Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Counterrevolution in The Gulf Toby Jones

Uploaded by

adso12Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Counterrevolution in The Gulf Toby Jones

Uploaded by

adso12Copyright:

Available Formats

UNITED STates institute of peace

peaceBrieF89

United States Institute of Peace • www.usip.org • Tel. 202.457.1700 • Fax. 202.429.6063 April 15, 2011

Toby C. Jones Counterrevolution in the Gulf

E-mail: tobycjones@yahoo.com

Phone: 570.994.2870 Summary

• Saudi Arabia is pursuing a combination of domestic and regional policies that risk destabiliz-

ing the Persian Gulf and that risk undermining the United States interests there.

• Amid calls for political change, Saudi Arabia is failing to address pressing concerns about its

political system and the need for political reform. Instead of responding favorably to calls for

more political openness, the Kingdom is pursuing a risky domestic agenda, which ignores the

social, economic, and political grievances that might fuel popular mobilization.

• Saudi Arabia’s military intervention into Bahrain has escalated sectarian tensions in the Gulf.

The crackdown in Bahrain is not only provoking Iran and creating the conditions for a regional

crisis, but it is also creating new opportunities for Iran to expand its sphere of influence.

• The United States has reasons to maintain a strong relationship with Saudi Arabia. It also has

the leverage to encourage the Kingdom to refrain from escalating tensions in the Gulf and

further inflaming sectarian anxieties.

Unnerved by changes taking place across the Middle East and North Africa, Saudi Arabia has

sought to undertake drastic measures to ensure its security at home and in the region. However, its

measures are in fact achieving the opposite. Rather than dealing with the political aspirations of its

“

own citizens or those in neighboring Bahrain, where Riyadh has intervened militarily to help crush

[I]t is Saudi Arabia and its pro-democracy protests, Saudi Arabia is turning back the clock at home and provoking a potential

Arab allies that are inflaming crisis with Iran.

sectarian enmity. By project- Recent tactics used by this key American ally may be exacerbating security risks and creating an

ing their anxieties regionally, environment that will make it more difficult for the United States to secure its interests. Whether

Washington is prepared to accept Saudi Arabia’s strategy in the Gulf is a critical question. On one

Saudi Arabia has raised the

hand, the United States needs the kingdom, not least for their oil. On the other, the price of that

stakes and provoked a alliance has increased significantly in recent weeks.

potential regional showdown Saudi Arabia’s current strategy and the potential risks it entails is partly the result of its fears over

with Iran. Fears of deepening Iran’s growing hegemony in the region. But it is also partly the result of a shifting domestic balance

of power, a renewed sectarian approach to politics and a continued reluctance to pursue political

sectarian tensions in the Gulf

reform.

are now being realized. ”

Evading Reform

In recent years, Saudi citizens have pressed to reform a system that they believe is subject to royal

family abuse, rife with corruption, and one that encourages discrimination against religious mi-

norities and women. When King Abdullah ascended to the throne in 2005 many believed he was

© USIP 2011 • All rights reserved.

Counterrevolution in the Gulf

page 2 • PB 89 • April 15, 2011

a committed reformer, but he has demonstrated to be mostly committed to protecting the power

of the royal family. But even though he has not proven interested in creating space for greater

participation, Abdullah has ushered in significant changes. Most importantly, he has devoted

considerable energy to marginalizing religious hardliners and checking the power of some of the

Kingdom’s most odious religious figures.

While it is widely believed that the Al Saud has always ruled with the close cooperation of the

religious establishment, the relationship between the ruling family and the Kingdom’s senior

religious scholars has often been strained. Because prominent religious figures regularly clashed

with the Kingdom’s rulers on matters of domestic and foreign policy, Saudi elites struggled to

minimize the role of the clergy over the course of the 20th century. As oil revenues skyrocketed in

the 1970s, Riyadh found itself less dependent on the scholars for their support.

But at the end of the decade, domestic conflicts, including the seizure of the Grand Mosque in

Mecca by religious rebels in 1979, changed the balance of power in the Kingdom. In exchange

for a religious ruling allowing authorities to send security into the Grand Mosque to root out the

rebels, Riyadh was compelled to promise renewed influence for the religious establishment. In

the 1980s, the Kingdom pumped hundreds of millions of dollars into Islamic foundations, schools

and causes, including the anti-Soviet jihad in Afghanistan and Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein’s war

against Shiite Iran. Over the last three decades, religious scholars have exercised considerable

cultural and political power, often to the frustration and embarrassment of the Kingdom’s rulers.

King Abdullah has taken significant steps to restore the pre-1979 balance of power by sacking

controversial religious figures, seeking to centralize control over the judiciary, and challenging the

clergy on matters of women’s rights. The effect had been to rein in some of the Kingdom’s most

important religious institutions, including the notorious religious police.

Many Saudi citizens have respect for the king, but they remain frustrated with the glacial pace

of reform. Recent events in the Middle East -- most importantly the popular uprisings that toppled

governments in Tunisia and Egypt -- inspired some Saudi citizens to renew calls for change. So far,

efforts to seize upon regional momentum have resulted not in reform, but in the strengthening of

hardliners within the royal family.

Shutting Down the Day of Rage

Pro-reform activists launched calls to hold a Day of Rage on March 11, in which they hoped citizens

would turn out for demonstrations in cities across the country. Alarmed by Hosni Mubarak’s fall

from power in Egypt, Saudi authorities responded anxiously and harshly to stave off a similar

outcome at home. They sought various ways to outmaneuver their critics and crush any potential

popular uprising before it got started. To do so Riyadh dusted off a familiar playbook. In late

February, King Abdullah promised a multibillion dollar financial aid program in an effort to

co-opt dissenters. The regime also threatened would-be protesters. In early March, Saud al-Faisal,

the Saudi foreign minister, warned that authorities would “cut off any finger” raised against the

government in protest. Authorities also threatened fines and imprisonment for demonstrators.

Riyadh also enlisted the religious establishment for support. On March 7, the Senior Council of

Ulama, Saudi Arabia’s highest ranking religious authority, issued a statement declaring protests to

be un-Islamic. Considering Abdullah’s past efforts to curtail the power of the clergy, their renewed

support for the monarchy was a significant development.

On March 11, a heavy police presence made it virtually impossible for Saudi citizens to organize

publicly. Less than a week later the Saudi government announced a second sweeping package of

financial inducements, including housing subsidies, a jobs creation program, and unemployment

© USIP 2011 • All rights reserved.

Counterrevolution in the Gulf

page 3 • PB 89 • April 15, 2011

assistance. Flush with cash from high oil prices, Riyadh can afford to throw money at its deeply

rooted problems. It is a familiar strategy. While buying favor will likely quell dissent in the short

term, its longer-term effectiveness is uncertain.

A New Balance of Power

One of the most important outcomes of the result struggle to fend off public pressure appears to

be the reconfiguration of the Kingdom’s balance of power and the emergence of hardliners within

the royal family, most notably the controversial Minister of the Interior Prince Nayef, third in line to

the throne. As minister of the Interior and commander of Saudi Arabia’s domestic security forces,

Nayef was responsible for dispatching thousands of police to prevent demonstrations.

The decision to enlist the support of religious scholars indicates a reversal of Abdullah’s efforts to

marginalize the clerical establishment’s influence. Recent moves to support the clergy—and side-

line moderates—reinforce this conclusion. On March 18, alongside the announcement of material

support for Saudi citizens, the government also announced significant new levels of spending

on religious schools and institutions and expanded powers for the country’s religious police. On

April 2, the government sacked Ahmad al-Ghamdi, the head of the Mecca’s branch of the religious

police who last year claimed that Islam does not mandate gender segregation.

The potential renewal of clerical power in Saudi Arabia, particularly its most conservative

elements, is cause for concern. It is worth recalling that the ascendance in the 1980s of a genera-

tion of politically motivated clergy helped radicalize some Saudi citizens and contributed to the

globalization of violent extremism in subsequent decades.

Stoking Sectarian Tensions

There has also been a sectarian element to Saudi Arabia’s handling of its domestic crisis. In the

week leading up to the March 11 Day of Rage, small protests took place in Shiite neighborhoods

across the Eastern Province. Shiite demonstrators called for minor concessions, such as the end

of discrimination and the release of political prisoners. Saudi rulers seized on these small dem-

onstrations to cast the entire opposition as beholden to Iran and pursuing a sectarian agenda.

Prince al-Faisal remarked that the regime would “not tolerate any interference in our internal

affairs by any foreign party . . . and if we find any foreign interference, we will deal with this deci-

sively.” It is hard to tell if the regime’s attempt to portray their critics as agents of Iran succeeded

in dissuading protesters from taking to the streets. Anti-Shiism is deeply rooted in Saudi Arabian

society and may have convinced some not to throw their lot in with the Kingdom’s most despised

religious minority.

More importantly, the pretense of foreign meddling and the sectarian gambit allowed the

Kingdom’s rulers to justify their heavy-handed approach more generally as an effort to protect

national security rather than as an attempt to ignore the substance of the reformers’ agenda.

Regional Implications

The domestic anxieties on display in Riyadh have shaped the regime’s decision making in

neighboring Bahrain, another close American ally in the Gulf, as well. On March 14, in response to

mounting pressure on the Bahraini regime by tens of thousands of opposition protesters, Saudi

Arabia sent a contingent of around 1,000 military personnel (along with a small force from the

United Arab Emirates) into Manama to support efforts to crush the popular uprising there. The

resulting crackdown has been violent and brutal.

© USIP 2011 • All rights reserved.

Counterrevolution in the Gulf

page 4 • PB 89 • April 15, 2011

The Saudis have many reasons for not wanting to see the ruling al-Khalifa toppled from power

in Bahrain. The most important has to do with the possibility of a Shiite government taking over

in Manama. While Bahrain’s opposition is largely committed to democratic reform, it is true that

the vast majority of those protesting against the government come from the country’s majority

Shiite community. For the most part, however, Bahrain’s opposition has carefully avoided framing

their demands in sectarian terms. Whatever the actual substance of their opposition’s platform, the

governments in Riyadh and Manama have used religious affiliation and regional sectarian anxiet-

ies as an excuse to crackdown violently.

Leaders in both Bahrain and Saudi Arabia have warned against Iranian meddling and have

cynically suggested that the uprising in Bahrain was orchestrated by Tehran. After Saudi Arabia’s

intervention and the resort to violence to clear Manama’s streets, Bahrain’s King Hamad declared

that their coordinated efforts had succeeded in foiling a foreign plot against him and his Sunni

supporters. Tensions with Iran have spread across the Gulf. On April 2, Kuwaiti authorities an-

nounced they would expel several Iranian diplomats for allegedly being involved in a spy-ring.

Following a meeting of their foreign ministers in Riyadh on April 3, the Gulf Cooperation Council is-

sued a statement that they were “deeply worried about continuing Iranian meddling” and accused

Iran of plotting against the Arab monarchies. They condemned “Iran’s interference in Bahrain’s

internal affairs, in violation of international conventions.”

Iran has responded predictably to the crackdown in Bahrain and to the increasingly shrill anti-

Iranian rhetoric. In mid-March, Iran withdrew its ambassador from Bahrain and blasted Manama for

not accommodating the demands of its citizens. Iranian officials have also engaged in the escalat-

ing war of words.

Claims of Iranian meddling have been mostly unfounded until now. While some members

of Bahrain’s opposition have invoked the possibility of Iranian intervention, they have repre-

sented a marginal fringe. Instead, it is Saudi Arabia and its Arab allies that are inflaming sectarian

enmity. By projecting their anxieties regionally, Saudi Arabia has raised the stakes and provoked

a potential regional showdown with Iran. Fears of deepening sectarian tensions in the Gulf are

now being realized.

One of the potential tragedies of the current situation in the Persian Gulf is that Saudi Arabia’s

and Bahrain’s manipulation of sectarian anxieties may ultimately prove self-fulfilling. With nowhere

else to turn and little support for their cause, it is likely just a matter of time before Bahrain’s

opposition does look to Tehran for guidance. And although Iran’s leaders insist they will refrain

from intervening in the internal affairs of Saudi Arabia and Bahrain, the current crisis has created

an opening for Tehran to become more assertive and influential.

Implications for the United States

The evolving crisis in the Gulf represents a clear risk to regional security, one of the United States’

most important global strategic priorities. The United States is understandably concerned about

the prospect of greater Iranian influence and the threat it poses in the region, and yet it is two of

the United States’ closest regional allies that are leading the Gulf down the path of an enduring

crisis in which Iran’s power will almost certainly grow.

Washington should increase pressure on the governments in Riyadh and Manama to change

their current posture and find a more constructive way forward. This means dealing seriously with

the challenges of reform at home, putting an end to the violence against their own citizens, and

refraining from further manipulating and exacerbating sectarian anxieties.

© USIP 2011 • All rights reserved.

Counterrevolution in the Gulf

page 5 • PB 89 • April 15, 2011

About This Brief So far, American attempts to resolve the crisis in the Gulf have failed. Calls for restraint have been

ignored. The situation is increasingly urgent, especially given the intensification of acrimony be-

Toby C. Jones has lived and

tween Iran and its Arab neighbors. And it demands a greater American role, lest the United States

worked in Saudi Arabia and

Bahrain. Formerly the Gulf Analyst get dragged into another military conflict. The United States possesses considerable leverage in

with the International Crisis Group, the Gulf, particularly with Saudi Arabia.

he is assistant professor of Middle The most significant source of U.S. leverage comes from its security relationship with the

East history at Rutgers University.

Kingdom and the other Arab states in the Gulf. Saudi Arabia has long been a vital strategic and

He is the author of “Desert King-

dom: How Oil and Water Forged economic partner. It has also long been dependent on the United States for security assurances.

Modern Saudi Arabia” (Harvard Those assurances should not include allowing the Kingdom to risk destabilizing the region. The

University Press, 2010). The views United States should make clear to Riyadh that the American military presence in the region, and

expressed here are his own. its policy of selling weapons to regional allies, is not a cover for the Kingdom’s current reckless

strategy. Hardliners in Riyadh and Bahrain not only take the American military commitment to the

Gulf for granted, but have also turned that commitment into a source of leverage for themselves.

Should Riyadh continue on its current path, the U.S. should make clear that a reconsideration

of U.S. military commitments may be necessary. The United States has in the past and can in the

future monitor its interests in the Gulf from “over the horizon.” While it seems counterintuitive,

compelling regional actors to deal with one another on even ground will ultimately produce a

more durable political outcome. The United States’ impulse is to continue to play the balance of

power game and to seek advantages for itself and its allies. This approach is not working. In fact it

is creating new opportunities for Iran. While it may be desirable to maintain a strong relationship

with Saudi Arabia going forward, the risks of doing so may quickly outweigh the benefits.

2301 Constitution Ave., NW

Washington, D.C. 20037

USIP provides the analysis, training and

tools that prevent and end conflicts,

promotes stability and professionalizes

the field of peacebuilding.

For media inquiries, contact the office

of Public Affairs and Communications,

202.429.4725

© USIP 2011 • All rights reserved.

You might also like

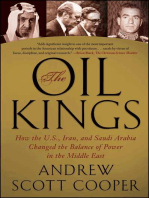

- The Oil Kings: How the U.S., Iran, and Saudi Arabia Changed the Balance of Power in the Middle EastFrom EverandThe Oil Kings: How the U.S., Iran, and Saudi Arabia Changed the Balance of Power in the Middle EastRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (10)

- So History Doesn't Forget:: Alliances Behavior in Foreign Policy of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia,1979-1990From EverandSo History Doesn't Forget:: Alliances Behavior in Foreign Policy of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia,1979-1990No ratings yet

- Saudia Arabia Vs The Arab SpringDocument17 pagesSaudia Arabia Vs The Arab SpringHisham Shehabi100% (1)

- The Golf and The Arab Rage INSDocument3 pagesThe Golf and The Arab Rage INSanon_101403622No ratings yet

- Umair Arshad Sidra Kalsoom Hamraz AshrafDocument21 pagesUmair Arshad Sidra Kalsoom Hamraz AshrafUmair GillNo ratings yet

- 3416 CombineDocument13 pages3416 CombineNabeela MushtaqNo ratings yet

- Saudi Arabia and Iran: Friend or Foe?Document15 pagesSaudi Arabia and Iran: Friend or Foe?MethmalNo ratings yet

- 3416 Combine ProjectDocument11 pages3416 Combine ProjectNabeela MushtaqNo ratings yet

- Saudi Arabia's New Strategic Paradigm by StratforDocument3 pagesSaudi Arabia's New Strategic Paradigm by StratforklatifdgNo ratings yet

- Pak Studies Presenation Group 7Document12 pagesPak Studies Presenation Group 7NizarNo ratings yet

- CFR - ExcerptsDocument9 pagesCFR - ExcerptsMrkva2000 account!No ratings yet

- The Shiites of Saudi Arabia: by Joshua TeitelbaumDocument15 pagesThe Shiites of Saudi Arabia: by Joshua TeitelbaumHassan KazimNo ratings yet

- RL33533 PDFDocument37 pagesRL33533 PDFAgnes VillaromanNo ratings yet

- Gaurding The FortressDocument3 pagesGaurding The FortresseverstaNo ratings yet

- 1990 Nasser PHDDocument819 pages1990 Nasser PHDaidee.aguilarNo ratings yet

- Al Rasheed2011Document14 pagesAl Rasheed2011sb2223No ratings yet

- Watch Out For Saudi ArabiaDocument71 pagesWatch Out For Saudi Arabiapresident007No ratings yet

- Befriending Saudi Princes: A High Price For A Dubious Alliance, Cato Policy Analysis No. 428Document15 pagesBefriending Saudi Princes: A High Price For A Dubious Alliance, Cato Policy Analysis No. 428Cato InstituteNo ratings yet

- Alfaisal Lecture at HarvardDocument10 pagesAlfaisal Lecture at HarvardTurki Al MadyNo ratings yet

- Balanta de PutereDocument4 pagesBalanta de PutereConstantin AndreiNo ratings yet

- Global 11Document2 pagesGlobal 11Azam aliNo ratings yet

- Steinberg 2014 Leading The Counter-RevolutionDocument27 pagesSteinberg 2014 Leading The Counter-RevolutionpavettaNo ratings yet

- Michale Doran - The Saudi ParadoxDocument18 pagesMichale Doran - The Saudi ParadoxJack ShieldNo ratings yet

- Saudi Arabia and Iran: The Tale of Two Media by Anne HagoodDocument18 pagesSaudi Arabia and Iran: The Tale of Two Media by Anne HagoodGhada AssafNo ratings yet

- Country Report Saudi ArabiaDocument5 pagesCountry Report Saudi ArabiaAdam Ong100% (1)

- English (P&C) (11) Subjective-2016Document4 pagesEnglish (P&C) (11) Subjective-2016Abdul MananNo ratings yet

- Saudi Arabia-Iran Contention and The Role ofDocument13 pagesSaudi Arabia-Iran Contention and The Role ofAdonay TinocoNo ratings yet

- ManzoorAli 2342 15664 3 Iran-Saudi ConflictDocument13 pagesManzoorAli 2342 15664 3 Iran-Saudi ConflictTehreem AbidNo ratings yet

- US-Saudi Relations Executive SummaryDocument2 pagesUS-Saudi Relations Executive SummaryAnuu BhattiNo ratings yet

- Saudi Arabia S Motives in The Syrian CivDocument18 pagesSaudi Arabia S Motives in The Syrian CivwefjwfuihNo ratings yet

- Meb 156Document8 pagesMeb 156PeterNo ratings yet

- SalamehDocument19 pagesSalamehCarmelo GaleanoNo ratings yet

- Lacroix - Saudi Islamists and Thearab Spring - 2014 PDFDocument35 pagesLacroix - Saudi Islamists and Thearab Spring - 2014 PDFenglishhherNo ratings yet

- Saudi Arabia and The Expansion of SalafismDocument3 pagesSaudi Arabia and The Expansion of SalafismAlly Bin AssadNo ratings yet

- Saudi FPDocument3 pagesSaudi FPwefjwfuihNo ratings yet

- Iraq's Tangled Foreign Interests and RelationsDocument44 pagesIraq's Tangled Foreign Interests and RelationsCarnegie Endowment for International PeaceNo ratings yet

- US Saudi RelationsDocument4 pagesUS Saudi RelationssamuelfeldbergNo ratings yet

- Bahraiiinnn Syiah MasyarakatDocument17 pagesBahraiiinnn Syiah MasyarakatNur wahidaNo ratings yet

- Saudi Iran RivalryDocument48 pagesSaudi Iran RivalryUsman HaiderNo ratings yet

- Fueling New World OrderDocument29 pagesFueling New World OrderZerohedgeNo ratings yet

- Saudi Arabia in The New Middle EastDocument64 pagesSaudi Arabia in The New Middle EastCouncil on Foreign Relations100% (1)

- The Saudi-Iranian Rivalry and The Future of Middle East SecurityDocument7 pagesThe Saudi-Iranian Rivalry and The Future of Middle East SecurityAsim boidyaNo ratings yet

- 13 Eval Iran Saudi StratDocument8 pages13 Eval Iran Saudi StratNoshadTechNo ratings yet

- Syed Zuhaib Waris Registration No 52303 World History Assighnment 1Document6 pagesSyed Zuhaib Waris Registration No 52303 World History Assighnment 1Syed Zohaib WarisNo ratings yet

- Saudi Iran Rapprochement Implications and Options For PakistanDocument4 pagesSaudi Iran Rapprochement Implications and Options For PakistanGM UDNo ratings yet

- Touseef Ahmad PSY. OpsDocument6 pagesTouseef Ahmad PSY. OpsTauseef AhmadNo ratings yet

- Saudi Arabia's Foreign Policy On Iran and The Proxy WarDocument10 pagesSaudi Arabia's Foreign Policy On Iran and The Proxy WarMohamed OmerNo ratings yet

- Kingdom of Saudi Arabia 1979-2009Document183 pagesKingdom of Saudi Arabia 1979-2009shiraaazNo ratings yet

- 1982 07 01 Saudi ArabiaDocument9 pages1982 07 01 Saudi ArabiaAli bin TariqNo ratings yet

- The Kingdome28099s Failed MarriageDocument4 pagesThe Kingdome28099s Failed MarriageGreg CarrNo ratings yet

- Qatar and The Recalibration of Power in The GulfDocument30 pagesQatar and The Recalibration of Power in The GulfCarnegie Endowment for International PeaceNo ratings yet

- The Kingdom and The Caliphate: Duel of The Islamic StatesDocument50 pagesThe Kingdom and The Caliphate: Duel of The Islamic StatesCarnegie Endowment for International Peace100% (1)

- Changes in The Muslim WorldDocument3 pagesChanges in The Muslim WorldirfanaliNo ratings yet

- The Precarious Ally: Bahrain's Impasse and U.S. PolicyDocument38 pagesThe Precarious Ally: Bahrain's Impasse and U.S. PolicyCarnegie Endowment for International PeaceNo ratings yet

- How Come Saudi Arabia and Iran Don't Get Along?: 18 November 2017Document3 pagesHow Come Saudi Arabia and Iran Don't Get Along?: 18 November 2017BurhanNo ratings yet

- Evolving India - Gulf RelationsDocument8 pagesEvolving India - Gulf RelationsAMAN KUMARNo ratings yet

- Geopolitics in Middle EastDocument5 pagesGeopolitics in Middle EastRajat DubeyNo ratings yet

- The Middle East ColdWarDocument9 pagesThe Middle East ColdWarLooking Glass PublicationsNo ratings yet

- 92 Reshuffling The Cards I Syrias Evolving StrategyDocument43 pages92 Reshuffling The Cards I Syrias Evolving StrategyPHDgenovaNo ratings yet

- From Bryan Turner's Article On NostalgiaDocument3 pagesFrom Bryan Turner's Article On Nostalgiaadso12No ratings yet

- Feeling at Home: Some Reºections On Muslims in Europe: Bhikhu ParekhDocument35 pagesFeeling at Home: Some Reºections On Muslims in Europe: Bhikhu Parekhadso12No ratings yet

- Crafting 18420 1 StylePBDocument2 pagesCrafting 18420 1 StylePBadso12No ratings yet

- Freud The Schreber CaseDocument2 pagesFreud The Schreber Caseadso12100% (1)

- MLA Citation Style: Documenting Sources in The TextDocument4 pagesMLA Citation Style: Documenting Sources in The Textadso12No ratings yet

- Dictionary of Literary Biography IndexDocument3 pagesDictionary of Literary Biography Indexadso12No ratings yet

- Halliday - Orientalism and Its CriticsDocument20 pagesHalliday - Orientalism and Its Criticsadso12No ratings yet

- Brooks Reading For The Plot PrefaceDocument4 pagesBrooks Reading For The Plot Prefaceadso12No ratings yet

- Rowe - The Cultural Politics of The New American StudiesDocument236 pagesRowe - The Cultural Politics of The New American Studiesmplateau100% (1)

- Metempsychosis in UlyssesDocument48 pagesMetempsychosis in Ulyssesadso12100% (1)

- Don DeLillo's "In The Ruins of The Future"Document15 pagesDon DeLillo's "In The Ruins of The Future"adso12No ratings yet

- Landfill TutorialDocument31 pagesLandfill Tutorialadso12No ratings yet

- Psychology's Magician On JungDocument29 pagesPsychology's Magician On Jungadso12No ratings yet

- IntroductionDocument3 pagesIntroductionadso12No ratings yet

- Blank BOLDocument1 pageBlank BOLRaymond DavisNo ratings yet

- In The Supreme Court of IndiaDocument13 pagesIn The Supreme Court of IndiaMahima ChauhanNo ratings yet

- Case 67 - Prince Transport v. Garcia, G.R. No. 167291, January 12, 2011Document3 pagesCase 67 - Prince Transport v. Garcia, G.R. No. 167291, January 12, 2011bernadeth ranolaNo ratings yet

- Assignment List 1st YearDocument1 pageAssignment List 1st YearRitesh TalwadiaNo ratings yet

- Country Risk AnalysisDocument19 pagesCountry Risk Analysisamit1002001No ratings yet

- Demand Letter Sample For UAEDocument1 pageDemand Letter Sample For UAEDinkar Joshi0% (1)

- Landscape Irrigation Systems CommissioningDocument1 pageLandscape Irrigation Systems CommissioningHumaid ShaikhNo ratings yet

- Nolo Press A Legal Guide For Lesbian and Gay Couples 11th (2002)Document264 pagesNolo Press A Legal Guide For Lesbian and Gay Couples 11th (2002)Felipe ToroNo ratings yet

- Use of Multimodal Text To Address Gender Equality Fact Sheet (Group9)Document1 pageUse of Multimodal Text To Address Gender Equality Fact Sheet (Group9)Daniel GuerreroNo ratings yet

- The Muslim Family Laws Ordinance 1961Document5 pagesThe Muslim Family Laws Ordinance 1961Model Court SahiwalNo ratings yet

- DAVIS v. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA - Document No. 4Document3 pagesDAVIS v. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA - Document No. 4Justia.comNo ratings yet

- The Assassination of Herbert Chitepo Texts and Politics in ZimbabweDocument160 pagesThe Assassination of Herbert Chitepo Texts and Politics in ZimbabweMandel Mach100% (3)

- Review Mukhtasar Al-QuduriDocument2 pagesReview Mukhtasar Al-QuduriMansur Ali0% (1)

- Market Access - 2 - Non-Tariff Measures - ExtendedDocument168 pagesMarket Access - 2 - Non-Tariff Measures - ExtendedNguyen Tuan AnhNo ratings yet

- The Idea of Pakistan (Stephen Cohen) PDFDocument396 pagesThe Idea of Pakistan (Stephen Cohen) PDFRana Sandrocottus100% (1)

- Agreement: Supply of Water Through Alternate Source (Reverse Osmosis Plant)Document3 pagesAgreement: Supply of Water Through Alternate Source (Reverse Osmosis Plant)Neha EssaniNo ratings yet

- 2nd Draft of The Environmental CodeDocument162 pages2nd Draft of The Environmental CodeThea Baltazar100% (2)

- Form B - Data Entry Operator (BPS-12)Document5 pagesForm B - Data Entry Operator (BPS-12)Shahjahan AfridiNo ratings yet

- NGO DarpanDocument13 pagesNGO DarpanHemant DhandeNo ratings yet

- Commercial Dispatch Eedition 3-5-21Document16 pagesCommercial Dispatch Eedition 3-5-21The DispatchNo ratings yet

- Thesis Normalisation of Street Harassment Thesis PDFDocument87 pagesThesis Normalisation of Street Harassment Thesis PDFArlette Danielle Roman AlmanzarNo ratings yet

- Consti CasesDocument5 pagesConsti CasesVIA ROMINA SOFIA VILLA VELASCONo ratings yet

- Family Planning and IslamDocument8 pagesFamily Planning and IslamFarrukhRazzaqNo ratings yet

- Academics EconomicsDocument3 pagesAcademics EconomicsNitin PhartyalNo ratings yet

- UKRep Main Roles, 2010-20Document5 pagesUKRep Main Roles, 2010-20Matt BevingtonNo ratings yet

- Omondi-Sex in KenyaDocument20 pagesOmondi-Sex in KenyaEm LENo ratings yet

- Orendain vs. Trusteedhip of The Estate of Doña Margarita Rodriguez DigestDocument2 pagesOrendain vs. Trusteedhip of The Estate of Doña Margarita Rodriguez DigestJoey PastranaNo ratings yet

- Complaint Against The Police: Your Details (Complainant)Document5 pagesComplaint Against The Police: Your Details (Complainant)Francesca MasonNo ratings yet

- On Civil DisobedienceDocument1 pageOn Civil Disobediencexardas121dkNo ratings yet

- GR No. 125469Document5 pagesGR No. 125469Karen Gina DupraNo ratings yet