Professional Documents

Culture Documents

,DanaInfo Proquest Umi Com+out

Uploaded by

nirmalarothinamOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

,DanaInfo Proquest Umi Com+out

Uploaded by

nirmalarothinamCopyright:

Available Formats

www.ccsenet.org/elt English Language Teaching Vol. 3, No.

4; December 2010

An Empirical Study of the Role of Output in Promoting the Acquisition

of Linguistic Forms

Zhaojuan Song

School of Translation and Interpretation, Qufu Normal University Rizhao Campus

80 Yantai Road, Rizhao, Shandong 276826, China

E-mail:zhaojuansong@163.com

Abstract

This study examines the effectiveness of an output practice, i.e., Chinese-to-English translation, on promoting

noticing and acquisition of a type of grammatical form, i.e., lexical phrases. It is confirmed that output is vital in

facilitating learners’ noticing and acquisition of the targeted linguistic forms.

Keywords: Output, Noticing, Linguistic forms, Acquisition

1. Introduction

Researches have been studying for the effective ways to improve English learners’ language ability. The role of

output in second language learning has attracted great interests of researchers and scholars since Swain put forward

her Output Hypothesis in 1985.

Swain (1995) argues that, under certain circumstances, output may stimulate noticing of the target linguistic forms

contained in the subsequently provided input, and finally results in the acquisition of the target forms.

In teaching English as a foreign language in China, to improve learners’ output ability (i.e. speaking and writing in

English) is an important aspect. However, output practice has not been given sufficient weight in relation to input

practice. Even if the Communicative Language Teaching (CLT) has been taken as one important approach in

China’s classroom teaching, of which negotiated meaning is the primary focus, learners demonstrate weaknesses in

grammatical accuracy and collocation appropriateness in speaking and writing, despite gaining high-level

communicative fluency. So it is still necessary to think about the role of output in the acquisition of linguistic forms.

Based on the output hypothesis, this thesis attempts to make an empirical study of the effects of output on promoting

noticing and learning target linguistic forms. Specifically, this study will examine the effectiveness of an output

practice, i.e., Chinese-to-English translation, on promoting noticing and acquisition of a type of grammatical form,

i.e., lexical phrases, hoping that the results of this study will provide some support for the noticing function of

output proposed by Swain and important pedagogical implications for China’s English teaching.

2. Theoretical rationales and an overview of related studies

2.1 The role and studies of noticing

Schmidt (1990, 1994) has proposed the Noticing Hypothesis, which claims that “noticing is the necessary and

sufficient condition for the conversion of input to intake for learning” (1994, p. 17). Schmidt’s theories emphasize

the role of noticing in promoting interlanguage development.

If noticing is necessary in learning linguistic form, the question then arises of how noticing takes place. Schmidt

(1990) proposes that frequency of a form, perceptual salience, instruction, the current state of learners’ interlanguage,

and task demands all play an important role in directing attention and bringing some features of input into

awareness.

To sum up, the results of these studies suggest that drawing learners’ attention to form by various ways facilitates

their L2 learning. Learners whose attention is deliberately drawn to the targeted language forms via external input or

task manipulation tend to demonstrate more accurate use of language forms.

2.2 The role and studies of output

Schmidt and Frota (1986) argue that “a second language learner will begin to acquire the target-like form if and only

it is present in comprehensible input and ‘noticed’ in the normal sense of the word, that is consciously” (p. 311).

Swain proposes in her output hypothesis that output can facilitate the process of noticing of both problems in one’s

IL and the relevant features in the input. This noticing will then stimulate the processes of language acquisition by

prompting learners to seek out relevant input with more focused attention (Swain & Lapkin, 1995).

The results of studies done by Izumi et al. (1999, 2000) demonstrate no unique effects of output, but suggest

Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education 109

www.ccsenet.org/elt English Language Teaching Vol. 3, No. 4; December 2010

opportunities to produce output and receive relevant input are vital in improving the use of the target structure.

Since Swain put forward the Output Hypothesis, some researchers and teachers in China are interested in it. They

constantly publish articles to introduce this theory to the Chinese English learners. But the earlier studies mostly are

the introduction of this theory and of correlative studies abroad to investigate the effectiveness of output in SLA, and

the discussion of the roles of input and output and its inspiration to China’s foreign language teaching, for example,

Lu Renshun (2002), Zheng Yinfang (2003). Unfortunately, experimental studies on the influence of

production-based instruction on learners’ production abilities are comparatively few. Niu Qiang (2002) put forward

the strategy of raising the learners’ consciousness to production level. The research done by Wang Chuming (2000)

shows that composition-writing can improve learners’ English production ability. The study by Feng Jiyuan and

Huang Jiao (2004) is designed to measure the effectiveness of output practice in helping learners acquire linguistic

forms, which closely follows the experimental procedure of the studies done by Izumi (2000), making only few

modification. The findings of this study are consistent with those of Izumi et al. (2000).

To further explore the utility of output in promoting noticing and SLA, future research needs to examine the effects

of noticing on other grammatical forms under varying conditions. So the present study will examine the

effectiveness of a different output practice, i.e., translation, on promoting noticing and acquisition of a different

grammatical form, i.e., lexical phrases. The participants are the college English learners under EFL situation in

China.

3. Research method

3.1 Participants

The second-year students from Foreign Language College of Qufu Normal University were the participants of this

study (N=36). We randomly sampled thirty-six students from two parallel classes of equal level. After the

administration of the pretest, the participants were ranked according to their pretest scores and divided into two

groups, i.e., the experimental group (EG, n=18) and the control group (CG, n=18), composed of students at

approximately equivalent levels. This procedure was employed to ensure that each group contained an adequate

representation of students with different initial knowledge of the target structure (Izumi et al. 2000).

3.2 Target Form

The lexical phrases were the target form in this study. The term “lexical phrases” is adopted here to mean

“multi-word lexical phenomena…which are conventionalized form/function composites that occur more frequently

and have more idiomatically determined meaning than the language that is put together each time” (Nattinger &

DeCarrico 1992:1).

Much of human language is formulaic. Through interaction, English learners will pick up many formulaic sequences

native people use in their everyday life, e.g., “it doesn’t matter.” and “it’s very kind of you.” But sometimes English

learners will ignore these prefabricated chunks of language, and usually they will focus on discrete isolated words,

as are found in vocabulary lists. Many students in China indeed work hard to memorize long vocabulary lists.

However, since these words are learned in isolation, they do not necessarily help make their L2 idiomatic.

Low-proficiency Chinese students of English, for instance, often produce forms like

* Jack is married with Mary. or * Jack marries with Mary.

They have to notice the formulaic pattern “A is married to B” and remember it before they are able to produce the

correct form.

The pretest results confirmed this observation. Some representative sentences produced by the participants of both

groups are shown below.

The diseases which caused by smoking are under enquiry.

The group decided to undertake a civil disobedience campaign named for freedom and justice.

They could reproduce naturally, but resign to the risk of passing on the disease to their child.

From those examples we can say that participants from both groups were not unfamiliar with the main words of the

target phrases, but they did not know the collocation of them and could not use them freely and appropriately.

3.3 Research design

The whole process of the research lasted four weeks. And the experimental sequence of the study took

approximately 3 hours. The experiment consisted of one pretest, the treatment and one posttest. In order to obtain

some information about what kinds of problems our participants had while producing output and what they paid

attention to while processing input, we also conducted a brief interview with some randomly selected

110 ISSN 1916-4742 E-ISSN 1916-4750

www.ccsenet.org/elt English Language Teaching Vol. 3, No. 4; December 2010

experimental-group participants after the task. All the subjects took part in two tests, i.e., pretest, and posttest. By

pretest, it was intended to get to know the participants’ initial knowledge of the target forms that were going to be

taught and whether they had acquired them or not. By posttest, we can get to know whether the participants had

acquired the target forms as we had expected.

3.3.1 Research procedure

Before the experiment, the researcher informed the subjects of the whole process of the experiment in detail. Before

subjects carried out the tasks, the underlining portion of the activity was modeled for both groups. In order to assess

noticing of the target form, subjects were required to underline the passage when they were provided with the input.

The experimental group participants were directed to underline “sequences of words” that they felt were particularly

necessary for their subsequent tasks (i.e., translation). The control group was also required to underline their passage

for comprehension (i.e., to answer questions about the passage). The researcher, using a passage that did not contain

the target form, showed participants examples of underling, to illustrate the options of underlining the “sequences of

words” of the passage and to stress the importance of precise underlines. This was done to enhance subjects’

familiarity with the underlining procedure and the precision of this measurement of noticing. Because underling was

assumed to involve at least a minimum level of awareness, we believe that it tapped noticing in Schmidt’s sense

(Izumi et al.2000).

All the participants took part in the pretest the first week. In an attempt to minimize the test effects, the treatment

began a week after the pretest. Two weeks later, this treatment was followed by the posttest in order to examine the

effectiveness of learning.

3.3.2 Treatment

EG participants were asked to translate some Chinese sentences into English. And the CG was asked to answer some

comprehension questions related to the input. Each group completed the tasks in a separate classroom. The

procedure is as follows:

EG read carefully about the translation directions. And five minutes later, they began to translate. They were given

some Chinese sentences, and were asked to translate each sentence using the expression containing the given words

(20 min.). The CG read a passage as a reading material and answered some comprehension questions about it.

Twenty minutes later, the teacher collected their translation and presented the model essay in which there were the

native-like usages of the given words. The essay was provided as a reading exercise for the CG. Participants read

and underlined this input (30 min for the EG and 30 min for the CG). After the input passage was collected, the EG

subjects were then asked to produce a second version of the translation, incorporating whatever they had learned

from the model essay. CG subjects answered some comprehension questions related to the essay. We expected that

the participants would notice problems with their language when producing output and that subsequent exposure to

the target-like input would help the participants to compare their interlanguage production with the target-like usage

of it in that input.

3.3.3 Interview

Questions asked of the participants in interview are the following: (a) What did you underline while reading the

passage? And why did you underline it? (b) Describe all difficulties or problems you had in producing the output the

first time. (c) What did you try to do differently when you did the translation the second time?

3.3.4 Testing instruments

In this study, two written test methods were used to assess the participants’ knowledge of the target lexical phrases: a

multiple-choice recognition test, and Chinese-English translation.

In pretest, two methods were used to test participants’ knowledge of the target phrases. In the recognition part, six

sentences were given, each containing an underlined target form. The participants were asked to choose one

explanation that best illustrated each target form. In the translation part, participants were asked to translate five

sentences using the given words. The pretest lasted 25 minutes.

In the output practice during the treatment, only one test item was used, i.e., Chinese-English translation. The EG

was given eight Chinese sentences and was asked to translate them into English using the expressions containing the

given words. The translation practice lasted 25 minutes.

We use the pretest as the posttest in order to compare the two different scores made by the participants.

3.3.5 Scoring and analysis

The data consists of the participants’ underling made during the treatment and written productions produced during

Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education 111

www.ccsenet.org/elt English Language Teaching Vol. 3, No. 4; December 2010

the treatment and tests. The following is a description of how each data set is analyzed.

Underlining scoring. For each participant, we counted all items underlined and calculated the percentage of target

lexical phrases underlined out of this total. This procedure was used to balance individual variation arising from

differences in the absolute quantity of underling by the participants. For the purpose of this study, underlined

isolated word would not get the point, except the whole phrase including the main word of the phrase and its

collocation. In this sense, if these words were underlined, we took it as an indication of the participants’ paying

attention to the lexical phrases.

Production scoring. The production scores obtained for the EG from the treatment were analyzed to examine

whether the form noticed during the exposure to the input would be incorporated into the participants’ second

production attempts. This was called the immediate incorporation stage. The data obtained from tests were used to

examine whether the treatment resulted in the acquisition of the target form.

The recognition test items were scored as either correct or incorrect. If it was correct, we gave 1 point for it. If it was

incorrect, it would get zero. The production test was scored like this: We gave 1 point for each target-like production.

If the collocation was not appropriate, we would not give the point. Incorrect morphology (e.g., threaten for threat)

was taken to be correct for the purpose of this study.

Statistical procedures. We use mean ( x ) as a measure of central tendency and standard deviation (S.D.) as a way of

variability in all the results reported. The mean is the sum of all scores of all subjects in a group divided by the

number of subjects, which provides information on the average behavior of the subjects on certain tasks. The

standard deviation is the square root of the averaged square distance of the scores from the mean. The higher the

standard deviation, the more varied and more heterogeneous a group is on a given behavior. Because there are only

two groups in the experiment, i.e., experimental group and control group, we will use the t-test to calculate the

significance of the results. The t-test is used to compare the means of two groups. It helps determine how confident

the researcher can be that the differences found between two groups (experimental and control) as a result of

treatment are not due to chance.

A slightly different t-test formula, paired t-test, was applied when the comparison was between the same group

compared at two different times (such as pretest and posttest, and task results in the treatment respectively obtained

before and after the input provided). It helps determine the differences found between the same group at different

times are significant.

4. Results and discussion

4.1 Results

4.1.1 Results of underlining: the noticing issue

In the treatment, the EG was asked to do output practice while the CG did the comprehension exercise. After that,

the EG received the input passage as a model essay to be learned from (with what was to be learned left entirely up

to each learner) whereas the CG received the same passage as a reading comprehension exercise. And then they

were asked to underline the phrases that they thought were especially useful for their tasks. Therefore, our interest

here was in whether the EG and the CG differed with respect to their noticing of phrase-related words, as well as

whether the EG paid more attention to the target phrases. The standard deviation (S.D.) showed that the individual

variation within the EG was smaller than that of the CG. The mean underline score of the experimental group

(87.11%) is higher than that of the control group (52.11%). And the differences between the EG and the CG were

statistically significant (p=.000<.05). The t-value was significant at the .05 level. Therefore, we can argue that

output may promote noticing on the relevant input.

4.1.2 Task results: the immediate uptake issue

The results of the production (translation) by the EG during the treatment was the EG participants showed virtually

little target-like use of the lexical phrases in their first version of translation. The mean percentage of the correct

usage of lexical phrases increased from 28.0556 to 74.7778. And the differences between the experimental group at

the two different times were statistically significant (p=.000<.05). These results indicated that there was an

immediate incorporation of the target form by the EG in the output practice.

4.1.3 Test results: the acquisition issue

4.1.3.1 Results of multiple-choice recognition test

The experimental participants’ mean score on the multiple-choice recognition test increased from the pretest (3.1667;

of 6 questions) to the posttest (4.7778; of 6 questions). We then used the paired t-test to examine the significance of

the differences between scores on pretest and on posttest. The increase in the score from the pretest to the posttest

112 ISSN 1916-4742 E-ISSN 1916-4750

www.ccsenet.org/elt English Language Teaching Vol. 3, No. 4; December 2010

was statistically significant (p=.000<.05). For the control group, the mean score increased from 3.7778 to 4.3333.

The results of paired t-test indicated that the comparison of the pretest mean score and the mean score on the posttest

revealed insignificant differences (p=.066>.05).

For between-group comparisons, the differences between the experimental participants’ mean score on the pretest

and the CG’s score (3.78) on the pretest was statistically significant (p=.022<.05), while the comparison of the EG’

mean score (4.78) on the posttest and that of CG (4.34) did not reveal significant differences (p=.198>.05). These

results indicated that the differences between the effectiveness of the two different tasks (i.e., translation; reading

comprehension) on promoting understanding of lexical phrases were not significant.

4.1.3.2 Results of translation test

The EG’ mean percentage of the correctly formulated sentences on the pretest (4%) was very low, as well as the

CG’s (4%), although both of them did fairly well on the multiple-choice recognition part in the pretest. These results

indicate that both the experimental group and the control group were not familiar with the lexical phrases that were

to be learned. And they could not produce the sentences with the given words correctly, although they could identify

the meanings of some lexical phrases from the context. However, the experimental group scored a high mean

percentage on the posttest (M=86%). And the improvement was statistically significant from the pretest to the

posttest (p=.000<.05). For the CG, there was also an increase from the pretest (4%) to the posttest (44%). And the

difference between the pretest and the posttest was also statistically significant (p=.000<.05). Here arose a question:

Since both the improvements of the two groups from pretest to posttest were statistically significant, did it indicate

that the effect of output on promoting acquisition was the same as that of the input practice?

The EG’s mean percentage of correctly formulated sentences was 86%, while the CG’s was 44%. The t-test was

used to examine whether the difference between the mean posttest scores obtained by the experimental participants

and by the control group was significant. The t-test results indicated that the difference between the two groups was

significant (p=.000<.05). And these results indicated that the EG made significantly larger gains than did the CG and

that the effect of output practice on promoting acquisition of lexical phrases was much greater than that of input

practice.

4.2 Discussion

To summarize the major findings of this study, the first finding showed greater noticing of the target form for the EG

than the CG. The unique effects of output in promoting noticing of the form therefore were confirmed in this study.

The second one was that the EG would indicate immediate uptake of the target form in their output during the

treatment tasks, which was confirmed in that the EG participants showed a significant improvement in their accurate

use of the target form from the first production to the second production during the treatment. The analysis of the

scores of the two groups on the posttest revealed that the difference between the two groups on the posttest was

significant. So the third finding was that the EG would show greater acquisition of the lexical phrases.

It was an unexpected result that not only the EG but also the CG showed significant increases in multiple-choice

recognition test items from pretest to posttest. It indicated that the CG can understand the lexical phrases fairly well

although they cannot achieve native-like usage of them. Swain argues that it is possible to comprehend input—to get

the message—without a syntactic analysis of that input (Swain, 1985, p.249). This could explain the phenomenon in

this study that the CG can understand the lexical phrases and yet can only produce few correct sentences. They had

just never gotten to a syntactic analysis of the phrases because there had been no demand on them in the tasks to

produce output with these phrases. So they did not really grasp the grammatical rules of these phrases. This just can,

from a different angle, best illustrate the noticing function of output which claims that “producing the target

language may be the trigger that forces the learner to pay attention to the means of expression needed in order to

successfully convey his or her intended meaning” (Swain, 1995). On the other hand, our interview with the EG

participants after the treatment also provided partial support for the noticing function of output, as 95% interviewed

participants claimed that most of their underlines were the phrases which they were required to use while doing the

translation.

5. Summary

This study basically confirmed Swain’s output hypothesis. Specifically, it provided partial support for the noticing

function of output and made some contributions to studies in SLA which are mainly interested in the role of output

in promoting second language acquisition. Undoubtedly, the findings of this study had important pedagogical

implications for English teaching in China. However, there were some problems, unavoidably. To further explore the

utility of output in promoting noticing and SLA, further research needs to examine the effects of noticing on other

grammatical forms under varying conditions. Further investigation will help specify the conditions under which

Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education 113

www.ccsenet.org/elt English Language Teaching Vol. 3, No. 4; December 2010

output, in combination with input can most effectively promote SLA, an important issue for both theory construction

and pedagogic applications.

References

Brown, H. D. (2002). Principles of Language Learning and Teaching. Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and

Research Press.

Ellis, R. (1994). The Study of Second Language Acquisition. Oxford: OUP.

Feng, J. & Huang. J. (2004). The Effect of Output Tasks on Acquisition of Linguistic Forms. Modern Foreign

Languages 2: 195-200.

Hughes, A. (2000). Testing for Language Teachers. Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press.

Izumi, S., Bigelow, M., Fujiwara, M., & Fearnow, S. (1999). Testing the output hypothesis: Effects of output on

noticing and second language acquisition. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 21: 421-452.

Izumi, S. & Bigelow, M. (2000). Does output promote noticing and second language acquisition. TESOL Quarterly

34: 2, 239-278.

Lu, R. (2002). The Output Hypothesis and Its Implications for China’s English Teaching. Foreign Languages and

Their Teaching 4: 34-37.

Nattinger, J. & DeCarrico, J. (1992). Lexical Phrases and Language Teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Niu, Q. (2002). On Combining Comprehension and Production in SLA. Foreign Language World 1: 56-62.

Schmidt, R. & Frota, S. (1986). Developing basic conversational ability in a second language: a case-study of an

adult learner. In R. Day (Ed.), Talking to Learn. Rowley, Mass.: Newbury House.

Schmidt, R. 1990. The role of consciousness in second language learning. Applied Linguistics 11:129-158.

Schmidt, R. (1994). Deconstructing consciousness: in search of useful definitions for Applied Linguistics. AILA

Review 11:11-26.

Skehan, P. (1998). A Cognitive Approach to Language Learning. Oxford: OUP.

Swain, M. (1985). Communicative competence: some roles of comprehensible input and comprehensible output in

its development. In S. Gass and C. Madden (eds.), Input in Second Language Acquisition. Rowley, MA: Newbury

House. 235-253.

Swain, M. (1995). Three Functions of Output in Second Language Learning. In G.. Cook and B. Seidlhofer (Eds.),

Principles and Practice in Applied Linguistics (125-144). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Swain, M. & Lapkin, S. (1995). Problems in output and the cognitive processes they generate: A step towards

second language learning. Applied linguistics 16: 371-391.

Wang, C., Niu, R. & Zheng, X. (2000). Improving English through Writing. Foreign Language Teaching and

Research 3: 207-212.

Zheng, Y. (2003). A Review of Input and Output in Second Language Acquisition. Journal of Guangzhou

University (Social Science Edition) 2:67-69.

114 ISSN 1916-4742 E-ISSN 1916-4750

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

You might also like

- Classroom Interaction and Language OutputDocument12 pagesClassroom Interaction and Language OutputdrtaroutiNo ratings yet

- Teaching and Learning English Verb Tenses in A Taiwanese UniversityDocument17 pagesTeaching and Learning English Verb Tenses in A Taiwanese UniversityNhatran93No ratings yet

- Ikhwan - Shafwan - P - Tbi 5D - Final Test Research EltDocument6 pagesIkhwan - Shafwan - P - Tbi 5D - Final Test Research EltGono UmanailoNo ratings yet

- Corrective Feedback On Acquisiton of Chinese DCDocument12 pagesCorrective Feedback On Acquisiton of Chinese DCMoazzam Ali khanNo ratings yet

- RELP - Volume 6 - Issue 1 - Pages 39-55PRETEST POSTTEST PDFDocument17 pagesRELP - Volume 6 - Issue 1 - Pages 39-55PRETEST POSTTEST PDFTrần ĐãNo ratings yet

- The Role of Output & Feedback in Second Language Acquisition: A Classroom-Based Study of Grammar Acquisition by Adult English Language LearnersDocument21 pagesThe Role of Output & Feedback in Second Language Acquisition: A Classroom-Based Study of Grammar Acquisition by Adult English Language LearnersLê Anh KhoaNo ratings yet

- A Research Plan Fulfilled For Second Language Acquisition Lecture Lecturer: Dian Misesani, S.S., M.PDDocument6 pagesA Research Plan Fulfilled For Second Language Acquisition Lecture Lecturer: Dian Misesani, S.S., M.PDChildis MaryantiNo ratings yet

- Self-Assessment, Noticing, and EFL Oral AbilityDocument34 pagesSelf-Assessment, Noticing, and EFL Oral AbilityChristine YangNo ratings yet

- An Empirical Study of Pragmatic Input To Chinese EFL LearnersDocument11 pagesAn Empirical Study of Pragmatic Input To Chinese EFL LearnersFung LeoNo ratings yet

- DeSteffen 2015Document8 pagesDeSteffen 2015Anonymous 8jEiA8EMDNo ratings yet

- Proposal The Correlation Beetwen Listening Song and Vocabulary MasteryDocument9 pagesProposal The Correlation Beetwen Listening Song and Vocabulary MasteryOpikNo ratings yet

- Mini Skripsi Chapter I II IIIDocument19 pagesMini Skripsi Chapter I II IIINyayu KhoirunnisaNo ratings yet

- Motivation and Autonomy in Learning English As Foreign Language: A Case Study of Ecuadorian College StudentsDocument14 pagesMotivation and Autonomy in Learning English As Foreign Language: A Case Study of Ecuadorian College StudentsNoor JomaaNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Accent(s) and Pronunciations(s) of English On Bangladeshi English Language Learners' Listening Skill Acquisition ProcessDocument9 pagesThe Effect of Accent(s) and Pronunciations(s) of English On Bangladeshi English Language Learners' Listening Skill Acquisition ProcessMiriam LopezNo ratings yet

- The Asian EFL Journal March 2020 Volume 24, Issue 2: Senior Editors: Paul Robertson and John AdamsonDocument170 pagesThe Asian EFL Journal March 2020 Volume 24, Issue 2: Senior Editors: Paul Robertson and John Adamsonspjalt2020No ratings yet

- The Effect of Teaching Vocabulary Through The Diglot - Weave Technique and Attitude Towards This TechniqueDocument6 pagesThe Effect of Teaching Vocabulary Through The Diglot - Weave Technique and Attitude Towards This TechniqueDr. Azadeh NematiNo ratings yet

- Understanding English Speaking Difficulties An Investigation of Two Chinese PopulationsDocument19 pagesUnderstanding English Speaking Difficulties An Investigation of Two Chinese Populationsgongchuchu1No ratings yet

- FULLTEXT01Document27 pagesFULLTEXT01Muhammad AkramNo ratings yet

- Article 05Document24 pagesArticle 05Minh Thành DươngNo ratings yet

- GamifiedDocument3 pagesGamifiedJohn Earl ArcayenaNo ratings yet

- Final Research PaperDocument29 pagesFinal Research PaperIsabela CuestaNo ratings yet

- Review of Related Literature The Influence of Students' Achievement in Vocabulary To Reading AbilityDocument19 pagesReview of Related Literature The Influence of Students' Achievement in Vocabulary To Reading AbilityPoni MoribNo ratings yet

- 5946-Article Text-28455-1-10-20220601Document7 pages5946-Article Text-28455-1-10-20220601Vela LaveNo ratings yet

- Concept PaperDocument6 pagesConcept PaperJessaMae AlbaracinNo ratings yet

- A Case Study at The Ten Grade of A State Vocational High School in CiamisDocument10 pagesA Case Study at The Ten Grade of A State Vocational High School in CiamisAnonymous HHSZYT6XNo ratings yet

- Chapter IDocument7 pagesChapter IDian Eunhyukkie Si JutekNo ratings yet

- Draft of Annotated Bibliography Fairatul Husna Daslin (16018052)Document9 pagesDraft of Annotated Bibliography Fairatul Husna Daslin (16018052)annisadaslinNo ratings yet

- Ficha BibliográficaDocument12 pagesFicha BibliográficaDavid Stivens Castro SuarezNo ratings yet

- Classroom Interaction and Language... 165Document23 pagesClassroom Interaction and Language... 165Bachir TounsiNo ratings yet

- Scopus - The Effectiveness of Independent Learning Method On StudentsÔÇÖ Speaking Achievement at Christian University of Indonesia JakartaDocument13 pagesScopus - The Effectiveness of Independent Learning Method On StudentsÔÇÖ Speaking Achievement at Christian University of Indonesia JakartaAbdal Khair KhusyairiNo ratings yet

- Teacher Talk and Student Talk: Classroom Observation StudiesFrom EverandTeacher Talk and Student Talk: Classroom Observation StudiesNo ratings yet

- Multiple Choice English Grammar Test Items That Aid English Grammar Learning For Students of English As A Foreign LanguageDocument17 pagesMultiple Choice English Grammar Test Items That Aid English Grammar Learning For Students of English As A Foreign LanguageAdalia López PNo ratings yet

- NerizadionioDocument5 pagesNerizadioniobelaNo ratings yet

- A Quantitative Action Research On Promoting ConfidenceDocument21 pagesA Quantitative Action Research On Promoting ConfidenceFiza Joon MblaqNo ratings yet

- 128 13 472 1 10 20170826 PDFDocument30 pages128 13 472 1 10 20170826 PDFPhoebe THian Pik HangNo ratings yet

- Constantino Solmerin Lomboy Pascual ResearchProposal.Document12 pagesConstantino Solmerin Lomboy Pascual ResearchProposal.Jonathan PascualNo ratings yet

- Language Choice in Note-Taking For C-E Consecutive InterpretingDocument11 pagesLanguage Choice in Note-Taking For C-E Consecutive InterpretingHasan Can BıyıkNo ratings yet

- Noticing Grammar in L2 WritingDocument17 pagesNoticing Grammar in L2 WritingRODERICK GEROCHENo ratings yet

- The Effect of Input-Based and Output-Based Instruction On EFL Learners' Autonomy in WritingDocument9 pagesThe Effect of Input-Based and Output-Based Instruction On EFL Learners' Autonomy in WritingTrần ĐãNo ratings yet

- Are You Speaking Comfortably?: Richard Farmer and Elaine SweeneyDocument12 pagesAre You Speaking Comfortably?: Richard Farmer and Elaine SweeneyGeraldine GuardoNo ratings yet

- Module 6 AssignmentDocument4 pagesModule 6 AssignmentMollyNo ratings yet

- 1875 4335 1 PBDocument15 pages1875 4335 1 PBPhương VũNo ratings yet

- Thesis Topics Department of English LinguisticsDocument4 pagesThesis Topics Department of English Linguisticsgjga9bey100% (2)

- Research Paper On Language TeachingDocument4 pagesResearch Paper On Language Teachingfemeowplg100% (1)

- Review of Related LiteratureDocument9 pagesReview of Related LiteratureKenth TanbeldaNo ratings yet

- Development of Oral Communication Skills Abroad: Illinois Wesleyan UniversityDocument25 pagesDevelopment of Oral Communication Skills Abroad: Illinois Wesleyan UniversityMohd FitriNo ratings yet

- How To Teach The Compulsory Essay HandoutDocument13 pagesHow To Teach The Compulsory Essay HandoutSilvina CarrilloNo ratings yet

- Multilingualism and Translanguaging in Chinese Language ClassroomsFrom EverandMultilingualism and Translanguaging in Chinese Language ClassroomsNo ratings yet

- The Effectiveness of Mnemonic Devices For ESL Vocabulary RetentionDocument10 pagesThe Effectiveness of Mnemonic Devices For ESL Vocabulary RetentionPATRICIA TAMAYONo ratings yet

- Focused Vs UnfocusedDocument10 pagesFocused Vs Unfocusedjacobo22No ratings yet

- Analysis of Barriers in Listening CompreDocument7 pagesAnalysis of Barriers in Listening CompreRANDAN SADIQNo ratings yet

- Chapter IDocument8 pagesChapter IYussiNo ratings yet

- EJ1076693Document9 pagesEJ1076693ichikoNo ratings yet

- Engl Teach Read View ComprehensionDocument72 pagesEngl Teach Read View ComprehensionnirmalarothinamNo ratings yet

- Pakistan JORSENDocument10 pagesPakistan JORSENnirmalarothinamNo ratings yet

- Ej 1161157Document14 pagesEj 1161157nirmalarothinamNo ratings yet

- Guidelines: You Send Your Files To Us. Some Documents Require Your Family Name and FirstDocument1 pageGuidelines: You Send Your Files To Us. Some Documents Require Your Family Name and FirstnirmalarothinamNo ratings yet

- Ed 509930Document20 pagesEd 509930nirmalarothinamNo ratings yet

- Handbook of Instructional Research and Instructional TechnologyDocument19 pagesHandbook of Instructional Research and Instructional TechnologynirmalarothinamNo ratings yet

- The School Principal S Role in Teacher Professional DevelopmentDocument18 pagesThe School Principal S Role in Teacher Professional DevelopmentnirmalarothinamNo ratings yet

- A Modest ProposalDocument11 pagesA Modest Proposalnirmalarothinam100% (1)

- Legal Issues in Higher EducationDocument9 pagesLegal Issues in Higher EducationnirmalarothinamNo ratings yet

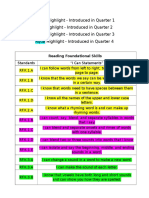

- Outline: Highlights KeywordsDocument1 pageOutline: Highlights KeywordsnirmalarothinamNo ratings yet

- Pekeliling NKRADocument43 pagesPekeliling NKRAYuliamin SahirursahNo ratings yet

- The Impact of School On EFL Learning Motivation: An Indonesian Case StudyDocument24 pagesThe Impact of School On EFL Learning Motivation: An Indonesian Case StudynirmalarothinamNo ratings yet

- Critical Thinking ExerciseDocument2 pagesCritical Thinking ExerciseCarlos TorresNo ratings yet

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- Evaluation of An English Language ProgramDocument128 pagesEvaluation of An English Language Programnirmalarothinam100% (1)

- Study Notes For PMR 80 Days Around The WorldDocument13 pagesStudy Notes For PMR 80 Days Around The WorldnirmalarothinamNo ratings yet

- NCTM AssessmentDocument13 pagesNCTM AssessmentnirmalarothinamNo ratings yet

- IELTS - How To Prepare For WritingDocument22 pagesIELTS - How To Prepare For Writingapi-3829598100% (2)

- AziziyahcippDocument14 pagesAziziyahcippnirmalarothinamNo ratings yet

- Teaching Close Reading of ComprehensionDocument1 pageTeaching Close Reading of ComprehensionnirmalarothinamNo ratings yet

- WB013-2 Sem1 2010-2011Document3 pagesWB013-2 Sem1 2010-2011nirmalarothinamNo ratings yet

- English Sem2Document10 pagesEnglish Sem2nirmalarothinamNo ratings yet

- Sri VidhyaaroopiniDocument1 pageSri VidhyaaroopininirmalarothinamNo ratings yet

- Hindu Astrology 1Document45 pagesHindu Astrology 1api-26502404100% (2)

- English Grammar HandbookDocument135 pagesEnglish Grammar Handbookengmohammad1No ratings yet

- Thir Uch Chir Rambal AmDocument9 pagesThir Uch Chir Rambal AmnirmalarothinamNo ratings yet

- Sri Saneeswara Vasiya ManthramDocument2 pagesSri Saneeswara Vasiya ManthramnirmalarothinamNo ratings yet

- PhaldipikaDocument265 pagesPhaldipikakanishkmechenggNo ratings yet

- Hindu Astrology 1Document45 pagesHindu Astrology 1api-26502404100% (2)

- Guide To Completely Block Ultrasurf in A Mikrotik NetworkDocument6 pagesGuide To Completely Block Ultrasurf in A Mikrotik NetworkPérez Javier FranciscoNo ratings yet

- School - Based Campus JournalismDocument4 pagesSchool - Based Campus JournalismRowena BartolazoNo ratings yet

- Handbook ELE 0910Document52 pagesHandbook ELE 0910NIST Ele ICT DepartmentNo ratings yet

- Following Are Few Tools of AI Used in Businesses: 1. TextioDocument3 pagesFollowing Are Few Tools of AI Used in Businesses: 1. Textioseema gargNo ratings yet

- RTU560 COMPROTware EDocument17 pagesRTU560 COMPROTware Eparizad2500No ratings yet

- Cefr Y1Document6 pagesCefr Y1Mizta DeNo ratings yet

- BSNL LFMT PDFDocument1 pageBSNL LFMT PDFPalakodety Sreenivasa RaoNo ratings yet

- 10 - STUDY GUIDE For COMMUNICATINGDocument10 pages10 - STUDY GUIDE For COMMUNICATINGHeart FerriolNo ratings yet

- Barriers in Learning The English Language of Selected Amt First Year Students of Baao Community College Academic Year 2018-2019Document102 pagesBarriers in Learning The English Language of Selected Amt First Year Students of Baao Community College Academic Year 2018-2019Avegail Mantes100% (1)

- Conclusion Credible - Evidence - Judgment - Relevance-Reliability - Source ValidityDocument4 pagesConclusion Credible - Evidence - Judgment - Relevance-Reliability - Source ValidityArjon Bungay FranciscoNo ratings yet

- 201 0722 QPDocument4 pages201 0722 QPAsyiqin MohdNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document9 pagesChapter 1Jail Bait BrainNo ratings yet

- Nov 2021 P1 MSDocument16 pagesNov 2021 P1 MSShibraj DebNo ratings yet

- FGD Sample.Document3 pagesFGD Sample.Md. YousufNo ratings yet

- Network Interface CardDocument4 pagesNetwork Interface CardKuldeep AttriNo ratings yet

- Role Play Activities Like Character Play' and Situation Building,'Document4 pagesRole Play Activities Like Character Play' and Situation Building,'joseNo ratings yet

- Colin Campbell ResumeDocument1 pageColin Campbell ResumeColin CampbellNo ratings yet

- Thinking Span Trans Ch2Document13 pagesThinking Span Trans Ch2Jamar Armenta GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Switching Basics and Intermediate Routing: CNAP Semester 3Document36 pagesSwitching Basics and Intermediate Routing: CNAP Semester 3Vo Ngoc HoangNo ratings yet

- Black Ships Before Troy: The Story of The Iliad: Extension Project Bloom Ball: A Creative Book ReportDocument3 pagesBlack Ships Before Troy: The Story of The Iliad: Extension Project Bloom Ball: A Creative Book ReportTai D. MatthewsNo ratings yet

- Student Workbook: Network Hardware: GlossaryDocument5 pagesStudent Workbook: Network Hardware: GlossaryJo MamaNo ratings yet

- TwitterDocument13 pagesTwitterKentaroNo ratings yet

- Practice 2Document4 pagesPractice 2chichii01No ratings yet

- Introduction To Media and InformationDocument14 pagesIntroduction To Media and InformationArnel AcojedoNo ratings yet

- Danish DuolingoDocument11 pagesDanish Duolingoandresjensen26No ratings yet

- 5 Building An E-Commerce Presence 2022Document20 pages5 Building An E-Commerce Presence 2022Yomara OktafameroNo ratings yet

- Profile Education: Ahmad BilalDocument2 pagesProfile Education: Ahmad BilalMuhammad Farhan SabirNo ratings yet

- Rpms Table of Contents UMOI LOLIEDocument4 pagesRpms Table of Contents UMOI LOLIEKing CajayonNo ratings yet

- Ela I Can StatementsDocument6 pagesEla I Can Statementsapi-328066245No ratings yet

- An Introduction To Journalism (Demo Teaching)Document13 pagesAn Introduction To Journalism (Demo Teaching)San SanNo ratings yet