Professional Documents

Culture Documents

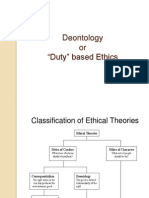

Consequential Ism

Uploaded by

Charles StoyOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Consequential Ism

Uploaded by

Charles StoyCopyright:

Available Formats

G. E. M.

Anscombe, whose previously mentioned paper coined the term "consequentialism",[1] objects to consequentialism on the grounds that it does not provide guidance in what one ought to do, since the rightness or wrongness of an action is determined based on the consequences it produces. Furthermore, she argues that consequentialism since Henry Sidgwick denies that there is any distinction between consequences that are foreseen and those that are intended (see Principle of double effect). Finally, Anscombe objects to the very character of consequentialism itself insofar as it is concerned with determining the rightness and wrongness of actions. She argues that the distinction between right action and wrong action only makes sense within the framework of Judeo-Christian divine lawand, according to Anscombe, Judeo-Christian divine law is incompatible with consequentialism. The DDE seems to require distinguishing between intended means and (foreseeable) mere side effects. A critic of DDE might say that this distinction has no moral significance. Both are foreseen or foreseeable, and so the only relevant difference must be in the causal relationships (where one harm is a harmful means and the other harm is a harmful consequence). However, a difference in causal relationships is not itself of moral significance according to DDE, because DDE admits that disproportionately harmful consequences are morally unacceptable. Therefore there is neither a psychological nor causal difference between intended means and (foreseeable) mere side effects, and the distinction is questionable. On this interpretation of DDE, mere side effects are limited to side effects that are unavoidable, either because they are brought about by every available means to the intended good consequence or because they are the side effects of the choice that minimizes harmful side effects in keeping with the proportionality requirement. As such, DDE tells us that agents are morally obligated to choose, from among alternative means, that which achieves the intended aim with the minimum of foreseeable harmful effects, for only the minimum harm can be counted as mere side effects. Any foreseeable harmful effects beyond this level are intended side effects for which the agent is morally responsible. For example, if your cannot earn a living without owning an automobile, you are morally obligated to own the automobile that produces the least pollution, the lowest risk of accidents, and so on for the class of automobiles that you can afford. If you could afford to own a car that would pollute less than the one you drive, then the additional pollution that you generate cannot be dismissed as a mere side effect of your transportation Buddhism links karma directly to the motives behind an action. Motivation usually makes the difference between "good" and "bad" actions; but included in the motivation is also the aspect of ignorance such that a well-intended action from an ignorant mind can subsequently be interpreted as a "bad" action in the sense that it creates unpleasant results for the "actor".

Consequentialism is a moral theory which states that the consequences of a persons actions are the true basis for judging the morality of that action, whether an action is right or wrong. A variation is motive consequentialism. The consequences which arise from a choice are entailed in the motive(s) to choose that action over other actions. A critique of consequentialism finds three problematic areas: consequentialism does not say what a person ought to do, there is no distinction between foreseen consequences and those that are intended, and the concept of right or wrong only makes sense within the confines of Judeo-Christian divine law. The second criticism centers on intended consequences and those that are foreseen. For example, I purchase an automobile. The purchase is necessary in order for me to go to work. Work is essential in the society I live in for my existence. Yet the purchase of the vehicle means that I also add to the pollution contaminating my immediate environment and harming others in my community. Consequentialism seems to point to making a choice that achieves the intended consequences at the same time of minimizing harmful side effects. Those negative consequences beyond those desired minimized side effects are intended. The Buddhist concept of karma seems to imply that if a person is makes a choice out of ignorance, even if well intended, is a bad decision. Conversely, if a person makes a choice out of full awareness, that decision is a good decision. In short, a person is bound by the full consequences of the choice made, regardless of whether the decision was undertaken with full knowledge of all the consequences or not. This would imply that all choices made by the majority of people are bad decisions. To follow Socrates example of withholding a dagger from the deranged owner would be a bad decision. Is this necessarily so?

You might also like

- Lecture 3Document2 pagesLecture 3Noshaba SharifNo ratings yet

- NATURALS: The Origin, Background, and Evolutionary Adaptive Strategy of Womanizers, Pimps, Bad Boys, Players,and Certain Dysfunctional Men.From EverandNATURALS: The Origin, Background, and Evolutionary Adaptive Strategy of Womanizers, Pimps, Bad Boys, Players,and Certain Dysfunctional Men.No ratings yet

- Week011 Module ActionsandConsequencesDocument7 pagesWeek011 Module ActionsandConsequencesRoxe DacNo ratings yet

- ConsequentialismDocument6 pagesConsequentialismAnto PuthusseryNo ratings yet

- Ethical DelimasDocument10 pagesEthical DelimasEngr Danyal ZahidNo ratings yet

- Consequentialism Moral TheoryDocument29 pagesConsequentialism Moral TheoryRICARDO ANDRES TOSCANO VILLAMIZARNo ratings yet

- Intentional Action and The Praise-Blame AsymmetryDocument16 pagesIntentional Action and The Praise-Blame AsymmetryRuxandra DiaconescuNo ratings yet

- Actus Reus Theory Revision Notes-2Document5 pagesActus Reus Theory Revision Notes-2Syed Hassan KhalidNo ratings yet

- C. Consequentialist Theories: Consequentialism: An Action Is Morally Right If The Consequences of That Action Are MoreDocument3 pagesC. Consequentialist Theories: Consequentialism: An Action Is Morally Right If The Consequences of That Action Are MoreRica RaviaNo ratings yet

- Moral Philosophy and Social Work PolicyDocument14 pagesMoral Philosophy and Social Work Policybonny7No ratings yet

- Immanuel Kant and Hedonic Aspect of UtilitarianismDocument11 pagesImmanuel Kant and Hedonic Aspect of Utilitarianismripa.akterNo ratings yet

- First, Do Not HarmDocument14 pagesFirst, Do Not HarmVicky LouNo ratings yet

- J. Baron, Do No HarmDocument13 pagesJ. Baron, Do No HarmJonathan MenezesNo ratings yet

- 3 UtilitarianismDocument24 pages3 UtilitarianismJasmine TsangNo ratings yet

- Module 1 AssignmentDocument4 pagesModule 1 AssignmentWinston QuilatonNo ratings yet

- Forum 2 McFarland Utilitarianism QuestionsDocument9 pagesForum 2 McFarland Utilitarianism QuestionsThy NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Consequentialism 1Document14 pagesConsequentialism 1shanikaNo ratings yet

- Hyundai Kona Gdi 2-0-2019 Wiring DiagramDocument22 pagesHyundai Kona Gdi 2-0-2019 Wiring Diagrammistythompson020399sdz96% (28)

- Activities in Chapter 4 (Lesson 2)Document3 pagesActivities in Chapter 4 (Lesson 2)Juneriza SamsonNo ratings yet

- Why Keeping Your Promise - Hedwig 2019Document12 pagesWhy Keeping Your Promise - Hedwig 2019Hedwig FossenNo ratings yet

- Deontology and UtilitarianismDocument6 pagesDeontology and UtilitarianismPrakhar NemaNo ratings yet

- NCFL 2018 NegDocument17 pagesNCFL 2018 NegGene LuNo ratings yet

- Class Notes For Moral DilemmasDocument2 pagesClass Notes For Moral Dilemmaslescouttfromtf2No ratings yet

- Kant and Deontological Theories of EthicsDocument2 pagesKant and Deontological Theories of EthicsP.Sanskar NaiduNo ratings yet

- PunishmentDocument7 pagesPunishmentadamjoy_95No ratings yet

- Excuse, Capacity and Convention: David OwensDocument12 pagesExcuse, Capacity and Convention: David OwensThomas belgNo ratings yet

- Teleology FinalDocument31 pagesTeleology FinalRoshni BhatiaNo ratings yet

- Causation NotesDocument6 pagesCausation NotesNikhil KumarNo ratings yet

- Teleological TheoryDocument5 pagesTeleological TheoryNelly PerezNo ratings yet

- Ethics QuizDocument3 pagesEthics QuizathierahNo ratings yet

- Unit 3 Eed1 ReviewerDocument11 pagesUnit 3 Eed1 Revieweralexaaluan321No ratings yet

- Final DeontologyDocument31 pagesFinal DeontologyRoshni BhatiaNo ratings yet

- From? Being Considered Age-Inappropriate. It Is Listed Variously As Suggested ForDocument12 pagesFrom? Being Considered Age-Inappropriate. It Is Listed Variously As Suggested ForRahul JainNo ratings yet

- At K FW - The Doctrine of Double EffectDocument2 pagesAt K FW - The Doctrine of Double EffectaesopwNo ratings yet

- Basic Ethical Principles 1. StewardshipDocument5 pagesBasic Ethical Principles 1. Stewardshipmitsuki_sylph83% (6)

- Deontology:: Pluralist Vs Conventional UtilitariansDocument2 pagesDeontology:: Pluralist Vs Conventional UtilitariansKishan PatelNo ratings yet

- Assignment Civic and MoralDocument6 pagesAssignment Civic and MoralmohamedNo ratings yet

- Isip, Erwin Gabriel C.Document6 pagesIsip, Erwin Gabriel C.Erwin IsipNo ratings yet

- Morality According To Natural Law and UtilitarianismDocument6 pagesMorality According To Natural Law and UtilitarianismCharlesNo ratings yet

- Daque Assignment01Document4 pagesDaque Assignment01Krisca DianeNo ratings yet

- 02 Handout 1Document5 pages02 Handout 1Katelyn Mae SungcangNo ratings yet

- Burt 2014 SelfControlandCrimeDocument42 pagesBurt 2014 SelfControlandCrimeanggi hermandaNo ratings yet

- A Punitive Measure That The Law Imposes For The Performance of An Act That Is Proscribed, or For The Failure To Perform A Required ActDocument21 pagesA Punitive Measure That The Law Imposes For The Performance of An Act That Is Proscribed, or For The Failure To Perform A Required ActJohn Cloyd RefaniNo ratings yet

- Ethics-Whistle Blowing Info - ShenaeDocument5 pagesEthics-Whistle Blowing Info - ShenaeShenae Adams100% (1)

- Doctrine of Double EffectDocument3 pagesDoctrine of Double EffectRael VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- ETHICS 1.3.READING MATERIAL CombinedDocument14 pagesETHICS 1.3.READING MATERIAL CombinedJohnny King ReyesNo ratings yet

- Government Coercion Threatens Individual Freedom and Renders Morality MeaninglessDocument15 pagesGovernment Coercion Threatens Individual Freedom and Renders Morality MeaninglessCalen John SmithNo ratings yet

- Concept of Crime and PunishmentDocument3 pagesConcept of Crime and Punishmentdradnanlaw21No ratings yet

- EthicsDocument2 pagesEthicsYesha Jade SaturiusNo ratings yet

- AT "My Side Is An Omission"Document3 pagesAT "My Side Is An Omission"Tanish KothariNo ratings yet

- The Principle of Autonomy: Four Fundamental Ethical PrinciplesDocument7 pagesThe Principle of Autonomy: Four Fundamental Ethical PrinciplesROMELA MAQUILINGNo ratings yet

- JurisDocument5 pagesJurisPrabhsimran SinghNo ratings yet

- Actus Hominis.: Causa. This Distinction of Direct and Indirect Willing (Or Direct and Indirect Voluntariness) Raises ADocument7 pagesActus Hominis.: Causa. This Distinction of Direct and Indirect Willing (Or Direct and Indirect Voluntariness) Raises AChristine GreyNo ratings yet

- R7Deontological EthicsDocument4 pagesR7Deontological Ethicsjefferyi silvioNo ratings yet

- Act UtilitarianismDocument21 pagesAct UtilitarianismTony BlairNo ratings yet

- AAU Civic and Ethical Education AssignmentDocument16 pagesAAU Civic and Ethical Education AssignmentnahNo ratings yet

- Ethics VoluntarinessDocument24 pagesEthics VoluntarinessRod Leonard GeonagaNo ratings yet

- ETHICSASSIGNMENTTWO14Document8 pagesETHICSASSIGNMENTTWO14Patrick ChibabulaNo ratings yet

- w0510 01Document6 pagesw0510 01Jone LasNo ratings yet

- What Is SinDocument21 pagesWhat Is Sinranmao1408No ratings yet

- A Civilization of LoveDocument3 pagesA Civilization of LoveRoma IgnacioNo ratings yet

- An Essay Worth Sharing - Joan Didion's On Self Respect' Word On The StreetDocument13 pagesAn Essay Worth Sharing - Joan Didion's On Self Respect' Word On The Streetkeith5No ratings yet

- Brand ArchetypesDocument15 pagesBrand ArchetypesMartin Headon100% (5)

- Anger ManagementDocument14 pagesAnger ManagementMariam Sattar100% (1)

- Taking The One Seat Written Material PDFDocument69 pagesTaking The One Seat Written Material PDFSamuel Long100% (1)

- DajjalDocument3 pagesDajjalNaeem Muhammad KhanNo ratings yet

- The Picture of Dorian Gray PDFDocument13 pagesThe Picture of Dorian Gray PDFDaniel ArizabalNo ratings yet

- Jane EyreDocument6 pagesJane EyreBianca DarieNo ratings yet

- National Values BookletDocument9 pagesNational Values BookletWanjikũRevolution KenyaNo ratings yet

- S.richardson and H.fieldingDocument4 pagesS.richardson and H.fieldingElena LilianaNo ratings yet

- The Ambivalence of Filipino Traits and ValuesDocument6 pagesThe Ambivalence of Filipino Traits and ValuesJade DeopidoNo ratings yet

- TEss As Pure WomanDocument2 pagesTEss As Pure WomanKashif WaqasNo ratings yet

- Lista de Verbos IrregularesDocument8 pagesLista de Verbos IrregularesCruz Zamora SharkconectionNo ratings yet

- QuotesDocument21 pagesQuotesShamini ShanmugalingamNo ratings yet

- What Is An Educated Filipino?: By: Francisco BenitezDocument6 pagesWhat Is An Educated Filipino?: By: Francisco BenitezFarah Tolentino NamiNo ratings yet

- Essay of Cid As An Epic HeroDocument4 pagesEssay of Cid As An Epic HeroJaime Daniel BlancoNo ratings yet

- Ho, Ho, Hoax The Case Against Santa ClausDocument29 pagesHo, Ho, Hoax The Case Against Santa ClausAria BarraleNo ratings yet

- Words of Wisdom (Mevlana Rumi)Document5 pagesWords of Wisdom (Mevlana Rumi)Jose MarinhoNo ratings yet

- Student Development TheoryDocument9 pagesStudent Development Theoryapi-326536311No ratings yet

- Various Interpretations of The Sexual UrgeDocument8 pagesVarious Interpretations of The Sexual UrgeJulian Raja ArockiarajNo ratings yet

- Dane Rudhyar - To Love or To Be in LoveDocument6 pagesDane Rudhyar - To Love or To Be in LovebosiokNo ratings yet

- Order by Jose Luis SoriaDocument13 pagesOrder by Jose Luis SoriaHesbon Moriasi100% (1)

- DuaDocument5 pagesDuaYusuf CarrimNo ratings yet

- Dhikr RewardDocument14 pagesDhikr Rewardjanaah786No ratings yet

- 2741417w16 MelvzDocument46 pages2741417w16 MelvzNivlem B Arerbag100% (1)

- Ethic CodeDocument3 pagesEthic CodeJayen Mareemootoo100% (1)

- Key Terminology (ETHICS)Document6 pagesKey Terminology (ETHICS)Apeksha SuranaNo ratings yet

- Epicurus' Letter To MenoeceusDocument3 pagesEpicurus' Letter To MenoeceusUnknownNo ratings yet

- Green: Positive Color Meanings in BusinessDocument4 pagesGreen: Positive Color Meanings in BusinessedersonNo ratings yet

- Summary: The Laws of Human Nature: by Robert Greene: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: The Laws of Human Nature: by Robert Greene: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (30)

- The Stoic Mindset: Living the Ten Principles of StoicismFrom EverandThe Stoic Mindset: Living the Ten Principles of StoicismRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (12)

- Stoicism: How to Use Stoic Philosophy to Find Inner Peace and HappinessFrom EverandStoicism: How to Use Stoic Philosophy to Find Inner Peace and HappinessRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (85)

- The Story of Philosophy: The Lives and Opinions of the Greater PhilosophersFrom EverandThe Story of Philosophy: The Lives and Opinions of the Greater PhilosophersNo ratings yet

- The Secret Teachings Of All Ages: AN ENCYCLOPEDIC OUTLINE OF MASONIC, HERMETIC, QABBALISTIC AND ROSICRUCIAN SYMBOLICAL PHILOSOPHYFrom EverandThe Secret Teachings Of All Ages: AN ENCYCLOPEDIC OUTLINE OF MASONIC, HERMETIC, QABBALISTIC AND ROSICRUCIAN SYMBOLICAL PHILOSOPHYRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- The Emperor's Handbook: A New Translation of The MeditationsFrom EverandThe Emperor's Handbook: A New Translation of The MeditationsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (10)

- How to Destroy America in Three Easy StepsFrom EverandHow to Destroy America in Three Easy StepsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (21)

- Stoicism The Art of Happiness: How the Stoic Philosophy Works, Living a Good Life, Finding Calm and Managing Your Emotions in a Turbulent World. New VersionFrom EverandStoicism The Art of Happiness: How the Stoic Philosophy Works, Living a Good Life, Finding Calm and Managing Your Emotions in a Turbulent World. New VersionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (51)

- How States Think: The Rationality of Foreign PolicyFrom EverandHow States Think: The Rationality of Foreign PolicyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (7)

- The Three Waves of Volunteers & The New EarthFrom EverandThe Three Waves of Volunteers & The New EarthRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (179)

- It's Easier Than You Think: The Buddhist Way to HappinessFrom EverandIt's Easier Than You Think: The Buddhist Way to HappinessRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (60)

- Knocking on Heaven's Door: How Physics and Scientific Thinking Illuminate the Universe and the Modern WorldFrom EverandKnocking on Heaven's Door: How Physics and Scientific Thinking Illuminate the Universe and the Modern WorldRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (64)

- 12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson - Book Summary: An Antidote to ChaosFrom Everand12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson - Book Summary: An Antidote to ChaosRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (207)

- Jungian Archetypes, Audio CourseFrom EverandJungian Archetypes, Audio CourseRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (124)

- This Is It: and Other Essays on Zen and Spiritual ExperienceFrom EverandThis Is It: and Other Essays on Zen and Spiritual ExperienceRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (94)

- The Authoritarian Moment: How the Left Weaponized America's Institutions Against DissentFrom EverandThe Authoritarian Moment: How the Left Weaponized America's Institutions Against DissentRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (17)

- Moral Tribes: Emotion, Reason, and the Gap Between Us and ThemFrom EverandMoral Tribes: Emotion, Reason, and the Gap Between Us and ThemRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (115)

- The Socrates Express: In Search of Life Lessons from Dead PhilosophersFrom EverandThe Socrates Express: In Search of Life Lessons from Dead PhilosophersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (79)

- Roman History 101: From Republic to EmpireFrom EverandRoman History 101: From Republic to EmpireRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (59)

- Summary of Man's Search for Meaning by Viktor E. FranklFrom EverandSummary of Man's Search for Meaning by Viktor E. FranklRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (101)