Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Artist As Worker

Uploaded by

Michelle GreerOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Artist As Worker

Uploaded by

Michelle GreerCopyright:

Available Formats

Reviews

The Artist as Worker

Dominic Rahtz

Art Workers: Radical Practice in the Vietnam War

Era by Julia Bryan-Wilson, Berkeley, CA: University of

California Press, 2009, 296 pp., 12 col. and 91 b. & w.

illus., £27.95

An obvious contradiction haunts this book. On the one

hand, the Art Workers’ Coalition (AWC), established

spontaneously as a group fighting for artists’ rights in

New York in early 1969, was resolutely collective in

its mode of action and ‘non-aesthetic’ (as one of its

participants, Lucy Lippard, put it) in its concerns.1 On

the other hand, the central claim of the book is that

certain participants in the group, such as Carl Andre,

Robert Morris, Lippard and Hans Haacke, incorporated

the identity of the ‘art worker’ into their individual

artistic (and writing) practices. Is this contradiction,

of which Julia Bryan-Wilson is doubtlessly aware,

to be regarded as historically constitutive or is it a

consequence of the art-historical narrative itself?

The series of chapters on individuals that comprises

the book is conventionally academic, but here it is

an approach that contains the danger of concealing

the idea of the ‘art worker’ as the figure of a political

impulse to collectivity. And yet the focus on individuals

also reveals experiences of the incommensurability

of art work and political action that are historically

significant and continue to be of relevance, providing

a reflection from another time on more recent shifts

in the character of art towards collaboration and the

opening out of art to other social practices.

In Art Workers, it is the definition of art as a form

of work, or labour, that determines the relationship

between art and politics. Although the historical

moment of the AWC, and the contiguous event of

the 1970 New York Art Strike, was relatively brief

(the coalition was dissolved in 1971), the projection

of the condition of art as work is related to a much

broader historical shift – that from industrial to post-

industrial society, or from material to immaterial

labour. This shift drives the narrative plot of the book.

Both the work and the political attitude of the first

artist that Bryan-Wilson considers, Carl Andre, are

characterized by a nostalgia for the industrial mode

of production that determined the nature of his

materials (especially the floor works made from metal

© Association of Art Historians 2011 218

Reviews

plates), as well as for a more traditional Marxism – last chapter, the material mode of work nostalgically

Andre was apparently responsible for insisting on invoked by Andre has been replaced by the immaterial

the term ‘worker’ in the AWC – which was at the or intellectual labour associated with information. It is

time being displaced by the more spontaneous and here that the direction of influence between art work

individualistic modes of political action associated and political agency also changes. Whereas Andre had

with the New Left. The chapter on Robert Morris is taken a romanticized Marxist conception of the worker

initially concerned with his 1970 exhibition at the into the AWC, Haacke, according to Bryan-Wilson,

Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, in took the political mode of information-as-exposé

which large-scale construction materials were kept in practised by the AWC into art works such as his famous

a state of processual change by Morris, working with (and censored at the time) Shapolsky et al. Manhattan Real-

a team of construction workers. This work, as Bryan- Estate Holdings:A Real-Time Social System, as of May 1, 1971

Wilson writes, represented a dematerialization of the (1971). Bryan-Wilson treats the efforts at research that

commodity-character of the work of art at the same went into this canonical work of conceptual art as an

time that it materialized the labour of the artist. But instance of immaterial labour, thereby associating what

the real crux of the chapter comes with the suddenly Herbert Marcuse, in An Essay on Liberation (1969), called

compromised identity of artist and worker due to the the ‘dematerialization of labour’ with what Lippard

event, exactly contemporaneous with the Whitney called, in relation to process and conceptual art, the

exhibition, of the so-called ‘hard-hat riots’, in which ‘dematerialization of the art object’.2

construction workers in Detroit violently broke up The reference to Marcuse is apposite here since

an antiwar demonstration thereby allying themselves it is from him that the phrase ‘radical practice’ in

with the conservative, patriotic stance of the Nixon the title of the book derives, and yet the relationship

administration. Subsequent to this event, Morris closed established between Marcuse and art in the late 1960s

his exhibition at the Whitney early in a gesture of is ambiguous in revealing ways. The encounter between

support for the spontaneous and widespread strikes German critical theory and American post-minimalism

taking place throughout the United States in protest in the New York art world (registered directly from

at the war in Vietnam, a ‘strike’ that led to the more Marcuse’s side in the lectures he gave at the School of

general action, arising out of the AWC, of the New York Visual Arts in New York and the Guggenheim Museum

Art Strike against Racism, War and Repression of May in the late 1960s) 3 is a remarkable episode that

1970. Bryan-Wilson suggests, however, that Morris’s deserves more attention than it has been given hitherto

‘art strike’ was also a matter of political expediency, in the field of contemporary art history. Marcuse

the consequence of an encounter between two expressed pessimism regarding the political claims

incompatible figures of the worker, one reactionary in associated with art of the late 1960s that aimed at a

a political register and the other radical in an artistic negation of artistic form, arguing that form constituted

register. the only realm in which a reality different from existing

In the case of Lucy Lippard, her relationship to reality could take shape. In a way that does not support

the epithet ‘worker’ was complicated by the nature of the thesis of Art Workers particularly well, the chapter on

her activities as an art critic and curator, which were art in Marcuse’s Counterrevolution and Revolt from which

seen by her as instances of the ‘housework’ of art, Bryan-Wilson draws her definition of ‘radical practice’

and so as implicitly gendered. Although this chapter is essentially an argument for the autonomy of art.4 The

describes Lippard’s gradual move towards a more only way that art can be defined as a ‘radical practice’ is

explicit feminism, it also points to a narrowness in within the bounds of art. Thus the claims to ‘reality’ in

the conception of labour in the ‘art worker’ which art, in both materials and action, by Andre, Morris and

was partially responsible for the fragmentation of the Haacke would have been judged too literal by Marcuse,

AWC into smaller groups such as the Ad Hoc Women and hence self-defeating in political terms. Bryan-

Artists’ Committee (of which Lippard was a member) Wilson’s appropriation of the phrase ‘radical practice’

and Women Artists in Revolution. The other main to describe the more heteronomous performative realm

thread in this chapter, that dealing with the ‘intellectual in which the ‘art worker’ constituted a rehearsal of the

labour’ of writing and the relationship between art possible relationships between art work and political

and information, is picked up again in relation to art action sits very uneasily with Marcuse’s views on art

practice in the discussion of Hans Haacke. By this during this period. The extent to which Art Workers

© Association of Art Historians 2011 219

Reviews

achieves historical distance from such contradictions

is open to question, but that they are raised in the

treatment of the historical material makes the book one

of the first sustained attempts to describe the social and

political character of the art of the 1960s.

Notes

1 Lucy Lippard, ‘The Art Workers’ Coalition: Not a history’, Studio

International, 180: 927, November 1970, 174.

2 Herbert Marcuse, An Essay on Liberation, London, 1969, 49; Lucy Lippard

and John Chandler, ‘The dematerialization of art’, Art International, 12: 2,

February 1968, 31–6.

3 See Herbert Marcuse, ‘Art in the one-dimensional society’, Arts Magazine,

41: 7, May 1967, 26–31 and Herbert Marcuse, ‘Art as form of reality’,

New Left Review, 74, July–August 1972, 51–8.

4 Herbert Marcuse, Counterrevolution and Revolt, London, 1972, 79–128.

© Association of Art Historians 2011 220

You might also like

- Breaking Ground: Art Modernisms 1920-1950, Collected Writings Vol. 1From EverandBreaking Ground: Art Modernisms 1920-1950, Collected Writings Vol. 1No ratings yet

- Art Versus Work 180310Document2 pagesArt Versus Work 180310IvaNo ratings yet

- A People's Art History of the United States: 250 Years of Activist Art and Artists Working in Social Justice MovementsFrom EverandA People's Art History of the United States: 250 Years of Activist Art and Artists Working in Social Justice MovementsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Classicism of the Twenties: Art, Music, and LiteratureFrom EverandClassicism of the Twenties: Art, Music, and LiteratureRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Gavin Grindon Surrealism Dada and The Refusal of Work Autonomy Activism and Social Participation in The Radical Avantgarde 1Document18 pagesGavin Grindon Surrealism Dada and The Refusal of Work Autonomy Activism and Social Participation in The Radical Avantgarde 1jmganjiNo ratings yet

- Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of SpectatorshipFrom EverandArtificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of SpectatorshipRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (12)

- Marx and IdeologyDocument3 pagesMarx and IdeologyhiNo ratings yet

- Modernism at the Barricades: aesthetics, Politics, UtopiaFrom EverandModernism at the Barricades: aesthetics, Politics, UtopiaNo ratings yet

- Constructed Situations: A New History of the Situationist InternationalFrom EverandConstructed Situations: A New History of the Situationist InternationalRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- The Beauty of a Social Problem: Photography, Autonomy, EconomyFrom EverandThe Beauty of a Social Problem: Photography, Autonomy, EconomyNo ratings yet

- Conceptual Art and Feminism - Martha Rosler, Adrian Piper, Eleanor Antin, and Martha WilsonDocument7 pagesConceptual Art and Feminism - Martha Rosler, Adrian Piper, Eleanor Antin, and Martha Wilsonrenata ruizNo ratings yet

- Artist/Critic?Document4 pagesArtist/Critic?AlexnatalieNo ratings yet

- Hungarian Art: Confrontation and Revival in the Modern MovementFrom EverandHungarian Art: Confrontation and Revival in the Modern MovementNo ratings yet

- The Struggle Against Naturalism: Soviet Art From The 1920s To The 1950sDocument14 pagesThe Struggle Against Naturalism: Soviet Art From The 1920s To The 1950sმირიამმაიმარისიNo ratings yet

- Grindon - 2011 - Surrealism, Dada, and The Refusal of Work Autonomy, Activism, and Social Participation in The Radical Avant-garde-AnnotatedDocument18 pagesGrindon - 2011 - Surrealism, Dada, and The Refusal of Work Autonomy, Activism, and Social Participation in The Radical Avant-garde-AnnotatedcristinapoptironNo ratings yet

- The Guarantor of Chance-Surrealism's Ludic Practices by Susan LaxtonDocument17 pagesThe Guarantor of Chance-Surrealism's Ludic Practices by Susan LaxtonArkava DasNo ratings yet

- Conceptual Art and Feminism - Martha Rosler, Adrian Piper, Eleanor Antin, and Martha WilsonDocument8 pagesConceptual Art and Feminism - Martha Rosler, Adrian Piper, Eleanor Antin, and Martha Wilsonam_carmenNo ratings yet

- Buchloh - Formalism and HistoricityDocument17 pagesBuchloh - Formalism and HistoricityPol Capdevila100% (2)

- The 10 Essays That Changed Art Criticism Forever - Art For Sale - ArtspaceDocument27 pagesThe 10 Essays That Changed Art Criticism Forever - Art For Sale - Artspaceclaxheugh100% (2)

- Art of The Socialist PastDocument2 pagesArt of The Socialist PastandrejkirilenkoNo ratings yet

- Artist Ethnographer H.fosterDocument18 pagesArtist Ethnographer H.fosterAlessandra FerriniNo ratings yet

- The Platypus Review, 45 - April 2012 (Reformatted For Reading Not For Printing)Document5 pagesThe Platypus Review, 45 - April 2012 (Reformatted For Reading Not For Printing)Ross WolfeNo ratings yet

- Marxism and Modernism: An Historical Study of Lukacs, Brecht, Benjamin, and AdornoFrom EverandMarxism and Modernism: An Historical Study of Lukacs, Brecht, Benjamin, and AdornoRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (4)

- Warren Carter Renew Marxist Art History PDFDocument1,031 pagesWarren Carter Renew Marxist Art History PDFShaon Basu100% (3)

- The Origins of Feminist ArtDocument17 pagesThe Origins of Feminist ArtDaanJimenezNo ratings yet

- Conceptualism and FeminismDocument8 pagesConceptualism and FeminismOlesia ProkopetsNo ratings yet

- Linda BenglysDocument14 pagesLinda BenglysClaudiaRomeroNo ratings yet

- Abstract ExpressionismDocument11 pagesAbstract ExpressionismH MAHESHNo ratings yet

- Marxism and the History of Art: From William Morris to the New LeftFrom EverandMarxism and the History of Art: From William Morris to the New LeftRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Late Modernism: Art, Culture, and Politics in Cold War AmericaFrom EverandLate Modernism: Art, Culture, and Politics in Cold War AmericaNo ratings yet

- Modernist Abstraction, Anarchist Anti Militarism, and WarDocument39 pagesModernist Abstraction, Anarchist Anti Militarism, and WarAtosh KatNo ratings yet

- The Aesthetics of LeRoi Jones / Amiri Baraka: The Rebel PoetFrom EverandThe Aesthetics of LeRoi Jones / Amiri Baraka: The Rebel PoetNo ratings yet

- Distant Early Warning: Marshall McLuhan and the Transformation of the Avant-GardeFrom EverandDistant Early Warning: Marshall McLuhan and the Transformation of the Avant-GardeNo ratings yet

- J.borda - Ba ThesisDocument28 pagesJ.borda - Ba ThesisCecilia BarretoNo ratings yet

- After the End of Art: Contemporary Art and the Pale of History - Updated EditionFrom EverandAfter the End of Art: Contemporary Art and the Pale of History - Updated EditionRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (26)

- Gale Researcher Guide for: The Arts and Scientific Achievements between the WarsFrom EverandGale Researcher Guide for: The Arts and Scientific Achievements between the WarsNo ratings yet

- How New York Stole the Idea of Modern ArtFrom EverandHow New York Stole the Idea of Modern ArtRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (13)

- Differences Between Modernism and PostmodernismDocument20 pagesDifferences Between Modernism and PostmodernismShashank KUmar Rai BhadurNo ratings yet

- Action PaintingDocument4 pagesAction PaintingDavid BonteNo ratings yet

- Structural Criticism: We Started This Course With A Discussion of What Art Is. That Discussion WasDocument3 pagesStructural Criticism: We Started This Course With A Discussion of What Art Is. That Discussion Waslara camachoNo ratings yet

- Cooper, IvyDocument11 pagesCooper, IvyMarshall BergNo ratings yet

- Anna Dezeuze - Street Works, Borderline Art, DematerialisationDocument36 pagesAnna Dezeuze - Street Works, Borderline Art, DematerialisationIla FornaNo ratings yet

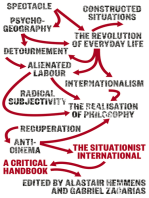

- The Situationist International: A Critical HandbookFrom EverandThe Situationist International: A Critical HandbookAlastair HemmensNo ratings yet

- Blooms Bury - Fry - C Bell - & Chinese ArtDocument43 pagesBlooms Bury - Fry - C Bell - & Chinese ArtpillamNo ratings yet

- Howard Singerman - The Myth of Criticism in The 1980sDocument16 pagesHoward Singerman - The Myth of Criticism in The 1980sHeimNo ratings yet

- Konkol Poetryand AnarchismDocument9 pagesKonkol Poetryand AnarchismhenrikoanandaputraNo ratings yet

- Anna Chave - Minimalism and The Rhetoric of PowerDocument23 pagesAnna Chave - Minimalism and The Rhetoric of PowerEgor SofronovNo ratings yet

- Konko Poetry and AnarchismDocument9 pagesKonko Poetry and AnarchismDan CapelNo ratings yet

- Iconographic Analysis - Historical PDFDocument9 pagesIconographic Analysis - Historical PDFStuart OringNo ratings yet

- The Room Trick. Sound As SiteDocument12 pagesThe Room Trick. Sound As SiteManuel CirauquiNo ratings yet

- Giedion, Sert, Leger: Nine Points On MonumentalityDocument5 pagesGiedion, Sert, Leger: Nine Points On MonumentalityManuel CirauquiNo ratings yet

- Complete Works of Lucian of SamosataDocument363 pagesComplete Works of Lucian of SamosataManuel CirauquiNo ratings yet

- Manuel Cirauqui, "Beyond Translation"Document8 pagesManuel Cirauqui, "Beyond Translation"Manuel CirauquiNo ratings yet

- Gerrit Henry, "Views From The Studio," ARTnews, 1976Document3 pagesGerrit Henry, "Views From The Studio," ARTnews, 1976Manuel CirauquiNo ratings yet

- Alan Beck, "Is Radio Blind or Invisible? A Call For A Wider Debate On Listening-In"Document20 pagesAlan Beck, "Is Radio Blind or Invisible? A Call For A Wider Debate On Listening-In"Manuel CirauquiNo ratings yet

- Manuel Cirauqui, "Subjunctive Reenacted" JanMot Newspaper 2011Document8 pagesManuel Cirauqui, "Subjunctive Reenacted" JanMot Newspaper 2011Manuel CirauquiNo ratings yet

- PLoS ONE - Disease Dynamics in A Specialized Parasite of Ant SocietiesDocument16 pagesPLoS ONE - Disease Dynamics in A Specialized Parasite of Ant SocietiesManuel CirauquiNo ratings yet

- The Stratagem - The Stratagem and Other StoriesDocument9 pagesThe Stratagem - The Stratagem and Other StoriesManuel CirauquiNo ratings yet

- Tate Papers Issue 14 Autumn 2010 - Anna LovattDocument13 pagesTate Papers Issue 14 Autumn 2010 - Anna LovattManuel CirauquiNo ratings yet

- Fredric Jameson, ValencesDocument624 pagesFredric Jameson, ValencesIsidora Vasquez LeivaNo ratings yet