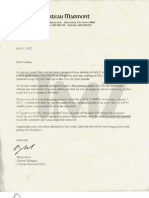

- Lindsay Lohan Chateau Marmont BillDocument15 pagesLindsay Lohan Chateau Marmont Billcurbedla100% (1)

- HCP PresentationDocument25 pagesHCP PresentationcurbedlaNo ratings yet

- Regional Connector LetterDocument12 pagesRegional Connector LettercurbedlaNo ratings yet

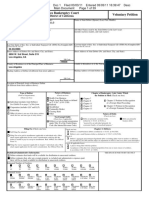

- United States Bankruptcy Court Voluntary Petition: Central District of CaliforniaDocument39 pagesUnited States Bankruptcy Court Voluntary Petition: Central District of CaliforniacurbedlaNo ratings yet

- Cha Mber of Com MerceDocument16 pagesCha Mber of Com MercecurbedlaNo ratings yet

- Zev Yaroslavsky Letter To Ron MeyerDocument2 pagesZev Yaroslavsky Letter To Ron MeyercurbedlaNo ratings yet

- SanteeDocument1 pageSanteecurbedlaNo ratings yet

- Report of The Chief Legislative Analyst: MarchDocument59 pagesReport of The Chief Legislative Analyst: MarchcurbedlaNo ratings yet

- Planning Dept NewsletterDocument4 pagesPlanning Dept NewslettercurbedlaNo ratings yet

- Senate Committee On Governance and Finance: Restructuring RedevelopmentDocument5 pagesSenate Committee On Governance and Finance: Restructuring RedevelopmentcurbedlaNo ratings yet

- ResolutionDocument2 pagesResolutioncurbedlaNo ratings yet

- Carstens 2 Chatten-Brown, Carstens, 3 4 CA 310.314.8040 FaxDocument13 pagesCarstens 2 Chatten-Brown, Carstens, 3 4 CA 310.314.8040 FaxcurbedlaNo ratings yet

- Myths and Facts About The Planning Departments Recent InitiativesDocument5 pagesMyths and Facts About The Planning Departments Recent InitiativescurbedlaNo ratings yet

- 1Document28 pages1curbedlaNo ratings yet

- Patel LetterDocument3 pagesPatel LettercurbedlaNo ratings yet

- Donald ShoupDocument2 pagesDonald Shoupcurbedla100% (1)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5784)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- SD-SCD-QF75 - Factory Audit Checklist - Rev.1 - 16 Sept.2019Document6 pagesSD-SCD-QF75 - Factory Audit Checklist - Rev.1 - 16 Sept.2019Lawrence PeNo ratings yet

- BPO UNIT - 5 Types of Securities Mode of Creating Charge Bank Guarantees Basel NormsDocument61 pagesBPO UNIT - 5 Types of Securities Mode of Creating Charge Bank Guarantees Basel NormsDishank JohriNo ratings yet

- LON-Company-ENG 07 11 16Document28 pagesLON-Company-ENG 07 11 16Zarko DramicaninNo ratings yet

- Timely characters and creatorsDocument4 pagesTimely characters and creatorsnschober3No ratings yet

- MSDS FluorouracilDocument3 pagesMSDS FluorouracilRita NascimentoNo ratings yet

- CGV 18cs67 Lab ManualDocument45 pagesCGV 18cs67 Lab ManualNagamani DNo ratings yet

- Imaging Approach in Acute Abdomen: DR - Parvathy S NairDocument44 pagesImaging Approach in Acute Abdomen: DR - Parvathy S Nairabidin9No ratings yet

- PWC Global Project Management Report SmallDocument40 pagesPWC Global Project Management Report SmallDaniel MoraNo ratings yet

- PREMIUM BINS, CARDS & STUFFDocument4 pagesPREMIUM BINS, CARDS & STUFFSubodh Ghule100% (1)

- Diemberger CV 2015Document6 pagesDiemberger CV 2015TimNo ratings yet

- ULN2001, ULN2002 ULN2003, ULN2004: DescriptionDocument21 pagesULN2001, ULN2002 ULN2003, ULN2004: Descriptionjulio montenegroNo ratings yet

- Childrens Ideas Science0Document7 pagesChildrens Ideas Science0Kurtis HarperNo ratings yet

- Amul ReportDocument48 pagesAmul ReportUjwal JaiswalNo ratings yet

- Major Bank Performance IndicatorsDocument35 pagesMajor Bank Performance IndicatorsAshish MehraNo ratings yet

- WWW - Istructe.pdf FIP UKDocument4 pagesWWW - Istructe.pdf FIP UKBunkun15No ratings yet

- Chicago Electric Inverter Plasma Cutter - 35A Model 45949Document12 pagesChicago Electric Inverter Plasma Cutter - 35A Model 45949trollforgeNo ratings yet

- Health Education and Health PromotionDocument4 pagesHealth Education and Health PromotionRamela Mae SalvatierraNo ratings yet

- BoQ East Park Apartment Buaran For ContractorDocument36 pagesBoQ East Park Apartment Buaran For ContractorDhiangga JauharyNo ratings yet

- The Botanical AtlasDocument74 pagesThe Botanical Atlasjamey_mork1100% (3)

- Emergency Room Delivery RecordDocument7 pagesEmergency Room Delivery RecordMariel VillamorNo ratings yet

- Conceptual FrameworkDocument24 pagesConceptual Frameworkmarons inigoNo ratings yet

- The Changing Face of War - Into The Fourth GenerationDocument5 pagesThe Changing Face of War - Into The Fourth GenerationLuis Enrique Toledo MuñozNo ratings yet

- Bandung Colonial City Revisited Diversity in Housing NeighborhoodDocument6 pagesBandung Colonial City Revisited Diversity in Housing NeighborhoodJimmy IllustratorNo ratings yet

- Development of Rsto-01 For Designing The Asphalt Pavements in Usa and Compare With Aashto 1993Document14 pagesDevelopment of Rsto-01 For Designing The Asphalt Pavements in Usa and Compare With Aashto 1993pghasaeiNo ratings yet

- Scharlau Chemie: Material Safety Data Sheet - MsdsDocument4 pagesScharlau Chemie: Material Safety Data Sheet - MsdsTapioriusNo ratings yet

- WassiDocument12 pagesWassiwaseem0808No ratings yet

- Honors Biology Unit 2 - Energy Study GuideDocument2 pagesHonors Biology Unit 2 - Energy Study GuideMark RandolphNo ratings yet

- The Product Development and Commercialization ProcDocument2 pagesThe Product Development and Commercialization ProcAlexandra LicaNo ratings yet

- B. Ing Kls 6Document5 pagesB. Ing Kls 6siskaNo ratings yet

- Philips DVD Player SpecificationsDocument2 pagesPhilips DVD Player Specificationsbhau_20No ratings yet