Professional Documents

Culture Documents

MYTH IN ACTION Greek Heritage in Polish Theatre (Kantor, Grotowski, Staniewski)

Uploaded by

Mirek Kocur0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

104 views7 pagesPolish culture is based on a peculiar paradox, as there has been no elaborate system of myths. Ancient Greek myths lent us strength to survive and gave meaning to our struggles. The Return of Odysseus was staged at the main Krakow railway station, crowded with Nazi soldiers and p olice.

Original Description:

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

TXT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentPolish culture is based on a peculiar paradox, as there has been no elaborate system of myths. Ancient Greek myths lent us strength to survive and gave meaning to our struggles. The Return of Odysseus was staged at the main Krakow railway station, crowded with Nazi soldiers and p olice.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as TXT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

104 views7 pagesMYTH IN ACTION Greek Heritage in Polish Theatre (Kantor, Grotowski, Staniewski)

Uploaded by

Mirek KocurPolish culture is based on a peculiar paradox, as there has been no elaborate system of myths. Ancient Greek myths lent us strength to survive and gave meaning to our struggles. The Return of Odysseus was staged at the main Krakow railway station, crowded with Nazi soldiers and p olice.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as TXT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 7

MYTH IN ACTION

[lecture delivered on the Conference Ancient Myths in the Contemporary Theatre i

n Olympia, Greece, August 1st, 2002]

Greek Heritage in the Polish Theatre

Polish culture is based on a peculiar paradox. Our tradition and historical cons

ciousness are rich in rituals and martyrs, yet they function in a mythological v

acuum, as there has been no elaborate system of myths to help us understand thes

e ceremonies and sacrifices. Since we have traditionally claimed the Mediterrane

an civilisation as the source of our own culture, for many centuries we have als

o been relying on ancient Greek myths, albeit in the form passed on to us by the

Romans. There was a time when many educated Poles were bilingual, and their Lat

in was better than Polish. Throughout our history, as we were losing our indepen

dence, ancient Greek myths, told again and again, lent us strength to survive an

d gave a meaning to our struggles. They ultimately became an integral part of ou

r identity. In order to show how an ancient myth can be used as a device in cons

tructing modern identity, I will look at the work of three Polish theatre artist

s.

Odysseus in the Theatre of Death

In 1944, in the town of Kraków, then occupied by the German military forces, Tadeu

sz Kantor (1915-1990), a Polish painter and visionary theatre director, was plan

ning to stage at the main Kraków Railway Station, crowded with Nazi soldiers and p

olice, The Return of Odysseus - a drama by another Polish visionary Stanisław Wysp

iański (1869-1907). At that time the Nazis were in full retreat and Kantor envisag

ed Odysseus as a German Soldier coming home by train after the German surrender

at Stalingrad (02.02.1943). A war criminal and a traitor, Odysseus was also comi

ng from the world of ancient fiction to the real world. At the dirty and ugly st

ation nobody would notice him, nobody would care who he is and what he did. Ther

e was no Ithaca anymore. The station was an embodiment of a reality of a lower o

rder.

Of course, this idea has never materialised. Kantor had to stage his play in a p

rivate apartment. But still people who let him do it were risking their lives, a

s was the artist himself. There was a Nazi police station on the other side of t

he street and at any moment the Germans could break in. Moreover, the performanc

e itself referred to the war events directly. When Odysseus directed his bow tow

ards the suitors, the audience could hear the rattle of a machinegun coming from

the real loudspeaker stolen from the street. On the entrance doors to the room

where the performance took place Kantor wrote: "You never enter theatre with imp

unity".

There was not a set design or props; the performance was staged in a room destro

yed by the war. The spectators were not separated from the artists. There was no

isolated space for illusion. Everything had to be real. But the reality of wart

ime was the reality of the lowest order. The objects used in the performance wer

e the "poor objects" found on the street. "This everyday REALNESS - explained Ka

ntor, who was the best commentator of his own works - which was firmly rooted in

both place and time, immediately permitted the audience to perceive this myster

ious current flowing from the depth of time when the soldier, whose presence cou

ld not have been questioned, called himself by the name of the man who had died

centuries ago". Only the huge canon was artificial: made of wood, it placed the

war in the realm of fiction. Or more accurately: in the realm of death.

Odysseus, an Unknown Soldier in a dirty old mantel and a Wehrmacht helm, was ret

urning from the realm of Death. Kantor discovered art as a vehicle to cross the

gap between the other world and the real world, between death and life, between

fiction and reality. The Return of Odysseus was the first manifestation of his T

heatre of Death. The returning Odysseus became the prototype for all latter char

acters in Kantor's theatre.

But Kantor was an eternal pilgrim himself, he internalized the great Homeric myt

h by repeating the journey of Odysseus with his art and with his life. In 1955 h

e founded Cricot 2 Theatre, named after the theatre of painters, which existed i

n Kraków in the years 1933-1939. The French-sounding term "cricot" was an anagram

from Polish "to cyrk", "this is a circus". Kantor's theatre never had any legal

status or any building for staging performances. It was a genuine travelling tro

upe. The world of performance was Kantor's real home and his journey was a spiri

tual one, towards self-discovery.

In 1975 Kantor staged his greatest performance, The Dead Class (Umarła Klasa). A f

ew years earlier, during holidays on the Polish coast, he came upon a small vill

age school and when he looked inside the empty classroom through the dirty windo

w he discovered "the reality of memory". In The Dead Class Kantor brought thirte

en old people back from their death to the school. In the class they met thirtee

n manikins (or better: puppets) of children who resembled them when they were yo

ung. They had to sit few lessons before they could return to the realm of Death

again. The performance had a structure of a spiritualistic séance. The actors were

haunted by their characters; they were the living people inhabited by the dead

ones. There was no room for psychological acting, or more accurately: there was

no acting at all. Kantor required his actors not to embody a character but to pr

ecisely accomplish a real task, as for example "packing of the pack". For Kantor

, actors were crooks who unsuccessfully tried to cheat the audience. He himself,

always present on the stage, directed the whole ceremony like a conductor or a

priest rather than a director. All these ghosts were projections of his Memory.

During the show, it was the Memory that had to be real, not the actors.

In his next performance, Wielopole, Wielopole (1980), Kantor put on the stage hi

s own dead family. He mentally returned home to the village where he was born in

1915. The performance took place in the family room, which did not resemble any

space at Kantor's home in a Polish-Jewish village Wielopole, but was the Room o

f Memory, an autonomous space created by the simultaneous universes of a physica

l world overlapping the world of memory. Wielopole, Wielopole was created not in

Poland but in Florence, Italy. Florence, once an intellectual and artistic cent

re of Italy, had become his second hometown. Both cities, Florence and Kraków, wer

e depositories of glorious traditions. Wielopole, Wielopole was Kantor's first s

cript which did not include any quotations from the existing dramas.

His next show, Let the Artists Die (1985) continued Kantor's road towards self-d

iscovery. The structure of the revue, as he called it, was based on his own life

, from his birth till his death. It was a bitter testimony to his failure to bec

ome his real self. Kantor exposed life as a process of continuous dying. Continu

al transformations made forging an identity impossible. The revue was created in

Nuremberg, a hometown of another ill-fated artist, a great Renaissance sculptor

Weit Stoss (1447-1533), who was one of the main characters in Let the Artists D

ie. Kantor was similarly damned in his hometown Kraków where he usually was given

bad reviews and had no place to work. Weit Stoss, accused of not paying his debt

s, had both his cheeks pierced by the Nuremberg magistrates. As a motto to his p

erformance Kantor chose: "Artists are victims of a society".

The last performance Kantor managed to produce for his Cricot 2 Theatre had a ve

ry meaningful title: I Shall Never Return (1988). For this show he created his o

wn manikin. He came to the end of his road. Now he himself was haunted by the gh

osts from his previous performances. The show began with his own voice coming fr

om the loudspeaker: "An artist has to be at the bottom"... He himself was sittin

g at the table on the stage watching the procession of his own creations. In the

middle of the performance his other Self came on the stage, the manikin of a yo

ung Kantor, dressed as a groom. He was accompanied by an empty coffin, his bride

. At the end of the show the real Kantor was approached by the characters from T

he Return of Odysseus. The suitors brought him a coffin. And then Kantor read fr

om the old script of the original production: "In my fatherland I have found a h

ell". He died two years later, while working on his next performance, Today Is M

y Birthday. He spent his last days completely alone in Kraków. After working durin

g the day on the new performance, he came home and wrote in his diary: "What emp

tiness surrounds me", "Nobody comes. I think, they are afraid", "I have so much

to do".

Kantor's travelling theatre was the twentieth century version of an old Greek my

th. Like Odysseus he went into the realm of Death and then returned to discover

himself in his own art. With his death his theatre inevitably ceased to exist. B

ut the Theatre of Death was also a testimony to the 20th century notorious for t

otalitarian regimes and genocide. Kantor discovered the enduring power of the re

ality of the lowest order. Like a totalitarian dictator he reduced his actors in

to Bio-objects. In exposing their humiliation, he revealed the greatness of huma

n beings. The act of a genius transformed the Bio-object into the masterpiece. L

ike Homer in his epics, Kantor recounted brutal and heroic events and proved tha

t art will triumph over war and politics. While revealing his own Myth he has gi

ven shape to our own Memory.

Prometheus in the Poor Theatre

Kraków is the Polish necropolis, where our greatest kings and poets had been burie

d. Founded in the eight century AD, it was the capital city of Poland from 1305

to 1595, and today it is still an important cultural centre. The Wawel, the cast

le where the Polish kings resided, has the same significance for the Poles as th

e Athenian Acropolis for the Europeans. Here, in the years 1903-1904 Stanisław Wys

piański wrote Acropolis, his most important and difficult to interpret drama. The

narrative is simple. On the night of the Resurrection, before Easter Sunday, fig

ures descend from Wawel tapestries to recreate the great myths from ancient Gree

ce and the Bible: the Trojan War, Paris and Helen, Jacob's wrestling with the An

gel, Jacob and Esau.

At the time when Wyspiański was composing his play, Cracow was both: the Polish Ac

ropolis, a monument to our heroic past and a cradle and a grave of the national

identity, and a huge ruin. Like the Athenian Acropolis the Wawel castle was wrec

ked by foreign invaders. This meant that the play's title Acropolis had a ring o

f ambiguity about it.

In 1962, in a small town of Opole, 170 km from Kraków and 80 km from a former conc

entration camp in Auschwitz, a twenty-nine-year-old director Jerzy Grotowski mad

e a decision to stage Acropolis in his Laboratory Theatre. Grotowski and his lit

erary adviser Ludwik Flaszen (born in 1934) could not ignore the fact that they

read the play in the aftermath of the Holocaust. Their collaborator was Józef Szaj

na (born in 1922), a well-known painter and a survivor of the Auschwitz camp. He

decisively inspired the shocking and petrifying vision of the Acropolis as the

crematory of civilisations. The burial ground of tradition was confronted with t

he reality of extermination camps. The motto to the production was taken from th

e poem of Tadeusz Borowski (1922-1951), who also had been a prisoner in Auschwit

z:

Its just scrap iron that will be left after us

And a hollow, derisive laughter of future generations (trans. B. Taborski).

Grotowski's Acropolis became thus a poetic vision of an extermination camp. The

drama was acted among the spectators who were placed on different levels all ove

r the acting space. But there was no direct contact between the actors and the a

udience. They inhabited two separate and opposite worlds: the spectators belonge

d to the realm of Life, the characters of the play to the realm of Death. Flasze

n explained: "The physical closeness on this occasion is congenial to that stran

geness: the audience, though facing the actors, are not seen by them. The dead a

ppear in the dreams of the living odd and incomprehensible. The fact that they a

ct in different places of the room - individually, and sometimes simultaneously

- is intended to create the suggestion of spatial vagueness and obtrusive ubiqui

ty".

In the middle of the acting space stood a huge chest, with iron junk heaped on t

op of it: rusted stove pipes of various lengths and widths, a wheelbarrow, a bat

htub, hammers and nails. As the action progressed, the actors-prisoners were con

structing out of those objects an absurd civilisation, a civilisation of a gas c

hamber, symbolised by the stove pipes which surrounded the whole room as the act

ors hung them by strings or nailed them to the floor. Their costumes were just p

ieces of sack cloth with holes in them, put over their naked bodies; on their fe

et they had heavy wooden clogs which made an unbearable noise, on their heads th

ey had dark, non-descript berets. The actors performed the absurdly aimless work

of convicts, prescribed by prison camp regulations. Thus, in Acropolis, ancient

and biblical myths were performed by the prisoners of a concentration camp. Wys

piański's drama ends with the Resurrection and the apotheosis of Christ; this perf

ormance ended with a procession of prisoners who triumphantly carried a headless

mannequin whom they took for the Saviour and disappeared one after another into

a crematorium oven. Instead of an identification Grotowski proposed a confronta

tion with a myth.

There was no individual hero. Actors were prisoners and they were made into iden

tical beings, bereft of any distinguishing marks of sex, age, or social class. S

ix actors presented an ideal ancient chorus. Their masks were created solely by

the facial muscles, frozen in a bizarre grimace. Acropolis was a decisive step t

owards a poor theatre. Flaszen explained: "The production was constructed on the

principle of strict self-sufficiency. The main commandment is: do not introduce

in the course of action anything which is not there from the outset. There are

people and a certain number of objects gathered in the room. And that material m

ust suffice to construct all circumstances and situations of the performance; th

e vision and the sound, the time and space. The poor theatre: to extract, using

the smallest number of permanent objects - by magic transformations of objects i

nto objects, by multi-functional acting - the maximum of effects. To create whol

e World, making use of whatever is within reach of the hand".

After the collective confrontation with a myth in Acropolis, the natural consequ

ence was to take one step further and make actors confront a myth individually o

n the most intimate level. Grotowski explained: "I demand from the actor a deed,

in which is contained his relation to the world. In a single reaction the actor

ought to open, as it were, successive layers of his personality, from the biolo

gical-instinctive, through thought and consciousness, up to the peak which is di

fficult to define, but in which everything unites in one; there is in it the act

of totally revealing oneself, sacrifice, sincerity, which translates all the co

nventional barriers and which contains, both at once, eros and caritas, I call i

t the total act. This act should function as a self-revelation. This act can be

accomplished only on the basis of one's own life - it is an act which strips one

bare, deprives, reveals, discovers. The actor ought not to act, but penetrate t

he areas of his own experience with his body and voice. At the moment the actor

achieves this act, he becomes a phenomenon hinc et nunc; he does not tell a stor

y, or create an illusion - he is there in the present. If the actor is able to a

ccomplish an act of this kind, and moreover in confrontation with a myth which r

etains its validity for us - the reaction which he evokes in us contains a pecul

iar unity of what is individual and what is collective".

In the total act the actor was to present here and now not only himself but also

the myth. A classic example of the total act was the role of Ryszard Cieślak (193

7-1990) in The Constant Prince (1965), based on Calderon's drama in the free tra

nslation of a great Polish Romantic poet, Juliusz Słowacki (1809-1849). Grotowski

transferred the action from a historical to a universal level. Cieślak had to face

the myth of Christ. On a personal level he verified the myth referring it to hi

s most intimate memories. Grotowski demanded that the actor remain independent a

nd pure to the point of ecstasy. Cieślak achieved this state by recalling his firs

t love encounter with a girl during the scenes of the prince's martyrdom. In the

performance his total act was contrasted with the behaviour of the King's court

, "the community of fanatical conformists". To enhance the tragedy of a human se

lf-sacrifice Grotowski radically separated the audience from the actors. The spe

ctators were placed behind a high fence; like a public in the Ancient Rome obser

ving bloody games they looked down on the actors. "In the middle of the room the

re was a dais which - according to the requirements of the action - could serve

as a prisoner's bed of misery, an executioner's platform, a table for surgical o

perations and a sacrificial altar". Theatre was transformed into a sanctuary, wh

ere an ancient myth was performed and actualised, and where an actor became a Ho

ly Actor.

The production of The Constant Prince and Cieślak's great creation marked the begi

nning of a long process of research and workshops to accomplish the total act no

t just by one actor but also by the entire company of the Laboratory Theatre. On

19 July 1968 a single open rehearsal took place in Wrocław, followed on 11 Februa

ry 1969 by the official premiere of Apocalypsis cum Figuris. The title alluded t

o the last work of Adrian Leverkühn, a hero of Doctor Faustus (1943-1947) by Thoma

s Mann (1875-1955), who "as a man of thirty five, under the influence of the fir

st wave of euphoric inspiration, composes his main work, or his first great work

, Apocalypsis cum Figuris, to fifteen woodcuts by Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528), or d

irectly based on the text of the Revelation, in an uncannily short time." In 196

8 Jerzy Grotowski was also thirty-five year old and Apocalypsis came to be consi

dered his most outstanding work, and the fullest work of his actors all of whom

achieved creations of exceptional intensity.

Grotowski stated: "In Apocalypsis we departed from literature. It was not a mont

age/compilation of texts. It was something we arrived at during rehearsals, trou

gh flashes of revelation, trough improvisations. We had material for twenty hour

s in the end. Out of that we had to construct something which would have its own

energy, like a stream. It was only then that we turned to the text, to speech.

From the various texts a language without an author was created, a language of t

he human kind. In what we are doing now there are no quotations. The word appear

s when it is indispensable for us". Apocalypsis was his last performance. In the

early seventies Grotowski proclaimed the end of the "Theatre of Productions" (1

957-1968). Now spectators were required to actively participate in workshops and

para-theatrical events, and in the works of the international Theatre of Source

s (1976-1982).

In 1982, following the imposition of the Martial law, Grotowski left Poland. Aft

er few years of lecturing at American universities, he started in 1985 in Italy

his Ritual Arts project. With a small group of young collaborators he founded th

e Workcenter of Jerzy Grotowski in Pontadera, Tuscany. Their work focused on anc

ient vibratory songs. These songs derived from ritual tradition were used as a d

evice for the inner transformation. To activate "inner action" in the performers

, Grotowski developed special performing structures, which were called simply Ac

tions. Although the main goal of Action was to transform the doers, Grotowski in

vited to Pontadera guests to witness the process. In 1998 he and his collaborato

rs visited Wrocław and presented Action to small chosen audience. We could witness

how ancient ritual songs revealed their great mythical power again. In these so

ngs ancient myths regained their universal dimension.

For Grotowski, myth was a vehicle for collective and personal transformation. Tr

ue to this idea, several times in his life he himself underwent a radical transf

ormation. He changed from a corpulent party member in dark glasses, through a sl

im hippie with long hair, into a white-bearded recluse. He constructed and recon

structed his own Self as an artist. His final creative achievement was to become

a myth himself.

Rural Dionysos

The third artist is Włodzimierz Staniewski (born in 1950), a founder and a leader

of the Centre for Theatre Practice in Gardzienice, a small village in south-east

ern Poland. In 1976, Staniewski, after parting his ways with Grotowski, moved to

the rural and backward areas in order to find a new environment, a new audience

and new resources for the theatre. This most Dionysian of Polish artists used t

he spirit of music as a creative force for his performances and for two original

theatrical practices - The Expeditions and The Gatherings. For Staniewski, like

for Grotowski, myths are still vibrating in "the Musicality of the Earth". But

their artistic roads were very different. Grotowski was more like a scientist wh

o put the actors in the laboratory in order to stimulate and study their transfo

rmations. Staniewski has left the theatre and took the actors on a journey to br

ing his art directly to the people, like ancient Thespis - if there is any truth

in Horace's words that Thespis took his plays about on wagons.

Initially the Expeditions were undertaken every month, mainly in the eastern reg

ions of Poland where many ethnic minorities including the Byelorussians, Gypsies

and Lemks still live. During such Expeditions Staniewski organised the Gatherin

gs. In the evening the actors performed a play for the villagers and later in th

e night the villagers were asked to sing their local traditional songs. The Gath

erings provided the material for Gardzienice?s early performances: Sorcery (1981

) and The Life of Archpriest Avvakum (1983). Sorcery was based on the Part Two o

f the drama Forefathers Eve (1821) by a Polish great Romantic poet Adam Mickiewi

cz (1798-1855). Using folk rituals and the structure of a Greek tragedy Mickiewi

cz sought to create a Slavic national myth, which in his opinion the Poles did n

ot possess. Staniewski did not propose any new interpretation, but repeated Mick

iewicz's creative procedure, fusing the elements of a high and low culture. Sorc

ery arose from the fragments of the drama and from the songs and gestures of vil

lage people. Russian and Byelorussian songs and Hasidic Jews whirling dance serv

ed to recall the original context of an ancient Slavic ceremony resembling the a

ncient Anthesteria, a festival of Dionysos which was associated with the new win

e and a commemoration of the dead.

The source and inspiration for The Life of Archpriest Avvakum was The Life writt

en by 17th century Russian Orthodox fanatic Avvakum Pietrovich (1620-1682), burn

t at the stake. Staniewski's actors lent life and energy to the hieratical figur

es "frozen" in the old Russian Holy Icons. It was of a huge significance that th

e performance invoking suffering, heroism and constancy was created during the M

arshal Law in Poland. While working on their next project Carmina Burana (1990),

which centred on the myth of Tristan and Isolde, the company went abroad to stu

dy Celtic themes and medieval music.

In 1996 Staniewski composed his last performance, "a theatrical essay" based on

the only Latin novel, which survived in its entirety, Metamorphoses or Golden As

s by Apuleius, a second century writer and orator. Staniewski attempted to revit

alise not only an ancient myth but also ancient Greek music. Tomasz Rodowicz, th

e main actor in Gardzienice, explains: "The work on Metamorphoses proceeded on t

wo independent levels for many months. The first level conducted by Włodzimierz St

aniewski was connected with Apuleius and Plato, looking for references to our Ex

peditions, studies of ancient iconography and the creation of new actors' techni

que. The second level conducted by a professional musician Maciej Rychły was an at

tempt to enter the world of ancient Greek music. He wanted us to read ancient mu

sic through the rhythms of the Balkans or Peloponnesian Peninsula. Singing Greek

hymns like Balkan ones (3+3+2+2) we felt in our bodies that these rhythms have

a power of flywheels".

With equal intensity Rychły studied both the scraps of ancient manuscripts with mu

sic and the paintings preserved on vases. He tried to enliven each dancing gestu

re frozen on the vases and to apply to this movement the best suiting musical fr

agment. So, for hours he had been dancing and singing in order to bring about hi

s own body experience. Later he passed on his discoveries directly into the acto

rs' bodies and voices. At the crucial stages the process was verified by Staniew

ski who incorporated chosen materials into the final performance. During the wor

k on Metamorphoses Gardzienice closely collaborated with classical scholars in P

oland. Regardless of the academic value of their reconstruction they probably su

cceeded in bringing back to life the spirit of ancient Greek music and dance. We

couldn't ask for more.

In his musically structured performances Staniewski has always attempted to embo

dy the idea of the Expedition culminating in the Gathering and to bring about th

e meeting of "high culture" with the "low culture". One year ago an American sch

olar Richard Schechner accused Gardzienice of neo-colonialism and escapism. I wo

uld argue, however, that the opposite is true. Staniewski's work has always been

a testimony to the complex structure of Polish society, something which the com

munist rulers tried to deny by perpetuating in their official propaganda a visio

n of a homogeneous and a unified nation. In his early performances he gave a voi

ce to the ethnic minorities who were not only ignored and silenced but for a sho

rt time after the Second World War also persecuted and exterminated by the Polis

h government. Even in the very "archaeological" and elaborated Metamorphoses the

actors behave like simple villagers who still remember how to sing their tradit

ional songs. Only this time these songs belong to the heritage of the ancient Gr

eece.

Conclusion: In search for a definition

The focus of my presentation was the performative power of myth. Kantor, Grotows

ki and Staniewski proved with their art and lives that myths have certain basic

structures and potentialities which allow for different retellings, interpretati

ons and applications. Kantor internalised myth to construct his own identity, Gr

otowski used myth to redefine and restructure the identity of his community, and

for Staniewski myth became a vehicle to enliven ancient artistic procedures and

empower people living in the rural province. No generally accepted definition o

f myth exists. The best approximation was given by Walter Burkert (born in 1931)

, one of the main scholars of ancient Greek Religion, a Professor of Classics at

the university of Zurich. In his 1979 book, Structure and History in Greek Myth

ology and Ritual, Burkert wrote: "myth is a traditional tale with secondary, par

tial reference to something of collective importance".

The word "traditional" implies a story which cannot be connected to any first st

oryteller known by a name. In the context of oral culture at least, there was no

t a fixed narration which was passed on but different plots associated with diff

erent performers. Polish artists can be counted among them. They contributed to

preserving ancient myths by re-enacting their basic patterns and merging them wi

th their own stories which, in a mysterious turn, acquired a collective importan

ce.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Order of Magnitude-2017Document6 pagesOrder of Magnitude-2017anon_865386332No ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Polymeric Nanoparticles - Recent Development in Synthesis and Application-2016Document19 pagesPolymeric Nanoparticles - Recent Development in Synthesis and Application-2016alex robayoNo ratings yet

- Organizational Behavior (Perception & Individual Decision Making)Document23 pagesOrganizational Behavior (Perception & Individual Decision Making)Irfan ur RehmanNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Outline - Criminal Law - RamirezDocument28 pagesOutline - Criminal Law - RamirezgiannaNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- International Gustav-Bumcke-Competition Berlin / July 25th - August 1st 2021Document5 pagesInternational Gustav-Bumcke-Competition Berlin / July 25th - August 1st 2021Raul CuarteroNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- DLP No. 10 - Literary and Academic WritingDocument2 pagesDLP No. 10 - Literary and Academic WritingPam Lordan83% (12)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- 23 East 4Th Street NEW YORK, NY 10003 Orchard Enterprises Ny, IncDocument2 pages23 East 4Th Street NEW YORK, NY 10003 Orchard Enterprises Ny, IncPamelaNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- EDCA PresentationDocument31 pagesEDCA PresentationToche DoceNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

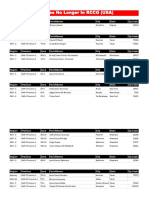

- Churches That Have Left RCCG 0722 PDFDocument2 pagesChurches That Have Left RCCG 0722 PDFKadiri JohnNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Caregiving Learning Activity Sheet 3Document6 pagesCaregiving Learning Activity Sheet 3Juvy Lyn CondaNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- SEW Products OverviewDocument24 pagesSEW Products OverviewSerdar Aksoy100% (1)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- BRAC BrochureDocument2 pagesBRAC BrochureKristin SoukupNo ratings yet

- Medicidefamilie 2011Document6 pagesMedicidefamilie 2011Mesaros AlexandruNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Performance MeasurementDocument13 pagesPerformance MeasurementAmara PrabasariNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- HTTP Parameter PollutionDocument45 pagesHTTP Parameter PollutionSpyDr ByTeNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Samsung LE26A457Document64 pagesSamsung LE26A457logik.huNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Reflection On Sumilao CaseDocument3 pagesReflection On Sumilao CaseGyrsyl Jaisa GuerreroNo ratings yet

- BirdLife South Africa Checklist of Birds 2023 ExcelDocument96 pagesBirdLife South Africa Checklist of Birds 2023 ExcelAkash AnandrajNo ratings yet

- DLL LayoutDocument4 pagesDLL LayoutMarife GuadalupeNo ratings yet

- Test 1Document9 pagesTest 1thu trầnNo ratings yet

- Final ReflectionDocument4 pagesFinal Reflectionapi-314231777No ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- 15.597 B CAT en AccessoriesDocument60 pages15.597 B CAT en AccessoriesMohamed Choukri Azzoula100% (1)

- Sayyid DynastyDocument19 pagesSayyid DynastyAdnanNo ratings yet

- Formal Letter Format Sample To Whom It May ConcernDocument6 pagesFormal Letter Format Sample To Whom It May Concernoyutlormd100% (1)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Deadlands - Dime Novel 02 - Independence Day PDFDocument35 pagesDeadlands - Dime Novel 02 - Independence Day PDFDavid CastelliNo ratings yet

- Volvo D16 Engine Family: SpecificationsDocument3 pagesVolvo D16 Engine Family: SpecificationsJicheng PiaoNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Philosophy of The Human Person: Presented By: Mr. Melvin J. Reyes, LPTDocument27 pagesIntroduction To Philosophy of The Human Person: Presented By: Mr. Melvin J. Reyes, LPTMelvin J. Reyes100% (2)

- Michael M. Lombardo, Robert W. Eichinger - Preventing Derailmet - What To Do Before It's Too Late (Technical Report Series - No. 138g) - Center For Creative Leadership (1989)Document55 pagesMichael M. Lombardo, Robert W. Eichinger - Preventing Derailmet - What To Do Before It's Too Late (Technical Report Series - No. 138g) - Center For Creative Leadership (1989)Sosa VelazquezNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- Berrinba East State School OSHC Final ITO For Schools Final 2016Document24 pagesBerrinba East State School OSHC Final ITO For Schools Final 2016hieuntx93No ratings yet

- Steven SheaDocument1 pageSteven Sheaapi-345674935No ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)