Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Ethical Junior: A Typology of Ethical Problems Faced by House Officers

Uploaded by

varun_vashisht49Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Ethical Junior: A Typology of Ethical Problems Faced by House Officers

Uploaded by

varun_vashisht49Copyright:

Available Formats

REVIEW

The ethical junior: a typology of

ethical problems faced by house

officers

Rosalind McDougall1 + Daniel K Sokol2

1

PhD candidate, Centre for Health and Society, 207 Bouverie St, University of Melbourne VIC 3010, Australia

E-mail: r.mcdougall@pgrad.unimelb.edu.au

2

Lecturer, Medical Ethics and Law, Centre for Medical and Healthcare Education, St George’s, University of London,

CranmerTerrace, London SW17 0RE, UK

E-mail: daniel.sokol@talk21.com

Correspondence to: Rosalind McDougall

DECLARATIONS Summary

Although many studies have explored the experiences of doctors in their first postgraduate

Competing interests

year, few have focused on the ethical issues encountered by this group. Based on an extensive

None declared

literature review of research involving house officers, we argue that these doctors encounter a

Funding broad range of ‘everyday’ ethical challenges, from truth-telling to working in non-ideal

None conditions. We propose a typology of house officers’ ethical issues and advocate prioritizing

these issues in undergraduate medical ethics and law curricula.

Ethical approval

Not applicable

Introduction primary concern was to develop a typology of

Guarantor ethical challenges faced by today’s house officers,

RM Although many studies have explored the experi- we chose to focus on recent research. We defined,

ences of doctors in their first postgraduate year,1–3 rather arbitrarily, recent research in this area as

Contributorship few have focused on the ethical issues encountered work published from 1994 onwards.

Both authors by this group. Traditionally called ‘house officers’, To construct the typology, we identified rel-

contributed equally they are now referred to as F1 in the UK and evant publications using three major electronic

‘interns’ in North America and Australia. In this databases: Web of Science, Medline and Philoso-

Acknowledgements

paper, we propose a typology of house officers’ phers’ Index. In Web of Science and Medline, the

The authors thank ethical challenges based on an extensive literature search terms used were ‘intern’ and ‘resident’, con-

the following people review and examine the implications of our classi- structed inclusively (to capture, for example,

for their comments fication for medical training. We adopt a broad ‘internship’). Articles from non-Western settings

on this paper: Susan definition of what counts as an ethical issue. Fol- or published before 1994 were excluded. Searches

Fox, Raanan Gillon, lowing bioethicist Soren Holm, in the context of were also conducted using the term ‘ethics’

Anna Harris, this paper an ethical consideration refers to: together with ‘junior doctor’ and ‘house officer’ to

Dominic Howard and ‘a) a non-legal or not solely legal norm, duty, ensure that relevant literature was not being over-

Tom Smith obligation or right; or b) consequences (well-being, looked due to terminological differences between

happiness etc.) for some specifiable person or groups countries. The search in Philosophers’ Index used

of persons; or c) what kind of person one ought to be the term ‘intern or resident’ (again constructed

or what virtues one ought to have.’4[85] inclusively) together with ‘ethics’ (or ‘ethical’) and

‘medicine’ (or ‘medical’). Much of the literature

did not explicitly aim to investigate ethical issues,

Methodology

but was nonetheless relevant in understanding the

Sociologists, and particularly ethnographers, have ethical challenges faced by house officers.

long been interested in medical internship.5,6

Studies of postgraduate medical training offer fas-

A typology of ethical challenges

cinating insights into the processes of profession-

alization and the moral development of junior The work of Rosenbaum et al. served as the starting

doctors.7,8 As medical education and the organiza- point for our typology.9 Based on in-depth inter-

tion of internships evolve with time and as our views with thirty-one junior doctors in their first,

J R Soc Med 2008: 101: 67–70. DOI 10.1258/jrsm.2007.070412 67

Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine

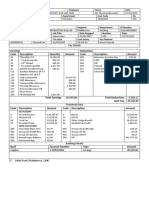

Table 1

A typology of ethical challenges faced by house officers

Type of ethical issue Specific examples

Telling the truth + To patients and relatives about diagnosis and prognosis

+ To patients about lack of experience

+ To consultants about tasks performed

+ To colleagues about a patient’s condition when seeking tests

Respecting patients’ autonomy + Respecting patients’ wishes about treatment, including at the end

of life

+ Maintaining confidentiality

+ Seeking informed consent

Preventing harm + Dealing with potential harm to patients associated with their

treatment

+ Avoiding harm to patients when involving them in the educational

process

Managing the limits of one’s competence + Coping with feeling inadequately prepared for their responsibilities

+ Negotiating lack of supervision/role modelling by superiors

+ Making mistakes

Addressing the inappropriate behaviour of others + Dealing with peers’ mistakes/ incompetence

+ Conflicts between views of junior doctors and superiors –

subjugating own opinions and values to superiors’ demands

+ Observing the unethical behaviour of others

+ Demeaning humour about patients

+ Compromised superiors

+ Superiors handing risky tasks down the hierarchy (‘passing the

buck’)

+ Dealing with verbal or physical abuse by patients or superiors,

including sexual harassment

Conflicts of interest + Ability to treat family and friends

+ Offers of gifts or hospitality from drug companies

Setting interpersonal boundaries with patients + Dealing with sexual advances or romantic intentions

+ Treating disliked, difficult, or dangerous patients

+ Controlling compassion

Impact of working conditions + Dealing with transience

+ Working long hours

+ Feeling unsupported by hospital administration

+ Working when unwell or exhausted

+ Lack of cover for absent colleagues

second or third postgraduate year, these authors categories. For example, making mistakes could

suggested five categories of ethical conflict faced fall under ‘preventing harm’, ‘conflicts of

by junior doctors: interest’ and ‘managing the limits of one’s compe-

tence’. As the typology is derived from existing

(1) concern over telling the truth

research, its scope is limited to aspects of house

(2) respecting patients’ wishes

officers’ experiences that have already been

(3) preventing harm

studied; further ethical issues may emerge as

(4) managing the limits of one’s competence and

more empirical research is conducted with this

(5) addressing performance of others perceived

group.

to be inappropriate.

The brief summaries below elaborate on some

We drew on the literature review to construct a of the issues in Table 1. Since the aim of this paper

more comprehensive typology of the ethical chal- is to present a systematic overview of ethical

lenges faced by house officers. issues, rather than propose solutions to them, we

Table 1 presents eight broad ethical issues, do not attempt to analyse or resolve the problems.

with more specific examples in the second We leave this daunting task to the ethicists and

column. Some of the examples transcend several educators.

68 J R Soc Med 2008: 101: 67–70. DOI 10.1258/jrsm.2007.070412

The ethical junior: a typology of ethical problems faced by house officers

Telling the truth as well as house officers’ fear of verbal abuse or

disapproval.3,13 This could lead to negative out-

Like all doctors, house officers experience truth-

comes for patients, particularly when a house

telling dilemmas. However, their unique position

officer’s limited competence is coupled with inad-

in the medical hierarchy and their dual roles as

equate supervision. The stress experienced by

clinician and learner bring additional problems.

house officers can also be considerable; as newly

Should they tell patients about their lack of experi-

qualified professionals, some feel ill-prepared for

ence? Is it acceptable to stretch the truth with supe-

their responsibilities and struggle to cope.13,16,17

riors to save face? Some house officers deceive

These difficulties can be compounded by the

consultants about figures or tasks they are

absence of role models to serve as moral and prac-

expected to know or perform.10,11[279] In one study,

tical guides.14

14% of participants (doctors in their first, second or

third postgraduate year) indicated that they were

likely to fabricate a laboratory value to a consultant Addressing the inappropriate behaviour

to avoid being humiliated.10 House officers may of others

also lie to colleagues, such as radiographers or

Some house officers will suspect or know that a

laboratory technicians, about a patient’s con-

doctor’s competence is compromised or that a col-

dition in order to obtain tests ordered by a

league’s behaviour is unethical.18 Dealing with this

consultant.11[281–2]

knowledge can be morally distressing, particularly

in the context of house officers’ dependence on

Respecting patient autonomy their superiors for assessment and career advance-

ment. How should house officers handle conflicts

To respect patient autonomy, doctors must pro- between their own beliefs and the views or

vide information without manipulation or coer- demands of their superiors? How should they

cion. In one study, nearly a third of junior doctors behave if they hear colleagues making inappropri-

reported intentionally influencing patients to ate comments about patients?

accept or reject procedures.12 On occasion, junior

doctors struggle to respect patients’ wishes about

treatment: while they may be aware of the Conflicts of interest

patients’ wishes, they may be unable to respect Questions arise about the appropriateness of

them when their superiors are unreceptive to the house officers treating and giving medical advice

patient’s requests.13[59] Finally, house officers can to their friends, their relatives or themselves. There

breach patient confidentiality, often inadvertently, are also moral issues around accepting gifts and

by disclosing information without the patient’s hospitality from drug companies.

permission or by looking at the medical notes of

hospitalized friends or colleagues.12,14

Setting interpersonal boundaries with

patients

Preventing harm

Junior doctors report difficulties around negotiat-

House officers’ duty of non-maleficence (avoiding ing the appropriate level of empathy, compassion

net harm to patients) can be difficult to fulfil when and involvement with their patients. This is per-

involving patients in the educational process. Fur- haps unsurprising given the erosion of compas-

thermore, inexperienced house officers can be dis- sion often associated with medical school

tressed by intrusive procedures and adverse (sometimes referred to in the literature as ‘ethical

patient outcomes, even when the treatment was erosion’).19,20 Issues relating to treating disliked,

necessary and competently performed.9 aggressive or infectious patients and dealing with

patients’ sexual advances or romantic intentions

also fall under this category of ‘boundaries’.21,22

Managing the limits of one’s competence

Many house officers report being asked to perform

Impact of working conditions

tasks which they deem beyond their clinical com-

petence.1,3,15 Some also report difficulties around House officers tend to rotate jobs or placements

accessing support from more senior doctors due to every few months. The lack of stability and the

a variety of factors, including superiors’ work- emphasis on efficiency can contribute to a lack of

loads, absence on leave or unwillingness to assist, reflection and empathy, and an undue deference to

J R Soc Med 2008: 101: 67–70. DOI 10.1258/jrsm.2007.070412 69

Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine

authority.23 Transience also has a negative impact 3 Goldacre MJ, Davidson JM, Lambert TW. Doctors’ view of

their first year of medical work and postgraduate training

on house officers’ personal lives, creating social

in the UK: questionnaire surveys. Med Educ 2003;37:802–8

isolation and making it difficult to pursue interests 4 Holm S. Ethical problems in clinical practice: The ethical

outside medicine. Furthermore, the long working reasoning of health care professionals. Manchester:

hours, although more reasonable than in times Manchester University Press, 1997

5 Mumford E. Interns: From Students to Physicians.

past, can adversely affect their personal lives and, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1970

in turn, patient care. Some junior doctors feel 6 Miller SJ. Prescription for Leadership: Training for the

unsupported by hospital administration.3,24 They Medical Elite. Chicago: Aldine, 1970

7 Bosk C. Forgive and Remember: Managing Medical Failure.

feel dissatisfied with arrangements for covering 2nd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003

absent or sick colleagues. House officers may thus 8 Cassell J. Life and Death in Intensive Care. Philadelphia:

feel obliged to work even when unwell, with Temple University Press, 2005

potentially negative consequences for their own 9 Rosenbaum JR, Bradley EH, Holmboe ES, Farrell MH,

Krumholz HM. Sources of ethical conflict in medical

well-being and the quality of patient care. housestaff training: a qualitative study. Am J Med

2004;116:402–7

10 Green MJ, Farber NJ, Ubel PA, et al. Lying to each other –

Conclusion when internal medicine residents use deception with

tumor colleagues. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:2317–23

The typology shows the wealth of ethical chal- 11 Sinclair S. Making doctors: an institutional apprenticeship.

lenges faced by house officers. To deal adequately Oxford: Berg, 1997

12 Green MJ, Mitchell G, Stocking C, Cassel CK, Siegler M.

with these challenges, house officers and medical

Do actions reported by physicians in training conflict with

students should receive appropriate and problem- consensus guidelines on ethics? Arch Intern Med

specific training at the undergraduate level and 1996;156:298–304

during the first years of clinical practice. The issues 13 Paice E, Rutter H, Wetherall M, Winder B, McManus IC.

Stressful incidents, stress and coping strategies in the

in Table 1 tend to fall within what has been called pre-registration house officer year. Med Educ

the ‘ethics of the ordinary’ rather than the more 2002;36:56–65

dramatic ethical problems which, although fasci- 14 Clark PA. What residents are not learning: observations in

an NICU. Acad Med 2001;76:419–24

nating, may be far removed from the realities of life 15 Lambert TW, Goldacre MJ, Evans J. Views of junior

as a house officer.25 Although the proposed core doctors about their work: survey of qualifiers of 1993 and

curriculum in medical ethics and law in the UK 1996 from United Kingdom medical schools. Med Educ

2000;34:348–54

incorporates several of the issues identified in our 16 Bruce CT, Thomas PS, Yates DH. Health and stress in

typology, it also includes topics such as the ethics Australian interns. Intern Med J 2003;33:392–5

of the new genetics and aspects of resource alloca- 17 Bellini LM, Baime M, Shea AJ. Variation of mood and

tion which are of secondary importance to most empathy during internship. JAMA 2002;287:3143–6

18 Baldwin DC, Daugherty SR, Rowley BD. Unethical and

medical students.26 We suggest that undergradu- unprofessional conduct observed by residents during their

ate medical ethics curricula, necessarily con- first year of training. Acad Med 1998;73:1195–1200

strained by the demands of other subjects, should 19 Feudtner C, Christakis DA. Do clinical clerks suffer ethical

erosion? Students’ perceptions of their ethical

give priority to the real-life issues that students environment and personal development. Acad Med

will encounter in their first years of practice. A 1994;69:670–9

strong emphasis on the types of ethical problems 20 Testerman JK, Morton KR, Loo LK, Worthley JS,

Lamberton HH. The natural history of cynicism in

we have described, rather than the classic bioethi- physicians. Acad Med 1996;71:S43–S45

cal dilemmas, would best equip graduates for the 21 O’Rourke A. Dealing with prejudice. J Med Ethics

challenges of life as a junior doctor. Our typology 2001;27:123–5

can serve as a useful resource for teachers of medi- 22 Kushner TK, Thomasma DC, editors. Ward ethics:

Dilemmas for medical students and doctors in training..

cal ethics and law and for educators involved in Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001

curriculum development. 23 Christakis DA, Feudtner C. Temporary matters: the ethical

consequences of transient social relationships in medical

training. JAMA 1997;278:739–43

References 24 Goldacre M, Stear S, Lambert T. The pre-registration year:

The trainees’ experience. Med Educ 1997;31(Suppl 1)

1 Finucane P, O’Dowd T. Working and training as an intern:

:57–60

a national survey of Irish interns. Med Teacher

2005;27:107–13 25 Worthley JA. The ethics of the ordinary in healthcare:

2 Daugherty SR, Baldwin DC, Rowley BD. Learning, concepts and cases. Chicago: Health Administration Press,

satisfaction, and mistreatment during medical internship – 1997

a national survey of working conditions. JAMA 26 Doyal L, Gillon R. Medical ethics and law as a core subject

1998;279:1194–9 in medical education. BMJ 1998;316:1623–4

70 J R Soc Med 2008: 101: 67–70. DOI 10.1258/jrsm.2007.070412

You might also like

- ASD Diagnosis Tools - UpToDateDocument3 pagesASD Diagnosis Tools - UpToDateEvy Alvionita Yurna100% (1)

- BIOETHICS 1.01 Introduction To Bioethics - ValenzuelaDocument4 pagesBIOETHICS 1.01 Introduction To Bioethics - ValenzuelaMon Kristoper CastilloNo ratings yet

- Maxillofacial Notes DR - Mahmoud RamadanDocument83 pagesMaxillofacial Notes DR - Mahmoud Ramadanaziz200775% (4)

- BIOETHICS Class Notes 2019Document75 pagesBIOETHICS Class Notes 2019ManojNo ratings yet

- Business Plan Example - Little LearnerDocument26 pagesBusiness Plan Example - Little LearnerCourtney mcintosh100% (1)

- Ethico Moral Aspects of Nursing 2018Document50 pagesEthico Moral Aspects of Nursing 2018Zyla De SagunNo ratings yet

- Multi-Wing Engineering GuideDocument7 pagesMulti-Wing Engineering Guidea_salehiNo ratings yet

- Philo 173 - 2 - 11Document197 pagesPhilo 173 - 2 - 11Alexie Francis Tobias0% (1)

- Bioethics ReviewerDocument37 pagesBioethics Reviewerangel syching0% (1)

- Chemical Engineering Projects List For Final YearDocument2 pagesChemical Engineering Projects List For Final YearRajnikant Tiwari67% (6)

- Lichens - Naturally Scottish (Gilbert 2004) PDFDocument46 pagesLichens - Naturally Scottish (Gilbert 2004) PDF18Delta100% (1)

- The Vapour Compression Cycle (Sample Problems)Document3 pagesThe Vapour Compression Cycle (Sample Problems)allovid33% (3)

- Latest Low NOx Combustion TechnologyDocument7 pagesLatest Low NOx Combustion Technology95113309No ratings yet

- Pigeon Disease - The Eight Most Common Health Problems in PigeonsDocument2 pagesPigeon Disease - The Eight Most Common Health Problems in Pigeonscc_lawrence100% (1)

- Chapter 1 Ethical Principles and Concepts in MedicDocument10 pagesChapter 1 Ethical Principles and Concepts in MedicSahitt SahitiNo ratings yet

- MacKenzie - What Would A Good Doctor Do? Re Ections On The Ethics of MedicineDocument4 pagesMacKenzie - What Would A Good Doctor Do? Re Ections On The Ethics of MedicineCecitorNo ratings yet

- Re-Defining Moral Distress: A Systematic Review and Critical Re-Appraisal of The Argument-Based Bioethics LiteratureDocument16 pagesRe-Defining Moral Distress: A Systematic Review and Critical Re-Appraisal of The Argument-Based Bioethics Literatureadhafauzihendrawan2004No ratings yet

- Competency Areas: Area 1: Professional Responsibilities Area 2: CommunicationDocument16 pagesCompetency Areas: Area 1: Professional Responsibilities Area 2: CommunicationttsxxxNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Ethics: GSDMSFI: BioethicsDocument18 pagesIntroduction To Ethics: GSDMSFI: BioethicsJulanni SawabeNo ratings yet

- Microethics The Ethics of Everyday CliniDocument7 pagesMicroethics The Ethics of Everyday ClinimghaseghNo ratings yet

- Module 20 - Applied Ethics Ch-2 - 2Document9 pagesModule 20 - Applied Ethics Ch-2 - 2tamodeb2No ratings yet

- Lecture - Week 3 & Week 4Document58 pagesLecture - Week 3 & Week 4ون توNo ratings yet

- Analisis Jurnal Moral Dalam Praktik KebidananDocument25 pagesAnalisis Jurnal Moral Dalam Praktik Kebidanannovita utamiNo ratings yet

- 03 Dilemma & 04 Biomedical Ethics Discorse (Prof Hakimi)Document54 pages03 Dilemma & 04 Biomedical Ethics Discorse (Prof Hakimi)Zuzu FinusNo ratings yet

- Mare Moraldistress2016Document9 pagesMare Moraldistress2016Marie AsyethNo ratings yet

- Intoduction To Nursing EthicsDocument17 pagesIntoduction To Nursing EthicsAnjo Pasiolco CanicosaNo ratings yet

- Moral AssingmentDocument25 pagesMoral AssingmentLeen NisNo ratings yet

- Patricia Ann Potter - Anne Griffin Perry - Patricia A Stockert - Amy Hall - Fundamentals of Nursing-Elsevier Mosby (2013) - 321-330Document17 pagesPatricia Ann Potter - Anne Griffin Perry - Patricia A Stockert - Amy Hall - Fundamentals of Nursing-Elsevier Mosby (2013) - 321-330Rachma WatiNo ratings yet

- Moral Distress' - Time To Abandon A Flawed Nursing Construct Nurs Ethics-2015-JohnstoneDocument10 pagesMoral Distress' - Time To Abandon A Flawed Nursing Construct Nurs Ethics-2015-JohnstoneOscar PerezNo ratings yet

- Nursing Ethics 2nd Ed - Look Inside SampleDocument27 pagesNursing Ethics 2nd Ed - Look Inside SampleEnfermería UPB Salud PúblicaNo ratings yet

- Dental Ethics and Jurisprudence - A Review PDFDocument4 pagesDental Ethics and Jurisprudence - A Review PDFMichelle RobledoNo ratings yet

- Medical Ethics and A Ethical Dilema SDocument10 pagesMedical Ethics and A Ethical Dilema SRyukoNo ratings yet

- The Implications of Medical Ethics: A To ResortDocument9 pagesThe Implications of Medical Ethics: A To ResortOmarNo ratings yet

- NLM Sas 7Document13 pagesNLM Sas 7Zzimply Tri Sha UmaliNo ratings yet

- Inrtoduction of Nursing EthicesDocument14 pagesInrtoduction of Nursing EthicesBala UrmarNo ratings yet

- The Importance of Ethics in Health Care SystemDocument4 pagesThe Importance of Ethics in Health Care SystemHellen MunetsiNo ratings yet

- Notes For ArticleDocument5 pagesNotes For ArticleRamil Andrea BoybantingNo ratings yet

- Health Care Ethics 6th Edition 6th EditionDocument61 pagesHealth Care Ethics 6th Edition 6th Editionreynaldo.bailey262100% (50)

- Kaidah Dasar Bioetika & Prima FacieDocument60 pagesKaidah Dasar Bioetika & Prima FacieSamdiSutantoNo ratings yet

- 4-Prof. Sajid Darmadipura - Moral PhilosophyDocument38 pages4-Prof. Sajid Darmadipura - Moral Philosophyria andrianaNo ratings yet

- KD BN Prima Facie 2013Document60 pagesKD BN Prima Facie 2013Aldo HamkaNo ratings yet

- Partea Intunecata A EticiiDocument7 pagesPartea Intunecata A EticiiRamona Iocsa PoraNo ratings yet

- Moral Accounts and Membership Categorization in Primary Care Medical InterviewsDocument12 pagesMoral Accounts and Membership Categorization in Primary Care Medical InterviewstiengvietthuongyeuNo ratings yet

- Ethics: 3 Descriptions of What Ethics Is All AboutDocument47 pagesEthics: 3 Descriptions of What Ethics Is All AboutAli IgnacioNo ratings yet

- Bioethics: Chapter E10Document14 pagesBioethics: Chapter E10Jimmy R. JosephNo ratings yet

- Hce Chapter 1Document19 pagesHce Chapter 1Aby MauanayNo ratings yet

- Learning Packet 1 Introduction Key Concepts Updated For Nursing Students EditedDocument15 pagesLearning Packet 1 Introduction Key Concepts Updated For Nursing Students EditedJhon Mhark GarinNo ratings yet

- Nursing EthicsDocument6 pagesNursing EthicsAliza Bea CastroNo ratings yet

- Davidsin, KurtDocument22 pagesDavidsin, KurtArie BaldwellNo ratings yet

- N M D E W E: Urse Oral Istress and Thical ORK NvironmentDocument10 pagesN M D E W E: Urse Oral Istress and Thical ORK Nvironmenthala yehiaNo ratings yet

- The "Ethics" of Organizational/Institutional Ethics in A Pluralistic Setting: Conflicts of Interests, Values, and GoalsDocument16 pagesThe "Ethics" of Organizational/Institutional Ethics in A Pluralistic Setting: Conflicts of Interests, Values, and GoalsSana AliNo ratings yet

- Research Papers Ethics and MoralityDocument4 pagesResearch Papers Ethics and Moralityafnknohvbbcpbs100% (1)

- Introduction To Ethics ReviewerDocument4 pagesIntroduction To Ethics ReviewerCheene Ann OgsocNo ratings yet

- Full Download Advancing Your Career Concepts in Professional Nursing 5th Edition Kearney Test BankDocument36 pagesFull Download Advancing Your Career Concepts in Professional Nursing 5th Edition Kearney Test Bankjeissyskylan100% (41)

- HCE Module 1 - Introduction To Health Care EthicsDocument4 pagesHCE Module 1 - Introduction To Health Care EthicsAlaiza AvergonzadoNo ratings yet

- Booklet EthicsDocument35 pagesBooklet EthicsAhmed MarmashNo ratings yet

- Term Paper in Research Final LastDocument7 pagesTerm Paper in Research Final LastNarayan Kumar GhimireNo ratings yet

- Bioethics: S T Philosophical Issues of PracticeDocument15 pagesBioethics: S T Philosophical Issues of PracticeSNo ratings yet

- Bioethics: Walbert F. Delos Santos, RN - MNDocument43 pagesBioethics: Walbert F. Delos Santos, RN - MNmaidymae lopezNo ratings yet

- Ethics Challenges in Forensic Psychiatry and PsychDocument4 pagesEthics Challenges in Forensic Psychiatry and PsychGBNo ratings yet

- Bio-Ethics Word PPPDocument105 pagesBio-Ethics Word PPPManojNo ratings yet

- Powerpoint For Wildlife and Ecotourism Professional EthicsDocument157 pagesPowerpoint For Wildlife and Ecotourism Professional Ethicsaklilu mamoNo ratings yet

- Running Head: Applying Ethical Principles 1Document7 pagesRunning Head: Applying Ethical Principles 1Cate siz100% (1)

- Darby RESOLVINGETHICSDILEMMAS 2018Document19 pagesDarby RESOLVINGETHICSDILEMMAS 2018Shaima ShariffNo ratings yet

- Clinical Psychology - Midterm ReviewerDocument10 pagesClinical Psychology - Midterm ReviewerALEXIS LAROANo ratings yet

- Bioethics and Clinical Practice The Case of The Dental ServiceDocument3 pagesBioethics and Clinical Practice The Case of The Dental ServiceInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Advancing Your Career Concepts in Professional Nursing 5th Edition Kearney Test BankDocument25 pagesAdvancing Your Career Concepts in Professional Nursing 5th Edition Kearney Test BankNathanToddkprjq100% (53)

- Experiments in Love and Death: Medicine, Postmodernism, Microethics and the BodyFrom EverandExperiments in Love and Death: Medicine, Postmodernism, Microethics and the BodyNo ratings yet

- Total Compensation Strategy: by Stephen F. O'Byrne, Stern Stewart & CoDocument10 pagesTotal Compensation Strategy: by Stephen F. O'Byrne, Stern Stewart & Co042986iNo ratings yet

- Design by Deception PDFDocument10 pagesDesign by Deception PDFRosalba LoydeNo ratings yet

- BE PPT RayeesDocument10 pagesBE PPT Rayeesvarun_vashisht49No ratings yet

- AirtelDocument16 pagesAirtelArun ShettyNo ratings yet

- A Project Report On A Study On Amul Taste of India: Vikash Degree College Sambalpur University, OdishaDocument32 pagesA Project Report On A Study On Amul Taste of India: Vikash Degree College Sambalpur University, OdishaSonu PradhanNo ratings yet

- Guides To The Freshwater Invertebrates of Southern Africa Volume 2 - Crustacea IDocument136 pagesGuides To The Freshwater Invertebrates of Southern Africa Volume 2 - Crustacea IdaggaboomNo ratings yet

- Weld Metal Overlay & CladdingDocument2 pagesWeld Metal Overlay & CladdingbobyNo ratings yet

- Riber 6-s1 SP s17-097 336-344Document9 pagesRiber 6-s1 SP s17-097 336-344ᎷᏒ'ᏴᎬᎪᏚᎢ ᎷᏒ'ᏴᎬᎪᏚᎢNo ratings yet

- Enviroline 2405: Hybrid EpoxyDocument4 pagesEnviroline 2405: Hybrid EpoxyMuthuKumarNo ratings yet

- DEIR Appendix LDocument224 pagesDEIR Appendix LL. A. PatersonNo ratings yet

- Anti Stain Nsl30 Super - Msds - SdsDocument8 pagesAnti Stain Nsl30 Super - Msds - SdsS.A. MohsinNo ratings yet

- 2022-Brochure Neonatal PiccDocument4 pages2022-Brochure Neonatal PiccNAIYA BHAVSARNo ratings yet

- Itrogen: by Deborah A. KramerDocument18 pagesItrogen: by Deborah A. KramernycNo ratings yet

- Oil ShaleDocument13 pagesOil Shalergopi_83No ratings yet

- Heteropolyacids FurfuralacetoneDocument12 pagesHeteropolyacids FurfuralacetonecligcodiNo ratings yet

- Mainstreaming Gad Budget in The SDPDocument14 pagesMainstreaming Gad Budget in The SDPprecillaugartehalagoNo ratings yet

- India Wine ReportDocument19 pagesIndia Wine ReportRajat KatiyarNo ratings yet

- Castle 1-3K E ManualDocument26 pagesCastle 1-3K E ManualShami MudunkotuwaNo ratings yet

- 2019 06 28 PDFDocument47 pages2019 06 28 PDFTes BabasaNo ratings yet

- Pay Details: Earnings Deductions Code Description Quantity Amount Code Description AmountDocument1 pagePay Details: Earnings Deductions Code Description Quantity Amount Code Description AmountVee-kay Vicky KatekaniNo ratings yet

- Food Processing NC II - SAGDocument4 pagesFood Processing NC II - SAGNylmazdahr Sañeud DammahomNo ratings yet

- Topic of Assignment: Health Wellness and Yoga AssignmentDocument12 pagesTopic of Assignment: Health Wellness and Yoga AssignmentHarsh XNo ratings yet

- Soil Biotechnology (SBT) - Brochure of Life LinkDocument2 pagesSoil Biotechnology (SBT) - Brochure of Life Linkiyer_lakshmananNo ratings yet

- ZJZJP Roots Vauum PumpDocument8 pagesZJZJP Roots Vauum PumpAnonymous Tj3ApePIrNo ratings yet

- Offender TypologiesDocument8 pagesOffender TypologiesSahil AnsariNo ratings yet