Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Eating Disorders, Self Esteem and Weight Dissatisfaction in Males

Uploaded by

Naim MokhtarOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Eating Disorders, Self Esteem and Weight Dissatisfaction in Males

Uploaded by

Naim MokhtarCopyright:

Available Formats

European Eating Disorders Review Eur. Eat. Disorders Rev.

6, 5872 (1998)

Paper

Eating Disturbance, Self-Esteem, Reasons for Exercising and Body Weight Dissatisfaction in Adolescent Males

Adrian Furnham* and Alison Calnan

Department of Psychology, University College London, London, UK

This study assessed body dissatisfaction, self-esteem and attitudes as well as behaviours relating to disordered eating in adolescent boys. The results indicated that males who were dissatised with their bodies are equally divided between those who wish to gain weight and those who wish to lose weight. In addition exercising for physical tone, attractiveness, health, tness and weight control were all related to measures of disordered eating, while exercising for mood, and enjoyment were not. There was no relationship between self-esteem and body weight dissatisfaction. The best predictors of satisfaction with weight were the `reasons for exercise' variables. The ndings are discussed in terms of differences between male and female body dissatisfaction and c the cultural pressure to obtain male ideal body shapes. *1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd and Eating Disorders Association.

INTRODUCTION

Much of the research on body dissatisfaction, which has focused on females, shows on the whole they are dissatised with their bodies (Cooper and Fairburn, 1983). Similar research on males has suggested that they tend to be more happy with their body weight (Leon et al., 1985), body shape (Fallon and Rozin, 1985; Huenemann et al., 1966) and physical appearance (Pliner et al., 1990). However there is increasing evidence that this is not the case. Franco et al. (1988) as well as Miller et al. (1980) have shown that many males are

*Correspondence to: Professor Adrian Furnham, Department of Psychology, University College London, 26 Bedford Way, London, WC1, UK.

CCC 10724133/98/01005815$17.50 c * 1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd and Eating Disorders Association.

European Eating Disorders Review 6(1), 5872 (1998)

Eur. Eat. Disorders Rev. 6, 5872 (1998)

Body Dissatisfaction in Adolescent Males

dissatised with their weight and shape, although somewhat less so than females. Other research has demonstrated that males are as dissatised with their body shape and weight as females (Drewnowski and Yee, 1987; Silberstein et al., 1988). The nature of body image dissatisfaction is however slightly different in males and females. Dissatisfaction with body image in females tends to always operate in the direction of weight loss while in males dissatisfaction operates in the direction of weight gain as well as weight loss. Silberstein et al. (1988) found that 4.4 per cent of the females that they studied desired to become bigger, whereas 46.8 per cent of the males desired to gain weight. In fact males seemed to be approximately equally divided into those desiring weight gain as opposed to those desiring weight loss. Drewnowski and Yee (1987) showed that 18-year-old boys were more or less evenly split into those who wished to lose and those who wished to gain body weight. Because early research did not demonstrate body dissatisfaction in males it was argued that they were not subjected to the same socio-cultural pressure to obtain an ideal shape. However, in the light of evidence suggesting that males are dissatised with their bodies it is interesting that Davis et al. (1993) have pointed out that males are increasingly being subjected to pressures to obtain the ideal culturally-prescribed shape. They point to an increasing trend for male bodies to be featured in fashion magazines and to market a variety of products. Anderson and Di Domenico (1992) conducted a survey of the articles and advertisements featured in the most popularly read male magazines and found that although the female magazines contained more diet articles, the male magazines contained more shape change articles and advertisements, and thus it would seem that males do not escape the socio-cultural pressure to achieve the ideal body shape. This difference between the desire for shape change, in males, as opposed to weight loss through dieting, in females, may be a function of the different male and female ideals, since the male ideal is a V-shaped gure while the female ideal is being extremely thin. This is also represented through the difference in perception of being underweight, since underweight males seem dissatised with their body weight, whereas underweight females appear satised (Cash et al., 1986). The desire for weight gain in males would t with the desire to gain additional muscle and to achieve the male ideal V-shaped gure rather than the addition of weight per se. The degree to which people are satised with their bodies has profound implications for their general self-perceptions, self-esteem and social behaviour. Research on the relationship between body satisfaction and self-esteem has shown that female body image satisfaction is highly correlated with selfesteem (Lerner et al., 1973). Silberstein et al. (1988) found that males' selfesteem was also affected by the degree of body dissatisfaction, regardless of the direction of the dissatisfaction.

c * 1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd and Eating Disorders Association.

59

A. Furnham and A. Calnan

Eur. Eat. Disorders Rev. 6, 5872 (1998)

Dissatisfaction with body image has another important implication since it has been suggested that it is a key risk for eating disorders (Garner and Garnkel, 1981). This link between eating disorders and body dissatisfaction has received support from a number of sources. It is often demonstrated through the high prevalence rates of eating disorders in groups where there is an increased importance in maintaining a thin ideal e.g. ballet dancers and models (Garner and Garnkel, 1980) as well as athletes (Sundgot-Borgen, 1993). Other researchers have also shown higher rates of disordered eating in male subcultures (e.g. male homosexuals) which put an increased importance on appearance (Carlot and Camargo, 1991; Silberstein et al., 1989). The link between body image and eating disorders is however not demonstrated in the prevalence rates for eating disorders in males. Rastam et al. (1989) estimate a ratio of one male to slightly more than 10 female cases of eating disorders in the general population. There is now growing evidence that prevalence rates, for males, may be somewhat an underestimate (Carlat and Camargo, 1991) since there may be a reluctance on the part of clinicians to diagnose eating disorders in males and it may also be harder to identify since there is no amenorrhoea, which is one of the diagnostic criteria for anorexia nervosa (Bliss and Branch, 1960). Also the large amount of research focusing on females and eating disorders may facilitate women's acknowledgement of the problem while discouraging males from admitting to what they would consider a female disorder. There have also been gender differences noted in the labelling of behaviour e.g. males do not label ingestion of large quantities of food as bingeing (Franco et al., 1988). The primary strategies to change shape in our current society are diet and exercise. Some researchers have suggested that it is actual dieting behaviour which represents an important factor in the development and perpetuation of eating disorders (Beaumont et al., 1976; Polivy and Herman, 1985). Excerise, on the other hand, has been thought of as merely a means of quickening weight loss or a way of denying the unpleasant effects of dieting (Bruch, 1965; Seaver and Binder, 1972). Many males want to gain weight and the male ideal in general is thought to be achieved most effectively through exercise and not solely by means of dieting. It has been suggested that because males are not engaging in dieting behaviour they are not a risk group for the development of eating disorders despite body dissatisfaction. There is now growing evidence of a link between exercise and eating disorders (Sundgot-Borgen, 1993). Kron et al. (1978) found that 21 of 33 patients diagnosed as having anorexia nervosa were highly active prior to the onset, while Katz (1986) describes two cases where an eating disorder manifested only after the individuals had become serious long distance runners and from which weight loss had logically followed consequent to the behaviour change. Katz (1986) hypothesized that this relationship between exercise and disordered eating may be due to a number of reasons including exercise creating

c * 1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd and Eating Disorders Association.

60

Eur. Eat. Disorders Rev. 6, 5872 (1998)

Body Dissatisfaction in Adolescent Males

the initial weight loss; through truly diminished appetite; increased narcissistic investment of the body or elevated production of endorphins. Other researchers have found that weight trainers and body-builders are a subpopulation at increased risk for developing eating disorders (Franco et al., 1988). Indeed body-building would be the type of exercise consistent with obtaining the male ideal body shape. Silberstein et al. (1988) suggest that the reasons why people exercise may be signicant in determining the risk for developing eating disorders. They found that exercising for weight control reasons was associated with disordered eating and that those who exercise for appearance reasons rather than health reasons may also be more at risk for the development of eating disorders. McDonald and Thompson (1992) replicated Silberstein's ndings although they used a minimum exercise criteria. They found that exercising for weight, tone and to a lesser degree for attractiveness is positively connected to eating disturbance and body-image dissatisfaction for both males and females, while exercising for tness reasons for males is negatively connected with eating disturbance. Therefore, there are strong indications that there are certain motivations for exercise that are accompanied by increases in disturbances, particularly body dissatisfaction. Alternatively there are also other motivators such as health and tness which are associated with less disturbance and greater self-esteem, especially for males. The present study focuses on adolescent pre-college males since the nature of body dissatisfaction in males is less well documented. This study is designed to replicate research on the relationship between body dissatisfaction, the reasons given for exercising, eating disturbance and self-esteem. The present study also intends to extend the previous research by Silberstein et al. (1988) and McDonald and Thompson (1992) by comparing males who wish to gain weight, lose weight and who are happy with their weight on the measures of disordered eating, self-esteem and reasons for exercise. It was hypothesized that males would be dissatised with their body weight and would be equally divided into those who wish to lose weight and those who wish to gain weight. Those males who are more dissatised with their body weight would have lower self-esteem regardless of the direction of body weight dissatisfaction. It was also hypothesized that exercising for weight control, attractiveness and tone reasons would be associated with more disordered eating while exercising for mood, health, enjoyment and tness would not be related to disordered eating.

METHOD Participants

One hundred and forty-three male participants took part in the study. Ninety of these participants were sixth form (12th grade) students attending two

c * 1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd and Eating Disorders Association.

61

A. Furnham and A. Calnan

Eur. Eat. Disorders Rev. 6, 5872 (1998)

schools in England. Both schools had predominantly middle class children and were fairly homogenous in terms of socio-economic class. The remainder were recruited from the department's subject panel. The age of the participants ranged from 16 to 18 years, the mean age being 16 years 7 months. Most were within the normal height/weight band (assessed using tables published by the British Heart Foundation, 1991), with the mean weight being 149 pounds and the mean height 69.6 inches.

Questionnaire

All participants completed a questionnaire containing the following measures: This measure is made up of eight subscales which are: drive for thinness, body dissatisfaction, bulimia, ineffectiveness, perfectionism, interpersonal distrust, interoceptive awareness and maturity fears. These measures are designed to assess a broad range of behavioural and attitudinal characteristics of eating disorders. A reliability and validity study showed substantial within-scale common variance among items and high criterion-related validity (Garner et al., 1983b). In this study all the subscales were completed by participants but only drive for thinness, body dissatisfaction, bulimia, perfectionism and maturity fears were used in the data analysis since these were of the most interest. In addition, two changes were made to the inventory. First, a number of questions were added to the body dissatisfaction scale, these questions related to areas of the body that males tend to be most dissatised with e.g. biceps, chest and shoulders. Second, an additional subscale was added which was concerned with the desire to become bigger and the wish to gain weight labelled `desire for bulk'. Participants rated themselves over a six-point scale with the most extreme `anorexic' response earning the highest score, although the additional scale was scored with the least `anoretic' response earning the highest score and therefore reected a person with an extreme desire to become bigger. This measure has seven subscales, which include exercising for the following reasons: weight control, tness, mood, health, attractiveness, enjoyment and tone. Responses to items were on a seven-point rating scale, where 1 was not at all important and 7 was extremely important. Only those participants who exercised were asked to complete this section. The inventory was developed in a sample of males and females and Silberstein et al. (1988) report alpha coefcients for all subscales above 0.67. Reliability has since been recalculated in a study comparing men only, all alpha coefcients were above 0.68 (Silberstein et al., 1989).

c * 1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd and Eating Disorders Association.

Eating disorder Inventory (Garner et al., 1983a)

Reasons for exercise (Silberstein et al., 1988)

62

Eur. Eat. Disorders Rev. 6, 5872 (1998)

Body Dissatisfaction in Adolescent Males

This is a 10-item scale, it is a widely used measure with acceptable reliability and concurrent and construct validity. Participants rated each item on a fourpoint scale (strongly agree, agree, disagree and strongly disagree). Higher scores indicated a more negative self-esteem. An information sheet was completed which included sex, age, height and parents' occupation. Also information on weight e.g. present, ideal, average for their height and age and their own highest and lowest past weight. In order to assess the number of pounds participants desired to lose or gain, a discrepancy score was calculated by subtracting ideal weight from present weight.

Background information

Self-esteem (Rosenberg, 1965)

Procedure

Participants were approached by their teachers, during school time to complete the questionnaire. Participants' parents were not approached, but the permission of the school was sought and received. They represented all of the 11th and 12th grade students in two schools. Teachers were provided with an information sheet providing details of the questionnaire measures and the aims of the study which they were asked to introduce before distributing the questionnaire. All students were given the opportunity to refuse participation but less than 1 per cent did so.

RESULTS

The sample was divided into three groups; this division was on the basis of the discrepancy score calculated i.e. present weight minus own ideal weight. Scores between 20 (desire to gain 20 pounds) and 2 (desire to gain 2 pounds) were classied as group 1 and are representative of males with an ideal larger than their present weight i.e. males who may prefer to gain weight. Scores from 1 (desire to gain 1 pound) to 1 (desire to lose 1 pound) were classied as group 2 and are representative of males with ideal and present weight which match. Scores of 2 (desire to lose 2 pounds) to 30 (desire to lose 30 pounds) were classied as group 3 and are representative of males with an ideal weight smaller than their actual weight i.e. males who may prefer to lose weight. This classication was based on the distribution observed in the sample. Table 1 reports the means and standard deviations of the overall sample and of the three individual groups. A one-way ANOV revealed only one signiA cant difference (F(2,120) 5.65, p 5 0.01) between the groups and this related to the variable of present weight, which could be considered to be a

c * 1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd and Eating Disorders Association.

63

A. Furnham and A. Calnan

Eur. Eat. Disorders Rev. 6, 5872 (1998)

Table 1. Background information variables

Variables Age Overall (N 143) Group 1 (N 47) 16.8 (SD 0.67) 147.6a (SD 19.46) 70.83 (SD 3.00) 150.9 (SD 21.33) 141.7 (SD 16.11) 153.5 (SD 16.11) 156.0 (SD 18.93) 155.7 (SD 18.93) Group 2 (N 38) 16.68 (SD 0.74) 146.5a (SD 20.9) 69.36 (SD 4.17) 150.9 (SD 22.67) 142.7 (SD 22.28) 148.5 (SD 21.44) 148.7 (SD 19.34) 146.3 (SD 20.85) Group 3 (N 38) 16.74 (SD 0.82) 160.1b (SD 19.37) 68.16 (SD 8.99) 162.3 (SD 18.84) 148.7 (SD 17.7) 152.4 (SD 15.15) 150.4 (SD 16.9) 150.2 (SD 18.43) F ratio df(2,120) 0.93 5.65* 2.24 3.37 0.94 0.83 1.88 2.52

16.76 (SD 0.74) Present weight (in 149.9 pounds) (SD 20.56) Height (in inches) 69.63 (SD 5.61) Highest past weight 153.4 (SD 21.32) Lowest past weight 142.9 (SD 20.00) Average weight for 151.5 height and age (SD 18.73) Ideal weight for your 151.9 height and age (SD 18.78) Own ideal weight 152 (SD 20.89)

Means with superscript (a, b) indicate that those with identical subscripts are not signicantly different from each other. *p 5 0.01.

reliability check. The discrepancy score was signicantly positively correlated (r 0.16, p 5 0.05) to highest past weight and signicantly negatively correlated to average (r 0.17, p 5 0.05) and ideal weight (r 0.16, p 5 0.05) for height and age. A signicant negative correlation (r 0.32, p 5 0.001) was found between the discrepancy score and own ideal. Table 2 shows the alpha reliability scores of the subscales of the Eating Disorder Inventory and self-esteem, all of which are above 0.60. Correlations between subscale scores on the Eating Disorder Inventory and the self-esteem score are also reported. The total score on the Eating Disorder Inventory was signicantly correlated to all other reported subscales apart from the drive for

Table 2. Intercorrelations of the Eating Disorder Inventory and self-esteem measures

Alpha reliability Drive for thinness Bulimia Body dissatisfaction Perfectionism Maturity fears Drive for bulk Self-esteem 0.64 0.73 0.88 0.68 0.79 0.70 0.85 Total score on EDI 0.46*** 0.32*** 0.49*** 0.36*** 0.53*** 0.11 0.41*** 0.16* 0.40*** 0.13 0.20* 0.10 0.23** 0.05 0.10 0.16* 0.20* 0.01 0.01 0.13 0.17* 0.31*** 0.22** 0.24* 0.11 Drive for thinness Bulimia Body dissatisfaction Perfectionism Maturity Fears Drive for bulk

0.02 0.15*

0.00

***p 5 0.001; **p 5 0.01; *p 5 0.05.

c * 1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd and Eating Disorders Association.

64

Eur. Eat. Disorders Rev. 6, 5872 (1998)

Body Dissatisfaction in Adolescent Males

bulk. Drive for thinness was signicantly correlated to bulimia (r 0.16, p 5 0.05), body dissatisfaction (r 0.40, p 5 0.001), maturity fears (r 0.20, p 5 0.05) and self-esteem (r 0.23, p 5 0.01). Bulimia was signicantly negatively correlated to maturity fears (r 0.16, p 5 0.05) and drive for bulk (r 0.20, p 5 0.05). Body dissatisfaction was also signicantly negatively correlated to drive for bulk (r 0.17, p 5 0.05) but positively correlated to self-esteem (r 0.31, p 5 0.001). Perfectionism was signicantly negatively correlated to drive for bulk (r 0.24, p 5 0.01) but positively correlated to maturity fears (r 0.22, p 5 0.01). Self-esteem was positively correlated with maturity fears (r 0.15, p 5 0.05). This pattern indicates that whilst some of the subscales are over lapping, others e.g. perfectionism seem to be measuring unique attitudes. Table 3 reports the intercorrelations on the Reasons for Exercise Inventory. All the subscales are highly intercorrelated indicating that the various reasons for exercising are closely related. Table 4 reports the correlations of the Eating Disorder Inventory and selfesteem score with the Reasons for Exercise Inventory. The total EDI score was signicantly correlated only to exercising for tone (r 0.20, p 5 0.05). Drive for thinness was signicantly correlated to exercising for weight control (r 0.47, p 5 0.001), tone (r 0.36, p 5 0.001), attractiveness (r 0.27,

Table 3. Intercorrelations of the Reasons for Exercise Inventory

Weight control Fitness Mood Health Attractiveness Enjoyment Tone

***p 5 0.001; *p 5 0.05.

Fitness 0.34*** 0.73*** 0.69*** 0.44*** 0.65***

Mood

Health

Attractiveness Enjoyment

0.29*** 0.29*** 0.45*** 0.33*** 0.30*** 0.52***

0.46*** 0.37*** 0.55*** 0.24***

0.52*** 0.52*** 0.49***

0.40*** 0.65***

0.21*

Table 4. Correlations of the Eating Disorder Inventory and self-esteem score with reasons for exercise

Total score on EDI Weight control Fitness Mood Health Attractiveness Enjoyment Tone 0.11 0.03 0.02 0.06 0.09 0.00 0.21* Drive for thinness 0.47*** 0.16* 0.10 0.17* 0.27** 0.03 0.36*** Bulimia 0.11 0.14 0.02 0.00 0.13 0.03 0.10 Body dissatisfaction 0.09 0.16* 0.03 0.08 0.18* 0.01 0.41*** Perfectionism 0.17* 0.18* 0.01 0.03 0.17* 0.05 0.21* Maturity fears 0.00 0.03 0.15 0.13 0.03 0.05 0.07 Drive for bulk 0.12 0.36*** 0.00 0.18* 0.28** 0.10 0.33*** Selfesteem 0.07 0.05 0.10 0.00 0.03 0.04 0.17

***p 5 0.001; **p 5 0.01; *p 5 0.05.

c * 1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd and Eating Disorders Association.

65

A. Furnham and A. Calnan

Eur. Eat. Disorders Rev. 6, 5872 (1998)

p 5 0.01), tness (r 0.16, p 5 0.05) and health (r 0.17, p 5 0.05). Body dissatisfaction was signicantly correlated to exercising for tness (r 0.16, p 5 0.05) and exercising for tone (r 0.41, p 5 0.001). Perfectionism was signicantly correlated with exercising for weight control (r 0.17, p 5 0.05), tness (r 0.18, p 5 0.05), attractiveness (r 0.17, p 5 0.05) and tone (r 0.21, p 5 0.05). Drive for bulk was signicantly negatively correlated to exercising for tness (r 0.36, p 5 0.001), tone (r 0.33, p 5 0.001), attractiveness (r 0.28, p 5 0.01) and health (r 0.18, p 5 0.05). Bulimia, maturity fears and self-esteem were not signicantly correlated to any of the reasons for exercise. Overall these results tend to support the second hypothesis namely that eating disorders are signicantly associated with reasons for exercise. The next stage of the analyses was completed using group scores, as opposed to overall scores. Table 5 shows the means and standard deviations for the three groups relating to self-esteem, Eating Disorder Inventory and to reasons for exercise. A one-way ANOV revealed signicant differences between the A three groups on body dissatisfaction (F(2,118) 4.58, p 5 0.05), drive for bulk (F(2,113) 6.07, p 5 0.01) and on exercising for weight control (F(2,100) 6.37, p 5 0.01). Finally, to examine which was the best predictor for the discrepancy score a stepwise multiple regression was carried out using all the variables. The ve best signicant predictor variables were health (beta 0.80, (p 5 0.001), tone (beta 0.40, p 5 0.01), bulimia (beta 0.32, p 5 0.01), maturity fears (beta 0.29, p 5 0.05), and height (beta 0.31, p 5 0.05), and together they accounted for 80 per cent of the variance. Thus the single factor of health being the reason for exercise was the single best predictor of the discrepancy score.

DISCUSSION

As predicted males, like females, were found to be generally dissatised with their bodies with 69 per cent of the participants reporting that their present weight was different to their ideal. Those males reporting dissatisfaction with their body weight were approximately divided into those who wanted to lose weight (31 per cent) and those who wanted to gain weight (38 per cent). These gures report a similar trend to that found in previous research (Drewnowski and Yee, 1987) and reconrm the hypothesis that body dissatisfaction is not a characteristic unique to females. These gures also demonstrate that the nature of male body dissatisfaction is slightly different to that of females in that some males express dissatisfaction when they perceive themselves as being underweight whereas females tend to be happier (Cash et al., 1986). The wish to gain weight by males would be associated with the desire to become more muscular and achieve the male ideal of a V-shaped gure. It is

c * 1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd and Eating Disorders Association.

66

Eur. Eat. Disorders Rev. 6, 5872 (1998)

Body Dissatisfaction in Adolescent Males

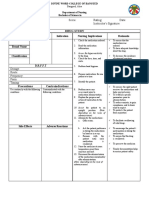

Table 5. Means and standard deviations of Eating Disorder Inventory, self-esteem and reasons

Group 1 (gain weight) (N 47) Mean (SD) 18.45 (SD 4.66) 28.00 (SD 11.33) 0.85 (SD 1.28) 2.07 (SD 3.17) 4.00ab (SD 4.5) 4.90 (SD 3.83) 4.60 (SD 3.3) 2.86a (SD 3.41) 7.83a (SD 3.52) 19.84 (SD 4.42) 11.24 (SD 4.91) 12.83 (SD 4.53) 11.79 (SD 4.06) 18.23 (SD 5.48) 15.21 (SD 4.08) Group 2 (matchedweight) (N 38) Mean (SD) 17.97 (SD 5.05) 20.00 (SD 1.99) 0.66 (SD 1.4) 1.76 (SD 3.20) 2.18a (SD 2.49) 4.40 (SD 3.72) 4.20 (SD 3.5) 0.97b (SD 1.68) 8.55b (SD 4.01) 18.07 (SD 6.94) 10.23 (SD 5.24) 10.93 (SD 5.55) 10.80 (SD 4.18) 18.07 (SD 5.58) 13.90 (SD 4.82) Group 3 (lose weight) (N 38) Mean (SD) 18.73 (SD 5.52) 27.14 (SD 15.88) 1.64 (SD 2.02) 1.26 (SD 2.11) 5.64b (SD 7.00) 5.13 (SD 4.11) 5.06 (SD 4.5) 1.06b (SD 1.76) 11.10b (SD 4.33) 18.59 (SD 4.83) 12.20 (SD 5.22) 12.97 (SD 4.52) 12.60 (SD 3.50) 18.53 (SD 5.92) 14.50 (SD 4.03)

Variables Self-esteem Total EDI Drive for thinness Bulimia Body dissatisfaction Perfectionism Maturity fears Drive for bulk Reasons for exercise Weight control Fitness Tone Attractiveness Mood Health Enjoyment

F-ratio (df 2,120) 0.23 3.61 2.61 0.80 4.58* 0.33 0.48 6.67** 6.37** 1.07 1.14 1.72 1.43 0.05 0.83

Means with identical subscript (a, b) are not signicantly different from each other. **p 5 0.01; *p 5 0.05.

unlikely that this is a symptom of disturbed behaviour, though in some instances it could be. The ndings of McDonald and Thompson (1992) regarding reasons for exercise were partially replicated since exercising for attractiveness, weight control and tone were found to be positively correlated with drive for thinness, while exercising for tone was also correlated with more body dissatisfaction. Exercising for mood, and enjoyment were not found to be correlated with

c * 1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd and Eating Disorders Association.

67

A. Furnham and A. Calnan

Eur. Eat. Disorders Rev. 6, 5872 (1998)

increased eating disturbance or self-esteem; although only exercising for tone was found to be related to an overall increase in eating disturbance demonstrated through higher total scores on the Eating Disorder Inventory. The current ndings did not replicate McDonald and Thompson (1992) in that exercising for weight control was not associated with bulimia, nor was exercising for attractiveness associated with lower self-esteem. Moreover, exercising for both tness and health reasons were found to be correlated with increased, rather than decreased, eating disturbance in that both were correlated with drive for thinness while tness was also correlated with increased body dissatisfaction, yet neither were related to increased positive self-esteem. These differences were perhaps due to differences in the participants, since McDonald and Thompson (1992) used American male college students with a mean age of 23.01 years who all met a minimum exercise requirement of 60 min of exercise per week (at least 3 days/week and 20 min/day), while the present study used English male sixth form students with a mean age of 16 years 7 months and there was no minimum exercise requirement although participants who did not exercise were not required to complete the reasons for exercise part of the questionnaire. The present study included additional Eating Disorder Inventory subscales: maturity fears, perfectionism and drive for bulk which were not used by McDonald and Thompson (1992). Maturity fears was not found to be related to any of the reasons for exercising, while exercising for tness, attractiveness, tone and weight control were all found to be positively correlated to perfectionism. Exercising for tness, attractiveness, tone and health were all negatively correlated to drive for bulk since all these reasons were positively correlated to drive for thinness. This does however suggest that the reasons offered are not the ones that people with a desire to gain weight would necessarily offer. There do appear to be motivators for exercise which are not related to an increase in eating disturbance such as mood control and enjoyment, while other reasons for exercise are positively correlated to an increase in eating disturbance e.g. tone, attractiveness, weight control, health and tness. The present study aimed to extend research by comparing those males who wish to gain weight, lose weight and who were happy with their weight. Results showed that exercising for mood reasons was not related to increased eating disturbance in any of the three groups; in fact exercising for mood was negatively correlated to drive for thinness for the weight gain group. This suggests that males who wish to gain weight and exercise for mood reasons will have lower levels of eating disturbance. This result suggests that the simple concept of weight dissatisfaction, at least in males, is a poor question because it needs to differentiate between two distinct groups: those wishing to gain and those wishing to lose weight. Exercising for enjoyment, for the gain weight group, was also related to lower scores on the body dissatisfaction and perfectionism scales. However, the Eating

c * 1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd and Eating Disorders Association.

68

Eur. Eat. Disorders Rev. 6, 5872 (1998)

Body Dissatisfaction in Adolescent Males

Disorder Inventory is perhaps not the best measure to examine the correlates of a desire to gain weight since it is designed to measure the attitudes and behaviours of people suffering from eating disorders relating to the pursuit of thinness. There is therefore no reason to expect that those people who desire to become bigger should score highly on this measure and therefore the reasons for exercise for group 1 would be negatively correlated with eating disturbance. Although in the present study two additions were made to the Eating Disorder Inventory, rst to try and take into account previous research which demonstrated that males are dissatised with different areas of their body, questions were added to the body dissatisfaction scale. Indeed body dissatisfaction was found to be correlated with exercising for tone for the gain weight group. The new subscale (drive for bulk) was included which attempted to specically examine those males with an extreme desire to gain weight. This subscale was not found to be correlated to the total Eating Disorder Inventory score, unlike the other subscales, this appeared to be measuring a unique set of behaviours. Although it was correlated with body dissatisfaction, perfectionism and bulimia these factors are important both in the desire for thinness and the desire for weight gain. The drive for bulk scale, for the weight gain group, was correlated with exercising for tness (which measured reasons for exercising relating to the improvement of muscle tone, strength and stamina), attractiveness (which measured reasons relating to improvement in attractiveness and to become desirable to the opposite sex) and tone (which related to improvement in overall body shape and specic areas). Exercising for tness and tone could be interpreted in terms of the desire for the male ideal Vshaped body in that both could contribute to the acquisition of upper body strength which in turn contributes to the male ideal. Previous research has found that attractiveness is a key dimension in body satisfaction for males (Silberstein et al., 1988). In summary the only reason for exercise which is not related to disordered eating for all three groups is mood, while exercising for tone and attractiveness are all related to disordered eating for all three groups. The present study did not replicate Silberstein et al.'s (1988) nding that the self-esteem of those males who are happy with their body weight is signicantly higher than the self-esteem of those males who are dissatised with their weight. Like Silberstein et al. (1988) there was no difference in the selfesteem of males who want to be bigger compared to those who want to be smaller. Silberstein et al. (1988) did however nd that there was no relationship between female body dissatisfaction and self-esteem, this was hypothesized to be due to a mechanism described as normative discontent. This occurs when a society places increased emphasis on appearance and ideals, resulting in more people feeling body dissatisfaction. However this has a paradoxical effect since body dissatisfaction is then felt as culturally normative and has less impact on self-esteem. The lack of relationship between self-esteem and body dissatisfaction, found in this study for males, suggests that males are being

c * 1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd and Eating Disorders Association.

69

A. Furnham and A. Calnan

Eur. Eat. Disorders Rev. 6, 5872 (1998)

increasingly exposed to cultural pressures to realize societal ideals (Davis et al., 1993) resulting in body dissatisfaction being the norm. Self-esteem was, however, correlated with the total score on the Eating Disorder Inventory and to three of its subscales: drive for thinness, body dissatisfaction and maturity fears. Self-esteem was not related to any of the reasons for exercise however when considering the whole sample. When examining the three groups separately self-esteem was found to be correlated to body dissatisfaction for the two `malcontent' groups. Therefore it appears that self-esteem is not correlated to weight dissatisfaction but it is correlated, for all three groups, with attitudes and behaviours relating to disordered eating. Self-esteem was not correlated with any of the `reasons for exercise' for either `malcontent' group but it was correlated with exercising for tone for `content' group. Self-esteem was therefore related to only one reason for exercisetone, for the one group with no weight dissatisfaction. Self-esteem may therefore primarily be related to disordered eating rather than weight dissatisfaction. The difference between present and ideal weight i.e. the discrepancy score according to which the groups were divided was found to be correlated to four of the background variables, including highest past weight which suggests that those with higher past weights were more likely to perceive themselves as overweight. Crisp and Toms (1972) have noted that the development of eating disorders in males is often associated with a background of being overweight. The discrepancy score was also negatively correlated with perceived average and ideal weight for height and age and own ideal, which implies that those males who perceive these variables to be higher perceived themselves as being underweight. However although the discrepancy score was correlated with these factors there was no actual difference in the perception of average and ideal weights between the three groups. A multiple regression showed that ve variables could account for 80 per cent of the variance of the discrepancy score. These variables were height plus two reasons for exercising: health and tone, and two attitudes and behaviours relating to disordered eating: bulimia and maturity fears. Interestingly none of the weight variables were signicant predictors of the discrepancy score and therefore of weight dissatisfaction, which suggests that weight dissatisfaction cannot be predicted from present weight and is therefore not necessarily a function of actually being over- or underweight. Also, weight dissatisfaction is not predicted by perceptions of ideal or average weights which suggests that it is not a function of having an extreme ideal. Self-esteem was also not predictive of weight dissatisfaction which supports the earlier correlational ndings which suggest that self-esteem is related to disordered eating rather than weight dissatisfaction. Finally it is suggested that future research requires more attention to be paid to the population of males who wish to gain weight. Since the majority of previous research on body dissatisfaction in relation to eating disorders has

c * 1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd and Eating Disorders Association.

70

Eur. Eat. Disorders Rev. 6, 5872 (1998)

Body Dissatisfaction in Adolescent Males

concentrated on women the measures used have concentrated on the desire to lose weight. With evidence, however, that men are not satised with their bodies and that this body image dissatisfaction also operates in the direction of weight gain more research is required to concentrate on the issue of the desire to gain weight and the association with psychological disturbance which requires the development of new measures. More importantly, these ndings suggest there may be important sex differences in the aetiology of eating disorders, though small numbers of males make research difcult in this area.

REFERENCES

ANDERSON, A. E. and Di Domenico, L. (1992). Diet vs. shape content of popular male and female magazines: A dose response relationship to the incidence of eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 11, 283287. BEAUMONT, P. J., George, G. C. and Smart, D. E. (1976). `Dieters' and `vomiters and purgers' in anorexia nervosa. Psychological Medicine, 6, 617622. BLISS, E. L. and Branch, C. H. H. (1960). Anorexia Nervosa. New York: Hoeber. BRITISH HEART FOUNDATION (1991). Food and your heart. Heart information series, no. 7. BRUCH, H. (1965). The psychiatric differential diagnosis of anorexia nervosa. In: Anorexia Nervosa: Symposium 24/25th April in Gotting (eds J. E. Meyer and H. Feldmann). Stuttgart: Thiemme, pp. 7087. CARLOT, D. and Camargo, C. (1991). Review of bulimia nervosa in males. American Journal of Psychiatry, 148, 831843. CASH, T. F., Winstead, B. A. and Janda, L. H. (1986). The great American shape-up. Psychology Today, 3037. COOPER, P. J. and Fairburn, C. G. (1983). Binge-eating and self induced vomiting in the community: A preliminary study. British Journal of Psychiatry, 142, 139144. CRISP, A. and Toms, D. A. (1972). Primary anorexia nervosa or weight phobia in the male: Report on the teen cases. British Medical Journal, 1, 334338. DA VIS, C., Shapiro, M. C., Elliot, S. and Dionne, M. (1993). Personality and other correlates of dietary restraint: An age by sex comparison. Personality and Individual Differences, 14, 297305. DREWNOWSKI, A. and Yee, D. K. (1987). Men and body image: Are males satised with their body weight? Psychosomatic Medicine, 49, 626634. FALLON, A. E. and Rozin, P. (1985). Sex differences in perceptions of body shape. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 94, 102105. FRANCO, S. N., Tamburrino, M. B., Carroll, B. T. and Bernal, G. A. A. (1988). Eating attitudes in college males. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 7, 285288. GARNER, D. M. and Garnkel, P. E. (1980). Socio-cultural factors in the development of anorexia nervosa. Psychological Medicine, 10, 647656. GARNER, D. M. and Garnkel, P. E. (1981). Body image in anorexia nervosa: Measurement theory and clinical implications. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 11, 263284.

c * 1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd and Eating Disorders Association.

71

A. Furnham and A. Calnan

Eur. Eat. Disorders Rev. 6, 5872 (1998)

GARNER, D. M., Olmstead, M. P. and Polivy, J. (1983a). The eating disorder inventory: A measure of cognitive-behavioural dimensions of anorexia nervosa and bulimia. In: Anorexia Nervosa: Recent Developments in Research (ed. A. Liss). New York: LEA. GARNER, D. M., Olmstead, M. P. and Polivy, J. (1983b). Development and validation of a multidimensional eating disorder inventory for anorexia nervosa and bulimia. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 2, 1534. HUENEMANN, R. L., Shapiro, L. R., Hampton, M. D. and Mitchell, B. W. (1966). A longitudinal study of gross body composition and body conformation and their association with food and activity in a teen-age population. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 18, 325338. KATZ, J. L. (1986). Long-distance running, anorexia nervosa, and bulimia: A report of two cases. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 27, 7478. KRON, L., Katz, J. L. and Gorzynski, G. (1978). Hyperactivity in anorexia nervosa: A fundamental clinical feature. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 19, 433439. LEON, G. R., Carroll, K., Chernyk, B. and Finn, B. (1985). Binge eating and associated habit patterns within college students and identied bulimic populations. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 4, 4357. LERNER, R. M., Karabenick, S. A. and Stuart, J. L. (1973). Relations among physical attractiveness, body attitudes and self concept in male and female college students. Journal of Psychology, 7, 219231. MILLER, T. M., Coffman, J. G. and Linke, R. A. (1980). Survey on body image, weight and diet of college students. Journal of American Dietic Association, 77, 844846. McDONALD, K. and Thompson, J. K. (1992). Eating disturbance, body image dissatisfaction, and reasons for exercising: Gender differences and correlational ndings. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 11, 289292. PLINER, P., Chaiken, S. and Flett, G. (1990). Gender differences in concern with body weight and physical appearance over the life span. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 16, 263273. POLIVY, J. and Herman, C. P. (1985). Dieting and bingeing: A causal analysis. American Psychologist, 40, 193201. RASTAM, M., Gillberg, C. and Garton, M. (1989). Anorexia nervosa in a Swedish urban region: A population based study. British Journal of Psychiatry, 155, 642646. ROSENBERG, M. (1965). Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. SEA VER, R. L. and Binder, H. J. (1972). Anorexia nervosa and other anorectic states in man. Advances in Psychosomatic Medicine, 7, 257276. SILBERSTEIN, L. R., Mishkind, M. E., Striegal-Moore, R. H., Timko, C. and Rodin, J. (1989). Men and their bodies: A comparison of homosexual and heterosexual men. Psychosomatic Medicine, 51, 337346. SILBERSTEIN, L. R., Striegal-Moore, R. H., Timko, C. and Rodin, J. (1988). Behavioural and psychological implications of body dissatisfaction: Do men and women differ? Sex Roles, 19, 219232. SUNDGOT-BORGEN, J. (1993). Prevalence of eating disorders in elite female athletes. International Journal of Sport Nutrition, 3, 2940.

c * 1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd and Eating Disorders Association.

72

You might also like

- Tom Behan Dario Fo Revolutionary Theatre 2000Document176 pagesTom Behan Dario Fo Revolutionary Theatre 2000Naim MokhtarNo ratings yet

- Beagle Hash BlueDocument1 pageBeagle Hash BlueNaim MokhtarNo ratings yet

- Geography Past PaperDocument56 pagesGeography Past PaperNaim Mokhtar81% (27)

- NOTES FOR TEACHERS ON THE SET POEMS For examination in June and November (Years 2013, 2014, 2015) SONGS OF OURSELVES: THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE INTERNATIONAL EXAMINATIONS ANTHOLOGY OF POETRY IN ENGLISH IGCSE SYLLABUS 0486 IGCSE SYLLABUS 0476 O LEVEL SYLLABUS 2010Document29 pagesNOTES FOR TEACHERS ON THE SET POEMS For examination in June and November (Years 2013, 2014, 2015) SONGS OF OURSELVES: THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE INTERNATIONAL EXAMINATIONS ANTHOLOGY OF POETRY IN ENGLISH IGCSE SYLLABUS 0486 IGCSE SYLLABUS 0476 O LEVEL SYLLABUS 2010Naim Mokhtar100% (2)

- How It Works - Step-by-Step GuideDocument1 pageHow It Works - Step-by-Step GuideNaim MokhtarNo ratings yet

- CIE Lang Summer 2012 1Document8 pagesCIE Lang Summer 2012 1Naim MokhtarNo ratings yet

- Around Existing Urban Areas If The Government Does Not Act Soon. Nearby Commuter Towns Such AsDocument2 pagesAround Existing Urban Areas If The Government Does Not Act Soon. Nearby Commuter Towns Such AsNaim MokhtarNo ratings yet

- Chemistry Specification Copy-2Document60 pagesChemistry Specification Copy-2Naim MokhtarNo ratings yet

- Google's history and servicesDocument1 pageGoogle's history and servicesNaim MokhtarNo ratings yet

- Google's history and servicesDocument1 pageGoogle's history and servicesNaim MokhtarNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5783)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Jurnal Herpes PDFDocument9 pagesJurnal Herpes PDFIstianah EsNo ratings yet

- Clinical Tips in Cardiovascular EmergenciesDocument86 pagesClinical Tips in Cardiovascular EmergenciesAbdul Quyyum100% (3)

- Health Management For Fattening PigsDocument24 pagesHealth Management For Fattening PigsMarwin NavarreteNo ratings yet

- 5744cb41-031d-4226-9cea-07098cf4c210Document28 pages5744cb41-031d-4226-9cea-07098cf4c210wahyuna lidwina samosirNo ratings yet

- First Responder Grant Waiver LetterDocument2 pagesFirst Responder Grant Waiver LetterepraetorianNo ratings yet

- Managing dental patients with cardiovascular diseasesDocument54 pagesManaging dental patients with cardiovascular diseasesSafiraMaulidaNo ratings yet

- Thesis Topics For MD Obstetrics and GynaecologyDocument8 pagesThesis Topics For MD Obstetrics and Gynaecologyelizabethjenkinsmilwaukee100% (2)

- All Health Promotion Questions 2023Document18 pagesAll Health Promotion Questions 2023Top MusicNo ratings yet

- Nutraceuticals: A New Paradigm of Pro Active Medicine.: Antonello SantiniDocument58 pagesNutraceuticals: A New Paradigm of Pro Active Medicine.: Antonello SantiniWadud MohammadNo ratings yet

- Scar Endometriosis Case Report With Literature ReviewDocument3 pagesScar Endometriosis Case Report With Literature ReviewelsaNo ratings yet

- Detailed Lesson Plan in HealthDocument5 pagesDetailed Lesson Plan in HealthRizrald Amolino91% (22)

- Factors Associated with ADHD Medication Prescription RatesDocument9 pagesFactors Associated with ADHD Medication Prescription RatesNancy Dalla DarsonoNo ratings yet

- INTAN SARI - Fix JOURNAL READING KULITDocument13 pagesINTAN SARI - Fix JOURNAL READING KULITIntanNo ratings yet

- Advanced To Consultant Level FrameworkDocument22 pagesAdvanced To Consultant Level FrameworkRuxandra InteNo ratings yet

- 74 Poy Casestudy 11 1 PDFDocument8 pages74 Poy Casestudy 11 1 PDFDani AzcuetaNo ratings yet

- Neo Int 9 November 2021Document35 pagesNeo Int 9 November 2021Prima Hari NastitiNo ratings yet

- Tricking Kids Into The Perfect ExamDocument2 pagesTricking Kids Into The Perfect ExamLesterNo ratings yet

- Workshop Risk AssesmentDocument1 pageWorkshop Risk Assesmentapi-316012376No ratings yet

- Steps Plus VI Test U7 A 2Document3 pagesSteps Plus VI Test U7 A 2KrytixNo ratings yet

- 15-17 - 7-PDF - Community Medicine With Recent Advances - 3 PDFDocument3 pages15-17 - 7-PDF - Community Medicine With Recent Advances - 3 PDFdwimahesaputraNo ratings yet

- Health Benefits of Spices - Kisan WorldDocument4 pagesHealth Benefits of Spices - Kisan WorldSomak MaitraNo ratings yet

- Types of Skin Cancer ExplainedDocument1 pageTypes of Skin Cancer ExplainedGalo IngaNo ratings yet

- Risk Assessment - AbbDocument3 pagesRisk Assessment - AbbAbdul RaheemNo ratings yet

- Home Visitation FormDocument1 pageHome Visitation FormLovella Lazo71% (7)

- Assessing Childbearing WomenDocument24 pagesAssessing Childbearing WomenCrestyl Faye R. CagatanNo ratings yet

- Cardio Notes 2Document11 pagesCardio Notes 2AngieNo ratings yet

- Osteoarthritis & Rheumatoid ArthritisDocument60 pagesOsteoarthritis & Rheumatoid ArthritisSaya MenangNo ratings yet

- Hazardous Waste Case - Lead Poisoning in Mona Commons, Jamaica PDFDocument10 pagesHazardous Waste Case - Lead Poisoning in Mona Commons, Jamaica PDFOPGJrNo ratings yet

- Mo Spec NJ 156Document17 pagesMo Spec NJ 156mohit kambojNo ratings yet

- Drug Study NCP Template 2Document2 pagesDrug Study NCP Template 2Janico Lanz BernalNo ratings yet