Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Social Inequalities in Health CH 4

Uploaded by

Prabir Kumar ChatterjeeOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Social Inequalities in Health CH 4

Uploaded by

Prabir Kumar ChatterjeeCopyright:

Available Formats

Health Inequity and Democratic Deficit

A Viewfrom East and NorthFast India

THE TEAM

Toa BRccnr Murnr.Esun RaHauaN G,q,n MaNanr Maluuoan S,,NcRAN4 Muxnenlne Pxrya.Nxa NaNoy KuunnRaNa Pra SpN

ADDITIONAL

ACADEMIC SUPPORT

SusurraBaNrn;ee.tNo M.a.NasEss Sanxan

LOGISTICAL SUPPORT Sauux MuxHERlee, SuuaNraPar aNo Suln Aosrc,q.nr

and Economic 4. Social in Ineq lities Health ua

'lMhat In the Mahabharata\,Dharma disguised as a yaksha asksKing Yudhisthira: is the greatest achievement of humanity?" The King answered decisively, "Recovery from ill heaith". The Mahabharatais not the only ancient text to have emphasised the role of health and healthcare in human development. Nevertheless, it is only recently that the concern for health has taken a "public" line, departing from its eadier, privileged-class exclusivity. And, with growing discourse on democracy and clarity surrounding the concept of development, the discussion and actions on public health have tended to follow a line that takes into account the social and economic diversitiesof a gtven region, and their implications on health. In Amartya Sen'sanalysis,rzrl,rng health status among different sections of the population is caused by their varying social and economic conditions. V/hile "women emerge as s1'stematicallyunderprivileged vis-a-vis men", this discrimination is further The WHO Commisssion on Social extended to different castes and classes.2 Determinants of Health observes: The poor health of the poor, the socialgradient in health within countries, and the marked health inequrties betrveen countries are caused by the unequal distribution of power, income, goods and services,globally and nationally,the consequentunfairnessin the immediate, visible circumstances of peoples' lives - their accessto health care, schools and communities, towns or cities - and their chances of leading a flourishing life. This unequal distribution of health-damagingexperiencesis not in any sense "natt)ral" phenomenon, but is the result of a toxic combination of poor social policies and progtammes, unfait economic arrangements,and bad polincs.3 India being a countrv with wide social and economic spectrum, regional and

A VrturlnoraI

several other diversities has perhaps become more acutely subiected to the implications of the "toxic combination of poor social poJiciesand programmes, unfair economic arrangements,and bad politics." It is perhaps uninformed politics that lead to poor financial allocation on health. But, at the same time, we must recognise that it is poor social policies and consequent implementational failure that add to an uneven delivery of public health services,where the medicalised view of health, with a high class-bias,reigns supreme. This results in an uneven development of the health facilities grving way to a burgeoning private sector. For example, according to recent statistics the number of hospitals grew from 1.1.,174 hospitals in 1991 to18,218 in 2003. But in this growth the public sector has gone down from 43 percent to 25 percent.aAgain, in 2000, the country had 1.25 million doctors, but the ratio of doctors to population in rural areas is almost six times lower than that in the urban population.s Again, the ratio of hospital beds to population in rural areas is fifteen times lower than that for urban areas.6Per capita expenditure on public health is seven times lower in rural areas, compared to government health spending for urban areas. Only 'l.7oh of all health expenditure in the country is borne by the state, and 820/o comes as'out of pocket payments'by the people. This makes the Indian public health system grossly inadequate and under-funded. Only five other countries in the wodd are worse off than India regarding public health spending @urundi, Myanmar, Pakistan, Sudan, and Cambodia;.7 This resulrs in poor health achievement, which we vrill discuss presently focusing upon some indicators. rNEeuAllr/ SunvrvRL Let us begin first by undedining survival inequality. In a country where more than 50 children per thousand do not even see their first birthday, any public policy on health cannot but take serious note of this in order to improve the chances of survival of the children. And, while doing this one has to address the issues of social and economic variations. From the NFHS III data we can see the wide differences in infant mortahqr rate between various social and economic categories.There are, however, significant inter-regional variations in this respect even among the same social categories.This has perhaps resulted due to variations in the existing public policies regarding health. SRS data are avallable for more recent years, but for the purpose of comparison between various social categories we have used NFHS data here, as SRS do not give us the disaggregated figures. It is quite clear that the more disadvantaged or lower a group's social position, the worse the average health status of its members.

jL+

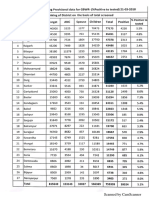

D:lttir rnn lrurQutrv DrivtlcRLttr: Hrp.rru social *t:*" Rate among different Table 4.1 Infant Mortaliry @

",'::

States and IMR in Selected of Agricultural Labourers ProPortion

90 80 70 60 50

Q

't ASM

* jKD TPRT * IND

j*

MEG * MNP

\{ts

30 20 10 0

Agricultural Labourer Soutce: Census 2001

* A Vrrv.r r.ncr,,r ann Nr Elsr According to the data presented in the Table 4.1the infant mortality r te differs across different economic classes:children in the lowest wealth quintile are more than twice as likely to die before completing oneyear as the children in the highest wealth quintile. Importandy, there are regional variations in degrees of economic disadvantage, caused to a Iarge extent by the differential in state attention on health. According to NFHS III data, in orissa IMR is the highest in the lowest income group (79.8) and is the lowest among the highest income group Q8). Let us take another example. The overall performance of \fest Bengal in reducing IMR looks promising, but with a substantial gap of 7,38 points between rural and urban areas in this respect, indicating poor policy focus on health in the rural areas, inhabited largely by the poor and socially disadvantaged groups. There is a strong indication that residing in rural India, belonging to a Scheduled caste or a scheduled Tribe, and having a low economic stature have become predictors of ill-health and health inequity in our country.e From an analysis of the IMR10 and census data for the select states we find a very strong correlation between the proportion of agricultural labourer in the workforce and IMR. The correlation coefficient, (* 0.51), implies that with higher proportion of agricultural labourers in the workforce, the IMR also shoots up. Figure 4.1.,cleaiy lllustrates that the proportion of IMR has been considerably higher among the agicultural labourers - who according to census data arc more likely to belong to SC, ST or other backward classesand religious minorities. Also, a strong correlation between Female Literacy Rate (FLR) and IMR was found - the correlation coefficient of O0.61 is indicative of the strong negative association of rvomen's access to primary level education and the mortality of their children.

90 80 70 60 *50

a

+

JKD

? BHR 1 O axro oR

+ ,ASi\I *TPR l} WB NLD

t rND

*nmc

40 30 20 10

* SIK 0' 0 . 10 20 30 40 50 Femaleliteracy

* MNP

* MIZ

60

70

80 90 10i Source: Census 2001

JO

A n E A L T I - il l ' , J F Q U l l Y N U l . l L M U L T { A l r Ll r i t l L i l

lNreuRrtw NurRrrroruar

The story does not end here. Children who survive face gross nutritional discrimination leading to poof health of the population. Undernutrition has been a maior concern in India and its inflated level is ^ m ttef of serious woffy' Forty two pef cent of children under five yeats of age are underweight which indicates their being denied of basic nutritional requirements in the very first In years of their life.11 \WestBengal thirty nine pef cent are underweight suggesting chronic and acute malnutrition.

and Economic Classes Table 4.2 Nutritional Inequality among Children in Different Social Groups

in Again, the regional contfasts in undernutriotion are glaring: it is acute N{eghalaya Bihar (55.9 per cent) and Jharkhand (56'5 per cent)' followed by (19'9 per cent)' Sikkim (48.8 per cent), while the rate is much lower in Mizotam (19.7 per cent) and Manipur Q2.I per cent)' Once again we find a connecflon A decrease between the nutritionai level and the wealth index of the households. of underweight in family income appears to contribute to a higher Percentage more children. It revealsthat children belonging to Pooref famiuesexperience difference nutrirional deprivation than the relativelyweil off ones.The nutritional in \west Bengal (17.5 percentage between the rich and the poor is the highest points). From Let us focus more closely on the nutritional condition in West Bengal' 2009),it has been found that in the IGDS monthly pfogfess fepofts (December

A Vrrw tnor.,l E;rsr aNDNcrlH Ensrlllnrn

37

West Bengal 63 per ceqt of children comes under the normal grade and 33 per cent of children comes under grade I and grade II level which is moderately underweight and four per cent of children are in the grade III and grade IV level which is severelyunderweight. But, the district-vzisevariations in nutritional deficiency are wide: the proportion of children in the normal grade is comparafively higher in Darjeeling and North 24 parganas (75 per cent) and the percentage of children in the grade III and grade IV level rs the highest in Paschim Medinipur(l3 per cent).12The nutritional problem is comparatively lower among the Hindus than among the Muslims. In \west Bengal the difference between the Muslims and the Hindus in this regard is of 2.6 percenragepoints (Hindu - 40.3, Muslim - 37.7),while in Tripura it is in the order of 17 percentage points (Hindus - 36.5 and Muslims - 53.5).As regards social identity. the nutritional deficiency is higher among the Scheduled tribes followed by the Scheduled castes. In \il/estBengal the underweight children among SCs,STs and oBCs are 40, (r0 and 23 per cent respectively. ButJharkhand has performed very poorly rn this respectwherc under-wcight children among SCs,STs,and OBCs are77,79 and 67 per cent respectivel)r. Pni rrlLt wcL o f: ANl/\[fv1 Ati] I'i i t 5or-to- ti,r.truotvi D lvtDt: ll\ l) tc Anaemia is a very common ailment in india, a direct result of nutritir>nal cleficiencies.Anaemia has a detrimental effect on the health of women and Table 4.3 Prevalence of Anaemia among children from different social groups and economic classes

: : As*xtn Anin*chtiPradb-sh

69.6 56,g. 41.1, 64.4 442 NA 59.2 ' 62;9

l'9I .

78 70i ,

6t;

69,5"'

38

Dtrtcit r.nn Hrnru ltrrQutn Drl'tocRpltc pennatal children, and may become an undedying causeof maternal moftality and birth mortality. It also results in an increased risk of premature delivery and low children because it can weight of children. It is a serious problem for young ,.rJt in impaired cognitive performance, behavioural and motor development' as well as coordination, language development and scholastic achievement increasedmorbidity from infectious diseases' to Despite such dire implications, our public policy has not yet been able there is pfotect sevenry per cent of chjldren from becoming anaemic.l3 V/hile of anaemia among children no palpable g.rrd.r difference in the prevalence (thegap widens ^t ^l^tef stage), there is a close linkage with the anaemra status from of tn.it mothers. Almost fifty-five per cent of women in India suffer some kind of anaemia. That the social underdogs afe more vulnerable to ^n emia can be seen from is of the NFHS data. For example, in \flest Bengal the highest :ra;te anaemia (78 per cent) and correlatively found among Scheduled Tribe or adivasi v/omen Scheduled Tribe children (86 per cent)14,thus establishing the "lso "-ong relationshif between a mother's health and that of her biological child' Similar of pattern is evident in the neigbouring states.It is observed that this prevalence with an improvement rvith inctease in female literacy and also anaemiadecteases quintile status. Promoting female htetacy,therefore, appears to be in the wealth one maior social intervention in our attempt to enhance equity in health.

and economic classes Table 4.42 Prevalence of Anaemia among women from different social grouPs

A Vrri;ln

There appears a wide gender gap in anaemia among adults: while anaemia among women in the country is 55 percent it is found tobe 32 per cent among men. The statesunder consideration,all exlubit a similat pattetn (exceptingM*ip* discussed in detarl in the previous section). Again, anaemiais found to be higher in rural areas,among children with illiterate parentage,men, women and children belonging to scheduledcaste and scheduledtribe communities, and, obviously, among the poor. Itrreunitrv iN Accrss rn l-"lEALIH{AR[ Large scalesurveyshave observed that a higher percentageof poor do not seek care when ill. The reasons vary from lack of adequate health facilities in the viciniry to long waiting times to financial reasons; thus covering the enrire gamut of inequality. A recent study has shown that people belongrng to the higher economic classesuse their personal reference to 'manage' better facilities and health c^re at the hospitals.Despite being ineligible for BPL cards,they use these cards to avail free services.rs Not much seemsto have changed over time in terms of improved accessto treatment for those who belong to the low income groups. Although services are avitlable the very focus of these public health facilities, namely, cheap and free services to the tradiuonally disadvantaged and the impoverished, has somehow become lost over time, leaving them vzith no option other than depending on the unqualified private medical practitioners for their basic healthcare requirements.Various studieshave addressedthis basic issue of the problem of accessto health care delivery. Unfortunately, however, as we can see,the picture has still remained largely the same.Age-old problems still exist within our delivery system, and despite numerous attempts, much remains to be achieved.People associated with the public health sector in India are aware that this gap can be bridged through education, remunerated work, better housing condition, better distribution of economic resources, improved quality of carein family planning and so on. Howevet the very core of the problem - efficient implementation and equrtable distribution - has even now remained a distant dream. We have discussedthis issue ofaccess in detail in the next section.

Dircrr

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Problems of Chakras and Treatment Main ImportantDocument5 pagesProblems of Chakras and Treatment Main Importantdineshgomber0% (1)

- Jesus Prayer and Nembutsu by Taitetsu UnnoDocument8 pagesJesus Prayer and Nembutsu by Taitetsu UnnoAndrew WebbNo ratings yet

- The History of Andhra Country 1000 AD 1500 ADDocument536 pagesThe History of Andhra Country 1000 AD 1500 ADCardy LinNo ratings yet

- The Story of Islamic Imperialism in India by Sita Ram GoelDocument160 pagesThe Story of Islamic Imperialism in India by Sita Ram Goelawanishup100% (2)

- Introduction to Yoga and Yogic PracticesDocument67 pagesIntroduction to Yoga and Yogic PracticesAnsh mishra100% (1)

- List of India Accredited Journalists - 2007 - Mediaa FollowuppDocument80 pagesList of India Accredited Journalists - 2007 - Mediaa Followuppqubrex178% (9)

- Laghu Jatakam PDFDocument195 pagesLaghu Jatakam PDFNarayna Sabhahit60% (5)

- Principle of Sri GuruDocument168 pagesPrinciple of Sri GuruChandraKalaDeviDasiNo ratings yet

- Isha Forest Flower May 2019Document24 pagesIsha Forest Flower May 2019Sadineni Vinay KumarNo ratings yet

- Western India Corrugated Box Manufacturers Association - Members Directory 2020Document18 pagesWestern India Corrugated Box Manufacturers Association - Members Directory 2020Dishank100% (1)

- Emvolio Pilot Strategy DocumentDocument34 pagesEmvolio Pilot Strategy DocumentPrabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Leprosy Policy BriefDocument4 pagesLeprosy Policy BriefPrabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- SCDS, Draft PolicyDocument33 pagesSCDS, Draft PolicyPrabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- MLHP Design Issues Concept Note June 24 2018Document7 pagesMLHP Design Issues Concept Note June 24 2018Prabir Kumar Chatterjee100% (2)

- BNSL 043 Block 4Document140 pagesBNSL 043 Block 4Prabir Kumar Chatterjee100% (3)

- Public Private Partnerships Booket-2018Document44 pagesPublic Private Partnerships Booket-2018Prabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- TB - Policy Brief v2Document4 pagesTB - Policy Brief v2Prabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Orientation of MAS Members On JaundiceDocument2 pagesOrientation of MAS Members On JaundicePrabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Sickle Cell Screening 21 March 2018Document2 pagesSickle Cell Screening 21 March 2018Prabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- OWH On CancerDocument24 pagesOWH On CancerPrabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Fulwari SpacesDocument44 pagesFulwari SpacesPrabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Medical CorporationDocument1 pageMedical CorporationPrabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- How To Collect HMIS Data For BlocksDocument4 pagesHow To Collect HMIS Data For BlocksPrabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Final ANM Malaria Guideline-2014Document10 pagesFinal ANM Malaria Guideline-2014Prabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- VedantaDocument1 pageVedantaPrabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- SELCO Health Workshop Concept and AgendaDocument2 pagesSELCO Health Workshop Concept and AgendaPrabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Vedanta HospitalDocument1 pageVedanta HospitalPrabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Operational Guidelines LMISDocument19 pagesOperational Guidelines LMISPrabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Arc GIS Make A MapDocument11 pagesArc GIS Make A MapPrabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Budget For One AMRIT ClinicDocument4 pagesBudget For One AMRIT ClinicPrabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Upright GMS 1977Document17 pagesUpright GMS 1977Prabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Jip (P 3T?C - 3 Lajg: Uau Ik XK Hkiifi XytDocument1 pageJip (P 3T?C - 3 Lajg: Uau Ik XK Hkiifi XytPrabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Raigarh Report PDFDocument52 pagesRaigarh Report PDFPrabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- 2 Reggie Lepcha GMS 1977Document1 page2 Reggie Lepcha GMS 1977Prabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- CEEW CG HighlightsDocument4 pagesCEEW CG HighlightsPrabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- NHM SpendingDocument8 pagesNHM SpendingPrabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Raigarh SummaryDocument30 pagesRaigarh SummaryPrabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Saharias and TBDocument20 pagesSaharias and TBPrabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Chhattisgarh Yuva015Document2 pagesChhattisgarh Yuva015Prabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Search of Gunda Dhur - 1910Document8 pagesSearch of Gunda Dhur - 1910Prabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- 18 Define Custom and Essentials of A Valid Custom. Discuss Its Importance As A Source of Law and Also Compare With PrecedentsDocument4 pages18 Define Custom and Essentials of A Valid Custom. Discuss Its Importance As A Source of Law and Also Compare With PrecedentsAmanKumarNo ratings yet

- SSC Mock Test Paper - 158Document22 pagesSSC Mock Test Paper - 158DeepNo ratings yet

- Report on the Public Distribution System in HaryanaDocument118 pagesReport on the Public Distribution System in HaryanamansiNo ratings yet

- Plan InfluDocument108 pagesPlan InfluRaja KammaraNo ratings yet

- Courage To Stand U.G. SampleDocument23 pagesCourage To Stand U.G. SampledirectkbellNo ratings yet

- Gail Omvedt Caste and HinduismDocument2 pagesGail Omvedt Caste and HinduismPriyanshi KhandelwalNo ratings yet

- Lyrics of Bollywood Songs Under 40 CharactersDocument3 pagesLyrics of Bollywood Songs Under 40 CharactersEhetesham BaigNo ratings yet

- Tantras - of - The - Reverse - Current - 27 - Hindu - Texts - Abstracted Michael Magee PDFDocument285 pagesTantras - of - The - Reverse - Current - 27 - Hindu - Texts - Abstracted Michael Magee PDFpavan krishnaNo ratings yet

- Amrita BinduDocument4 pagesAmrita BinduSerene In0% (1)

- Personal Details and Education SummaryDocument9 pagesPersonal Details and Education SummaryshubhamNo ratings yet

- Orientation of ArokDocument7 pagesOrientation of ArokMutiya KrisantyNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Research in Indian Medicine: Ahara Vidhi - The Ayurvedic Dietary ConceptsDocument7 pagesInternational Journal of Research in Indian Medicine: Ahara Vidhi - The Ayurvedic Dietary ConceptsAleksandr N ValentinaNo ratings yet

- RolesDocument13 pagesRolesapi-3716002No ratings yet

- 100m RaceDocument2 pages100m RaceKakashi HatakeNo ratings yet

- From Sarasvati To GangaDocument6 pagesFrom Sarasvati To GangaRamji RaoNo ratings yet

- Tic Honey TirumalaDocument2 pagesTic Honey TirumalaVamshi Krishna ArigelaNo ratings yet

- All Banks and Bank Branches in India IFSC Code ListDocument4 pagesAll Banks and Bank Branches in India IFSC Code ListsraguNo ratings yet

- South Indian actress Amala Paul's career and personal lifeDocument11 pagesSouth Indian actress Amala Paul's career and personal lifeladyfromjamaicaNo ratings yet

- A Brief History of HyderabadDocument1 pageA Brief History of Hyderabadramesh_appanapalliNo ratings yet

- Analogies - NOIDocument3 pagesAnalogies - NOIraameeshNo ratings yet