Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Governmental Accounting in Norway

Uploaded by

Yasser AzbarOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Governmental Accounting in Norway

Uploaded by

Yasser AzbarCopyright:

Available Formats

Financial Accountability & Management, 24(2), May 2008, 0267-4424

GOVERNMENTAL ACCOUNTING IN NORWAY: A DISCUSSION WITH IMPLICATIONS FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT

NORVALD MONSEN

INTRODUCTION

The development of governmental accounting is now receiving increasing attention around the world. This fact is evidenced in different ways, including conference publications based on papers presented at CIGAR-conferences as well as other publications having their origin in CIGAR activities (CIGAR = Comparative International Governmental Accounting Research) (see particularly Bac, 2001; Bourmistrov and Mellemvik, 2005; Buschor and Schedler, 1994; Caperchione and Mussari, 2000; Chan and Jones, 1988/1990; Chan et al., 1996a; Lande and Scheid, 2006; and Montesinos and Vela, 1995 and 2002). Moreover, a few years ago, researchers from the CIGAR network cooperated in carrying out an extensive study of the accounting and budgeting reforms of nine European countries (Finland, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom) and the European Commission. The study is presented in the book entitled Reforming Governmental Accounting and Budgeting in Europe, edited by Lder and Jones (2003a). The study reports: u

All of the countries covered by the study have embarked on reforms of the accounting and reporting systems for their core national or local governments towards full accrual accounting. Whereas all local government systems have been or are being reformed, in the national governments of Germany, Italy and the Netherlands the reform process has not yet started (Lder and Jones, 2003b, p. 19; emphasis added). u

In January 2007, the European Federation of Accountants (FEE The Fdration des Experts Comptables Europens; i.e., the representative orgae e e nization of the accountancy profession in Europe) published a study entitled Accrual Accounting in the Public Sector (FEE, 2007a). Here, a questionnaire was sent to European countries, receiving answers from 22 countries. In a press release based on this study (FEE, 2007b), it appears that European accountants support move to accrual accounting in the public sector. Furthermore, in order to acquire a more global view than the European evolution, it is of interest to focus on the development of international public sector (governmental) accounting standards

The author is from the Norwegian School of Economics and Business Administration (NHH: Norges Handelshyskole). He would like to thank two anonymous referees for their comments, which substantially contributed to improve the reasoning in the paper. Address for correspondence: Norvald Monsen, Norges Handelshyskole Helleveien 30, N-5045 Bergen, Norway. e-mail: norvald.monsen@nhh.no

2008 The Author Journal compilation C 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK and 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA.

C

(NHH),

151

152

MONSEN

(IPSASs), issued by the International Public Sector Accounting Standards Board (IPSASB). Although the IPSASB develops governmental accounting standards using both the accrual basis of accounting and the cash basis of accounting, it encourages use of the accrual basis. In a study presented by the IPSASB, it appears that 43 countries worldwide in 2006 to varying degrees have introduced, or are in the process of introducing, IPSASs, primarily based on the accrual basis of accounting (IPSASB, 2006). This indicates that the international development of governmental accounting consists of introducing accrual accounting. If we take a closer look at the CIGAR literature (see above for references), we will learn that the Contingency model of governmental accounting innovations, which has been developed by Professor Lder (Lder, 1992 and 1994), has u u been used as the dominating framework for analysing governmental accounting developments in many countries (see particularly Chan et al., 1996b; and Monsen and Nsi, 1998). Since this model aims at explaining the process of introducing a an accounting innovation, defined as accrual accounting, in governmental organizations, we can conclude that the majority of the CIGAR literature has studied governmental accounting developments, focusing on the introduction of accrual accounting. It is therefore also of interest to study a country, which has not introduced accrual accounting in the governmental sector. Since Norway is such a country, the purpose of this paper is to study the evolution of governmental accounting in this country, adding to our knowledge of governmental accounting developments around the world. Based on the Norwegian experiences, the paper aims to present some conclusions for the further development of international governmental accounting. Accounting developments can be studied at different levels, including the theoretical level (accounting theories), regulatory level (accounting laws, standards and recommendations) and practical level (accounting practice) (see e.g., Monsen and Wallace, 1995). In order to limit the discussion, the paper will focus on the first two levels, studying the influences of accounting theories (theoretical level) on the evolution of national and local governmental accounting regulations in Norway (regulatory level). The paper is structured as follows: the next section discusses accounting in its organizational context, followed by a comparison of commercial accounting and cameral accounting. Thereafter, governmental accounting in Norway, consisting of national governmental accounting and local governmental accounting, are presented and compared, before the paper ends with a discussion and some conclusions for the development of governmental accounting both in Norway and internationally.

ORGANIZATION AND ACCOUNTING

Accounting should be studied in its organizational context (see e.g., Hopwood, 1983; and Mellemvik et al., 1988). In this section, the relationship between

Journal compilation

C 2008 The Author 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

GOVERNMENTAL ACCOUNTING IN NORWAY

153

organization and accounting will therefore be discussed, first by focusing on the organizational context of business enterprises and governmental organizations, respectively, and thereafter by comparing business and governmental accounting, relating the discussion to their organizational contexts.

Business Enterprises vs Governmental Organizations

The interactions of a business enterprise (firm) with its environment is illustrated in Figure 1, showing the input-output process and the monetary process of the firm. The figure illustrates that a business enterprise interacts with three different markets. By selling products (and services) to its customers (product market), it receives financial resources. These resources can be used to pay for production factors (factor market), which the enterprise needs for producing its products. Furthermore, a business enterprise could also borrow money from banks and other financial institutions (capital market), and these borrowings must in turn be repaid in the form of loan instalments. The interactions of a governmental organization with its environment, however, are illustrated in Figure 2. It describes the input-output process, where production factors are converted into services (and products) and delivered to the receivers. This input-output process is to a large extent similar in the business and governmental contexts. The same is true with regard to transactions with financial (capital) markets. The monetary process of a governmental organization is, however, more complicated than the corresponding process of a business

Figure 1 The Capital Circulation Model of the Firm

THE INPOUT-OUTPUT PROCESS EXPENDITURES REVENUES

real input-output process

FA CTOR MARKET

production process cash monetary process PAYMENTS funds PAY MENTS repayments profit distribution

PRODUCT MARKET

CAPITAL MARKET

THE MONETARY PROCESS

Source: Nsi and Nsi (1997, Figure 1, p. 213). a a

C

2008 The Author Journal compilation

2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

154

MONSEN

Figure 2 The Economic Process Model of Government

ELECTORATE FINANCIAL MARKET Payments from debts and loans TAX PAY ERS

Politicians Planning and control PRODUCTION FACTOR MARKET Budget-accounts Money focus

THE MONETARY PROCESS payments fees cash input production process transfers output

product/service receivers

THE INPUT-OUTPUT PROCESS

Source: Monsen and Nsi (1998, Figure 3, p. 282). a

enterprise. Besides payments based on the input-output process transactions, i.e. payments for production factors and fees received for services (and products) delivered, taxes, state grants and other money transfers play an important role in the governmental monetary process.

Business Accounting vs Governmental Accounting

If we turn our attention to accounting, we will learn that the main accounting concepts are revenues and expenditures (see e.g., Mlhaupt, 1987). Revenues u are defined as claims on cash receipts, while expenditures are defined as obligations for cash payments. The revenues and expenditures will always have a financial (money/cash) effect, either in the form of immediate or later cash inflows and immediate or later cash outflows, respectively. When referring to an accounting model reporting only the immediate cash effect of the revenues and expenditures, the term financial (cash) accounts will be used. On the other hand, when the later cash effect of the revenues and expenditures, in the form of accounts receivable and liabilities, respectively, are reported in addition to the immediate cash effect, the term financial (money) accounts will be used. Furthermore, it may also be of interest to focus on the accrual effect of the revenues and expenditures, in the form of revenues earned or deferred and expenses incurred or deferred, respectively. When referring to

C 2008 The Author 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Journal compilation

GOVERNMENTAL ACCOUNTING IN NORWAY

155

such an accounting model, the term performance (accrual) accounts will be used. Basically, there are two main groups of bookkeeping methods to use in financial accounting, namely single-entry bookkeeping and double-entry bookkeeping. The former method refers to the procedure of entering one amount on one side of a particular account. The latter method, however, refers to the procedure of entering two similar amounts on the opposite sides of two different accounts (debit = credit). As reported by Lee (1986), originally single-entry bookkeeping of cash transactions was the bookkeeping method used in the business sector. Hence, business accounting could historically be characterized as representing financial (cash) accounts. Over time, however, single-entry bookkeeping was developed to systematic single-entry bookkeeping, allowing for reporting the performance (accrual) effect of the revenues and expenditures via the payment side (balance accounts) (see the lower part of Figure 1; also see Kosiol, 1967, for further details). Over the ages, however, bookkeeping in the business sector has developed further. In particular, the double-entry bookkeeping method emerged in response to the needs of businessmen in Italy in the thirteenth century (Kam, 1990, p. 29), and Luca Paciolis book Summa de Arithmetica Geometrica Proportioni et Proportionalita (Review of Arithmetic, Geometry and Proportions) in 1494 was the first book on double-entry bookkeeping to be published (see e.g., Kam, 1990, p. 19). This particular bookkeeping method will be revisited below. Since the governmental context (see Figure 2) has been different from the business context (see Figure 1), governmental accounting has historically been different from business accounting. In particular, since there are several money transfers (e.g., tax revenues and social security payments) without a service in return, managing and controlling the money transfers have been specifically important in governmental organizations. Therefore, traditional governmental accounting has focused on the money effect of the revenues and expenditures, either representing financial (cash) accounts or financial (money) accounts. Moreover, the comparison of accounting figures with financial (money/cash) budgetary figures has also determined the financial (money/cash) focus of traditional governmental accounting, separating it from the performance (accrual) focus of business accounting. For example, cameral accounting in its original version is such a traditional governmental accounting model, which was developed in the German speaking countries (Austria, Germany and Switzerland; see Buschor, 1994) from about 1500. Furthermore, Walb (1926) argues that the development of cameral accounting parallels that of business accounting, namely the development of a control instrument, the preparation of accounting information for statistical purposes and the preparation of profit and loss accounts, showing the performance (accrual) result (see Monsen, 2002, for an English summary of the historical development of cameral accounting). In the following section, the current versions of commercial (business) accounting and cameral (governmental) accounting will be presented and compared in more detail.

C

2008 The Author Journal compilation

2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

156

MONSEN COMMERCIAL ACCOUNTING VS CAMERAL ACCOUNTING

Today, accrual accounting is prepared in the business sector, using double-entry bookkeeping. This is a likely reason why the term accrual accounting is generally used, without any further specification. However, accrual accounting information can alternatively be prepared within cameral accounting, using systematic singleentry bookkeeping. In this paper, referring to accrual accounting prepared by using both double-entry bookkeeping and systematic single-entry bookkeeping, it is important to apply a more precise term than accrual accounting when referring to the accounting model prepared by using the former method. Inspired by Perrin (1984) and Chan (2003), the term commercial accrual accounting will therefore be used when referring to this particular accounting model. The merchants double-entry bookkeeping method represents the original and dominating variant of double-entry bookkeeping. In fact, this particular variant is generally referred to simply as double-entry bookkeeping or the double-entry bookkeeping method (see e.g., Kam, 1990). However, since other variants of double-entry bookkeeping will also be discussed in this paper, it is beneficial to add an adjective when referring to the particular double-entry bookkeeping method used in commercial accounting. Inspired by Walb (1926), I have chosen the adjective merchant (English translation of the German adjective kaufmnnisch), thus using the term the merchants double-entry bookkeeping a method. Furthermore, use of the merchants double-entry bookkeeping method allows for reporting the performance (accrual) result via both the payment side of the transactions (see the lower part of Figure 1) and the activity side of the transactions (see the upper part of Figure 1). This dual result presentation is made possible by adding profit and loss accounts (representing the activity side) to the balance accounts (representing the payment side) (Walb, 1926; and Kosiol, 1967). This duality implies that there is a direct link between the balance accounts and the profit and loss accounts. This direct link has always played an important role in continental European countries, as well as in the Nordic countries, which historically have been strongly influenced by continental Europe, particularly by Germany (see e.g., Monsen and Wallace, 1995). In the German literature one says that the profit and loss accounts and the balance accounts are prepared in verbundener Form (English translation: in a directly-linked way; see e.g., Wysocki, 1965, p. 43), and in Norway the term kongruensprinsippet (English translation: congruence principle; see e.g., Kinserdal, 1998, p. 315) is used for this direct link between the profit and loss accounts and the balance accounts. Furthermore, cash transactions without an effect on the performance result (e.g., receipt of new external loans) are reported on the debit and credit sides of the balance accounts only (and not in the profit and loss accounts), implying that the balance accounts report total assets, liabilities and equity as of the balance accounts date. Use of the merchants double-entry bookkeeping method allows reporting of the performance (accrual) result via both the payment side (cp. the net equity change

C 2008 The Author 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Journal compilation

GOVERNMENTAL ACCOUNTING IN NORWAY

157

as reported in the balance accounts) and the activity side (cp. revenues earned minus expenses incurred as reported in the profit and loss accounts) (Walb, 1926). Hence, the merchants double-entry bookkeeping method forms the basis of performance (accrual) accounts (see Figure 3; also see Monsen, 2006a). According to Walb (1926) it is precisely this dual and more informative presentation of the performance result (via both the payment and activity sides), which is the advantage of using the merchants double-entry bookkeeping method compared to using the merchants single-entry bookkeeping method, where the performance result is reported via the payment side only. Ijiri (1967) focuses on two other dimensions of the double-entry bookkeeping method instead of the dual performance result presentation (via both the payment and activity sides): the essence of double-entry is that every increment is causally related to a decrement, and the significant contribution of double-entry over single-entry is that the present financial status of a firm is fully accounted for by past events (Ijiri, 1982, p. 9). As of a given date, the assets and liabilities describe the present position of an enterprise, and the capital accounts, including income (i.e., the performance result), can be seen as a summary of past events. If past events have been properly accounted for, then the cumulative past should equal the present. In single-entry bookkeeping the present status is represented by a list of assets and liabilities, but double-entry compels an accounting of the present by an appropriate set of capital accounts that captures the past events that led to the present position. Thus, according to Kam (1990, p. 37), accountability is the essence of double-entry. If we turn our attention to cameral accounting, we will learn that today there exist two main groups, namely administrative cameralistics and enterprise

Figure 3 Cameral Accounting and Commercial Accounting

Single-entry bookkeeping

Systematic single-entry bookkeeping

Double-entry bookkeeping COMMERCIAL ACCOUNTING

CAMERAL ACCOUNTING The single-entry bookkeeping method of administrative cameralistics The systematic single-entry bookkeeping method of enterprise cameralistics

The merchants double-entry bookkeeping method

Financial (money) accounts

Modified financial (money) accounts/ performance (accrual) accounts

Performance (accrual) accounts

Source: Developed Version of Figure 1 (p. 362) and Figure 2 (p. 367) in Monsen (2006a).

C

2008 The Author Journal compilation

2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

158

MONSEN

cameralistics (Oettle, 1990; and Monsen, 2002). Administrative cameralistics were developed for use by the core part of a governmental organization, which is primarily financed by tax revenues (see Figure 2). The main objectives of this original version of cameral accounting are money management, budgetary control and payment control. In other words, administrative cameralistics should help to control that public (tax) revenues are managed (money management) within the boundaries of a politically adopted budget (budgetary control). Moreover, as pointed out above, there are many money transfers without a service in return in governmental organizations. Therefore, there is a general rule in the governmental sector saying that no cash can be received or paid by a person without receiving a previous or simultaneous payment instruction from another person having this competence. Administrative cameralistics is therefore also developed for fulfilling the objective of payment control. Administrative cameralistics use a developed version of single-entry bookkeeping, which can be referred to as the single-entry bookkeeping method of administrative cameralistics (Monsen, 2006a; see Figure 3). While the merchants single-entry bookkeeping method forms the basis of financial (cash) accounts, showing immediate cash inflows and outflows, the single-entry bookkeeping method of administrative cameralistics forms the basis of financial (money) accounts, showing total revenues and expenditures (i.e., immediate cash inflows and outflows as well as later cash inflows (accounts receivable) and later cash outflows (liabilities)). Over time, however, an increasing number of governmental organizations established their own enterprises (e.g., electricity companies), which were more similar to business enterprises (being market-financed; see Figure 1) than to the core governmental organization (being budget-financed; see Figure 2). As a result, a developed version of cameral accounting was worked out, with the objective of providing precisely the same type of information for the governmental enterprises as that which could have been prepared by using the merchants double-entry bookkeeping method, namely accrual accounting information. Enterprise cameralistics is the term used when referring to this particular version of cameral accounting. Enterprise cameralistics use a developed version of systematic single-entry bookkeeping, which can be referred to as the systematic single-entry bookkeeping method of enterprise cameralistics (Monsen, 2006a; see Figure 3). As distinct from the merchants systematic single-entry bookkeeping method, which allows the preparation of the performance result via the payment side only (see the lower part of Figure 1), use of the systematic single-entry bookkeeping method of enterprise cameralistics allows the preparation of the performance result via both the payment side (see the lower part of Figure 1) and the activity side (see the upper part of Figure 1). Hence, the performance (accrual) result is reported in precisely the same two informative ways as it is reported when using the merchants double-entry bookkeeping method, namely in the balance accounts (cp. the net equity change during the accounting year) and in the profit and loss accounts (as the difference between revenues earned and expenses incurred).

C 2008 The Author 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Journal compilation

GOVERNMENTAL ACCOUNTING IN NORWAY

159

The systematic single-entry bookkeeping method of enterprise cameralistics thus forms the basis of modified financial (money) accounts/performance (accrual) accounts (see Figure 3; also see Monsen, 2006a). The literature about cameral accounting is basically published in German (see particularly Walb, 1926; Johns, 1951; and Wysocki, 1965 and Mlhaupt, u 1987). In later years, however, some English language articles referring to German cameral accounting have been published (see particularly, Oettle, 1990; Monsen, 2001, 2002, 2006a and 2007). Therefore, non-German speaking readers interested in further derails about administrative and enterprise cameralistics, including numerical examples (see Monsen, 2002 and 2007), are referred to these English language references.

GOVERNMENTAL ACCOUNTING IN NORWAY

In Norway there are three levels of government, namely national, regional and municipal levels. Regarding the accounting (and budgeting) regulations, different regulations have been issued for the national government and for the local governments (i.e., the regional governments and the municipalities).

National Governmental Accounting

National governmental accounting (and budgeting) in Norway is rooted in the Constitution of 1814. Historically, when preparing the accounts of the Ministry of Finance and the other departments, single-entry bookkeeping of revenues and expenditures were carried out. However, in 1876 Statsrevisonen (STR Office of the Auditor General) prepared a document, arguing for the introduction of double-entry bookkeeping in national governmental accounting:

This characteristic, that bookkeeping according to the double-entry bookkeeping method is self- controllable, and that this bookkeeping thus gives a strong guarantee for the accuracy of the closed accounts, has an important significance, on which the utmost stress must be laid (STR1876; translated from Norwegian).

Based on this document, use of the principle of double-entry bookkeeping was introduced in national governmental accounting from 1879. Moreover, it was underlined that the national accounts should represent budgetary accounts, contributing to budgetary control, as well as cash accounts, contributing to payment control. In 1928, the Parliament adopted the bevilgningsreglement (appropriation guidelines), regulation how to prepare the budget and accounts of the national government. Later versions have largely prolonged the principles introduced in the first version of these guidelines (see Trlim et al., 1998, for a a historical review of the appropriation guidelines). The main principles specified in the appropriation guidelines are the principle of annuality (i.e., the budget and accounts should be prepared annually), the cash principle (i.e., bookkeeping of immediate cash inflows and outflows), the gross

C

2008 The Author Journal compilation

2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

160

MONSEN

principle (i.e., the cash inflows and outflows should be reported separately, even though they relate to the same activity) and the principle of comprehensiveness (i.e., one should incorporate all expected cash flows in the budget, thus reducing the need for later budget adjustments). It is of special interest to observe that the cash principle has always been a key principle in the appropriation guidelines. Even though this principle formally applies only to the accounts, there has never been any doubt that the budget should also be prepared using the cash principle (Trlin et al., 1998, p. 3). Gradually, however, some exceptions to the cash a principle have been introduced, implying that the appropriation guidelines today contain a modified cash principle. It can be observed that the objectives of Norwegian national governmental accounting are in accordance with the cameral financial objectives of money management, budgetary control and payment control (Monsen, 2005). However, unlike cameral accounting, which uses the principle of single-entry bookkeeping, the principle of double-entry bookkeeping has been used in national governmental accounting since 1879. In order to prepare financial (cash) accounts by using double-entry bookkeeping, this bookkeeping method cannot be used identically with the way the merchant uses it when preparing his performance (accrual) accounts, referred to as the merchants double-entry bookkeeping method. Hence, a special variant of double-entry bookkeeping, which can be referred to as the double-entry bookkeeping method of national governmental accounting in Norway has been developed (Monsen, 2006b; see Figure 4). Today, a pilot project is undertaken, attempting to introduce the merchants double-entry bookkeeping method in ten selected government departments, referred to as pilot units. The main motivation for these attempts is a desire for reporting better cost information in general as well as a wish to establish a better platform on which to base cost analyses of different activities. Another objective is

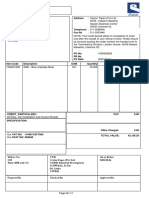

Figure 4 Governmental Accounting in Norway.

Double-entry bookkeeping GOVERNMENTAL ACCOUNTING IN NORWAY

The double-entry bookkeeping The double-entry bookkeeping method of national governmental method of local governmental accounting in Norway accounting in Norway

Financial (cash) accounts

Financial (money) accounts

Journal compilation

C 2008 The Author 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

GOVERNMENTAL ACCOUNTING IN NORWAY

161

to prepare a comprehensive overview of the assets and liabilities belonging to the national government (NOU 2003:06). It is of special interest to observe that the pilot project of introducing the merchants double-entry bookkeeping method for preparing accrual accounting information (i.e., performance (accrual accounts)) should not result in a new management procedure. The budgetary appropriations of the Parliament should continue to be based on the cash principle, and all government departments, including the pilot units, should still use the cash principle in their official accounts.

Local Governmental Accounting

As opposed to the few and general rules regulating national governmental accounting (and budgeting), which are stated in the appropriation guidelines, there are extensive and detailed rules regulating local governmental accounting (and budgeting). In fact, the first local governmental accounting regulation (Forskrift = F) was issued in 1883, and required the local governments to prepare financial (cash) accounts:

In the first Norwegian regulation (F1883), it seems as if the cameral accounting system has made a hit. The accounts according to this regulation represent, among other things, pure cash accounts (Mellemvik, 1987, p. 60; translated from Norwegian).

Thus, the first local governmental accounting regulation was strongly influenced by cameral accounting. In particular, the main objective of local governmental accounting (see F1936, p. 66) corresponds to the main objective of administrative cameralistics, namely controlling public (tax) money within the financial boundaries of a politically adopted budget. Therefore, since 1924 we find a strong link between budgeting and accounting within local governmental accounting. Moreover, it is of interest to observe that F1924 requires the bookkeeping of total revenues (i.e., immediate and later cash inflows) and total expenditures (i.e., immediate and later cash outflows), as opposed only to bookkeeping of immediate cash inflows and outflows, such as F1883 required. In Norwegian, this principle of entering revenues and expenditures on the accounts is referred to by the term anordningsprinsipp, having its origin in the term Anordnungsprinzip, which is used in the German cameral accounting terminology. Also, in 1924 the principle of double-entry bookkeeping was introduced in local governmental accounting (F1924). Moreover, the following subsequent regulations have been issued: F1941, F1942, F1957, F1971, F1990, F1993, FB2000, FR2000, MF2000. As pointed out above, several payments without a service in return are undertaken in governmental organizations. It is therefore especially important with payment control in these organizations, something which has resulted in the fact that the cameral account has been specifically developed for contributing to such control (Mlhaupt, 1987). Hence, the cameral account has separate u columns for payment instructions and actual payments. Even though Norway

C

2008 The Author Journal compilation

2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

162

MONSEN

has introduced the merchants double-sided account (with debit and credit sides without separate columns for payment instructions and actual payments), instead of using the cameral single-sided account (with such columns both on the revenue and expenditure sides), one wants to continue controlling that no cash is received or paid by a person, without first having received a payment instruction from another person, who has the authority to issue such a payment instruction (payment control). Therefore, F1942 requires the preparation of a payment instructions book in addition to the bookkeeping carried out by using the local governmental bookkeeping method (F1942, p. 165). In summary, the local governmental accounting regulations require the local governments to prepare financial (money) accounts, using anordningsprinsippet (i.e., bookkeeping of revenues and expenditures), having its origin in cameral accounting, and using the merchants accounts (with debit and credit sides), having its origin in commercial accounting. As a result of these requirements, the principle of double-entry bookkeeping cannot be used identically within local governmental accounting in Norway as it is used within commercial accrual accounting, which is based on the bookkeeping of revenues earned and expenses incurred as well as the congruence principle (i.e., there is a direct link between the balance accounts and the profit and loss accounts). Furthermore, neither can it be used identically with the way the principle of double-entry bookkeeping is used within national governmental accounting in Norway, where the focus is on immediate cash inflows and outflows. Hence, the double-entry bookkeeping method used within local governmental accounting in Norway represents a special variant of double-entry bookkeeping, which can be referred to as the double-entry bookkeeping method of local governmental accounting in Norway (see Figure 4; also see Monsen, 2006a).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

Internationally, an increasing number of countries have introduced, or are in the process of introducing, the merchants double-entry bookkeeping method in their governmental organizations in order to prepare accrual accounting information. This development is strongly related to another international trend, namely the introduction of New Public Management (NPM) in governmental organizations (see Hood, 1985). Olson et al. (1998b, p. 462) argue, however, that one should be careful with introducing corporate (accruals-based) accounting systems in public sector (governmental) organizations. Several other scholars have also questioned the usefulness of business-like accounting techniques in these organizations (e.g., Bromwich and Lapsley, 1997; Falkman, 1997; Brorstrm, 1998; Guthrie, 1998; o Robinson, 1998; and Monsen, 2002). Others have carried out empirical studies in public sector organizations in which accrual accounting has been introduced (e.g., ter Bogt and van Helden, 2000; Pallot, 2001; and Newberry and Pallot, 2004). Although the results of these studies vary, Paulson (2006, pp. 4748)

Journal compilation

C 2008 The Author 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

GOVERNMENTAL ACCOUNTING IN NORWAY

163

underlines that most of them lead to a questioning of the accrual accounting movement (i.e., commercial accrual accounting) in governmental organizations. Therefore, commercial accrual accounting should not be the only accounting theory used as a framework for developing governmental accounting internationally. It appears from the presentation of cameral accounting earlier in the paper, that this particular accounting theory has much to offer researchers and practitioners engaged in developing governmental accounting. Historically, cameral accounting in the form of administrative cameralistics was developed for the core part of a governmental organization, aiming at fulfilling the objectives of money management, budgetary control and payment control. And even though the international development towards the introduction of businesslike accounting techniques in the public (governmental) sector seems to have started in the latter 1970s and early 1980s (see Olson et al., 1998a, p. 17), studies of older German literature reveal that such attempts took place in the German speaking countries much earlier (see particularly, Walb, 1926; Johns, 1951; Wysocki, 1965; and also see Monsen, 2002, which presents a summary of this German development in English). In fact, these attempts failed every time, due to the different organizational contexts of business (commercial) and public sector (governmental) organizations (compare Figures 1 and 2), in which commercial and governmental accounting, respectively, were used. At the same time, however, a demand for accrual accounting information appeared in governmental enterprises, which were more similar to commercial enterprises, being marked-financed, than they were to the core governmental organization, being budget-financed. In order to satisfy this demand, a developed version of cameral accounting (enterprise cameralistics) was worked out with the purpose of preparing precisely the same type of information as the one prepared within commercial accounting, namely accrual accounting information. Here it should be underlined that enterprise cameralistics was added to administrative cameralistics, allowing the preparation of accrual accounting information (for governmental enterprises) as a supplement to the preparation of financial (money) information (for the core part of the governmental organization). This was thus a development deviating from the current international development, where the introduction of accrual accounting in the form of commercial accounting is replacing traditional governmental accounting in the form of financial (cash) accounts or financial (money) accounts. Given these German experiences, cameral accounting is offered for use in further developments of governmental accounting around the world, including Norway. It is true, however, that the current international governmental accounting context is different from the context of governmental accounting as it was earlier in Germany, something that may lead to more successful introductions of commercial accrual accounting in the public (governmental) sector. On the other hand, also today, money management, budgetary control and payment control (i.e., the cameral financial objectives) are important objectives of governmental accounting in many countries, including Norway, along with the objective of

C

2008 The Author Journal compilation

2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

164

MONSEN

providing cost information, contributing to performance management. And as it appears from the above presentation of cameral accounting, this particular accounting theory can provide information satisfying all of these objectives, if enterprise cameralistics (providing accrual accounting information) is added to administrative cameralistics (providing financial (money/cash) information). In conclusion, the ongoing international debate about governmental accounting should not consider commercial accrual accounting as the only alternative for use in governmental organizations; cameral accounting should also be considered. In particular, governmental accounting should be studied in its organizational context, focusing on the objectives of governmental accounting. Therefore, one should start discussing the objectives of governmental accounting and thereafter decide to develop a governmental accounting system within the framework of one particular accounting theory. By so doing, one would avoid the Norwegian situation with very peculiar and complicated governmental bookkeeping methods, precisely due to the attempts to combine cameral and commercial accounting thinking. In particular, if the main objectives will be similar to the cameral financial objectives of money management, budgetary control and payment control, administrative cameralistics should be considered for use. If one wants to add accrual accounting information to financial (money/cash) information, adding enterprise cameralistics to administrative cameralistics would be a good alternative. On the other hand, if the debate about the governmental accounting objectives ends with the argument that accrual accounting information should be of primary importance, although at the expense of financial (money/cash) information, one should consider to continue introducing commercial accrual accounting in the public (governmental) sector. In any case, further governmental accounting research is needed as a part of the ongoing debate about how to manage and control public money in public sector (governmental) organizations.

REFERENCES

Bac, A. (2001), International Comparative Issues in Government Accounting. The Similarities and Diffferences between Central Government Accounting and Local Government Accounting within or between Countries (Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht). Bogt, H.J. ter and G.J. van Helden (2000), Accounting Change in Dutch Government: Exploring the Gap Between Expectations and Realization, Management Accounting Research, Vol. 11, pp. 26379. Bourmistrov, A. and F. Mellemvik (2005), International Trends and Experiences in Government Accounting (Cappelen Akademisk Forlag, Oslo). Bromwich, M. and I. Lapsley (1997), Decentralisation and Management Accounting in Central Government: Recycling Old Ideas, Financial Accountability & Management, Vol. 13, No. 1, pp. 181201. Brorstrm, B. (1998), Accrual Accounting, Politics and Politicians, Financial Accountability & o Management, Vol. 14, No. 4, pp. 31933. Buschor, E. (1994), Introduction: From Advanced Public Accounting via Performance Measurement to New Public Management, in E. Buschor and K. Schedler (eds.), Perspectives on Performance Measurement and Public Sector Accounting (Paul Haupt Publishers, Berne/Stuttgart/Vienna).

C 2008 The Author 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Journal compilation

GOVERNMENTAL ACCOUNTING IN NORWAY

165

Buschor, E. and K. Schedler (eds.) (1994), Perspectives on Performance Measurement and Public Sector Accounting (Paul Haupt Publishers, Berne/Stuttgart/Vienna). Caperchione, E. and R. Mussari (2000), Comparative Issues in Local Government Accounting (Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht). Chan, J.L. (2003), Government Accounting: An Assessment of Theory, Purposes and Standards, Public Money and Management, Vol. 23, No. 1, pp. 1320. and R.H. Jones (1988/1990), Governmental Accounting and Auditing. International Comparisons (Routledge, London). and K.G. Lder (eds.) (1996a), Research in Governmental and Nonprofit Accounting (Jai u Press Inc., Greenwich/London). (1996b), Modeling Governmental Accounting Innovations: An Assessment and Future Research Directions, in J.L. Chan, R.H. Jones and K.G. Lder (eds.), Research in u Governmental and Nonprofit Accounting (Jai Press Inc., Greenwich/London). Falkman, P. (1997), Statlig redovisning enligt bokfringsmssiga grunder (Gteborg: CEFOS). o a o Fdration des Experts Comptables Europens (FEE) (2007a), Accrual Accounting in the Public e e e Sector (http://www.fee.be/publications/). (2007b), European Accountants Support Move to Accrual Accounting, Recognising Public Interest (Press release, 30.01.07) (http://www.fee.be/news/). Guthrie, J. (1998), Application of Accrual Accounting in the Australian Public Sector Rhetoric or Reality?, Financial Accountability & Management, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 119. Hopwood, A.G. (1983), On Trying to Study Accounting in the Context in which it Operates, Accounting, Organizations and Society, Vol. 8, pp. 287305. Hood, C. (1995), The New Public Managementin the 1980s: Variations on a Theme, Accounting, Organizations and Society, Vol. 20, No. 2/3, pp. 93109. Ijiri, Y. (1967), The Foundations of Accounting Measurement (Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.). (1982), Triple-Entry Bookkeeping and Income Momentum (SAR No. 18) (American Accounting Association, Sarasota, Fla). International Public Sector Accounting Standards Board (IPSASB) (2006), IPSAS Adoption by Governments (www.ifac.org/PublicSector/). Johns, R. (1951), Kameralistik. Grundlagen einer erwerbswirtschaftlichen Rechnung im Kameralstil (Betriebswirtschaftlicher Verlag Dr. Th. Gabeler, Wiesbaden). Kam, V. (1990), Accounting Theory (John Wiley & Sons, New York). Kinserdal, A. (1998), Finansregnskap med analyse. Del 1, 11. utgave (Cappelen Akademisk Forlag, Oslo). Kosiol, E. (1967), Buchhaltung und Bilanz (Walter de Gruyer & Co, Berlin). Lande, E. and J.-C. Scheid (eds.) (2006), Accounting Reform in the Public Sector: Mimicry, Fad or Necessity (Experts Comptables Media, Paris). Lee, T.A. (1986), Towards a Theory and Practice of Cash Flow Accounting (Garland Publishing, Inc., New York/London). Lder, K.G. (1992), A Contingency Model of Governmental Accounting Innovations in the u Political-Administrative Environment, Research in Governmental and Nonprofit Accounting, Vol. 7, pp. 99127. (1994), The Contingency ModelReconsidered: Experiences from Italy, Japan and Spain, in E. Buschor and K. Schedler (eds.), Perspectives on Performance Measurement and Public Sector Accounting (Paul Haupt Publishers, Berne/Stuttgart/Vienna). and R. Jones (eds.) (2003a), Reforming Governmental Accounting and Budgeting in Europe (Fachverlag Moderne Wirtschaft, Frankfurt am Main). (2003b), Chapter 1: The Diffusion of Accrual Accounting and Budgeting in European Governments A Cross Country Analysis, in K. Lder and R. Jones (eds.), Reforming u Governmental Accounting and Budgeting in Europe (Fachverlag Moderne Wirtschaft, Frankfurt am Main). Mellemvik, F. (1987), Behandling av ln i kommunale regnskaper (Universitetsforlaget, Oslo). a , N. Monsen and O. Olson (1988), Functions of Accounting A Discussion, Scandinavian Journal of Management, Vol. 4, No. 3/4, pp.10119. Monsen, N. (2001), Cameral Accounting and Cash Flow Reporting: Some Implications for Use of the Direct or Indirect Method, The European Accounting Review, Vol. 10, No. 4, pp. 70524. (2002), The Case for Cameral Accounting, Financial Accountability & Management, Vol. 18, No. 1, pp. 3972.

2008 The Author Journal compilation

2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

166

MONSEN

Monsen, N. (2005), Statsregnskapet i Norge br legges om, Magma, Vol. 8, No. 6, s. 6180. (2006a), Historical Development of Local Governmental Accounting in Norway, Financial Accountability & Management, Vol. 18, No. 1, pp. 35980. (2006b), Different Bookkeeping Methods: The Merchants Bookkeeping, The Cameralists Bookkeeping, The Bookkeeping of Norwegian Local Governmental Accounting, The Bookkeeping of Norwegian National Governmental Accounting (Kompendium, Norges Handelshyskole). (2007), Evolution of Cameral Accounting, Hallinnon Tutkimus (Administrative Studies), Vol. 26, No. 1, pp. 2233. and S. Nsi (1998), The Contingency Model of Governmental Accounting Innovations: A a Discussion, The European Accounting Review, Vol. 7, No. 2, pp. 27588. and W.A. Wallace (1995), Evolving Financial Reporting Practices: A Comparative Study of the Nordic Countries Harmonization Efforts, Contemporary Accounting Research, Vol. 11, No. 2, pp. 97397. Montesinos, V. and J.M. Vela (eds.) (1995), International Research in Public Sector Accounting, Reporting and Auditing (Instituto Valenciano de Investgiaciones Econmicas, S.A., Madrid). o (2002), Innovations in Governmental Accounting (Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht). Mlhaupt, L. (1987), Theorie und Praxis des ffentlichen Rechnungswesens in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland u o (Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden-Baden). Nsi, S. and J. Nsi (1997), Accounting and Business Economics Traditions in Finland From a a a Practical Discipline Into a Scientific Subject and Field of Research, The European Accounting Review, Vol. 6, No. 2, pp. 199229. Newberry, S. and J. Pallot (2004), Freedom From Coercion? NPM Incentives in New Zealand Central Government Departments, Management Accounting Research, Vol. 15, pp. 24766. Norges offentlige utredninger (2003), NOU 2003:06: Hva koster det? Bedre budsjettering og regnskapsfring i staten (Finansdepartementet, Oslo). Oettle, K. (1990), Cameralistics, in E. Grochla and E. Gaugler (eds.), Handbook of German Business Management (C.E. Poeschel Verlag, Stuttgart). Olson, O., J. Guthrie and C. Humphrey (1998a), International Experiences with New Public Financial Management (NPFM) Reforms: New World? Small World? Better World?, in O. Olson, J. Guthrie and C. Humphrey (eds.), Global Warning: Debating International Developments in New Public Financial Management (Cappelen Akademisk Forlag, Oslo). (1998b), Conclusion Growing Accustomed to Other Faces The Global Themes and Warnings of Our Project, in O. Olson, J. Guthrie and C. Humphrey (eds.), Global Warning: Debating International Developments in New Public Financial Management (Cappelen Akademisk Forlag, Oslo). Pallot, J. (2001), A Decade in Review: New Zealands Experience with Resource Accounting and Budgeting, Financial Accountability & Management, Vol. 17, No. 4, pp. 383400. Paulsson, G. (2006), Accrual Accounting in the Public Sector: Experiences from the Central Government in Sweden, Financial Accountability & Management, Vol. 22, No. 1, pp. 4762. Perrin, J. (1984), Accounting for Public Sector Assets, in A. Hopwood and C. Tomkins (eds.), Issues in Public Sector Accounting (Philip Allan Publishers Limited, Oxford). Robinson, M. (1998), Accrual Accounting and Efficiency of the Core Public Sector, Financial Accountability & Management, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 2137. Statsrevisionen (STR) (1876), Skrivelse fra Statsrevisionen angaaende Indfrelse av det dobbelte Bogholderi ved det offentlige regnskabsvsen Dokument nr. 70 fra Budgettkomiteen, Trlim, V., G. Axelsen and C. Meland (1998), Bevilgningsreglementet 70 ar. Historikk og a hovedprinsipper, arbeidsnotat nr. 2 (Finansdepartementet, Oslo). Walb, E. (1926), Die Erfolgsrechnung privater und ffentlicher Betriebe. Eine Grundlegung (Industriverlag o Spaeth & Linde, Berlin). Wysocki, K. (1965), Kameralistisches Rechnungswesen (C.E. Poeschel Verlag, Stuttgart). Local governmental budgeting and accounting regulations in Norway: Cirkulrefor Kommunekasseregnskaberne i Herredene og Byerne av 15. november 1883 (F1883). Forskrifter for budgettoppstilling og regnskapsavleggelse i bykommuner av 18. mars 1924 (F1924). Forskrifter for budsjett- og regnskapsordningen i rikets landkommuner (F1936). Rundskrivelse fra Innenriksdepartementet til fylkesmennene om budsjett og regnskap i rikets fylkeskommuner (F1941).

C 2008 The Author 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Journal compilation

GOVERNMENTAL ACCOUNTING IN NORWAY

Forskrifter for kommunale budsjett og regnskap (F1942). Forskrifter og veiledning for budsjettoppstilling og regnskapsfring i kommunene (F1957). Forskrifter og veiledning for budsjettoppstilling og regnskapsfring i kommunene (F1971). Nye forskrifter for kommunale og fylkeskommunale budsjetter og regnskaper (F1990). Nye forskrifter for kommunale og fylkeskommunale budsjetter og regnskaper (F1993). Forskrift om arsbudsjett (FB2000). Forskrift om arsregnskap og arsberetning (for kommuner og fylkeskommuner) (FR2000). Merknader til forskrift om arsregnskap og arsberetning (for kommuner og fylkeskommuner) (MF2000).

167

2008 The Author Journal compilation

2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Job Order Costing: Illustrative ProblemsDocument30 pagesJob Order Costing: Illustrative ProblemsPatrick LanceNo ratings yet

- Entrep 7 Business Implementation Autosaved Autosaved April 242020Document62 pagesEntrep 7 Business Implementation Autosaved Autosaved April 242020Carl Jayson Bravo-SierraNo ratings yet

- Accountancy Project Class 12 Cash Flow StatementDocument3 pagesAccountancy Project Class 12 Cash Flow StatementKasi Nath0% (5)

- CHAPTER - 2 - Exercise & ProblemsDocument6 pagesCHAPTER - 2 - Exercise & ProblemsFahad MushtaqNo ratings yet

- MAS Concept MapDocument1 pageMAS Concept MapCathlene TitoNo ratings yet

- Problem Solving: Merchandising Problem (Periodic Inventory System)Document1 pageProblem Solving: Merchandising Problem (Periodic Inventory System)Vincent Madrid100% (6)

- Presentation 1 OishiDocument22 pagesPresentation 1 Oishiglenn langcuyanNo ratings yet

- Depreciated Separately.: Property, Plant and EquipmentDocument5 pagesDepreciated Separately.: Property, Plant and EquipmentEmma Mariz GarciaNo ratings yet

- New Entity TPS THAYER CPAs in Great Houston AreaDocument2 pagesNew Entity TPS THAYER CPAs in Great Houston AreaPR.comNo ratings yet

- 02 FabmDocument28 pages02 FabmMavs MadriagaNo ratings yet

- Po22072001 PDFDocument1 pagePo22072001 PDFchanna abeygunawardanaNo ratings yet

- Fixed Assets PDFDocument21 pagesFixed Assets PDFSrihari GullaNo ratings yet

- EVALUACIÓN UNIDAD III InglesDocument2 pagesEVALUACIÓN UNIDAD III Inglesmaria lopezNo ratings yet

- 1st Pre-Board - MAS October 2011 BatchDocument8 pages1st Pre-Board - MAS October 2011 BatchKim Cristian MaañoNo ratings yet

- Advanced Financial Accounting - Paper 8 CPA PDFDocument10 pagesAdvanced Financial Accounting - Paper 8 CPA PDFAhmed Suleyman100% (1)

- BE AnalysisDocument5 pagesBE AnalysisFlorabelle May LibawanNo ratings yet

- EA and ReportingDocument17 pagesEA and ReportingsengottuvelNo ratings yet

- Paec Test PrepDocument4 pagesPaec Test Prepaliakhtar02100% (3)

- Acc ActivityDocument6 pagesAcc ActivityJoyce Eguia100% (1)

- ReceivablesDocument4 pagesReceivableshellohello50% (2)

- PA2 X ESP HW10 G1 Revanza TrivianDocument9 pagesPA2 X ESP HW10 G1 Revanza TrivianRevan KonglomeratNo ratings yet

- A. Balance Sheet: Hytek Income Statement Year 2012Document3 pagesA. Balance Sheet: Hytek Income Statement Year 2012marc chucuenNo ratings yet

- AP-5906 ReceivablesDocument5 pagesAP-5906 Receivablesjhouvan100% (1)

- CA Welcome Pack 2020 Reduced VersionDocument16 pagesCA Welcome Pack 2020 Reduced VersionHenry Sicelo NabelaNo ratings yet

- Recent Fabm ShortDocument20 pagesRecent Fabm Shortgk concepcionNo ratings yet

- Advanced Management AccountingDocument204 pagesAdvanced Management AccountingP TM100% (3)

- You Have Been Given The Following Information For Rpe ConsultingDocument1 pageYou Have Been Given The Following Information For Rpe ConsultingTaimour HassanNo ratings yet

- Audit Question EssayDocument204 pagesAudit Question EssayBts Kim Tae HyungNo ratings yet

- Mid Year AcqusitionDocument4 pagesMid Year AcqusitionOmolaja IbukunNo ratings yet

- Ifrs Viewpoint 3 Inventory Discounts and RebatesDocument8 pagesIfrs Viewpoint 3 Inventory Discounts and RebatesCollenNo ratings yet