Professional Documents

Culture Documents

HLS Prof. Suk Explains How To Clerk For The Supreme Court

Uploaded by

Pablo MorettoOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

HLS Prof. Suk Explains How To Clerk For The Supreme Court

Uploaded by

Pablo MorettoCopyright:

Available Formats

Professor Suk Explains How to Clerk for the Supreme Court

By Erin Archerd Published: Friday, December 7, 2007 A mix of all class years gathered in Pound 108 Monday evening to hear Professor Jeannie Suk share stories about her experience as a Supreme Court clerk and tips for the application process. In the end, she described it as an arbitrary process and recommended that people apply multiple times, since people have been accepted on the third and fourth applications. Kirsten Solberg of the Office of Career Services began the event by stressing the necessity of a U.S. Court of Appeals clerkship as a prerequisite to applying to the Supreme Court. After a quick tour of the OCS clerkships website, she introduced Professor Suk, who clerked for Judge Harry Edwards of the D.C. Circuit before going on to clerk on the high court for Justice David Souter. Suk began nostalgically, recounting the many groundbreaking cases the court had during the 2003 term, such as the Pledge of Allegiance case, Elk Grove v. Newdow, and the trio of war on terror detainee cases, Hamdi, Rasul, and Padilla. She emphasized the close friendships she formed during her clerkship. "It's an experience unrivaled in its excitement and its intensity," she said. "You eat and breathe and sleep the work. And because you can't talk to people outside, you go crazy and you become close with the people who you work with. Those 35 other people become close friends." Clerks also become close with the justices. Suk recounted how at the end of each term, Justice Souter gives each of his clerks a picture of himself and signs it "From your life long client." She reveled in the freedom she had to explore the building and interact with the justices, and spoke with sadness of the day she had to turn in her keys and identification. "You never say to yourself, what a drag, I have to go to work today," she said. "It seems magical and unreala big marble palace with beautiful everything. As a clerk, you have the run of the buildingYou'll never be allowed to walk around as you want again. It's a great privilege to be privy to the work of the court." It is important to work well with others as a clerk, said Suk, because you need to be able to talk with the other clerks about how their justices are thinking, and you have to work on a close basis with all of the staff in chambers. "They want to choose clerks who will get along with everyone in chambers," said Suk. "They care about how well liked you are by your peers." Suk divided the work of the court into three categories: certiorari petitions, death penalty work, and cases on the merits. There are thousands of cert petitions to the court each year, which are divided evenly among the justices' chambers, except for Justice Stevens's clerks, who review all of the cases, dividing them among his 4 clerks. "You have to get it right," she warned. "The justices rely on the clerks to sort through the legal issues, and if you get [something like] jurisdiction wrong, it can be terrible. And that happens."

She characterized the death penalty work as an emotionally taxing part of the job. Once or twice a week, when an execution is about to take place, a clerk is designated to review the case documents, write a memo to the justices, and wait for their life or death votes. "You're getting all the votes in and you know at the end of the day that without 5 votes, the defendant is executed," she said. "It gets very exhausting." The final group of cases, those on the merits, are the most well-known and exciting. The Court typically hears fewer than 100 a year. Clerks divide up those cases, taking each, and the length of the memo they produce can range from 40 pages all the way down to justices who don't always have their clerks write bench memos. Justice Souter asked for 2 pages and no more. Suk said that the impact the clerks had on the judges was often inversely proportional to the importance of the decision. "For the national security cases, I very much doubt that those are cases where the clerk made much difference," said Suk. "On the important cases the justices do more legwork." The clerkship experience is all-encompassing, and requires a great deal of collaborative, fast-paced work. The difficulty is that clerks can't talk to anyone outside the office about the cases that are occupying all of their time. "You have no room in your brain for anything else," she said. "You feel very trapped in your own head. The other clerks are really the only people you can talk to." At the end of her lecture, Suk took questions from the audience of students. She quickly disabused them of the all-importance of grades. "Some people here think it's all over after the first semester," she said. "People look for an upward trend, people who end strong. How you do in your first year will not lock you out of any opportunity." She even shared an example of a strong candidate who received a clerkship without even applying. The woman was reluctant to apply because she was not a straight-A student, but a professor called a justice and secured her a clerkship. Suk described the common belief that there are certain "feeder judges" to the Supreme Court as a "little bit of a myth." "It's a circular process because those appellate judges compete for the strongest students at places like Harvard," she said. "The majority of clerks each year are not coming from feeder judges. There's no royal road to the Supreme Court." Law review is an activity that most clerks have in common, but according to Suk, judges look for it as a show of writing experience. You can get that experience by researching for a professor, or publishing in other journals. What is important is the writing and editing experience. One of the most important elements of the application is the recommendation of your professors. "If you're a 1L, start talking in class so they know who you are," Suk advised. "Try to do the best that you can, and get to know your professors by going to office hours to talk about ideas. The goal is not to go in, sit down, and hang outYou want the professor to be able to refer to specifics about you." The element all of her co-clerks had in common was researching for a professor, though she cautioned students to keep things under control. "The worst thing is to take on too much and not have time to study for exams," she said. "You need to be a good planner and able to handle all the things you're doing in law school."

Suk cautioned students about using summer employers as recommenders, unless you have done excellent work for a partner with a relationship with a justice. She also recommended waiting to apply until "your application is at its highest point." "If you think that 3L last semester will be important, or if you think you will have a strong letter from the judge you clerked for below, then that's good strategy as well," she said. "Definitely apply multiple times, but only after you're really strong." Clerking is not a family friendly experience, at least not at the time. "My year 5 had children, and the year after all of us had kids," she said. "Being young helps because it's exhausting. Lots of the moms and dads never saw their children." On the other hand, there are no classes in law school that Suk felt students had to take, though classes like criminal procedure and federal courts can be useful. "I truly believe there is nothing you can't teach yourself," she said. "If you are a strong legal thinker, I don't think there's anything you can't figure out." All in all, there is a lot of randomness and luck in the application process. Suk noted that there have been people "with everything" - a Sears Prize, a feeder judge clerkship, and research for professors - who have not gotten a clerkship. She described each justice as unique to work for, and advised applicants to ask around about justices' reputations. "Working for my justice was a pleasurable year," she said. "It's intense, but he's a very good man. Of course, you're not going to have much of a choice. It's whoever offers you a clerkship and people feel lucky to be in that position." Finally, she recommended that people don't try to hide their political orientation in the belief that some justices prefer not to hire liberals or conservatives. "You shouldn't as a member of the Federalist Society put it on your resume for some judges and not for others people find out about it and talk amongst themselves," she said. "They will talk to the clerks in all the other chambers who went to Harvard, [about] whether you're a nice person, treat others with respect, how you talked in class."

You might also like

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- WIS New Hire Forms - 2022Document5 pagesWIS New Hire Forms - 2022Binh TranNo ratings yet

- Procedure of Summary Trial in IndiaDocument12 pagesProcedure of Summary Trial in IndiaKashyap Kumar Naik80% (5)

- PE v. PE (Full Text and Digest)Document3 pagesPE v. PE (Full Text and Digest)Janine OlivaNo ratings yet

- Plaintiffs' Memorandum in Opposition To Defendants' Motion To Suspend Injunction Pending AppealDocument46 pagesPlaintiffs' Memorandum in Opposition To Defendants' Motion To Suspend Injunction Pending AppealKelly Phillips ErbNo ratings yet

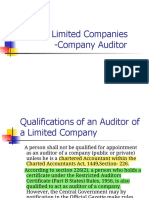

- Audit of Limited Companies - Company AuditorDocument8 pagesAudit of Limited Companies - Company AuditorAshiqul HaqueNo ratings yet

- US V Jose MontanoDocument2 pagesUS V Jose MontanoDuffy DuffyNo ratings yet

- SMP 20 Years 1 LAKHDocument3 pagesSMP 20 Years 1 LAKHTamil Vanan NNo ratings yet

- LAIR-Unit-4-course MaterialDocument20 pagesLAIR-Unit-4-course MaterialsreevalliNo ratings yet

- Himachal Pradesh E-Mail/ Regd. Public Works Department: NO - SRJ/AB/PMGSY/HP-08-39A/2018-19-Dated: - ToDocument4 pagesHimachal Pradesh E-Mail/ Regd. Public Works Department: NO - SRJ/AB/PMGSY/HP-08-39A/2018-19-Dated: - ToKULDEEP SINGH THAKURNo ratings yet

- Cometa vs. CADocument6 pagesCometa vs. CAjegel23No ratings yet

- Unit 3 JDocument6 pagesUnit 3 JKanishkaNo ratings yet

- K ' 244891 Agreement For Rent of Flat at Basundhara Residential Area (Flat: 05 Floor, House: 412, Road: 09, Block: F)Document3 pagesK ' 244891 Agreement For Rent of Flat at Basundhara Residential Area (Flat: 05 Floor, House: 412, Road: 09, Block: F)Quazi Rafiur Rahman100% (1)

- PAC vs. Lim (G. R. No. 119775 - October 24, 2003)Document5 pagesPAC vs. Lim (G. R. No. 119775 - October 24, 2003)Lecdiee Nhojiezz Tacissea SalnackyiNo ratings yet

- General Clauses Act 1897Document20 pagesGeneral Clauses Act 1897Jay KothariNo ratings yet

- Institute of Graduate Studies: Romblon State University Main Campus Odiongan, RomblonDocument3 pagesInstitute of Graduate Studies: Romblon State University Main Campus Odiongan, RomblonSir Rothy Star Moon S. CasimeroNo ratings yet

- Pro-Troll v. Shortbus Flashers - ComplaintDocument13 pagesPro-Troll v. Shortbus Flashers - ComplaintSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Tutorial Letter 102/3/2023: Semesters 1 and 2Document32 pagesTutorial Letter 102/3/2023: Semesters 1 and 2Vhulenda MaudaNo ratings yet

- P - R C & I G R: 1. Pre-Registration ContractsDocument10 pagesP - R C & I G R: 1. Pre-Registration ContractsZrieynn HalimNo ratings yet

- Proclamation of Independence 1957 PDFDocument2 pagesProclamation of Independence 1957 PDFMemori MelakaNo ratings yet

- Legal Writing Abad ReviewerDocument7 pagesLegal Writing Abad ReviewertrishaNo ratings yet

- Insurance Fraud IndictmentDocument35 pagesInsurance Fraud Indictmentxoneill7715No ratings yet

- Legal Ethics Case DigestsDocument2 pagesLegal Ethics Case DigestsIsa VivasNo ratings yet

- Due DiligenceDocument3 pagesDue Diligencedong albsNo ratings yet

- Immediate Deferred IndefeasibilityDocument15 pagesImmediate Deferred Indefeasibilityyvonne9lee-3No ratings yet

- People V Quizon DigestDocument12 pagesPeople V Quizon DigestJaypee OrtizNo ratings yet

- CT Client DP ResponsesDocument8 pagesCT Client DP ResponsesAmaya HernandezNo ratings yet

- Family TrustsDocument2 pagesFamily Trustsvsimas11No ratings yet

- Analysis of Sex-Trafficking Awareness InitiativeDocument4 pagesAnalysis of Sex-Trafficking Awareness InitiativeCarlyClendeningNo ratings yet

- 00-TOC - Workshop Notes PDFDocument2 pages00-TOC - Workshop Notes PDFsamNo ratings yet

- CFC, FSC and Tax HavensDocument14 pagesCFC, FSC and Tax Havensdigvijay bansalNo ratings yet