Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Video: A Fairy Godmother in Adult Education?

Uploaded by

Grant Barclay0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

45 views4 pagesThis paper explores a use of video not as a presentation tool but one which encourages participation within a community of discourse. It highlights benefits and potentially problematic features and asks to what extent the use of video in this form is an appropriate fit for pedagogical purposes in a local church setting.

Original Title

Video: a fairy godmother in adult education?

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThis paper explores a use of video not as a presentation tool but one which encourages participation within a community of discourse. It highlights benefits and potentially problematic features and asks to what extent the use of video in this form is an appropriate fit for pedagogical purposes in a local church setting.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

45 views4 pagesVideo: A Fairy Godmother in Adult Education?

Uploaded by

Grant BarclayThis paper explores a use of video not as a presentation tool but one which encourages participation within a community of discourse. It highlights benefits and potentially problematic features and asks to what extent the use of video in this form is an appropriate fit for pedagogical purposes in a local church setting.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 4

Video: a fairy godmother in adult education?

‘[T]he term 'video' cannot possibly condense the narrative,

Grant Barclay, www.grant-barclay.co.uk documentary and descriptive range of moving images and sound. Video

Abstract is specifically produced to support education but it is produced for

many other reasons as well and we have only just begun to explore the

Video may support participation in a discourse community not only as a presentation tool or a educational possibilities of the medium.’ (Shephard, 2003, p.296)

means to disseminate final products for review or assessment, but as a facilitating technology, an

'early step' towards other engagement. This paper reports a simple use of video to capture early Video is already widely used as a means of expressing and communicating

contributions to a subject which is described in a text by a number of members of a faith considered views on a subject formed after considerable reflection, one example

community. Conversations responding to self-selected open questions were video recorded and

collected clips distributed as a resource to help prepare for group discussion. A range of potentially

being the recording of lectures:

useful and problematic features of using video to support participation was found, suggesting that ‘As a result, the production of video lectures is becoming more and

video may play a range of roles toward increasing participation among learners by developing more important, as video is one of the most powerful media to

identities of participation, offering rehearsal opportunities, supporting peripheral participation, and

offering vicarious learning opportunities of observing talk within a subject domain in a familiar

present information and students find video materials very compelling.’

manner. (Furini, 2009, p.77, emphasis added)

Another example is where learners present their views which include video format,

Introduction perhaps in producing reports for assessment (Farren, 2008, p.61). These are

examples of video used as a presentation or transmission tool, though video is not

Elements of the ‘Cinderella’ story (also known as Cendrillon, Aschenputtel or limited to these. Considered presentations may be distinguished from informal,

Cenicienta) may be seen as metaphors for uses of video to support learning. ephemeral conversations captured on video, for example through video-

Attending the ball, in the tale, results from much preparation and is a location for conferencing facilitiesor consumer web-based applications:

demonstrating certain skills. Video is a means of transmitting the end result of much

preparation both by academic staff producing bespoke video material and students ‘The rapid expansion of public video sites such as YouTube

producing final reports for assessment. (www.youtube.com) or MetaCafe (www.metacafe.com) have lead to a

renaissance of homeproduced video as a popular creative medium for

Cinderella’s household role fulfilling necessary domestic chores in the story is entertainment and even education.’

essential though perhaps little noticed. Video-recording lectures to permit access by (Bijnens, Vanbuel, Verstegen & Young, 2006, p.6)

students at convenient times or places may similarly fulfil a helpful service, whose

production may be un-noticed through familiarity. A greater range of possible educational uses for video are becoming apparent.

Watching video of whatever type may be considered more passive than conversing

The principal metaphor considered in this paper is the process initiated by fairy with someone physically present, most obviously because there is no possibility of

godmother by which Cinderella can attend the ball. Participation is the focus, for direct interchange. How, then, may video encourage participation?

Cinderella’s lack of necessary resources preludes this until the fairy godmother makes

it possible for her to take part. What role may video play in supporting participating

in learning activities with others, particularly ones in which they might otherwise be Video to encourage participation

hesitant to become involved? Video may be used not merely as a presentation tool but as a communication

An additional issue is that Cinderella’s participation was still limited and ended at resource by learners who, in considering a subject or issue, share early thoughts

midnight, albeit with one fragile artefact remaining, a glass slipper fitting only rather than final views in a video-recorded conversation which is made available to

Cinderella’s foot. Is video a similarly fragile resource with limited use, or does it have other learners. This conversation may be supported by providing initial information

a wider fit? The issues of participation and fit are explored in this paper after the and views in a printed text together with video clips of other learners’ early

diverse nature of video is described. thoughts. How would text and clips like this influence forming and articulating one’s

early view and support reflection on the subject?

The diversity of video Vicarious learning theory (Mayes, Dineen, McKendree & Lee, 2002) argues that

watching others attempting to learn, or overhearing learners’ dialogue through

Video is a diverse medium within and beyond educational purposes: which concepts are articulated and shared, may support observers’ learning.

Observational spiritual learning suggests that individuals develop perspectives on faith

by looking to others’ examples (Oman and Thoresen, 2003a, 2003b). Bandura (2003,

p.171) supports the contention that spiritual modelling is influential in faith

development.

Communities of practice understands learning as:

‘...chang[ing] who we are by changing our ability to participate, to

belong, to negotiate meaning. And this ability is configured socially with

respect to practices, communities, and economies of meaning where it

shapes our identities.’ (Wenger, 1998, p.226)

Learning may be understood to change learners both cognitively in terms of

reflections on a subject and socially in relation to others. Subject knowledge and

skills, both necessary for participation may be developed along with increasing

understanding of the practices in which one engages in participating, together with

awareness of one’s developing ability and right to engage in community activities. This

view suggests experience and participation are components of learning, not

independent but interacting upon each other.

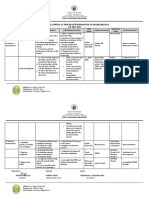

Figure 1 Production process for resource

The investigation

Fifteen church-goers volunteered to consider an issue and were supplied with a

previously published text and fifteen open questions designed to support them

describing their views about the text and issues it raised, as well as video-clips of

other people offering their views. A church congregation is a setting in which

participants expect to learn (Barclay, 2006) and in which a range of media is currently

used including books, audio CDs, websites, magazines and lecture-type presentations.

Christian faith encourages individual theological reflection (Astley, 2002a) and the

sharing of views (Astley, 2002b), though the personal nature of the subject may

inhibit such discussion in a Scottish Presbyterian culture. Reflection on the text and

wider issue was encouraged as participants responded to one or more of the open

questions in a video-recorded conversation with the researcher. Edited video-clip

contributions produced with Pinnacle Studio (Avid Technology, 2004) were

incorporated into the resources available to subsequent contributors in a process

indicated in Figure 1.

Discourse was encouraged in a later face-to-face group discussion, for which a

resource containing the text and all video-clips was distributed in advance. Informants

later described in research conversations and a short written questionnaire how the

the resources and their contributions influenced their later participation in a

discussion group. Phenomenographic analysis of transcripts permitted a range of

experiences of interactions among the four elements of reading the text, articulating a

view, watching video-clips and discussing in a group to be classified. All written

responses from questionnaires are shown in Figure 2 and were obtained after Figure 2 Relations among elements in resource

informants had reflected on their experiences in research conversations. They are producer, video was found to be useful to support articulation and listening leading

presented as a summary of experiencing the four activities mentioned above. to cognitive, social and affective benefits. Initially considered a learning resource,

Reading the text was reported as helpful in providing something to base one’s video became an integral part of the instructional design. However, watching video

thought on as well as providing the author’s perspective and providing information. was initially experienced as a peripheral activity, compared with the community’s

The presence of a text meant the issue had to be addressed which some found core activity of discussing in group discussion. The facility to observe before

challenging. One informant felt the text, extending in this case to 1,200 words, was contributing and then contribute through a conversation among two (in the video-

too long to concentrate on. recorded conversation) prior to speaking in a larger, ‘live’ group, may be seen as a

form of peripheral participation focusing on greater participation (Lave & Wenger,

Watching video-clips of others was reported as helpful because of the new 1991, p.29).

perspectives which were made available, broadening possible ways of considering the

subject and challenging existing views: others’ varied views supported individual Cognitive reflection, that is working at greater thoughtfulness (Dewey, 1913, p.58),

cognitive reflection. Watching peers’ articulations was intriguing, demonstrated that a was encouraged through a demand for some articulation in the video-recorded

potentially daunting activity was achievable and illustrated the ‘ordinariness’ of conversation, removing the possibility of never articulating one’s views. It also meant

contributions, encouraging articulation of views perceived too mundane to be that prior to the discussion all participants had rehearsed articulating their views

valuable: whilst aware that these were amenable to alteration and development. This

articulation was not merely an unrealistic rehearsal but was necessary to produce a

The ability to stop or view videos again gave space to consider the subject, a feature video-clip to help others consider the subject. This requirement to speak about

it shared with the text which could be re-read. However, seeing familiar faces on- aspects of the text meant it had to be read and considered, described by one

screen supported a sense of presence (Knudsen, 2004, p.6) or companionship informant as a useful ‘gentle push’. Having been thus pushed, confidence to

reported as cognitively supportive, something not provided by the text. The sole contribute in the face to face group appeared to be encouraged.

criticism of video was that watching oneself was initially unusual and unpleasant.

Anxiety associated with anticipating the conversation task was lessened through the

Articulating a view in video-recorded conversation was reported as helpful in possibility of editing the video, rendering poorer articulations invisible to others.

encouraging contributors to realise they had a valid contribution to make and helping Additionally, the initial articulation was in a small one-to-one conversation and not a

form that contribution which needed to be understood by contributors before its performance to a group. Encouragement was further provided by watching peers’

articulation. Most church-goers’ discussions are in discourse and using video similar activity in video-clips. Zozzou, Van Mele, Vodouhe and Wanvoeke (2009)

permitted these to be captured in a familiar medium. Seeking written answers would found that training videos in which fellow women rice farmers demonstrated

have been a more unusual request. Although appearing in a video-clip appeared preparation techniques resulted in greater uptake of the technique than training

daunting, some described the experience as helpful, even easier than in a group workshops, suggesting that observing peers’ activities may encourage participation.

setting, and that having one’s views listened to was positive. The sole negative

comment related to perceptions about appearance on video. Using video encouraged social learning including an identity of participation among

contributors. This supported some to perceive their right to belong to this

Participating in a discussion encouraged confidence to view oneself as an active community, or that that they had valuable contributions, or that offering them was a

member of the community as well as supporting reflection on the issue through contribution supporting others to reflect on the issue.

hearing other people’s views. One noted benefit of the discussion was being able to

develop early contributions in video-clips. Social aspects of group discussions were An appropriate fit?

also valued and the sole negative comment was of perceiving being judged for

contributions made. The text and video clips were produced using Pageplus (Serif, 2004) in a multimedia

resource as a PDF file with hyperlinks to video files all of which were stored and

Discussion distributed on CD-ROM. Nevertheless a number of enthusiastic participants had no

access to computers nor necessary computer skills. This necessitated producing the

Lane (2007) notes that video frequently involves passive watching, an educational material in a second form, namely printed sheets and a DVD-disc playable on a

limitation. This investigation made use of video both to encourage articulations of domestic DVD player. This proved adequate to enable participation by those

early thoughts and to capture these for the benefit of the group. Achieved using without computer facilities.

modest available technology though requiring considerable time input by the resource

No investigation was conducted to determine whether other possible contributors References

were discouraged by the thought of appearing in video, an initially daunting prospect Astley, J. (2002a). Ordinary Theology. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing.

nonetheless reported as useful once completed. No comparison was made between

contributing initially on video or in a small group, though there were indications that Astley, J. (2002b). In Defence of Ordinary Theology. British Journal of Theological

the small-scale conversation, the ability to repeat the contribution on video and the Education 13(1) pp.21-35.

open questions provided helpful initial support to articulate views which could then Avid Technology. (2004). Pinnacle Studio (Version 9.4). [Computer program].

be developed in a ‘live’ small group setting. Available at : http://www.pinnaclesys.com (Accessed: 14 May 2009).

Using a text with open questions appeared to provide a ‘shoehorn’ to ease people Bijnens, M., Vanbuel, M., Verstegen, S. and Young, C. (2006). Handbook on Digital

into into the task of articulating views in a video-recorded conversation. It also Video and Audio in Education. Glasgow Caledonian University: The VideoAktiv

provided common information about the issue, presented an argument and offered Project. Available at: url http://www.atit.be/dwnld/VideoAktiv_Handbook_fin.pdf

ideas from which one could differ in a format which was accessible and familiar (Accessed: 13 August 2008).

though which some nevertheless found demanding. Dewey, J. (1913). Interest and effort in education. Bath:Cedric Chivers Ltd.

Farren, M. (2008). Co-creating an educational space. Educational Journal of Living

Conclusions Theories 1(1) pp. 50-68.

Educational video may be considered a ‘polished product presenting final views’ Furini, M. (2009). Secure, Portable and Customizable Video Lectures for E-Learning

though in fact video enables a range of uses. Whilst used widely by those who are on the Move. Informatica 33 pp.77-84

expert in a subject or have come to some knowledgeable position to present

information, there is potential for it to be used productively earlier in the learning Knudsen, C.J.S. (2004). Presence Production. Unpublished PhD Thesis. Stockholm:

process as investigated here. Royal Institute of Technology.

Informal ephemeral video now more widely used captures a different mode of Lane, J. (2007). Digitising our Learning: An innovative trial of a new teaching

articulation than written material, more commensurate with actual practice in this technology. Journal of the Australian Council for Computers in Education 22(1)

setting. It permits otherwise fleeting comments to be captured, stored and viewed pp.34-37.

more widely and was found to encourage greater participation both because it Lave, J. and Wenger, E. (1991). Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation.

revealed others’ contributions as proximate achievable models and because the Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

variety of views presented stimulated individual reflection. Mayes, T., Dineen, F., McKendree, J. and Lee, J. (2002). Learning from Watching

Finally video-clips were persistent and available on demand, simultaneously similar to Others Learn In Steeples, C. and Jones, C. (Eds) Networked Learning: Perspectives

and different from Cinderella’s slipper. Informal video capturing early thoughts may and Issues. London:Springer-Verlag. pp. 213-227.

be one tool to encourage broader participation, though resource implications for its Mayes, J.T., and Crossan, B. (2007). Learning Relationships in Community-Based

use, similar to those faced by the prince’s in the tale, need to be considered carefully. Further Education. Pedagogy, Culture & Society 15(3) pp.291-301.

Nevertheless the widespread adoption of informal video and its ever-broadening

acceptance offers some potential for its fairy-godmother like role, for a number of Serif (Europe) Ltd. (2004). PagePlus (Version 10) [Computer program]. Available at

reasons outlined here, in supporting participation in communal reflection on issues url: http://www.serif.com (Accessed 14 May 2009).

and hence providing opportunities for learning. Shephard, K. (2003). Questioning, promoting and evaluating the use of streaming

video to support student learning. British Journal of Educational Technology 34(3)

Note pp.295-308.

This paper was first presented at DIVERSE 2009 Conference, Aberystwyth University, Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of Practice: learning meaning and identity.

UK. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Contact Zozzou, E., Van Mele, P., Vodouhe, S.D. and Wanvoeke, J. (2009). The power of

Grant Barclay, St Kentigern’s Parish Church, Kilmarnock, UK. video to trigger innovation: rice processing in central Benin. International Journal of

Website: www.grant-barclay.co.uk. Email: grant.barclay@tiscali.co.uk Agricultural Sustainability 7 pp.119-129.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- dp2 Unit Planner - Civil RightsDocument5 pagesdp2 Unit Planner - Civil Rightsapi-252539857No ratings yet

- Theme Lesson PlanDocument3 pagesTheme Lesson PlanTricia Tricia67% (3)

- 2019 Pennington Primary - Partnership Program Eot 3-FinalDocument3 pages2019 Pennington Primary - Partnership Program Eot 3-Finalapi-424238197No ratings yet

- Web 2Document2 pagesWeb 2api-653337422No ratings yet

- GRammar - Lesson Plan PDFDocument1 pageGRammar - Lesson Plan PDFolivethiagoNo ratings yet

- Cornel de Villiers: Career ObjectivesDocument3 pagesCornel de Villiers: Career Objectivesanon-577995100% (2)

- CHAPTER 3 Learning Outcomes and CMOsDocument4 pagesCHAPTER 3 Learning Outcomes and CMOsLJ PaguiganNo ratings yet

- Activity Guide and Evaluation Rubric - Post-Task - Final Exam - Writing and SpeakingDocument8 pagesActivity Guide and Evaluation Rubric - Post-Task - Final Exam - Writing and SpeakingMaBel Alvarez MNo ratings yet

- Simulation-Test-3 MTORC BLEP Reviewer 2020Document29 pagesSimulation-Test-3 MTORC BLEP Reviewer 2020Stan Erj40% (5)

- Syllabus Pagsasaling WikaDocument6 pagesSyllabus Pagsasaling WikaMarvin Ordines100% (4)

- SDFFDDocument53 pagesSDFFDWarren Drig NovioNo ratings yet

- Self Leadership The Definitive Guide To Personal Excellence 1st Edition Neck Test BankDocument11 pagesSelf Leadership The Definitive Guide To Personal Excellence 1st Edition Neck Test Bankanwalteru32x100% (25)

- WHLP - Week 4 - Food (Fish) ProcessingDocument1 pageWHLP - Week 4 - Food (Fish) ProcessingRosalyn CanilangNo ratings yet

- (Lecture Notes in Computer Science 10949) Simon K.S. Cheung, Lam-For Kwok, Kenichi Kubota, Lap-Kei Lee, Jumpei Tokito - Blended Learning. Enhancing Learning Success-Springer International Publishing (Document444 pages(Lecture Notes in Computer Science 10949) Simon K.S. Cheung, Lam-For Kwok, Kenichi Kubota, Lap-Kei Lee, Jumpei Tokito - Blended Learning. Enhancing Learning Success-Springer International Publishing (d-icha100% (1)

- Curriculum Map in Technology and Livelihood Education Grade 8Document3 pagesCurriculum Map in Technology and Livelihood Education Grade 8aejae avilaNo ratings yet

- FS 6 Episode 1 NewDocument11 pagesFS 6 Episode 1 NewJohn Rose EmilananNo ratings yet

- READING REPORT in - THCORE1 - Philippine Culture & Tourism GeographyDocument3 pagesREADING REPORT in - THCORE1 - Philippine Culture & Tourism GeographyArcielyn ConcepcionNo ratings yet

- TRF Ans 2fDocument13 pagesTRF Ans 2fKiffa AngobNo ratings yet

- INDIVIDUAL ACTION PLAN - SY2022 2023 NoelDocument2 pagesINDIVIDUAL ACTION PLAN - SY2022 2023 NoelNgirp Alliv Trebor100% (1)

- Reading Assignment#1Document22 pagesReading Assignment#1mirzaazzaleaNo ratings yet

- Allama Iqbal Open University, Islamabad: (Early Childhood Education and Elementary Teacher Education Department)Document2 pagesAllama Iqbal Open University, Islamabad: (Early Childhood Education and Elementary Teacher Education Department)Bilal SattiNo ratings yet

- Bridgend Christian School 2007 EstynDocument44 pagesBridgend Christian School 2007 EstynBCSchoolNo ratings yet

- PhilosophyDocument3 pagesPhilosophyapi-487676510No ratings yet

- The Impact of Flood To The Academic Performance and Time Management of Selected Students of San Pedro National High SchoolDocument18 pagesThe Impact of Flood To The Academic Performance and Time Management of Selected Students of San Pedro National High SchoolMerlyn EspinoNo ratings yet

- Formative and Summative Assessment Formative AssessmentDocument11 pagesFormative and Summative Assessment Formative AssessmentClemente AbinesNo ratings yet

- Pedagogy McqsDocument44 pagesPedagogy McqsDahoodAhmedNo ratings yet

- Accomplishment ReportDocument4 pagesAccomplishment ReportacenasapriljeanNo ratings yet

- Stages of Language Acquisition in The Natural Approach PDFDocument6 pagesStages of Language Acquisition in The Natural Approach PDFNovita SariNo ratings yet

- DLL in Organization and ManagementDocument4 pagesDLL in Organization and ManagementMarivic PuddunanNo ratings yet

- Rpms Template 101Document17 pagesRpms Template 101donna kristine DelgadoNo ratings yet