Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Sustainability Without Borders

Uploaded by

John SchertowOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Sustainability Without Borders

Uploaded by

John SchertowCopyright:

Available Formats

Original Posting: http://pagina20.uol.com.br/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=21557&Itemid=37 (Translation by M.A.

Kidd - Links have been inserted into the original article for background on IIRSA, Yoreka tame and photographs of this Ashananika school project)

Sustainability without Borders

By *Malu Ochoa April 24, 2011 Regional Integration to protect the Indigenous Peoples and to Conserve Biodi versity on the Frontier of Acre/Brazil Ucayali/Peru The border region of Acre (Brazil ) and Ucayali (Peru) is one of the areas formed by Indigenous Lands (Terras Indigenas), Units of Conservation, Native Communities and Reserve Lands (Terras Reservadas), wh ere indigenous and traditional populations live. In Acre the Indigenous Lands and Units of Conservation form a large mosaic with approximately 4,280,197 hectares or 30% of the length of the state. It is here that, in recent years, innovative social and so cioenvironmental sustainability have been developed by indigenous peoples, communities of the extractive reserves, riparian (traditional river peoples) and their representative organizations. These actors have been organized for recognition and monitoring of their collective territories and for sustainable use and conservation of their forests. But on both sides of the border there are threats to the integrity of these territories and to the ways of life of the indigenous peoples and traditional populations, including the peoples in voluntary isolation. These threats that are being leveraged by major infrastructure projects set the agenda of governments of the two countries that seek economic development and regional integration, such as roads and prospec ting for oil and gas drilling, and illicit and illegal activities, such as clandestine exploitation of timber, predatory extraction of minerals and drug trafficking. In Peru, as of 2000, the new Forest Law [Lei Florestal] and Wildlife [Fauna Silvestre] (Law 2738) permitted the creation of the "Bosques de produccion permanent", domain areas of the State dedicated exclusively to forest management. Within these, are defined Units of Exploitation, large areas of forest for the removal of wood, by contract bidding, were delivered to businesses and legal entities/persons in the form of 40 year concessions. According to the Instituto Del Bien Comum - IBC, there are concessions that amount to 50,000 hectares. It so happens however, that this legality contributes largely to the illegal logging in the region, becoming a true chaos for the indigenous populations. The great problem with this "shredding/retailing" of the Peruvian Amazon in the form of forest concessions was generated by the common practice of governments of the Amazon countries, to create policies for the region with purely economic goals. The intention is to remove the non-renewable natural resources and to construct large scale infrastructure projects (IIRSA), without considering the negative impacts and, worse, without knowing the local demands and/or realities. In the Peruvian case, without the "knowledge" of the existence of native communities and of populations of isolated indigenous peoples. It is out of the socio-environmental impacts that are already occurring, with the start of some of the construction and fruition of their intent, that serious conflicts begin to take shape in the Acre/Ucayali border strip. One of the

most shocking is when these invasions cross the border in this frontier region, forging into Brazilian territory, more specifically in the official Terra Indigena Kampa (Indigenous Territory of Kampa) of the Amnea River and the Serra do Divisor National Park, and occasions the illegal extraction of timber. Equally or even more shocking than the illegal extraction of timber is the legalized predatory extraction, and this, with forest certification. This applies to the case of the logging company Forestal Venao S.R.L. created in 1996 to work in the Ucayali region. It began its work with five indigenous communities : Sawawo Hito 40, Nueva Sahuayo, Santa Rosa, Nueva Victoria and El Dorado, supported the titling of these territories in exchange for the removal of timber and used the labor available in the community. Sawawo Hito 40 was the first [village] to work in the logging, in 2005, initiating the process of certification by the SmartWood / Rainforest Alliance, and in less than two years, the community of Sawawo found itself in serious difficulty. One example of how companies with interests that are exclusively economic assume the role of the Peruvian State that facilitates the procedures without monitoring the impacts caused in the region. Articulation and exchange: political strategies of the indigenous peoples and traditional populations The Comisso Pr-ndio do Acre (Pro-Indian Commission of Acre), by means of its most recent program of Public Policies and Regional Articulation, has been working, in recent years, for the strengthening of the policies of protection for the isolated indigenous peoples, for indigenous peoples and movements for the protection and conservation of biodiversity of the Acre-Ucayali border and for their qualified participation in public spa ces. Also, the strengthening of the network of articulation between the organizations of indigenous and traditional peoples for exchange of information and, with this, for subsidiary strategies and actions that in conjunction influence in public policy, are the focuses of this work. We organize, produce and make public, documents with information and data about the border between Brazil and Peru that in addition to visibility, show the area of institutional activity. The gatherings and meetings that take are held with representatives of social movements in Brazil and Peru, by means of the Trans-Border Working Group (GTT- Grupo de Trabalho Transfronteirio), since 2005, have contributed to the exchange and update of information about public policies, negotiations on the Peruvian and Brazilian government infrastructure projects and about legal and illegal economic activities taking place in the border region. Also, we have provided information from the reports from local communities about the negative impacts of these processes. Because of my participation in the Seminar on Research Experiences, Records and Cultural Management by the Indigenous and Traditional Community of Alto Juru, held in the Yorenka tame Center in the municipality of Marechal Thaumaturgo, on March 29 and 31, I heard important project experiences, records and research on the knowledge that the populations of Juru have in relation to the use and management of natural resources. Experiences and knowledge that, at the same time, guarantee their survival and provide important environmental services to humanity. The Seminar, which reunited rubber tappers and indigenous peoples, was, like so many other meetings, an important and efficient exchange of ideas and dreams: establishment of partnerships for collective consideration, reaffirmation of the importance of the relationship with the environment by those who live in the forest, of their spiritual and economic way of life, and ongoing work that enhances the forest with a view toward sustenance and permanence for future generations. In this meeting, once again meeting my friend Edwin Chota, Ashaninka leader of the Saweto community of Alto Tamaya, a tributary of the Ucayali River, able always to visit the Apiwtxa community, which according to him is a

way to achieve internal strength. Who from the Peruvian side of the border, has been in my view, a symbol of resistance against an entire economic policy of timber extraction, in solitary form, has been gradually expanding its network of allies for the titling of their land. There have also been conversations with Isaac and Benk Piyanko, Ashaninka leaders who play an important role in the joint defense of a social and environmental policy for the region. The Ashaninka of the Amnea, since 2004, have been utilizing various strategies to protect their territory. It was they who, experiencing the direct impacts from invasions by loggers in various parts of their Land, called the world's attention to the border problems. In a conversation we had during the Seminar Edwin, Isaac and Benk recounted their views for me on the events on the Acre and Ucayali border. I am pleased to present some of these. Edwin Chota: The community of Saweto represents a history we have been studying since 2002, when we began to organize against the timber exploitation. In that year, when we organized in light of the Forestry Law (Lei Florestal), which granted concessions in nearly the entire Amazon forest of Peru, we initiated coordination at the regional level in the province of Coronel Portillo. Prior to this, there was no knowledge that there were Ashaninka in the Tamaya region, we were dismayed when we filed application for recognition, our very existence being in doubt. After many questions from the police about who I am, where I came from, what I do, we came to understand that, behind this, politically, we were coming face-to-face with an activity of the State. Only after great insistence did we have the first meeting with representatives of the Ministry of Agriculture. Since then, we initiated the articulation/coordination and we started to work with the government. At this point we had the recognition and began to denounce the illegal and indiscriminate splintering of timber stands in our region. It was a total disaster, there was plundering of cedar and mahogany. We began to denounce this with ever more people arriving, the authorities did not believe them. Only after many denunciations, the Defensoria del Pueblo (Office of the Public Defender), installed its office in the city of Pucallpa. It was then that we saw a light. Although the National Institute of Natural Resources (INRENA) say that they could not do anything because the whole region had been granted concessions, the Public Defender spoke of our right to land. But it was only in 2005 that the resolution came to recognize the Alto Tamaya. With regard to the title, we had no further response. Saweto has been recognized since 2003, but we are among the 180 communities in the Amazon that still require [land] titles. We initiated this struggle with 36 families and, at present, we are 20 families enduring the entire negative force of the timber interests against us. Many communities have been illuded and convinced to leave their homes to work for them. Unfortunately, a bar of soap, a cartridge and salt and deceive the families and, as there are no alternatives, people accept the job, take their children and leave their homes. These families are found scattered throughout the Tamaya river basin. Their community organizations are very fragile; the majority of leaders are in favor of the loggers. It is unfortunate but we are not able to prevent it without presenting another alternative. Therefore we are seeking support, to capacitate our raising the awareness of our people and to continue to confront the indiscriminate removal of timber in our region.

It was at the beginning of the binational coordination of Peru and Brazil that we approached from Apiwtxa and, in the meetings of the Grupo de Trabalho Transfronteirio, all these questions were discussed. It was from there that recommendations went to governments as did the demands of the indigenous peoples. I would hope, from these, that continuity be given to the work we started and that they respect our ideas. We need to understand what the knowledge is that governments have about indigenous peoples, especially those living on the border. It would appear that our work is not valued, nor is the thinking of the people who, from within their culture are able to conceive of alternatives that are not just a timber economy. We are strengthening to resist timber labor, it is for this reason we here in Apiwtxa and in Yoreka tame, because it gives us strength to see their experiences. We seek a solution for our territory, our culture is in danger, seeing the children today, not finding a better future for themselves, this is why we want to establish a plan for living. This plan does not yet exist in the minds of my relatives. But, if there exists any project that we facilitate as much as we see from the Brazilian side, if there is an institution exerting the effort and desire to help us find a way out, we will not disappear with time, our struggle is to prevent the destruction of our forest. Isaac Pianka: The experience of working with forest management from within a village, does not fit. In the case of Sawawo, the company had promised to provide assistance to the community and did not do so. It stayed within the indigenous land, with a management plan developed for it and used the community. An indigenous community has a totally different conception of the world and this way of seeing the world was thrown off for a million errors. This left a deep impact on Sawawo, on both the forest and on the people. We noticed the difference when we, as cousins, brothers, of the same people, were received like strangers. We realized they were being manipulated. When Sawawo began the work, the company soon planned another community for continuing the timber exploitation across the Amnea river. The families of Sawawo tried to live, but the company realized it would be problem because of our interference. Then, it brought in Ashaninka from other regions of Peru and created another Native Community, which is "Shawaya." The green seal, because of Sawawo, can become a lie. People who buy their product do not know that it is killing a population that possesses important knowledge for humanity. This does not deal with just a mahogany tree. The cultural destructuring of a people is the end of a millennial knowledge; no price can be placed on this . Benk Ashaninka: The families have created a great dependency with the company. Now that it has left, they have become disoriented, thinking that you can only survive with the illusion of the outside world. Abandoning their territory, they will follow the company or go to the municipality. Seven families have migrated to our community and are under the impression that they will not survive in their own region. But, they are wrong, I observed that nature has been able to recuperate and, despite not having any more cedar and mahogany, there is still great wealth in Sawawo. In 2010, Forestal Venao left the region to avoid discredit to its image. But Edwin reports that the company is returning to the Alto Juru, right next to the Ashaninka/Kaxinaw Indigenous Land of the Breu River, at the request of some communities. In fact, it is more a marketing strategy and someone viewing from a distance may think this a matter of a "community demand."

As to governmental actions, there is a great contradiction. While governments participate in the great global debates related to climate change, global warming, etc.., the economic policies adopted by Latin American states in the Amazon completely disregard the rich biodiversity and the participation of local populations in implementing their enterprises for economic development. To incorporate some of the spirit of indigenous peoples and of the traditional populations helps us, non-indians, to change our way of understanding the development in the diverse points of view and interests, from whom and for whom. In times of so many natural disasters such as floods, droughts, storms, c aused by the impacts of the indiscriminate use of natural resources , it would be salutary to build a positive relationship with the forest. *Executive Coordinator of the CPI/AC

You might also like

- Two Spirit Names Across Turtle IslandDocument5 pagesTwo Spirit Names Across Turtle IslandJohn SchertowNo ratings yet

- Sacred Sites Draft ReportDocument98 pagesSacred Sites Draft ReportJohn SchertowNo ratings yet

- Indigenous Struggles 2012: Dispatches From The Fourth WorldDocument44 pagesIndigenous Struggles 2012: Dispatches From The Fourth WorldJohn SchertowNo ratings yet

- Indigenous Struggles 2013Document62 pagesIndigenous Struggles 2013John SchertowNo ratings yet

- Naso Outline For Intercontinental CryDocument2 pagesNaso Outline For Intercontinental CryJohn SchertowNo ratings yet

- 2009 The Bhopal of West AfricaDocument3 pages2009 The Bhopal of West AfricaJohn SchertowNo ratings yet

- 2009 16 Months and Counting - Australias Racist Intervention ContinuesDocument6 pages2009 16 Months and Counting - Australias Racist Intervention ContinuesJohn SchertowNo ratings yet

- 2010 So, Canada Endorsed The UN Declaration of Indigenous RightsDocument4 pages2010 So, Canada Endorsed The UN Declaration of Indigenous RightsJohn SchertowNo ratings yet

- 2010 Indigenous People, Diabetes and The Burden of PollutionDocument6 pages2010 Indigenous People, Diabetes and The Burden of PollutionJohn SchertowNo ratings yet

- 2008 Sacrificing The MekongDocument5 pages2008 Sacrificing The MekongJohn SchertowNo ratings yet

- First Nations Strategic Bulletin - Jan-May 2011Document24 pagesFirst Nations Strategic Bulletin - Jan-May 2011John Schertow100% (1)

- Proceedings Report of Contaminants and Environmental HealthDocument57 pagesProceedings Report of Contaminants and Environmental HealthJohn SchertowNo ratings yet

- Karaban Rally UpdateDocument5 pagesKaraban Rally UpdateJohn SchertowNo ratings yet

- Karaban Rally UpdateDocument5 pagesKaraban Rally UpdateJohn SchertowNo ratings yet

- 2008 Australian-Style Intervention of Indigenous Communities Moves To BrazilDocument6 pages2008 Australian-Style Intervention of Indigenous Communities Moves To BrazilJohn SchertowNo ratings yet

- X International Festival of Indigenous Film and VideoDocument5 pagesX International Festival of Indigenous Film and VideoJohn SchertowNo ratings yet

- Petition From The Porgera SML Landowners AssociationDocument3 pagesPetition From The Porgera SML Landowners AssociationJohn SchertowNo ratings yet

- From Money To Metals: The Good Campaigners' Guide To Questionable Funder$Document151 pagesFrom Money To Metals: The Good Campaigners' Guide To Questionable Funder$John SchertowNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Whole Grains: Training For School Food Service StaffDocument20 pagesWhole Grains: Training For School Food Service StaffSafdar HussainNo ratings yet

- An Economic Analysis of The Great DepressionDocument46 pagesAn Economic Analysis of The Great DepressionChetanya Choudhary100% (1)

- Trade-Offs - Between - Economic - Environmental - and - SociDocument17 pagesTrade-Offs - Between - Economic - Environmental - and - SociHshanCheNo ratings yet

- Anchaviyo ResortDocument21 pagesAnchaviyo ResortShafaq SulmazNo ratings yet

- Project COC v2Document13 pagesProject COC v2Louie RamosNo ratings yet

- Epc700 Paper 3 Reading (CP & QP)Document20 pagesEpc700 Paper 3 Reading (CP & QP)Sahid MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Good Samaritan Bob Kinney ArticleDocument10 pagesGood Samaritan Bob Kinney ArticleSilvio MattacchioneNo ratings yet

- CH 3 RULING THE COUNTRYSIDEDocument3 pagesCH 3 RULING THE COUNTRYSIDEKaushal NagarNo ratings yet

- LO1. Harvest Horticultural/ Crop Produce: The Learner Independently Harvest Matured Crops and Markets Them ProperlyDocument6 pagesLO1. Harvest Horticultural/ Crop Produce: The Learner Independently Harvest Matured Crops and Markets Them ProperlyJaideHizoleSapul100% (1)

- Kindfood MenuDocument2 pagesKindfood MenuVegan FutureNo ratings yet

- Job Description - Saaransh Agro Solutions - A Group of CompaniesDocument6 pagesJob Description - Saaransh Agro Solutions - A Group of CompaniesPawan KumarNo ratings yet

- TLE G6 Q1 Module 2Document17 pagesTLE G6 Q1 Module 2Charisma Ursua HonradoNo ratings yet

- Northborough, CambridgeshireDocument40 pagesNorthborough, CambridgeshireWessex ArchaeologyNo ratings yet

- All DocumentsDocument9 pagesAll DocumentsVineetha Chowdary GudeNo ratings yet

- Chapter-1: Organization Study at KERAFEDDocument78 pagesChapter-1: Organization Study at KERAFEDPrasanth SaiNo ratings yet

- Pangdan PDFDocument242 pagesPangdan PDFSphinx Rainx100% (2)

- The Potential For Cropping Index 200 at Swamp Area in Pelabuhan Dalam Village Pemulutan Subdistrict Ogan Ilir RegencyDocument28 pagesThe Potential For Cropping Index 200 at Swamp Area in Pelabuhan Dalam Village Pemulutan Subdistrict Ogan Ilir RegencyFarhanNo ratings yet

- CBLM PREPARE VEGETABLE DISHESDocument89 pagesCBLM PREPARE VEGETABLE DISHESGlenn Fortades Salandanan100% (11)

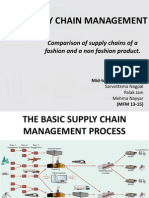

- Supply Chain ManagementDocument17 pagesSupply Chain ManagementsarvottemaNo ratings yet

- Weather Based Crop Insurance Scheme Kharif 2019Document62 pagesWeather Based Crop Insurance Scheme Kharif 2019Balan DNo ratings yet

- Land LawsDocument202 pagesLand LawsmahabaleshNo ratings yet

- 100 HPH Juice Recipes Nov13Document124 pages100 HPH Juice Recipes Nov13Picincu Irina Georgiana100% (5)

- What Are Tourism ImpactsDocument6 pagesWhat Are Tourism ImpactsJudi CruzNo ratings yet

- Survey and Availability of Some Piscicidal Plants Used by Fishermen in Adamawa State, NigeriaDocument4 pagesSurvey and Availability of Some Piscicidal Plants Used by Fishermen in Adamawa State, NigeriaInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)No ratings yet

- A 1369 e 00Document71 pagesA 1369 e 00Waseem A. AlkhateebNo ratings yet

- Partial Budget: A Partial Budget Is A Tool To Analyze Farm Business ChangesDocument8 pagesPartial Budget: A Partial Budget Is A Tool To Analyze Farm Business ChangesGeros dienosNo ratings yet

- Superior Types of Grass Used For Animal FeedDocument2 pagesSuperior Types of Grass Used For Animal FeedNaurah Atika DinaNo ratings yet

- 1877716-W.S No 9. Class VI - Kingdoms, Kings and An Early Rebulic (Hist) Sreeja.VDocument3 pages1877716-W.S No 9. Class VI - Kingdoms, Kings and An Early Rebulic (Hist) Sreeja.VsrirammastertheblasterNo ratings yet

- Ariyalur - RAWEDocument26 pagesAriyalur - RAWESunny Khan0% (1)

- Vegetable Planting Guide - Growing GuidesDocument4 pagesVegetable Planting Guide - Growing GuidesSheilaElizabethRocheNo ratings yet