Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Miami's Colored Over Segregation

Uploaded by

sfwhitehornOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Miami's Colored Over Segregation

Uploaded by

sfwhitehornCopyright:

Available Formats

Miami's Colored-Over Segregation:

Segregation, Interstate 95 + Miami's African American Legends

Nathaniel Q. Belcher

Nathaniel Belcher's Miami's Colored-Segregation: Segregation, Interstate 95 and Miami's African American Legends is an investigation into one of Miami's and perhaps the state of Florida's most historical prominent African American communities. While this publication celebrates the many triumphs of a once successful African American community with its foundation stemming from the production of rail lines, it reveals the conflict provoked by suburbanization and the construction of one of the most expensive infrastructural projects that is Interstate 95. Overtown's history began with landowner baroness, Julia Tuttle, and railroad magnate Henry M. Flagler's interest in the expansion of railroads south of the Miami River and the initiation of a new city. This new city would later grow into a world class beach resort city boasting recreation, an integral international hub, and a cultural point in exotic South Florida known as Miami. African Americans found great opportunity working for the railroads and the construction of the Biltmore Hotel and had established its own self sufficient, thriving community. Ella Fitzgerald would frequent its juke joints after performing in segregated Miami Beach clubs as well as a young Muhammed Ali could be seen jogging from the Elizabeth Hotel to fights in Miami Beach. Segregation was ruled unconstitutional in 1947 and while this ruling was a triumph in gaining momentum for the fight for racial equality, this would initiate urban conflict and the demise of Overtown.This ruling not only affected the community of Overtown, but many urban centers across the United States. The middle to upper class flight to the suburbs escaping urban density, racial conflict, and decay caused a need for connecting urban financial centers to the city's growing extremities. This flight in concert with inflated prices, redlining, and the influx of Cubans caused a swell in the density of Overtown which caused a significant demand for housing. This also began the deterioration of a destination and icon for African American achievement and sustainability. Shotgun homes were replaced with dense concrete structures maximizing on units and minimizing space. Poorly ventilated dense housing projects intertwined with developmental infrastructural projects including canals to carry waste and drain the Everglades created an urban jungle of discomfort and further separated Overtown from vital services. Under Eisenhower's Interstate initiative, Overtown was virtually split by the massive stoich and monumental [ 7 stories tall ] Interstate 95. Its action of carving and suspending itself above the landscape served as a visual cue of division ,obstruction, and the influence of interface. More interesting, interstate 95 is reduced to a scenic four lane palm lined boulevard in Miami's most affluent community, Coral Gables. Belcher reveals attempts to regain, rehabilitate, and connect multiple corridors split by Interstate-95. Palm tree lined center islands, gardens, outdoor theaters, pedestrian malls, and even folkloric villages have all been attempts at reclaiming this victimized space. These attempts are presented as urban sutures reclaiming a spatial nostalgia but not successful in obliterating or even blurring the boundary between the interstate and Overtown. The author argues for a consciousness in understanding the negative implications of infrastructure and its socio-economical divisive nature while unveiling its structure of power in its ability to evoke

permanence amongst the scape of Miami. It becomes a symbol of escape and destruction. Keeping in mind the political agendas of suburbanization that would later form other regions such as Fort Lauderdale and Homestead, Overtown has become desolate, defunct, and a symbol of what was and what will never be.This text reveals a common thread amongst all inner city urban centers and their minimal impact on infrastructural decisions due to the lack of socio-economic and political interface. Critique: I am attracted to the visual imagery that Belcher provokes about pre-integrated Overtown. Visions of broad thoroughfares lit with signs of theaters, hotels, and restaurants where African Americans seemed to enjoy a quality of life quite opposite of other regions of predominantly African American communities come to mind. He gains significant emotional traction as he African American Legends to the celebration of Overtown as a premier destination. The narrative in which he describes the evolution of the city and it's importance to the construction of railroads is integral in understanding the stability that already existed. Belcher takes a phenomenological and theoretical approach at allowing the reader to further understand the bridge. Not only do we understand the bridge as it relates to a strategy of escape and destruction but its hierarchy amongst the natural scape of Miami; the way in which it effects the horizon at dusk and dawn. My senses are awakened at visualizing this man-made intervention as I have too viewed this same moment with my own eyes living in the city of Miami. I-95 and projects alike not only reveal their divisive power in nature but their power as a structure of permanence amidst a shifting landscape. While I would argue that Belcher is phenomenal at attracting emotional investment in the story of Overtown, I would argue that Belcher does not challenge us with ways in which a solution can challenge the way the space is conceptualized. I was left with an unsolved problem and only marginal solutions carrying a tone of inevitable failure. In also understanding the contextual events that took place across America due to Eisenhower's interstate system do we begin to understand these implications not just in Overtown but threads of displacement that occurred within other regions across the United States. Were other regions successful in operating amid massive infrastructural projects? Overtown was a historical district for African Americans but history, as well as the text, reveals to us that the Cuban population in South Florida and Overtown substantially multiplied itself. How did practices of redlining, integration, and the building of Interstate 95 affect the Cuban population? The scope at which we problematize Interstate-95 is limited. Was Interstate 95 the only production that had adverse results on the development of Overtown? The publication reveals to us that Overtown did exist at the margin of an affluent community. What were the social interactions at and around this boundary? Was there tension, fear, or conflict? What strategies of interface prevented I-95 from towering over their communities? This publication presents Overtown as if it existed in a vacuum with no contextual influences outside of the Interstate 95. What about Overtown's relation to the Port of Miami, the financial district, Miami Beach and surround communities? Was this an isolated event in which an entire community was affected or were there others existing in the wake of its inception?

You might also like

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Article 11.21.11Document22 pagesArticle 11.21.11sfwhitehornNo ratings yet

- Bibliography: CCA March Research Lab Fall 2011 Instructor: Neal SchwartzDocument2 pagesBibliography: CCA March Research Lab Fall 2011 Instructor: Neal SchwartzsfwhitehornNo ratings yet

- Bibliography: CCA March Research Lab Fall 2011 Instructor: Neal SchwartzDocument2 pagesBibliography: CCA March Research Lab Fall 2011 Instructor: Neal SchwartzsfwhitehornNo ratings yet

- Ideogram 11.21.11Document1 pageIdeogram 11.21.11sfwhitehornNo ratings yet

- Article: Bufalini Map of Rome, 1551 Source:nolli - Uoregon.eduDocument10 pagesArticle: Bufalini Map of Rome, 1551 Source:nolli - Uoregon.edusfwhitehornNo ratings yet

- Ideogram10 21 11Document1 pageIdeogram10 21 11sfwhitehornNo ratings yet

- 10.6.11 AbstractDocument1 page10.6.11 AbstractsfwhitehornNo ratings yet

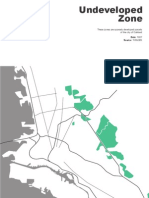

- Green ZoneDocument1 pageGreen ZonesfwhitehornNo ratings yet

- Light Blue ZoneDocument1 pageLight Blue ZonesfwhitehornNo ratings yet

- IdeogramDocument1 pageIdeogramsfwhitehornNo ratings yet

- Architecture and Social Change Summary and CritiqueDocument2 pagesArchitecture and Social Change Summary and CritiquesfwhitehornNo ratings yet

- IdeogramDocument1 pageIdeogramsfwhitehornNo ratings yet

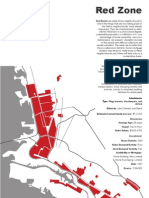

- Red ZoneDocument1 pageRed ZonesfwhitehornNo ratings yet

- Whitehorn - Shawn 9.22.11Document1 pageWhitehorn - Shawn 9.22.11sfwhitehornNo ratings yet

- Blue ZoneDocument1 pageBlue ZonesfwhitehornNo ratings yet

- Sites of MemoryDocument3 pagesSites of MemorysfwhitehornNo ratings yet

- White Papers, Black MarksDocument2 pagesWhite Papers, Black MarkssfwhitehornNo ratings yet

- SWhitehorn - Thesis Abstract 9.7.11Document2 pagesSWhitehorn - Thesis Abstract 9.7.11sfwhitehornNo ratings yet

- BibliographyDocument1 pageBibliographysfwhitehornNo ratings yet

- Shawn Whitehorn JR.: California College of The Arts Thesis Research Lab Instructor: Neal SchwartzDocument11 pagesShawn Whitehorn JR.: California College of The Arts Thesis Research Lab Instructor: Neal SchwartzsfwhitehornNo ratings yet

- Shawn Whitehorn JR.: CCA Fall 2011 Thesis Research Lab/Seminar Instructor: Neal SchwartzDocument5 pagesShawn Whitehorn JR.: CCA Fall 2011 Thesis Research Lab/Seminar Instructor: Neal SchwartzsfwhitehornNo ratings yet

- Book IntroductionDocument3 pagesBook IntroductionsfwhitehornNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- 9m.2-L.5@i Have A Dream & Literary DevicesDocument2 pages9m.2-L.5@i Have A Dream & Literary DevicesMaria BuizonNo ratings yet

- Predictive Tools For AccuracyDocument19 pagesPredictive Tools For AccuracyVinod Kumar Choudhry93% (15)

- Business Finance and The SMEsDocument6 pagesBusiness Finance and The SMEstcandelarioNo ratings yet

- Reith 2020 Lecture 1 TranscriptDocument16 pagesReith 2020 Lecture 1 TranscriptHuy BuiNo ratings yet

- Chapter One Understanding Civics and Ethics 1.1.defining Civics, Ethics and MoralityDocument7 pagesChapter One Understanding Civics and Ethics 1.1.defining Civics, Ethics and Moralitynat gatNo ratings yet

- Java ReviewDocument68 pagesJava ReviewMyco BelvestreNo ratings yet

- GRADE 1 To 12 Daily Lesson LOG: TLE6AG-Oc-3-1.3.3Document7 pagesGRADE 1 To 12 Daily Lesson LOG: TLE6AG-Oc-3-1.3.3Roxanne Pia FlorentinoNo ratings yet

- 19 Amazing Benefits of Fennel Seeds For SkinDocument9 pages19 Amazing Benefits of Fennel Seeds For SkinnasimNo ratings yet

- Abnormal PsychologyDocument13 pagesAbnormal PsychologyBai B. UsmanNo ratings yet

- Ergatividad Del Vasco, Teoría Del CasoDocument58 pagesErgatividad Del Vasco, Teoría Del CasoCristian David Urueña UribeNo ratings yet

- Islamic Meditation (Full) PDFDocument10 pagesIslamic Meditation (Full) PDFIslamicfaith Introspection0% (1)

- Chhabra, D., Healy, R., & Sills, E. (2003) - Staged Authenticity and Heritage Tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 30 (3), 702-719 PDFDocument18 pagesChhabra, D., Healy, R., & Sills, E. (2003) - Staged Authenticity and Heritage Tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 30 (3), 702-719 PDF余鸿潇No ratings yet

- Applied Nutrition: Nutritional Consideration in The Prevention and Management of Renal Disease - VIIDocument28 pagesApplied Nutrition: Nutritional Consideration in The Prevention and Management of Renal Disease - VIIHira KhanNo ratings yet

- Paediatrica Indonesiana: Sumadiono, Cahya Dewi Satria, Nurul Mardhiah, Grace Iva SusantiDocument6 pagesPaediatrica Indonesiana: Sumadiono, Cahya Dewi Satria, Nurul Mardhiah, Grace Iva SusantiharnizaNo ratings yet

- A Terrifying ExperienceDocument1 pageA Terrifying ExperienceHamshavathini YohoratnamNo ratings yet

- Musculoskeletan Problems in Soccer PlayersDocument5 pagesMusculoskeletan Problems in Soccer PlayersAlexandru ChivaranNo ratings yet

- Infusion Site Selection and Infusion Set ChangeDocument8 pagesInfusion Site Selection and Infusion Set ChangegaridanNo ratings yet

- Foxit PhantomPDF For HP - Quick GuideDocument32 pagesFoxit PhantomPDF For HP - Quick GuidekhilmiNo ratings yet

- Conversation Between God and LuciferDocument3 pagesConversation Between God and LuciferRiddhi ShahNo ratings yet

- Espinosa - 2016 - Martín Ramírez at The Menil CollectionDocument3 pagesEspinosa - 2016 - Martín Ramírez at The Menil CollectionVíctor M. EspinosaNo ratings yet

- Simple Future Tense & Future Continuous TenseDocument2 pagesSimple Future Tense & Future Continuous TenseFarris Ab RashidNo ratings yet

- Eternal LifeDocument9 pagesEternal LifeEcheverry MartínNo ratings yet

- Your Free Buyer Persona TemplateDocument8 pagesYour Free Buyer Persona Templateel_nakdjoNo ratings yet

- Information Theory Entropy Relative EntropyDocument60 pagesInformation Theory Entropy Relative EntropyJamesNo ratings yet

- SUBSET-026-7 v230 - 060224Document62 pagesSUBSET-026-7 v230 - 060224David WoodhouseNo ratings yet

- Clearing Negative SpiritsDocument6 pagesClearing Negative SpiritsmehorseblessedNo ratings yet

- Blunders and How To Avoid Them Dunnington PDFDocument147 pagesBlunders and How To Avoid Them Dunnington PDFrajveer404100% (2)

- The Role of Mahatma Gandhi in The Freedom Movement of IndiaDocument11 pagesThe Role of Mahatma Gandhi in The Freedom Movement of IndiaSwathi Prasad100% (6)

- Great Is Thy Faithfulness - Gibc Orch - 06 - Horn (F)Document2 pagesGreat Is Thy Faithfulness - Gibc Orch - 06 - Horn (F)Luth ClariñoNo ratings yet