Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Police of Civilization The War On Terror As Civilizing Offensive

Uploaded by

Contributor BalkanchronicleOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Police of Civilization The War On Terror As Civilizing Offensive

Uploaded by

Contributor BalkanchronicleCopyright:

Available Formats

International Political Sociology (2011) 5, 144159

The Police of Civilization: The War on Terror as Civilizing Offensive

Mark Neocleous Brunel University

This article deals with two contemporary issues: the return of civilization as a category of international power and the common refrain that war is now looking more and more like a police action. The article shows that these two issues are deeply connected. They have their roots in the historical connection between civilization and police. Through an exercise the history of ideas as an essay in international political sociology, the article unravels the connection between these issues. In so doing, it suggests that a greater sensitivity to the broader police concept in the original police science might help us understand the war on terror as a civilizing offensive: as the violent conjunction of war and police.

The process of civilization has been fetishized. Max Horkheimer

Civilization is back. The war on terror is said be about many things: freedom, democracy, and free enterprise, as the US National Security Strategy of 2002, puts it. Or, as found in other quarters, values, civil society, the rule of law, and a way of life. A regular item on such lists is civilization. This view is found far and wide and in a variety of discursive forms. According to the National Security Strategy, the war on terror is not a clash of civilizations, but the allies of terror are the enemies of civilization. This attempt to distance the strategy from the more politically awkward clash of civilizations thesis merely underlines the claim that it is still civilization that is ultimately at stake. We are living, suggests the Strategy, in an age when the enemies of civilization openly and actively seek the worlds most destructive technologies (National Security Strategy of the United States of America 2002:vi, 31, 15). This is the view that was very quickly asserted by President Bush during the early stages of the war. In an Address to a Joint Session of Congress and the American People on September 20, 2001, Bush commented that the war was not Americas ght; rather, this is civilizations ght. Hence, America was not ghting alone, because the the civilized world is rallying to Americas side (Bush 2001; also see Bush 2004). Likewise, Colin Powell described the purpose of the war as the defeat of those attacking civilization (Powell 2001). One nds similar comments made elsewhere by other Western leaders: German Chancellor Schro der, for example, called 9 11 a declaration of war against all of civilization (Schroder 2001). The idea also runs through a range of other documents, from former New York mayor Rudy Giulianis comment that youre either with civilization or the terrorists (2001), through the publication by the American Council of Trustees and Alumni on how universities are undermining Western democracies, called Defending Civilization and published as part of their Defense of Civilization Fund (2002). The list of examples could go on and on.

doi: 10.1111/j.1749-5687.2011.00126.x 2011 International Studies Association

Mark Neocleous

145

Civilization, then, is back; and it is back in the context of global war. One way of grappling with this return is to point to the fact that, read in terms of international law, it appears to be a rather embarrassing anachronism. In his account of the emergence of civilization as the standard of international law in the nineteenth century, Gong (1984:69) suggests that given the contemporary consensus that all countries are now to be considered civilized, the distinction between civilized and uncivilized has declined in relevance. It made sense in the nineteenth century when racial differences between civilization and its others were at the forefront of European thought, but makes no sense now, in these postcolonial days of universal human rights. Anti-colonial movements and postcolonial states argued long and hard through the second half of the twentieth century that states should not be discriminated against on the basis of some standard of civilization rooted in the heyday of imperialism, and succeeded in attempts to pass United Nations Resolutions and Declarations to such effect. This was accompanied by a developing body of Third World Approaches to International Law which, harnessing the insights of critical theory, Marxism, race theory and post-colonial studies, challenged some of the key categories of international law. The outcome was that textbooks and international organizations were no longer suggesting that the idea of civilization was the foundation stone for international law; Lauterpacht, for example, challenged the idea in his Recognition in International Law of 1947, and the International Law Commission gradually refrained from referring to civilized countries (1947:31; also Gong 1984:90). This was compounded by the fact that by the late-twentieth century the idea of civilization had been displaced by and in part subsumed under two other ideas: one was a new standard of human rights: internationally recognized human rights have become very much like a new international standard of civilization, notes Donnelly (1998:1, 16); the other was a logic of modernity and, latterly, globalization, incorporating assumptions about standards of living, health care and related expectations: rather than being uncivilized, countries are now considered unglobalized, notes Fidler (2000). One way of dealing with the current return of civilization, then, is to show that it is indeed a rather embarrassing anachronism, harking back to a time when civilization was one of colonialisms most powerful ideological tools, providing the rationale for war, conquest, and expropriation. It is, after all, a relatively easy task to situate and criticize civilization in terms of a long history and use of binary oppositions through which political thought has been articulated and political action carried out: good evil, West East, modern primitive, and so on (Llorent 2002; Salter 2002; Bowden 2009). Yet to dismiss the return of civilization as an ideological anachronism or a form of Western hypocrisy would be to close ourselves off from some of the interesting political issues at stake. The interesting issues arise when we note that although the return of civilization has occurred in the context of a new global war, many of the actions historically understood under the category war are now being discussed through alternative categories. War no longer exists, notes General Sir Rupert Smith in a book on the modern art of war (2001:1). Or as Anthony Cordesman puts it in a report for the Washington-based Center for Strategic and International Studies: it may be that one of the lessons of modern war is that war can no longer be called war (2003:59). But if it is not war, then what is it? In 2006, the US Army and Marine Corps updated their Counterinsurgency Field Manual for the rst time in 25 years, partly as a response to the increasing importance of categories such as insurgency and counter-insurgency, lowintensity conict, operations other than war and the gray area phenomenon. These are very much ways of describing forms of war but they are also very much a reference to internal mechanisms of social ordering; that is, to

146

The War on Terror as Civilizing Offensive

mechanisms of police. Hence, the Manual comments that warghting and policing are dynamically linked and that the roles of the police and military forces blur (2006:Sects. 695, 726). The Manual was building on a growing consensus toward this point of view. For example, a 1994 document put out by the US Department of Justice and the Department of Defense had noted a new understanding between the elds of war and police and thus argued for a growing convergence between the technology required for military operations and the technology required for law enforcement (Department of Defense and Department of Justice 1994:Sect.I, Pt. B). This tendency has been reinforced with the reconguration of the war on terror as counterinsurgency, one of the features of which is the criminalization of the enemy (the unlawful combatant replacing the soldier in battle). At the same time, many have sought to rethink the political agenda surrounding war by pointing to the tendency in question. Whether in the use of rather loose concepts such as world policeman, sheriff, global gendarme, globocop, soldiers as cops, and so on, the assumption among commentators of very different political persuasions seems to be that war is increasingly as much a form of police as it is military engagement. For Badiou (2003:153155), governments now oppose terrorism within the symbolic register of policing. For Agamben (1993:61) a particularly destructive jus belli cloak[s] itself in a seemingly modest police operation, while for Hardt and Negri, war is reduced to the status of police action, with the United States acting as the international police power (2000:1213, 39, 180, 181; also Hardt and Negri 2004:14). For Mladek (2007:231), the increasingly worldwide civil war leaves us with a continuous police interventions aimed at producing security within a single global territory. This is a view found across the political spectrum (for example: Boot 2002:xx, 350; Bronson 2002; Caygill 2003; Ignatieff 2003; Salt and Smith 2008; Gray 2009). Yet despite this growing consensus connecting war and police, there has been a marked unwillingness to think through precisely what the connection means. Police is still rather narrowly dened in terms of law enforcement, and thus the focus has been really on the question of how, if at all, the military model and the criminological model can be brought together (Andreas and Price 2001; Simon 2007:280; Chesney and Goldsmith 2008). In this peace-keeping as police-keeping or criminology meets international relations (IR) approach, little is said about the idea of police beyond the question of crime and lawenforcement. The general assumption running through this literature is that the role of police-keeping is to pre-empt and combat ethnic, religious and political violence, as well as economic crime and also to police regular crime, including that related to property and public order (Day and Freeman 2003:300). In this article, I aim to connect the developing issues surrounding the coming together of war and police with the return of the idea of civilization. I suggest that we can make sense of the return of civilization by tracing it as an idea back to the original police science; that is, to police not as crime prevention and lawenforcement, but in terms of the more general process of administration and government. The idea of police as narrowly concerned with crime prevention and law-enforcement was a meaning imposed on the term by an increasingly hegemonic liberalism in the late-eighteenth century. Prior to this, police connoted order and thus held an incredibly broad compass, extending from crime and law enforcement through to the regulation of trade and commerce, disciplining labor, education, the minutia of social life and, of course, breaches of the peace (see Neocleous 2000). Police science was, in effect, the science of governing and a form of pastoral power (Foucaults term) over the population; as an active intervention in and disciplining of the population it constituted nothing less than the fabrication of order. There is now a fairly substantial body

Mark Neocleous

147

of work, stemming from Foucault, which has sought to mobilize this original concept of police for new insights in political and historical sociology (for example: Knemeyer 1980; Tribe 1984; Minson 1985; Gordon 1991; Dean 1999; Pasquino 1991; Dubber 2005). However, aside from a couple of limited attempts (see Walters 2002; Dean 2006),1 it has not been widely used to grapple with the international dimension of police powers or what it means to speak of war and police coming together. Symptomatically, the special section of a recent issue of International Political Sociology (the second issue of Volume 4, published in 2010), stemming from a roundtable discussion at the 2009 International Studies Association conference, asks about the relationship between Foucault and IR, and yet not one of the seven contributions raises the possibility of connecting the current question of war police with the huge body of work on police inspired by Foucaults insights into this concept. The same is true of the much wider literature aiming to connect Foucault to IR or international studies (such as Weber 1994; Bartelson 1995; Hutchings 1997; Selby 2007, who does mention police but only in citing Hardt and Negri; Evans 2010). This absence of discussion perhaps goes some way to explaining why the narrower, more commonsensical and liberal notion remains in place. The reach of this article is thus broad and its conclusions fairly speculative, as it connects an issue in contemporary international political sociology with a problematic in the history of ideas. Essentially, I want to connect the concept of civilization to the logic of police by pointing to the role of civilization-as-police in the fabrication of international order. I do so by making a historical return to the question of police in a conceptual history designed on the one hand to make sense of the original emergence of civilization as a political category and, on the other hand, to help identify what might be at stake when people are talking about the elision of war and police in the global war on terror. In his account of civilization as an imperial idea, Brett Bowden comments that civilization is a concept that is used to both describe and shape reality (2009:8). I argue that this power to shape reality stems from civilizations historical roots in the police idea; furthermore, I suggest that this helps explain why these terms have once more come to the fore. In the context of a new liberal dream of global capitalism and world order organized through military power, the logic of civilization and the growing importance of police turn out to be supremely apt. Civilization International Law The use of civilization in the war on terror hints at a long history of the term in international law, but also proposes a rather obvious and crude political distancing from the major enemy in this war. This combination can be seen in a brief outline of the importance of civilization in international law as it emerged in the nineteenth century. Gong (1984:25) suggests that the roots of civilization as a standard in international law are documented by two historical records: on the one hand, the nineteenth-century treaties signed between European and non-European countries, and, on the other hand, the legal texts written by the leading international lawyers of the era. In fact, there was a third dimension, namely liberal political thought more generally. In an essay in the London and Westminster Review in 1836, John Stuart Mill comments that civilization has a double meaning:

1 It is also worth noting that the second edition of Deans Governmentality (2010) tries to develop the idea of police beyond the question of pastoral power in the rst edition and onto the international organization of population. However, the discussion is somewhat limited (pp. 244245).

148

The War on Terror as Civilizing Offensive

It sometimes stands for human improvement in general, and sometimes for certain kinds of improvement in particular. We are accustomed to call a country more civilized if we think it more improved; more eminent in the best characteristics of Man and Society; farther advanced in the road to perfection; happier, nobler, wiser. But in another sense it stands for that kind of improvement only, which distinguishes a wealthy and powerful nation from savages and barbarians. (1977:119)

The concept thus concerns a level of productive life and a degree of cultural sophistication, and it is these features that generate the possibility of international comparison. Hence, in a later essay on international disputes in 1859, Mill comes back to the idea:

There is a great difference between the case in which the nations concerned are of the same, or something like the same, degree of civilization, and that in which one of the parties to the situation is of a high, and the other of a very low, grade of social improvement. To suppose that the same international customs, and the same rules of international morality, can obtain between one civilized nation and another, and between civilized nations and barbarians, is a grave error. (1984:118)

This was part and parcel of the liberal distinction between civilized and barbarian forms of society, and fed into the wider narrative of liberal internationalism that became the foundation of international law (Schwarzenberger 1955; Koskenniemi 2001:176). The connection lies in the links made within the liberal mind between peace and security, law and order, and civilization: law, as the gentle civilizer of nations, brings peace, security and order. The wider backdrop to this is the danger of uncivilized (primitive, savage, barbaric) communities, to be policed through the introduction of Western law and administration. Civilization thereby connected international law not just with assumptions about peace and security, but also with the political economy of human labor and free trade, liberal political institutions, and certain bourgeois standards of material conduct. In so doing, it became the main criterion by which the place and status of different human groups would be judged. The standard of civilization could be conceived only by reference to a diverse group of others, understood as enemies, and was used to distinguish those that belong to international society from those that do not (Stocking 1987:3036; Federici 1995:65; Young 1995:32). Those who fulll the requirements of the standard are brought inside a circle of members, while those who do not conform are left outside. By the end of the nineteenth century, the standard of civilization was being articulated in major Peace Conferences and key texts on international law. The Hague conference of 1899 was called for and attended by those who regarded themselves as recognizing the solidarity which unites the members of the society of civilized nations, while the 1907 conference was said to be based on the solidarity uniting the members of the society of civilized nations (Scott 1908:23, 203204). Major texts of international law conrmed this process: Oppenheims major 1905 text, for example, dened international law as the body of customary and conventional rules which are considered legally binding by civilized States in their intercourse with each other, and went on to suggest that to be admitted into the Family of Nations a state must, rst, be a civilized State which is in contestant intercourse with member so of the Family of Nations (Oppenheim 1905:3, 31). As much as it was about law, however, civilization was also very much about war, not least in the various attempts to codify the rules of civilized warfare and imperial power. Article 6 of the Berlin Conference of February 1885, in which the imperial powers decided how they would carve up Africa, held that

Mark Neocleous

149

each of the powers should aim at instructing the natives and bringing home to them the blessings of civilization. As Charles Alexandrowicz points out:

A review of documents in the principal collections of African treaties would reveal that the transfer of sovereign rights or titles by the African rulers to the protecting European Powers was either expressly or implicitly connected to the duty of civilization, i.e., the task of the transferee to assist African communities in achieving a higher level of civilization before they re-entered the family of nations as equal sovereign entities. (1971:154)

This inner imperial and bellicose truth meant that by the end of the nineteenth century the logic of civilization had lost its European and Christian dimensions. The entry of the United States into international society broke the European stranglehold and the inclusion of non-Christian but nonetheless imperial powers such as Japan meant that what had been understood in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries as the law of Christian nations or the public law of Europe had by the end of the nineteenth century become redened as the international law of civilized nations, revealing that what was of ultimate importance for civilization was not European Christianity but imperial warfare and military intervention (Tucker 1977:9; Gong 1984:5, 15, 23, 54, 164). This was again reected in the legal textbooks of the time. Hence, Elias is right to note that it is not a little characteristic of the structure of Western society that the watchword of its colonizing movement is civilization (Elias 1978b:313). The idea of civilization in international law, then, is widely accepted to be a product of nineteenth-century developments in the concept of civilization and the widening of the net of international law. There was widespread agreement that the general principles of law were those recognized by civilized nations, with implicit or explicit assumptions about the rule of law, respect for fundamental liberties including the right to property, and the possibility of diplomatic exchange and communication. Within this, the distinction between civilized and uncivilized was simply assumed to be acceptable (Schwarzenberger 1976:84; Gong 1984:73). The standard of civilization thus never really required articulating per se, as its function was clear: to establish a taxonomy through which states could be granted legal personality in international society. It is easy to see how and why such taxonomy would come to be criticized: by being easily connected with race and racial classication it was part and parcel of a global race warwitness, as just one example, Darwins comment (2004:183) that at some period the civilized races of man will almost certainly exterminate, and replace, the savage races throughout the world. There is, however, more to be said about the term than the focus on nineteenth-century international law allows. Civilization Police Civilization seems to us like such an old word. This impression is in part achieved by its root in civil, from civilis, connected to the Latin citizen. Civil was thus used from the fourteenth century onward, connected to civility and civilize, and morphing into civil society in the seventeenth century. But civilization in fact came into the language only very recently, in the second half of the eighteenth century (Febvre 1973:220; Williams 1976:48). The reason why it came into the language at this time is important for the argument here. In France, the rst recorded use of the term would appear to be in the Marquis de Mirabeaus LAmi des hommes ou Traite de la population, rst published in 1757. From then on, writers increasingly came to use the term in the sense used by Mirabeau: rst, to refer to the process through which humanity emerged from

150

The War on Terror as Civilizing Offensive

barbarity and, second, as a state of society, of which various examples might then be found (Benveniste 1971:290291). In so doing, it built on much older terms such as the participle civilise (civilized), and the verb civiliser (to civilize), together taking us back to the idea of renement and its cultivation. Febvre (1973:222223) suggests that from 1765, the term becomes increasingly naturalized and forces its way into the Dictionnaire de lAcademie francaise in 1798. One of its main themes seems to have been modes of behavior. Prior to the emergence of civilization, concepts such as politesse or civilite were used to express the self-image of the European aristocracy. Civilise was, like cultive, poli, or police, one of the terms by which the courtly elite designated the specic quality of their behavior, renement, and social manners in contrast to the lower orders (Elias 1978a:39). In its emergence in the second half of the eighteenth century, however, civilization was very closely associated with rising social movements challenging the power of this aristocracy. Elias (1978a:49) comments that the French bourgeoisiepolitically active, at least partly eager for reform, and even, for a short period, revolutionaryremained strongly bound to the courtly tradition in its behavior and its affect-molding even after the edice of the old regime had been demolished. In terms of social origins then, the concept of civilization developed in France within the opposition movement in the second half of the eighteenth century; the civilizing process became a project of the bourgeois class. The French concept of civilisation reects the rising importance of the bourgeoisie in that country, becoming a key instrument in dealing with internal conict and for articulating a vision of a new world. For this, terms such as civilite were a little too static (Benveniste 1971:289292; Elias 1978a:38, 49, 103). At the same time, however, in the work of Quesnay and the physiocrats, the idea emerged that society and the economy have their own laws which are never fully manageable by rulers, and thus that enlightened administration should govern in accordance with the laws of political economy. As Cheytz notes (1993:116), the distinction between civilization and its other, the savage barbarian, is one of the fundamental ctions of the history of private property. This had an exact parallel in England, where civilization also proved to be a crucial ideological tool of a rising industrial class and its key thinkers. Like the French, the English civilize and civilized are much older than civilization, which again appears for the rst time in the same period as in France. The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) lists as one of the earliest written usages an entry by Boswell in his Life of Johnson. There, Boswell reports a visit to Johnson in 1772, in which the latter is found preparing a new edition of his Dictionary: On Monday, March 23, I found him busy, preparing a fourth edition of his folio Dictionary He would not admit civilization, but only civility. With great deference to him, I thought civilization, from to civilize, better in the sense opposed to barbarity, than civility (Boswell 1999:331). Boswell was picking up on the new word that was then coming to the fore. The fact that Boswell thought civilization worth entering as distinct from civility suggests a reasonably well-established difference between civility, in the sense of manners and politeness, and civilization, as the opposite of barbarity. Resisting the modern, Johnson preferred the older civility but Boswell, as a Scotsman with legal training, was perhaps trying to identify a term which captured the French concern for manners (civility) with the Scottish commitment to Civil Law (the OED notes one meaning of the term as being the assimilation of common law to civil law), and the transformation of the Scottish people from clansmen and cattle ranchers to merchants and bankers (Benveniste 1971:293; Caffentzis 1995:32). That it is unlikely that Boswell was doing little more than picking up a term that was already in use is suggested by the use of the term in, for example, Adam Fergusons Essay on the History of Civil Society (1767), where on the rst page Ferguson comments that

Mark Neocleous

151

where the individual advances from infancy to manhood so the species advances from rudeness to civilization, and which is then used to construct the history of civil society through the rest of the book (Ferguson 1966:1; also 232). Civilization also appears in Ashs English Dictionary in 1775 and Adam Smith felt comfortable making use of the term in the Wealth of Nations, published in 1776 (Smith 1979:706708).2 It is therefore clear that the term is a product of the second half of the eighteenth century and has a variety of senses. First, the sense that it is somehow equivalent to civility, drawing together various dimensions of the ideas of civilized and civilizing, including politeness in manners; second, it refers to a condition of civilization, a stage in history beyond barbarism and savagery; and, third, it refers to a process (Collingwood 1942:286). This idea of process is important here, for it marks civilization not merely as a state or a set of manners, but as an action to be actively carried out; indeed, to be carried out politically. Websters American Dictionary of the English Language, published in 1828, has as its rst entry for civilization: the act of civilizing. Thus, the term enters the rhetoric of power as a political mission (eventually, of course, becoming the civilizing mission) or declaration of political intent. This was a period in which in both France and England a large number of nouns ending in -ation were formed from verbs ending in -iser: centralization, democratization, francization, fraternization, nationalization, utilization and, of course, industrialization. Taking on board the fact that words ending in -ation also suggest the presence of an agent, it is clear that the agency behind the process transcended the individual, especially the idea of the individual implicit in the older aristocratic notion of civilise (Elias 1978a:44, 47, 104; Bauman 1987:8990; Starobinski 1993:2). In other words, we can see behind the idea of civilization a new historically emerging collective agency carrying out a historical process. In its origins, then, civilizations central connotation might be thought of as a nineteenth century standard (legal, cultural or otherwise), but the term in fact connoted a distinctly political project borne out of the bourgeois reform movements of the second half of the eighteenth century. Herein lay the terms essentially newessentially moderndimension, referring to the process of generating a specic stage of social development characterized by private property, money, commerce and trade. Civilization thereby became associated with a certain vision of humanity and order, useful as a criterion in political judgment, not least in defending the civilized order from its monstrous other, the savage barbarian, but useful more than anything else as the basis of bourgeois rule. As a key concept of the ruling ideology, the process of civilization becomes fetishized, as Horkheimer puts it (Horkheimer, in Adorno and Horkheimer 2010:33). Yet there is a further dimension to the term about which little is said but which is far more revealing: police. Throughout the whole of the seventeenth century, Febvre notes (1973:225), French authors classied people according to a hierarchy which was both vague and very specic.

At the lowest level there were that sauvages. A bit higher on the scale, but without much distinction being made between the two, there come the barbares. After which, passing on from the rst stage, we come to the people who possess civilite, politesse and nally, good police.

As civilization comes to take its place within the political lexicon, one of the key words from which it develops, and which functions more or less as its

2 Benveniste (1971:294) talks of the free use of the word by Smith, but this is too strong a claim: Smith uses the term civilization just three times, compared to a much wider use of civilized. For wider background to the Scottish context see Pagden (1988).

152

The War on Terror as Civilizing Offensive

midwife, is police. Febvre notes that in his essay De la felicite publique and in his work on Considerations sur le sort des hommes dans les differentes epoques de lhistoire, the rst volume of which appeared in Amsterdam in 1772, Father Jean de Chastellux uses the word police a great deal but never, so it appears, civilisation (Febvre 1973:223). Indeed, Febvres attempt to identify the rst use of the term in France shows that many of the assumed rst usages of civilization turn out to have been references to police; this nding is conrmed by Elias. For example, although Turgot is widely assumed to have been the rst to use civilization, the appearance of the term in his work was the responsibility of later editors. Turgot does not use the word civilization, says Febvre. He does not even use the verb civiliser, or the participle civilise, which was then in current use. Rather: he always keeps to police and to police. Likewise, Febvre continues, people often think that the word rst appears in Boulangers Antiquite devoilee par ses usages (1766). Yet the appearance of the word civilization in that text was placed there by Holbach, who edited the work after Boulangers death in 1759 (the Antiquite devoilee being a posthumous work). Of the Recherches sur lorigine du despotisme oriental (1761), also sometimes suggested as containing the rst use, civilise does appear in it, but fairly infrequently; civilisation never does; police and police are the usual terms (Febvre 1973:221222; Elias 1978a:39). In some writers, civilization really does replace police. Writing of Mirabeaus use of the term, Benveniste (1971:291) says that for Mirabeau civilisation is the process of what had been up until his time called police in French. That is, it refers to an act tending to make man and society more police [orderly]. In others, however, there is an oscillation between the two terms: Voltaire, in The Philosophy of History (1766), shifts from police to civilise and back again, and at one point writes of peoples becoming united into a civilized [civilise ], polished [police ], industrious body (1965:31, 40, 89). As Febvre notes, Voltaire still requires the two words. The historical picture is thus a little complicated. Although in both France and England the verb civiliser civilize and the participle civilise civilized take us back to the idea of renement and its cultivation, whereas police is derived from the Greek polis, politeia and gives us politie and police, there is no doubt that what was at stake in civilization as it emerges was very much connected to what was at stake in police. And so, as much as police gives rise to civilization, the former term continues to permeate the latter term, circulating around it and through it. On the one hand, the tendency was such that by the end of the century, two words were no longer necessary for some people. Volney in Eclaircissements sur les Etats-Unis, in 1803, could write that:

By civilisation we should understand an assembly of men in a town, that is to say an enclosure of dwellings equipped with a common defence system to protect themselves from pillage from outside and disorder within. The assembly implied the assembly implied the concepts of voluntary consent by the members, maintenance of their natural right to security, personal freedom and property: thus civilisation is nothing other than a social condition for the preservation and protection of persons and property, etc. (cited Febvre 1973:252n1)

This is civilization as police, yet no longer articulated as police. The substance of civilization has assimilated all the substance of the word police. Likewise, in a text such as Adam Fergusons Principles of Moral and Political Science, civilization connotes the basic ideas associated with police: peace and good order, security of the person and property, good order and justice (1792:207, 252, 304). But words rarely shake off their histories completely. Just as civilization could never fully lose its connections with politesse or civilite, so it could never lose its links to police. Thus, in spite of all, police resisted, notes Febvre,

Mark Neocleous

153

adding that then there was police lying behind it which was a considerable nuisance to the innovators.

What about civilise? They were tempted in fact to extend its meaning; but police put up a struggle and showed itself to be still very robust. In order to overcome its resistance and express the new concept which was at that time taking shape in peoples minds, in order to give to civilise a new force and new areas of meaning, in order to make of it a new word and not just something that was a successor to civil, poli and even, partly, police, it was necessary to create behind the participle and behind the verb the word civilisation. (Febvre 1973:229)

And so, on the other hand, the connections between the two terms could never quite be fully broken. Just as civilise was often used synonymously with words like cultive, poli, or police to designate certain social manners, so civilization and police were often used synonymously in the same way to designate a certain kind of order. For example, just as one of the lists in Guizots Dictionary of Synonyms runs Poli, Police, Civilise, so he also continues to include police as one of the fundamental elements of civilization (1863:566567). Behind this afnity lie a number of assumptions. First is the belief that there are always people in need of polishing, who lack the necessary polish. Necessary, that is, for an orderlythat is, well-policedsociety. Second is the idea that left to himself man is a mere savage or barbarian; left to themselves some people will fall (back) into this state. And third is the assumption that this is a group processthat polishing, avoiding barbarism or savagery, is a task of the group (Bauman 1985:8). This set of assumptions applies to the barbarians outside the domestic frame, of course, but it applies also to the members of the population who lack the necessary polish, who are close to or might fall into a state of barbarism, and who thus require working on by a civilized group. Those who require polishing, those who are disorderly, who are liable to become barbarians or savages, are those who require police. Starobinski writes that to polish was to civilize individuals, to polish their manners and language, but both the literal and the gurative senses of polish evoke ideas of order and thus the discipline and law necessary for an orderly society. The intermediate link in this chain of associations was provided by the verb policer, which applied to groups of individuals or to nations: Policer: to make laws and regulations (re `glements de police) for preserving the public tranquility (Starobinski 1993:15). Thus, the word Police worked alongside civility and politeness in the development of civilization. As the new term develops, police will not disappear; rather, it will come to play a role in the idea of civilization as a process and a political project. Those who require policing come to form the threat to civilizationthey are the ones which the whole history of liberalism from hereon will come to describe as most in need of the discipline of civilization (see Mill 1977:122; Hayek 1979:163). For all its novelty around civilization vis-a-vis civilize and civility, the rising social move` ments could not forego some notion of police. To the extent that civilization was congured as a battle waged between groups concerning manners, order, property, and culture, this battle could never quite relinquish the idea of police. Thus, by the beginning of the nineteenth century, civilization possessed a range of meanings, including, not least, a reference to habits and practices regarded as cultural. Ideas were evolving in such a way as to confer superiority not merely on peoples equipped with good police, but on peoples said to be more generally rich in bourgeois art, philosophy, and literature (Febvre 1973:228). Culture and civilization would become joined together in the minds of those thinkers and publicists for whom good order went hand-in-hand with manners and renement, art and literature, philosophy, and science. But cultural practices are merely one dimension of social ordering, and thus Febvre is right to

154

The War on Terror as Civilizing Offensive

argue that at the top of the great ladder whose bottom rungs were occupied by savagery and whose middle rungs were occupied by barbarity, civilisation took its place quite naturally at the same point where police had reigned supreme before it (Febvre 1973:232). Civilization thereby captured the meaning at the very heart of the police idea: the fabrication of social order (Neocleous 2000). The Civilizing Offensive If we accept the original meaning of police and the emergence of civilization from this concept, then the function of civilization as a standard in nineteenthcentury international law becomes much clearer: the fabrication of international order. We might say that whereas police had been the principle of social order, so civilization extended this globally. Or, to put it another way, civilization implicitly held on to its original police remit and extended it to the international realm, becoming the ordering category of international power. The oft-repeated criticisms of the standard of civilizationthat it was never easy to dene, that it was difcult to apply in practice, and that it often worked as a rather blunt instrument (Gong 1984:2122)miss two points. First, that these features are consistent with its origins in the police idea; the crusade for civilization, like the project of police, generates and uses a range of mechanisms of political administration to shape human subjectivity and order civil society. And, second, that it has always been a means of ordering international society around a certain project. The precise nature of this project was identied by Marx and Engels in the heyday of European colonization and the rise of international law:

The bourgeoisie compels all nations, on pain of extinction, to adopt the bourgeois mode of production; it compels them to introduce what it calls civilization into their midst, i.e., to become bourgeois themselves. In one word, it creates a world after its own image. (1984:488)

As Marx and Engels sought to show, the project of introducing civilization to all nations was a fundamental part of international capital. The fabrication of an international bourgeois order was a project of global scope. As a process this required, and continues to require, the exercise of organized violence. Now, one of the implications of the work of Elias and others on the civilizing process is that civilization implies the elimination of violence from the social order, or at least the monopolization and political administration of this violence by the state (Bauman 1987:91). For those invested in this word, civilization connotes peace rather than war; the savagery of the savage and barbarity of the barbarian replaced by the pacic world of civilization. Pacication and civilization came to be treated as part and parcel of the same process. Elias comments:

The civilizing of the state, the constitution, education, and therefore of broader sections of the population, the liberation from all that was still barbaric or irrational in existing conditions, whether it be the legal penalties of the class restrictions on the bourgeoisie or the barriers impeding a freer development of tradethis civilizing must follow the renement of manners and the internal pacication of the country. (1978a:48)

Plenty of examples of this can be found in the liberal tradition: Condorcet, for example, in his Vie de Voltaire (1789) comments that the more civilization spreads across the earth, the more we shall see war and conquest disappear in the same way as slavery and want (cited in Febvre 1973:233). Each of Smiths uses of civilization in the Wealth of Nations refers to the peace and security

Mark Neocleous

155

involved in its production, and the same link with peace can be seen in Fergusons Principles of Moral and Political Science, as noted earlier, or, a little later, in Mills suggestion that a people is civilized when the arrangements of society, for protecting the persons and property of its members, are sufciently perfect to maintain peace among them; i.e. to induce the bulk of the community to rely for their security mainly upon social arrangements (Mill 1977:120). In contrast to the standard liberal claim, we might cite a rather astute observation about the foundations of government in India, made in 1883 by James Fitzjames Stephens, that liberal who made a career of bringing out the implicit and uneasy assumptions of his brethren (Mehta 1999:29). The English in India, he said, are the representatives of a belligerent civilization (1883:557). The phrase, he added is epigrammatic, yet strictly true. After all, the English in India are the representatives of peace compelled by force. Stephens here grasps the point not only of English power in India, but of all imperial power carried out under the banner of civilization: these are acts of peace, compelled by force. The peace of civilization involves the transformation rather than elimination of violence. Stephens knew that peace needs to be read as a coded war, as Foucault would later put it (2003). Which is a way of saying: as much as civilization is a police process, it is also a war zone. The pacic side of civilization might point to the liberal peace but it also connotes the violence of liberal pacication (Neocleous 2010). This is why rather than speak of the civilizing process, we might be better off speaking of the civilizing offensive, an idea which points to the fact that civilization presupposes violence and aggression against those considered uncivilized (Mitzman 1987; Verrips 1987; Krieken 1990, 1999). As Rojas (2002:xiii) puts it, the very process that made civilization such a key element of the Western selfconsciousness was the very same process that authorized violence in the name of civilization. Violence simultaneously meted out against the savage and barbarian lesser breeds in the colonies and the savage and barbarian lower orders at home: both to be fought and pacied in the name of bourgeois security. From this it became clear that violence would never be fully eliminated from the social order, but would instead be monopolized by the state and used as part of its crusade to shape order, frame civil society, eliminate enemies and, ultimately, to keep the peace. The monopoly over the means of violence that is fundamental to the fabrication of social order is the core of the police power. Although such a formal monopoly over the means of violence does not exist in the international realmwhich is the very reason why so many people have found it difcult to develop the concept of international policethe violence through which this realm has been structured is obvious. It has traditionally been cast under the label war. But the exercise of this violence is nonetheless frequently thought of as carrying out the project of civilization and has more than anything sought to order the international world. Thus, whatever might be new about the new wars, the insistence that the war on terror is a war of for civilization comes straight out of the age of Clausewitz: in 1798 as Napoleon sends his troops off for the pacication of Egypt, he shouts to them Soldiers, you are undertaking a conquest with incalculable consequences for civilization (cited in Elias 1978a:4950). To say that police and war conjointly form the key activity of the project of civilization is to say nothing other than violence has remained intrinsic to the process in question. Thus, central to the idea of civilization is militarypolice terror (albeit, as civilization, a terror draped in law and delivered with good manners). What then of the problematic of war police? Dean (2006) has argued that in the terms of the original police science, we can see some important differences between police and war: police confronts a situation of disorder rather than an

156

The War on Terror as Civilizing Offensive

enemy; when police does concern an enemy, it is as a source of disorder rather than as an enemy per se. In this light, the main concern of police is the constitution of order rather than defeating the enemy. True as this is, it obscures the unifying connection between police and war: the exercise of violence. As Dean observes, peace is a much more developmental concept than victory, requiring the establishment and maintenance of order within a territory. This is the police project par excellence. Keeping the peace is precisely the kind of vague agenda that, historically speaking, has been understood as within the remit of the police power. The attempt to hold on to categorical distinctions between police or military for analytical, legal, and operational reasons (Hills 2004:9194) runs the risk of losing what is at stake in the fabrication of international order: the way war imbricates itself into the fabric of social relations as a form of ordering the world, diffracting into a series of micro-operations and regulatory practices to ensure that nebulous target security, in such a way that makes war and police resemble one another (Jabri 2007:116; Meyer 2008; The Invisible Committee 2009). From a critical perspective, the war-police distinction is irrelevant, pandering as it does to a key liberal myth. Holding on to the idea of war as a form of conict in which enemies face each other in clearly dened militarized ways, and the idea of police as dealing neatly with crime, distracts us from the fact that it is far more the case that the war power has long been a rationale for the imposition of international order and the police power has long been a wide-ranging exercise in pacication. The war on terror is thus the violent fabrication of world order in exactly the way that the original police power was the violent fabrication of social order. The war on terror, as international politics, is a form of police; civilizations return, writ large. References

Adorno, Theodor, and Max Horkheimer. (2010) Towards a New Manifesto? trans. Rodney Livingstone. New Left Review 65: 3361. (Original work published in 1966, based on a discussion of 1956). Agamben, Giorgio. (1993) The Sovereign Police. In The Politics of Everyday Fear, edited by Brian Massumi. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Alexandrowicz, Charles H. (1971) The Juridical Expression of the Sacred Trust of Civilization. The American Journal of International Law 65 (1): 149159. American Council of Trustees and Alumni. (2002) Defending Civilization: How Our Universities are Failing America and What Can Be Done About It. New York: American Council of Trustees and Alumni. Andreas, Peter, and Richard Price. (2001) From War Fighting to Crime Fighting: Transforming the American National Security State. International Studies Review 3 (3): 3152. Badiou, Alain. (2003) Innite Thought: Truth and the Return of Philosophy, trans. Oliver Feltham and Justin Clemens. London: Continuum. Bartelson, Jens. (1995) A Genealogy of Sovereignty. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Bauman, Zygmunt. (1985) On the Origins of Civilisation: A Historical Note. Theory, Culture & Society 2 (3): 714. Bauman, Zygmunt. (1987) Legislators and Interpreters: On Modernity, Post-modernity and Intellectuals. Cambridge: Polity Press. Benveniste, Emile. (1971) Civilization: A Contribution to the History of the Word. In Problems in General Linguistics, edited and translated by Mary Elizabeth Meek. Coral Gables, FL: University of Miami Press (Original work published in 1954). Boot, Max. (2002) The Savage Wars of Peace: Small Wars and the Rise of American Power. New York: Basic Books. Boswell, James. (1999) The Life of Samuel Johnson. London: Wordsworth. Bowden, Brett. (2009) The Empire of Civilization: The Evolution of an Imperial Idea. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Bronson, Rachel. (2002) When Soldiers Become Cops. Foreign Affairs 81 (6): 122132.

Mark Neocleous

157

Bush, George W. (2001) Address before a Joint Session of the Congress on the United States Response to the Terrorist Attacks of September 11, 20 September, Available at http://www. presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=64731&st=&st1=. (Accessed January 30, 2009.) Bush, George W. (2004) Commencement Address at the United States Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs, Colorado, June 2, Available at http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index. php?pid=72640&st=&st1=. (Accessed January 30, 2009.) Caffentzis, George C. (1995) On the Scottish Origins of Civilization. In Enduring Western Civilization: The Construction of the Concept of Western Civilization and Its Others, edited by Silvia Federici. Westport, CT: Praeger. Caygill, Howard. (2003) Perpetual Police: Kosovo and the Elision of Military Violence. European Journal of Social Theory 4 (1): 7380. Chesney, Robert, and Jack Goldsmith. (2008) Terrorism and the Convergence of Criminal and Military Detention Models. Stanford Law Review 60 (4): 10791133. Cheytz, Eric. (1993) Savage Law: The Plot Against American Indians. In Johnson and Grahams Lessee v. MIntosh and The Pioneers. In Cultures of United States Imperialism, edited by Amy Kaplan, and Donald E. Pease. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. Collingwood, Robin G. (1942) The New Leviathan, or Man, Society, Civilization and Barbarism. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Cordesman, Anthony H. (2003) The Lessons and Non-Lessons of the Air and Missile Campaign in Kosovo. Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies. Darwin, Charles. (2004) The Descent of Man. London: Penguin (Original work published in 1871). Day, Graham, and Christopher Freeman. (2003) Policekeeping Is the Key: Rebuilding the Internal Security Architecture of Postwar Iraq. International Affairs 79 (2): 299313. Dean, Mitchell. (1991) The Constitution of Poverty: Toward a Genealogy of Liberal Governance. London: Routledge. Dean, Mitchell. (1999) Governmentality. London: Sage. Dean, Mitchell. (2006) Military Intervention as Police Action? In The New Police Science: The Police Power in Domestic and International Governance, edited by Markus Dubber, and Mariana Valverde. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. Dean, Mitchell. (2010) Governmentality, 2nd edition. London: Sage. Department of Defense and Department of Justice. (1994) Memorandum of Understanding Between Department of Defense and Department of Justice on Operations Other than War and Law Enforcement. Washington, DC: Department of Defense and Department of Justice, 20 April, 1994. Donnelly, Jack. (1998) Human Rights: A New Standard of Civilization? International Affairs 74 (1): 124. Dubber, Markus. (2005) The Police Power: Patriarchy and the Foundations of American Government. New York: Columbia University Press. Elias, Nobert. (1978a) The Civilizing Process, Vol.1: The History of Manners. Translated by Edmund Jephcott. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. (Original work published in 1939.) Elias, Nobert. (1978b) The Civilizing Process, Vol. 2: State Formation and Civilization, translated by Edmund Jephcott. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. (Original work published in 1939.) Evans, Brad. (2010) Foucaults Legacy: Security, War and Violence in the 21st Century. Security Dialogue 41 (4): 413433. Febvre, Lucien. (1973) Civilisation: Evolution of a Word and a Group of Ideas. In A New Kind of History: From the Writings of Febvre, translated by K. Folca and edited by Peter Burke. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. (Original work published in 1930.) Federici, Silvia. (1995) The God That Never Failed: The Origins and Crises of Western Civilization. In Enduring Western Civilization: The Construction of the Concept of Western Civilization and Its Others, edited by Silvia Federici. Westport, CT: Praeger. Ferguson, Adam. (1792) Principles of Moral and Political Science, Vol.1. Edinburgh: W. Creech. Ferguson, Adam. (1966) An Essay on the History of Civil Society. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. (Original work published in 1767.) Fidler, David P. (2000) A Kindler, Gentler System of Capitulations? International Law, Structural Adjustment Policies, and the Standard of Liberal, Globalized Civilization. Texas International Law Journal 35 (3): 389413. Foucault, Michel. (2003) Society Must Be Defended: Lectures at the College de France, 19751976, translated by David Macey. London: Allen Lane. Giuliani, Rudolph. (2001) Address to the United Nations General Assembly, October 1, Available at http://www.nyc.gov/html/records/rwg/html/2001b/un_remarks.html. (Accessed January 30, 2009.)

158

The War on Terror as Civilizing Offensive

Gong, Gerrit W. (1984) The Standard of Civilization in International Society. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Gordon, Colin. (1991) Governmental Rationality: An Introduction. In The Foucault Effect: Studies in Governmentality, edited by Graham Burchell, Colin Gordon, and Peter Miller. Hemel Hempstead: Harvester Wheatsheaf. Gray, Colin S. (2009) Sheriff: Americas Defense of the New World Order. Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky Press. Guizot, M. (1863) Dictionnaire universel des synonymes de la langue francaise, sixieme edition. Paris: ` La Librairie Academique. Hardt, Michael, and Antonio Negri. (2000) Empire. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Hardt, Michael, and Antonio Negri. (2004) Multitude: War and Democracy in the Age of Empire. New York: Penguin. Hayek, Friedrich A. von. (1979) Law, Legislation and Liberty, Vol. 3. London: Routledge. Hills, Alice. (2004) Future War in Cities: Rethinking a Liberal Dilemma. London: Frank Cass. Hutchings, Kimberly. (1997) Foucault and International Relations Theory. In The Impact of Michel Foucault on the Social Sciences and Humanities, edited by Moya Lloyd, and Andrew Thacker. Houndmills: Macmillan. Ignatieff, Michael. (2003) Empire Lite: Nation-Building in Bosnia, Kosovo and Afghanistan. London: Vintage. Jabri, Vivienne. (2007) War and the Transformation of Global Politics. Houndmills: Palgrave. Knemeyer, Franz-Ludwig. (1980) Polizei. Economy and Society 9 (2): 173195. Koskenniemi, Martii. (2001) The Gentle Civilizer of Nations: The Rise and Fall of International Law 18701960. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Krieken, Robert van. (1990) The Organization of the Soul: Elias and Foucault on Discipline and the Self. Archives europeennes de sociologie 31 (2): 353371. Krieken, Robert van. (1999) The Barbarism of Civilization: Cultural Genocide and the Stolen Generations. British Journal of Sociology 50 (2): 297315. Lauterpacht, Hersh. (1947) Recognition in International Law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Llorent, Marina A. (2002) Civilization Versus Barbarism. In Collateral Language: A Users Guide to Americas New War, edited by John Collins, and Ross Glover. New York: New York University Press. Marx, Karl, and Frederick Engels. (1984) The Manifesto of the Communist Party. In Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, Vol. 6. London: Lawrence and Wishart (Original work published in 1848). Mehta, Uday Singh. (1999) Liberalism and Empire: A Study in Nineteenth-Century British Liberal Thought. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Meyer, Peter Alexander. (2008) Civic War and the Corruption of the Citizen. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Mill, John Stuart. (1977) On Civilization. London and Westminster Review. In The Collected Works of John Stuart Mill, Vol. XVIII, edited by J. M. Robson. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. (Original work published in 1836). Mill, John Stuart. (1984) A Few Words on Non-Intervention, Frasers Magazine. In The Collected Works of John Stuart Mill, Vol. XXI, edited by J. M. Robson. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. (Original work published in 1859). Minson, Jeffrey. (1985) Genealogies of Morals: Nietzsche, Foucault, Donzelot and the Eccentricity of Ethics. London: Macmillan. Mitzman, Arthur. (1987) The Civilizing Offensive: Mentalities, High Culture and Individual Psyches. Journal of Social History 20 (4): 663687. Mladek, Klaus. (2007) Exception Rules: Contemporary Political Theory and the Police. In Police Forces: A Cultural History of an Institution, edited by Klaus Mladek. Houndmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave. National Security Strategy of the United States of America. (2002) Washington, DC: Government Printing Ofce. Neocleous, Mark. (2000) The Fabrication of Social Order: A Critical Theory of Police Power. Pluto Press: London. Neocleous, Mark. (2010) War as Peace, Peace as Pacication. Radical Philosophy 159: 817. Oppenheim, Lassa. (1905) International Law: A Treatise, Vol.1: Peace. London: Longmans, Green and Co. Pagden, Anthony. (1988) The Defence of Civilization In Eighteenth-Century Social Theory. History of the Human Sciences 1 (1): 3345.

Mark Neocleous

159

Pasquino, Pasquale. (1991) Theatrum Politicum: The Genealogy of Capital Police and the State of Prosperity. In The Foucault Effect: Studies in Governmentality, edited by Graham Burchell, Colin Gordon, and Peter Miller. Hemel Hempstead: Harvester Wheatsheaf. Powell, Colin. (2001) Remarks to the Press, September 14. Available at http://avalon.law.yale.edu/ sept11/powell_brief05.asp. (Accessed January 30, 2009.) Rojas, Cristina. (2002) Civilization and Violence: Regimes of Representation in Nineteenth-Century Colombia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Salt, James, and M.L.R. Smith. (2008) Reconciling Policing and Military Objectives: Can Clausewitzian Theory Assist the Police Use of Force in the United Kingdom? Democracy and Security 4 (3): 221244. Salter, Mark B. (2002) Barbarians and Civilization in International Relations. London: Pluto Press. Schroder, Gerhard. (2001) Policy Statement by Chancellor Schroder, September 19, Available at http://usa.usembassy.de/gemeinsam/regerklschroe091901e.htm. (Accessed January 30, 2009.) Schwarzenberger, Georg. (1955) The Standard of Civilisation in International Law. Current Legal Problems 1955 (8): 212324. Schwarzenberger, Georg. (1976) A Manual of International Law, 6th edition. Abingdon, Oxon: Professional Books. Scott, James Brown. (1908) Texts of the Peace Conferences at The Hague, 1899 and 1907. Boston: Ginn and Co. Selby, Jan. (2007) Engaging Foucault: Discourse, Liberal Governance and the Limits of Foucauldian IR. International Relations 21 (3): 324345. Simon, Jonathon. (2007) Governing Through Crime. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Smith, Adam. (1979) An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund. (Original work published in 1776.) Smith, General Sir Rupert. (2001) The Utility of Force: The Art of War in the Modern World. London: Penguin. Starobinski, Jean. (1993) Blessings in Disguise; or, The Morality of Evil. Translated by Arthur Goldhammer. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Stephen, James Fitzjames. (1883) Foundations of the Government of India. Nineteenth Century 80: 541568. Stocking, George W. (1987) Victorian Anthropology. New York: The Free Press. The Invisible Committee. (2009) The Coming Insurrection. New York: Semiotext(e). Tribe, Keith. (1984) Cameralism and the Science of Government. The Journal of Modern History 56: 263284. Tucker, Robert W. (1977) The Inequality of Nations. London: Martin Robertson. US Army and Marine Corps. (2006) Counterinsurgency Field Manual. U.S. Army Field Manual No. 3-24 Marine Corps Warghting Publication No. 3-33.5. Verrips, Kitty. (1987) Noblemen, Farmers and Labourers: A Civilizing Offensive in a Dutch Village. Netherlands Journal of Sociology 23 (1): 316. Voltaire, F-M. A. (1965) The Philosophy of History. New York: Philosophical Library (Originally published in 1766). Walters, William. (2002) Deportation, Expulsion, and the International Police of Aliens. Citizenship Studies 6 (3): 265292. Weber, Cynthia. (1994) Simulating Sovereignty: Intervention, the State and Symbolic Exchange. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Williams, Raymond. (1976) Keywords. London: Fontana. Young, Robert J. C. (1995) Colonial Desire: Hybridity in Theory, Culture and Race. London: Routledge.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Group 6 - Cross-Cultural Contact With AmericansDocument49 pagesGroup 6 - Cross-Cultural Contact With AmericansLin NguyenNo ratings yet

- Digest Imbong V ComelecDocument2 pagesDigest Imbong V ComelecManila Loststudent100% (2)

- Attorney Bar Complaint FormDocument3 pagesAttorney Bar Complaint Formekschuller71730% (1)

- Amor Masovic Testimony To US CongressDocument5 pagesAmor Masovic Testimony To US CongressContributor BalkanchronicleNo ratings yet

- Who Is Playing Russian Roulette in SlovakiaDocument150 pagesWho Is Playing Russian Roulette in SlovakiaContributor BalkanchronicleNo ratings yet

- Serbias Sandzak Under MilosevicDocument22 pagesSerbias Sandzak Under MilosevicContributor BalkanchronicleNo ratings yet

- Soldier of Fortune (1993'02) 7PDocument7 pagesSoldier of Fortune (1993'02) 7PContributor BalkanchronicleNo ratings yet

- Black Muslims in AmericaDocument296 pagesBlack Muslims in AmericaContributor BalkanchronicleNo ratings yet

- Chetniks Encyclopedia of HolocaustDocument9 pagesChetniks Encyclopedia of HolocaustContributor BalkanchronicleNo ratings yet

- Reconstructing The Meaning of Being Montenegrin - by Jelena DzankicDocument25 pagesReconstructing The Meaning of Being Montenegrin - by Jelena DzankicContributor BalkanchronicleNo ratings yet

- Mladi Muslimani Interview Alija Izetbegovic TrhuljDocument8 pagesMladi Muslimani Interview Alija Izetbegovic TrhuljContributor BalkanchronicleNo ratings yet

- Community Education: To Reclaim and Transform What Has Been Made InvisibleDocument18 pagesCommunity Education: To Reclaim and Transform What Has Been Made InvisibleContributor BalkanchronicleNo ratings yet

- Tracking 2020census ResponseRate 04142020Document1 pageTracking 2020census ResponseRate 04142020Contributor BalkanchronicleNo ratings yet

- Pembroke Pines City Hall 601 City Center Way: FRIDAY, JULY 3, 2020Document2 pagesPembroke Pines City Hall 601 City Center Way: FRIDAY, JULY 3, 2020Contributor BalkanchronicleNo ratings yet

- Risk of Being Killed by Police Use of Force in The United States by Age, Race-Ethnicity, and SexDocument9 pagesRisk of Being Killed by Police Use of Force in The United States by Age, Race-Ethnicity, and SexContributor BalkanchronicleNo ratings yet

- Glasnik Islamske Zajednice 2010Document6 pagesGlasnik Islamske Zajednice 2010Contributor BalkanchronicleNo ratings yet

- Latinos and The Transformation of American ReligionDocument12 pagesLatinos and The Transformation of American ReligionContributor BalkanchronicleNo ratings yet

- BC Interview ENDERUN-The Bridge On The River DrinaDocument8 pagesBC Interview ENDERUN-The Bridge On The River DrinaContributor BalkanchronicleNo ratings yet

- Arab Muslim Attitudes Toward The West - Furia - LucasDocument22 pagesArab Muslim Attitudes Toward The West - Furia - LucasContributor BalkanchronicleNo ratings yet

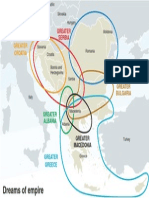

- Balkan Dreams of EmpiresDocument1 pageBalkan Dreams of EmpiresContributor BalkanchronicleNo ratings yet

- Inter-State River Water Disputes in India Is It Time For A New Mechanism Rather Than TribunalsDocument6 pagesInter-State River Water Disputes in India Is It Time For A New Mechanism Rather Than TribunalsNarendra GNo ratings yet

- Emile Armand Anarchist Individualism and Amorous ComradeshipDocument84 pagesEmile Armand Anarchist Individualism and Amorous ComradeshipRogerio Duarte Do Pateo Guarani KaiowáNo ratings yet

- Vidyanali Not Reg SchoolsDocument62 pagesVidyanali Not Reg SchoolssomunathayyaNo ratings yet

- Henry Sy, A Hero of Philippine CapitalismDocument1 pageHenry Sy, A Hero of Philippine CapitalismRea ManalangNo ratings yet

- Raus CSP22 FLT1QDocument19 pagesRaus CSP22 FLT1QPranav ChawlaNo ratings yet

- Gender and MediaDocument21 pagesGender and MediaDr. Nisanth.P.M100% (1)

- Monopolies and Restrictive Trade Practices Act 1969 MRTP Mechanism, Its Establishment, Features and FunctioningDocument37 pagesMonopolies and Restrictive Trade Practices Act 1969 MRTP Mechanism, Its Establishment, Features and FunctioningKamlesh MauryaNo ratings yet

- 柯 仪南; pinyin: Ke Yinan), a Chinese immigrant entrepreneur who sailed toDocument13 pages柯 仪南; pinyin: Ke Yinan), a Chinese immigrant entrepreneur who sailed toNothingNo ratings yet

- Decl HelsinkiDocument195 pagesDecl HelsinkiFernando GomesNo ratings yet

- Working in Groups Communication Principles and Strategies 7th EditionDocument25 pagesWorking in Groups Communication Principles and Strategies 7th EditionlunaNo ratings yet

- The Battle of BuxarDocument2 pagesThe Battle of Buxarhajrah978No ratings yet

- International Health Organizations and Nursing OrganizationsDocument35 pagesInternational Health Organizations and Nursing OrganizationsMuhammad SajjadNo ratings yet

- Global Governance: Rhea Mae Amit & Pamela PenaredondaDocument28 pagesGlobal Governance: Rhea Mae Amit & Pamela PenaredondaRhea Mae AmitNo ratings yet

- DD Form 4Document4 pagesDD Form 4Arthur BarieNo ratings yet

- DMG ShanghiDocument3 pagesDMG ShanghiMax Jerry Horowitz50% (2)

- Trends and IssuesDocument4 pagesTrends and IssuesJulieann OberesNo ratings yet

- Treasury FOIA Response 6-8-11Document60 pagesTreasury FOIA Response 6-8-11CREWNo ratings yet

- Wellesley News 3.11 PDFDocument12 pagesWellesley News 3.11 PDFRajesh VermaNo ratings yet

- Slavoj Zizek - A Permanent State of EmergencyDocument5 pagesSlavoj Zizek - A Permanent State of EmergencyknalltueteNo ratings yet

- Wickham. The Other Transition. From The Ancient World To FeudalismDocument34 pagesWickham. The Other Transition. From The Ancient World To FeudalismMariano SchlezNo ratings yet

- Davao Norte Police Provincial Office: Original SignedDocument4 pagesDavao Norte Police Provincial Office: Original SignedCarol JacintoNo ratings yet

- PAK UK RelationsDocument9 pagesPAK UK RelationsHussnain AsgharNo ratings yet

- Con Admin NotesDocument43 pagesCon Admin NotesAnnar e SistanumNo ratings yet

- AcceptableformslistDocument8 pagesAcceptableformslistNeeraj ChaudharyNo ratings yet

- TCWD 111 - Midterm ReviewerDocument10 pagesTCWD 111 - Midterm ReviewerGDHDFNo ratings yet

- SS 5 Aralin 1 PDFDocument26 pagesSS 5 Aralin 1 PDFChris Micah EugenioNo ratings yet

- Sample Certification LetterDocument3 pagesSample Certification LetterNgan TuyNo ratings yet