Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Arbitration

Uploaded by

Rohit NairOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Arbitration

Uploaded by

Rohit NairCopyright:

Available Formats

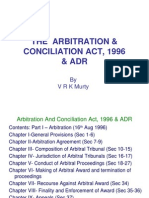

Arbitration Act 1996

1. INTRODUCTION: Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) has now been propagated and successfully implemented in the offline non-virtual world. It refers to the use of methods like arbitration, mediation,

negotiation, med-arb, etc. to solve disputes rather than the traditional litigation way. Arbitration has been especially popular in international commercial transactions where the parties are able to decide on their choice of law by which they want to be governed and jurisdiction in which they want to take up the dispute. Since the jurisdiction has been a critical issue in resolution of online disputes, many online ADR agencies have sprung up in recent times providing such facilities to parties for quick and efficient dispute resolution. The general pattern is that of the grieving party to approach the ADR agency, which in turn will contact the defendant. Then, under the aegis of the agency, both the parties solve their disputes online through emails and video conferencing without the necessity of being physically present as in litigation or off-line ADR. Further, being able to decide online, they are not confronted with jurisdictional issues at all. Such a method is being characterized as both cost efficient and time-efficient and of course, the process being very much within the control of the parties.

Arbitration Act 1996 Alternate dispute resolution is better known as Arbitration. The Arbitration and Conciliation Act 1996 is much more

comprehensive than the repealed 1940 Act. It consists of 86 Section divided into 4 Parts. Part 1 relates to Domestic as well as International Arbitration, Part 2 relates to Enforcement of Foreign Awards under the New York and Geneva Conventions, Part 3 relates to Conciliation and Part 4 contains supplementary provisions. The act has 3 schedules. The 1st schedule reproduces the provisions of the New York convention on recognition of enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards, the 2nd schedule consist Provisions of the Geneva Protocol of Arbitration Clauses of 1923 and the 3rd schedule contains Provisions of Geneva Convention on execution of Foreign Arbitral Awards. Part 2 is virtual reproduction of the provision of the repealed 1937 Act and The 1961 Act excepting the deletion of section 9(1) (b) of both the Acts. The Act seeks to make the Arbitration and Conciliation law on the line of the recommendations of United Nations and the Modern Law adopted by the United Nation Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL). It has provided a unified formula for both international commercial arbitration and

domestic arbitration and has consolidated the entire law of arbitration in one single Act.

Arbitration Act 1996 1.1 Special features of Arbitration Act, 1996

The Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 is much more comprehensive that the repealed 1940 Act. It consists of 86 sections divided into four parts. Part I relates to domestic as well as international arbitrations, Part II relates to enforcement of foreign awards under the New York and Geneva Conventions, Part III relates to conciliation and Part IV contains

Supplementary Provisions. Some of the recognized provisions are as follows:-

(1) Reduction of court intervention:

The 1940 act had given considerable powers to the court to intervene before, in-between, and after the arbitral proceedings.

Section 8, 9,10,12,20 read with section 4 of the 1940 act dealt with the circumstances in which court could interfere before the arbitral proceedings.

Section 5 of the new act is its most important feature. It provides that judicial authority can intervene only where it is so specially provided in Part I... The courts powers to intervene are contained in Section 9 for making interim measures, Section 11 for appointment of arbitrator, Section 14 for taking decision on 3

Arbitration Act 1996 termination of man date of the arbitrator, Section 17 for rendering assistance in taking evidence in arbitration

proceedings, Section 34 for setting aside the award, Section 37 in deciding Appeals and Section 39 in issuing directions to the arbitral tribunal to deliver the award in the circumstances envisaged therein.

(2) Party Autonomy:

The new act recognizes maxim um possible party autonomy in matters relating to arbitration. Autonomy starts from the

formation of arbitral tribunal and appointment of arbitrators. Parties are free to determine the number of arbitrators, with only one restriction that the number should not be even number as per section 10.section 11(2) permits the parties to agree on the procedure for appointing the arbitrator. There is party autonomy also in fixing the place of arbitration (section 20) and the language to be used in the proceedings (section22).

(3) Reduction of grounds of challenge:

Section 34 deals with grounds of challenge to award .As compared with the grounds under section 1940 act they are not considerably reduced but also are qualitatively different. Error apparent on the face of the award was the most misused ground 4

Arbitration Act 1996 for settling aside award under the 1940 Act. Section 34(4) contains a salutary provision empowering the court to adjourn its proceedings in order to give an opportunity to the arbitrators themselves to take such action as may be necessary to eliminate the ground of challenge against the award.

(4) Interim award:

Section 2(1) (c) defines arbitral award as including an interim award. The Arbitral Tribunals have been endowed with the power to pass interim award which is enforceable like a final award. Sub-section (6) of Section 31 empowers the arbitral tribunal with the power to make an interim award on any matter with respect to which it could make a final award.

(5) Interim measures:

Section 9 of the new act relates to interim measures taken by the court and Section 17 relates to interim measures taken by the Tribunal. The 1940 act gave no power to the Tribunal to pass interim orders of injunction etc. and the parties had to resort to the courts under section 41(b) of the 1940 act for that purpose. The new act not only preserves that power of the court but provides for the exercise of power even before the start of the arbitral proceedings. 5

Arbitration Act 1996 (6) No time limit for making the award:

Under 1940 Act specific time limit was fixed for the Arbitrators and Umpires to make award, four months for the Arbitrator and two months for the Umpire.(Para three &four of First Schedule: Section 3 ).The limit were generally never adhered to and there have been extensions after extensions. The time has limit has now been abolished.

(9) Umpire system Abolished:

The 1940 Act provided that where even number of Arbitrators was appointed and such Arbitrators failed to make an award, within the specified time, the Umpire should enter on the reference in lieu of Arbitrators. Umpire system is now abolished. The number of arbitrators has now been left to the parties, but with one limitation and that pertains to appointment of not only even number of Arbitrators. The Arbitrators so appointed shall now appoint a third Arbitrator called the Presiding Arbitrator.

(10) Code of Civil Procedure and Evidence Act:

Section 19 of the new act in terms states that the tribunal shall not be bound either by the Code of Civil Procedure or evidence Act. However, the parties are free to agree in the procedure to be 6

Arbitration Act 1996 followed by the arbitral tribunal in the conduct of proceedings. The freedom given to the parties to agree on the procedure under the rules of arbitration of established arbitral institutions. It may b e mentioned that Limitation Act 1963 however, is made applicable.

1.2(a) Definition of arbitrator according to Whartons Law Lexicon

the civilians says Wharton , make a difference between arbiter and arbitrator , though both found their power in the compromise of the parties; the former being obliged to judge according to the customs of law; whereas the latter is at liberty to use his own decision , and accommodate the difference in that manner which appears most just and equitable

Arbitration Act 1996

(b) Definition of Arbitrator according to Indian Law.

An arbitrator is the person to whose attention the matters in dispute are submitted by the parties; a judge of the parties own choosing, whose functions are judicial and whose duties are not those of mere partisan agent, but of an impartial judge, to dispense equal justice to all parties, and to decide the law and facts involved in the matters submitted with a view to

determining and finally ending the controversy

Where the parties agree to refer their dispute to a third person for decision and where that person has to some judicial or quasijudicial work, his decision is an award. If a dispute and in deciding tat dispute he holds a judicial inquiry and comes to a judicial decision, then the person is called an arbitrator. The distinguishing feature is that if the matter is referred to a person and he is not called upon either to hold a judicial inquiry or to give a judicial decision but it is permissible to him to rely on his own skill or experience in order to arrive at a particular decision, then that person is not an arbitrator .an arbitrator is an quasijudicial position. Therefore, the first essential requisite in persons occupying that post is judicial impartially and freedom from bias

Arbitration Act 1996 1.3 Ground Realities of Arbitration

Arbitration Agreement is a bargain between the parties to abide by the decision of the appointed arbitrator, which can be challenged only on the restricted grounds listed in section 30 of the arbitration cat i.e. misconduct etc. The parties rely on his expertise in the special field of controversy in question which is expected to enable him to comprehend the rival contentions better and resolve them expeditiously and satisfactorily

untrammeled by the procedural laws, Civil Procedure Code and Evidence Act but there is limit to his liberties. He is required to be honest, independent and impartial and decide according to the law the land otherwise court can intervene to set him right.

Despite the supervisory powers of the court, abuse of the process of arbitration is rampant says Kerala High Court in AIR 1990 Kelara 101 at 107, State of Kerala v. Joseph. Supreme Court has observed in AIR 1981 SC 2075, Ms Gurunank Foundation v. Ms Rattan Sigh and Sons: interminable, time consuming, complex and expensive court procedures impelled jurists to search for an alternative forum, less formal, more effective and speedy for resolution of disputes avoiding procedural claptrap and this led them to the Arbitration ActHowever , the way in which the proceedings under the act are conducted and without an exception challenged in courts , has made lawyers laugh and 9

Arbitration Act 1996 legal philosophers weep. Experience shows and law reports bear ample testimony that the proceedings under the act have become highly technical accompanied by an unending prolixity, at every stage providing a legal trap to the unwary. Informal forum chosen by the parties for expeditious disposal disputes has by the decision of the courts being clothed with legalese of an unenforceable complexity. Further the Supreme Court goes so far as to say that the system of dispute resolution has , of late , acquire a certain degree of notoriety by the manner in which in many cases the financial interest of the government has come to suffer by award which has raised eyebrows by doubts as to their rectitude and propriety . It will not be justifiable for governments or their instrumentalities to enter into arbitration agreement which do not expressly stipulate the rendering of recent and asking awards. Government and their

instrumentalities should , as a matter of policy and public interest if not as a compulsion of law-ensure that wherever

they enter into agreements for resolution of disputes by resort to private arbitrations , the requirement of speaking awards is expressly stipulated and ensured. It is for governments and their instrumentalities to ensure in future this requirement as a matter of policy in large public interest. Any lapse in that behalf might tend itself to and perhaps justify, the legitimate criticism that government failed to provide against possible prejudice to public interest 10

Arbitration Act 1996

The Types of Arbitrations The Indian Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 applies to both domestic arbitration in India and to international arbitration. Section 2(1)(f) of the Act defines "International Commercial Arbitration" as arbitration relating to disputes arising out of legal relationships, whether contractual or not, considered as

commercial under the law in force in India where at least one of the parties is: 1. an individual who is a national of, or habitually resident in any country other than India; or

2. a body corporate which is incorporated in any country other than India; or

3. a company or an association or a body of individuals whose central management and control is exercised in any country other than India; or

4. The Government of a foreign country.

11

Arbitration Act 1996

1.4 DEVIATION FROM THE UNCITRAL MODEL LAW UNCITRAL Model Law was the basic ideal before the law makers while making the new Act. But the provisions are not Just copies of the provisions of the Model Law. On certain aspects the provisions of the new Act differ and some of the major differences can be stated thus :(a) The Model Law does not contain any limitation on the number of Arbitrators. Where the parties fail to determine the number of Arbitrators. The Model Law provides that the number shall be three. Section 10(1) of the new Act deals with the number of Arbitrators and mandates that the number shall not be even. Section 10(2) provides that in the absence of agreement about the number, the number of Arbitrators will be one.

(b) Model Law permits the parties to approach a Court or Authority for appointment of a third Arbitrator or Sole Arbitrator as the case may be. in cases where the parties fail to reach an agreement. Under the new Act this power in the case of domestic arbitrationis vested with the Chief Justice of the concerned High Court or any person or Institution designated by him and in case of International Commercial Arbitration such power is given to the Chief Justice of India or any person or Institution designated by him.

12

Arbitration Act 1996

(c)

The Model Law empowers the tribunal to decide on the

challenge to an Arbitrator and if the challenge fails the party can approach the Court at that stage against the order. Section 13 of the new Acts does not permit the party to approach the Court at that stage. The stage to challenge that order of arbitrator is after the award, under Section 34. Same is the position regarding challenge to the jurisdiction of arbitrator. (d) The new provisions which are alien to the Model Law are: (i) Award of interest by the Tribunal in a detailed manner, under Section 31(7), (ii) Cost of arbitration, under Section 31, (iii) Enforceability of an award in the same manner as if it were a decree of a Court under Section 36 in situations where award is not challenged within the prescribed period or the challenge has been unsuccessful, (iv) Appeals in respect of certain matters. Under Section 37, (v) Fixing the amount of deposit or supplementary deposit as an advance for the cost of arbitration, under Section 38, (vi) Lien of arbitral award and disputes as to costs of arbitral Award, under Section 39,

13

Arbitration Act 1996

(vii) Non- discharge of arbitration agreement by death of a party, Under Section 40, (viii) Rights of a party for arbitration agreement in relation to insolvency proceedings against the party thereto, under Section 41, (ix) Identification of Court having exclusive jurisdiction over the arbitral proceedings, under Section 42, (x) Applicability of the Limitation Act, 1963 to arbitrations as it applies to proceedings in court and fixing the date of

commencement of arbitration and other matters.

14

Arbitration Act 1996 1.5 Time Limit Arbitration being an expeditious process enjoins on the arbitrator to conclude the proceeding with all possible dispatch .if the court appoints an arbitrator, the court can fix the time within which the proceedings have to be completed. If the arbitrator has been appointed or is to be appointed outside the court, parties may set the time for completion of arbitration

proceedings in the agreement itself or subsequently by a separate agreement. In absence of such a consensual

prescription of period, statutory provision contained in rule 3 of First Schedule of Indian Arbitration act, 1940m prescribing 4 months as the period will come into play.

Consideration of rule 3 of first schedule of arbitration act

Rule 3 of the first schedule of the Indian arbitration act 1940 reads as

The arbitrators shall make their award within four months after entering on the reference or after having been called upon to act by notice in writing from any party to arbitration agreement or within such extended time as the court may allow

15

Arbitration Act 1996 However, it must be noted that the period of four months prescribed by Rule 3 of the first schedule comes into play only when there is no provision in the arbitration

agreement as regards the time-limit within which the award is to be made. If there is any provision regarding the time-limit that provision will be given effect to.

This rule corresponds to rule 3 of the first schedule to clause (c) of the first schedule of the arbitration act of 1899 which in its turn corresponded to clause (c) of first schedule of the English arbitration act of 1899. both English act of1899 and the Indian act of 1899 prescribed the period of three months .perhaps this was found to be short and the Indian act of 1940 enlarged it to four months . While in England the idea of having defined period. Was given up in arbitration act 1934 , it is not clear why the Indian arbitration act of 1940 , which follows in essential particulars the English act of 1934 , still adhered to the old idea old defined period.

Rule 3 of the first schedule of the Indian act contemplates two alternatives: (a) after entering on reference and (b) after having been called upon to act by notice in writing from any party to the arbitration agreement.

16

Arbitration Act 1996 The limitation of four months would start running from the point in time covered by either of the alternatives. If the arbitrator has entered on the reference, four months would start running from the date he has actually entered on the reference .But, if he has not entered on the reference a party to the arbitration agreement may call upon him by notice in writing to do so. Four months would start running from the date of service of that notice on him. But the question arises: if the arbitrator actually enters on the reference after service of such notice, from the date is the period of four months to be computed? The limitation would start running from the date of service of that notice, but as soon as he enters on the reference the limitation will be computed from the date when he enters on the reference. In Baring Gould v. Sharpengton Combined Pick and Shorat Syndicate the view taken by the Master of the Rolls, Lord Lindley, was the provisions entering on the reference, and having been called upon to act by notice in writing, are alternatives in this sense that where no reference Is entered upon at all, then the time runs from the notice calling upon the arbitrators to act. But, on the other hand, even although the arbitrators m ay be called reference they have three months from that moment for making their awardTo hold otherwise would seem to strike out from clause (3) the words within three months 17

Arbitration Act 1996 after entering on the reference, in a case where one of the parties happened to call upon the arbitrators to act before they began the reference. This ruling has been followed by the Allahabad High Court in Sardarmal Hardat Rai v. Sheo Baksh Rai Sri Narain.

Normally the principle of limitation is that once the limitation starts running from specified co terminus. It cannot be shifted to another co terminus. But, this principle would not apply to the present case b e cause of the specific language used in Rule 3 of the first schedule, as to hold otherwise would seem to strike out from that clause the words within four months after entering on reference.

The period of four months has to be computed according to the principles of the Limitation Act, that is, the first date is to be excluded an d the last date has to be included.

Rule 3 of the First Schedule contemplates that the period of four months may be extended by court, for which provision is made in Section 28 of the Act.

18

Arbitration Act 1996 1.6 Development of arbitration in India

In ancient India, long before the courts of law were established, the decisions of the village panchayat were accepted as binding on the parties. The pantheist was composed of the chief of then community and some selected or elected residents of the village. The pantheist can be catalogued, in their ascending order of the importance, as (1) Kula (2) Sreni and Puga. The decision of the Kula or kinsmen was subject to revision by the Sreni , which in turn could be revised by Puga. From the decision of the Puga, an appeal lay finally to the sovereign.

With the advent of British rule in India, the panchayati system of arbitration was not abrogated, but the; provision was made in Bengal regulation of 1772 that in all cases of disputes accounts, etc.,it shall be recommended to the parties to submit the decisions of their cause to arbitration , the award of which shall become decree of the court.. Further facilities for arbitration were given by regulations of 1780 and 1781. The regulations of 1781 provided that no award of any arbitrator be set aside except upon full proof made by oath of two credible witness that the arbitrators have been guilty of the gross corruption or partiality in the cause in the course they have made their award

19

Arbitration Act 1996

1.7 Varieties of Arbitrations Arbitration has its own ethos. It is developing its own procedure. Its popularity is growing. It is being institutionalized. It is being systematized .it is carving for itself a sphere of activities where a speedy inexpensive informal decision, amicably arrive at is required to be handed down to the parties, in order to sustain smooth business relations. It is hoped that the institution of arbitration will go from strength to strength.

Varieties of Arbitrations:

(1) Ad-hoc arbitration-at first arbitration resorted to as and when a dispute arose between the parties to a business transaction, which could not be settled by negotiations in the shape of conciliation or mediation. As the occasion required arbitration , it was termed as ad-hoc

(2) Construction inbuilt arbitration-as business transactions increased in number and complexities with concomitants increased in clashes between the parties, occasions

requiring arbitration became frequent and the increase number called for regular machinery in the shape of inbuilt arbitration clause, an integral part of the contract covering

20

Arbitration Act 1996 present or future dispute- existing or potential-and the machinery devised was reference to a named arbitrator or an arbitrator to; be appointed by a designated authority.

(3) Institutional arbitration-another an perhaps more suitable for some was institutional arbitration , where the parties agree in advance in the event of future dispute , they will be settled by arbitration by the named institute of which one or more of then\m where members. The institute where governed by pre-published rules known to the parties stipulating appointment of arbitrators form among the panelists of specialists listed by the institute.

(4) Statutory arbitration-statutory arbitration was imposed on the parties by the statute governing them. While (1), (2) & (3) are based on consent of the parties; statutory

arbitration is despite their consent. While first three are voluntary the fourth is compulsory, the statute making lit binding on the parties as the law of the land, the parties cannot opt out of it but have to abide by it.

21

Arbitration Act 1996

1.8 The Foremost Challenge in the Arbitration Process Among various problems arising, at the threshold, it is imperative that there should exist an arbitration agreement. It is necessary that either there should be an arbitration agreement or at least an arbitration clause in any commercial agreement made

between the contracting parties. Question, many and varied, arise. One of the most important questions which strike at the very root of this process is the selection of the arbitral panel itself? Parties face right at the outset the question of choice of arbitrator(s). When it should be decided? Who should decide? Who should be the arbitrator(s)? How many arbitrators? What should be the qualification of the arbitrator(s)? Where would one find the arbitrator(s)? Are they neutral? Are they impartial? Are they independent? their What area should of be their the rights limit of and their

responsibilities,

working,

functioning? These queries linger at the background as we try to develop our arbitration clauses.

Ad Hoc Arbitration and Institutional Arbitration: For the purpose of constituting an arbitral panel, one can pursue one of the two paths available. One can go for ad hoc arbitration whereby the parties themselves constitute an arbitral panel and

22

Arbitration Act 1996

make their own rules for arbitration. On the other hand, there is the option of institutional arbitration. Opting for institutional arbitration gives the benefit of not only making use of the welltested arbitration rules and procedures of the institution but also being assured of the presence of well-experienced and qualified arbitrators from the panel maintained by the institution. Further, in an institution, the professional staff is available to guide disputants through the arbitration process. Among the prominent foreign arbitral institutions, mention can be made of American Arbitration Association (AAA) in USA, London Court of International Arbitration (LCIA) in United Kingdom, Stockholm Chamber of Commerce (SCC) in Sweden and Arbitral Center of the Federal Economic Chamber in Vienna. In India, we find institutions like the for Indian Council are of Arbitration, similar

International

Centre

ADR,

which

offering

arbitration and mediation facilities. However, all, but few, remained off-line arbitration and conciliation centers. With the advent of the Internet as a globally recognized vehicle for information travel and exchange, the ADR was re-born both in terms of cost-efficiency and speed. We witnessed the birth of various online ADR websites. These websites function the same way as the arbitral institutions and provide similar services. The only difference being is that they do not have any restrictions as

23

Arbitration Act 1996

to physical space and are available at any moment of time at any given place where one might have Internet facilities available.

1.9 Duties of the arbitrator

As per the English law, the first duty of the arbitrator on the receipt of his appointment is to see that his appointment is in order, and in case it is not, he should have it put in order before he proceeds with the arbitration. He should also find out whether the submission (together with the agreement , if any , under which it is made ) requires him to possess any special qualification ; and if it dose , he should make sure either that he complies with the requirement or that his failure to comply is

known to both then parties and acquiesced in by them. The arbitrator should also satisfy himself that the submission is wide enough to cover the disputes with which he is to deal. In this connection he should go beyond a mere formal examination to make sure that he has the authority to decide the dispute put before him.In addition, he should, as soon as he knows what the real nature of the dispute is, consider whether he is authorized to deal effectively with it, or whether some thing further is neededsome special power to give directions, for instance , or authority to deal with some related dispute, that ought to be dealt with at

24

Arbitration Act 1996 the same time, if it is not to lead to multiplicity of proceedings between the parties. Such matters are best settled at the earliest possible moment, for if they are left until a later stage of arbitration it will often be found that one side or the other refuses to agree to amendment of the submission in the hope of thereby securing some tactical advantage: Whereas at the in inception of the arbitration it is less likely that the giving of additional powers to the arbitrator will seem to favour one side or the other,. In case where the arbitrator has at that stage sufficient under standing of the dispute, points of this sort can with advantage b e dealt with at the preliminary meeting.

25

Arbitration Act 1996

1.10 Arbitral Disputes

The first point that usually arises in interpreting that scope and content of the arbitration agreement is as to what matters are covered by that agreement which have to be referred to the arbitrator contemplated by it . The allied question which comes up for consideration is bas to what matters are accepted from the scope of the arbitration agreement?

The test, whether a particular matter is covered or not, is laid down by the supreme court in AIR1969 SC 488.. Is reliance placed on a term of contract for seeking relief? If so, it is covered by the arbitration clause. If not, it is so covered.

A question arose whether there has been full and final settlement of the claims under the contract is a dispute covered by the arbitration agreements. supreme court has held in AIR 1974 SC 158, Damodar Valley Corporation v K. K Kar that the question whether there has been full and final settlement of a claim under the contract was itself a dispute arising upon or in relation to or in connection with the contract and , therefore , reference to the arbitrator was not beard . it was further held in that ruling that the question whether the termination was valid or not and

26

Arbitration Act 1996 whether damages where recoverable for some wonderful for such wrong full termination, did not effect the arbitration clause or the right of the party to invoke it for appointment of an arbitrator reliance was placed on 1942 AC356 = (1942)1 AVER 337 and AIR 1959 SC 1362 for the purpose.

27

Arbitration Act 1996 2. Arbitration Agreement Section 7 Arbitration Agreement means an agreement by the parties to submit to arbitration all or certain disputes which have arisen or which may arise between them in respect of a defined legal relationship, whether contractual or not. An arbitration agreement may be in the form of an arbitration clause in a contract or in the form of a separate agreement. An arbitration agreement shall be in writing. An arbitration agreement is in writing if it is contained in 1. A document signed by the parties; 2. An exchange of letters, telex, telegrams, or other means of telecommunication agreement; or 3. An exchange of statements of claim and defense in which the existence of the agreement is alleged by one party and not denied by the other. The reference in a contract to a document containing an arbitration clause constitutes an arbitration agreement if the contract is in willing and the reference is such as to make that arbitration clause part of the contract. which provide a record of the

Sec.7 Definition and form of arbitration agreement Arbitration agreement is an agreement by the parties to submit to arbitration, whether or not administered by a permanent 28

Arbitration Act 1996 arbitral institution, all or certain disputes which have legal arisen or which may arise between them in respect of a defined legal relationship, whether contractual or not. An arbitration

agreement may be in the form of an arbitration clause in a contract or in the form of a separate agreement. The arbitration agreement shall be in writing. An agreement is in writing if it is contained in a document signed by the parties or in an exchange of letters, telex, telegrams or other means of telecommunication which provide a record of the agreement. The reference in a contact to be document containing an arbitration clause constitutes an arbitration agreement provided that the entire entire contract is in writing and the reference is such as to make that clause part of the contract.

Scope of Arbitration: 1. In principle the arbitrator has no jurisdiction to enlarge the scope of reference and to do so is misconduct. 2. Disputes specifically excluded from the purview of the arbitration clause are not referable to arbitration. 3. Arbitration must be confined to disputes which were subject-matter of arbitration before the first arbitrator. Appointment of new Arbitrator does not enlarge the scope of the reference. 4. Where order of reference entitled the arbitrator to consider such other points raised in the pleadings before the court at 29

Arbitration Act 1996 5. Suit stage claim rose by the party not in the suit stage, but in another suit, was held to be beyond reference and hence not maintainable by the Supreme Court. 6. On considerations of equity the Supreme Court directed the arbitrator even to consider counter-claim together with the claim even though technically it can be stated that the counter-claim was not referred. 7. An award passed by arbitrator in a reference for deciding 30 claims was set aside by the court on the ground of want of jurisdiction in that arbitrator. Appointment of new arbitrator was ordered and the dispute between the parties was referred to second Arbitrator. Seven more claims pertaining to the same dispute were added. Objection was raised that the new seven claims were not maintainable before the arbitrator. Supreme Court upheld the award even relating to additional seven claims on the basis that they also pertained to the same disputes and there was

intention to refer all disputes to arbitration.

Essentials of an Arbitration Agreement: Essentials of an Arbitration Agreement providing for arbitration are that there must be an agreement between the parties and the parties must be ad idem, such an agreement should be in writing and that there is intention of the parties to have their disputes or differences referred and decided through arbitration . 30

Arbitration Act 1996 The essentials of an arbitration agreement as judicially aatated in AIR 1992 Orissa 35 & 3 in number1. Parties 2. Disputes and 3. Finality of the decision. This is what the ruling states: The clause of arbitration in the instant case was worded as under: In case of any dispute or differences of opinion arising out of the agreement, the matter shall be referred for orders of the Commissioner, Agriculture and Rural Development, Government of Orissa, Bhubaneswar whose decision on the issue shall be final and binding on both the parties. The statutory essentials may be listed as: 1. An agreement 2. In writing 3. Relating to either present or future differences, 4. Whether an arbitrator is named therein or not. Bharat Engineering Corporation case In this case, the clause under the agreement read as follows:

In the event of any dispute or differences between the parties.. the Contractor; after 90 days of his presenting his final claim on disputed matters, may demand in writing that the dispute or differences be referred to arbitration, such demand for

31

Arbitration Act 1996

arbitration shall specify the matters which are in question, dispute or difference, and only such dispute or difference of which the demand has been made and no other, shall be referred to arbitration.

It was held that this arbitration clause did not amount to an arbitration agreement. An agreement to agree or a contingent agreement was not permissible under section 2 (a) of arbitration act. As the arbitration agreement is required to be mutual, only one party having right to exercise the option to commence the arbitration proceedings would not qualify as an arbitration agreement. It is only when the option was exercised that it resulted in an arbitration agreement with mutual rights to make the reference.

Government arbitration agreement: Arbitration agreement in writing and signed, if it relates to government requirement contract of will have of to the satisfy the mandatory Normally

Article

299

constitutions.

arbitration agreement forms a part of the government contract, it is as if 2 contacts are rolled into one. Such an agreement 1. Must be expressed to be made by the president or the governor 2. It must of course be executed in writing

32

Arbitration Act 1996

3. The execution must be such person and in such manner as the government might direct or authorize. If the agreements have not been executed in accordance with requirements of Article 299, it cannot be enforced by or against the government (AIR 1967 SC 203)

If agreements involving valuation of Rs.50000 and above are to be signed by the Superintending Engineer, any agreement signed by the executive engineer would be non-est. in law, even though the negotiations may have been entered into by the

Superintending Engineer himself.

33

Arbitration Act 1996

2.1 How to Draft an Arbitration Agreement? A good arbitration agreement is one which minimizes

complications when disputes arise. However, many a times people neglect to pay attention while drafting an arbitration agreement. Before finalizing an arbitration agreement, the terms should be thoroughly discussed and negotiated to avoid any

misunderstanding at a later stage. Arbitration lawyers from all applicable jurisdictions must be consulted before finalizing any arbitration agreement... Before signing an Arbitration Agreement the following must be properly addressed:

Applicable law to arbitration Location of Arbitration Number of Arbitrators Language of Arbitration Discovery procedure Limitation to arbitration powers Interim measures/Provisional Remedies Privacy Rules Applicable Appeal & Enforcement 34

Arbitration Act 1996

Be aware of local peculiarities Survival after Termination of the main agreement.

The arbitration agreement should be modified as applicable under different circumstances. One brush should not paint all the painting. Model Arbitration Agreement "All and any disputes arising out of or in connection with the present agreement shall be finally settled under the UNCITRAL Model Rules of Arbitration (or another arbitration rules of your choice) by sole (or three) arbitrator (s) appointed by _________ (an arbitration institute of your choice) in accordance with the said Rules. The place of arbitration shall be _____. The arbitration shall be conducted in ______ language. The arbitration award shall be final and binding. The arbitration shall be governed under the laws of ______. "

35

Arbitration Act 1996

3. Composition of Arbitral Tribunal 3.1 Number of Arbitrators Section 10. (1) The parties are free to determine the number of arbitrators, provided that such number shall not be an even number. (2) Failing the determination referred to in sub-section (1) , the arbitral tribunal shall consists of a sole arbitrator. Article 10 as per UNCITRAL MODEL LAW- Number of arbitrators. (1) The parties are free to determine the number of

arbitrators. (2) Failing such determination the number of arbitrators shall be three. IN BRIEF:Under this section full liberties are given to the parties to determine the number of arbitrators. The only condition is that the number shall not be even. Failing such determination of number by the parties, the arbitral tribunal shall consist of a sole arbitrator as against number three prescribed under the Model Law. No optimum limit of number is prescribed under this provision as is done in the case of Conciliators where optimum limit is prescribed as three (Section 63).

36

Arbitration Act 1996 3.3 Grounds for Challenge Section 12

(1) When a person is approached in connection with his possible appointment as an arbitrator, he shall disclose in writing any circumstances likely to give arise to justifiable doubts as to his independence or impartiality. (2) An arbitrator, from the time of his appointment and throughout the arbitral proceedings, shall, without delay, disclose to the parties in writing any circumstances referred to in sub-section (1) unless they have already been informed of them by him. (3) An arbitrator may be challenged only if :-

(a) circumstances exist that give to justifiable doubts as to his independence or impartiality; or (b) he does not possess the qualifications agreed to by the parties.

(4) A party may challenge an arbitrator appointed by him, or in whose appointment he has participated, only for reasons of which he becomes aware after the

appointment has been made.

37

Arbitration Act 1996 Article 12 - UNCITRAL Model Law

(1) When a person is approached in connection with his possible appointment as an arbitrator, he shall disclose any circumstances likely to give rise to justifiable doubts as to his independence or impartiality, An arbitrator, from the time of his appointment and throughout the arbitral proceedings, shall, without delay, disclose any circumstances to the parties unless they have already been informed of them by him.

(2) An arbitrator may be challenged only if circumstances exist that give rise to justifiable doubts as to his

independence or impartiality; or if he does not possess the qualifications agreed to by the parties. A party may challenge an arbitrator appointed by him, or in whose appointment he

has participated, only for reasons of which he becomes aware after the appointment has been made.

In BREIF:Sub-section(1) provides that a prospective arbitrator is obliged to disclose to the parties in writing any circumstances likely to give rise to justifiable doubts as to his independent or impartiality . His duty of disclosure arises when a person has just approached him in connection with his possible appointment as an arbitrator and the duty is to be discharged prior to his appointment. 38

Arbitration Act 1996 But a person may be appointed without first approaching him. Sub-section (2) speaks about his duty of disclosure of

circumstances from time he is appointed till termination of arbitration proceedings. In other words, duty continues

throughout. An arbitrator is to discharge his duty without delay. Duty also relates to matters that may have risen after the appointment (1).

Removal of an arbitrator on the ground of delay in conducting the arbitral proceedings cannot be sought in the face of indolent conduct of the party seeking arbitration (2).

Sub-section (3) enumerates grounds for challenging an arbitrator. The grounds are restricted only to two factors which are (i) existence of a circumstance that give rise to justifiable doubts as to his independence or impartiality , or (ii) not possessing the qualification agreed to by the parties . The use of the word only is significant to indicate exclusion of any other grounds.

Section 16 of the arbitration act confers powers on the court to remit the award. It postulates as under:-

39

Arbitration Act 1996 4.1 Section 16. Remitting the Award

(1) The court may from time to time remit the award or any matter referred to arbitration to the arbitrators for

reconsideration upon such terms as it thinks fit.

(a) Where the award has left undetermined any of the matter referred to arbitration ,or where it determines any matter not referred to arbitration and such matter cannot be separated without affecting the determination of the

matters referred; or (b) Where the award is so indefinite as execution; or (c) Where an objection to the legality of the award is apparent upon the face of it. to be incapable of

(2) Where an award is remitted under sub-section (1) the court shall fix the time within which the arbitrator shall submit his decision to the court:

Provided

that

any

time

so

fixed

may

be

extended

by

subsequent order of the court when to modify the award.

40

Arbitration Act 1996 (3) An award remitted under sub-section (1) shall become void on the failure of the arbitrator to reconsider it and submit his decision within the fixed time.

The procedures of the section 16 of 1940 Act are: (1) Section 13 of the Arbitration Act, 1899. (2) Para 14 of the Second Schedule of the Civil Procedure Code. Arbitration act 1940 empowers the court to modify an award under section 15 of the act which postulates as under:-

Section 15: the court may by order modify or correct an award

(a) Where it appears that a part of the award is upon a matter not referred to arbitration and such part can be separated from the other part and does not affect the decision on the matter referred; or (b) Where the award is imperfect in form , or contains any obvious error which can be amended without affecting such decision; or (c) Where the award contains a clerical mistake or an error arising from an accidental slip or omission.

The power conferred under this section is discretionary 41

Arbitration Act 1996 The grounds listed in clauses (a), (b) and (c) in this section are exhaustive and therefore, inherent powers of the court cannot be exercised to correct or modify the award in any other

circumstances.

Where the award determines a matter not referred to arbitration and such matter can be separated from the other part of the award without affecting the rest of the award, the court has two courses left open, (a) to modify or correct the award itself under this clause or (b) to remit the award to the arbitrator or umpire for reconsideration under section 16(1) (a).

When the award is modified under this clause by court the decree that should be passed under section 17 must be on the modified award.

According to the Calcutta high court, the court cannot correct an award pronounced against the President of India, which should be against the Union of India. But the same of The High Court has later changed its opinion in, Union of India v Himat Singka Timber.

Severable award- If a part of the award is set aside (as contrary to law) and the part set aside is severable from the rest, the award need not be remitted. 42

Arbitration Act 1996 If the award contains a determination of all the points referred, the valid portion can be maintained and the remainder set aside.

In contrast, if the good part of the award is not severable from the bad part, the whole has to be set aside.

4.2 Interim measures ordered by Arbitral Tribunal Section 17-Interim measures ordered by arbitral tribunal

(1) Unless otherwise agreed by the parties, the arbitral tribunal may, at the request of a party, order a party to take any interim measures of protection as the arbitral tribunal may consider necessary in respect of the subject-matter of the dispute. (2) The arbitral tribunal may require a party to provide appropriate security in connection with a measure ordered under sub-section (1).

43

Arbitration Act 1996 Article 17 of UNICTRAL Model Law

Power of arbitral tribunal to order interim measures: Unless otherwise agreed by the parties, the arbitral tribunal may, at the request of a party, order any party to take such interim measures of protection as the arbitral tribunal may consider necessary in respect of the subject-matter of the dispute.

The arbitral tribunal may require any party to provide appropriate security in connection with such measures.

Scope The arbitral tribunal has inherent power to order a party to take interim measures of protection unless such power is excluded by an agreement between the parties. This power is only

legislatively recognized in this provision. As the per the subsection (2) power includes ordering security in connection with interim measures.

The list o interim measures covered under section 17 cannot by its very nature be exhaustive. In can include several things like presentations, custody, sale, protection of goods , protection of trade secrets, maintenance of machineries , works, continuation 44

Arbitration Act 1996 of certain works etc .They all must , however, be in the respect of subject-matter of dispute.

Section 37 (2) provides for an appeal against an order granting or refusing interim measures. Section 17, however, n either

empower the arbitral tribunal to enforce its neither order nor does it provide for judicial enforcement of such order. However, under section 37 (2) if a court upholds the order in appeal,

judicial enforcement of such order will be ensured. There is no bar against a party seeking enforcement of such orders through the court under section 19.

Undoubtedly , interim measures grantable by the arbitral tribunal under section 17 are different than those which are grantable by the court under section 9.but overlapping of such powers in certain cases cannot be wholly ruled out. Any practical or legal problem is not likely to arise if both the tribunal and the Court are located in India.

In the unlikely event of contradictory order, orders of the court would prevail, the court being the appellate forum.

45

Arbitration Act 1996

5 CONDUCT OF ARBITRAL PROCEEDINGS.

5.1 Section 18- Equal treatment of parties.

The party shall be treated with equality and each party shall be given a full opportunity to present his case.

As per UNCITRAL LAW- Article 18- Equal treatment of parties.

The party shall be treated with equality and each party shall be given a full opportunity of presenting his case.

In BRIEF:-

This section retaliates the well-established principles of natural justice which are expected of any judicial, quasi judicial or even administrative decisions affecting the rights of the parties. Principles of natural justice are not capable of precise definition but concept is well known and has been crystallized by judicial pronouncements made from time to time and is being

increasingly widened with the fast development of the society.

46

Arbitration Act 1996

The arbitrators are expected to perform their functions honestly and impartially and are expected to provide equal opportunity to the parties to present their case by adhering to the principles of natural justice. Ones they are appointed, who appointed should not be relevant for them. An arbitrator is not supposed to identify the interest of a party merely because of the reason that that party has appointed him.

An arbitrator must not be guilty of any act which can be construed as indicated of partiality or unfairness.

Arbitrator should not examine one party or the witness in the absence of the others. Hearing of one party in the absence of the other amounts to misconduct.

Parties should be given proper notice of hearing and each party must be given a chance of putting up his case. Unfairness and unreasonableness make the decision and the award

questionable. It is established principle of natural justice that no person should be condemned unheard. The doctrine of natural justice pervades all through the procedural law of arbitration. Its observance is the pragmatic requirement of fair play in action.

47

Arbitration Act 1996

The arbitral tribunal should not act on the personal knowledge and must derive its conclusion and findings on the material submitted before it. The matter would be different where the parties employ and arbitrator as an expert and authorize him to make use of his knowledge and expertise. In such cases he is expected to use his personal knowledge. Indeed the existence of that knowledge is the basis of his appointment. Use of personal knowledge where the agreement does not empower the

arbitrators specifically or by necessary implication, in the decision of the dispute would violate the award. Where the arbitrators received fresh evidence after the conclusion of the hearing and also acted upon it without giving the other party an opportunity to be heard a fresh, the award is vitiated. Notice to parties about closure of arbitral proceeding is a part of fair play action in view of judicial pronouncements and hence such a notice should be given so as to enable the parties to lead any additional evidence if they so desire.

48

Arbitration Act 1996

5.2 Section 19- Determination of rules of procedure

The arbitral tribunal shall not be bound by the code of civil procedure, 1908(5 of 1908) or the Indian evidence act 1872(1 of 1872). Subject to this part the parties are free to agree on the procedure to be followed by the arbitral tribunal in conducting its proceedings. Failing any agreement referred to in sub-section (2), the arbitral tribunal may subject to this Part, conduct the proceeding in the manner it considers appropriate. The power of arbitral tribunal under sub-section (3) includes the power to determine admissibility, relevance materiality and weight of evidence.

49

Arbitration Act 1996

5.3 Section 20- Place of Arbitration

(1) The parties are free to agree on the place of arbitration. (2) Failing any agreement referred to in sub-section (1), the place of arbitration shall be determined by the arbitral tribunal having regards to the circumstances of the case, including the convenience of the parties. (3) Not withstanding sub-section(1) or sub-section(2) , the arbitral tribunal may unless otherwise agreed by the parties , meet at any place it considers appropriate for consultation among its members, for hearing witnesses, experts or the parties, or for inspection of documents , goods or other property.

Article 20_UNCITRAL Model Law

(1)The parties are free to agree on the place of arbitration. Failing such agreement, the place of arbitration shall be determined by the arbitral tribunal having regards to the circumstances of the case, including the convenience of the parties. (2) Not withstanding the provisions of paragraph 1 of this article, the arbitral tribunal may, unless otherwise agreed by the parties, meet at any place it considers appropriate for consultation

50

Arbitration Act 1996 among its members, for hearing witnesses, experts or the parties, or for inspection of goods, other property or documents.

Section-21-Commencement of arbitral proceedings

Unless otherwise agreed by the parties, the arbitral proceedings in respect of a particular dispute commence on the date on which a request for that dispute to be referred to arbitration is received by the respondent.

Article 21-UNCITRAL model law

Unless otherwise agreed by the parties, the arbitral proceedings in respect of a particular dispute commence on the date on which a request for that dispute to be referred to arbitration is received by the respondent.

IN BRIEF:-

This section provides that where the arbitration agreement is silent about the date of commencement of the arbitration proceedings, the proceedings will be deemed to have

commenced on the date of receipt of the notice requesting reference to arbitration, by the respondent

51

Arbitration Act 1996 5.5 Section 22-Language

(1) The parties are free to agree upon the language or languages to be used in the arbitral proceedings. (2) Failing any agreement referred to in sub-section (1), the arbitral tribunal shall determine the language or languages to be used in the arbitral proceedings. (3) The agreement or determination, unless otherwise specified, shall apply to any written statement by a party, any hearing and any arbitral award, decision or other communication by the arbitral tribunal. (4) The arbitral tribunal may order that any documentary evidence shall be accompanied by a transaction into the language or languages agreed upon by the parties or determined by the arbitral tribunal.

Article 22-UNCITRAL Model Law

(1) The parties are free to agree on the language or languages to be used in the arbitral proceedings. Failing such agreement, the arbitral tribunal shall determine the language or languages to be used in the proceedings. This agreement or determination, unless otherwise specified therein, shall apply to any written statement by a party, any hearing and any award decision or other communication by the arbitral tribunal. 52

Arbitration Act 1996 (2) The arbitral tribunal may order that any documentary evidence shall be accompanied by a transaction into the language or languages agreed upon by the parties or determined by the arbitral tribunal.

IN BRIEF:-

This section deals with the subject of language to be used in arbitral proceedings. Language aspect assumes importance in view of ever widening horizons of trade and commerce-national as well as international.

The parties are left free to agree upon the language or languages to be used in the arbitral proceedings. In the absence of agreement, the arbitral tribunal will determine the language or languages to be used. The agreements of the parties or the determination by the arbitral tribunal on the point unless otherwise specified, shall apply to a written statement by a party, hearing , award , decision or any other communication by arbitral tribunal.

Sub-section (4) empowers the arbitral tribunal to order that any documentary evidence shall be accompanied by transaction into

53

Arbitration Act 1996 the language or languages agreed upon by the parties or determined by the tribunal.

5.6 Where is the Award to be filed Section 31 of Arbitration Act

This would require consideration as to which court would have jurisdiction in the matter. Section 31 of the arbitration act is relevant for that purpose. It reads as under:

(1) Subject to the provision of this act, an award may be filed in any court having jurisdiction in the matter to which the reference relates.

(2) Notwithstanding anything contained in any other law for the time being in force and save as otherwise provided in this act, all questions regarding the validity, effect or existence of an award or an arbitration agreement between the parties to the agreement or persons claiming under them shall be decided by the court in which the award under the agreement has been, or maybe, filed, or by no other court.

(3) All

application

regarding

the

conduct

of

arbitration

proceedings or otherwise arising out of such proceedings shall

54

Arbitration Act 1996 be made to the court where the award has been or maybe, filed, and to no other court.

(4) Notwithstanding anything contained else where in this act or in any other law for the time being in force, where in any reference any other application under this act has been made in a court competent to entertain it, that court alone shall have jurisdiction over the arbitration proceedings and all subsequent application arising out of that reference and the arbitration proceedings shall be made in that court and in no other court.

This section was added on the recommendation of Civil Justice Committee (1924-1925) which said that what seems to be most required is that in the case of every arbitration one court and one only should be the forum in which all questions relating to the validity of the award should be finally determined

This section is not an enabling provision but one which defines jurisdictions for applications under the Act. In this regard it is relevant to bear in mind that,

(a) the award maybe filed in any court having jurisdiction to entertain a suit with respect to the subject matter of the reference ,

55

Arbitration Act 1996 (b) all questions relating to the validity , effect , or existence of an award or an arbitration agreement as between the

(c) parties or their privies are to be decided by the court in which the award has been filed, (d) all applications relating to the conduct of arbitration proceedings or arising out of the same are also to be filed in the court as in (b) , and (e) once an application has been filed in a court of competent jurisdiction to entertain all subsequent applications with respect to the same arbitration throughout.

56

Arbitration Act 1996

6 CASES

6.1 . Olympus Superstructures Pvt.Ltd. vs. Meena Vijay Khetan (Challenge to jurisdiction of arbitrator under Section 16)

Case Reference: Civil Appeals Nos.2912-2914 of 1999, decided on May 11, 1999.

Judges: Justice M.Jagannadha Rao and Justice S.N.Phukan

Parties: Olympus Superstructures Pvt.Ltd.(Appellant)Vs. Meena Vijay

Khetan and others(Respondents).

Question of Law: (i) When questions regarding jurisdiction of Arbitrator and scope of reference to Arbitrator are not raised under Section 16 of the Act of 1996, whether they can be raised subsequently at the stage of challenge to the award under Section 34 of the Act of 1996. (ii) Whether disputes relating to specific performance of contract can be referred to arbitration.

57

Arbitration Act 1996

Gist of the Case: The Appellant executed three main agreements for sale of flats and also three other separate Agreements (hereinafter called the Interior Design Agreements) with the Respondents. Later,

disputes and differences arose between them in respect of these agreements. The Respondents issued a notice to the Appellant for referring their disputes for arbitration to one out of three retried Judges suggested by them. As the Appellant failed to reply agreeing for arbitration, the Respondents moved the Court for interim protection before filing a regular petition under Section 11 of the Act of 1996 for appointment of an Arbitrator. A retired Chief Justice of Bombay High Court was appointed as Sole Arbitrator to adjudicate the dispute. The Respondents filed their claim before the Arbitrator but the Appellants took several adjournments. The Arbitrator took up the matter for evidence and thereafter passed the award granting relief of specific

performance in respect of the three main Agreements and also in respect of the three Interior Design Agreements. The Appellant challenged the three awards under Section 34 of the Act of 1996 by filing three applications which were dismissed by a single Judge and later by a Division Bench of the Bombay High Court. It is against these Judgements the present appeals have been field.

58

Arbitration Act 1996

The Appellant contended that reference to arbitration was based on the three main agreements and therefore the Arbitrator could not have decided the disputes regarding the other three Interior Design Agreements; the arbitration clauses in the main

agreements could not supersede the separate arbitration clauses under the Interior Design Agreements which provided for named Arbitrators; an Arbitrator could not grant specific performance of an agreement and hence Section 34 (2) (b) (i) of the Act of 1996 was attracted; the Respondents committed default in payment of the agreed amounts in respect of the three main agreements and therefore termination of the contract was valid and the

Respondents should be directed to pay interest on the balance amount at a rate of 21% . The Respondents contended that under the arbitration clause in the main agreement, it was permissible to refer to the arbitrator not only disputes and differences under the main agreement but also in respect of connected matters; the Appellant never raised any objection relating to jurisdiction under Section 16 of the Act of 1996 that the Arbitrator could not decide the dispute concerning the Interior Design Agreements and that objection was not raised even before the learned Single Judge of the Bombay High Court; for the first time the objection was raised

59

Arbitration Act 1996

before the Division Bench of the Bombay High Court; these objections could not be raised after the passing of the award; an

Arbitrator could grant specific performance of an agreement of sale; it was prayed that the appeals be dismissed. The Supreme Court observed that the Appellants filed their written statement but no objection was raised that the disputes and differences contained in the three Interior Design

Agreements were not intended to be referred to the arbitrator or that the same could not be decided by the Arbitrator appointed under the main agreements. The Appellants counsel had crossexamined the Respondents witnesses upto a stage and even then no such objection as to scope of reference was raised. The Arbitrator referred in his award to the sole contention of the Appellant before him was that the Interior Design Agreements, were void inasmuch as no amount was paid at the time of the agreements, though Rs10 lakhs each was agreed to be paid. No dispute as to the power of the Arbitrator to deal with the disputes under the Interior Design Agreements was raised, which meant that the Appellant accepted that the disputes under the Interior Design Agreements were also covered by the reference. In the objections to the award filed in the Court under Section 34

60

Arbitration Act 1996

of the Act of 1996 no such point was raised except a general ground that entire proceedings of arbitration were illegal, bad in law and that the award was liable to be set aside. Even before the Single Judge the above mentioned objections were not raised by the Appellant. For the first time, the point relating to the

scope of reference was raised before the Division Bench and the same was rejected. The Supreme Court observed that it agreed with the

Respondents contention that if the parties before the arbitrator had any objection to the Arbitrators jurisdiction the same should have been raised before the Arbitrator as provided in SubSections (2) and (3) of Section 16 of the Act of 1996. Sub-Section (5) of Section 16 requires the Arbitral Tribunal to decide on the plea referred to in Sub-Section (2) or (3) at that stage itself and if the pleas are rejected by the Arbitral Tribunal, it will continue with the arbitral proceedings and make the arbitral award. The party aggrieved by such an arbitral award may make an application to set aside the arbitral award under Section 34 of the Act of 1996. The learned Judges observed that clause 39 of the main agreement permits reference to arbitration not only of issues 61

Arbitration Act 1996

arising under the main agreement but also those disputes or differences which are connected with the disputes under the main agreement. There were several items in Schedule E of the main agreement which overlapped with items in schedule A of the Interior Design Agreement. The date of main agreement and Interior Design Agreement is the same and clause 3 of the Interior Design Agreement states specifically that the work of

the said renovation, designing and installation shall commence from the execution thereof which means that the execution of the Interior Design Agreement and the main agreement is to be simultaneous. If there is a situation where there are no disputes arising from the main agreement but there are disputes arising from the Interior Design Agreement, only then the arbitration

clause 5 of the Interior Design Agreement comes into play. Whereas, in the present case, there are disputes in respect of the main agreement as well as the Interior Design Agreement. Hence, under clause 39 of the main agreement arbitration can take place to cover the disputes of the main agreement as well as the Interior Design Agreement.

62

Arbitration Act 1996 On the point, whether disputes relating to specific performance of a contract can be referred to arbitration, the Supreme Court observed that the right to specific performance deals with contractual rights and it is certainly open to the parties to agree with a view

to shorten litigation in regular courts to refer the issues relating to specific performance to arbitration. There is no prohibition in the Specific Relief Act, 1963 that issues relating to specific performance of contract relating to immovable property cannot be referred to arbitration. Nor is there such a prohibition in the

Act of 1996. The factual points in the present case do not fall under Section 34 (2) (b) of the Act of 1996, i.e. (i) the subject-matter of the dispute is not capable of settlement by arbitration under the law for the time being in force, or (ii) the arbitral amount is in conflict with the public policy in India. For the aforesaid reasons, the appeals were dismissed without costs 2. Konkan Railway vs. Rani Construction (A Constitutional Bench has decided that the order of the Chief Justice or his designate in appointing an arbitrator under Section 11 of the Act of 1996 is administrative in nature)

63

Arbitration Act 1996 Case Reference: Civil Appeals Nos. 5880-5889 of 1997 with C.A. Nos.713-716, 2037-2044, 4311-4312, 4324, 4356, 7304 and 7306-7309 of 1999. D/-30-1-2002. .

Judges: Justice S.P.Bharucha, C.J.I. and 4 other Judges

Parties: Konkan Railway Corpn. Ltd. and another (Appellants) Vs. Rani Construction P.Ltd. (Respondent).

Question of Law: Whether the order of the Chief Justice or his designate under section 11 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 (for short, Act of 1996) nominating an arbitrator is a judicial order or an administrative order and whether such an order can be appealed against under Article 136 of the Constitution.

Gist of the Case: Section 11 of the Act of 1996 deals with the appointment of arbitrators. It provides that the parties are free to agree on a procedure for appointing an arbitrator or arbitrators. In the event 64

Arbitration Act 1996 of there being no agreement in regard to such procedure, in an arbitration by three arbitrators each party is required to appoint one arbitrator and the two arbitrators so appointed must appoint the third arbitrator. If a party fails to appoint an arbitrator within thirty days from the request to do so by the other party or the two arbitrators appointed by the parties fail to agree on a third arbitrator within thirty days of their appointment, a party may request the Chief Justice to nominate an arbitrator and the nomination shall be made by the Chief Justice or any person or institution designated by him. If the parties have not agreed on a procedure for appointing an arbitration in an arbitration with a sole arbitrator and the parties fail to agree on an arbitrator within

thirty days from receipt of a request to one party by the other party, the nomination shall be made on the request of a party by the Chief Justice or his designate. Where an appointment procedure has been agreed upon by the parties but a party fails to act as required by that procedure or the parties, or the two arbitrators appointed by them, fail to reach the agreement expected of them under that procedure or a person or institution fails to perform the function entrusted to him or it under that procedure, a party may request the Chief Justice or his designate to nominate an arbitrator, unless the appointment procedure provides other means in this behalf. The decision of the Chief Justice or his designate is final. In nominating an arbitrator the 65

Arbitration Act 1996 Chief Justice or his designate of the must have in regard the to the

qualifications

required

arbitrator

agreement

between the parties and to other considerations that will secure the nomination of an independent and impartial arbitrator. The Supreme Court observed that there is nothing in Section 11 that requires the party other than the party making the request to be noticed. It does not contemplate a response from that other party. It does not contemplate a decision by the Chief Justice or his designate on any controversy that the other party may raise, even in regard to its failure to appoint an arbitrator within the period of thirty days. That the Chief Justice or his designate has to make the nomination of an arbitrator only if the period of thirty days is over does not lead to the conclusion that the decision to nominate is adjudicatory. In a given case, if a party has justifiable doubts about the independence and impartiality of the arbitrator appointed by the Chief Justice or his designate, it is open to such party to challenge the arbitrator under Section 12 of the Act of 1996, adopting the procedure laid down in section 13.Even in a case where the Chief Justice or his designate has appointed an arbitrator before the expiry of the prescribed period of 30 days, it

66

Arbitration Act 1996

is open to the aggrieved party to challenge the jurisdiction of the arbitrator and such a challenge may be decided by arbitral tribunal itself under Section 16. The Supreme Court observed that the schemes made by the Chief Justices under section 11 cannot govern the interpretation of Section 11. To the extent that the Chief Justice of India scheme, 1996 goes beyond Section 11 by requiring, in Clause 7, the service of notice upon the other party to the arbitration agreement to show cause why the nomination of an arbitrator, as requested, should not be made, it is bad in law and must be amended. The Supreme Court also observed that although the UNCITRAL Model Law and Rules of Arbitration have been taken into account for drafting the Act of 1996, they are not identical and hence the UNCITRAL Model Law and Judgements and literature are not a guide to the interpretation of the Act of 1996 and especially of Section 11 thereof. Article 136 of the Constitution of India empowers the Supreme Court to grant special leave to appeal any judgement, decree, sentence or order in any cause or matter passed or made by any

67

Arbitration Act 1996 court or tribunal in the territory of India. The Supreme Court held that since the order of the Chief Justice or his designate acting under Section 11 nominating an arbitrator is not an adjudicatory order and the Chief Justice or his designate is not a tribunal, such an order cannot properly be made the subject of the Petition for special leave to appeal under Article 136 of the Constitution of India.

3. Narayan Prasad Lohia vs. Nikunj Kumar Lohia and others ( In terms of Section 10 the number of arbitrators shall not be an even number. The parties to a dispute appoint two arbitrators and participate in the arbitral proceedings. Is the award

delivered by the two arbitrators valid in law ) Case Reference: Civil Appeal No.1382 of 2002, decided on 20/2/2002.

Judges: Justice G.B.Pattanaik, Justice S.N.Phukan and Justice S.N.Variava Parties: Narayan Prasad Lohia (Appellant) Vs Nikunj Kumar Lohia and others (Respondents) Question of Law: 68

Arbitration Act 1996 The parties to a dispute appoint two Arbitrators to adjudicate their dispute and participate in the arbitration proceedings. The two Arbitrators pass an award thereafter. In terms of Section 10 of the Act of 1996 there cannot be even number of Arbitrators in arbitration. Is the award passed by the two Arbitrators valid in law?

Gist of the Case: The Appellant and the Respondents are family members who had disputes and differences in respect of family business and properties. They agreed on 29/9/1996 to have their disputes and differences resolved through two persons. The parties made their respective claims before these two persons. All parties

participated in the proceedings. On 6/10/1996 an award was passed by the said two persons. The 1st and 2nd Respondents challenged the award on the ground that the arbitration was by two arbitrators whereas under

the Act of 1996 there cannot be an even number of arbitrators. A Single Judge of the Kolkata High Court set aside the award dt.6/10/1996. The appeal filed in the High Court was also dismissed. Hence this appeal to the Supreme Court.

69

Arbitration Act 1996

In terms of Section 16 of the Act of 1996, the Arbitral Tribunal can rule on any objection with respect to existence or validity of the arbitration agreement. It has been held by a Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court in the case of Konkan Raily Corpn.Ltd. vs. Rani Construction Pvt.Ltd. that the authority of the Arbitral Tribunal under Section 16 is not confined to the width of its jurisdiction but also goes to the root of its jurisdiction. It is no longer open to contend that, under Section 16, a party cannot challenge the composition of the Arbitral Tribunal before the Arbitral Tribunal itself. However, such a challenge under Section 16(2) must be taken not later the submission of the statement of defence. Section 16(2) makes it clear that such a challenge can be taken even though the party may have participated in the appointment of the arbitrator and/or may have himself appointed the arbitrator. Needless to state that a party would be free, if it so chooses, not to raise such a challenge. Thus a conjoint reading of Sections 10 and 16 shows that an objection to the composition of the Arbitral Tribunal is a matter which is derogable. It is derogable because a party is free not to object within the time prescribed in Section 16(2). If a party chooses

70

Arbitration Act 1996