Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Akash 2

Uploaded by

Dheeraj JaiswalOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Akash 2

Uploaded by

Dheeraj JaiswalCopyright:

Available Formats

History Main article: History of agriculture A Sumerian harvester's sickle made from baked clay (ca. 3000 BC).

Agricultural practices such as irrigation, crop rotation, fertilizers, and pesti cides were developed long ago, but have made great strides in the past century. The history of agriculture has played a major role in human history, as agricult ural progress has been a crucial factor in worldwide socio-economic change. Divi sion of labor in agricultural societies made commonplace specializations rarely seen in hunter-gatherer cultures. So, too, are arts such as epic literature and monumental architecture, as well as codified legal systems. When farmers became capable of producing food beyond the needs of their own families, others in thei r society were freed to devote themselves to projects other than food acquisitio n. Historians and anthropologists have long argued that the development of agric ulture made civilization possible. The total world population probably never exc eeded 15 million inhabitants before the invention of agriculture.[25] [edit] Ancient origins Further information: Neolithic Revolution The Fertile Crescent of Western Asia, Egypt, and India were sites of the earlies t planned sowing and harvesting of plants that had previously been gathered in t he wild. Independent development of agriculture occurred in northern and souther n China, Africa's Sahel, New Guinea and several regions of the Americas.[26] The eight so-called Neolithic founder crops of agriculture appear: first emmer whea t and einkorn wheat, then hulled barley, peas, lentils, bitter vetch, chick peas and flax. By 7000 BC, small-scale agriculture reached Egypt. From at least 7000 BC the Ind ian subcontinent saw farming of wheat and barley, as attested by archaeological excavation at Mehrgarh in Balochistan in what is present day Pakistan. By 6000 B C, mid-scale farming was entrenched on the banks of the Nile. This, as irrigatio n had not yet matured sufficiently. About this time, agriculture was developed i ndependently in the Far East, with rice, rather than wheat, as the primary crop. Chinese and Indonesian farmers went on to domesticate taro and beans including mung, soy and azuki. To complement these new sources of carbohydrates, highly or ganized net fishing of rivers, lakes and ocean shores in these areas brought in great volumes of essential protein. Collectively, these new methods of farming a nd fishing inaugurated a human population boom that dwarfed all previous expansi ons and continues today. By 5000 BC, the Sumerians had developed core agricultural techniques including l arge-scale intensive cultivation of land, monocropping, organized irrigation, an d the use of a specialized labor force, particularly along the waterway now know n as the Shatt al-Arab, from its Persian Gulf delta to the confluence of the Tig ris and Euphrates. Domestication of wild aurochs and mouflon into cattle and she ep, respectively, ushered in the large-scale use of animals for food/fiber and a s beasts of burden. The shepherd joined the farmer as an essential provider for sedentary and seminomadic societies. Maize, manioc, and arrowroot were first dom esticated in the Americas as far back as 5200 BC.[27] The potato, tomato, pepper, squash, several varieties of bean, tobacco, and seve ral other plants were also developed in the Americas, as was extensive terracing of steep hillsides in much of Andean South America. The Greeks and Romans built on techniques pioneered by the Sumerians, but made few fundamentally new advanc es. Southern Greeks struggled with very poor soils, yet managed to become a domi nant society for years. The Romans were noted for an emphasis on the cultivation of crops for trade. In the same region, a parallel agricultural revolution occurred, resulting in so me of the most important crops grown today. In Mesoamerica wild teosinte was tra

nsformed through human selection into the ancestor of modern maize, more than 60 00 years ago. It gradually spread across North America and was the major crop of Native Americans at the time of European exploration.[28] Other Mesoamerican cr ops include hundreds of varieties of squash and beans. Cocoa was also a major cr op in domesticated Mexico and Central America. The turkey, one of the most impor tant meat birds, was probably domesticated in Mexico or the U.S. Southwest. In t he Andes region of South America the major domesticated crop was potatoes, domes ticated perhaps 5000 years ago. Large varieties of beans were domesticated, in S outh America, as well as animals, including llamas, alpacas, and guinea pigs. Co ca, still a major crop, was also domesticated in the Andes. A minor center of domestication, the indigenous people of the Eastern U.S. appea r to have domesticated numerous crops. Sunflowers, tobacco,[29] varieties of squ ash and Chenopodium, as well as crops no longer grown, including marshelder and little barley were domesticated.[30][31] Other wild foods may have undergone som e selective cultivation, including wild rice and maple sugar. The most common va rieties of strawberry were domesticated from Eastern North America.[32] By 3500 BC, the simplest form of the plough was developed, called the ard.[33] B efore this period, simple digging sticks or hoes were used. These tools would ha ve also been easier to transport, which was a benefit as people only stayed unti l the soil's nutrients were depleted. However, through excavations in Mexico it has been found that the continuous cultivating of smaller pieces of land would a lso have been a sustaining practice. Additional research in central Europe later revealed that agriculture was indeed practiced at this method. For this method, ards were thus much more efficient than digging sticks.[34]

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Making of CheeseDocument5 pagesMaking of CheeseManish JhaNo ratings yet

- Eat Your Fruit and Veggies - Crossword 2Document2 pagesEat Your Fruit and Veggies - Crossword 2TabbyKatNo ratings yet

- Seed Treatment With Liquid Microbial Consortia For Germination and Vigour Improvement in Tomato (Solanum Lycopersicum L.)Document6 pagesSeed Treatment With Liquid Microbial Consortia For Germination and Vigour Improvement in Tomato (Solanum Lycopersicum L.)Shailendra RajanNo ratings yet

- Flora &faunaDocument2 pagesFlora &faunarajesh0005No ratings yet

- November 2021 (v3) QP - Paper 2 CAIE Biology IGCSEDocument16 pagesNovember 2021 (v3) QP - Paper 2 CAIE Biology IGCSEanahmadNo ratings yet

- Fern Grower's Manual - Revised and Expanded Edition PDFDocument605 pagesFern Grower's Manual - Revised and Expanded Edition PDFLuis Pedrero100% (6)

- Leekchi: Aube Giroux Kitchen Vignettes Taproot MagazineDocument2 pagesLeekchi: Aube Giroux Kitchen Vignettes Taproot MagazineThorNo ratings yet

- E289 CD 01Document12 pagesE289 CD 01Muhammad ImranNo ratings yet

- Get Our Special Grand Bundle PDF Course For All Upcoming Bank ExamsDocument25 pagesGet Our Special Grand Bundle PDF Course For All Upcoming Bank Examssachin kambhapuNo ratings yet

- ActaSucculenta 1 1 2013 EN PDFDocument107 pagesActaSucculenta 1 1 2013 EN PDFJiří VítekNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Carbon Sequestration by Dominant TreesDocument11 pagesAnalysis of Carbon Sequestration by Dominant TreesFarjad KhanNo ratings yet

- Elementary Statistics 9th Edition Weiss Solutions ManualDocument24 pagesElementary Statistics 9th Edition Weiss Solutions ManualDustinMahoneyidbj100% (27)

- Lesson 11 BPPDocument20 pagesLesson 11 BPPMa LeslynneNo ratings yet

- Century Dinner MenuDocument1 pageCentury Dinner Menusupport_local_flavorNo ratings yet

- Comparative Assessment of Gender Roles in Agroforestry Management in Orlu Local Government Area of IMO State, NigeriaDocument26 pagesComparative Assessment of Gender Roles in Agroforestry Management in Orlu Local Government Area of IMO State, NigeriaPORI ENTERPRISESNo ratings yet

- Hager Et Al (2014)Document9 pagesHager Et Al (2014)Vitoria Duarte DerissoNo ratings yet

- Adulteration and Evaluation of Crude DrugsDocument48 pagesAdulteration and Evaluation of Crude DrugsVikash KushwahaNo ratings yet

- Determining The Best Growing Seeds G5Document15 pagesDetermining The Best Growing Seeds G5Deasserei TatelNo ratings yet

- Cell Structure and FunctionsDocument19 pagesCell Structure and Functionsrazen sisonNo ratings yet

- 1ST EngDocument3 pages1ST EngirfanNo ratings yet

- Test BaruDocument4 pagesTest BaruDonnie AlulNo ratings yet

- PatolaDocument7 pagesPatolaJean SuarezNo ratings yet

- Serpentine Soils PDFDocument36 pagesSerpentine Soils PDFHery LapuimakuniNo ratings yet

- Herbal MedicinesDocument36 pagesHerbal MedicinesJojo Mcalister0% (1)

- Student Activity Sheet - PhotosynthesisDocument1 pageStudent Activity Sheet - PhotosynthesisfaeznurNo ratings yet

- Opium - Poppy Cultivation, Morphine and Heroin ManufactureDocument11 pagesOpium - Poppy Cultivation, Morphine and Heroin Manufactureskalpsolo75% (4)

- Reading Comprehension Comparison Degree of Quantity Asking For PermissionDocument30 pagesReading Comprehension Comparison Degree of Quantity Asking For PermissiontamansiswaNo ratings yet

- Bioreactor InnovaciónDocument15 pagesBioreactor InnovaciónRenato Rojas DominguezNo ratings yet

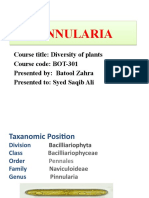

- Pinnularia PresentationDocument10 pagesPinnularia PresentationIjaz Ahmed100% (1)

- Presentation EIL Project by JMV LPSDocument59 pagesPresentation EIL Project by JMV LPSMahesh Chandra ManavNo ratings yet