Professional Documents

Culture Documents

BJHJH

Uploaded by

Nadica Vermezovic0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

62 views3 pagesIn our cognitive motivational process model we assume that initial motivation affects performance via motivation during learning and learning strategies. Initial motivation with its four factors challenge, probability of success, interest, and anxiety was measured with the QCM. As an indicator for the functional state we assessed flow with the FKS.

Original Description:

Original Title

bjhjh

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentIn our cognitive motivational process model we assume that initial motivation affects performance via motivation during learning and learning strategies. Initial motivation with its four factors challenge, probability of success, interest, and anxiety was measured with the QCM. As an indicator for the functional state we assessed flow with the FKS.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

62 views3 pagesBJHJH

Uploaded by

Nadica VermezovicIn our cognitive motivational process model we assume that initial motivation affects performance via motivation during learning and learning strategies. Initial motivation with its four factors challenge, probability of success, interest, and anxiety was measured with the QCM. As an indicator for the functional state we assessed flow with the FKS.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 3

hnvjhv

Motivational Effects on Self-Regulated Learning

with Different Tasks

Regina Vollmeyer & Falko Rheinberg

Published online: 17 October 2006

# Springer Science + Business Media, Inc. 2006

Abstract In our cognitive motivational process model (Vollmeyer & Rheinberg,

Zeitschrift

für Pädagogische Psychologie, 12:11–23, 1998) we assume that initial motivation affects

performance via motivation during learning and learning strategies. These variables are

also

central for self-regulation theories (e.g., M. Boekaerts, European Psychologist, 1:100

–122,

1996). In this article we discuss methods with which the model can be tested. Initial

motivation with its four factors challenge, probability of success, interest, and

anxiety was

measured with the Questionnaire on Current Motivation (QCM; Rheinberg, Vollmeyer, &

Burns, Diagnostica, 47:57– 66, 2001). As an indicator for the functional state we

assessed

flow with the FKS (Rheinberg, Vollmeyer, & Engeser, Diagnostik von Motivation und

Selbstkonzept [Diagnosis of Motivation and Self-Concept], Hogrefe, Göttingen, Germany,

261–279, 2003). We also used different tasks, including a linear system, a hypermedia

program, and university-level classes. In general, our methods are valid and with them

we

found support for our model.

Keywords Flow-experience . Motivation . Performance . Self-regulation . Strategies

Introduction

Models of self-regulated learning (Boekaerts, 1996; Pintrich, 2000; Zimmerman, 2000)

describe how learners use cognitive strategies, metacognition, volition, and motivation

to

Educ Psychol Rev (2006) 18:239–253

DOI 10.1007/s10648-006-9017-0

This research was supported by two grants (Vo 514-5, 514-10) from the German Research

Foundation (DFG)

to Regina Vollmeyer and Falko Rheinberg.

R. Vollmeyer (*)

Institut für Pädagogische Psychologie, Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität Frankfurt,

Postfach 11 19 32, 60054 Frankfurt am Main, Germany

e-mail: R.Vollmeyer@paed.psych.uni-frankfurt.de

F. Rheinberg

Institut für Psychologie, Universität Potsdam, Potsdam, Germany

monitor their learning process. They specify which variables researchers should take

into

account to understand how self-regulated learners learn. Although there are several

models,

the methods to operationalize the models’ variables differ between researchers. In this

article our first aim is to present our cognitive-motivational process model and the

methods

to study the model’s assumptions. The second aim is to present results gained with

these

methods. Of course, we also need to address the methods’ limits.

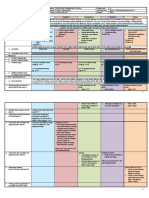

The Cognitive-Motivational Process Model

Similar to models of self-regulated learning Vollmeyer and Rheinberg (1998, 2000;

Rheinberg, Vollmeyer, & Rollett, 2000, see Fig. 1) developed their

cognitive-motivational

process model. The aim of the model was (1) to specify factors of initial motivation

(theoretical assumptions and results are presented in the section “Initial

motivation”), (2) to

collect possible mediators for the influence of initial motivation on performance

(theoretical

assumptions are presented in the section “Mediators for the influence of initial

motivation

on performance”), and finally (3) to emphasize different learning outcomes. In this

article

we will focus on how we measured these different process variables and we discuss the

quality of our measures. In addition, we present studies that support our model (in

Page 1

hnvjhv

section

“A test of the model derived from the cognitive-motivational process model”).

Initial Motivation

In the models of self-regulated learning mentioned above, motivation covers several

motivational concepts. For example, Zimmerman (2000) refers to self-motivation beliefs

(this may include concepts such as self-efficacy and outcome expectations (Bandura,

1997),

intrinsic interest/value (Deci, 1975) and goal-orientation (Dweck & Leggett, 1988;

Nicholls,

1984)). Pintrich (2000) mentioned perceptions of task difficulty (similar to

probability of

success; Atkinson, 1957) and interest (Krapp, Hidi, & Renninger, 1992). The concepts of

task difficulty and interest are also central in Wigfield and Eccles’ (2002)

expectancy-value

model. On the basis of these models and on our own research we postulated four

important

factors of initial motivation: (1) probability of success, (2) anxiety, (3) interest,

and (4)

challenge. As we decided to define these four factors as initial motivation we

developed a

questionnaire (for items of the Questionnaire on Current Motivation [QCM], Rheinberg,

Vollmeyer, & Burns, 2001, see Appendix 1). In the next sections we describe the

theoretical

assumptions followed by a discussion of the questionnaire (i.e., quality and

motivational

patterns).

Initial Motivation Mediators Learning Outcome

probability of success duration/frequency knowledge

anxiety systematic transfer

strategies

interest motivational state

challenge functional state

learning

Fig. 1 The cognitive-motivational process model.

240 Educ Psychol Rev (2006) 18:239–253

Probability of success is a factor discussed as early as the models of Lewin, Dembo,

Festinger, and Sears (1944), Atkinson (1957, 1964), and is also part of newer theories

such

as Bandura (1997), Anderson (1993) and Wigfield and Eccles (2002). Learners at least

implicitly calculate the probability of success in that they take into account their

ability and

the perceived difficulty of the task. This concept could be even more precisely

specified as

learners’ belief that they can succeed in the task (for personal agency beliefs see

Ford,

1992; for self-efficacy see Pajares, 1997; for control theories see Skinner, 1996).

However,

for our purpose it was sufficient to formulate a general probability-of-success factor.

The second factor is anxiety, which can be partly interpreted as fear of failure in a

specific situation (Atkinson, 1957, 1964). However, this factor is not necessarily the

opposite of high probability of success, as it can be high for learners who are in a

social

situation in which they do not want to fail and try hard to avoid failure even though

they

expect to succeed. Thus, anxiety incorporates the negative incentive of failure.

The third factor is interest. For learning, the topic of the learning material is

important as

has been shown in theories of interest (e.g., Krapp, Hidi, & Renninger, 1992). If

learners are

interested they have positive affects and positive evaluations regarding the topic.

The last factor we regarded as important is challenge. This factor assesses whether

learners accept the situation as an achievement situation in which they want to have

success. If they want to have success then the learning situation gains importance

(Importance is a subjective task value component from the expectancy-value model by

Wigfield & Eccles, 2002).

Page 2

hnvjhv

Quality of the measurement of the four factors Before we report how initial motivation

affects the learning process we want to give some details about the motivational

factors’

quality. As mentioned above we constructed a questionnaire (QCM) that should capture

learners’ current motivation after they were instructed to do a task and before they

really

started. Because current motivation changes over tasks and time we did not expect a

stable

measure, on the contrary, motivation has to change depending on the characteristics of

the

task.

Page 3

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Cultural Centre SynopsisDocument12 pagesCultural Centre SynopsisAr Manpreet Prince50% (2)

- Samples English Lessons Through LiteratureDocument233 pagesSamples English Lessons Through LiteratureEmil Kosztelnik100% (1)

- Trends, Networks and Critical Thinking Skills in The 21st Century - TOPIC OUTLINEDocument3 pagesTrends, Networks and Critical Thinking Skills in The 21st Century - TOPIC OUTLINERodrick Sonajo Ramos100% (1)

- Problems Encountered by Teachers in The Teaching-Learning Process: A Basis of An Action PlanDocument20 pagesProblems Encountered by Teachers in The Teaching-Learning Process: A Basis of An Action PlanERIKA O. FADEROGAONo ratings yet

- Xue Bin (Jason) Peng: Year 2, PHD in Computer ScienceDocument3 pagesXue Bin (Jason) Peng: Year 2, PHD in Computer Sciencelays cleoNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Template For CollegeDocument4 pagesResearch Paper Template For Collegec9k7jjfk100% (1)

- IPCRF Form TeachersDocument9 pagesIPCRF Form TeachersrafaelaNo ratings yet

- 8th Merit List DPTDocument6 pages8th Merit List DPTSaleem KhanNo ratings yet

- Heroes Pioneers and Role Models of Trinidad and Tobago PDFDocument208 pagesHeroes Pioneers and Role Models of Trinidad and Tobago PDFsno-kone0% (1)

- Q3 SLEM WEEK10 GROUPC Edited and CheckedDocument5 pagesQ3 SLEM WEEK10 GROUPC Edited and CheckedSELINA GEM ESCOTENo ratings yet

- Instructional LeadershipDocument45 pagesInstructional LeadershipJESSIE CUTARA67% (3)

- Free E Book India 2011Document414 pagesFree E Book India 2011RameshThangarajNo ratings yet

- SACC Booklet - Annual Gala 2018Document28 pagesSACC Booklet - Annual Gala 2018Sikh ChamberNo ratings yet

- Caregiving Las Week 2Document16 pagesCaregiving Las Week 2Florame OñateNo ratings yet

- 台灣學生關係子句習得之困難Document132 pages台灣學生關係子句習得之困難英語學系陳依萱No ratings yet

- Final Professional M.B.B.S. Examination of July 2021: Select Student TypeDocument4 pagesFinal Professional M.B.B.S. Examination of July 2021: Select Student Typeasif hossainNo ratings yet

- My Final NagidDocument36 pagesMy Final NagidRenalene BelardoNo ratings yet

- TeambuildingDocument18 pagesTeambuildingsamir2013100% (1)

- Lesson 16 - Designing The Training CurriculumDocument80 pagesLesson 16 - Designing The Training CurriculumCharlton Benedict BernabeNo ratings yet

- Bopps - Lesson Plan Surv 2002Document1 pageBopps - Lesson Plan Surv 2002api-539282208No ratings yet

- Parameter For Determining Cooperative Implementing BEST PRACTICESDocument10 pagesParameter For Determining Cooperative Implementing BEST PRACTICESValstm RabatarNo ratings yet

- Random Thoughts of A Random TeenagerDocument10 pagesRandom Thoughts of A Random Teenagervishal aggarwalNo ratings yet

- Chapter1 Education and SocietyDocument13 pagesChapter1 Education and SocietyChry Curly RatanakNo ratings yet

- Assignment - ReflectionDocument6 pagesAssignment - ReflectionAkash HolNo ratings yet

- Curriculum and the Teacher's RoleDocument11 pagesCurriculum and the Teacher's RoleAudremie DuratoNo ratings yet

- Joseph Sereño's Criminology ProfileDocument2 pagesJoseph Sereño's Criminology ProfileRoelineRosalSerenoNo ratings yet

- Accounting Modular LearningDocument21 pagesAccounting Modular LearningClarissa Rivera VillalobosNo ratings yet

- DLL Epp6-Entrep q1 w3Document3 pagesDLL Epp6-Entrep q1 w3Kristoffer Alcantara Rivera50% (2)

- Be Form 2 School Work PlanDocument3 pagesBe Form 2 School Work PlanJOEL DAENNo ratings yet

- Sehrish Yasir2018ag2761-1-1-1Document97 pagesSehrish Yasir2018ag2761-1-1-1Rehan AhmadNo ratings yet