Professional Documents

Culture Documents

NO TITLE YET (The Story of First Lieutenant Maurice "Tex" Hughett)

Uploaded by

Dianne BishopOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

NO TITLE YET (The Story of First Lieutenant Maurice "Tex" Hughett)

Uploaded by

Dianne BishopCopyright:

Available Formats

(NO TITLE YET) Author unknown. Date written unknown. Edited and translated to electronic format by Dianne Bishop.

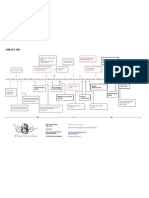

[Editors note: This manuscript was given to me by my Dad, who was given it by his Dad. This true story is about one of my Dads cousins. The manuscript was hand-typed on an old typewriter, and I was told was written for a book that was never finished. It was replete with spelling and grammatical errors, which have been corrected to the best of my ability.] In mid-March 1942 the Philippine and American troops on Bataan were trapped. Cut off from outside help, and with Japanese forces pushing relentlessly forward, the Allies were doomed to fighting it out until the bloody end. Escape from Bataan was a dream beyond reason, but destiny contrived to propel an Army Air Force pilot, First Lieutenant Maurice "Tex" Hughett, on an unscheduled boat ride, away from eventual death or capture on Bataan, into three and a half years of astounding adventures. There were about 5,000 U.S. Army Air Force pilots, air crewmen and support personnel on Bataan. Most of their planes having been destroyed and all but a few, still operational, withdrawn to safer airdromes in the Netherlands East Indies, these men were issued rifles and called upon to fight as infantry. Men of the 17th Pursuit Squadron, to which Maurice Hughett was attached, were no exception. At this moment in time, about 200 men of the 17th Pursuit Squadron were dug in along several hundred yards of beach on the west coast of Bataan to repel Japanese troops attempting to land and infiltrate behind Allied lines. Getting supplies to these troops from Mariveles, on the southern tip of the peninsula, over mountainous jungle trails posed a very difficult problem, and was tortuously being accomplished by using mules and men to pack them in. To expedite the movement of supplies, Maurice Hughett was put in charge of the operation. He immediately improved the procedure by scrounging a 36 foot motor launch from the Navy, and began moving supplies from Mariveles harbor past the fortress of Corregidor, and up the coast to the area held by the 17th. Maurice used his boat only at night as Japanese aircraft combed the area during daylight hours like killer bees, attacking anything that moved. To get safely past the Corregidor's guns a daily identification code, changed every few hours, was worked out. Even so, one night a triggerhappy gun crew fired three 5 inch rounds at them, which fortunately missed. On the night of March 13, 1942, Maurice, a Corps of Engineers Captain named Ralph Fralic, and three Air Force Sergeants; I.A. White, Charles Heald, and Stoddard, unloaded their supplies and where heading back when, about a mile off shore, the engine quit. Frantically, they tried everything they could think of to restart the pesky old engine, but nothing worked. A strong off shore wind was blowing and, when the sun came up, Maurice and his crew found themselves out of sight of land, and alone in the vast South China Sea. There was no way in the world they could get back to Bataan. Even if they could, they didn't know the current recognition signal to prevent coast defense guns, that zeroed in on anything moving on the sea,

from blowing them into another world. After discussing their situation, it was decided to sail in a northwesterly direction and try to hit the nearest land, which was on the China coast near Canton. Survival was their primary objective, but they hoped to land where no Japanese troops were stationed, and make their way inland to meet up with the forces of Chiang Kai-shek. As the crow flies, that would be a distance of more than 5OO miles over open water. The fact that they had on board only a small cask of water and about a three day supply of C rations made no difference - it was the best bet they had. Maurice was designated to do the navigating using a small binnacle, with which the launch was equipped, and a small map. Jury rigged sails made of two ground sheets were hoisted on a mast fashioned from boards ripped from the launch's flooring. With a lusty wind pushing them in the projected direction, the men, taking turns at the tiller, settled down with high hopes of success. Food and water were sparingly rationed, even so, on the fourth day both were depleted. The sun, ho' as a branding iron, bore down on the hapless men to add sunburn and thirst to their problems. The next two days without water were sheer agony but, on the seventh day they were drenched by torrents of rain as a typhoon vented its fury upon them. The little launch rolled and pitched, and at times seemed on the verge of capsizing. Everyone but Maurice became violently seasick. Yet, all hands were forced to continually bail out water from waves breaking over them and the rain which never ceased. For three days and nights freakish winds battered the launch and its desolate crew and, when it had blown itself out, no one knew where in the hell they were. Added to that, the wind was now coming briskly from the east forcing abandonment of any thought of reaching China, for the heavy launch, lacking a centerboard -and adequate sails, could not be made to tack. To reach land at all it was determined they must now accept whatever course the wind would allow. This meant sailing due west, and pray the wind held long enough to bring them to the coast of French Indochina. If they missed and were pushed further south, they could end up in the Gulf of Siam or simply remain in the South China Sea where, in either event, their chances of survival were grim. For the next ten days a favorable wind carried them westward. The water cask, filled during the typhoon, was replenished twice by fortuitous rain squalls. Their only food consisted of several flying fish which bounded out of the sea into the boat to be immediately ripped apart and devoured raw. In all this time they had sighted no ship or any sign of land, but that morning the five castaways, with unbounded joy, sighted land lying low on the western horizon. It took several long agonizing hours before the launch finally drifted up on a sandy beach. Before it did, however, Japanese planes could be seen taking off and landing at an airfield several miles away. As soon as they could, all hands, motivated by the knowledge that Japanese troops infested the area, scrambled out of the boat and hurriedly took shelter in some nearby hills. From a hilltop the men saw before them a huge bay, across which to the south was a large city. Maurice, now certain they had landed in French Indochina, correctly determined that the

city was Tourane, later to be named De Nang. This meant they were well over six hundred miles on a straight line from Bataan, but to get there he figured they must have traveled more than a thousand miles in the open sea. Below them, and not far away, was a small island connected to the mainland by a short causeway. It appeared to be a minor seaplane base containing a small hanger and a few nondescript buildings. After studying this place for some time and sighting only a French officer and several native troops, but no Japanese, Maurice decided to bite the bullet and go there to seek help. Accompanied by one of the sergeants, while the others remained in hiding, Maurice warily made his way to the causeway. On approaching the entrance to the base, Maurice noted native soldiers moving to intercept them, and he hailed the French officer. a Lieutenant. It turned out that the Lieutenant didn't understand English, and what little French Maurice had been exposed to in high school had long ago gone down the drain. When the Lieutenant finally got the idea that they were Americans, he took them to a small building to meet a French Captain who spoke English. The Captain, understandably, was dumbfounded to learn they had come all the way from the Philippines. When Maurice asked what would happen to them, he replied that they would be interned by the French. This sounded infinitely better than falling into Japanese hands, and Maurice signaled the others to come down from the hills. It was then that Maurice learned they had landed on the tip of a small peninsula, and the city on the other side of the bay, as he had figured, was indeed Tourane. The Captain also told him that soon after France fell to the Germans, the Japanese demanded that their troops be permitted to occupy Indochina peacefully on July 24, 1941 or they would do so by force. The puny French Colonial Forces, scattered throughout the country, being no match for the powerful Japanese war machine, left the Vichy government no alternative but to acquiesce. As a result, the French still maintained their bases, which posed no threat to the Japanese, and some semblance of government. They were free to move about as they pleased so long as they minded their own business and kept out of the Jap's way. This particular base had a complement of two officers and about twenty native, or French Colonial Army troops. The Americans were treated most cordially, and were quickly taken into a dining hall where they were served scrambled eggs, bananas , milk and bread. Although famished, the men were eating slowly, for it was suggested they be careful after having gone so long without food, when the door suddenly burst open and the room filled with Japanese soldiers waving pistols and swords, and yelling like a pack of deranged hyenas. The Americans were brusquely made to surrender and were taken by speedboat to Kempeitai (Military Police) headquarters in Tourane, and imprisoned . The French were incensed and embarrassed by this blatant Japanese intrusion in their supposed area of command, but were powerless to do anything about it. Some months later the French apologized to Maurice and explained what had happened. It seems that when the arrival of five Americans was phoned to French headquarters in Tourane, the Lieutenant who took the

call immediately notified the Japanese without first informing his commanding officer. From that day on, the unfortunate Lieutenant was ostracized, or as the British would say, " Sent to Coventry, by his fellow officers. For the next three days, the Americans were kept in the Tourane jail. Then, because there was no interpreter there, they were taken by rail to Hanoi, about 450 miles to the north. Locked up in a wooden building, infinitely better than the Tourane jail, the men were questioned almost daily for nearly a month. The Japanese refused to believe they had come from the Philippines in an open boat, and accused them of being spies or saboteurs for which they would be shot. Over and over again they answered the same general questions about Bataan, which by this time had fallen, until the Japanese decided to send them south for further questioning. The Americans were put into a chair car and shipped more than 900 miles south by slow freight to the Cholon prison, just outside of Saigon. Here they were tossed into a concrete dungeon, about 10 feet by 14, with a door no more than 2 feet square. A dim light bulb, hanging overhead, was kept lit at all times. A small wooden tub , emptied once a day, served as their toilet. In this grim place, run by the infamous military police known as the Kempeitai, the Americans were again subjected to the same line of questioning as in Hanoi. Many times they were told they would be beaten if caught lying, but the questions were so inane there was no reason to lie and they were never punished. The anguished screams of other prisoners being tortured there, however, often reverberated through the dank cell blocks to provide sobering proof that the Japanese were not adverse to playing dirty hard ball. The Japanese who interrogated the Americans wore an army uniform without insignia, and spoke impeccable English. Although his attitude was one of aloofness, he evinced no animosity. Once, when Maurice asked where he learned to speak such good English, the man blandly replied that he had graduated from UCLA. He refused to elaborate on the subject, and coolly let Maurice know that he would answer no more questions. It is entirely possible that the five Americans, whose lives were in jeopardy when it came to the Japanese either believing their story or judging them to be spies, were beholden to this UCLA graduate far more than they would ever know. While in Cholon, the Japs brought in a Flying Tiger pilot named Lewis S. Bishop. Flying a P-40 fighter, he was bombing and strafing Lao Kay in northern Vietnam when fragments from his own bomb struck his plane, forcing him to bail out. Maurice had only one brief opportunity to talk with Bishop. He never learned what finally happened to him. In early August 1942, the Americans were transferred to a large prisoner of war camp situated near the docks in Saigon. Confined here were one thousand British troops and twenty of their officers captured with the fall of Singapore. Contrasted with the British, who had managed to bring with them most of their personal belongings, the bearded Americans, with long matted hair, and filthy clothing looked like wings picked up in some back alley. The first order of business for the newcomers was a long overdue bath, a shave, haircut and the scrubbing of clothes. That done, the meets spirits, which confinement in the Cholon dungeon coupled with the

terrible uncertainty about what the Japanese planned to do with them had all but shattered suddenly blossomed anew. Maurice and Fralich were assigned to the barracks set aside for officers. Like the other buildings housing prisoners, it was constructed of bamboo with nipa palm sides and roof. The British cordially greeted the Yanks, and did their best to make them comfortable. The war news, which the British obtained from French and other sources, was discouraging. During the first week of May, General Wainwright had surrendered Corregidor and all of his forces throughout the Philippines. At about the same time the Americans, in the Battle of the Coral Sea, had thwarted a Japanese thrust towards Australia, and in early June had decimated a powerful Japanese invasion force at the Battle of Midway, nevertheless, the enemy now was in complete control of all Southeast Asia, including Burma. With the nearest Allied troops more than 2,000 miles away, escape from Saigon was considered impossible. More important at the moment, however, was the information that food consisted of rice three times a day, along with a watery soup which was occasionally embellished with fish heads cast off by their captors. The prisoners could augment their rations by purchasing a few duck eggs, bananas, and small rice cakes from a Japanese civilian who once a week brought the stuff into camp in a horse drawn cart. Money for this exchange came from the pay prisoners received from the Japs, which amounted to ten cents for enlisted men, and twenty to forty cents a day for officers, depending upon their rank, but the wily POWs were quick to come up with another way to raise money. Forced to work on the docks, loading and unloading ships, many prisoners began to make it pay off by simply stealing anything of value they could lay their hands on, and selling it for cash to natives. Anyone caught in the act was severely beaten and, more often than not, thrown into solitary confinement on starvation rations, but this did little to deter others from continuing as before. At one point the Japanese figured out that the prisoners were spending more money than they were being paid, and all hell broke loose. Senior officers were marched under guard to prison headquarters and were subjected to intensive questioning, during which they were punched and slapped around. All the while they pleaded innocent, contending the money paid to the Japanese vendor for extra food came from selling off some of their personal effects. Aware of the ample amount of gear many British POWs had brought with them from Singapore, the Japanese finally, but reluctantly, accepted the excuse. This camp was no bed of roses for the Japanese were quick to inflict severe punishment on the prisoners for even minor infractions of rules. Sometimes prisoners were punished for no reason at all. Soon after his arrival, Maurice witnessed one such incident when a young British soldier was unmercifully beaten. When Maurice asked the camp interpreter what had caused the beating, he was told that the lad had walked past some Japanese soldiers who could tell by the look in his eyes that he was having evil thoughts about them. If that was the case, Maurice concluded. the Japanese could kill all of them. Japanese sergeants came into camp daily and took out labor gangs consisting of 100 prisoners each to work on the docks loading and unlaying ships. These included one officer who was responsible for the work performed. After several weeks of this, one of the sergeants took a

liking to Maurice and, whenever he was on duty, selected him an the officer for his group. In times the sergeant permitted Maurice certain small liberties that few other prisoners enjoyed. On several occasions he even sneaked Maurice over to a small cafe near the docks to buy him a beer. Now it seems that Maurice had only one shirt to his name. It was a fancy tailormade job by a Filipino who had embroidered upon it his officers insignia. and pilot's wings. The sergeant was so impressed with this fancy shirt that he offered to buy it. Maurice, however, with embers of escape smoldering in his mind and aware that he could easily pick up an old work shirt, refused to sell, but conned the guard into swapping it for a pair of white walking shorts and white shirt identical to those worn by the French civilians. The sergeant, disdainful of any prisoner's chance of escaping from Saigon was delighted with the deal, and Maurice stashed his new clothing away until he figured out how it could be used. In early November 1942, the sergeant marched Maurice and his men about a mile away from the docks to a large, brush covered field which they were put to work clearing for a Japanese garden. Bordering one side of this land, but separated from it by a hedge row, were houses occupied by French civilians. It wasn't until the third day of working in the area that Maurice caught a glimpse of a man behind one of the houses. Noting that the Sergeant was occupied at the other end of the field, Maurice casually strolled over to the hedge and in a hushed voice attracted the Frenchman's attention. During the course of a necessarily brief conversation, he learned that the man, Lucien Goudard, who spoke excellent English, had been head of the John Deere Corporation's Saigon office. Goudard wanted to know how he could help the prisoners, and Maurice told him there was a desperate need for medicine in the camp to treat malaria and other tropical diseases, as well as medical supplies in general. Goudard quickly promised to get hold of the needed supplies, but noted that moving them into the camp past the Japanese would pose a problem. Nevertheless, he would do his best to figure out how to overcome that obstacle. Then Maurice, elated over his fortunate meeting with Goudard but fearful of attracting the guard's attention, cut short the conversation and slowly walked away. The next day Maurice was back working on the docks which stopped further contact with his new found friend, but he remained confident that Goudard would keep his promise. When three weeks passed, however, without any signs of the needed medical supplies, Maurice decided upon an extremely dangerous venture. Well aware of the terrible punishment he would receive if caught, Maurice decided to slip out of camp and visit the Frenchman. The prison compound was surrounded by rows of high barbed wire fence inside of which Korean guards continually patrolled. For some time Maurice had been studying how he might escape from the camp, and noted that one section of the wire enclosure had a small hut at either end which, when the guard turned the corner, prevented him from seeing the area he had just patrolled. It also took just over a minute before another guard appeared to pace the same dimly lit route. With a little luck, this would give him time enough to scurry beneath the fence and vanish into the shadows. To facilitate crawling beneath the lowest strand of barbed wire, which was drawn tight just a few inches above the ground, Maurice stealthily loosened dirt so it could be quickly scooped out and replaced. To assist in the escape try he enlisted two other prisoners. One was to

signal with a small lamp when the guard had turned the corner, the other to lift the barbed wire strand and replace the scooped out dirt. As planned, it was a moonless night when Maurice, wearing the recently acquired white shorts and shirt beneath his flight suite (coveralls), and his cohort furtively moved towards the fence. When the guard was ten paces past the escape point, the two men sped to it and commenced digging, When the light signaled the guard was rounding the corner, Maurice squirmed his way under the wire of the lower fence and over the second, and in a matter of seconds was outside the camp and lost in the gloom of night. Maurice removed his flight suit as soon as possible and hid it beneath a pile of rocks. Clothed like a Frenchman he ambled down the street, hailed a rickshaw and went to Lucien Goudards house. The Frenchman, answering the knock on his door, failed to recognize this unexpected caller, and asked who he was and what he wanted. When Maurice identified himself and Lucien suddenly realized that before him was the American prisoner with whom he had previously talked, his eyes bulged wide in utter astonishment. "Oh, my God!", he exclaimed, and literally pulled Maurice into the house and closed the door. As the two men vigorously shook hands an instantaneous feeling of mutual respect passed between them. Maurice was elated when Goudard presented him with a large canvas bag filled with medical supplies, and some money to buy extra food for the sick which he and a few friends had collected, but had been unable to devise a means of getting into the camp. He promised more such supplies that would be ready for pickup whenever Maurice could return. The meeting was brief for Lucien would be in serious trouble should the Japanese find him consorting with a prisoner, and Maurice faced the problem of returning to camp with his loot intact. After thanking Lucien profusely for his invaluable assistance, Maurice returned to town in the rickshaw, paid the native driver, and went to where his flight suit was hidden. As soon as the flight suit covered kits white civies, Maurice cautiously moved towards the perimeter fence to lie in a clump of high grass assessing the situation. For some strange reason, he noted, the guards were more active than usual, and there seemed to be more of them-. This convinced him that an attempt to return via the way he came out could prove to be hazardous to his health, and he'd have to devise another way back. Choosing a propitious moment, he ran to the fence and heaved the bag of medicine over it. Two blinks of a light let him know that his waiting friends had retrieved the booty. Then Maurice quickly left the area and went to a nearby street along which he knew 300 POWs would soon be returning from stevedoring when their shift ended at midnight. He hid in the shadows of a deserted building and waited. Well aware that these work parties always consisted of ninty-nine men and one officer, Maurice, with no better alternative, decided to slip into the ranks of one of these parties, and pray the Japs would not spot him. The first group of one hundred marched by, stopped at the gate to be counted, and passed on into camp. When the second group came along Maurice waited until the Jap guard had passed then he eased out of the shadows and squeezed into line. At the gate when the Japs counted 101

prisoners they raised hell. Several more times they counted noses and still came up with the same answer. Finally, after much shouting at each other the Japs sent one man they thought was trying to get in early back to the third and last group, whereupon Maurice safely returned to camp. It is amusing to note that when the third group was stopped at the gate to be counted, there were of course 101 prisoners which instantly sent the Japanese into another flat spin. The British officer in charge of the group tried without success to soothe the Japanese soldiers by saying that prisoners often got sick and fall out then join up with another group . This, however, didn't add up as the two previous groups each had 100 prisoners, and there was still one too many. After a half hour of considerable shouting and recounting, the officer toad the Caps that he just learned that one of the men got sick and came in early. To this illogical and factitious explanation the Japanese said O.K. and passed the work party into camp. It was almost three months before Maurice, motivated by the camps lack of essential medicine decided to chance another visit to Goudard. This time everything went according plan, and Maurice returned with two large bags of medicine and more food money. Several weeks later Maurice was shocked to learn the he and the four other Americans would soon be transferred to a POW camp in Thailand. To be transferred just when he was beginning to know his way around and planning more extensive operations, Maurice, in desperation, was driven to seek the help of Doctor McLaughlin, one of two British doctors in camp. As they were good friends and Maurice the camp's only means of obtaining decent medical supplies, McLaughlin reluctantly agreed to lend a hand, because, as he told Maurice, the only thing he could do was risky and would make him very sick. The doctor's admonitions did nothing to deter Maurice who was determined to do anything to keep from being moved to Thailand. Accordingly, the night before the day of departure doctor McLaughlin injected Maurice with some dirty water from which he developed a very high fever and became much too sick to travel. The upshot was that the four other Americans went to Thailand, leaving Maurice to recover from a violent fever in two weeks, and become the only American in camp. In late 1943 Maurice was joined by 200 American POWs who had come from working as slave laborers on the Burma-Siam railroad, known as Death Railway2. One hundred of them were survivors of the heavy cruiser USS Houston sunk March 1, 1942 near Sunda Strait, Java, the lone officer was with the ninty-nine enlisted men from the 2nd Battalion, 131st Field Artillery of the Texas National Guard, all of whom had been captured with the fall of Java in March 1942. The lone officer in this group seemed vaguely familiar to Maurice. The prisoner was gaunt and he didn't appear to be in the best of physical condition, but Maurice suddenly recognized him as a former acquaintance who had attended Texas Tech University, named Ira Fowler. When the new prisoners were dismissed, Maurice walked over to him and said, Hello Ira, glad to see you." Fowler on the other hand blandly retorted that under the circumstances, he was a long way from being happy to see Maurice. Since he first ventured out of camp, Maurice had so refined the operation that, like a cat

burgler, he could sneak through the fence both ways with the Japs none the wiser, but this dangerous caper was not something he performed very often. In two years time Maurice was in and out of the camp eight times, and on the ninth he didn't come back. After three visits Maurice stopped going to Goudard's met home for there he had another Frenchman, Simon Petrie, who owned a resturant located near the docks which would serve as a more convenient meeting place. To facilitate setting up these meetings, Petrie introduced Maurice to "Sparks" Lienard, a French electrician, who held an important job on the docks. Lienard, who occasionally slipped Maurice money for food, passed information on to Petrie pertaining to the kind of medical supplies needed in camp and gave Maurice specifics about the next rendezvous. Although Maurice was dressed like a French civilian and spoke passable French, meetings at Simon Petrie's place were not without their hairy moments. Twice while Maurice sat at the bar with Petrie and his wife enjoying a beer, Japanese officers entered the restaurant to sit at a nearby table doing the same thing. Maurice never claimed or acknowledged any sort of a hero's role for his out of camp activities, but simply maintained that the food and drink were well worth the risk. In early October 1944 Maurice astounded Lucien Goudard and Simon Petrie by announcing that he was damn tired of being a Jap prisoner of war, and asked them to help him escape. Both men were quick to point out that to attempt to go east or south via the sea, or west through the wilds of Japanese occupied Cambodia would be sheer suicide. The only possible escape route would have to be road along the east coast which parallels the South China Sea. The catch here, though, was that Japanese troops occupied every major city and town along the route. Besides, if caught, the compassionless Japanese would undoubtedly put him to death. It was also pointed out that his chance of reaching Allied lines by hiking hundreds of miles alone through wild, uncharted lands lay far beyond the realm of possibility. Undeterred by this, Maurice stoutly insisted that given an area far removed from the Japanese, where he could have time to plot his next moves, he would make it all the way. He was so self-confident and so obsessed with the desire to get the hell away from the Japs that his friends promised to do what they could to help him escape. During the next several weeks, while plans were being formulated, Maurice kept in touch with Goudard and Petrie via his go-between "Sparks" Lienard whom he covertly met on the docks. In mid-December word was passed to Maurice that the escape was scheduled for the night of the 24th. Accordingly, on Christmas Eve of 1944 Maurice slipped under the prison fence for the last time. Dressed in his civilian clothes, Maurice went directly to the restaurant. Lucien Goudard and Simon Petrie were already there. Immediately he was spirited out the back door to find a man and a woman waiting for him in a Citron automobile. For security reasons no names were mentioned. Maurice never did know the man's name, but much later learned that the woman was Mme. L. Audibert, a key figure in the Free French underground. She had been instrumental in planning and executing his escape from Saigon and beyond. This was a dangerous game all

hands they were playing for if caught most assuredly would be put to death. Maurice was made to lie down on the floor in the back, covered with a blanket and, before he could bid goodbye to his friends, the car took off heading north. Once clear of Saigon Maurice removed the blanket but remained lying on the floor lest he be spotted by unfriendly eyes. They arrived at French owned coffee plantation , about 150 miles from Saigon, at dawn. Here they remained until dusk before venturing onto the main road bound for a tea plantation some 150 miles further north. Everything was moving along according to plan when a few hours before dawn and not many miles from their destination the car's engine suddenly gasped a few times and quit running. Unable to fix the thing they were forced to wait until daylight when another car driven by a Frenchman came along and towed them to a small village which fortunately boasted a so-called garage. Once again Maurice had no alternative but to lie motionless on the floor covered by a blanket. In the interim his two companions went to have breakfast while a native mechanic worked on the engine. Finally, after what for Maurice had been a torturous period of stifling heat, body cramps and sweat, the car was fixed and the trip to the tea plantation completed without incident. By this time, Maurice later learned, the Japanese had discovered he was missing, and to say that all hell had broken loose would be the understatement of the year. Prisoners were mustered every hour and counted - a procedure that continued for about a month -roadblocks were set up around Saigon and Korean guards dressed as civilians combed every part of the city eagerly seeking to nab the long gone American. Audibert and her companion headed back to Saigon the following day, leaving Maurice to await his next move in the escape plan. The plantation, he learned, encompassed a vast area far removed from terrain road. It was owned and managed by Frenchmen who lived there in several large houses. Maurice was accorded VIP treatment, and took full advantage of this opportunity to rest and gorge himself on delicious French cuisine - the first real food he'd been privileged to eat in over three years. As a diversion the plantation manager even took him on a Pheasant hunt. Soon after it occurred, word of the American's arrival had covertly been passed to French Army Headquarters in Hue, a large city about two hundred miles to the north. Accordingly, on his fifth day at the plantation, two French Army Lieutenants arrived in a Ford coupe with a uniform similar to their own for Maurice to wear, and it wasn't long before the Yank became a French Lieutenant look alike. The three men left the plantation late that afternoon to spend the night at a small French Army installation at Qui Nhon. They were up before dawn to hit the road for Tourane, a drive of about one hundred and seventy-five miles. Enroute they were stopped at several Japanese Army checkpoints, but if an escaped American was going Ought no trade of one could be found. If Maurice harbored misgivings about returning to the area, where some thirty-six months before he'd come ashore and rudely taken prisoner, they were quickly dispelled.

Although the Japanese operated from a large air base at Tourane and the area teemed with their troops, the French were permitted to maintain complete control over their military compound. Here Maurice was not only surprised by the warm cordiality of his welcome, but utterly flabbergasted to find himself the guest of honor at a banquet attended by French officers and hosted by none other than the Commandant. During the evening Maurice was targeted for an embarrassing number of apologies for having caused his capture and that of his friends. The blame was heaped upon the unfortunate young officer who notified the Japanese of their presence instead of his commanding officer. It would be different this time, Maurice was assured, the French would help him escape. Maurice was awakened early the next morning to discover that, for some reason known only to the French, he had been demoted to wearing the uniform of a sergeant. Following breakfast he was driven to the city of Hue about ninety miles north of Touran where the seat of the French Government for Indochina and French Army Headquarters were located. He was taken to a house on the city's outskirts where a French Army Sergeant was waiting with two bicycles. Then Maurice and the Sergeant peddled for nearly two hours right through the heart of the city, jammed with Japanese troops, natives and French civilians, to French Army Headquarters. Here again Maurice was warmly greeted by French officers, and was even invited to have tea with the Commanding General who promised to move him beyond the reach of Japanese troops. Although Maurice was at a loss to fathom why the French, under the awesome shadow of powerful Japanese forces, would take such risks to help a mere American Lieutenant escape, he was thrilled that it was happening to him. The following morning Maurice was driven in an Army truck ninty bumpy miles up the coast to a small French airdrome at Dong Hoi. He was to be flown from there some three hundred miles inland to a French Foreign Legion post at Xieng Khouang, a small city bordering the Plain de Jars in Laos. Upon arrival Maurice was escorted to an aged, two-seater, biplane known as a Potez-25, one of the few planes possessed by the French Army which had received no replacement aircraft or spare parts in over five years. As he climbed into the rear cockpit Maurice had serious reservations about this crate's ability to fly thirty miles, much less three hundred, but with the French controlling his movements, he had no choice. Pilot and passenger were buckled up and ready to go when a strange thing happened on the way to Xieng Khouang - the timeworn engine refused to start. Try as they might, nothing anyone did to it could produce more than an occasional metallic belch festooned with a few puffs of black smoke. After tinkering on the Potez-2S for a good half hour, the French threw in the towel and unhangered a small twin-engine Potez bomber which appeared to have been kept in first class condition. Of the two, this twin-engine plane, sporting a pilot and copilot, was much better suited for a three hundred mile flight over dangerous terrain, and Maurice wondered why it hadn't been selected in the first place. Then he realized that the French, terribly short of irreplaceable gasoline, had only been attempting to conserve what little they had left.

The flight to Xieng Khoyang was uneventful, and when the plane landed on the Plain de Jars Maurice was met by a Lieutenant in the French Intelligence who immediately took him to his quarters which they would share. Nearly four hundred Legionnaires, most of whom were German, and a handful! of French officers manned this remote post. As for Maurice, no one other than the post's commandant, a Major, and the Lieutenant would know his identity or raison dtre. The second night at Xieng Khouang, Maurice was invited to dinner with the Commandant who informed him that the nearest Japanese were almost two hundred miles away in North Vietnam, beyond the rugged mountains to the east. In fact the Japanese Army had practically ignored the existence his command confident no doubt that that it posed no threat to their operations. At that moment in time, however, such an assumption was correct, but conditions were about to change. Having been sequestered in quarters for four boring days, Maurice was elated to learn that five Free French Commando Units were to be air-dropped into strategic parts of Laos that very night, and one would land in their area. Initially their mission was to cache airdropped modern weapons and ammunition in places where French Army units could secretly rearm to attack the Japanese from within, if and when an Allied invasion of Indochina occurred. They were to operate clandestinely, and do nothing to alert the Japanese. Until the proper time came, they could fight only as a matter of last resort. After dark Maurice and the Lieutenant slipped away from the post to a clearing on the Plain de Jars where they marked the drop area with flares and lit them when radio contact with the plane, a B-24 bomber, indicated she was on her way in. The bomber flew and as low over the area, parachutes suddenly popped open as eleven commandos, in full battle gear, hit the silk. Maurice would never forget this thrill-packed moment when he stood in the eerie yellow light of flares, on a place called the Plain de Jars, in a strange land called Laos, thousands of miles away from family and friends, and surrounded by dangers that offered little promise for his safe return home. No, Maurice could never forget how his body tingled with excitement excitement enhanced by the knowledge that he was slated to join this elite group upon its arrival, and that time had come. Maurice joined the commando unit with the assigned rank of Lieutenant in the Free French Army. A Major Arroles was in command and under him were five Lieutenants and five Master Sergeants. What immediately impressed the newcomer about these eleven men was their superb physical condition and esprit de corps. They had been trained in North Africa by British and American Commandos, and survived their final test which consisted of being parachuted into several the wilds of India to live by their wits for months. Maurice characterized them as, "A real tough bunch". An old farmhouse several miles from the Post served as the Commandos' home away from home and base of operations. A radio promptly activated gave them direct contact with headquarters in India to permit coordinated action whenever arms and essential materials were to be air dropped, as well as information concerning Japanese troop movements brought to them by

friendly natives. Word that Maurice was alive, well, and an active member of their Unit was also passed to the American high command in India. For almost two months the commandos operated in this area. During that time B-24s, said to be flown by Canadians, dropped canisters packed with tommy guns, sten guns, carbines, ammunition, hand grenades, K-rations, a few small aircraft bombs, and other supplies of particular interest to fighting men. At first French Army trucks hauled this material away, over rutted dirt roads that snake through the mountains and tropical rain forests that abound in northern and eastern Laos, to French garrisons or cached it for ready use when the Allies invaded. It took the Japanese about six weeks to learn that something unusual was taking place at Kieng Khouang and to start sending troops into the mountains to block the few usable roads to the east. How many trucks were intercepted was not known, but when trucks suddenly ceased coming and natives told of enemy troops moving closer to their area, the Commandos called off further air-drops and began preparing for impending trouble. Since the initial air-dropping of supplies, the Commandos had been stashing a considerable amount of them in mountain caves for their own use. To accomplish this each man packed 30 to 40 pounds of gear over distances of up to 2S miles in a single night. At first, Maurice, who stood five feet tall and weighed but one hundred and fifty pounds, could not keep up with his superbly conditioned comrades, but he was a wiry, strong willed young man who, within a month's time,was able to hang in there with the best of them. When General de Gaulle entered Paris on August 26, 1944, signaling the defeat of the Vichy government under Marshal Petain and the liberation of France, the Japanese had paid little attention to the puny French military forces in Indochina, and placed no new restrictions on French civilians. By early March 194S, however, Japanese armies ~Y=~ had suffered calamitous defeats at the hands of the British in Burma, and by the Americans in the Philippines and Iwo Jima. In addition to that, with their once formidable navy gutted by American seapower, and their air forces unable to deter B-29 Superforts or carrier based aircraft from bombing the homeland, the situation had turned desperate. Then on March 9, 194S, coincident with the great Superfort raid on Tokyo wash which flattened sixteen square miles of the city and killed 100,000, the Japanese, fearing an American assault, captured all French military installations in Indochina and soon afterward interned French civilians. Such a move came as no surprise to Major Arrolles, For several weeks his commando force had been keep packed and ready to move out at the slightest hint of a Japanese takeover for he was well aware that tensions between the French and Japanese were mounting. When radio contact between his unit and French Army posts around the country was suddenly lost, the Major immediately moved his men back into the jungles. Two hours later the Japanese surprised the Legion Post, killing several men and capturing the remainder. Now playing by different rules, the five commando units were free to conduct guerrilla warfare against the Japanese. Maurice's unit, using several different hideouts deep in the mountains of eastern Laos, were quick to commence hit and run raids on Japanese targets.

Helping them as scouts, and-porters to carry heavy Loads from one hideout to another were tough little Meo tribesmen who hated the Japanese. The commandos never thought twice about traveling a hundred miles on foot to take an enemy target by surprise, and, since joining the unit, Maurice , who had become physically as tough as his comrades, readily participated in these raids. One of Maurice's most memorable mountain ambushes occurred in early May 1945, when Meo scouts reported a thirty truck convoy loaded with more than 200 troops and many supplies, working its way through the mountains towards Xieng Khouang. Anticipating the ambush of just such a target, the commandos had previously selected a ravine through which the convoy had to move. Its steep sides provided ideal protection for the attackers, and placed them a good forty feet above their prey. The commandos moved into position late that night and waited. Ten of the commandos, including Maurice, participated in this raid, and at dawn were spread out fifty yards apart along the rim of the ravine. Each man was armed with a IS kilo aircraft antipersonnel bomb (shipped too late to reach a French airdrome, but cached in the area for just such an occasion), a tommy gun, and several hand grenades. These aircraft bombs, in this instance the commandos' primary weapons, were armed by small propellers in the nose which spun as they fell from the plane and readied them to detonate on impact. Falling a mere forty feet over the side of a ravine, however, would not do the trick, so the unites armament specialist showed the others exactly how to spin the props by hand until they were armed and ready to explode. This hairy business was closer than Maurice ever wanted to get to a game of Russian Roulette. It was about noon when the truck convoy began slowly moving along the road below, and when the lead truck-came abreast of the last commando he opened fire with his tommy gun stopping it dead and halting the convoy on the single lane, dirt road. These shots also signaled Bombs Away'. Maurice, praying his armed bomb wouldn't hit a tree limb, heaved it over the edge of the ravine and immediately ducked back. In seconds raging hell broke out below. The lead truck lay on its side on-fire. Thick clouds of dust coupled with black smoke from burning vehicles saturated the area as mobs of Japanese troops, believing they were being bombed from the air, piled out of trucks to run amuck. To compound the pandemonium the commandos quickly heaved hand grenades down on the convoy, sprayed it with tommy gun fire and, before the Japanese knew what hit them, got the hell out of the area. There had been no time to accurately access damages but this certainly had been an important convoy and from the number of burning and damaged trucks they had been able to observe along with numerous Japanese casualties, the commandos concluded that their efforts, without a single casualty, had been highly productive. The commandos never remained inactive for long. Traveling from their hideouts mostly at night, they infuriated the Japanese with phantom like hit and run tactics as they shot up outposts, ambushed truck convoys, destroyed a few small but important bridges, and vanished. Their vital contact with headquarters in India was maintained by a radio operated off a 6-volt battery, kept charged by means of a small steam-driven generator. This ingenious device, their lone link to the outside world, remained operational for the duration, and permitted them to be resupplied .

About the 25th of May 1945, Meo scouts brought news of a sizable enemy convoy approaching a bridge the commandos had left standing because it had not been used to accommodate military traffic. Upheld by concrete piers, this steel-girder bridge crossed a steep ravine, bottomed out by a boulder studed river. A river that could be whipped by sudden torrential rains into a thundering, white-water monster. At this particular time, however, water beneath the bridge was a waist-deep pussy cat making demolition work feasible. The Mess also reported the convoy stopped for the night about five miles down the road from the bridge where a large contingent of Japanese troops was encamped. They then drew a rough map in the dirt to show the bridge guarded by two soldiers on either end of it, and a few yards downstream a light machine gun manned by two more soldiers. With the layout well in mind, the five commandos, two of whom were demolition experts, set out that evening to blow the bridge some thirty miles from their hideout. It was dark and moonless when, at about 2 A.M., the little band of commandos neared the bridge, and split up according to plan. Fading silently into the shadows, one man went to eliminate the two guards on the far side of the bridge, another to kill those stationed on the near approach, and Maurice, in charge of the group, moved off to silence the machine gun nest. The two demolition men, meanwhile, waited until the closest guards were knocked out before going under the bridge to plant their charges. Maurice, carrying a tommy gun loaded with 45 caliber bullets, crossed the river and gingerly worded his way towards the target. As he peered into the darkness for some sign-of the enemy, shots suddenly were heard in the vicinity of the bridge. At that same moment, Maurice found himself confronted by two Japanese soldiers sitting alongside their 25 caliber machine gun. The Japs fired first, followed a split second later by Maurice, and it was all over. Maurice had been shot in the right knee and foot, but the two men from Nippon had departed this earth. With a bullet hole completely through the joint of his left knee and another through the arch of his left foot, Maurice somehow managed to walk more than fifty yards to the bridge, climb the river's bank, and sit down. By this time the others, having knocked out their targets, were helping the demolition experts place explosives. Not wishing to disrupt the work, Maurice calmly explained that he'd been hit and couldn't join them. While he waited, Maurice examined his tommy gun and in so doing found embedded in the base of its ammunition clip a Japanese 25 caliber bullet. Having fired the gun from a waist high position, Maurice was quick to visualize that clip, about a foot long, hanging down in the vicinity of his private parts, and, with trepidation, realized how lucky he'd been. Had that bullet missed the clip by a mere half inch, he could have been knocked out of the ball game in more ways than one. The commandos, working swiftly in the dark, soon finished rigging the bridge to blow. All there was left to do was to light the fuses and get the hell out of the area before the Japanese caught up with them. When Maurice attempted to stand, his bum leg collapsed and he fell to the ground giving his comrade the first indication of how severely he was wounded. Gauze

compresses were immediately applied and bandaged in place. At the same time, bamboo cut with machetes was lashed together to make a jury-rigged litter upon which Maurice was hurriedly carried well away from the bridge while fuses were lit. With several blinding flashes accompanied by thunderous explosions, the rubble of what was once a bridge flew in many directions, and was left collapsed into the ravine. If the Japanese were not aware of trouble at the bridge site, they were now. Aware that tough little Japanese soldiers could soon be dogging their trail, the commandos headed back to their mountain hideout as fast as they could. To keep prying eyes from tracking their moves, the commandos generally traveled at night. In this instance, however, it was soon daylight, but fear of being pursued forced the little group to hurry on. Carrying the stretcher along rough jungle paths, and over steep hills was grueling work, but the Frenchmen struggled on for more than three hours until, physically exhausted, they literally dropped. Realizing the futility of attempting to carry Maurice further without help, one man then went on to the camp and brought back the others. They had been back in camp a little over two hours and Maurice, following a morphine shot and having had his wounds attended to , was resting comfortably when the shit hit the fan. Two very excited Men tribesman suddenly raced into the camp with the alarming news that hundreds of Japanese troops had started up the trail to attack the camp. The commandos activated their emergency evacuation plan at once. With precision and speed supplies were loaded on several small Mongolian ponies, crammed into back packs to be carried by the commandos and a few Meo porters, or stashed away in well disguised caches. Maurice was put astride one of the diminutive ponies, and the commandos moved out. The trip, of at least eighty miles of mountainous terrain and tropical rain forests, promised to be a very difficult one for Maurice. Although his fellow commandos sincerely doubted he could survive the march, they had no intention of abandoning him. They had traveled only a few miles, however, when the situation resolved itself. Maurice's scrawny mount, which had begun to weave from side to side, suddenly veered off the trail, staggered headlong into a tree, and expired with what sounded like a sigh of relief. Maurice was finally willing to admit that he was at the bitter end of his physical rope. The futility of his desperate but feeble efforts to keep up with the others had only slowed their progress, and seriously endangered their lives. As much as he detested quitting, Maurice told his fellow commandos to go on without him, and insisted there was no time for debate. To hide him from the approaching Japanese, Maurice was carried fifty yards back into the jungle and sat him down with his back against a giant tree. He had a canteen of water and emergency rations to sustain him until the Meo chief, guiding the party, returned to send help from his native village. Wishing him well, his friends reluctantly hurried off leaving Maurice with his carbine and .45 automatic to contemplate what he would do should the Japanese find him. They had been gone about ten minutes when one of the sergeants returned. With tears in his eyes, he told Maurice that no matter what happened he would remain with him. Then hoisting him to his back, he carried Maurice deeper into the jungle. About two hours Later, a horde of

Japanese troops could be heard double-timing it in pursuit of their friends. They passed without incident. The next day the sergeant made his way to the Meo village . whose chief was guiding the commandos over the mountains, and obtained help consisting of two men, and a horse somewhat larger that Maurice's previous ill fated mount. In all, it took Maurice three and a half days from the time he was Left in the jungle until he arrived at the Meo village. By that time the chief, Chong Hua by name, had returned. He was a short, chubby little man, dressed as though ready for bed in what looked like black cloth pajamas, whose appearance belied his inordinate physical stamina and strength. He told how the commandos had left the Japanese lost in the midst of a rain drenched jungle, and continued unhindered to their new mountain hideaway. Maurice was astounded to learn that the Meo village was no more than five miles from the former French Foreign Legion Post on the Plain de Jars which was now occupied by the Japanese, and he feared for the safety of the Meo tribe. Should the Japanese find out that a commando, one of their most hated enemies, was being harbored by them, they would vent, as usual, their barbaric frustrations by wantonly killing men, women, and children, and gutting their village. Chief Chong Kua, well aware of the danger the presence of Maurice posed for his people, was quick in moving him. Still traveling astride the horse, Maurice was taken some two miles through a trackless jungle until they came to a well concealed, steep-sided ravine. Here, close to a picturesque little waterfall, the Chief and his men built Maurice a sturdy, one room grass shack in a little over four hours. Maurice lived alone for the next six weeks, during which time the Meos brought him food twice daily consisting, for the most part, of corn mush, rice, bamboo shoots, and an occasional chicken. He changed the compresses on his wounds each day , and, lacking replacements, used the same ones over and over by soaking them in an antiseptic solution of acriflavine he made by dissolving the tablets in water. This was the only medication ever applied to his wounds and they healed without even a hint of infection. From the onset Maurice was fiercely determined to walk again and, as his wounds healed, he gradually began to exercise and to walk using a heavy stick for support. During his lonely, uneventful existence there was one particular day that Maurice will never forget. Standing ankle deep in the stream, preparing to take a bath, Maurice had a sudden gut feeling that someone was watching. Glancing towards the bank, he was stupefied to see a huge tiger, less than fifty feet away that had stopped and was staring at him. Although his carbine was leaning against a nearby boulder, Maurice knew better than attempt to make a dash for it. So, he and the tiger simply stood eyeballing each other for several seconds that to Maurice seemed to linger forever. With a low growl, as though clearing his throat, the big fellow broke off the eye contact, ambled down to the stream, took a long drink, then turned and majestically strode away. As Maurice's wounds healed and his strength returned so did his burning determination to rejoin the commandos, but it took six frustrating weeks before he could tolerate the pain of

walking. Then, with Chief Chong Kua guiding him, Maurice set out on foot for the commandos' new hide-out, some eighty miles away in the mountains to the north. It took him a little longer than it normally would to cover the distance, but Maurice was still going strong when he walked into camp. His arrival triggered a joyous celebration by fellow commandos none of whom had ever expected to see him again. Maurice soon learned that the Japanese, having suffered disastrous losses on all fronts, were now surrounded in their homeland vowing that it would be defended to the death by every man, woman, and child. Furthermore, the Japanese threatened that if such an invasion took place, all prisoners of war would be put to death. Headquarters in India had also reported the disheartening news that the four other commando units parachuted into Laos had either been captured or killed by the Japanese, and ordered Major Arroles to cease all guerrilla activities, to keep a low profile, and to report pertinent information. Planning and executing a tremendous military operation, such as the invasion of Japan would entail, could take many months. Maurice knew this and pondered the prospect of simply hanging out in the mountains with nothing more important to do than play hide and seek with the enemy, and decided lathe hell with it" - he would bail out, and head for Allied lines. Maurice informed headquarters of his impending departure, and was told that the nearest Allied facility to him was a small U.S. Army weather station at Size Mao, China. On a beeline this remote station, maintained to assist pilots flying the Hump, was about 27S miles away. Maurice, not being akin to a bee, with no compass and only rough map to guide him, would have to "by guess and by God" his way. This, he understood, meant walking a much more circuitous route over roughly defined trails that zig-zagged back and forth over mountainous terrain or wound, sometimes aimlessly, through sultry jungles, which amounted to approximately 500 miles. In this archaic part of the world, There cars and trucks were nonexistent, Maurice would only twice find a road connecting one village to another, and these were simply rutted dirt ones along which people either walked or moved goods in ancient horse drawn carts. That incalculable obstacles, such as the possibility of encountering Japanese troops or bandits, his inability to speak Chinese and only pidgin Thai (the language of Laos), failed to diminish Maurice's unswerving confidence in his ability to attain his objective - escape to America. Furthermore, the well intended efforts of his comrades in arms to persuade him not to attempt such a perilous journey served only to hasten his efforts to get underway. Just after sunrise on July 25, 1945, Maurice bid good-by to his commando friends. Having shared the fortunes of war together these rugged men, wishing each other heartfelt Godspeed, adequately conveyed their suppressed inner emotions with direct eye contact, and the strength of a prolonged handshake. That done, Maurice headed out, and never looked back. Instead of walking a direct line north across the Plaine des Jarres, the presence of Japanese troops there forced Maurice to take a more circuitous mountain route well to the east of it. Because there were hundreds of miles ahead of him, and he was obsessed with the desire

to reach Tze Mao as soon as possible by covering at least twenty miles a day, Maurice elected to travel in an amazingly austere fashion. In so doing he eliminated anything that might slow him down, or that he could conceivably do without. He was dressed in khaki shirt and trousers, jungle boots made of canvas with rubber soles, and a commandos black beret. He carried no canteen as this being the rainy season, water enroute would be plentiful. In his lightweight back-pack were a few essentials, such as some extra rounds for his 30 caliber carbine, a small first aid kit, emergency rations in the form of two cups of uncooked rice, an extra pair of vex, and a change of underwear. On his belt hung a razor sharp hunting knife. Incredible as it seems, Maurice carried no ground sheet or poncho, because as a commando he was used to traveling in weather fair or foul, and rain, at this point in time, was the least of his worries. Besides, he calculated that with villages throughout the region seldom more than twenty miles apart he could always obtain food and lodging in a native's hut for a small amount of money. If not, he was not adverse to curling up on the ground for forty winks or more. As for money, Maurice was in good shape. His money belt contained small silver coins small silver bars, some paper money which most Laotians scorned, and half dollar sized pieces of silver commonly used in the opium trade. These large coins came in especially handy for much of his journey was through the opium country of Laos. The paucity of roads and human trails cut through the mountains and jungles of northern Laos oftentimes forced Maurice to follow game trails reverently hoping they led in the right direction. On several occasions he hiked considerable distances along game trails only to discover he'd gone astray, and had to backtrack. Seldom, during his lonely travels did he meet others who -might give him directions. It was only in the villages where a small piece of silver would sometimes hire a reluctant guide to the next village or, failing that, directions drawn in the dirt accompanied by the vigorous pointing of fingers would head him in the supposed right direction. Maurice generally found the natives friendly. For a small piece of silver, he seldom had difficulty obtaining a place on the dirt floor of a hut to spend the night, and a Share of the family's food. Food, such as it was, consisted mainly of rice, sometimes bamboo shoots and, on rare occasions a Thinly portioned out chicken. Only twice in his month long journey was Maurice forced by darkness to lie down in the middle of nowhere and rest for the night. Maurice, who preferred to travel inconspicuously on foot rather than ride horseback and have to care for the animal to boot, did at one point consent to ride a horse. He'd hired some natives to guide him to the next village which they indicated was some twenty miles away over a very steep mountain trail. Then, because it would be in his best interests, they insisted in taking him there on horseback. This, of course, would cost an additional amount of silver. Knowing he was being conned, Maurice, in no position to argue with these tough tribesmen, agreed and paid the price. The first time the horse, which was not a very large animal, and Maurice met eyeball to

eyeball, the beast laid back its ears, sneeringly curled its upper lip to flaunt a mouthful of yellow teeth, and vigorously shook its head as though to say, "Oh, no - not this. Unfazed, Maurice quickly mounted the beast who, to the undisguised delight of the villagers, immediately bucked him off. Chagrined but undaunted, Maurice climbed back on the nag. This time, however, he was ready when the bucking started and remained on board until the animal decided to stop. With that, the small group moved out. Because the natives could ride the horse with no problem, Maurice figured that he probably smelled different, but whatever the reason it was no secret that the four legged beast just plain didn't like him. On the tight mountain trails whenever the horse started to buck, Maurice would jump off. He would then get back on and the thing would plod steadily on until, without obvious reason, it would start bucking again. While traveling along one section of very narrow trail, on one side of which was a sheer drop off several thousand feet, the horse started bucking and acting plumb loco. Whereupon Maurice immediately concluded that he'd be a hell of a lot better off walking, and quickly dismounted. A few eye-blinks later, the distraught animal plunged over the mountain side to its death. Nearing Ben Qua, a town about twelve miles east of the Chinese boarder, Maurice almost wandered into a garrison of Japanese troops. Just before bashing his head against this hornet's nest, however, he was warned by natives. Immediately thereafter an outpost sentry spotted him and sounded the alarm. With that, Maurice, as military pilots used to say, "Firewalled the go-handle", and took off like a tattooed ape. Spurred on by the shouts of enemy troops assembling for the chase, Maurice sped along the banks of a small river. For five or six miles he ran as fast as his legs would go with the enemy hot on his tail. As he ran, his badly worn jungle boots picked up sand which rubbed his feet bloody raw, but he couldn't stop to tend them. To do so meant capture or death. Maurice finally eluded the Japs by fording the chest deep river and taking refuge in a dense forest. When certain the area was clear of enemy troops, Maurice, driven by his unyielding determination to reach Tee Mao and his mind immune to the pain engendered by his bloodied feet, finally made his way into China. The first village he came to the natives were somewhat less than friendly, for they were deathly afraid of the Japanese who, without compunction, would lop off heads just for the hell of it. But Maurice could go no further, his feet just plain gave out, and he was forced to remain there. Although the Chinese shied away from him, a bit of silver bought him some cooked rice and a night's lodging in an abandoned shack. He spent a restless night fearing that the villagers, to ingratiate themselves , with the Japanese, would rat on him. Taking no chances that the Japanese, told of his presence, might be enroute to get him, Maurice was up and away with the first glimmer of dawn. It suited him fine to think that should troops arrive only to learn he'd escaped them again the informant's head would probably roll. From this point forward Maurice was destined to walk barefoot for he'd discarded his completely worn out jungle boots. The soles of his feet, however, were as tough as shoe leather, a result of having hiked hundreds of miles as a commando, and oftentimes having gone barefoot to save his boots. It was the tops and sides of his feet where the skin had been rubbed raw that gave him considerable pain. Nevertheless, Maurice ignored the pain as best he could, and never

slowed his normal pace. A few days later Maurice arrived at a large Chinese town, remotely nestled high in the mountains of southern Yunnan Province. Here, in spite of his matted beard, unkempt hair, and clothing tattered beyond recognition, when it was learned he was an American, Maurice was immediately ushered to the home of a school teacher who spoke a smattering of English. From there he was taken to the Mayor's house where he found himself the guest of honor at a hastily prepared banquet. Present besides the Mayor and the school teacher were three other dignitaries; the ranking military officer in town, one whom Maurice thought to be some kind of a Commissar, and one type he never could figure out. At any rate it was a festive occasion for all hands as none or the Chinese had ever seen an American before and the famished Maurice was delighted to be the guest of honor at a Chinese banquet, anybodys banquet for that matter. The participants had no sooner taken their places on stools around a circular table than jiggers before them were filled with a colorless liquid similar to the potent rice wine sari. As protocol would have it, the person sitting to Maurice's left raised his jigger and drank a toast to him which Maurice was obliged to return. Then Maurice's jigger was refilled and the next man to his left raised his, and again Maurice responded in kind. So it went with the three remaining VIPs drinking to Maurice , and he in turn belting down one to each of them. Maurice was beginning to think he'd been bushwhacked, but was saved when the drinking stopped with the appearance of food. A large communal bowl heaped high with boiled rice was placed in the center of the table for the banqueteers, armed with chop sticks, to attack at will. The main dishes of roast pork and chicken were also placed on the table within reach of everyone to be eaten out of hand. Beef was scarce in these mountains because there was no refrigeration, and even a pig when killed had to be cooked and eaten without undue delay. Maurice, who set about devouring the food like it was going out of style, was quick to learn that bones were disposed of by simply tossing them over one's shoulder to the floor. The final tidbit of etiquette to which he was introduced concerned the extent to which a guest enjoyed his meal, and this was flashed to the host by a resounding belch. Not wishing to appear uncivilized, Maurice out-belched all others. The next day Maurice purchased some black cotton cloth, borrowed scissors, needle and thread and made himself a new set of duds in the form of black pajama-like rigs the natives were sporting. Now all he had left of his original clothing was his commando beret and one set of ragged underwear. For the next one hundred miles or so Maurice would go shoeless as the Chinese wore only clogs or grass slippers around town, and shoes were not yet in vogue. Besides, even if he had shoes, the pathetic condition of his feet would not accommodate them. Nevertheless, he had no intention of letting feet delay his journey He would doctor them with what little medication he had until it was gone. After that, there was nothing he could do but keep going. As the seldom used trails leading to the next village wandered more than twenty miles through rough mountainous terrain and often became so obscured as to cause strangers

considerable grief, the Mayor provided Maurice with a guide. This unexpected parting gesture of friendship proved to be a most helpful one. Just after dark on 24 August 1945, a thoroughly exhausted Maurice Hughett reached the entrance to the U.S. Army Weather Station at Size Mao, China. To reach this American sanctuary where his most treasured dreams would begin to come true, he had traveled more than 500 awesome miles in 30 days. Desperate to get there he had driven his aching bones on that last day to the outer limits of their physical capacity. In so doing he had walked further than he had ever done in one day - assistance calculated to be about 35 miles. As far as Maurice's appearance was concerned, it was some-+ thing less than atrocious. With Iris black commando beret jauntily couched upon a nest of matted hair - much of which hung down on all sides of it, his deeply tanned face with a scraggly beard obscuring its best features, his jury-rigged black pajamas, a carbine slung over his shoulder, and with bare feet covered with bloody, ulcerous soars, Maurice was indeed a pathetic picture of a man. As he neared the gate his entire body commenced to shake with joyous excitement spawned of great anticipation of things to come. When a Chinese soldier guarding the weather station's entrance spotted this weird apparition coming towards him, he, in no uncertain terms, shouted, "HALTS.- To back up his authority this guard carried a rifle with bayonet affixed which he handled as though he'd just as soon use it as not. Being a prudent man, Maurice immediately anchored both feet to the ground and cried out that he was an American. Having no means of identifying himself, or to help belie his God-awful appearance, Maurice had one hell of a frustrating time trying to convince the Chinese, who spoke no English, that he was an American. For all the guard cared, Maurice, with his commando beret, was a Frenchman, and kept insisting he go away. Finally, one of the American soldiers, hearing the commotion at the gate, came to see what it was all about. Understandably, the soldier was shocked at Maurice's appearance which was unlike anything he had ever seen, but was soon convinced that if nothing else, Maurice was at least an American and brought him into the station. At the weather station Maurice was stunned to learn the war just was over - Japan having surrendered just ten days before he arrived. As he reveled in this glorious news, Maurice had no regrets about making his long trek on the premise that the war might be a more protracted one. But that arduous effort had cost him dearly. The six-footer was down to 125 pounds from 160, and his feet were so badly infected and swollen that he would be unable to wear shoes for some time to come. On top of that, he was suffering from the recurring chills and fevers of malaria which hit him the last day of his journey, but which Maurice, in his indomitable way, refused to Let stay his progress. Now after three and a half years of dreaming about it, he was once again with free Americans, and to Maurice that was all that mattered. In response to a query via radio, suggested by Maurice, headquarters in India confirmed that he was indeed a former fighter pilot from Bataan whose whereabouts had been monitored for some time. Having lost track of his activities for the past month, headquarters personnel were

glad to learn he was alive, and promised to send a plane for him as soon as possible. From that moment on Maurice became the uncomplaining recipient of VIP treatment. Following a hot bath, quinine for his malaria, medication for his feet, a change into fresh new clothing, and a hearty army style meal, Maurice hit the sack to sleep like a babe for the next twenty hours. He awoke to find that the weather station was little more than a two-story, wooden farmhouse with several nondescript out buildings. It was situated near what looked like a large cow pasture, but was in fact a grass landing strip. Believing he was headed for a speedy aerial departure from Tee Mao, Maurice's spirits went into a sudden flat-spin when he learned that because of the rainy season no planes had been able to land on the sodden strip for almost three months. During that time been the station had been resupplied by airdrops staged from a large American air base at Runming, China, some 250 miles to the northeast. To further batter his spirits, the rainy season was projected to last for at least three more weeks, and, until then, the field would not be considered safe enough to accommodate aircraft. Maurice could not abide being trapped in Tze Mao until the rainy season, in its own time, chose to go away, and refused to believe that a C-47 aircraft could not land on that field. As this was the bitter end of the rainy season with no recent downpours having been recorded, Maurice decided to check out the field for himself. He carefully inspected the entire area and was convinced that a C-47 cargo plane could safely land and take off provided only the north side of the field was used, but anything past the median line would court trouble in soggy ground. This information was radioed to the U.S. air base at Kunming along with an assessment of Maurice's physical condition which was considered serious and the treatment required beyond the medical expertise of weather station personnel. Kunming radioed back that if the weather held for the next two days a twin-engine C=47 cargo plane would be sent with supplies for the station, and to pick up Maurice. Accordingly, two days ' later two C-47 aircraft appeared over the weather station where the pilots were cautioned to land only on the north side of the field. The first plane landed and at the end of its run commenced a slow turn but hit a soft spot, and became stuck up to the wheel hubs in mud. Then the second pilot, having seen the first plane land safely but unaware of its problems, landed his plane. Near the end of the roll out he gingerly touched the breaks which inadvertently put the plane into an uncontrollable skid trait didn't stop until its right wing slammed into the side of the other plane. Now both aircraft were hors de combat, and Maurice, who was more than ready to depart Tze Mao forever, wondered if maybe he was just a little Snake-bit . The next day another C-47 arrived from Kunming, but this pilot wisely made no attempt to join his grounded compatriots. Instead, he parachuted five gallon cans of gasoline to refuel a small L-S - a two seater observation plane - that had accompanied him to pick up Maurice. The L-S, which had no problems with the grass field, could not make the round trip on one load of gasoline, When the ship was refueled, Maurice hurriedly climbed into the rear cockpit, buckled up, and the pilot took off. Although his head throbbed with the fever of malaria, the thrill of once