Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Analysis of Major Characters

Uploaded by

Joelle ChewOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Analysis of Major Characters

Uploaded by

Joelle ChewCopyright:

Available Formats

Analysis of Major Characters

Babamukuru The central male presence in the novel, Babamukuru is a cold and enigmatic figure who is difficult to penetrate. While the books point of view is decidedly female, Babamukuru enacts the pressures and duties placed on men attempting to raise their families status and to shake off the specter of poverty. Babamukurus intelligence, ambition, and accomplishments are often taken for granted by others, as it is the others who reap the benefits of his hard work without attaining a full understanding of the sacrifices involved. His dual roles as parent and administrator are often at odds. He uses his job as headmaster to avoid any form of emotional intimacy with the women who share his home with him. His relationship with Nyasha is especially fraught, since her general conduct and academic performance at the mission school reflect his abilities not only as a father but also as a leader. From his earliest days, Babamukuru is the pawn of those who have offered him assistance and opportunity. He feels he has no choice but to accept the charity that the administrators at the mission school extend to him. After completing his education in South Africa, he does not want to pursue a higher degree in England, and he realizes that the hope of a brighter future for his extended family rests solely on his shoulders. Babamukuru stoically accepts his duty, even if he risks being viewed as a haughty authoritarian or unsympathetic bully by dictating what direction his family will take. He may not wish to be the leader, stern taskmaster, and voice of moral guidance in his family, but if he does not accept that role, his relatives will not be able to alter their circumstances on their own. Partly because of Babamukurus story and life experiences, Tambu realizes there are multiple interpretations to the choices that individuals make and the motives behind those choices.

Maiguru Maiguru is a complex, often contradictory, and multilayered character who grows increasingly concerned about the development of her children and their responses to the various cultural traditions, both Western and African, with which they have been raised. Her fears and anxieties are rooted in her own experience of trying to reconcile attitudes and behaviors that come from two very different worlds. Her conflicting attitudes suggest the deep divide that exists in her perception of herself as a woman and as an African. When the family returns to Rhodesia, Maiguru wishes her children to retain the mark of distinction and difference that they have achieved from living in a Western society. She defends the fact that they have lost their ability to communicate fluently in Shona, their native tongue. After the family has settled back into life in Rhodesia, Maigurus reactions and attitudes change, and she grows concerned at how Anglicized her children have become. Only when her daughter is severely ailing in the final stages of the novel does she realize the dire consequences of these conflicting cultural pressures that have been placed on her children.

When the family returns to the homestead for the holidays, Maiguru, highly educated and accustomed to earning her own living as an educator, is reduced to a traditional role as domestic drudge. During subsequent holidays, Maiguru refuses to attend the celebrations. Even more boldly, Maiguru confronts her husband about her lack of respect and recognition in the family, an action that leads to the even bolder move of her leaving the house altogether. Although she returns to the family fold, Maiguru has evolved into a realistic model of modern womanhood for the young girls in her care. She represents a subtle but emerging voice of feminist dissent, a woman ahead of her time who attempts to enact change in gradual and realizable ways.

Nyasha Highly intelligent, perceptive, and inquisitive, Nyasha is old beyond her years. Like the other female characters in Nervous Conditions, she is complex and multifaceted, and her dual nature reflects her status as the product of two worlds, Africa and England. On one hand she is emotional, passionate, and provocative, while on the other she is rational and profound in her thinking. Nyasha is admired by Tambu for her ability to see conflict and disagreement not as threats but as opportunities to increase her understanding of herself and the world. She uses the various experiences life presents her with as a chance to grow, learn, and improve. Initially, she thrives in her state of unresolved and often warring emotions and feelings, and she sees any inconsistencies in her feelings or her world as opportunities for greater self-development. Nyashas precocious nature and volatile, ungrounded identity eventually take their toll, and isolation and loneliness are her reward for being unconventional and fiercely independent. She is unpopular at the mission school, but this unpopularity is due more to her willfulness than the fact she is the headmasters daughter. Her inner resources and resolve are highly developed, but they can sustain her only so far. Over the course of the novel, the elements that define her and the aspects of her personality she most cherishes become the source of her unrest and ultimate breakdown. Nyasha begins to resent her outspoken nature and the constant spirit of resistance she displays, particularly to her father. The transformation leads to self-hatred, a dangerously negative body image that results in an eating disorder, and mental illness. Nyasha becomes a symbolic victim of the pressures to embrace modernity, change, enlightenment, and self-improvement.

Tambu Throughout Nervous Conditions, the adult Tambu looks back on her adolescence and her struggle to emerge into adulthood and formulate the foundation on which her adult life would be built. There are essentially two Tambus in the novel, and the narrator Tambu successfully generates tension between them. Tambu is a crafty and feisty narrator. She explores her own conflicted perceptions not only as a teenager but as an adult reexamining those years, a dual perspective that gives the novel richness and complexity. Tambu introduces herself to the reader harshly, proclaiming the fact that she is not upset

that her brother has died. As the presiding voice in the novel, she can manipulate how she is represented and perceived, but under the tough exterior is a hardworking girl who is eager to please and eager to advance herself. Her self-portrayal, with its unflattering as well as praiseworthy elements, represents the adult Tambus effort to convey the challenges faced by impoverished yet talented women in central Africa in the 1970s. A figure of those tumultuous and ever-changing times, Tambu emerges not as a flat and one-dimensional symbol but ultimately as a fallible and triumphant human presence.

You might also like

- Nervous Conditions Character EssayDocument2 pagesNervous Conditions Character EssayTim Butram100% (1)

- Nervous Condition EssayDocument3 pagesNervous Condition EssayBhavani PillayNo ratings yet

- Gender roles and colonial impacts in Nervous ConditionsDocument6 pagesGender roles and colonial impacts in Nervous ConditionsMaddalenaMissagliaNo ratings yet

- Socio-Cultural Explorations in Shashi Deshpande's "The Dark Holds No Terror"Document7 pagesSocio-Cultural Explorations in Shashi Deshpande's "The Dark Holds No Terror"Anonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- Comparing Themes in Malaysian Short Stories from Different ErasDocument7 pagesComparing Themes in Malaysian Short Stories from Different ErasFirdaus IsmailNo ratings yet

- Horse Meets Dog, by Elliot Kalan and Tim Miller, Is A Book About A Horse That Meets A Dog ForDocument14 pagesHorse Meets Dog, by Elliot Kalan and Tim Miller, Is A Book About A Horse That Meets A Dog Forapi-559432931No ratings yet

- Educated BookDocument5 pagesEducated BookМарія СінькевичNo ratings yet

- Holmesk2007 1Document62 pagesHolmesk2007 1Taitus silandaNo ratings yet

- NewDocument16 pagesNewBhareth Kumaran JNo ratings yet

- Joys of Motherhood: Theme of Motherhood in Buchi Emecheta's TheDocument4 pagesJoys of Motherhood: Theme of Motherhood in Buchi Emecheta's TheSONANo ratings yet

- Nervous-Conditions SummaryDocument2 pagesNervous-Conditions SummaryMayraniel RuizolNo ratings yet

- 1201 1422516262 PDFDocument7 pages1201 1422516262 PDFDipankar SarkarNo ratings yet

- So Long A LetterDocument2 pagesSo Long A LetterSusan Thomas100% (1)

- Pakistani Lit Story AnalysisDocument6 pagesPakistani Lit Story AnalysisSumaira IbrarNo ratings yet

- Week 1 DiscussionDocument2 pagesWeek 1 Discussionapi-572255929No ratings yet

- Nervous Conditions ThesisDocument6 pagesNervous Conditions ThesisJennifer Daniel100% (2)

- Timed WritingDocument2 pagesTimed Writingapi-321714250No ratings yet

- Anne Fine’s Work Explores Important Themes for Young PeopleDocument8 pagesAnne Fine’s Work Explores Important Themes for Young PeopleChong Beng LimNo ratings yet

- Poverty, Sexism and Family Strife in Sade Adeniran's NovelDocument12 pagesPoverty, Sexism and Family Strife in Sade Adeniran's NovelIfeoluwa WatsonNo ratings yet

- HUM 205 Final ESSAY - EditedDocument4 pagesHUM 205 Final ESSAY - EditedDan BorsNo ratings yet

- Eng2603 - Assignment 1Document7 pagesEng2603 - Assignment 1Kiana Reed100% (1)

- The Hardships o-WPS OfficeDocument1 pageThe Hardships o-WPS Officelucienakati55No ratings yet

- Mabuti Is GoodDocument2 pagesMabuti Is GoodAnonymous StrangerNo ratings yet

- Eng1501 Ass 2Document3 pagesEng1501 Ass 2Ntsako OraciaNo ratings yet

- Altering Trends in Indian Women in Jhumpa Lahiri's Novel The LowlandDocument6 pagesAltering Trends in Indian Women in Jhumpa Lahiri's Novel The LowlandEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Little Women Reflection PaperDocument2 pagesLittle Women Reflection PaperElaine Cunanan Madula100% (3)

- Week 5 DiscussionDocument2 pagesWeek 5 Discussionapi-572255929No ratings yet

- Essay 1 pcg-2Document7 pagesEssay 1 pcg-2api-666253970No ratings yet

- KKDocument15 pagesKKFanstaNo ratings yet

- Finaldraft ShelfessayDocument6 pagesFinaldraft Shelfessayapi-531497681No ratings yet

- Edu 201 SandersjonaheducatedDocument3 pagesEdu 201 Sandersjonaheducatedapi-735955672No ratings yet

- Critique Paper TineDocument6 pagesCritique Paper Tinekristine molenillaNo ratings yet

- The Lesson Bambara Thesis StatementDocument8 pagesThe Lesson Bambara Thesis Statementstacyjohnsonreno100% (2)

- Essay 2 FDDocument6 pagesEssay 2 FDConnor France100% (1)

- The Effects of Assimilation: This WayDocument4 pagesThe Effects of Assimilation: This WayDenise Deenicee MunjeriNo ratings yet

- Fasting, Feasting by Antia Desai, Houghton Mifflin CompanyDocument10 pagesFasting, Feasting by Antia Desai, Houghton Mifflin CompanyGLOBAL INFO-TECH KUMBAKONAMNo ratings yet

- Daniel PHD SynopsisDocument6 pagesDaniel PHD SynopsisdanielrubarajNo ratings yet

- The Breadwinner (2000) by Deborah EllisDocument7 pagesThe Breadwinner (2000) by Deborah EllisGrace DinayaNo ratings yet

- The Tale of GenjiDocument6 pagesThe Tale of GenjiKatherine HidalgoNo ratings yet

- Task 1Document7 pagesTask 1TRISHA COLEEN ASOTIGUENo ratings yet

- The School For Good and EvilDocument5 pagesThe School For Good and EvilrupertomagdiwangNo ratings yet

- About Kavery NambisanDocument4 pagesAbout Kavery Nambisanfreelancer8000% (1)

- Comparing Genres in Children's LiteratureDocument5 pagesComparing Genres in Children's LiteratureEllaine DaprosaNo ratings yet

- Definition Essay On LoveDocument3 pagesDefinition Essay On Lovelwfdwwwhd100% (2)

- Charakterisierung Jean, Sharron, Mrs. Tibbetts 11.10.2020 EnglischDocument1 pageCharakterisierung Jean, Sharron, Mrs. Tibbetts 11.10.2020 EnglischFDNo ratings yet

- Nervous Conditions: A Critique of The Colonial Education SystemDocument6 pagesNervous Conditions: A Critique of The Colonial Education SystemreveoNo ratings yet

- Article of Iqra RafiqueDocument8 pagesArticle of Iqra RafiqueFaisal JahangeerNo ratings yet

- Gender Discrimination and Suffering in Fasting, FeastingDocument5 pagesGender Discrimination and Suffering in Fasting, FeastingNynuNo ratings yet

- Chapter PageDocument49 pagesChapter PageKritidyuti PatraNo ratings yet

- Outside Rules Is A Compilation of Short Stories About Nonconformist YouthDocument4 pagesOutside Rules Is A Compilation of Short Stories About Nonconformist Youthapi-410624346No ratings yet

- Crag, Journal Manager, GAGPReview FINALDocument2 pagesCrag, Journal Manager, GAGPReview FINALTabhita TivaNo ratings yet

- Study Work Guide: Finders Keepers Grade 10 First Additional Language: Grade 10 First Additional LanguageFrom EverandStudy Work Guide: Finders Keepers Grade 10 First Additional Language: Grade 10 First Additional LanguageRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- The Joy Luck Club Literary CriticismDocument3 pagesThe Joy Luck Club Literary Criticismapi-269570988No ratings yet

- WOMEN'S Political RoleDocument3 pagesWOMEN'S Political Roleoej.ja97No ratings yet

- Week 5 DiscussionDocument3 pagesWeek 5 Discussionapi-528651903No ratings yet

- New Format Quinta Guia 6o.Document6 pagesNew Format Quinta Guia 6o.Enrique Vasquez MercadoNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting English Vocabulary of SLMCS StudentsDocument89 pagesFactors Affecting English Vocabulary of SLMCS StudentsSamantha Realuyo100% (1)

- Sex & God - How Religion Distorts Sexuality by Darrel W. RayDocument241 pagesSex & God - How Religion Distorts Sexuality by Darrel W. RayNg Zi Xiang100% (3)

- spd-590 Clinical Practice Evaluation 3Document12 pagesspd-590 Clinical Practice Evaluation 3api-501695666No ratings yet

- World Friends Korea, Ms. Jeehyun Yoon, KOICADocument26 pagesWorld Friends Korea, Ms. Jeehyun Yoon, KOICAforum-idsNo ratings yet

- Ba History Hons & Ba Prog History-3rd SemDocument73 pagesBa History Hons & Ba Prog History-3rd SemBasundhara ThakurNo ratings yet

- The Superior Social Skills of BilingualsDocument2 pagesThe Superior Social Skills of BilingualsPrasangi KodithuwakkuNo ratings yet

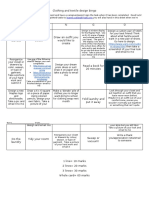

- Clothing and Textile Design BingoDocument2 pagesClothing and Textile Design Bingoapi-269296190No ratings yet

- reviewer ノಠ益ಠノ彡Document25 pagesreviewer ノಠ益ಠノ彡t4 we5 werg 5No ratings yet

- Quiz 1 Assessment 2Document2 pagesQuiz 1 Assessment 2Cedrick AbadNo ratings yet

- El Narrador en La Ciudad Dentro de La Temática de Los Cuentos deDocument163 pagesEl Narrador en La Ciudad Dentro de La Temática de Los Cuentos deSimone Schiavinato100% (1)

- Practical ResearchDocument2 pagesPractical ResearchFlora SedoroNo ratings yet

- Lord of The Flies Is William Golding's Most Famous Work. Published in 1954, The Book Tells TheDocument8 pagesLord of The Flies Is William Golding's Most Famous Work. Published in 1954, The Book Tells TheTamta GulordavaNo ratings yet

- Creative Nonfiction Q1 M5Document17 pagesCreative Nonfiction Q1 M5Pril Gueta87% (15)

- Literary Traditions and Conventions in the Dasam GranthDocument6 pagesLiterary Traditions and Conventions in the Dasam GranthJaswinderpal Singh LohaNo ratings yet

- Readings in Philippine History-Chapter 5-LemanaDocument56 pagesReadings in Philippine History-Chapter 5-LemanaKenneth DraperNo ratings yet

- Administration and SupervisionDocument14 pagesAdministration and Supervisionclarriza calalesNo ratings yet

- Your Personal Branding Strategy in 10 StepsDocument2 pagesYour Personal Branding Strategy in 10 StepsDoddy IsmunandarNo ratings yet

- Family: "A Group of People Who Are Related To Each Other, Such As A Mother, A Father, and Their Children"Document2 pagesFamily: "A Group of People Who Are Related To Each Other, Such As A Mother, A Father, and Their Children"Lucy Cristina ChauNo ratings yet

- Protective Factors SurveyDocument4 pagesProtective Factors SurveydcdiehlNo ratings yet

- Critical Book Review of "The Storm BoyDocument10 pagesCritical Book Review of "The Storm BoyGomgom SitungkirNo ratings yet

- Activity Design Sports ProgramDocument4 pagesActivity Design Sports ProgramTrisHa TreXie TraCy100% (2)

- Honest and Dishonesty Through Handwriting AnalysisDocument4 pagesHonest and Dishonesty Through Handwriting AnalysisRimple SanchlaNo ratings yet

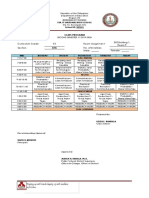

- SHS Schedule (Second Semester)Document24 pagesSHS Schedule (Second Semester)Aziladna SircNo ratings yet

- The Disciples of Christ Congo Mission in the 1930sDocument20 pagesThe Disciples of Christ Congo Mission in the 1930sHervé DisadidiNo ratings yet

- Pliant Like The BambooDocument3 pagesPliant Like The BambooAngelica Dyan MendozaNo ratings yet

- Tan Patricia Marie CVDocument2 pagesTan Patricia Marie CVGarry Sy EstradaNo ratings yet

- Masud Vai C.V Final 2Document2 pagesMasud Vai C.V Final 2Faruque SathiNo ratings yet

- Be Yourself, But CarefullDocument14 pagesBe Yourself, But Carefullmegha maheshwari50% (4)

- Peaceful Retreat: Designing a Vipassana Meditation Center in Mount AbuDocument14 pagesPeaceful Retreat: Designing a Vipassana Meditation Center in Mount AbuAnonymous Hq7gnMx7No ratings yet