Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Manegament VA in Obstetricia

Uploaded by

Leandro Gonzalez MorenoOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Manegament VA in Obstetricia

Uploaded by

Leandro Gonzalez MorenoCopyright:

Available Formats

Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology

Section Editor: Cynthia A. Wong

FOCUSED REVIEW

CME

The Unanticipated Difficult Intubation in Obstetrics

Jill M. Mhyre, MD, and David Healy, MD

In this focused review, we discuss an algorithm specifically for the unanticipated difficult

intubation in obstetrics. This generic algorithm emphasizes a standardized and prespecified

sequence of interventions to provide safe, efficient, and effective airway management for the

emergency obstetric surgical patient. Individual institutions and anesthesia providers are encour-

aged to use this framework to select specific pieces of equipment for each step, and to create regular

opportunities for all obstetric anesthesia providers to become facile with each airway device and to

integrate the algorithm under simulated conditions. (Anesth Analg 2011;112:648–52)

A pproximately 1 in 300 obstetric patients who un-

dergo the induction of general anesthesia will have

a failed intubation with standard direct laryngos-

copy.1–3 The most effective strategy to manage the difficult

The anesthetic induction drug should be selected based

on availability and overall clinical condition of the patient.

Succinylcholine provides better intubating conditions more

rapidly than rocuronium, with an average recovery time of

airway in obstetrics is to avoid it. However, once rapid ⬍10 minutes.17 Gentle mask ventilation before laryngos-

sequence induction of general anesthesia is selected, the copy may be considered in fasted patients.18 To maximize

anesthesiologist should have a preformulated strategy to oxygenation and minimize gastric insufflation, any attempt

manage the unanticipated difficult intubation.4 Although at ventilation should be an optimized attempt, character-

comprehensive difficult airway algorithms are available,5,6 ized by oral airway insertion, jaw thrust, cricoid pressure

a well-rehearsed algorithm specific for the obstetric patient adjustment, and a well-fitting facemask.

may be more useful in this setting.7–12 Figure 1 is a For the first intubation attempt, priorities include speed, a

suggested algorithm that synthesizes existing documents in high rate of success, and minimal airway trauma. Standard

a concise format. This focused review expands on the direct laryngoscopy to insert a styletted small-diameter endotra-

algorithm and discusses the rationale behind it. cheal tube remains the gold standard for tracheal intubation in

Before the anesthetic induction, practitioners should

obstetrics. Cricoid pressure is controversial and discussion of its

consider aspiration prophylaxis and optimize patient and

use is beyond the scope of this review. However, cricoid pressure

table position, oxygen administration, operator, medication

should be reduced, adjusted (BURP: backward, upward, right-

dosing, and equipment. For most women, particularly

ward pressure), or released if necessary to facilitate intuba-

those who are obese, the optimal position is ramped with

tion or ventilation.19 –21 Success rates for each intubation

left uterine displacement. The ideal ramp aligns the exter-

attempt may be further improved by gum elastic bougie

nal auditory meatus with the xiphoid process in a horizon-

tal plane.13 Optimal oxygenation is essential to achieve the insertion, a smaller-diameter endotracheal tube, and minor

longest possible duration of apnea before desaturation, and head position adjustments.

requires 3 to 5 minutes of tidal volume breathing with 100% If intubation fails, mask ventilation is recommended to

oxygen14 or 8 deep breaths over 60 seconds.14 –16 Equip- oxygenate the patient, assess the ease of ventilation, and

ment should be immediately available for the entire airway provide time to set up equipment for the second intubation

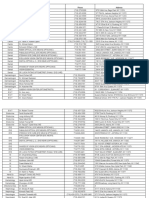

management algorithm. Table 1 presents a suggested list of strategy.15,16,18 A 2-handed technique may improve gas

basic equipment that should be prepared on the work exchange if mask ventilation is difficult. For patients who

surface of the anesthesia machine before inducing any remain well oxygenated, it may be appropriate to move

obstetric anesthetic. Remaining equipment should be immediately to the second intubation attempt.

stored in a portable storage unit located in the obstetric The backup intubation strategy should include familiar

operative suite.4 equipment, with options listed in Table 2. The specific

strategy is less important than expertise in deploying it.

From the Department of Anesthesiology, The University of Michigan Health Videolaryngoscopy is becoming the rescue strategy of

System, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

choice, and some authors even advocate it as the primary

Accepted for publication November 24, 2010.

laryngoscopic technique. However, at this time, compara-

Supported by the Department of Anesthesiology, The University of Michi-

gan Health System, Ann Arbor, MI. tive studies among obstetric patients are not available.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Three small series describe obstetric airway management

Address correspondence and reprint requests to Jill M. Mhyre, MD, Depart- with an Airtraq22,23 or a GlideScope.24 Comparative studies

ment of Anesthesiology, The University of Michigan Health System, L3622 among non-obstetric patients with predicted difficult intu-

Women’s Hospital, 1500 E. Medical Center Dr., SPC 5278, Ann Arbor, MI

48109-5278. Address e-mail to jmmhyre@umich.edu. bation do not favor any particular videolaryngoscope,25 but

Copyright © 2011 International Anesthesia Research Society speed, simplicity, reliability, and efficiency are desirable

DOI: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31820a91a6 characteristics.

648 www.anesthesia-analgesia.org March 2011 • Volume 112 • Number 3

Unanticipated Difficult Intubation in Obstetrics

Figure 1. Suggested algorithm. *Adjust cricoid pressure; backward, upward, rightward pressure (BURP); bougie; minor position adjustments.

†Oral airway, jaw thrust, adjust cricoid pressure, 2-handed technique.

techniques and equipment for each step of the general

Table 1. Suggested Airway Equipment to Maintain algorithm.26 Each institution should establish a program by

for the Induction of Obstetric Anesthesia

which all personnel responsible for obstetric patients be-

Facemask and oral airways

come facile with each airway device, and are able to

Gauze and a tongue blade

2 working laryngoscope handles integrate the series of techniques into the difficult airway

Macintosh blades: sizes 3 and 4 algorithm.26,27 The true cost of each device will include not

6.5 styletted endotracheal tube with an empty 10-mL syringe connected only the cost of use for each emergency, but also the cost of

to the pilot balloon

training all providers to a level of proficiency, and main-

Backup endotracheal tubes in a range of sizes

Gum elastic bougie taining the equipment in an ongoing state of readiness. An

Primary extraglottic airway appropriate for a 70- to 100-kg person (Table 3) effective device may be considered cost saving if it avoids

Suction adequate to remove secretions the medical, legal, and emotional consequences of just one

failed airway.

Help should be requested as soon as difficulty is antici-

Although each potential device might be optimal under pated or encountered. The response will depend on insti-

select circumstances, the obstetric patient with failed intu- tutional resources. At a minimum, the institutional difficult

bation will be served best by clarity of purpose and action. airway algorithm should specify the appropriate respond-

Therefore, the institutional algorithm should select specific ers and an efficient means to contact them.

March 2011 • Volume 112 • Number 3 www.anesthesia-analgesia.org 649

FOCUSED REVIEW

Table 2. Options for Secondary Table 3. Selected Options for

Intubation Equipment Extraglottic Airways

Manufacturer Manufacturer

Direct laryngoscopes Supraglottic airways with an

McCoy blade esophageal drain

Miller blade inserted by a LMA ProSeal™ LMA North America, San Diego, CA

paramolar approach LMA Supreme™ LMA North America, San Diego, CA

Intubation guides i-gel姞 Intersurgical Ltd., Wokingham, UK

LMA FasTrach™ ⫾ LMA North America, San Diego, CA Supraglottic airways designed

fiberoptic bronchoscope to facilitate intubation

Air-Q™ ⫾ fiberoptic Cookgas, St. Louis, MO Air-QTM Cookgas, St. Louis, MO

bronchoscope LMA FasTrach™ LMA North America, San Diego, CA

Lighted stylet Supraglottic airway without an

Videolaryngoscopes esophageal drain

C-Mac姞 Karl Storz, Tuttlingen, Germany Classic LMA™, LMA Unique™ LMA North America, San Diego, CA

GlideScope姞 Verathon Medical, Bothell, WA SLIPA™ (50-mL esophageal SLIPA Medical Ltd., Douglas, Isle

Airtraq姞 Prodol Ltd., Vizcaya, Spain reservoir) of Man, UK

Pentax-AWS™ Hoya Corp., Tokyo, Japan Retroglottic airways with an

Truview EVO2™ Truphatek Holdings Ltd., Netanya, esophageal balloon and an

Israel esophageal drain

McGRATH姞 Series5 Aircraft Medical, Edinburgh, UK Laryngeal Tube VBM Medizintechnik, Sulz,

McGRATH姞 MAC Aircraft Medical, Edinburgh, UK (LTS姞, LTS-D™) Germany

Coopdech姞 C-Scope Daiken Medical Co., Osaka, Japan EasyTube姞 Rüsch, a Teleflex Medical

Optical stylets Company, Durham, NC

Bonfils™ Karl Storz, Tuttlingen, Germany Combitube姞 Covidien-Nellcor, Boulder, CO

Levitan™ Clarus Medical, Minneapolis, MN

Shikani SOS™ Clarus Medical, Minneapolis, MN

Video System™ (CVS) Clarus Medical, Minneapolis, MN

Video RIFL姞 AI Medical Devices, Inc.,

Williamston, MI cesarean delivery patients managed under general anesthe-

sia.43 LMA insertion was successful on the first attempt in

98% of patients and effective within 3 attempts for all but 7

patients, with no cases of regurgitation or aspiration in the

Oxygenation and ventilation take priority over intubation entire series. Cricoid pressure release is recommended to

when the hemoglobin saturation decreases below 90%, cya- facilitate extraglottic airway insertion, and may be reap-

nosis develops, or after 2 intubation attempts fail. Each plied once adequate ventilation is established.43– 45

attempt entails one insertion of the relevant airway equip- To avoid aspiration with an extraglottic airway, it is

ment by a single provider, and should be completed in ⬍1 necessary to ensure proper siting of the device, select a

minute. A review of the American Society of Anesthesiologists device with an esophageal drain or an esophageal balloon

obstetric closed claims data suggests that repeated attempts at or both, maintain cricoid pressure as ventilation permits

intubation may result in progressive difficulty in ventilation that (releasing and reapplying briefly during insertion), ask the

ultimately leads to complete airway obstruction.28 surgeons to limit fundal pressure during delivery, and

If intubation fails, then positive pressure ventilation maintain adequate anesthesia. Intraoperative coughing can

with either a facemask or an extraglottic airway may be precipitate regurgitation and dislodge the device.46 In the

used to await, and then support, spontaneous ventilation. event of regurgitation with an extraglottic airway, experts

Once adequate ventilation is established, the decision to recommend positioning the patient head down and on her

proceed with surgery or awaken the patient weighs the side if possible, leaving the airway in place, suctioning the

risks of maternal aspiration and subsequent failed ventila- esophageal drain, inserting an orogastric tube to empty the

tion against the maternal and fetal consequences of delayed stomach contents, and consideration of fiberoptic intuba-

delivery. tion and bronchoscopy.46

Extraglottic airway options are listed in Table 3. The For emergent cesarean delivery with an unsecured air-

most important characteristic of an extraglottic airway used way, it is probably best to wait until the neonate has been

for airway rescue is rapid, reliable insertion. An esophageal delivered to consider additional attempts at definitive

drain, high sealing pressure, and features that facilitate airway management. Even after delivery, if ventilation is

intubation are desirable. Several case reports document adequate and the surgery is straightforward, attempts at

successful airway protection in the setting of copious intubation or surgical airway access may carry more risks

gastric contents removed through an esophageal drain.29 –32 than benefits. If intubation is essential, then an optical

Retropharyngeal tube airways, such as the Laryngeal Tube, guidance technique may help to limit further airway

have a relatively narrow profile, and may be preferred in trauma with repeated blind attempts.

the setting of significant oropharyngeal edema.12,33 If ventilation becomes impossible at any point, then

A number of case reports and small series have described the patient’s neck and head should be repositioned, and

successful obstetric airway rescue with a Classic laryngeal equipment prepared for a surgical airway. In the case of

mask airway (LMA),2,34 –36 ProSeal LMA,2,35,37– 40 LMA Fas- impossible mask ventilation, a single attempt to insert an

Trach,2,41 Combitube,42 and Laryngeal Tube-S.31 The Classic extraglottic airway could be completed while an assistant

LMA has been used electively in a series of 1067 scheduled prepares equipment for needle or cannula cricothyrotomy.

650 www.anesthesia-analgesia.org ANESTHESIA & ANALGESIA

Unanticipated Difficult Intubation in Obstetrics

Further noninvasive airway management should be com- 4. American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Obstetric

pleted by a second provider while the surgical airway is Anesthesia. Practice guidelines for obstetric anesthesia: an

updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists

secured without delay.10,47 Task Force on Obstetric Anesthesia. Anesthesiology 2007;

Multiple invasive airway techniques have been com- 106:843– 63

pared with varying results and are beyond the scope of this 5. American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Manage-

review. All invasive airway techniques may introduce ment of the Difficult Airway. Practice guidelines for management

morbidity; frequent training is thought to facilitate effi- of the difficult airway: an updated report by the American Society

of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Management of the Difficult

ciency, effectiveness, and safety. Proficiency with the Airway. Anesthesiology 2003;98:1269 –77

Melker percutaneous cricothyrotomy dilational set (Cook 6. Henderson JJ, Popat MT, Latto IP, Pearce AC. Difficult Airway

Medical Inc., Bloomington, IN) may require as few as 5 Society guidelines for management of the unanticipated diffi-

insertion simulations48; however, performance seems to cult intubation. Anaesthesia 2004;59:675–94

decline within 3 months, and frequent retraining is neces- 7. Dennehy KC, Pian-Smith MC. Airway management of the

parturient. Int Anesthesiol Clin 2000;38:147–59

sary.a Regardless, review of closed claims data for injuries 8. Ezri T, Szmuk P, Evron S, Geva D, Hagay Z, Katz J. Difficult

attributed to invasive airway access suggests that the most airway in obstetric anesthesia: a review. Obstet Gynecol Surv

serious complication of any emergent invasive airway 2001;56:631– 41

technique is a failure to apply the technique early enough, 9. Nair A, Alderson JD. Failed intubation drill in obstetrics. Int J

before the consequences of significant hypoxia develop.49 Obstet Anesth 2006;15:172– 4

10. Walls RM. The emergency airway algorithms. In: Walls RM,

Failed oxygenation resulting in maternal cardiac arrest Murphy MF, eds. Manual of Emergency Airway Management.

in a patient ⬎20 weeks’ gestational age mandates perimor- Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams &

tem cesarean delivery within 5 minutes of the arrest to Wilkins, 2008:9 –22

optimize the effectiveness of chest compressions for mater- 11. Vasdev GM, Harrison BA, Keegan MT, Burkle CM. Manage-

nal resuscitation.50,51 ment of the difficult and failed airway in obstetric anesthesia.

J Anesth 2008;22:38 – 48

General anesthesia continues to have an essential role in 12. Vaida SJ, Pott LM, Budde AO, Gaitini LA. Suggested algorithm

obstetrics whenever neuraxial anesthesia is contraindicated or for management of the unexpected difficult airway in obstetric

fails, or surgical urgency demands it. Usually, airway man- anesthesia. J Clin Anesth 2009;21:385– 6

agement is uneventful, but unanticipated difficult intubations 13. Brodsky JB, Lemmens HJ, Brock-Utne JG, Saidman LJ, Levitan

do continue to occur. To prepare, anesthesiologists should R. Anesthetic considerations for bariatric surgery: proper po-

sitioning is important for laryngoscopy. Anesth Analg

select and verify appropriate airway equipment, establish 2003;96:1841–2

reliable systems for equipment maintenance, and ensure 14. Tanoubi I, Drolet P, Donati F. Optimizing preoxygenation in

comprehensive training in the use of these devices according adults. Can J Anaesth 2009;56:449 – 66

to a succinct airway algorithm. 15. Baraka AS, Taha SK, Aouad MT, El-Khatib MF, Kawkabani NI.

Preoxygenation: comparison of maximal breathing and tidal

volume breathing techniques. Anesthesiology 1999;91:612– 6

16. Chiron B, Laffon M, Ferrandiere M, Pittet JF, Marret H, Mercier

DISCLOSURES C. Standard preoxygenation technique versus two rapid tech-

Name: Jill M. Mhyre, MD. niques in pregnant patients. Int J Obstet Anesth 2004;13:11– 4

Role: This author helped review the literature and write the 17. Perry JJ, Lee JS, Sillberg VA, Wells GA. Rocuronium versus

manuscript. succinylcholine for rapid sequence induction intubation. Co-

chrane Database Syst Rev 2008;2:CD002788

Attestation: Jill M. Mhyre approved the final manuscript. 18. Crosby E. The difficult airway in obstetric anesthesia. In: Carin

Name: David Healy, MD. A, Hagberg M, eds. Benumof’s Airway Management: Prin-

Role: This author helped review the literature and write the ciples and Practice. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier,

manuscript. 2007:834 –58

Attestation: David Healy approved the final manuscript. 19. Ovassapian A, Salem MR. Sellick’s maneuver: to do or not do.

Anesth Analg 2009;109:1360 –2

20. Lerman J. On cricoid pressure: “may the force be with you.”

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Anesth Analg 2009;109:1363– 6

The authors acknowledge with appreciation Mary Lou Green- 21. de Souza DG, Doar LH, Mehta SH, Tiouririne M. Aspiration

field, MPH, MS, Lauren Cook, and Syed Shabbir for their work prophylaxis and rapid sequence induction for elective cesarean

delivery: time to reassess old dogma? Anesth Analg 2010;110:

on this project.

1503–5

22. Dhonneur G, Ndoko S, Amathieu R, Housseini LE, Poncelet C,

REFERENCES Tual L. Tracheal intubation using the Airtraq in morbid obese

1. Jenkins JG. Failed intubation in obstetric anesthesia: a reply. patients undergoing emergency cesarean delivery. Anesthesi-

Anaesthesia 2006;61:193– 4 ology 2007;106:629 –30

2. McDonnell NJ, Paech MJ, Clavisi OM, Scott KL. Difficult and 23. Riad W, Ansari T. Effect of cricoid pressure on the laryngo-

failed intubation in obstetric anaesthesia: an observational scopic view by Airtraq in elective caesarean section: a pilot

study of airway management and complications associated study. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2009;26:981–2

with general anaesthesia for caesarean section. Int J Obstet 24. Turkstra TP, Armstrong PM, Jones PM, Quach T. GlideScope

Anesth 2008;17:292–7 use in the obstetric patient. Int J Obstet Anesth 2010;19:123– 4

3. Djabatey EA, Barclay PM. Difficult and failed intubation in 25. Mihai R, Blair E, Kay H, Cook TM. A quantitative review and

3430 obstetric general anaesthetics. Anaesthesia 2009;64: meta-analysis of performance of non-standard laryngoscopes

1168 –71 and rigid fibreoptic intubation aids. Anaesthesia 2008;63:

745– 60

a

Prabhu A, Correa R, Wong D, Chung F. Cricothyroidotomy: learning and 26. Greenland KB, Edwards MJ, Beckmann L, Hutton N. Difficult

maintaining the skill for optimal performance. Difficult Airway Society airway management: a glass half empty. Anaesthesia

Annual Scientific Meeting, Oxford, UK, 2001. 2009;64:1024 –5

March 2011 • Volume 112 • Number 3 www.anesthesia-analgesia.org 651

FOCUSED REVIEW

27. Berkow LC, Greenberg RS, Kan KH, Colantuoni E, Mark LJ, 40. Sharma B, Sahai C, Sood J, Kumra VP. The ProSeal laryngeal

Flint PW, Corridore M, Bhatti N, Heitmiller ES. Need for mask airway in two failed obstetric tracheal intubation sce-

emergency surgical airway reduced by a comprehensive diffi- narios. Int J Obstet Anesth 2006;15:338 –9

cult airway program. Anesth Analg 2009;109:1860 –9 41. Minville V, N⬘Guyen L, Coustet B, Fourcade O, Samii K.

28. Davies JM, Posner KL, Lee LA, Cheney FW, Domino KB. Difficult airway in obstetric using Ilma-Fastrach. Anesth Analg

Liability associated with obstetric anesthesia: a closed claims 2004;99:1873

analysis. Anesthesiology 2009;110:131–9 42. Wissler RN. The esophageal-tracheal Combitube. Anesthesiol

29. Evans NR, Llewellyn RL, Gardner SV, James MF. Aspiration Rev 1993;20:147–52

prevented by the ProSeal laryngeal mask airway: a case report. 43. Han TH, Brimacombe J, Lee EJ, Yang HS. The laryngeal mask

Can J Anaesth 2002;49:413– 6 airway is effective (and probably safe) in selected healthy

30. Mark DA. Protection from aspiration with the LMA-ProSeal parturients for elective cesarean section: a prospective study of

after vomiting: a case report. Can J Anaesth 2003;50:78 – 80 1067 cases. Can J Anaesth 2001;48:1117–21

31. Zand F, Amini A. Use of the laryngeal tube-S for airway 44. Ansermino JM, Blogg CE. Cricoid pressure may prevent inser-

management and prevention of aspiration after a failed tra- tion of the laryngeal mask airway. Br J Anaesth 1992;69:465–7

cheal intubation in a parturient. Anesthesiology 2005;102:481–3 45. Brimacombe J, White A, Berry A. Effect of cricoid pressure on

32. Liew G, John B, Ahmed S. Aspiration recognition with an i-gel ease of insertion of the laryngeal mask airway. Br J Anaesth

airway. Anaesthesia 2008;63:786 1993;71:800 –2

33. Asai T, Matsumoto S, Shingu K, Noguchi T, Koga K. Use of the 46. Keller C, Brimacombe J, Bittersohl J, Lirk P, von Goedecke A.

laryngeal tube after failed insertion of a laryngeal mask airway. Aspiration and the laryngeal mask airway: three cases and a

Anaesthesia 2005;60:825– 6 review of the literature. Br J Anaesth 2004;93:579 – 82

34. Anderson KJ, Quinlan MJ, Popat M, Russell R. Failed intuba- 47. Murphy MF, Crosby ET. The algorithms. In: Hung OR, Mur-

tion in a parturient with spina bifida. Int J Obstet Anesth phy MF, eds. Management of the Difficult and Failed Airway.

2000;9:64 – 8 Columbus: McGraw-Hill Companies, 2008:15–28

35. Keller C, Brimacombe J, Lirk P, Puhringer F. Failed obstetric 48. Wong DT, Prabhu AJ, Coloma M, Imasogie N, Chung FF. What

tracheal intubation and postoperative respiratory support with is the minimum training required for successful cricothyroid-

the ProSeal laryngeal mask airway. Anesth Analg otomy? A study in mannequins. Anesthesiology 2003;98:

2004;98:1467–70 349 –53

36. Bailey SG, Kitching AJ. The laryngeal mask airway in failed 49. Peterson GN, Domino KB, Caplan RA, Posner KL, Lee LA,

obstetric tracheal intubation. Int J Obstet Anesth 2005;14:270 –1 Cheney FW. Management of the difficult airway: a closed

37. Awan R, Nolan JP, Cook TM. Use of a ProSeal laryngeal mask claims analysis. Anesthesiology 2005;103:33–9

airway for airway maintenance during emergency caesarean 50. Katz VL, Dotters DJ, Droegemueller W. Perimortem cesarean

section after failed tracheal intubation. Br J Anaesth delivery. Obstet Gynecol 1986;68:571– 6

2004;92:144 – 6 51. Vanden Hoek TL, Morrison LJ, Shuster M, Donnino M, Sinz E,

38. Vaida SJ, Gaitini LA. Another case of use of the ProSeal Lavonas EJ, Jeejeebhoy FM, Gabrielli A. Part 12: Cardiac Arrest

laryngeal mask airway in a difficult obstetric airway. Br J in Special Situations: 2010 American Heart Association Guide-

Anaesth 2004;92:905 lines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Car-

39. Cook TM, Brooks TS, Van der Westhuizen J, Clarke M. The diovascular Care. Circulation 2010;122:S829 – 61

Proseal LMA is a useful rescue device during failed rapid

sequence intubation: two additional cases. Can J Anaesth

2005;52:630 –3

652 www.anesthesia-analgesia.org ANESTHESIA & ANALGESIA

You might also like

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Pre-Writing Process 4 6 TTHDocument5 pagesPre-Writing Process 4 6 TTHyuypNo ratings yet

- Oral Medicine Total BooksDocument10 pagesOral Medicine Total Booksvignesh11vNo ratings yet

- History of Abnormal BehaviourDocument31 pagesHistory of Abnormal BehaviourAbdul NazarNo ratings yet

- 202331orig1s000: Clinical Pharmacology and Biopharmaceutics Review (S)Document37 pages202331orig1s000: Clinical Pharmacology and Biopharmaceutics Review (S)sadafNo ratings yet

- Updated Unang Yakap Checklist 1Document3 pagesUpdated Unang Yakap Checklist 1Myrel Cedron TucioNo ratings yet

- Medical Expense ReceiptDocument1 pageMedical Expense Receiptakhil kottediNo ratings yet

- (2021, May 6) - Florence Nightingale. Biography. NightingaleDocument6 pages(2021, May 6) - Florence Nightingale. Biography. Nightingale김서연No ratings yet

- HerbalismDocument18 pagesHerbalismmieNo ratings yet

- Health and Wellness: Distinguishing Screening, Evaluation and ExaminationDocument14 pagesHealth and Wellness: Distinguishing Screening, Evaluation and ExaminationsaddaqatNo ratings yet

- Copy of ონკოლოგია-ღვამიჩავა, შავდიაDocument636 pagesCopy of ონკოლოგია-ღვამიჩავა, შავდიაCoralinaNo ratings yet

- State Common Entrance Test CellDocument275 pagesState Common Entrance Test CellIndar SuryaNo ratings yet

- Orientation On DTP ME With DMOs - November 4 2022Document28 pagesOrientation On DTP ME With DMOs - November 4 2022Arlo Winston De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- List Some Important BooksDocument1 pageList Some Important Booksdnarayanarao48No ratings yet

- Pleno EVIDENCE BASED DENTISTRYDocument15 pagesPleno EVIDENCE BASED DENTISTRYNASTYHAIR 24No ratings yet

- Er Test DrillsDocument26 pagesEr Test DrillsconinitasNo ratings yet

- Faculty of Nursing Zagazig University Nursing Administration 4 Year ExamDocument16 pagesFaculty of Nursing Zagazig University Nursing Administration 4 Year ExamserviceNo ratings yet

- @ebookmedicin 2018 Davidson's Self Assessment in Medicine 1st EditionDocument444 pages@ebookmedicin 2018 Davidson's Self Assessment in Medicine 1st EditionBrian ARI100% (1)

- 81ae056a-2653-4148-b147-b5bdb3f5f389Document57 pages81ae056a-2653-4148-b147-b5bdb3f5f389Larissa Germana Silva Oliveira de AlencarNo ratings yet

- Community BrochureDocument1 pageCommunity BrochureDeadX GamingNo ratings yet

- History Taking ChecklistDocument3 pagesHistory Taking ChecklistDianeNo ratings yet

- Rachelle Manuel PobleteDocument4 pagesRachelle Manuel PobleteRachelle MondidoNo ratings yet

- Keeping Vivian IndependentDocument11 pagesKeeping Vivian Independentapi-439529581No ratings yet

- NURS FPX 6210 Assessment 2 Strategic PlanningDocument6 pagesNURS FPX 6210 Assessment 2 Strategic Planningjoohnsmith070No ratings yet

- TDM Exam Study Resources PDFDocument5 pagesTDM Exam Study Resources PDFDrosler MedqsNo ratings yet

- Nursing Simulation - Patient EvaluationDocument3 pagesNursing Simulation - Patient EvaluationAaronNo ratings yet

- Motivational InterviewingDocument10 pagesMotivational Interviewingcionescu_7No ratings yet

- Begs 183Document4 pagesBegs 183viploveNo ratings yet

- NS5e RW4 Ach Test U03Document4 pagesNS5e RW4 Ach Test U03kimkeep241No ratings yet

- 11 J.L. & Health 195Document19 pages11 J.L. & Health 195djranneyNo ratings yet

- Field of SpecialistDocument4 pagesField of Specialistapi-598083311No ratings yet