Professional Documents

Culture Documents

HPS-A NZ Perspective by P Cushman

Uploaded by

Caitlin RossOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

HPS-A NZ Perspective by P Cushman

Uploaded by

Caitlin RossCopyright:

Available Formats

This article was downloaded by: [University of Canterbury Library] On: 29 August 2010 Access details: Access Details:

[subscription number 917001820] Publisher Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 3741 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Pastoral Care in Education

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t789751077

Health promoting schools: a New Zealand perspective

Penni Cushmana a University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand

To cite this Article Cushman, Penni(2008) 'Health promoting schools: a New Zealand perspective', Pastoral Care in

Education, 26: 4, 231 241 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/02643940802472163 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02643940802472163

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Pastoral Care in Education Vol. 26, No. 4, December 2008, 231241

Health promoting schools: a New Zealand perspective

Penni Cushman*

University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand (Received 23 May 2008; final version received 7 August 2008)

RPED_A_347384.sgm Taylor and Francis penni.cushman@canterbury.ac.nz PenniCushman 0 400000December 26 Taylor 2008 & Francis Original Article 2008 0264-3944 (print)/1468-0122 Pastoral Care in Education 10.1080/02643940802472163(online)

Downloaded By: [University of Canterbury Library] At: 23:14 29 August 2010

In the last 20 years the health promoting schools movement has gained momentum internationally. Without strong national leadership and direction its development in New Zealand has been ad hoc and sporadic. However, as the evidence supporting the role of health promoting schools in contributing to students health and academic outcomes becomes more robust, their potential can no longer be ignored. This paper sets out to provide an overview of the state of the health promoting schools movement in New Zealand and examines the national framework and process in the light of the international literature. Keywords: health promoting schools; framework; process

Introduction The concept and importance of health promoting schools as a useful vehicle for addressing the physical, social, emotional and spiritual health needs of a nations young people has been recognised in the health sector since its inception in the early 1990s.

Schools can make a significant contribution to increasing the quality of life for their students, staff and wider community by becoming health promoting schools. Becoming a health promoting school provides a way for each school to listen to, and take account of the views of pupils, parents and staff. (HMI Inspectors of Schools, Health Education Board for Scotland, Aberdeen City Council, 1999, p. 2)

More recently, the role of health promoting schools as a contributor to academic success is capturing the attention of the education sector.

Learning and health go hand in hand. Good health of children and young people is a prerequisite for educational achievement. (Ten Dam, 2002, p. 18)

The links between the health of students and their capacity to benefit from educational opportunities are now well established. For example, a recent Canadian study of 5000 1011-yearolds (Florence, Asbridge, & Veugelers, 2008) found the nutritional status of students to be closely linked to their academic outcomes. In the USA, McNeely, Nonnemaker, and Blum (2002), in a longitudinal study of young peoples mental health, found evidence of an association between protective factors such as individual resilience, coping, connectedness to schools, caring adults and peer group and social support, and better educational outcomes. Similarly, the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) cross-national European study (Currie et al., 2004) found that peer support was an important factor in academic

*Email: penni.cushman@canterbury.ac.nz

ISSN 0264-3944 print/ISSN 1468-0122 online 2008 NAPCE DOI: 10.1080/02643940802472163 http://www.informaworld.com

232

P. Cushman

Downloaded By: [University of Canterbury Library] At: 23:14 29 August 2010

achievement and the authors emphasised the need for schools to prioritise activities that promote bonding, as well as decreasing bullying and violent tendencies. A synthesis of reviews by the World Health Organization (WHO) (Stewart-Brown, 2006) found that school-based programmes designed to promote mental health are particularly effective, especially if developed and implemented using approaches common to the health promoting schools approach. As a result of these studies, and other research linking health and academic potential (International Union for Health Promotion and Education, 1999), one might suggest that we have an obligation, academically, in schools to more comprehensively and holistically address health issues. The effects on learning of issues such as bullying, unresolved grief and loss, peer pressure, drug misuse, sexual identity and orientation and the myriad of decisions that young people are confronted with in these areas cannot be underestimated. Commentators in the review of the status of health promoting schools in New Zealand by Allen and Clarke Policy and Regulatory Specialists Limited (2007) noted that: every student should have the right to be educated in a health promoting school (p. 20). Twenty years ago timetabling of classroom health education might have been seen as adequately addressing the health needs of students. It was a good starting point. However, classroom health education is, by itself, unlikely to result in major changes. The importance of a whole school approach of long duration and high intensity, as evidenced in health promoting schools, is emphasised and promoted by the WHO (Stewart-Brown, 2006). Those who actively promote the establishment of health promoting schools would endorse St Leger (1999, p. 56) who stated:

Effort which is directed at improving the health of students and the settings in which they learn also appears to improve and enrich educational outcomes. The health promoting school appears to offer an approach which increases the learning capacity of students. It provides the contextual setting for learning where the individuals health is overtly addressed.

What exactly, is a health promoting school? Despite widespread international recognition of the benefits of health promoting schools a review of recent literature (Rowling, 2005; Turenen, Tossavainen, Jakonen & Vertio, 2006) suggests there is still debate around the precise meaning of a health promoting school and the various theoretical frameworks underpinning health promoting schools in different countries. Of particular import is the need to distinguish between health promotion activities or interventions where health programmes are designed by professionals to address needs they perceive to be of importance to students and the much broader and multifaceted concept of health promoting schools. Consequently, this paper sets out to: (1) clarify the difference between health promotion activities and health promoting schools, (2) identify strategies that have been shown to be integral to the successful implementation of health promoting schools, (3) and, in the process of doing so, highlight their importance and value. Health promotion activities and health promoting schools Many practitioners see these concepts as interchangeable, but they have very different epistemological and ideological bases (Rowling, 2005). Single interventions or events might be identified as health promotion activities (Velde, 2000), but the host school could not, on this basis alone, profess to be a health promoting school. The presence of a strong counselling team, the development of an award winning canteen or the writing of a zero

Pastoral Care in Education

233

tolerance to bullying policy does not, by itself, entitle a school to claim the title of a health promoting school. Moreover a school may boast a large number of interventions and programmes designed to address a range of health issues, but unless they have been implemented as a result of whole school community collaborative engagement in the health promoting schools process they will engender quite different profiles and outcomes from those evident in health promoting schools.

A health promoting school is one in which all members of the school community work together to provide pupils with integrated and positive experiences and structures, which promote and protect their health. This includes both the formal and the informal curriculum in health, the creation of a safe and healthy school environment, the provision of appropriate health services and the involvement of the family and wider community in efforts to promote health. (WHO, 1996, p. 2)

Downloaded By: [University of Canterbury Library] At: 23:14 29 August 2010

In 2007 The International Union for Health Promotion and Education (IUPHE) identified the following 10 principles of a health promoting school (p. 2). (1) Promotes the health and wellbeing of students. (2) Upholds social justice and equity concepts. (3) Involves student activity and empowerment. (4) Provides a safe and supportive environment. (5) Links health and education issues and systems. (6) Addresses the health and wellbeing issues of staff. (7) Collaborates with the local community. (8) Integrates into the schools ongoing activities. (9) Sets realistic goals. (10)Engages parents and families in health education. While it is not difficult to find a plethora of case studies heralding health promotion activities in schools, there is a relative paucity of case studies in the literature profiling schools that demonstrate evidence of each of the 10 principles listed above and their continuance over a period of time. In fact, many schools showcased on the New Zealand health promoting schools national website (http://www.hps.org.nz) not only fall short of meeting all 10 principles listed above but nor do they adhere to criteria identified as integral to the health promoting schools process in New Zealand (Ministry of Health, 2003a). Notwithstanding the apparent lack of cohesion and direction that characterises the New Zealand health promoting schools movement today (Allen and Clarke Policy and Regulatory Specialists Limited, 2007), it is salient to remember that the concept of health promoting schools was unknown 20 years ago, and as its contribution to health and educational outcomes has only recently been clearly established we should applaud those schools that have embraced it. An initiative that requires full consultation and involvement of the wider school community as well as significant changes to the school infrastructure will inevitably be a time-consuming and lengthy business. The New Zealand health promoting schools framework There is a range of theoretical frameworks that are used to underpin health promoting schools in different countries, but because they are all derived from the Ottawa Charter (WHO, 1986) it is not surprising that there are clearly identifiable commonalities between them. This paper uses the health promoting schools framework that has been adopted by

234

P. Cushman

Downloaded By: [University of Canterbury Library] At: 23:14 29 August 2010

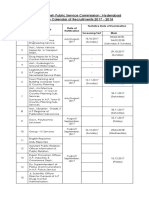

Figure 1. The health promoting schools framework (adapted from Health promoting schools support manual, Ministry of Health, 2003b).

practitioners in New Zealand (see Figure 1) as a basis to identify strategies integral to the successful implementation of the concept. The framework is a useful planning tool to ensure that change is coordinated through the curriculum, the organisation and ethos of the school and links with parents and health providers (Grant, 2005). Each of the three major aspects of the New Zealand framework will be discussed in relation to findings from the literature.

Figure 1. The health promoting schools framework (adapted from Health promoting schools support manual , Ministry of Health, 2003b).

Curriculum Curriculum refers to the classroom teaching around health education and promotion, which in New Zealand is mandated by the Ministry of Education and compulsory from

Pastoral Care in Education

235

Downloaded By: [University of Canterbury Library] At: 23:14 29 August 2010

Years 1 to 10. Worldwide, this aspect of health promoting schools traditionally warrants the greatest emphasis. The most common element is the development of personal health skills and, in line with the Ottawa Charter (WHO, 1986), all frameworks emphasise decision making, problem solving, communication and critical thinking. More recently there has been an even stronger emphasis on interaction and participatory learning methods and students being involved in activities outside the classroom and in the community (St Leger, 1999). While these skills form a strong component of the Health and physical education in the New Zealand curriculum document (Ministry of Education, 1999), there is still a mind shift required in many teachers, to encourage them to move away from traditional content and pedagogy. Health teaching and learning is most effective when a well-designed programme taught by classroom teachers links the curriculum with other health promoting school activities that involve students and families in independent thinking and actions (St Leger, 1999). Learning environments need to foster collaborative and participative health learning and use teaching and learning methods that enable dialogue, critical reflection and social transformation (Turenen et al., 2006, p. 679).

School organisation and ethos School organisation and ethos refers to the physical, social and emotional environment of the school, as well as policies, codes of behaviour, school administration practices and relationships between staff, between staff and students and between staff and the community.

Obesity has been called a normal response to an abnormal environment. (Egger & Swinburn, 1997, p. 477)

Egger and Swinburns provocative statement exemplifies the futility of classroom teaching without an equal or greater emphasis on the environment. In this case it implies the focus of obesity prevention should be a broad environmental approach, rather than a focus on the individual. Recent governmental legislation in New Zealand that will force schools to provide an environment where students have fewer opportunities to consume food high in fat and sugar might be viewed by some as an excellent example of health promotion. However, many New Zealand schools had already arrived at that position by engaging in the health promoting schools process whereby a similar, or preferably even more rigorous, food policy resulted from the informed choice of the whole school community students, teachers and parents. While resulting in similar school policies, the knee-jerk, governmental (top-down approach) reaction to food issues caused anger and resentment, feelings of powerlessness, reference to teachers as food police and media attention paid to the expectation that schools should solve societal problems. On the other hand, schools that have taken up the issue of school food choices to address a range of issues, including those related to weight as well as academic potential, and have as a school community shared visions and developed a plan of action to work towards their vision are modelling appropriate and empowering participatory strategies, integral to the health promoting schools process, to students. Resultant policies might be identical to that imposed on schools by the government but engender very different feelings and outcomes. The school social environment is difficult to assess, but there is enough evidence to suggest that it is a key element in health promoting schools (IUPHE, 1999; McNeely et al., 2002; Wyllie, Postlethwaite, & Casey, 2000). In the promotion of mental health an essential component of the health promoting schools approach is dependent on the climate and

236

P. Cushman

Downloaded By: [University of Canterbury Library] At: 23:14 29 August 2010

ethos of the school reflecting a fundamental stance that empowers individuals and groups to fully participate and make a positive contribution to promoting and supporting mental and emotional well-being (Ministry of Health, 2003b). The quality of the social environment of the school has a direct relation to the connectedness that students and staff have to schools. The psycho-social environment of the school covers a myriad of contributing aspects and includes support mechanisms such as the availability of counselling, wellness services, access to and relationships with community services, relationships between teachers, relationships between boards of trustees, principals and teachers, acceptance and celebration of cultural diversity and parental/care-giver involvement in the school. Teachers in the 63 schools involved in the Health Promoting Schools Pilot Project in New Zealand (Wyllie et al., 2000) saw their biggest challenge to be the maintenance of the ethos of the whole school approach long enough for it to become embedded within the school culture. Without this, and concomitant changes in school administration and teaching, there is less likelihood of a long-term impact on students (Simpson & Freeman, 2004; Turenen et al., 2006). The Health Promoting Schools Pilot Project also found strong support from school management to be vital to success (Wyllie et al., 2000). A health promoting school needs leadership that takes a holistic view of health and is committed to improving the health and well-being of all students, teachers and the wider community (Scottish Health Promoting Schools Unit, 2005). Without this support it is unlikely that the ethos and organisational structures conducive to health promoting schools can be established. This is not to say that the school principal is responsible for leadership of the process. Rather, Turenen et al.s (2006) model emphasises a bottom-up, rather than top-down, strategy for change ensuring all those involved in the school actively participate in working for change through democratic dialogue. This collaborative environment necessarily includes trust, open communication, sharing of information, participatory decision making, support for critical reflection and the encouragement to question and value differences and to challenge and debate teaching and learning issues (Turenen et al., 2006). The school health coordinators role is central to success and the allocation of time for working with staff, service providers and community representatives is essential. Links with parents and health providers Links with parents and health providers includes the process of consulting and involving the wider school community and the development of positive working relationships with health and welfare services. While the various international frameworks for health promoting schools stress the importance of partnerships with the local community, the energy required for the development and maintenance of these relationships has resulted in huge variation in their intensity and effectiveness (St Leger, 1999; Wylie et al., 2000). Turenen et al. (2006) found that if energy is not expended to ensure parental involvement and commitment, health promoting schools have little chance of success. When efforts to establish relationships reflect a sincere desire to engage parents and the community as partners however, studies show a greater likelihood of a positive response and outcome (Henderson & Mapp, 2002). Community members need assurance that the responsibility for students health in schools is a collaborative enterprise and in health promoting schools the philosophy of partnership ensures that this responsibility is shared. Strategies that have been successfully employed to develop partnerships with families in New Zealand are home visits, neighbourhood walks to identify key issues in the community, focus groups and other small meetings, parent education and

Pastoral Care in Education

237

meetings with appropriate community representatives (Henderson & Mapp, 2002). The worst case scenario is when parents and community members are used simply to rubber stamp decisions. School communities comprised of a number of ethnic groups present some schools with a challenge, but representation of all groups in the health promoting schools process is essential. In New Zealand this has required the health promoting schools initiative to pay particular attention to the partnership with Maori. Despite this emphasis, Wyllie et al. (2000) identified aspects of Maori participation as not having been sufficiently well thought through to enable full participation and functioning of this sector of the school community. Without sufficient time and energy devoted to probing cultural variations it is not possible to foster positive and productive connections between culturally diverse parents and schools. In addition, Henderson and Mapp (2002) found that the non-involvement of parents in school activities is unlikely to reflect a dont care attitude. Rather, it reflects the need for schools to at times explore alternative avenues of contact that better reflect a particular communitys priorities. If health promoting schools are to maximise their potential the health promoting schools concept and process needs to be widely understood by everyone in the community (Gray, Young, & Barnekow, 2006). Moreover, this is a prerequisite if the whole school community is to work collaboratively towards their shared vision. The APPLE study (Williden et al., 2006), conducted in three small communities in New Zealand, provided us with some useful insights into the importance of schoolcommunity collaboration. For example, schools and parents views around an issue, or contributing factors to an issue, are not necessarily the same. In the APPLE study lack of time was perceived by school principals as a major barrier with respect to parental involvement in schools. However, the researchers found that parents did not find time a barrier, and a later request by 40% of the parents for information led the researchers to cite lack of knowledge as a major contributing factor. In the same study schools were reluctant to ban foods from the canteens and blamed parents for the undesirable food choices their children were making. Parents, on the other hand, thought the issue of food choices to be the schools responsibility and favoured the banning of certain foods. It is also important that the education and health sectors work closely together to develop strategies that are consistent with the needs of each school community (St Leger, 1999). It is evident that intersectorial collaboration facilitates the comprehensiveness of programmes and has the potential for significant health gains. In New Zealand there has been little collaboration between the health and education sectors in the development of health promoting schools (Grant, 2005). Currently it appears that each sector has a poor understanding of how the other sector works and exactly what they can contribute. Unfortunately, to date there are few studies that show how these relationships can be effectively established and maintained (St Leger, 1999), but it is clear that there needs to be a joint investment from both the health and educational sectors at governmental level if the health promoting schools movement is to grow in a less ad hoc and sporadic fashion (Allen and Clarke Policy and Regulatory Specialists Limited, 2007). The New Zealand health promoting schools process The following diagram illustrates the health promoting schools process recognised and adopted within New Zealand schools (Ministry of Health, 2003a). The nine stages of implementation are based on internationally recognised models of best practice [International Planning Committee of the European Network of Health Promoting Schools (IPC ENHPS), 2004].

Figure 2. The health promoting schools process (adapted from Health promoting schools support manual , Ministry of Health, 2003b).

Downloaded By: [University of Canterbury Library] At: 23:14 29 August 2010

238

P. Cushman

Downloaded By: [University of Canterbury Library] At: 23:14 29 August 2010

Figure 2. The health promoting schools process (adapted from Health promoting schools support manual, Ministry of Health, 2003b).

As previously mentioned, the introduction of the concept of health promoting schools in New Zealand has to date been the responsibility of the health sector. Health promoting school advisors, based in and financially supported by regional health authorities, have supported their local schools in awareness raising and seeking a commitment to the concept of health promoting schools from the schools leaders and governing bodies. As the health sector have historically entered schools to administer medical care and provide guidance around physical health issues, their transition to the role of health promoters has at times met with resistance from school staff, who have seen health education as the prerogative of teachers. Internationally the role of developing a health promoting school has generally been afforded to a reasonably experienced and influential member of staff, working with a

Pastoral Care in Education

239

group of committed colleagues (IPC ENHPS, 2004). In New Zealand it is more common for the health promoting schools advisor to take a leading role and work with a teacher who believes in the concept of health promoting schools. Together they work to raise awareness in the school and wider school community of the value of becoming a health promoting school. Allen and Clarke Policy and Regulatory Specialists Limited (2007) pointed out that the New Zealand education sector can no longer abdicate this responsibility to the health sector and needs to take a far stronger and more active leadership role. The composition of the health promoting schools team varies from school to school but its structure and subsequent team dynamics have a major influence on the likelihood that the team can effectively influence school policies and practices. It is crucial that each segment of the school community is well represented students, parents, the schools leadership and governing body, teachers and service providers. Each representative is charged with the responsibility of consulting with the body they represent and ensuring each group feels that their views are respectfully listened to and considered as goals are set and worked towards. The role of students in the health promoting schools process has been the focus of a number of studies in recent years (Jensen & Simovska, 2005; Turenen et al., 2006). The Protocols and Guidelines for Health Promoting Schools (IUHPE, 2007, p. 2) identified student participation and empowerment as one of the 10 principles embodied by a health promoting school. Without continued student input in the health promoting schools process from the time of its inception in the school and their active representation and participation on the health promoting schools team the likelihood of the development of initiatives that meet students needs and interests are jeopardized. A perusal of the national website (http:// www.hps.org.nz), however, suggests a top-down approach is not uncommon in New Zealand schools. If one of the outcomes of a health promoting school is to ensure students feel they have some sense of ownership of the life of the school (IUHPE, 2007) then this aspect of the process needs attention. There is now a plethora of resources available to guide and support schools as they embark on the health promoting schools journey (Gray et al., 2006; IPC ENHPS, 2004; IUHPE, 2007; Ministry of Health, 2003a, 2003b; Scottish Health Promoting Schools Unit, 2005). A knowledge of and familiarity with these materials helps to decrease the likelihood of confronting some of the challenges that have been alluded to throughout this paper. Although comprehensive and user friendly resources have been freely available to schools for a number of years, there are more complex hurdles to be jumped before the concept of health promoting schools becomes an integral feature of all New Zealand schools. Without significant, positive multilevel contributions the potential of the health promoting schools movement will not be realised. We owe it to future generations in terms of both their health and academic potential to make sure that health promoting schools are seen as an essential strategy in student development and success.

Downloaded By: [University of Canterbury Library] At: 23:14 29 August 2010

References

Allen and Clarke Policy and Regulatory Specialists Limited. (2007). Health promoting schools: A framework for a national approach. Wellington: Allen and Clarke Policy and Regulatory Specialists. Currie, C., Roberts, C., Morgan, A., Smith, R., Settertobulte, W., Samdal, O., & Rasmussen, V. (2004). Young peoples health in context. Health behaviour in school-aged children: International report from the 2001/2002 survey. Health Policy for Children and Adolescents no. 4. Copenhagen: World Health Organization. Egger, G., & Swinburn, B. (1997). An ecological approach to the obesity pandemic. British Medical Journal, 315, 477480.

240

P. Cushman

Florence, M., Asbridge, M., & Veugelers, P. (2008). Diet quality and academic performance. Journal of School Health, 78 (4), 209215. Grant, S. (2005). Tipu Ka Rea/to grow, expand and multiply: An operational model for developing sustainable health-promoting schools in Aotearoa New Zealand. Education and Health, 23(3), 4446. Gray, G., Young, I., & Barnekow, V. (2006). Developing a health promoting school. A practical resource for developing effective partnerships in school health, based on the experience of European Network of Health Promoting Schools. Retrieved June 4, 2007, from World Health Organization web site: http://www.euro.who.int/ENHPS Henderson, A., & Mapp, K. (2002). A new wave of evidence: The impact of school, family and community connections on student achievement. Austin, TX: National Centre for Family and Community Connections with Schools. HMI Inspectors of Schools, Health Education Board for Scotland, Aberdeen City Council. (1999). A route to health promotion: Self-evaluation using performance indicators. Allen and Clarke Policy and Regulatory Specialists LimitedHMI Audit Unit. Retrieved May 1, 2008, from HMI Scotland web site: http://http://www.hmie.gov.uk/documents International Planning Committee of the European Network of Health Promoting Schools (IPC ENHPS). (2004). Promoting health in second level schools in Europe: A practical guide. Geneva: World Health Organization. International Union for Health Promotion and Education (IUHPE). (1999). The evidence of health promotion effectiveness. Paris: IUHPE. International Union for Health Promotion and Education (IUHPE). (2007). Protocols and guidelines for health promoting schools. Paris: IUHPE. Jensen, B., & Simovska, V. (2005). Involving students in learning and health promotion processes clarifying why? what? and how? Promotion and Education, 12(3/4), 150156. McNeely, C., Nonnemaker, J., & Blum, R. (2002). Promoting student connectedness to school: Evidence from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Journal of School Health, 72(4), 138146. Ministry of Education. (1999). Health and physical education in the New Zealand curriculum. Wellington: Learning Media. Ministry of Health. (2003a). The health promoting schools process. Wellington: Ministry of Health. Ministry of Health. (2003b). The health promoting schools support manual. Wellington: Ministry of Health. Rowling, L. (2005). Dissonance and debates encircling health promoting schools. Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 16(1), 5557. Scottish Health Promoting Schools Unit. (2005). Being well doing well: A framework for health promoting schools in Scotland. Edinburgh: Scottish Health Promoting Schools Unit. Simpson, K., & Freeman, R. (2004). Critical health promotion and education a new research challenge. Health Education and Research Theory and Practice, 19(3), 340348. St Leger, L. (1999). The opportunities and effectiveness of the health promoting primary school in improving child health a review of the claims and evidence. Health Education Research, 14(1), 5169. Stewart-Brown, S. (2006). What is the evidence on school health promotion in improving health or preventing disease and, specifically, what is the effectiveness of the health promoting schools approach? Copenhagen: World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. Ten Dam, G. (2002, September). Effectiveness in health education. Paper presented to the Education and Health in Partnership Conference, Egmond aan Zee, The Netherlands. Turenen, H., Tossavainen, K., Jakonen, S., & Vertio, H. (2006). Did something change in health promotion practices? A three-year study of Finnish European Network of Health Promoting Schools. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 12(6), 675692. Velde, M. (2000). All in school should help in health. The New Zealand Education Gazette, 79(19), 3. Williden, M., Taylor, R., McAuley, K., Simpson, J., Oakley, M., & Mann, J. (2006). The APPLE project: An investigation of the barriers and promoters of healthy eating and physical activity in New Zealand children aged 512 years. Health Education Journal, 65(2), 135148. World Health Organization. (1986). The Ottawa Charter. Retrieved June 4, 2007 from World Health Organization web site: http:////www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/previous/ ottawa/en/

Downloaded By: [University of Canterbury Library] At: 23:14 29 August 2010

Pastoral Care in Education

241

World Health Organization (1996). Health promoting schools, Series 5, Regional guidelines. A framework for action. Manilla: World Health Organization. Wyllie, A., Postlethwaite, J., & Casey, E. (2000). Health promoting schools in northern region: Overview of evaluation findings of pilot project. Auckland, New Zealand: Phoenix Research.

Downloaded By: [University of Canterbury Library] At: 23:14 29 August 2010

You might also like

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Extraordinary GazetteDocument10 pagesExtraordinary GazetteAdaderana OnlineNo ratings yet

- Mbs KatalogDocument68 pagesMbs KatalogDobroslav SoskicNo ratings yet

- Injection MouldingDocument241 pagesInjection MouldingRAJESH TIWARINo ratings yet

- EDAH EnglishDocument2 pagesEDAH EnglishMaría SanchoNo ratings yet

- BRC1B52-62 FDY-F Ducted Operation Manual - OPMAN01!1!0Document12 pagesBRC1B52-62 FDY-F Ducted Operation Manual - OPMAN01!1!0Justiniano Martel67% (3)

- CRM McDonalds ScribdDocument9 pagesCRM McDonalds ScribdArun SanalNo ratings yet

- Deloitte Uk Mining and Metals DecarbonizationDocument10 pagesDeloitte Uk Mining and Metals DecarbonizationfpreuscheNo ratings yet

- Grundfos Data Booklet MMSrewindablesubmersiblemotorsandaccessoriesDocument52 pagesGrundfos Data Booklet MMSrewindablesubmersiblemotorsandaccessoriesRashida MajeedNo ratings yet

- EDC MS5 In-Line Injection Pump: Issue 2Document57 pagesEDC MS5 In-Line Injection Pump: Issue 2Musharraf KhanNo ratings yet

- 10.0 Ms For Scaffolding WorksDocument7 pages10.0 Ms For Scaffolding WorksilliasuddinNo ratings yet

- SET 2022 Gstr1Document1 pageSET 2022 Gstr1birpal singhNo ratings yet

- Compensation ManagementDocument2 pagesCompensation Managementshreekumar_scdlNo ratings yet

- Practice Problems Mat Bal With RXNDocument4 pagesPractice Problems Mat Bal With RXNRugi Vicente RubiNo ratings yet

- Vicat Apparatus PrimoDocument10 pagesVicat Apparatus PrimoMoreno, Leanne B.No ratings yet

- Tomography: Tomography Is Imaging by Sections or Sectioning Through The Use of AnyDocument6 pagesTomography: Tomography Is Imaging by Sections or Sectioning Through The Use of AnyJames FranklinNo ratings yet

- This Unit Group Contains The Following Occupations Included On The 2012 Skilled Occupation List (SOL)Document4 pagesThis Unit Group Contains The Following Occupations Included On The 2012 Skilled Occupation List (SOL)Abdul Rahim QhurramNo ratings yet

- Effect of Moisture Content On The Extraction Rate of Coffee Oil From Spent Coffee Grounds Using Norflurane As SolventDocument8 pagesEffect of Moisture Content On The Extraction Rate of Coffee Oil From Spent Coffee Grounds Using Norflurane As SolventMega MustikaningrumNo ratings yet

- Cash and Cash Equivalents ReviewerDocument4 pagesCash and Cash Equivalents ReviewerEileithyia KijimaNo ratings yet

- Richard Teerlink and Paul Trane - Part 1Document14 pagesRichard Teerlink and Paul Trane - Part 1Scratch HunterNo ratings yet

- CH 13 RNA and Protein SynthesisDocument12 pagesCH 13 RNA and Protein SynthesisHannah50% (2)

- Latihan Soal Bahasa Inggris 2Document34 pagesLatihan Soal Bahasa Inggris 2Anita KusumastutiNo ratings yet

- Crime Free Lease AddendumDocument1 pageCrime Free Lease AddendumjmtmanagementNo ratings yet

- Cooling SistemadeRefrigeracion RefroidissementDocument124 pagesCooling SistemadeRefrigeracion RefroidissementPacoNo ratings yet

- Ecg Quick Guide PDFDocument7 pagesEcg Quick Guide PDFansarijavedNo ratings yet

- Management of Developing DentitionDocument51 pagesManagement of Developing Dentitionahmed alshaariNo ratings yet

- APPSC Calender Year Final-2017Document3 pagesAPPSC Calender Year Final-2017Krishna MurthyNo ratings yet

- 4th Summative Science 6Document2 pages4th Summative Science 6brian blase dumosdosNo ratings yet

- LWT - Food Science and Technology: A A B ADocument6 pagesLWT - Food Science and Technology: A A B ACarlos BispoNo ratings yet

- Community Medicine DissertationDocument7 pagesCommunity Medicine DissertationCollegePaperGhostWriterSterlingHeights100% (1)

- Mass SpectrometryDocument49 pagesMass SpectrometryUbaid ShabirNo ratings yet