Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Psychological Health Research: Can Disability Studies and Psycology Co-Exist? - Kaley Maureen Roosen

Uploaded by

yorku_anthro_confOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Psychological Health Research: Can Disability Studies and Psycology Co-Exist? - Kaley Maureen Roosen

Uploaded by

yorku_anthro_confCopyright:

Available Formats

Psychological Health Research: Can Disability Studies and Psychology Co-exist?

Kaley Maureen Roosen, MA

Doctoral Student Clinical Psychology, York University, Toronto, ON

Abstract The aim of this paper is to study the psychological, social and political implications that can occur when a member of the disability community engages in the participation and introduction of research pertaining to the psychological health status of disabled persons. I propose that psychology can potentially offer a much needed service to the disability community in terms of research and psychological services. However, the challenge becomes shifting the established power differential within psychological research. Is it enough to have individuals with disabilities doing research on persons with disabilities? I will also discuss the complications that arise when the subjects problems closely resemble the researchers problems and the participants complaints about questionnairebased research are similar to my own woes within my own field as I struggle create changes to the structure and process of data collection.

s a clinical psychology student, the field is a complicated mix of clinical work, assessment, therapy, diagnosing, educating, listening, empathizing, and research aimed at understanding and uncovering the mysteries of human behaviour. All these duties encompass a complexly fused definition of what the field is; how do I, the individual, interact with this field? As a person with a physical disability, I can now acknowledge that my interest in psychology and disability stems from my own experiences; my personal frustrations with society, my own self and body and my hopes for an inclusive and empowering future for persons with disabilities. Although I do believe that having a passion for your research and clinical practice is essential, I have also come to realize this personal relationship comes riddled with conflict. Furthermore, the field of psychology research and clinical practice has a deeprooted history of idealizing objectivity as the goal (of research). The concept of objectivity manifests in the idea that the researcher is impartial and nonbiased. Double-blind research studies are the ideal within this conceptual format. The therapist is a blank slate and does not bring personal issues into the therapeutic allianceBut is this even possible? Can a personal passion not also be seen as an advantage? And how does one respond when the personal becomes too personal? How does one define this line? To begin, I will present a recent description of my recent fieldwork and the conflicts that arise when the personal becomes the topic of research and clinical work. Through many years of researching depression, social support, pain, eating disorders, I became increasingly disturbed by the lack of research on persons with disabilities. Every psychology text-book vehemently describes the importance of being aware of culture, and describes all the cultures to keep in mind. Always, there is a blatant disregard for the complexities of disability culture: It is not mentioned. The research that is detailed within these guides focuses on using disability as a comparison to the norm, as an example used to define whether an intervention is successful. The goal is to prevent disabilityIf you become disabled, you lose! As such, health is the absence of disability where disability correlates with everything negative. Psychology has been described as a

Keywords Psychology, rehabilitation, ethics, field-work

63 | Kaley Maureen Roosen

Playing the Field Conference Proceedings | Social Anthropology | York University 2009 pathologising, voyeuristic, individualizing, impairment-obsessed discipline that has contributed to the exclusion of people with impairments (Goodley & Lawthan 2005:136). When I entered into psychology seven-yearsago, I did so with no knowledge of this criticism. What do you mean, I thought? Psychology and psychologists help people and I want to help people; therefore, I am becoming a psychologist. However, experience has taught me differently and now I find myself at a crossroads. I still love the following aspects of psychology: 1) the idea of understanding the humanity of a person and facilitating personal growth and existential self actualization, 2) the idea that you cant get to where you are going until you understand and experience where you have been, and 3) the romanticism that everyone has a story and even the most despicable of humans can be understood and empathized with. I still love all these psychological ideals, but I cant ignore the politics and the practical assertions that come with the territory of being a disabled researcher in psychology and trying to be competitive but also socially conscious. As an example, I will go through my recent research experience working at a rehabilitation hospital and attempt to point out examples of how the personal became a conflict in the field. As I mentioned previously, inspired through my annoyance with the lack of psychological references to disability in any state, unless as a comparison to what doesnt work, I wanted to do relevant disability related research. I wanted to combine psychological issues with physical ones and contribute to the literature and research for disabled people. My motivations to follow this trajectory emerged partly due to my own experiences with medical doctors who focused so much on my physical state that I felt my emotional needs were stifled. As a result, I began to work more within the health field, in a hospital. However, it has been my experience that some professionals question the appropriateness for researchers with disabilities to work with disabled persons. I was encouraged to could keep an emotional distance But wait a minute, is this even possible? How could I keep emotional distance? What if I could offer some suggestion to an individual struggling through a confusing system that I may have already wondered through? Wouldnt my passion for disability and personal experience guide me more than hold me back? I guess I would have to start the position to find out. The position I took was as a research assistant. My duties included calling individuals with severe mobility impairments and asking them to answer questionnaire-based surveys about their health status, how much care-giving help they need, their subjective and objective quality of life and how much their disability cost our society. It is difficult to think of ones existence as costly. The rewarding, yet often frustrating part about research is the fact that it always attempts to have an impact socially. The broader impact of this study is clear: We need to show persons with disabilities as suffering. The more they are using health care dollars, the more they are suffering, the greater the social burden they are, the more research and clinical funding the government will distribute to support them. If we did more realistic research, or perhaps changed our perspective to examine the positive aspects of disability, can you imagine how happy political bureaucrats would be? They might ask questions like: If they are doing so well, why do we need to give money for research to help them? Why do we need to fund charitable organizations like March of Dimes if in fact they are able to help themselves? Whats the point of putting money into health services for persons with disabilities if they are healthy and happy? Even while I was surveying these people, I cringed. The questions began with a long list of health problems and participants were asked to indicate how much the health problems interfered with their life. Then they were asked questions regarding how satisfied participants were with their life. The most common answer, Well, I am in a wheelchair, so what do you think? Or, I am happy with my life if I wasnt in a wheelchair and this often results with an initial refusal to provide a rating, and thus the clinician encourages a response or the data is not usable. The clinician

64 | Kaley Maureen Roosen

Playing the Field Conference Proceedings | Social Anthropology | York University 2009 in me wants to agree with the participants. I want to respond, These questions are difficult. I understand, It sounds like you are having a hard time in some aspects of your life and not others which makes these extremely black and white questions difficult to reconcile But the researcher in me pushes on: Ok, if you had to pick a number from 1 to 7 based on how satisfied with your life, what would it be? This can often result in a lower number. They dont feel privileged enough to pick a high number for they feel that they live their life in a wheelchair is reason enough for them to be dissatisfied. In a way, who am I to judge their happiness? I myself find my life worthwhile and productive as a member of a disadvantaged population. However, these individuals put my own limitations at the forefront of my awareness and I find myself questioning my own positive view on life and subsequently, experience difficulties relaying these negative outcomes. In another way, perhaps a more significant way, I get frustrated with what I perceive to be societal internalization that a disabling embodiment is, by definition, not as fulfilling or satisfying as a non-disabling embodiment. And the research questions continue to baffle the constituents. For example, consider a question which asks a person with a physical disability how mobile they are, are not -or rather may never be. It reads, During the past four weeks, have you been able to run, jump, walk and bend without difficulty? Yes or No. This scale examines the level an individual matches the ideal perception of how a functioning member of society should behave (i.e., going to work and participating in the community). It was used primarily for assessing quality of life based on very straightforward questions of mobility, sensory acuity, psychological functioning and presence or absence of pain through very ablest assumptions. Who says quality of life is based on how much newsprint you can read? How much you are able to run, walk, jump or bend? Or, how often you are feeling fretful, angry, irritable, anxious or upset? This is clearly an example of a powerful cultural and social system normalizing views of what it means to be healthy and hence Happy, successful and a proud level of quality of life. And, no matter how you frame the questions, it inherently will portray persons without the ability to walk, bend, jump or jump without difficulty as suffering, as having a very low quality of life and as being unhealthy. And what were the initial results of the questionnaires I administered? Well, a quality-oflife-score of zero represents no quality of life. Our results that represented the responses of persons with disabilities were close to zero. In other words, our participants have such an incredibly low quality of life that, according to this survey, they are doing worse than a deceased person or in other more evocative language, our participants specifically, people with disabilities, feel as though they are better off being dead. Talk about results having a large societal impact! I guess if you want people to think you are suffering and the government health-care spending agencies to believe that you are a costly group of people who are living but feel as though they would be better off dead then this is a great result. Part of me thinks its necessary for this type of result to be made public because perhaps if we treated their health conditions with more compassion, they would have a better quality of life. On the other hand, how frustrating! Is this our only way of getting the support we need to live from bureaucrats? By showing us as pathetic helpless people suffering from our medical conditions? Evidently, in order to secure additional and continued health care funding from government agencies, disabled people must negotiate how they are perceived by others, thereby, often reinforcing stereotypes of vulnerability and helplessness. You will notice my language changed just now from participants to us because I am not an objective observer. I get emotional when I am interviewing these people. I do empathize with them that these questions are difficult and do not apply to real life people, but I still insist they pick a number on the scale. This project challenges my own passion for research as I view research as a potential avenue to promote systemic change. I want to be a successful researcher so that when I have my own lab, getting there by publishing and following the politics of being a grad student, I can change this research practice

65 | Kaley Maureen Roosen

Playing the Field Conference Proceedings | Social Anthropology | York University 2009 to be more systemic. Can we not show these participants as not being victims of their medical conditions, but victims of a disabling society? One that does not hire them for jobs, so they are stuck at home answering questionnaires from researchers like me; one that does not give them enough attendant support services so that they have to live in homes or rely on their family to help them and again cant work? And, can we not show how we do not have enough adequate transportation to allow them to become fully functioning members of a community? And so on. How would government funding services respond to this type of research? These are the multiple questions that I hope more experience will answer. Besides the research aspect of my work, I am also training to be a clinical psychologist. I want to be a therapist. I want to co-construct new meaning of embodiment in disabled persons lives, and also in nondisabled persons lives. I am early in my career, but have already starting thinking about the therapeutic implications of myself, a disabled person, wanting to work with disabled clients. In many respects, I dont see any issues and mostly notice the benefits of being able to really connect with another individual who is also disabled. We are both members of the same crip culture; we are both victims of societal discrimination and degradation; and we are both victims of disabling barriers. Additionally, we are both members of a community pushed through the medical system and both struggle with medical identities and realities, such as pain. It is fairy similar to a client preference to seeing a therapist from a similar cultural or ethnic or religious background. This cultural pairing is overwhelmingly supported in psychology circles, it even has a label: Multicultural Counselling. However, the idea of a disabled counselor with a disabled client is not widely supported. Counter-transference is a psychoanalytic term used to describe when a therapist reacts to the personal attributes of a client because he or she has not yet dealt with the psychological turmoil of their own life. Disability has a long history in psychology as being psychologically pathological. Freud once described persons with physical disabilities as being unable to be psychoanalyzed because they cannot ever fully overcome their ego defenses because it would be too much of a psychic crisis to admit the overwhelming tragic nature of their existence (Freud 1920). Following Freud, there has been many examples of psychologists describing disabled persons as difficult to treat and inherently pathological (e.g. Fow 1998). Therefore, it comes as no surprise that a disabled therapist is seen as unable to fully help another with a disability as he or she is not a fully functioning psychological person. How can he or she help another person with a disability without stimulating a psychic crisis within themselves? I personally dont believe this. Sure, I acknowledge that I probably will have a more personal reaction to disabled persons who resemble my own situation, but I anticipate a unique experience from every client, disabled or not and my role is to immerse myself into their personal experience to facilitate emotional growth. One area where I do anticipate conflict to emerge is the attempt to hold back my own personal beliefs that society has such an intense negative message about disability; it is difficult for disabled persons not to internalize this message. As I myself become aware of how much I have internalized this message and allowed it to influence my own being, how can I help clients see how they have internalized it? I often found myself wanting to yell at my research participants when I asked them about their satisfaction with life. They would answer, Well I am in a wheelchair, what do you think my life is like? I was tempted to respond, Well so am I and I dont feel that being in a wheelchair means a person has a hopeless life. But who am I to push my own beliefs onto others? I do not want to assume power over another individual by promoting a view that perhaps I, the therapist, have insiders knowledge on what is the better way to view the world. However, part of me feels like perhaps I can help them to realize that they are internalizing this negative societal message. The problem becomes that I am then demonstrating a paternalistic-like moral position that sets the standards for how others should think, feel and exist.

66 | Kaley Maureen Roosen

Playing the Field Conference Proceedings | Social Anthropology | York University 2009 My clinical and research fieldwork within clinical psychology has been riddled with issues, conflicts and moral conundrums that have challenged my own identity as a future clinical psychologist, future researcher and a socially conscious disabled person. And although I am left with more questions than answers at this point in my career and life experience, I am grateful for these practical experiences. Without the complicated fieldwork, I would still be going into this life choice thinking in ideal terms that I was going to save other disabled people through research and counseling, when really I am the one who needed savingSocially conscientious and awareness type saving! Now I can see fieldwork and the emotional, social, psychological, and political journey as opportunities for personal growth as a person and a researcher and clinician. Can I combine my ideal world of psychological self-actualization and humanistic emotional growth with critical disability examination and objections? I would like to believe so, and I know that my research and my practice will ultimately have to have a critical disability slant. I can no longer accept that my perspective can be represented without knowledge of the societal impact that every action I undertake has and thus every sense of embodiment I have had, has been influenced by it. And in the end, I think that is the real resolution: the knowledge that there is no answer except to continue to be aware and grow with experience in a way that you can be true to your own passion and self.

Goodley, D., & Lawthom, R. 2005 Epistemological journeys in participatory action research: alliances between community psychology and disability studies. Disability & Society 20: 135-151.

Kaley Roosen is a 2nd Year PhD student in

Clinical Psychology at York University, Toronto, ON.

References Fow, N. R. 1998 Supportive psychotherapy and psychological adjustment to physical disability. Journal of Applied Rehabilitation Counseling 29: 20-24.. Freud, S. 1920 The libido theory and narcism. In A general introduction to psychoanalysis. Pp. 356371. New York, NY: Horace Liveright.

67 | Kaley Maureen Roosen

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- School M&E System HandbookDocument61 pagesSchool M&E System HandbookVictoria Beltran Subaran86% (29)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Teaching Guide For English For Academic and Professional PurposesDocument3 pagesTeaching Guide For English For Academic and Professional PurposesMIMOYOU100% (2)

- My Personal Teaching PhilosophyDocument1 pageMy Personal Teaching Philosophyapi-193964377No ratings yet

- Feeding Program Narrative Report Sy 2018 - 2019Document3 pagesFeeding Program Narrative Report Sy 2018 - 2019Daiseree Salvador100% (2)

- Playing The Field - Table of ContentsDocument1 pagePlaying The Field - Table of Contentsyorku_anthro_confNo ratings yet

- Playing The Field - AcknowledgementsDocument1 pagePlaying The Field - Acknowledgementsyorku_anthro_confNo ratings yet

- Playing The Field - Publication Info and CopyrightDocument1 pagePlaying The Field - Publication Info and Copyrightyorku_anthro_confNo ratings yet

- Playing The Field - Front CoverDocument1 pagePlaying The Field - Front Coveryorku_anthro_confNo ratings yet

- Fielding An Anti-Capitalist Anthropology - Ted BakerDocument5 pagesFielding An Anti-Capitalist Anthropology - Ted Bakeryorku_anthro_confNo ratings yet

- Disability Studies Fieldwork - Jen RinaldiDocument5 pagesDisability Studies Fieldwork - Jen Rinaldiyorku_anthro_confNo ratings yet

- Viratha: Conceptualizing Femail Religious Agency - Susan McNaughtonDocument5 pagesViratha: Conceptualizing Femail Religious Agency - Susan McNaughtonyorku_anthro_confNo ratings yet

- Researching "Traffic": Methodological Approaches For Navigating The Congestion in Women's Health Policy - Michelle Wyndham-WestDocument7 pagesResearching "Traffic": Methodological Approaches For Navigating The Congestion in Women's Health Policy - Michelle Wyndham-Westyorku_anthro_confNo ratings yet

- Pervertible Practices: Playing Anthropology in BDSM - Claire DalmynDocument5 pagesPervertible Practices: Playing Anthropology in BDSM - Claire Dalmynyorku_anthro_confNo ratings yet

- The Sound of Home - Implications of Living in The Field - Samantha BreslinDocument5 pagesThe Sound of Home - Implications of Living in The Field - Samantha Breslinyorku_anthro_confNo ratings yet

- Textual Healings: Conversations About Protecting Privelege Through Subversive Research - Tricia Morris and Katie MacdonaldDocument7 pagesTextual Healings: Conversations About Protecting Privelege Through Subversive Research - Tricia Morris and Katie Macdonaldyorku_anthro_confNo ratings yet

- Prefigurative Politics and Anthropological Methodologies - Niki ThorneDocument7 pagesPrefigurative Politics and Anthropological Methodologies - Niki Thorneyorku_anthro_confNo ratings yet

- Locating The Ghost and The Work of Haunting in Toni Morrison's Fiction and Non-Fiction - Kama MaureemootooDocument5 pagesLocating The Ghost and The Work of Haunting in Toni Morrison's Fiction and Non-Fiction - Kama Maureemootooyorku_anthro_confNo ratings yet

- Surprises and Trends Revealed During Fieldwork - Marta SilvaDocument4 pagesSurprises and Trends Revealed During Fieldwork - Marta Silvayorku_anthro_confNo ratings yet

- ADHD, An Entity Within The Crisis of The Field - Jesse P. HiltzDocument5 pagesADHD, An Entity Within The Crisis of The Field - Jesse P. Hiltzyorku_anthro_confNo ratings yet

- Activism and The Academy - Jean McDonaldDocument5 pagesActivism and The Academy - Jean McDonaldyorku_anthro_confNo ratings yet

- Disability Fieldwork:What Disabled Fieldworkers Bring To The Field and Leave Behind - Athena GoodfellowDocument5 pagesDisability Fieldwork:What Disabled Fieldworkers Bring To The Field and Leave Behind - Athena Goodfellowyorku_anthro_confNo ratings yet

- Understanding The Field of Literary Editing - Alicia FaheyDocument5 pagesUnderstanding The Field of Literary Editing - Alicia Faheyyorku_anthro_confNo ratings yet

- Playing The Field Conference CompleteDocument84 pagesPlaying The Field Conference Completeyorku_anthro_confNo ratings yet

- A Lesson Plan TemplateDocument4 pagesA Lesson Plan TemplateEmmaNo ratings yet

- Session I-Certificate Programme For Professional Development of Primary TeachersDocument20 pagesSession I-Certificate Programme For Professional Development of Primary TeachersNavaneethMahendranNo ratings yet

- Nicole Altseimer - Resume November 2014 ShortenedDocument3 pagesNicole Altseimer - Resume November 2014 Shortenedapi-273242824No ratings yet

- Research QuestionnaireDocument2 pagesResearch QuestionnaireEmmanuel UwadoneNo ratings yet

- Cambridge Aice Brochure As and A LevelDocument2 pagesCambridge Aice Brochure As and A Levelapi-294488294No ratings yet

- Parent Satisfaction SurveyDocument5 pagesParent Satisfaction Surveyenu76No ratings yet

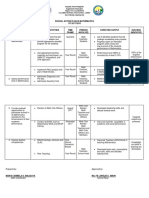

- Teacher's M&E Report: Curriculum Implementation 1. Curriculum Coverage 3. Failures 4. Learning ResourcesDocument4 pagesTeacher's M&E Report: Curriculum Implementation 1. Curriculum Coverage 3. Failures 4. Learning ResourcesGenus LuzaresNo ratings yet

- TSL 3123 Topic 4 Basic Principles of AssessmentDocument17 pagesTSL 3123 Topic 4 Basic Principles of AssessmentFaruqkokoNo ratings yet

- Alisha Full ResumeDocument2 pagesAlisha Full Resumeapi-230530007No ratings yet

- Psychology - Class XII - Chapter 01Document22 pagesPsychology - Class XII - Chapter 01shaannivasNo ratings yet

- Preschool Brochure 3 PDFDocument2 pagesPreschool Brochure 3 PDFYudiMeidiyansah100% (1)

- FS 5 Episode 8Document15 pagesFS 5 Episode 8nissi guingab61% (41)

- Action Plan in Mathematics Sy 2017-18Document2 pagesAction Plan in Mathematics Sy 2017-18Maria Carmela Oriel Maligaya88% (17)

- Kerala EconomyDocument114 pagesKerala EconomyPrasad AlexNo ratings yet

- Table of Equivalence Primary and Secondary PDFDocument1 pageTable of Equivalence Primary and Secondary PDFamfipolitisNo ratings yet

- Reflective Analysis of Portfolio Artifact ST 4Document1 pageReflective Analysis of Portfolio Artifact ST 4api-250867686No ratings yet

- Decomposing Lesson Commentary - Crystal PuentesDocument2 pagesDecomposing Lesson Commentary - Crystal Puentesapi-245889868No ratings yet

- Enhancing Teacher LeadershipDocument43 pagesEnhancing Teacher LeadershipJoanna Fajardo GarciaNo ratings yet

- Goals Reflection PaperDocument6 pagesGoals Reflection Paperapi-242146955No ratings yet

- PLC Assessment - RevisedDocument3 pagesPLC Assessment - RevisedJill GoughNo ratings yet

- Hris Template 2013 2Document26 pagesHris Template 2013 2Maisa Rose Bautista VallesterosNo ratings yet

- Final Paper Professional Dev Plan702Document11 pagesFinal Paper Professional Dev Plan702westonfellowsNo ratings yet

- Van Brakel Measuring StigmaDocument12 pagesVan Brakel Measuring StigmaKaterinaStergiouliNo ratings yet

- Rationale Statement Welcome Letter Standard TenDocument3 pagesRationale Statement Welcome Letter Standard Tenapi-284019853No ratings yet

- Kuliah 2 EDUP3063 Peranan Dan Tujuan Pentaksiran Dalam PendidikanDocument9 pagesKuliah 2 EDUP3063 Peranan Dan Tujuan Pentaksiran Dalam PendidikanJiing TeohNo ratings yet

- Mini Lesson Switz Brown BearDocument2 pagesMini Lesson Switz Brown Bearapi-248710381No ratings yet