Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Picturing The City

Uploaded by

Shane ClarkOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Picturing The City

Uploaded by

Shane ClarkCopyright:

Available Formats

Childrens Geographies Vol. 8, No.

2, May 2010, 123 140

Picturing the city: young peoples representations of urban environments

Tine Benekera , Rickie Sandersb, Sirpa Tanic and Liz Taylord

Department of Human Geography and Planning, Faculty of Geosciences, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands; bDepartment of Geography and Urban Studies, Temple University, PhiladelphiaPA, USA; cDepartment of Teacher Education, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland; dFaculty of Education, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK

a

Urban environments form the setting of everyday life for most Western young people. This article explores visual representations of cities made by young people in a range of environments within four countries. The ndings inform a larger study on urban geographies within geography education. We analyse students drawings of cities regarding physical characteristics, activities and issues. There are many commonalities between drawings from the four countries, the majority showing a big, busy city representation with skylines, trafc and shopping areas. There are also distinctive characteristics for each set, for example Finnish students tended to emphasise environmental and social issues more than in the other countries. In relation to methodology, we conclude that drawings, supported by contextual information, are a useful source to understand young peoples representations of cities. Further, this research supports thinking about how to merge young peoples experiences and imaginaries with the teaching of urban geography. Keywords: city; young people; visual methods; geography education

Introduction Urban environments are the settings for everyday life for most Western young people, and young peoples experiences of the city have formed the focus of a wide range of academic work (McKendrick 2000). This research project arose from an interest in the extent to which young peoples urban experiences are addressed in their geography education in school. Does their education help them understand the place they live in and draw on their existing experiences? If not, how could teaching about urban areas be developed in the future? In the rst stage of the project, we researched current teaching on cities in the four countries in which we work: England, Finland, the Netherlands and the USA. We compared four different perspectives on learning about urban geographies. We started by using content analysis to examine representations of urban geography in the curricula and selected textbooks for younger secondary school students, choosing this age group because geography is a compulsory part of their education. These rst two sources gave us a feel for the statutory curriculum at the time, and its mediation by textbook authors, frequently a strong inuence on classroom practice. Teachers views on the teaching of urban geographies, and their current practices, were then

Department of Human Geography and Planning, Faculty of Geosciences, Utrecht University, Postbox 80115, 3508TC Utrecht, The Netherlands. Email: t.beneker@geo.uu.nl ISSN 1473-3285 print/ISSN 1473-3277 online # 2010 Taylor & Francis DOI: 10.1080/14733281003691384 http://www.informaworld.com

124

T. Beneker et al.

elicited through questionnaires. Finally, for this stage of the project, we asked a selection of cultural and urban geographers to indicate key developments in urban geographies and to suggest how these might be used in a school context. Although, as would be expected, there were differences in the organisation of the curriculum within the four countries, and some curricula were more prescriptive than others, there were some commonalities. In particular, the interpretation of the curriculum by the textbooks resulted in a focus on built environment and urban functions, with a tendency to highlight negative aspects of urban life, such as congestion or housing issues (Beneker et al. 2007). The scale on which the city was discussed tended to be local or regional, often treating the city as a discrete unit, isolated from its rural surroundings or global context. When the geography teachers were asked for their views on the importance of selected urban geography topics, they highlighted urban planning, urban change, urban structure and social issues as most important for their students to learn about. For the most part, they conrmed the importance of topics which they were already teaching. However, the urban and cultural geographers, taken together, had a broader view of the city, involving a greater emphasis on issues of politics and social justice and the place of cities within a broader web of spatial interrelationships and processes. Their contributions suggested interesting themes to pursue within an educational context, such as understanding the global through the urban local and exploring the socio-cultural diversity of urban population. With ideas from these four perspectives in hand, the second phase of the project was to investigate the images and ideas of young people about the urban and urban geographies. This article focuses on their perspective. We explored young peoples representations of urban areas, how they use the city, what interests them about urban areas and what aspects they would like to learn about in geography. We will give particular emphasis, here, to the visual representations of cities which students made as part of that research. We consider the meaning of young peoples lived spaces, their personal images of different environments and their possible stereotyped and mediated images. We will pay special attention to their ideas of the urban environment; the characteristics of a city for them; the kinds of images they connect with cities and whether there is any kind of connection between their overall ideas of cities and their own urban environments. Is it possible to recognise mediated images (from education, TV, newspapers, etc.) within their visualisations? We will also explore distinguishing characteristics, comparisons and contrasts between the representations made within the four countries. Our ndings will be analysed by concentrating on three aspects of the drawings: the physical features of cities, the activities that young people attached to urban environments and, thirdly, the different types of issues connected to urban spaces. These discussions will be illustrated by an in-depth consideration of case studies from each country. Our results raise some questions regarding the challenges of visual methodologies and international research projects, but they also show some interesting aspects of urban living, relations to cities and differences in teaching about urban issues in our countries. Young peoples experiences of cities How young people think of cities and why they do so, is a result of a complex process of mental representation. The mental image of a city is a product of the attempt to process large amounts of information (Kotler et al. 1993). This information comes from both direct experiences and indirectly through mediated images (Matthews 1992, Aspeslagh et al. 2000, Ono 2003). Childrens and young peoples relations with their environment have been a popular topic of research both in childrens geographies and environmental psychology. Throughout this work, cities are still often seen as the opposite to nature, particularly Arcadian notions of nature. Nature has been regarded as an important place for playing (see, for example, Hart 1979,

Childrens Geographies

125

Moore 1986) and its meaning for childrens affective and intellectual development has also been recognised (e.g. Kahn and Kellert 2002). Korpela (2001) has studied Finnish peoples favourite places and, according to him, a majority of the respondents mentioned green spaces or natural environments as their favourites even when they lived in cities. When nature and countryside have been regarded as positive childhood environments, the city has often connected with problems and its effect on childrens later life has been a subject of concern (for more about this discussion, see Nairn et al. 2003, p. 14). In their summary of environmental psychology research on children and the city, Spencer and Woolley (2000) point to the public debate and the parental concern regarding the city as a dangerous arena for children. Rissotto and Giuliani (2006) have stated that the increase of trafc, the reduced number of public spaces and the declining sense of community have caused dehumanisation of urban space which has particularly affected children, whose possibilities to free mobility has diminished (see also Christensen 2003). Attention has been paid to the importance of spending time without adults guidance and surveillance in outdoor contexts, whether in natural, rural or urban environments (Crowe and Bradford 2006). Childrens capability to take possession of their space; to play, to communicate with each other or just to spend time, to hang around in public space, has been stated as important (see, for example, Christensen 2003, Nairn et al. 2003, Thomson and Philo 2004) but, in some studies it has been noted how public space has been transformed from a space that belongs to children into a space where children are only accompanying the adults (Karsten 2005). Many researchers have noticed the decrease of childrens independent mobility in urban public spaces (for example OBrien et al. 2000, Karsten 2005, Rissotto and Giuliani 2006) and raised a concern about its possibility to decrease their knowledge of their local environments. At the same time, many surveys bring evidence that children have a great environmental awareness and concern (Alerby 2000, Spencer and Woolley 2000). According to Spencer and Woolley (2000, p. 189), this concern is often characterized with anger and frustration about the apparent indifference and poor stewardship of adults. They are convinced that these views are not (just) a repetition of mediated images, but grounded in childrens own local experiences (in Britain). Skelton and Valentine (1998) in their exploration of the experiences of contemporary youth in various cities across the world explore issues of resistance, representation, and geographical concepts of scale and place. Their edited volume reveals that youth actively resist stereotypes and challenge the ways that adults seek to dene their lives. In fact, they deliberately seek ways to create their own independent representations of their lives. Similarly, Wridt (2006) in her work with young people in Denver CO, where they were asked to create maps of their neighbourhoods, found that students have real and unmediated experiences of neighbourhoods around their school, the places they play, the places they get food, and even the bad places. In studies of children and young people occupying public spaces, the city as a setting has become the most analysed environment (see, for example, OBrien et al. 2000, Nairn et al. 2003). For example, one public debate regarding young people and urban environments concerns the enormous commercial attention that has been given to childrens role as consumers, especially in new plazas and malls (Spencer and Woolley 2000). The role of children as consumers in the local economy and their use of public spaces, malls and plazas often seems to be presented in the media as if children were inevitably socially problematic and in conict with adult users. Uzzell (1995, see also Matthews et al. 2000) showed that users of malls in British towns do not regard them as places to shop but rather as social places which may satisfy various physical, social and psychological needs. Love Park in Philadelphia, widely known throughout the skateboarding community as a place that challenges even the best boarders, is also a lunchtime retreat for city workers. Its reappropriation by youth on skateboards prompted city government to prohibit the use of the space.

126

T. Beneker et al.

Simplifying dichotomies between the rural as backwardness, tranquillity and simplicity and the urban as progress, vibrancy and complexity have led to the idealisation of the rural. There are, however, increasing number of studies where this kind of dichotomous thinking has been avoided and the city has been seen as an important and normal setting for children and young people (for example Cele 2006). Stereotyped images of city and country have been challenged and new aspects for studies of children environment relations have been introduced in more complex and nuanced ways for example by Nairn et al. (2003). A more focused treatment of suburban landscapes would offer additional insights.

Mediated images of cities The inuence of the media culture on young peoples representations of place is well documented (for example, Matthews 1992, Holloway and Valentine 2000, Taylor 2007). The view of cities presented in news media can focus primarily on negative events such as crime, violence and social problems sometimes ignoring positive events and developments (Van Ginneken 1998, Avraham 2000, 2004). These images are important because they affect perceptions and spatial decisions of the general public and inhabitants in particular places (Avraham 2004). Even if young people do not read newspapers or watch the TV news themselves, other inuential people in their environment will (for example parents or teachers) and these perceptions are passed on. Of course not all cities are represented in the same negative way. There is a difference in the nature and quantity of the representation. In general, larger cities receive more attention, resulting in a richer image, compared to smaller cities which receive less attention and a more one dimensional image. Avraham (2004) illustrates this for Israel where the majority of news coverage of peripheral development towns in national newspapers were about crime and trials, living problems and accidents and disasters. Crime alone counted for 37% of the news items about development towns in total and for 17% of the coverage of larger cities, such as Tel Aviv. Knox and Pinch (2000) suggest that imaginings about the city rely on metaphors use of a word or phrase to describe by referring to another thing not literally appropriate, e.g. urban jungle. They identify several metaphors used to describe the city. Overwhelmingly, these metaphors contain negative or dystopian imagery (Knox and Pinch 2000):

Metaphor Babel Market Theme park Jungle Labyrinth Melting Pot Hell Babylon Connotation/example a cacophony of non-communicating voices a place where goods and services are bought and sold a place of fantasy, spectacle and excitement a dangerous and threatening place where some people do not survive a confusing place from which there is no escape a creative place in which diverse groups mix together a nightmarish place of punishment a place of luxury and afuence alongside vice, corruption, and tyranny

The negative image of urban areas is also reinforced in lms and television series where cities are the most important background to crime or subversive cultures (for example CSI, The Wire, or The Fast and the Furious: Tokyo Drift). In addition, the urban dystopia is a common setting for science ction or other futuristic genres (Crang 1998). This can be seen in lms such as the Terminator sequence, or the classic Blade Runner. Of course, not all representations of the city in popular culture are negative lms such as Notting Hill, the recently released American lm Crash, or the TV series Friends, foreground the city as a space for the development of new forms

Childrens Geographies

127

of community. Views of the city from some media have shaped the iconic status of some urban landscapes, such as the view of the New York skyline in Friends or the aerial view of the meander in the River Thames shown at the start of the UK soap Eastenders. Thus, in general, the mediated images of cities that reach young people have a tendency towards urban problems, sometimes with a highly negative undertone in news media. The power of these representations was evident in some of the responses by students. Methodology To develop our understanding of students experiences and representations of cities, we asked selected classes to complete a Cities quiz, a four-sided folded A3 booklet, based on a method used by Taylor (2009). Activities in the booklet included a word association task (noting words or phrases which students associated with cities), drawing a view out of a window in a city and writing a postcard describing a city they knew (with accompanying picture). There were also some short questions regarding students views about the city, its use by different people, their thoughts on learning about cities in geography and nally some questions about the sources of students ideas. In addition to these main questions, we asked for some background information (students gender, age, home location). The quiz was translated from English into Dutch and Finnish. An advantage of this method was that it gave students the opportunity to represent cities through a number of different activities and through both written and visual modes. This gives a richer representation than any one task alone. The rst two tasks were designed to generate rst impression of cities, possibly therefore a more generic response, whilst later tasks focused on direct experience of actual cities. Ideally, the quiz would also be combined with one-to-one discussion with the researcher, either during or after completion of the quiz. This would allow for clarication of any less obvious aspects of the drawings and elicitation of more detailed information regarding sources, as well as ensuring those students who felt more comfortable with verbal than written interaction were able to communicate their ideas. In addition, it might have enabled us to establish causality between elements of the data which seem to be interrelated, as discussed later in this article. However, with the volume of students involved, such interaction was not possible within the constraints of this project. As we had a particular interest in young peoples direct experience of urban areas, we chose schools from urban surroundings to which we had access to be part of the case studies. More detailed information on the characteristics of the case study schools is given in Table 1. As we were initially interested in the differences in representations between students whose schools were in the city centre and those in more suburban areas, this inuenced our choice of schools. However, we later realised that the patterns of urban land use and types of residential areas in the different countries were diverse and hard to interpret. Therefore we decided not to make any straightforward interpretations of the possible differences between the city centre and suburban schools. In addition, not all students lived close to their school (see Table 1 for information about home locations). Within the schools, we aimed for students with a mixture of ages and attainment levels to complete the cities quiz. For the most part, this selection was made by the teachers through whom we negotiated access, and who presented the quizzes to their classes, using a set of common guidelines, including a brief explanation of the purpose of the activity. All of the students enrolled in the class participated in the exercise and, in general, completed the entire booklet. Students were asked to work on their own to complete the task, and there was no whole class discussion, though the possibility of neighbours comparing their work cannot be discounted. The students were asked to complete all sections of the quiz, though a small number chose not to do so. We are aware of the problems of straight-forward generalisations from the data and we will be careful to avoid these but, building on our earlier ndings (Beneker et al. 2007), we were also

128

T. Beneker et al. Main characteristics of the participants and data generated.

Types of school areas Students ages 11 14 City quizzes completed1 128 (128 drawings of view from window) 181 (173 drawings)

Table 1.

England

Finland

The Netherlands

USA

2 schools from Peterborough; one inner city, the other suburban. Students home locations: 58% city, 42% village/town/other 3 schools from Helsinki, one from the city centre and two from different suburban areas. Students home locations: 94% city, 6% village/town/other 2 schools, one from the city centre of Rotterdam and the other one from a suburban location. Students home locations: 84% city, 16% village/town/other. 3 schools, one from Denver (CO), one from Silver Spring (MD) and one from Philadelphia (PA). Students home locations: 81% city, 19% village/town/other.

13 15

12 16

156 (151 drawings)

11 17

72 (72 drawings)

Numbers of drawings completed shown in brackets. A small number of students chose not to make a drawing.

interested in taking a closer look at the possible differences in the representations between countries. The main focus of this article is the visual data of the students drawings of cities. Almost all of these drawings were made in pencil, with a few in pen. Only a small proportion (4%) made use of colour. Accordingly an analysis of the difference between drawings in black-and-white versus those in colour is not possible.1 In analysing the drawings, we followed a method used for the analysis of photographs by the anthropologists Collier and Collier (1986, pp. 178 179). This rigorous approach starts with a holistic view of the dataset, in which general thoughts, questions and impressions are noted, then proceeds to a detailed analysis of pertinent characteristics image by image, concluding with another holistic view. The entire set of drawings was rst analysed by Tani and Taylor in August 2007. Following Collier and Colliers general approach, we took the set of pictures for each country at a time and laid out all the sheets with the rst page up, school by school. Then we looked at them all to get an overview, noting down our general impressions, questions and interesting examples. We then compared those ideas and showed each other items of interest which we had noted. At this point we identied three themes which had stood out to both of us from the drawings: (1) depiction of social issues, such as crime, violence or terrorism and drug or alcohol abuse; (2) environmental issues, such as vehicle and factory pollution; and (3) depiction of open/green spaces such as parks, forests and childrens play areas. In Sanders analysis of the US data, another theme that rose to the surface was specic characteristics ascribed to people who live in the city, making specic note of rude, crazy, angry facial expressions, loud, and tourists. Next, during a stage of detailed focus, we reviewed the form of the built environment and types of transport represented country by country and by school. In addition, each researcher collected all the questionnaires which they felt showed an instance of the three issues identied above (and the debatable ones). After that, we cross-checked the ones the other had left. We found this checking very useful because we had to think carefully through our classications. We recorded instances of the issues in detail, also noting links between different issues (for example crime and drug abuse together on one drawing). We also recorded school and age for each instance to get a feel for the pattern of which students were drawing these things. Then we discussed general ndings and noted any particularly interesting/typical drawings for future use. In the small number of instances where the meaning of elements of a drawing was unclear (for example, whether a squiggle was a tree or smoke) it was helpful to refer to other answers for that student to gauge the context. Summary data was collated into Excel.

Childrens Geographies

129

In the second phase of the detailed analysis, we explored whether there was a relationship in the data between the students home locations within the city and the features of their drawings. This process worked well for data from the UK and the Netherlands, but this division between different categories of urban area did not work for Finland or the US. In Finland there were differences in the form of the Finnish city; Finnish suburbs can not be compared with the English or Dutch ones. In the US, students could not be asked to provide their home addresses because of condentiality constraints. In the third phase, we compared the drawings in question two of the quiz (view out of a window in a city) and those from question three (postcard of a particular city students knew). The Dutch drawings were harder for us to interpret due to language issues and we felt that some landmarks could have been missed, due to our less developed knowledge of the cities concerned. Finally, we returned to a consideration of the bigger picture shown in the data. In June 2008, the analysis continued when Beneker and Tani considered the Dutch data in detail and compared it with the previous results from England and Finland. Sanders later conducted a similar investigation of the US data, including the postcard images. In the following sections, we will outline three aspects of our ndings. First, we will give an overview of the physical environments that the students represented as cities. We use ndings from the USA to shed light on this aspect of our ndings. Secondly, we will consider the activities which were depicted as occurring within cities. Analysis of student data from Rotterdam allows us to explore this theme. Thirdly, we will concentrate on different types of issues that were represented in the students drawings and use Finnish data as a case study. Thus, the three case studies with particular examples of students representations illustrate the more general points. What physical environments were associated with cities? In question two of the quiz (drawing a city); we aimed to elicit students rst impressions of cities. In each country, the representation of the city as a place of at least some high-rise buildings was very common (Table 2). Some young people drew pictures solely of urban skylines, or their drawing was dominated by high-rise ofce buildings and large apartments. It was not a surprise that American young people had high-rise buildings in their drawings more often than those from Europe, but their high incidence in the Finnish drawings surprised us. It is impossible to give any rm explanations of this result, but one possible reason could be that houses are usual in English and Dutch cityscapes, whereas in Finnish culture, cities are often thought to mean big buildings, even if many of the urban neighbourhoods are areas for detached houses and terrace houses. Many drawings showed street-level fragments of a city centre, often shopping streets. These pictures included a mixture of high-rise buildings and houses, some showing close-ups of particular features, such as a playground, a house, people, or a tower. Many in the US sample included names of specic shops Starbucks, McDonalds, Borders, the Gallery (a large mall in Center City Philadelphia), etc. Others showed features that spoke to scale, Table 2. Incidence of key features of the urban environment in students drawings.

Drawings with high-rise buildings England (128) Finland (173) The Netherlands (151) US (72) 67% 81% 72% 88% Drawings with open or green space 29% 38% 32% 21% Drawings without people 60% 53% 78% 75%

130

T. Beneker et al.

density, and diversity trafc scenes, streets crowded with people and cars, skyscrapers, and apartment complexes. Although in many cases, the urban landscape was dominated by buildings and street scenes, 21 38% of drawings also included open or green space (Table 2), perhaps indicating the way children use urban environments in their everyday lives (Cele 2006). A few depicted the city as a cheerful place with bright sunshine, clouds, birds, and trees set alongside skyscrapers and high rise buildings. Prevalence of drawings with open or green space varied between the countries, but the differences were not very clear. In Finnish drawings there were more parks and open space than in other drawings. Even some forests and summer cottages by the lake were included in the Finnish pictures of urban environments (Figure 1). It was interesting that the majority of drawings of the city did not include people (Table 2). This was particularly noticeable in the English, American and Dutch pictures. Wide, empty roads and broad highways were surprisingly common in Dutch drawings, and many young people living in Rotterdam drew urban landscapes with water (River Meuse). Similarly street scenes with cars were common in the US. By using our knowledge of landmarks, we were able to identify some drawings as representations of actual cities. Helsinki, Peterborough and Rotterdam, where the schools were located, were quite often present in the drawings, but there were also pictures where London, Paris, Philadelphia, and New York were easy to recognise. So, for example, pictures of London, including landmarks such as Big Ben or the Millennium Wheel, were drawn by the students from Peterborough (see Figure 2). Landmarks from Rotterdam included: the Feyenoord Stadium (De Kuip), the Erasmus Bridge (bridges north and south of the city across the Meuse) and the Euromast, from where you can view the city. Landmarks from the US included Love Park (famous as a site for skateboarding); the Empire State Building in New York City, and majestic snow capped mountains in Denver. In terms of mediated images, one example from the English drawings was a depiction of the destruction of the Twin Towers; reecting images very prominent on TV news (see Figure 3).

Figure 1. Drawing by a 14-year-old girl living in a new urban area near the centre of Helsinki, Finland. Some of the Finnish drawings portrayed the city as a combination of both urban and rural elements. In this example, a busy city life is connected to the view from the countryside: a summer cottage by the lake and forest can be seen on the top left corner of the picture.

Childrens Geographies

131

Figure 2. Drawing showing London landmarks by an 11-year-old girl from Peterborough, England. Earlier in the quiz, she reported that she had visited London, Texas and Indianapolis. Many drawings did not have any clear resemblance to any specic city but they were pictures of imagined cities showing some ideas of the city as a phenomenon, quite often a skyline of a big city. When we asked students about their sources of ideas, later in the quiz, there was some variation between the four countries, but both direct experience (living in a city, visiting cities) and indirect experience (internet, TV/radio news) were cited as important. When students were asked to draw a postcard from a particular city they knew, at a later point in the quiz, students were more precise in their reference to actual places. For example, in the Dutch postcards, Rotterdam and especially the city centre was drawn. If students had already drawn Rotterdam in the rst picture, they referred to it, or made a picture with more detail by zooming in on the soccer stadium, a particular shop, street or open space. A few made a picture of a city visited during holidays, such as Willemstad (Curacao), Venice, Chiang Mai (Thailand).

Case study: US scale and personality Drawings from students in three different urban areas in the US, each differing in terms of population size, diversity and geographical location, provided a rich database from which to glean information about the image that youth hold of the city and how the youth in each of the three distinct urban areas view the city. While much has been written about the inuence of the media and popular culture, it is not entirely clear from these data whether the negative images or anxieties the youth express are the result of personal experience or media images. Both were cited as important by the American young people (73% put living in a city as a source, 71% visiting cities yourself and 64% TV/ radio news, though only 45% TV programmes/lms). What does stand out in the drawings of US youth is the attention to scale, density, diversity (e.g. big events, big streets, excessive houses, crowded, high crime, lots of trafc, and different kinds of people). Of note also is the importance of the personality characteristics of the people in cities represented in some drawings (e.g. loud, rude, cracked-out places where people lose their minds, crazy, and angry facial expressions). Interestingly, the latter do not seem to be common themes in the data from

132

T. Beneker et al.

Figure 3. Drawing of New York, showing evidence of media coverage of the destruction of the Twin Towers (by an 11-year-old boy living in a village near Peterborough, England. He had seen a TV programme or lm about 9/11 and knew someone who had visited New York, though he had not been himself). Finland, the Netherlands, and England. Figure 4 with its image of city centre Philadelphia also contains a crane. At a minimum this suggests an awareness of change and growth in the city. Also of note among youth in the US drawings was the attention given to the classic elements of the city identied in the work of Lynch (1960) paths (street scenes), nodes (intersections of streets, transitions and breakpoints from transportation), districts (areas which have a common character, which are recognised internally and externally and which the observer can go inside), and nally landmarks (simple physical elements that are point references).

Figure 4. Icons of downtown Philadelphia (by a male student living in that city, no age given).

Childrens Geographies

133

The supplementary information on the quizzes showed that American students used the city for shopping, fun, and doing cool things. While they think of the cities in which they live in different ways, there are common themes. The dominance of the city as big was an idea expressed in their views of cities as places. In designing a postcard from a city they go to, most students included iconic representations of their own city Denver with its backdrop of snow capped mountains, Philadelphia with its vibrant changing and growing city centre, and Silver Spring Maryland with its malls.

What activities were associated with cities? In addition to physical features presented in the drawings, we were interested in analysing functions and activities which the students attached to their urban images. When we looked closer at the high-rise buildings, a lot of them did not show their primary use, and on this point it would have been useful to have been able to talk to the students about their drawings. There were also houses in the pictures, more suburban style in the US ones, and typical Dutch, English or Finnish houses (see Table 3). So, living is one aspect of the cities which is easy to nd in the pictures. Another obvious function concerned different types of transport. Sixty four per cent of the Finnish students had included some cars in their drawings, while they were less usual in Dutch, English and American drawings. This seems to be surprising, when the importance of private cars, especially in American cities, is considered. There was also more public transport than elsewhere in Finnish drawings. In English pictures, there was more variety in types of transportation (planes, lorries, helicopters, buses, in addition to cars) than in other countries. Shopping is also one aspect which was heavily connected to the urban images. All kinds of shops were evident, including many internationally known brands (for example clothing shop H&M can be seen in Figures 1 and 5), also national chains. In the American drawings there were somewhat fewer shops than in the European cities. This may be surprising, but one possible reason for it could be that shopping streets are not as important as in European cities. Maybe popularity of malls in American cities and suburbs make shops more invisible in cityscapes compared to European ones. There was also fairly signicant representation of restaurants in the pictures. Most often the named ones referred to multinational corporations, hamburger chains especially. The pictures did not include schools and only a few ofces (the latter often related to exceptional buildings or landmarks which were headquarters). Interestingly, in English drawings, evidence of religious activities (seven churches, a mosque and a synagogue) was more common compared with the situation in the Dutch, Finnish or American drawings.

Case study: Rotterdam landscapes of consumption Many (58) drawings from young people in Rotterdam show us landscapes of consumption (see, for example, Figure 5). This is not surprising if we accept that cities have become more and more Table 3. Presence of various urban activities in the drawings.

Drawings with houses England (128) Finland (173) Netherlands (151) US (72) 38% 9% 30% 19% Drawings with shops 45% 39% 36% 11% Drawings with cars 59% 64% 30% 42%

134

T. Beneker et al.

Figure 5. City as a landscape of consumption (by a 14-year old female student from Rotterdam, the Netherlands. She commented on Rotterdam: Very nice, a lot of choice, especially clothing, and very cosy, very busy, and open every Sunday). a place of consumption. As Burgers (2000) says, the city can be seen as a site of enticement and temptation. Identity is more and more expressed in lifestyle and consumption patterns. Urban facilities have become a gathering place for every social group and urban public space has an important role in the romance market (Burgers 2000). The landscapes of consumption include shops, often fashion shops, cinemas or theatres, and well known shopping streets in the city centre. The shops frequently include signs showing brand names and sometimes with sale 30%/50%. Several drawings are very specic on the location and juxtaposition of shops. In total, 115 shops are mentioned, a lot of them more than twice. The majority of the shops mentioned are fashion shops (61), and the Swedish Hennes & Mauritz (H&M) is most mentioned, 16 times. The shops include international designer fashion brands such as Dolce & Gabbana, Gucci, Bjorn Borg, Tommy Hilger, Esprit, Ralph Lauren and La Coste. Other types of shops are pharmacies (11 shops), such as Douglas, Etos and Chanel. Three warehouses, HEMA, V&D and Bijenkorf (all Dutch) are mentioned 13 times. Besides shops we see popular international brands of eating places: particularly McDonalds (more than 10 times), and a few times Burger King, Kentucky Fried Chicken, as well as other generic labels such as restaurant. Many times the cinema, Pathe, is shown. Some brands are shown as signs on big ofce buildings: Coca Cola, Shell, ING-bank and another Dutch insurance company (Nationale Nederlanden). By far the majority of all the brands and shops mentioned are international. To give additional context to these drawings, in another question on the quiz, students were asked how they used the city themselves and how they felt about it. Within the Dutch responses, almost 100% of young people said that the city is used for shopping and they like it. Rotterdam has, in their eyes, enormous opportunities for looking around and buying things (clothes, games) in the main shopping area in the city centre. Shops there are open seven days a week and there are often musicians in the streets. Another thing mentioned regularly is going to the cinema and eating in restaurants. Some added hanging around, chilling, and skating. There was no clear difference in replies between boys and girls. Girls wrote that they go shopping with their mother or with friends. One boy said: I go shopping, that means walking behind my mother and sister! In the answer to another question, in which young people were asked to suggest

Childrens Geographies

135

the most beautiful spot in the city, boys responses indicate another activity; they like the soccer stadium of Feyenoord and enjoy going there. The majority of young peoples answers regarding what they dislike is that it often is too busy in the shopping area, with too many people in the shops and on the streets. What issues were connected with cities? As we proceeded with our analysis of the whole dataset, we concentrated on different types of issues which seemed to step out from the pictures. First, we noticed there were lots of problems connected to urban environments and therefore, we decided to take a closer look at them. We identied two main types of problems: some depicted social issues while the others were representing environmental concern. Some drawings had examples of both of these types. We will analyse these issues in more detail in the following section. Social issues Overall, social problems were not that common in drawings: their incidence varied between 4% (the Netherlands and the USA) and 16% (Finland) (see Table 4). Crime (violence) was the only (but still rare) social problem present in the American drawings; only three drawings showed some indication of it. The situation was quite similar in the Dutch drawings, and the English ones also seldom showed any social issues. What was striking was the amount of social problems represented in Finnish drawings compared to other countries. There was more evidence of crime, violence and drugs in Finnish pictures than in other countries, and 12% of the Finnish drawings showed issues of alcohol abuse, which was not evident on drawings from the other countries. It is interesting to note that when citing sources for their ideas, the Finnish students gave greater prominence to TV programmes and lms than students from the other three countries. However, further research would be necessary before any causality could be established between these ndings. Terrorism was portrayed in two pictures in Finland, England and the Netherlands, but it was not depicted at all in the American drawings. Environmental issues Environmental issues were more common in the drawings than social ones. Almost every third Finnish drawing had some kind of reference to environmental issues (see Table 5). They were also relatively common in the English drawings, but not so much in the Dutch or American ones. It is difcult to give any certain reason for these differences: is it because of the differences in environmental awareness or does it have something to do with the way cities are used to think as places of environmental problems? For example, it is possible that the urban environmental problems such as vehicle pollution described in geography textbooks are an important inuence on students representations. In this regard, it is interesting to note that books and magazines are Table 4. Social issues portrayed in the drawings

England Total drawings Alcoholism Crime/Violence Drug abuse Terrorism 8% (6) 0% (0) 4% (6) ,1% (1) ,1% (2) Finland 16% (27) 12% (21) 6% (10) 6% (10) 1% (2) The Netherlands 4% (6) 0% (0) 3% (4) 1% (2) 1% (2) USA 4% (3) 0% (0) 4% (3) 0% (0) 0% (0)

136

T. Beneker et al. Environmental issues portrayed in the drawings.

England Finland 31% (53) 9% (16) 12% (21) The Netherlands 14% (21) 4% (6) 4% (6) USA 10% (7) 3% (2) 4% (3)

Table 5.

Total drawings Signicant vehicle pollution Signicant chimney pollution

23% (29) 6% (8) 10% (13)

cited as a source of ideas about cities by a much higher proportion of the Finnish students than the other three countries (70% compared to 40 52%). School is also cited as a source more by the Finnish students (53% compared to 26 44%). However, again, it is not possible to be condent of a causal link from the available data. In general the Rotterdam pictures give a reasonably positive impression. In the added comments, a lot of the teenagers state that they are proud of the city. Case study: Helsinki landscapes of social and environmental problems The Finnish drawings seemed to tell a different story compared to other countries and therefore we wanted to pay special attention to the pictures where social and/or environmental issues were presented. We counted all the pictures showing any traces of exhaust gas or smoke from the factories, both signicant and slight pollution. A total of 24% of the drawings showed polluting vehicles while 21% had some factory pipes with fumes (Figure 6). There were some differences between the drawings from the different schools; the school in the eastern suburb having fewer environmental problems presented than the two other schools. Based on these results, the Finnish students seem to think of the city as a place of environmental problems. Social problems were also mentioned relatively frequently in the Finnish results. There was a big difference between the two suburban schools: 25% of the students in the eastern suburb depicted some social issues in their drawings, while only 9% of the students in the other suburban school mentioned social problems. Results from the city centre school were between these

Figure 6. Environmental problems, for example vehicle pollution, were often portrayed in Finnish drawings (this one by a 15-year-old-girl living in an area near the edge of Helsinki. Pakokaasua means exhaust gas in Finnish).

Childrens Geographies

137

two extremes. It is difcult to give any rm explanation for these differences, but there are some factors which could make the result more understandable. The school in the eastern part of the city is located in the area which was built in the early 1990s. It has a multicultural population with a high proportion of social housing. The neighbourhood has a bad reputation although its reality does not differ much from other parts of the city. However, residents experiences of insecurity are quite high there (Tuominen 2007, p. 16). What is interesting is the fact that these students living in this eastern suburb did not draw as many environmental issues as the students from the other areas. The Finnish drawings differed clearly from the pictures coming from other countries. This observation gives us an interesting example of the challenges of interpretation of visual representations and their relation to the reality. Finland does not have more environmental problems than the Netherlands, England or the USA, neither are its social problems any bigger. One possible interpretation could relate to a short history of urban culture in Finland, which can be seen in the ways how cities are thought as locations of crime, violence and pollution (see, for example, Beneker et al. 2007). Conclusion To conclude, we will rst summarise our ndings regarding students representations of the city as seen in the four sets of drawings, with particular regard to mediated images. Secondly, we will make some observations regarding our use of visual methods and the challenges of international research in this project. Finally we will consider some wider implications of our ndings, particularly as regards geography education. One feature of the dataset was the overall degree of similarity between the city drawings from the four countries, for example the incidence of high rise buildings, skylines, roads, trafc, and the big, busy city representation. When asked to draw a view out of a window in a city, four themes emerged. Many students responded with mediated or stereotyped images, rather than actual representations of the place they live or actual cities in their country. The incidence of high rise skylines suggests the inuence of media, rather than local experience, especially in Finland. When students do draw on their own experiences of local landmarks, for example to represent Rotterdam or London, the buildings were shown larger than life, perhaps dramatising their perceived importance. Overall, negative images of the city are recognisable, in terms of environmental and social issues, such as congestion and crime, but only in a minority of the images. Positive connotations can be widely found in the parks, green spaces (leisure activities), beautiful/interesting buildings (landmarks) and shopping areas. There is evidence of experience and daily life, particularly landscapes of consumption, also playgrounds or open spaces. In this way, the young people seem to be representing cities as somewhere for recreation (shopping, sports, eating, and entertainment) rather than education no schools were included in the drawings. Content from geography education (identied in our earlier work), such as urban form, can be recognised at a basic level, but not in more detail. For example, different parts of cities, in terms of a map or layers in the city are sometimes evident. Often the city centre/central business district is the object of the drawing rather than residential neighbourhoods, business parks or other areas. A range of functions of cities are evident, for example trafc/transport, shopping districts and houses/ofces, but these may be linked to everyday life as much as to representations from textbooks. Although the similarities between drawings from different countries were striking, there are also interesting differences between work from the four countries (as well as diversity within each set of drawings). We can tentatively suggest small differences between US and European cities: in the US set, there are even more high-rise buildings and fewer shops/shopping streets in

138

T. Beneker et al.

city centres. The Finnish drawings seem to have a greater degree of media inuence, especially compared to real Finnish cities, having a particular incidence of high rise buildings, a lot of trafc, and more social/environmental problems. Traditionally, nature and countryside have been regarded as normal environments in Finnish culture, which may also affect young people and their ideas of cities as something else, a place of problems. Regarding our use of visual methods within this project, the two opportunities for young people to draw on the quiz were designed to have complementary functions; the rst to elicit an initial response and the second to relate to young peoples views of a city they had visited. Placing this component of our research in the larger theoretical context of visual studies, it has been noted that in contemporary society, our values, opinions, experiences, ideas, and beliefs are more and more shaped by images and the visual culture they reside in. Thus, here we are concerned to unearth how young people make meaning and sense of their world what images do they rely on, foster, and negotiate. Most of the work in visual studies has relied on the study of popular forms of visual media television, advertisements, computer graphics, photography, movies, and works of art. Here, we rely on childrens drawings, their actual representations. Cultural theorist, Stuart Hall (1997) notes that it is the participants (in this case youth) in a culture who give meaning to the world. Indeed, it is by our use of things and how we represent them that we give them a meaning. Whilst it was useful to have two drawings for most students, the division of functions was not as clear cut as we expected the rst set included detailed depictions of known areas as well as more stereotyped or prototype images. In general, the level of care and detail spent on the drawings was high, but it may be that certain aspects of city life are less easy to depict in a visual form; perhaps it is easier to show environmental issues (such as vehicle exhaust pollution) rather than social issues, though certain students depicted issues of violence with some skill! In addition, typical drawing conventions have to be taken into account, for example cars are often drawn with exhaust fumes, so a small cloud of smoke cannot necessarily be taken as evidence that the young person was aiming to indicate air pollution issues. It is important to recognise the types of information for which drawings are a useful source; they were helpful to indicate students overall representations of the city, but it was more difcult to learn for certain about young peoples experiences in cities from this source, and additional information was needed from later in the quizzes. For example, a drawing including many shops suggests that shopping is an important part of that students urban experiences. However, additional comments are needed from that student to understand for certain how they use the city. Ideally, it would have been useful to talk to the students whilst they were drawing their pictures, but this would have entailed a much smaller dataset. Of course, within a classroom setting, there is always the possibility that students observed the work of their neighbour, so a joint representation resulted. However, many images were quite idiosyncratic in their depiction of detail, so this does not seem to have been a widespread issue. In terms of international collaboration, it was important that all members of the team were involved in the interpretation of the drawings, as it was necessary to understand the urban contexts of the students, for example in order to spot local landmarks. The ideal would have been one period of analysis with all group members present, enabling a shared decision-making process; however, the costs of transport for this small research project did not make this possible. Even with the staged process of analysis, the act of comparing images from the different countries helped us recognise distinctive characteristics of the data within each participants country as well as common elements. So, in this way, international comparison enriched the overall ndings. The dataset and case studies provided interesting indications of the views of young people from our four countries regarding the city. As a source to inform planning of school geography teaching, these images suggest two starting points. First, the mediated image of the city could be

Childrens Geographies

139

a way in to the students thinking, perhaps suggesting the value of exploring the depiction of the city in lm (see, for example, Taylor 2004). Secondly, students experiences of the city as a place of leisure and consumption could be a way in to considering the mutual constitution of the global and the local (Massey 2005). At the time of our data collection, students everyday urban environments were neglected in geography teaching, yet these offer a motivating context for many contemporary urban issues in geography courses. For example, students drawings of cities connected to current ideas about landscapes of consumption, topics currently familiar in urban geographies at university level, yet rarely considered within geography education internationally. In the UK, recent projects such as Living Geography (Geographical Association 2009) have encouraged innovative approaches to students local environments in geography education, but there is still some way to go before such approaches become the norm in our four countries. Acknowledgements

Sirpa Tani has contributed to this article as part of the research project Emotional geographies, everyday life and young people funded by the Academy of Finland (project number 130653).

Note

1. Those reproduced in this article were originally in black-and-white.

References

Alerby, E., 2000. A way of visualizing childrens and young peoples thoughts about the environment: a case study of drawings. Environmental Education Research, 6 (3), 205221. Aspeslagh, R., et al., 2000. Belgie en Nederland in Beeld. Wat weten, denken en vinden jongeren in Belgie en Nederland van elkaars landen en bevolkingen? Den Haag: Clingendael Instituut. Avraham, E., 2000. Cities and their news media images. Cities, 17 (5), 363370. Avraham, E., 2004. Media strategies for improving an unfavorable city image. Cities, 21 (6), 471479. Beneker, T., Sanders, R., Tani, S., Taylor, L., and van der Vaart, R., 2007. Teaching the geographies of urban areas: views and visions. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 16 (3), 250267. Burgers, J., 2000. Urban landscapes on public space in the post industrial city. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 15 (2), 145165. Cele, S., 2006. Communicating place: methods for understanding childrens experience of place. Stockholm: Stockholm University. Available from: http://www.diva-portal.org/diva/getDocument?urn_nbn_se_su_diva-1270-2__fulltext. pdf Christensen, P., 2003. Place, space and knowledge: children in the village and the city. In: P. Christensen and M. OBrien, eds. Children in the city. Home, Neighbourhood and Community. London: RoutledgeFalmer, 1328. Collier, J. and Collier, M., 1986. Visual anthropology. Photography as a research method. Alberquerque: University of New Mexico Press. Crang, M., 1998. Cultural geography. London: Routledge. Crowe, N. and Bradford, S., 2006. Hanging out in Runescape: identity, work and leisure in the virtual playground. Childrens Geographies, 4 (3), 331346. Geographical Association, 2009. Living geography. Available from: http://www.geography.org.uk/projects/ livinggeography/ Hall, S., 1997. Introduction. In: S. Hall, ed. Representation: cultural representations and signifying practices. London: Sage, 3. Hart, R., 1979. Childrens experience of place. New York: Irvington. Holloway, S.L. and Valentine, G., 2000. Corked hats and Coronation Street: childrens imaginative geographies. Childhood, 7 (3), 335357. Kahn, P.H. and Kellert, S.R., eds., 2002. Children and nature. Psychological, sociocultural, and evolutionary investigations. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Karsten, L., 2003. Childrens use of public space. The gendered world of the playground. Childhood, 10 (4), 457473. Karsten, L., 2005. It all used to be better? Different generations on continuity and change in urban childrens daily use of space. Childrens Geographies, 3 (3), 275290.

140

T. Beneker et al.

Knox, P. and Pinch, S., 2006. Urban social geography: an introduction. New York: Prentice Hall. Korpela, K., 2001. Koettu terveys ja asuinympariston mieluisat ja epamieluisat ymparistot. In: K. Korpela, J. Paivanen, R. Sairinen, S. Tienari, M. Wallenius and M. Wiik, eds. Melukyla vai mansikkapaikka? Asukkaiden ja asiantuntijoiden nakemyksia asuinalueiden terveellisyydesta, Suomen ymparisto 467. 123141. Kotler, P., Haider, D.H., and Rein, I., 1993. Marketing places. New York: Free Press. Lynch, K., 1960. The image of the city. Cambridge: MIT Press. Massey, D., 2005. For space. London: Sage. Matthews, H., 1992. Making sense of place: childrens understandings of large-scale environments. Hemel Hemstead, UK: Harvester Wheatsheaf. Matthews, H., et al., 2000. The unacceptable aneur. The shopping mall as a teenage hangout. Childhood, 7 (3), 279294. McKendrick, J., 2000. The geography of children: an annotated bibliography. Childhood, 7 (3), 359388. Moore, R.C., 1986. Childhoods domain: play and place in child development. London: Croom Helm. Nairn, K., Panelli, R., and McCormack, J., 2003. Destabilizing dualisms. Young peoples experiences of rural and urban environments. Childhood, 10 (1), 942. OBrien, M., Jones, D., Sloan, D., and Rustin, M., 2000. Childrens independent spatial mobility in the urban public realm. Childhood, 7 (3), 257277. Ono, R., 2003. Learning from young peoples image of the future: a case study in Taiwan and the US. Futures, 3, 737758. Rissotto, A. and Giuliani, M.V., 2006. Learning neighbourhood environments: the loss of experience in a modern world. In: C. Spencer and M. Blades, eds. Children and their environments. Learning, using and designing spaces. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 7590. Skelton, T. and Valentine, G., eds., 1998. Cool places: geographies of youth cultures. London: Routledge. Spencer, C. and Woolley, H., 2000. Children and the city: a summary of recent environmental psychology research. Child: Care, Health and Development, 26 (3), 181198. Taylor, L., 2004. Re-presenting geography. Cambridge: Chris Kington Publishing. Taylor, L., 2007. Sumo, sushi and samurai: year 9 construct Japan. In: J. Halocha and A. Powell, eds. Conceptualising geographical education. London: International Geographical Union Commission on Geographical Education/Institute of Education, 8196. Taylor, L., 2009. Children constructing Japan: material practices and relational learning. Childrens Geographies, 7 (2), 173189. Thomson, J.L. and Philo, C., 2004. Playful spaces? A social geography of childrens play in Livingston, Scotland. Childrens Geographies, 2 (1), 111130. Tuominen, M., 2007. Siis tosi turvallinen paikka. Helsingin turvallisuuskysely vuonna 2006. Helsingin kaupungin, Tutkimuskatsauksia, 2007 (6). Uzzell, D.L., 1995. The myth of the indoor city. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 15, 299310. Van Ginneken, J., 1998. Understanding global news: a critical introduction. London: Sage. Wridt, P., 2006. Columbine cougars in the community: a neighborhood guidebook by the students and teachers of Columbine Elementary School. An initiative of the Children, Youth and Environments Center for Research and Design (http://thunder1.cudenver.edu/cye/) in the College of Architecture and Planning and the University of Colorado at Denver and Health Sciences Center.

Copyright of Children's Geographies is the property of Routledge and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Frozen Path To EasthavenDocument48 pagesThe Frozen Path To EasthavenDarwin Diaz HidalgoNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Full Download Bontragers Textbook of Radiographic Positioning and Related Anatomy 9th Edition Lampignano Test BankDocument36 pagesFull Download Bontragers Textbook of Radiographic Positioning and Related Anatomy 9th Edition Lampignano Test Bankjohn5kwillis100% (22)

- Benson Ivor - The Zionist FactorDocument234 pagesBenson Ivor - The Zionist Factorblago simeonov100% (1)

- Leonard Nadler' ModelDocument3 pagesLeonard Nadler' ModelPiet Gabz67% (3)

- Auditing Theory Auditing in A Computer Information Systems (Cis) EnvironmentDocument32 pagesAuditing Theory Auditing in A Computer Information Systems (Cis) EnvironmentMajoy BantocNo ratings yet

- VDA Volume Assessment of Quality Management Methods Guideline 1st Edition November 2017 Online-DocumentDocument36 pagesVDA Volume Assessment of Quality Management Methods Guideline 1st Edition November 2017 Online-DocumentR JNo ratings yet

- TOPIC 2 - Fans, Blowers and Air CompressorDocument69 pagesTOPIC 2 - Fans, Blowers and Air CompressorCllyan ReyesNo ratings yet

- 60 Plan of DepopulationDocument32 pages60 Plan of DepopulationMorena Eresh100% (1)

- Mineral Resource Classification - It's Time To Shoot The Spotted Dog'!Document6 pagesMineral Resource Classification - It's Time To Shoot The Spotted Dog'!Hassan Dotsh100% (1)

- Porsche Dealer Application DataDocument3 pagesPorsche Dealer Application DataEdwin UcheNo ratings yet

- Electron LayoutDocument14 pagesElectron LayoutSaswat MohantyNo ratings yet

- Lifecycle of A Frog For Primary StudentsDocument10 pagesLifecycle of A Frog For Primary StudentsMónika KissNo ratings yet

- EE - 2014-2 - by WWW - LearnEngineering.inDocument41 pagesEE - 2014-2 - by WWW - LearnEngineering.inprathap kumarNo ratings yet

- PresentationDocument6 pagesPresentationVruchali ThakareNo ratings yet

- Pep 2Document54 pagesPep 2vasubandi8No ratings yet

- AlligentDocument44 pagesAlligentariNo ratings yet

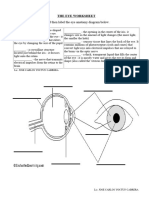

- The Eye WorksheetDocument3 pagesThe Eye WorksheetCally ChewNo ratings yet

- Bridging The Divide Between Saas and Enterprise Datacenters: An Oracle White Paper Feb 2010Document18 pagesBridging The Divide Between Saas and Enterprise Datacenters: An Oracle White Paper Feb 2010Danno NNo ratings yet

- Adolescence Problems PPT 1Document25 pagesAdolescence Problems PPT 1akhila appukuttanNo ratings yet

- Alliance For ProgressDocument19 pagesAlliance For ProgressDorian EusseNo ratings yet

- Case StarbucksDocument3 pagesCase StarbucksAbilu Bin AkbarNo ratings yet

- 525 2383 2 PBDocument5 pages525 2383 2 PBiwang saudjiNo ratings yet

- Nursing Care Plan TemplateDocument3 pagesNursing Care Plan TemplateJeffrey GagoNo ratings yet

- Solutions - HW 3, 4Document5 pagesSolutions - HW 3, 4batuhany90No ratings yet

- Aa DistriDocument3 pagesAa Distriakosiminda143No ratings yet

- Mat101 w12 Hw6 SolutionsDocument8 pagesMat101 w12 Hw6 SolutionsKonark PatelNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER THREE-Teacher's PetDocument3 pagesCHAPTER THREE-Teacher's PetTaylor ComansNo ratings yet

- Anglo Afghan WarsDocument79 pagesAnglo Afghan WarsNisar AhmadNo ratings yet

- Subtotal Gastrectomy For Gastric CancerDocument15 pagesSubtotal Gastrectomy For Gastric CancerRUBEN DARIO AGRESOTTNo ratings yet

- Design of Ka-Band Low Noise Amplifier Using CMOS TechnologyDocument6 pagesDesign of Ka-Band Low Noise Amplifier Using CMOS TechnologyEditor IJRITCCNo ratings yet