Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Basics of The Fly

Uploaded by

lilthumbOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Basics of The Fly

Uploaded by

lilthumbCopyright:

Available Formats

Th e Ba si c s of the Willamette Fly Offense

n behalf of the entire offensive staff at Willamette University, Glen Fowles (offensive line), Chuck Pinkerton (runningbacks), and Josh Scott (receivers), it is an honor to contribute to the 2004 AFCA Summer Manual. I am appreciative to all the coaches over the years that have contributed to my knowledge as a football coach. At Willamette University, we take great pride in running our version of the fly offense. The hallmarks of the fly offense are speed and deception. We feel this system has helped us be competitive in a tough league and at a highly academic university. We are committed to having a strong running game. For the past nine years, we have been able to average over five yards a carry each season. I show these numbers to highlight the long term effectiveness of our running game. We feel that we play against some of the finest Division III defenses in the nation in the Northwest conference and have to be sound to move the ball. Willamette Fly Offense Rushing Average Year Rushing Avg. Rushing Avg. Per game Per carry 1995 287.2 5.7 1996 259.7 5.2 1997 281.4 5.4 1998 304.3 5.2 1999 322.2 6.0 2000 252.8 5.1 2001 265.7 5.3 2002 350.0 6.2 2003* 345.5 6.1 *-No. 21 in total offense (439.6 ypg). It is virtually impossible to explain an entire offensive system in one article. In this article, I will attempt to explain the overall teaching philosophy behind our system. Next I will discuss the basic fundamentals of the signature play in our offense, the fly sweep. Every coaching staff in America wrestles with the dilemma of how many plays are too many. The ability to practice and execute your offense dictates a finite number of plays. Being both a head coach and an assistant coach at times in my career, I have participated in many spirited discussions about how many plays our team should have. I believe that the best system is easy for your team to execute and hard for the opponent to stop. In teaching our offense, we try and stay away from the idea

of plays. Instead, we use three different styles of teaching our run offense. The Linemen Learn Rules The rules are words describing who to block. When all the plays weve run over the years are boiled down, we really only have about eight rules for the lineman to learn. There are many styles of offensive line rules, and I dont think one style is bet ter than another. The key is to have a concise, simple way to block man, zone, short trap, long trap, cross blocks, down blocks and reach blocks. The Receivers Learn Concepts We teach concepts to the receivers in the passing game and the run game. Our day one run game rules for our receivers are; 1. Play away from me (Block corner on me). 2. Play up the middle (Block closest safety, no safety, closest corner). 3. Play to me (Crack No. 2/force defender). The Backs Learn Paths Each play requires the back to run to a certain spot and find daylight. The play name is the path the back receiving the ball will run. In our two back offense, the back not receiving the ball will either get a path name or have an option of choosing a path to run. We have paths for each spot a back could align for us in our formations. Here is a sample of a few of our paths.

Diagram 1

Diagram 2

This system creates a lot of variation. By mixing and matching back paths and blocking rules, you can quickly amass a

Diagram 3

Diagram 4

wide variety of plays. I have found that coaches and players do not always feel comfortable with new plays, but have great comfort with wrinkles described and taught with day one terminology. The base play in the fly offense is the fly sweep. It is an extremely simple and effective play. Our sweeper averaged eight yards a carry on this play for us at Willamette University in the 2003 season. I take no credit for inventing this play. As far as I know, it was created by Gene Beck of Delano High School in the early 1950s. I learned it from Phil Maas and Roger Sugimoto in 1978 when I was an assistant coach at North Monterey High School in California. Over the years, I have worked at developing an offense around the sweep play. When I became a head coach, all of my background was on the defensive side of the ball. I was very aware that the sweep caused a lot of problems for a defense, and if we ran it well enough and often enough, it would force the defense to move personnel prior to the snap. When I first started coaching the sweep, I was guilty of over coaching the sweepers. Over the years, we have boiled the sweep motion down to the following six coaching points for the sweeper and quarterback. 1. Approach: This refers to where the motion back begins, and what speed he approaches the Quarterback at. There is no magic as to where to start the motion man at. We have had him start at a tight slot or be outside the numbers. We want the sweeper to aim one yard behind the Quarterback. He is running fast to the

mesh point, but he is not in a full sprint. I tell our guys, you are in fourth gear which looks fast, but once you receive the ball, you have a little more speed to use. With reps, the players develop a comfortable speed to approach the quarterback. The key coaching point is to make each approach look the same (Diagram 5). 2. Mesh: This refers to the quarterback taking the snap and turning 180 degrees so his back is to the defense and handing the ball to the sweeper. A key point is that the quarterback controls snap. Do not allow sweeper to chop steps and try and time mesh. If the timing is off, it is always the quarterbacks fault. Ideally, the quarterbacks body should hide the handoff from the defense, creating deception. I let the quarterback turn in a way that is most comfortable to him. In reality, his turn takes him 12 to 18 inches away from the center. After handing the ball to the sweeper, he will run one of his paths.

blocker on a sweep. The sweeper wants to tag the lead backs outside hip with his inside arm. As they turn up field, we want the sweeper close enough to touch the lead back. We use the analogy of being wingtip to wingtip like the jet fighters in the blue angels or thunderbird flight shows. This position puts the sweeper in perfect position as he comes around the corner. If there is no lead back, he visualizes one and catches a phantom back.

Diagram 6

Diagram 5

3. Slide step: The slide step is a critical component to being an effective sweeper. When the sweeper receives the ball or is faking, it is important that he pushes off his inside foot and moves one body width away from the LOS I have used ice skating or rollerblading as examples of the type of move it is. It is a subtle move, but it allows the sweeper to maintain speed around the corner, or make an up field cut if that is necessary (Diagram 5). 4. Ball handling & faking: As the sweeper is slide stepping, he is securing the ball as any runningback would do. If he does not receive the ball, it is important that he pumps his inside arm and holds an imaginary football in his outside arm all the way around the corner. By doing this, the fake has the potential to pull defenders to the sweeper. 5. Catch: The sweeper after slide stepping and securing the football, will try and catch the lead back. In teaching this, we put a runningback in an off set position (i.e. split back, off set I, off set in a one back set). This enables the back to be a lead

6. Set up the block: As the sweeper heads up field, we stress having a plan to make a move on defensive backs. Simply put, the sweeper attacks the defenders technique and cuts opposite of the block. If the defensive back has outside leverage, he stretches and cuts up. If he has inside leverage, sweeper attacks up field and cuts out. It is important that the sweeper works on these moves and also works on making moves on defenders in space. The speed part of the offense is supplied by the sweep play. We tell our players it is the fastest play in football. Whether it is or not, we believe it is. The deception part of the offense is supplied by the quarterbacks back being to the defense effectively hiding the ball. In addition, by mixing up paths run by a second back in a two back set, or the quarterback in a one back set, the defense will generally honor the fake. We take great pride in our faking. We stress that there are two ways to move a defender. You can physically move them, which best case is a yard or two, or you can move people by faking them, which often moves them five yards or more. I hope this article has helped you. Obviously, it is a thin slice of what we do, but it may generate some thoughts that will be of use to you and your program. It has been a privilege to write this article for the AFCA and represent Willamette University. Thank you for this opportunity and we wish you continued success this fall.

You might also like

- Triple ShootDocument5 pagesTriple Shootrbgainous2199100% (1)

- Complimentary Plays To The Outside VeerDocument6 pagesComplimentary Plays To The Outside Veercllew100% (2)

- College Football Schemes and Techniques: Offensive Field GuideFrom EverandCollege Football Schemes and Techniques: Offensive Field GuideNo ratings yet

- Effective Man To Man Offenses for the High School Coach: Winning Ways Basketball, #2From EverandEffective Man To Man Offenses for the High School Coach: Winning Ways Basketball, #2No ratings yet

- Effective Zone Offenses For The High School Coach: Winning Ways Basketball, #3From EverandEffective Zone Offenses For The High School Coach: Winning Ways Basketball, #3No ratings yet

- The Fly OffenseDocument3 pagesThe Fly OffenseMichael SchearerNo ratings yet

- Double Wing - What Plays To Run by Jack GregoryDocument6 pagesDouble Wing - What Plays To Run by Jack GregorypakettermanNo ratings yet

- Flex BoneDocument7 pagesFlex BoneJerad BixlerNo ratings yet

- 4-2-5 Vs The Flexbone - DeuceDocument11 pages4-2-5 Vs The Flexbone - DeuceTroof10No ratings yet

- 4 2 5 DefenseDocument16 pages4 2 5 DefenseMichael Schearer100% (2)

- Modern A FormationDocument29 pagesModern A FormationEdmond Eggleston Seay III100% (3)

- 63 Defense A Winning Youth DefenseDocument156 pages63 Defense A Winning Youth DefenseBrian JacksonNo ratings yet

- Fronts, Stunts, & LB Tips in The Michigan Slant 3-4 (Jim Herrman - NY Giants) (2009)Document5 pagesFronts, Stunts, & LB Tips in The Michigan Slant 3-4 (Jim Herrman - NY Giants) (2009)jeffe333No ratings yet

- Installing The 3-3-5 Defense at The High School LevelDocument109 pagesInstalling The 3-3-5 Defense at The High School LevelMichael SchearerNo ratings yet

- Fly OffenseDocument2 pagesFly Offenserbgainous2199100% (1)

- Tight 3 DefenseDocument14 pagesTight 3 DefenseMichelle Kelley Braman100% (2)

- Cover 3 Zone BlitzesDocument5 pagesCover 3 Zone Blitzescoachmark285No ratings yet

- Single Wing Playbook by Coach RolyDocument20 pagesSingle Wing Playbook by Coach RolyCoachHuffNo ratings yet

- DefenseDocument14 pagesDefenseCoachHuff100% (1)

- The Complete Installation of The Option Game - CampbellDocument348 pagesThe Complete Installation of The Option Game - CampbellBlazo Bojic100% (1)

- GMC 3-5-3 Defensive Overview 2010Document33 pagesGMC 3-5-3 Defensive Overview 2010Coach Big B100% (1)

- Flexbone Goaline PlayDocument7 pagesFlexbone Goaline PlayJerad BixlerNo ratings yet

- Umbrella Run Defense ConceptDocument7 pagesUmbrella Run Defense ConceptabilodeauNo ratings yet

- Al Groh 3-4 LB PlayDocument8 pagesAl Groh 3-4 LB PlayCoach GBNo ratings yet

- Defending The Double WingDocument20 pagesDefending The Double WingCoach BrownNo ratings yet

- 4-2-5 Run Fits Glazier11Document30 pages4-2-5 Run Fits Glazier11schaffy100% (1)

- 46 Defense Jenks HSDocument44 pages46 Defense Jenks HSCoachHuff100% (1)

- Wing-T PassingDocument9 pagesWing-T PassingScott McLaneNo ratings yet

- FlexboneDocument8 pagesFlexboneCoachKarim50% (2)

- Wing T Offense by Greg LaBelleDocument33 pagesWing T Offense by Greg LaBellewhite_mike52100% (1)

- Bruce Cobleigh 2 & 3 Scat MinnDocument51 pagesBruce Cobleigh 2 & 3 Scat Minncoachrji100% (4)

- 6-Pack Angle DefenseDocument35 pages6-Pack Angle DefenseBruce KalbNo ratings yet

- The Passing Game - Reading From High To LowDocument8 pagesThe Passing Game - Reading From High To LowCoach Brown100% (2)

- 33 Defense - Bracket Coverage & Pressure Concepts - John RiceDocument72 pages33 Defense - Bracket Coverage & Pressure Concepts - John RiceTj Hawkins100% (1)

- Mountjoy On Chow Pass ReadsDocument12 pagesMountjoy On Chow Pass ReadsCoach BrownNo ratings yet

- Neal Brown ClinicDocument4 pagesNeal Brown ClinicJerome LearmanNo ratings yet

- ILB Flow Reads and Techniques in The Run GameDocument20 pagesILB Flow Reads and Techniques in The Run GamemdfishbeinNo ratings yet

- 43 DefenseDocument19 pages43 Defensefkaram1965No ratings yet

- Rocket Toss UpdatedDocument27 pagesRocket Toss UpdatedDustin Sealey100% (4)

- Cripes! Get Back To Fundamentals... : See The Big PictureDocument13 pagesCripes! Get Back To Fundamentals... : See The Big PictureJerad BixlerNo ratings yet

- Bruce Cobleigh Waggle SolidDocument45 pagesBruce Cobleigh Waggle SolidcoachrjiNo ratings yet

- God's Play: The Modern Power Run Game: Ian Boyd@Ian - A - BoydDocument7 pagesGod's Play: The Modern Power Run Game: Ian Boyd@Ian - A - BoydJerad BixlerNo ratings yet

- Gun RunDocument10 pagesGun RunJeremiah DavisNo ratings yet

- VarsityHandoutBack PDFDocument1 pageVarsityHandoutBack PDFerickward1No ratings yet

- KY S Air Raid Offense AFCA Proceedings 1999Document3 pagesKY S Air Raid Offense AFCA Proceedings 1999Coach Brown100% (13)

- Spread OffenseDocument40 pagesSpread Offensewhite_mike52100% (1)

- 2013 Installing The I Back Offense Part 1Document30 pages2013 Installing The I Back Offense Part 1Mark Morris100% (1)

- Philosophy - Stop The Run - Don't Give Up The Cheap TD - Attacking Style Defense - Basic Zone Defense - Team Unity - Keep It Simple - Be PhysicalDocument34 pagesPhilosophy - Stop The Run - Don't Give Up The Cheap TD - Attacking Style Defense - Basic Zone Defense - Team Unity - Keep It Simple - Be PhysicalBuzzard951111100% (1)

- Touchdown: The Power and Precision of Football's Perfect PlayFrom EverandTouchdown: The Power and Precision of Football's Perfect PlayRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (4)

- The QB Mentor: Words of Wisdom From an NFL Veteran For An Injured Quarterback That Can Improve Your Life and CareerFrom EverandThe QB Mentor: Words of Wisdom From an NFL Veteran For An Injured Quarterback That Can Improve Your Life and CareerNo ratings yet

- ITF Tennis Science Review. Tennis Log Anxiety Etc - 113912Document19 pagesITF Tennis Science Review. Tennis Log Anxiety Etc - 113912germany23100% (1)

- PATHFit 3 Volleyball Tournament GuidelinesDocument4 pagesPATHFit 3 Volleyball Tournament Guidelinesherald.sottoNo ratings yet

- CEESA Athletics & Activities Calendar: HS Boys Soccer Green Bratislava October 20-23Document2 pagesCEESA Athletics & Activities Calendar: HS Boys Soccer Green Bratislava October 20-23DannyNo ratings yet

- CaptainTsubasa2 PasswordsDocument2 pagesCaptainTsubasa2 PasswordsAmril Mukmin0% (1)

- GolfDocument5 pagesGolfOwen HillNo ratings yet

- MACIPRISA Athletic Guidelines Rev. 2018-1-1Document12 pagesMACIPRISA Athletic Guidelines Rev. 2018-1-1Jerald CañeteNo ratings yet

- Beginner Water Polo ManualDocument28 pagesBeginner Water Polo Manualuntalcc100% (1)

- VOLLEYBALL POWER POINT Introduction History FacilitiesDocument23 pagesVOLLEYBALL POWER POINT Introduction History Facilitiesyuuki konnoNo ratings yet

- Basketball Is A Team Sport in WhichDocument4 pagesBasketball Is A Team Sport in Whichmohdrehan12No ratings yet

- Newfaust 1Document16 pagesNewfaust 1aditya24292No ratings yet

- 5A Qualifiers 2022Document10 pages5A Qualifiers 2022William GrundyNo ratings yet

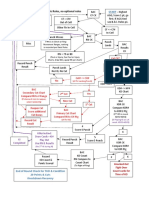

- Title Bout Flow Chart v3.0Document1 pageTitle Bout Flow Chart v3.0Chris van MelsNo ratings yet

- Progressive OverloadDocument22 pagesProgressive OverloadJayne Spencer100% (1)

- All Sheiko ProgramsDocument108 pagesAll Sheiko ProgramsMatt BarnhardtNo ratings yet

- Portfolio in Physical EducationDocument7 pagesPortfolio in Physical EducationJamaica QuetuaNo ratings yet

- Research Paper EnglishDocument7 pagesResearch Paper Englishapi-535241012No ratings yet

- Batting PDFDocument4 pagesBatting PDFapi-401963473No ratings yet

- Defensive ChecklistDocument1 pageDefensive ChecklistBen Bullock100% (1)

- Current Affairs: SportsDocument7 pagesCurrent Affairs: SportsAnkit ShuklaNo ratings yet

- PED104 Week 3 5Document14 pagesPED104 Week 3 5Loud EstoqueNo ratings yet

- Wallyball RulesDocument50 pagesWallyball RulesGuillermo CorderoNo ratings yet

- Cricket Rules PDFDocument11 pagesCricket Rules PDFapi-401963473No ratings yet

- Ball Rules: The Following Rules Will Be Used at The VNEA International ChampionshipsDocument3 pagesBall Rules: The Following Rules Will Be Used at The VNEA International ChampionshipsJewey Quimada AlberastineNo ratings yet

- Get L:?tick WLFJ Fjouth Would Do World, Get L:?e L:?le.Document8 pagesGet L:?tick WLFJ Fjouth Would Do World, Get L:?e L:?le.EveNo ratings yet

- Basketball: Physical Education 11 Activity Sheets (4 Quarter)Document4 pagesBasketball: Physical Education 11 Activity Sheets (4 Quarter)Angel DiazNo ratings yet

- Sportsfest SchedDocument8 pagesSportsfest SchedBielley DaUniMertatoNo ratings yet

- TRA Asian Champ HKG 2024 Age Group RulesDocument4 pagesTRA Asian Champ HKG 2024 Age Group Ruleszyxue0110No ratings yet

- Basketball: Basketball Is A Limited ContactDocument17 pagesBasketball: Basketball Is A Limited ContactJatin Kumar SinghaniaNo ratings yet

- SportsData PDFDocument1 pageSportsData PDFpradeepNo ratings yet

- R Canova Sondre Moen TrainingDocument4 pagesR Canova Sondre Moen TrainingDemetrio FrattarelliNo ratings yet