Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Challenging The Hegemony of Eurocentric Psychology

Uploaded by

Darryl Laurenne SantosOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Challenging The Hegemony of Eurocentric Psychology

Uploaded by

Darryl Laurenne SantosCopyright:

Available Formats

Naidoo/Hegemony/1994

CHALLENGING THE HEGEMONY OF EUROCENTRIC PSYCHOLOGY

ANTHONY VERNON NAIDOO CENTRE FOR STUDENT COUNSELLING UNIVERSITY OF THE WESTERN CAPE

1996

Adapted from a paper presented at the Psychology and Societal Transformation Conference, University of the Western Cape, Bellville, South Africa.

Please reference as:

Naidoo, A.V. (1996). Challenging the hegemony of Eurocentric psychology. Journal of Community and Health Sciences, 2(2), 9-16.

Challenging the Hegemony of Eurocentric Psychology Introduction The title of this historical conference, Psychology and Societal Tranformation, poses two important interrelated questions as we face the rigours of transformation in all facets of our society. Firstly, why the need to transform psychology? Secondly, how can we begin to make psychology relevant to the sociopolitical context in South Africa? This paper examines these two crucial questions. In exploring these two questions I will be developing two central propositions: 1) Psychology has traditionally been Eurocentric; i.e, it derives from a White middle-class value system ( Katz, 1985; Smith, 1981). As a result mainstream psychology has largely been ethnocentric in its orientation, training and application and has neglected the mental health concerns of other racial groups and the socio-political injustices they endure on a daily basis. 2) Given this dereliction and disregard by the human service professions in addressing the mental health concerns and needs of other racial groups (Akbar, 1989; Sue, 1981), there is a compelling need to develop different paradigms and models to represent reality from the vantage point of the oppressed. This has echoed in the literature as a call to contextualise and indigenise psychology. During the past decade, a renewed interest and activism for a psychology with an Afrocentric paradigm has began to emerge more vigorously to contest the eurocentric substrate of psychology and benign pretensions of universality (Bulhan, 1985; Myers, 1988; White & Parham, 1990). In addition to developing these two propositions I would also like to consider some general suggestions of how to begin to effectively challenge and transform Eurocentric psychology. Definitions Three important concepts that need defining are hegemony, ethnocentrism, and Eurocentrism. Webster's dictionary defines hegemony as leadership or political

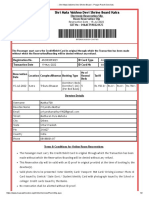

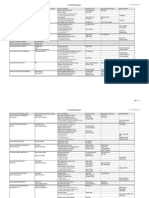

domination. Ethnocentrism refers to the dominating power and control of the cultural patterns, behaviours and attendant values of one particular ethnic or racial group. When the proclivity is to perceive, construct, and understand phenomena such as reality, behaviour, and theory for instance from a predominantly EuroAmerican or white cultural perspective, this form of ethnocentrism is called eurocentrism. As South Africans, we have all suffered the effects of eurocentrism in its more overt expression as apartheid. Why transform psychology? Mainstream psychological theory and practice has been criticised for being culturally encapsulated and lacking in cross-cultural relevance (Sue, 1981; Wrenn, 1962). It has been charged that "counselling approaches have been developed by and for the White, middle class person" (Atkinson, 1979, p.13). Counselling and psychotherapy have traditionally been conceptualised in Western, individualistic terms. Moreover, psychologists who use theory and training based on this monocultural perspective, often operate from the assumption that such a theory base can be applied to all populations. This has been referred to as the myth of sameness or the assumption of universality. Making psychology more responsive to the needs of culturally different populations requires a willingness to engage in examining the underlying cultural values that constitute the basis of the discipline (Wrenn, 1962). Literature has alluded to this in the past but has not made the comparison explicit or transparent. Despite pretensions at being morally, politically and ethically neutral, psychology is fundamentally Eurocentric, both in theory and practice. Making explicit the underlying dimensions of eurocentric psychology Katz (1985) asserts that White culture serves as the foundation for counselling theory, research and practice. By definition, white culture is the synthesis of ideas, values, norms, beliefs, and behaviours coalesced from descendants of White European ethnic groups. In Table 1 Katz identifies the major components of white culture making explicit its specific values and beliefs. In Table 2 a framework for

viewing the cultural dimensions of traditional counselling is presented. In juxtaposing the two tables, the similarities between White culture and the cultural values that form the foundations of traditional counselling theory and practice are not coincidental. Because counselling theory and practice developed out of the experience of White therapists and researchers working almost exclusively with White client systems, it comes as no startling revelation that the profession inherently reflects white cultural values. However, when these same behaviour and practices we call therapy are applied to members of other cultural groups, they may in fact represent values that are antagonistic to that culture and as such may unwittingly become tools of cultural oppression (Trimble & LaFromboise, 1987). --------------------------------------Insert table 1 & 2 about here ---------------------------------------

Bulhan (1985) influenced by the writings of Fanon (1959, 1963, 1967) exposes the deliberate and self-serving ethnocentric preoccupations of what he calls dominant psychology. He posits that dominant psychology is derived, founded, and imbued with the outlook that (a) the Euro-American world view is the only or best world view; (b) positivism or neo-positivism is the only or best approach to the conduct of scientific inquiry; and (c) the experience of white middle-class males are the only or most valid experiences in the world. He reminds the reader, however, that all psychological research and theorising entail some basic assumptions about the world and human nature. While these assumptions are implicit and often elusive, in their global assertions they are categorical and hardly permit exceptions. These basic assumptions or shared exemplars are neither empirically derived nor open to scientific inquiry, but they nevertheless pervade our perceptions of the world and how we theorise about it.

It so happens that the basic assumption of the dominant psychology is rarely examined or admitted. The reluctance to examine the basic assumptions of dominant psychology derives in part from fears of undermining the discipline's tenuous claims of its status as a science. That this dominant psychology is founded on and permeated with the implicit assumption that the only human reality is first Eurocentric, then middle class, and finally male in substance, represents a disregard that this culture-, class-, and sex-bound perspective is but one in a universe of diverse human realities (Baldwin, 1989; Bulhan, 1985; Katz, 1985; Sue, 1981). The perpetuation of this theory and practice predicated on one world view, one set of assumptions concerning human behaviour, and one set of values concerning mental health restricts our knowledge and understanding, limits our ability to be effective cross-culturally, and reduces the counselling process to a technicist-orientation (Kriegler, 1985). It also deprecates the value and usefulness of indigenous modes of intervening. Research methodology: Tools of enslavement or liberation The knowledge production component of dominant psychology has also been highlighted by several writers (Barnes, 1972; Bulhan, 1985; Guthrie, 1970; Williams, 1972) as being instrumental in rationalising and justifying the status quo and its attendant consequences such as racism and oppression. Bulhan (1985) charges that Eurocentric psychology's overidentification with the natural sciences fosters two reductionisms. The first is reductionism of human behaviour to individual psychology for the purpose of meaningful quantification. The second is the all-toofamiliar practice of reducing human psychology to its lower animal denominator. People thus come to be considered as if they were rats and experimental rats as if they were human. And, since some humans are considered more animal-like than others, who but people of colour, especially "primitive tribes" muses Bulhan (1985), can provide simpler analogues of the complex psychology of Whites. An analysis of studies about the behaviour of Blacks also reflects a bias toward a predominantly pathogenic focus (Guthrie, 1970). Historically, three models have

been used to guide and conceptualise research on non-white people in general and Blacks in particular (Sue, Arredondo, and McDavis, 1992). These models include: 1. The inferiority model. 2. The genetic deficiency model 3. The culturally deprived (deficient) model The inferiority model contended that Black people were lower on the evolutionary hierarchy than were Whites, were more primitive and, thus were more inherently pathological. The second model argued that Blacks and other racial and ethnic groups were genetically deficient. The differences between Whites and Blacks were reflections of biological and genetic inferiority. Several prominent South African psychologists (e.g., M.L. Fick and H Verwoerd) were unabashed proponents of the genetic inferiority hypothesis. The cultural deprivation model developed as well-intentioned attempts to negate the genetic deficiency model. This model argued that environmental rather than hereditary factors were responsible for the presumed deficiencies in Black behaviour. From this deficit model came the cultural deprivation hypothesis which presumed that, due to the inadequate exposure to the right culture (i.e., eurocentric values, norms, customs and lifestyles), Blacks were indeed culturally deprived or disadvantaged and required cultural enrichment. Implicit in the concept of cultural deprivation is the notion that the dominant White middle-class culture establishes and sets the normative standard. Thus any behaviours, values, and lifestyles that differed from the Euro-American norm were seen as deficient and even deviant. These models have served to perpetuate a view that the culturally different are inherently pathological and have also undergirded racist research and counselling practices (Sue, Arredondo, & McDavis, 1992) The advent of the multicultural model has been stimulated by the proposition that behaviours, life styles, languages, values, etc., can only be evaluated within the context of a specific cultural milieu (Pedersen, 1987; White, 1972). This model assumes and recognises that each culture has strengths and limitations, and, rather

than being viewed as deficient, differences between ethnic groups should be viewed as simply different. White and Parham (1990) opined that while the multicultural model is the latest trend in research with respect racial/ethnic groups in general and Blacks in particular, and is certainly a more positive approach to research with culturally distinct groups, it is by no means immune to the conceptual and methodological flaws of traditional psychology. While welcoming multiculturalism as becoming a "fourth force" in its influence on the field of mental health, Pedersen (1988) cautions against conceptualising multicultural counselling as a specialised aspect or sub-field of counselling. Establishing a specialised field of "multicultural counselling" he argues would be implying that the multicultural perspective is not relevant outside that specialized field when, in fact, to some extent all mental health counselling is multicultural. If we consider age, lifestyle, socioeconomic status, and gender differences in addition to ethnic and national differences, it quickly becomes apparent that there is a multicultural dimension in every aspect of mental health counselling (Pedersen, 1988). Bodibe (1993) identifies several factors accounting for the paucity of research from indigenous psychologists. These include finding topics for theses and dissertations acceptable to both student and supervisor, allocation of research grants, and the touchiness with which politically sensitive topics are regarded. To these I would add the dearth of suitable research mentors, nascent research capacity at most historically Black universities, and the editorial bias for positivistic research. Contesting the status quo The indictment that psychology has suffered from amnesia and has failed to fulfil its professional mandate to the culturally different has become endemic (Bulhan, 1985; Sue, 1981). The status of psychology is being increasingly contested by practitioners of all races (Katz, 1985) who have appealed to the profession to reexamine and re-evaluate the theory and practice base of psychology and its subdisciplines. Hence, more and more psychologists discontented with mainstream

psychology are calling for a theory and practice relevant to their particular sociocultural milieu (Anonymous, 1985; Berger & Lazarus, 1987; Bodibe, 1993; Holdstock, 1981) and for recognition of ethnic pluralism (White & Parham, 1990) and differences in world views in multicultural societies. A strong voice in this choir has come from African American psychologists who established their own professional association (Association of Black Psychologists) to give better articulation to their concerns. The call for a Black Psychology (White, 1972; White & Parham, 1990) and an Afrocentric perspective to psychology (Myers, 1988) has resounded from a growing discontent that traditional American psychology in all its varied forms has been insensitive to the needs of Black people. According to White and Parham (1990), the major forces that stimulated the growth of the contemporary Black psychology movement have been the failure of dominant psychology to provide a full and accurate understanding of Black reality and the dehumanisation of Black and other racial/ethnic groups resulting from the imposition and application of Eurocentric norms and values. As such, the emerging discipline of Black Psychology reflects an attempt to build a conceptual model that organises, explains, and leads to understanding the psychosocial behaviour of Blacks based on the primary dimensions of an Afrocentric world view. (White (1984) offers an excellent synthesis of the Afrocentric value system in The Psychology of Blacks. See also Bulhan's (1990) opening address at the Psychology and Apartheid conference). In accusing Black psychologists of complicity, Baldwin (1989) accused " ..we (Black) psychologists, by and large, have functioned in the service of the continued oppression and/or enslavement of Black people rather than in the service of our liberation from Western oppression and positive Black mental health (unconsciously on our part, no doubt, but the consequences are still the same) " (p.67). Fanon (1957; 1963; 1967), too, challenged Western scientists and psychologists in particular to consider their role in the creation, perpetuation, and consequences of racism and colonialism on oppressed groups or what he coined " the wretched of

the earth". So what can be done to challenge eurocentric domination in psychology? As the struggle against the hegemony of apartheid has demonstrated, the struggle against eurocentric domination of psychology must be engaged in at many different interfaces or sites of struggle. A recent article by Kriegler (1992) makes several salient suggestions to empower the profession to become a significant role player in the "new" South Africa. These include: creating more mental health posts in the state sector; improving psychology's location and role in the school setting; training more effective psychologists cost-effectively; grappling with political and crosscultural issues, and providing acceptable and accessible services. But, as long as psychology training programmes remain predominantly white, middle-class and maleoriented in terms of student and faculty numbers and training objectives, the press will be to maintain the present Eurocentric status quo in curriculum and training. Proactive recruitment, affirmative action, and opening up more training opportunities to other racial groups are a necessary first step towards establishing a critical mass to foment change from within. Attendant to increasing the cultural diversity in both student and staff components is the imperative to infuse training curricula with multicultural, cross-cultural, gender, and racial identity development emphases. Cross-cultural competence should not be seen as ancillary or merely a specialisation in psychology but as an integral part of competent counselling and psychotherapy (Kriegler, 1992; Pedersen, 1988). Training objectives also need to address more directly the manifest psycho-social problems and needs in the community. Currently training programmes in psychology remain too clinically focused. There is an overemphasis on the diagnosis and treatment of mental illness, without a corresponding emphasis on the broader health promotion and normal developmental concerns. We should be training for professional psychology which should include many techniques in addition to psychotherapy to include applications to human problems far afield from mental illness (Fox, 1994). Ability to work with

groups and to conduct workshops need to become training imperatives. Accessing, researching, and developing more relevant constructs, models, and theories that are more compatible with the reality of the oppressed are also essential. Rather than reinventing the wheel, progressive scholars may adapt much from seminal work already accumulated under the rubric of Afrocentric psychology, cross-cultural or multicultural counselling and indigenous psychology to shape the wheel of psychology to fit the South African context. In a similar vein, forging professional and personal links with committed individuals and associations in the diaspora may provide important sources of support and research collaboration. Eurocentric conceptions of science and research also must be contested. What a researcher proposes to study and how s/he interprets such findings are intimately linked to a personal, professional, and societal value system (Sue, Bernier, Durran, Feinberg, Pedersen, Smith, & Vasquez-Nuttall, 1982). Cross-cultural training will help to guide more relevant and meaningful emic (within culture) and etic (crossculture) research practice (Ponterotto & Casas, 1991). This advantage is underscored by Mio's (1989) assertion that knowledge of a culture is manifested in conceptualizations of problems and the means and goals for their resolutions. The lack of this knowledge and sensitivity may impose limitations on the nature and accuracy of research findings and interpretations, and in some cases tantamount to cultural oppression (Sue & Sue, 1990). Both emic and qualitative research methodologies lend themselves more fully to a dynamic understanding of culturallyspecific behaviour and present important alternatives and extensions to entrenched research traditions. A transformed or liberatory psychology needs to be weary of the dangers of professional elitism lest self-serving interests in professionalising psychology divert our attention and energies from grappling with the grave issues facing our nation in the times ahead. We need to seek ways of including (as opposed to claiming monopoly) and collaborating with other mental health professionals,

10

traditional healers, and service providers under the umbrella of an integrated community-based delivery system. Structured community psychology programmes emphasising preventive and promotive interventions in addition to curative may well be the vehicle to make psychology more accessible, accepting, and user-friendly to the majority of South Africans. CONCLUSION It is a Native American legend that when the earth begins to die as a result of all the harm inflicted upon it, warriors will arise from all over the world to heal the earth. These warriors will be known as warriors of the rainbow. As we face the challenges of transforming psychology and helping our nation to heal and grow healthy, mental health professionals have the imperative to recognise the biases of their training and their own ethnocentricism and have both a professional and moral obligation to learn how to engage in this rainbow dance in order to take up the challenges facing our society and profession.

11

REFERENCES Akbar, N. (1989). Chains and images of psychological slavery. Jersey City, NJ: New Minds Productions. Atkinson, D., Morten, G., & Sue, D.W. (1979). A cross-cultural perspective. Dubuque, IA: William C. Brown. Anonymous (1985). Some thoughts on a more relevant or indigenous counselling psychology in South Africa: Discovering the socio-political context of the oppressed. Psychology in Society, 5, 81-89. Barnes, E.J. (1972). Cultural retardation or shortcomings of assessment techniques? In R. L. Jones (ed), Black psychology. New York: Harper & Row. Baldwin, J. (1989). The role of black psychologists in black liberation. Journal of Black Psychology, 16(1), 67-76. Bergher, S., & Lazarus, S. (1987).The views of community organizers on the relevance of psychological practice in South Africa. Psychology in Society, 7, 6-23. Bodibe, R.C. (1993). What is the truth? Being more than just sjesting Pilate in South African psychology. South African Journal of Psychology, 23, 53-58. Brown, S.D., & Lent, R.W. (ed) (1984). Handbook of Counselling Psychology. New York: John Wiley & Sons. Bulhan, H.A. (1985). Frantz Fanon and the psychology of oppression. New York: Plenum Press. Bulhan, H.A. (1985). Afro-centric psychology: perspectives and practice. Opening address read at the UWC conference Psychology and Apartheid, November 1990. Fanon, F. (1959). A dying colonialism. New York: Grove Press. Fanon, F. (1963). The wretched of the earth. New York: Grove Press.

12

Fanon, F. (1967). Black skin, white mask. New York: Grove Press Fox, R.E. (1994). Training professional psychologists for the twenty-first century. American Psychologist, 49, 200-206. Guthrie, R. (1970). Even the rat was white. New York: Harper & Row. Holdstock, T.L. (1981). Psychology in South Africa belongs to the colonial era. Arrogance or ignorance? South African Journal of Psychology, 11,, 123-129. Jones, R. L. (ed) (1972). Black psychology. New York: Harper & Row. Katz, J. (1985). The sociopolitical nature of counselling. Counselling Psychologist, 13, 615-624. Kriegler, S. (1993). Options and directions for psychology within a framework for mental health services in South Africa. South African Journal of Psychology, 23, 64-70. Mio, J.S. (1989). Experiential involvement as an adjunct to teaching cultural sensitivity. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 17, 38-46. Myers, L. J. (1988). Understanding an Afrocentric world view. Duduque, IA: Kendal/Hunt. Parham, T. A. (1989). Cycles of Psychological Nigrescence. Counselling Psychologist, 17, 187-226. Pedersen, P. (ed) (1987). Handbook of cross-cultural counselling and therapy. New York: Praeger. Pedersen, P.B. (1988). The multicultural perspective as a fourth force in counseling. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 12, 93-95. Pontorotto, J.G., & Casas, J.M. (1991). Handbook of racial/ethnic minority counseling research. Springfield, Ill: Charles C Thomas. Smith, E. J. (1981). Cultural and historical perspectives in counselling blacks. In D.W. Sue (Ed.), Counselling the culturally different. New York: John Wiley &

13

Sons. Stewart, E. C. (1972). American cultural patterns. Yarmouth, ME: Intercultural Press. Sue, D. W. (1981). Counselling the culturally different. New York: John Wiley & Sons. Sue, D.W., Arredondo, P., & McDavis, R.J. (1992). Multicultural counseling competencies and standards: A call to the profession. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 20, 64- 88. Sue, D.W., Bernier, J.E., Durran, A., Feinberg, L., Pedersen, P., Smith, E.J., Vasquez-Nuttall, E. (1982). Position paper: Cross-cultural counseling competencies. The Counseling Psychologist, 10, 45-52. Sue, D.W., & Sue, D. (1990). Counseling the culturally different: Theory and practice. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons. Trimble, J. E., & Lafromboise, T. (1987). American Indians and the counselling process: culture, adaptation, and style. In P. Pedersen (Ed), Handbook of cross-cultural counselling and therapy. New York: Praeger. White, J.L. (1984). Toward a black psychology. In R. L. Jones (Ed), Black psychology. New York: Harper & Row. White, J. L., & Parham T.A. (1990). The psychology of blacks. Engelwood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall Williams, R. L. (1972). Abuses and misuses in testing black children. In R. L. Jones (Ed), Black psychology, New York: Harper & Row. Wrenn, C.G. (1962). The culturally encapsulated counselor. Harvard Educational Review, 32, 444-449.

14

TABLE 1: The Components of White Culture: Values and Beliefs _________________________________________________________________ Rugged Individualism: Individual is primary unit Individual has primary responsibility Independence and autonomy highly valued and rewarded Individual can control environment Competition: Winning is everything Win/lose dichotomy Action Orientation: Must master and control nature Must always do something about a situation Pragmatic/utilitarian view of life Decision Making: Majority rules when Whites have power Hierarchical Pyramid structure Communication: Standard English Written tradition Direct eye contact Limited physical contact Control emotions Time: Adherence to rigid time schedule Time is viewed as a commodity Protestant Work Ethic: Working hard brings success Progress and Future Orientation: Plan for the future Delay gratification Continual improvement and progress valued

15

Emphasis on Scientific Method: Objective, rational, linear thinking Cause and effect relationship Quantitative emphasis Dualistic thinking Power and Status: Measured by economic possessions Credentials, titles, positions Believe "own" system Believe better than other systems Family Structure: Nuclear family is ideal social unit Male is breadwinner and head of the household Female is homemaker and subordinate to the husband Patriarchal structure Aesthetics: Women's beauty based on blonde, blue-eyed, thin, young Men's attractiveness based on athletic ability, power, economic, and status (Katz,

1985, p.618)

16

TABLE 2: Cultural Components of Counselling: Values and Beliefs _________________________________________________________________ The Individual in Counselling: Individual is the primary focus Individual has primary responsibility Individual independence and autonomy highly valued Individual problems are intrapsychic and rooted in childhood and family Action Orientation: Client can master and control own life and environment Client needs to take action to resolve own problems Bias against passivity or inaction Status and Power: Belief that Western Counselling strategies are best Therapist is expert Credentials are essential Therapy is expensive Licensing used to maintain control of profession Processes (communication): Verbal communication or talk therapy Standard monocultural English Self-disclosure by client Direct eye contact Reflective listening Goals of counselling: Insight, self-awareness, and personal growth Improve social and personal efficiency Change individual behaviour Increase ability to cope Adapt to society's values Protestant Work Ethic: Work hard in counselling and counselling works for you Goal Orientation and Progress:

17

Belief in setting goals in counselling Belief in reaching goals in life Emphasis on Scientific Method: Therapist objective and neutral Rational and logical thought Use of linear problem solving Cause and effect relationships Reliance on quantitative evaluation, including psychodiagnostic tests, intelligence tests, personality inventories, and career placement Dualism between mind and body Label problems using DSM III Time: Schedule appointments Adherence to strict time schedule (50-minute hour) Family Structure: Nuclear family is ideal Aesthetics: YAVIS Client: young, attractive, verbal, intelligent, successful. (Katz, 1985, p.620)

18

You might also like

- BF01206194Document30 pagesBF01206194raishaNo ratings yet

- Marsella 2013 SR 2Document6 pagesMarsella 2013 SR 2Bernadette BasaNo ratings yet

- Dimensionalizing Cultures: The Hofstede Model in ContextDocument26 pagesDimensionalizing Cultures: The Hofstede Model in Contextgiomaram100% (1)

- Self As Cultural ProductDocument26 pagesSelf As Cultural ProductphuongphuongttNo ratings yet

- The Body of Faith: A Biological History of Religion in AmericaFrom EverandThe Body of Faith: A Biological History of Religion in AmericaNo ratings yet

- Dimensionalizing Cultures - The Hofstede Model in ContextDocument26 pagesDimensionalizing Cultures - The Hofstede Model in ContextSofía MendozaNo ratings yet

- Dimensionalizing Cultures - The Hofstede ModelDocument26 pagesDimensionalizing Cultures - The Hofstede ModelLaura ContrerasNo ratings yet

- Stereotypes and Violence: Global Humanities. Studies in Histories, Cultures, and Societies 04/2016From EverandStereotypes and Violence: Global Humanities. Studies in Histories, Cultures, and Societies 04/2016No ratings yet

- How Coloniality Shapes The Making of Latin American Psychologists: Ethnographic Evidence From EcuadorDocument12 pagesHow Coloniality Shapes The Making of Latin American Psychologists: Ethnographic Evidence From EcuadorjavierazoNo ratings yet

- Indigenous, Cultural, and Cross-Cultural Psychology: A Theoretical, Conceptual, and Epistemological Analysis Uichol KimDocument23 pagesIndigenous, Cultural, and Cross-Cultural Psychology: A Theoretical, Conceptual, and Epistemological Analysis Uichol KimUmmi LiyanaNo ratings yet

- Dimensionalizing Cultures - The Hofstede Model in ContextDocument26 pagesDimensionalizing Cultures - The Hofstede Model in ContextDani Pattinaja TalakuaNo ratings yet

- Culture HypnosisDocument48 pagesCulture HypnosisLore YukiNo ratings yet

- Decolonizing Post-Colonial Studies and Paradigms of Political EconomyDocument36 pagesDecolonizing Post-Colonial Studies and Paradigms of Political EconomyHilwan GivariNo ratings yet

- Theorizing Therapeutic Culture: Past Influences, Future DirectionsDocument16 pagesTheorizing Therapeutic Culture: Past Influences, Future DirectionsNicolasViottiNo ratings yet

- Losing Reality: On Cults, Cultism, and the Mindset of Political and Religious ZealotryFrom EverandLosing Reality: On Cults, Cultism, and the Mindset of Political and Religious ZealotryRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Verbs, Bones, and Brains: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Human NatureFrom EverandVerbs, Bones, and Brains: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Human NatureNo ratings yet

- Mesoudi CPhandbookDocument43 pagesMesoudi CPhandbookAYDIN YAZGI (야즈그)No ratings yet

- Culture and Depression: Studies in the Anthropology and Cross-Cultural Psychiatry of Affect and DisorderFrom EverandCulture and Depression: Studies in the Anthropology and Cross-Cultural Psychiatry of Affect and DisorderRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Transnational Cultural Flows - of Terapeutics Discourses - FinalDocument35 pagesTransnational Cultural Flows - of Terapeutics Discourses - FinalmonocongripeNo ratings yet

- DECOLONIZING POLITICAL-ECONOMY AND POST-COLONIAL STUDIES - TRANSMODERNITY, BORDER THINKING, AND GLOBAL COLONIALITY Ramón GrosfoguelDocument44 pagesDECOLONIZING POLITICAL-ECONOMY AND POST-COLONIAL STUDIES - TRANSMODERNITY, BORDER THINKING, AND GLOBAL COLONIALITY Ramón GrosfoguelJose LumbrerasNo ratings yet

- Foucault & Turn To Narrative TherapyDocument19 pagesFoucault & Turn To Narrative TherapyJuan AntonioNo ratings yet

- Cultural PyschiatryDocument9 pagesCultural PyschiatryGuillermo D'AcostaNo ratings yet

- Liberation Psychology from an Islamic PerspectiveDocument22 pagesLiberation Psychology from an Islamic PerspectiveRyehaNo ratings yet

- Relating Worlds of Racism: Dehumanisation, Belonging, and the Normativity of European WhitenessFrom EverandRelating Worlds of Racism: Dehumanisation, Belonging, and the Normativity of European WhitenessNo ratings yet

- Our Most Troubling Madness: Case Studies in Schizophrenia across CulturesFrom EverandOur Most Troubling Madness: Case Studies in Schizophrenia across CulturesProf. T.M. LuhrmannRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- 08.1b Essay Cultural Bias With CommentsDocument2 pages08.1b Essay Cultural Bias With Commentssabrina.ciara.daviesNo ratings yet

- Chapter IiDocument12 pagesChapter IiElixer ReolalasNo ratings yet

- Universalism without Uniformity: Explorations in Mind and CultureFrom EverandUniversalism without Uniformity: Explorations in Mind and CultureJulia L. CassanitiNo ratings yet

- From the Fat of Our Souls: Social Change, Political Process, and Medical Pluralism in BoliviaFrom EverandFrom the Fat of Our Souls: Social Change, Political Process, and Medical Pluralism in BoliviaNo ratings yet

- Kleinman, Suffering and Its Professional TransformationDocument18 pagesKleinman, Suffering and Its Professional Transformationrachel.avivNo ratings yet

- ASC233-Hollinsworth David-Race and Racism in Australia-Racism Concepts Theories and Approaches-Pp40-51Document13 pagesASC233-Hollinsworth David-Race and Racism in Australia-Racism Concepts Theories and Approaches-Pp40-51PNo ratings yet

- What Emotions Really Are: The Problem of Psychological CategoriesFrom EverandWhat Emotions Really Are: The Problem of Psychological CategoriesRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Anthropology Through a Double Lens: Public and Personal Worlds in Human TheoryFrom EverandAnthropology Through a Double Lens: Public and Personal Worlds in Human TheoryNo ratings yet

- Book Review of Handbook of Cultural Psychology Edited by Kitayama & CohenDocument8 pagesBook Review of Handbook of Cultural Psychology Edited by Kitayama & CohenChandan BilgundaNo ratings yet

- Crisis? What Crisis? Cross-Cultural Psychology's Appropriation of Cultural PsychologyDocument25 pagesCrisis? What Crisis? Cross-Cultural Psychology's Appropriation of Cultural PsychologyPablo MateusNo ratings yet

- Thought Reform and the Psychology of Totalism: A Study of 'brainwashing' in ChinaFrom EverandThought Reform and the Psychology of Totalism: A Study of 'brainwashing' in ChinaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (13)

- Antropologia and Dance JudithDocument10 pagesAntropologia and Dance JudithJavier GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Etnopsychoanalysis Culture, Trauma Gesine SturmDocument12 pagesEtnopsychoanalysis Culture, Trauma Gesine SturmEduardo Nogueira100% (1)

- Manly States: Masculinities, International Relations, and Gender PoliticsFrom EverandManly States: Masculinities, International Relations, and Gender PoliticsNo ratings yet

- Western and Non-Western Systems of Thought: Socio-Cognitive Worldviews, Regimes of Truth, and The Prospect of ConsilienceDocument16 pagesWestern and Non-Western Systems of Thought: Socio-Cognitive Worldviews, Regimes of Truth, and The Prospect of ConsilienceBrent CooperNo ratings yet

- c01BDocument3 pagesc01BPraveen Kumar ThotaNo ratings yet

- From Tao to Psychology: An Introduction to the Bridge Between East and WestFrom EverandFrom Tao to Psychology: An Introduction to the Bridge Between East and WestNo ratings yet

- AcculturationDocument30 pagesAcculturationMariaPapadopoulosNo ratings yet

- How Enemies Are Made: Towards a Theory of Ethnic and Religious ConflictFrom EverandHow Enemies Are Made: Towards a Theory of Ethnic and Religious ConflictNo ratings yet

- Preliminary InjunctionDocument6 pagesPreliminary InjunctionThe Salt Lake TribuneNo ratings yet

- Gay Test - Am I Gay, Straight, or Bisexual Take This Quiz To Find Out Now!Document1 pageGay Test - Am I Gay, Straight, or Bisexual Take This Quiz To Find Out Now!qjf6vv8t6qNo ratings yet

- Lean To Shed Plan: Free Streamlined VersionDocument9 pagesLean To Shed Plan: Free Streamlined VersionjesusdoliNo ratings yet

- Cost WaiveDocument3 pagesCost WaiveRimika ChauhanNo ratings yet

- Rare Book CategoryDocument2 pagesRare Book CategoryAri SudrajatNo ratings yet

- Written Notes of Arguments for bail CancellationDocument11 pagesWritten Notes of Arguments for bail CancellationShashiprakash MishraNo ratings yet

- EthicsJustice-And-Fairness Finals ReportingDocument38 pagesEthicsJustice-And-Fairness Finals ReportingannahsenemNo ratings yet

- Joanie Surposa Uy vs. Jose Ngo Chua G.R. No. 183965 September 18, 2009Document9 pagesJoanie Surposa Uy vs. Jose Ngo Chua G.R. No. 183965 September 18, 2009Ace GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Merciales v. CA G.R. No. 124171 PDFDocument4 pagesMerciales v. CA G.R. No. 124171 PDFIraNo ratings yet

- CIAC Jurisdiction Over Construction DisputeDocument3 pagesCIAC Jurisdiction Over Construction DisputeRoland Joseph MendozaNo ratings yet

- Poverty Alleviation and Distribution: Villanueva E. - Escobio - Morente - Roa - Orantia - PincasDocument45 pagesPoverty Alleviation and Distribution: Villanueva E. - Escobio - Morente - Roa - Orantia - PincasTin RobisoNo ratings yet

- Assignment #1 Globalization Topic MTHDocument3 pagesAssignment #1 Globalization Topic MTHJesse WrightNo ratings yet

- Deed of Absolute SaleDocument2 pagesDeed of Absolute SaleDaffodil Queen Poliquit DanosaNo ratings yet

- Revised Annex A for LGBT CoalitionDocument1 pageRevised Annex A for LGBT CoalitionJohn Marc FortugalizaNo ratings yet

- Shri Mata Vaishno Devi Shrine Board - Poojan Parchi Services 2Document1 pageShri Mata Vaishno Devi Shrine Board - Poojan Parchi Services 2Shreyash mathurNo ratings yet

- Clear Anti-Dandruff ShampooDocument1 pageClear Anti-Dandruff ShampooShehzad AhmadNo ratings yet

- ELP-L8 - Performance Task 1bDocument6 pagesELP-L8 - Performance Task 1bWilhelm Ritz Pardey RosalesNo ratings yet

- Test of Competence 2021 CBT Information Booklet For NursesDocument12 pagesTest of Competence 2021 CBT Information Booklet For NursesAppiah GodfredNo ratings yet

- Punjab Courts Act 1918Document24 pagesPunjab Courts Act 1918Taran Saini0% (1)

- Cole Porter song analysisDocument2 pagesCole Porter song analysisMisaelNo ratings yet

- Application To Issue The Judgment Trump v. MazarsDocument5 pagesApplication To Issue The Judgment Trump v. MazarsWashington Free BeaconNo ratings yet

- Court Declares Nullity of Marriage Due to Psychological IncapacityDocument14 pagesCourt Declares Nullity of Marriage Due to Psychological IncapacityCris Lloyd AlferezNo ratings yet

- Rig Com StationDocument4 pagesRig Com StationCristof Naek Halomoan TobingNo ratings yet

- ECB ManagersDocument3 pagesECB Managersnikitas666No ratings yet

- Basic Amc AcDocument12 pagesBasic Amc AcSATNAM SINGH LAMBANo ratings yet

- Petitioner Vs Vs Respondents: First DivisionDocument9 pagesPetitioner Vs Vs Respondents: First DivisionAdrian Jeremiah VargasNo ratings yet

- IDT Project PDFDocument25 pagesIDT Project PDFdivyansh nayarNo ratings yet

- Globalization Has Renovated The Globe From A Collection of Separate Communities InteractingDocument11 pagesGlobalization Has Renovated The Globe From A Collection of Separate Communities InteractingVya Lyane Espero CabadingNo ratings yet

- Empowered Lives Resilient Bangladesh - FINAL PDF KopiaDocument64 pagesEmpowered Lives Resilient Bangladesh - FINAL PDF KopiaKiran KumarNo ratings yet

- R0404 BD040722 QuippDocument5 pagesR0404 BD040722 QuippLovely Jane MorenoNo ratings yet