Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Lugubrious Game DALI Essay8 24289K

Uploaded by

Phillip John O'SullivanOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Lugubrious Game DALI Essay8 24289K

Uploaded by

Phillip John O'SullivanCopyright:

Available Formats

Phillip OSullivan The Lugubrious Game The Writers and Artists writings about this painting in the career

of Salvador Dali and Surrealism Born May 11, 1904 Paradoxically we can see in Salvador Dalis art a Marquis de Sade Justine like emphasis on violence and depravity as a way of liberation and freedom for the imagination. A really dead imagination to Dali is one of convention lacking all surprise, innovation or shock-of-recognition: this type of conventional art is/was all around the art community even/then and now in Spain. Dalis young adult friend Frederico Garcia Lorca and he agreed and utilized imagery of decay and death in their drawings, poems and articles in order to emphasize this and shock the viewer or reader into seeing more sharply by these devices; opening their eyes by threatening the view of what they saw. Ending his period with the army in 1927Dali summered in Cadaques with Garcia Lorca. While there Dali wrote a poem titled Saint Sebastin, later published in LAmic de les Aris and the newspaper El Gallo. A drawing being subsequently produced. Around this time in a letter from 1926 he wrote out of the San Sebastia theme this single eye, suddenly enlarged, encompasses

a whole scene of the bottom and surface of an ocean in which all poetic suggestions navigate, and where all the plastic possibilities are stabilized (Finkelstein:30) The drawing has a pronounced encephalic aspect in a headless torso with a fish apparatus emerging from the featureless absence. It has no head.1 Arabic transparent typeface

As quoted in haim finkelstein art and writing 1927 1942 salvador vdali san sebastia letter this single eye, suddenly enlarged, encompasses a whole scene of the bottom and surface of an ocean in which all poetic suggestions navigate, and where all the plastic possibilities are stabilized page 30 finkelstein.1926 This headless/heedless aspect of Dalis art opens up Freudian possibilities free of moral censorship and

1

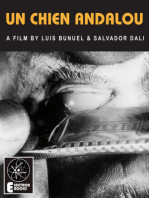

The well crafted poetic prose made an impact on the Catalan literati. Dali created a metaphor of the arrow-riddled saint discovering armour in his faith and the artist carefully letting his imageryripen, and Dali elaborated on his ideas about painting being more accurate than the reality of photography. This argues for the greater psychological effect possible in art. Dali is beginning in these Barcelona/Madrid years to probe into his characteristic paranoid critical method of painting. He had earlier adopted a foppish dandy personae for himself as we see first in self portrait with Raphealish Neck and in a self portrait drawing from 1922. (illustrate) These ideas of ant decay, death and rotting donkeys, the putrescent priests of convention (see also Batailles Lord Ausch writing.) is also prevalent in the extremely artistic Film En Chien Andalu (The Andalusian Dogs) co-created in 1928-9 together with Bunuel another of Dalis Madrid artschool friends, with whom he wrote the shooting script and contributed graphic ideas including the famous cloudsun/eye-cutting scene early in the film. These three visual artists, intelligent, sensitive and culturally aware, inhabited a kind of Madrid Art Academy and Barcellona artworld anti-art faction, they were against calm, ordered, sensible and sentimental art. They were aware of Picasso, Miro and the Paris artscene, collage and photography so much that cubism to them, was, in being the most recently established avant garde style, that it was this advanced art that had become dead, conventional, and must be overthrown for them to make their own mark. Even this modern art was putrid, rotting and had to be expunged by shocking devices and strategies. Despite their own moviemaking and wide open to all kinds of creative allowances. It is Bataille, whom he later meets in Paris, who is philosophically closer to Dali at this point, than the Surrealist leader Andre Breton later. Althought, realistically it is to Lorca whom he owes a closer contemporary creative partnership in Spain.

incorporation of photagraphic devices such as in their own collaging. Notwithstanding this appreciation and cooptation the necessity to kill the old rot was paramount. For this they armed themselves with de Sade, Freud and Surrealism. To create a valid Spanish surrealism required an opposite turgid sentimental realism to which their own extreme de Sade hyper-reality could be opposed. To name the name the name of their own other (for all is other to the other; another other-as it were, though not to be too precious or facetious about this obvious philosophical point) their opposite numbers were competitively close and almost allied in an overall artworld project. Yet sufficiently different from their own coalescing creative purpose as to function fully as other; another cultural stream that they could communicate with, understand and debate with. The instrument of that artistic debate was the abstraction builtinto cubism, futurism, impressionism and expressionism: all of them denying classic codes of realism, scientific psychology and narrative; all essential ingredients in the poems, films and drawings they were making. They were a kind of proto-surrealist group or para-Dada; working alongside a French anti-art movement from within Spain. Their chosen talisman image was that of violence, putrefaction, death, deacay and forbidden sexualities. Everything else was rotten and culturally in a state of decay. One image in particular would stand out amoung the Orphic encephalic torsos and knifelike vaginal/female toothed visions such as appears in Honey is Sweeter than Blood, the San Sebastian encephalic drawing and Apparatus with Hand. It is the image of the ant strewn corpse, the ants sucking blood juices from a rotting field donkey in the Catalan countryside; a scene both Lorca and Dali had frequently seen while out walking. This putrefaction of the rotting donkey kind appears to be a Dali expression also for what Clement Greenberg would call, in another context, Kitsch. Although, as one can easily imagine: each today could apply the term/s to the other. The vividness of this deadly talismanic device and its equally associated scandalous tropes (encephalic torsos, dead heads, explicit

Freudian sex organs, burning objects, random correlations, bodily distortions and erotic distortions generally) would eventually be the miniaturist tool to prise open the Parisian artworld to them. The minutiae of shock and perverse seductions, coprophilic excrement, overt shit and sabotaging fingerings (as uncovered here) would be his futureanti-art, anti-research (he failed art theory in the Madrid academy) approach to conquering the Paris art Gallery world. In the meantime Barcelona welcomed these newcomers, especially Dali in his new exhibitions at the druis Gallery

NOTES As quoted in haim finkelstein art and writing 1927 1942 salvador vdali san sebastia letter this single eye, suddenly enlarged,encompasses a whole scene of the bottom and surface of an ocean in which all poetic suggestions navigate, and where all the plastic possibilities are stabilized page 30 finkelstein.

1926 31finkelstein) how ironic then that greenberg may well have thought dalis art putrescent in both their senses. Art as the art of looking finlel 321926 circa Honey is sweeter than blood 1927 apparatus and hand 1927 s Lorcas exhibit of drawings 1927

lorca acting dead and his head appearing dead in dalis work sweeter b a putrefied donkey buzzing with small minute hands representing the beginning of spring 'poem' Gaceta Literaria 1927 soft and hard paradigm 'the sewing needles plunge into small nickels soft and sweet' 'poem of small things L'Amic de les Arts' 1927 totally anarchic ambiance' pg 42 finkelstein

masson ernst tanguy lorca miro picasso arp poetic autonomy ... of the image and of the imagination. the putrefied ass 1928 catalogue note for an arp exhibition by breton 'that canaries never sing sop well as when placed in the bottom of an aquarium' Oui 1 pg45 fellatio fingering coprophilia anal penetration shitting wounds death killing putrefaction rotting decay fear of homosexuality yet homoerotic imaginings. Fratricide encephalic headless heedless masturbation perversion copulation incest etc molestation absent sex frustration freudian lacan letting go inhibitions hysteria yet letting go devices for letting go. Paranoid critical method not 'letting go' no automatism

excrement blood blood tubes vessels spurting droplets/arrows what is repugnant/yet at bottom, desirable murder/violence violation terror fear desire fright sensitivity anal sadistic/masochist domanatrix gala the 'back' that disdains him so he gets back at the backrejecting femininity- by sabotaging imagery; anal fingering and the like. Coded camoflaged and disguised hidden. Enlarged hands signifying masturbation 57 finkelstein erotic provocations / incongruent with their surroundings ie coded/hidden layered with other more exposed exposures/ explicit overt depravity disguising misogyny (even from himself) or deliberate to be seen in future another day = fascism. Counter pose bretons love of women deflected love for more sympathetic too-close-to-home bataille bataille thus much more affinity with dalki asthetic and disguises codes and deeper meanings. A hidden love for women empowered by hatred given dutch courage out of fear of direct approach in opening stages of sufferagette age dihide to hide a secret perversion by a revealed one hidden layers of meaning dialectics of the soft and hard hidden and overt perversions to 1928 arps morphology beautiful yet e arly in march 1929 script of en chien andalou with bunuel '' boats vulva vagina uterus womb breasts soft forms dali publishes article oui1 105 'review of anti-artistic tendencies' march 1929 reviews peret french poems

review of lorcas poetry patina-artificial antique- equals caca or shit waste products of the past fink 67 dalis 'poetry of the mass manufactured' march 1928 Arte Nouveuuae Collage Freud Bataille Breton Dali other critics art historians,. Date Barcelona prior. More beautiful before and after/ more complex characteristic method later seminal and canononical History of Dada Surrewalism New York Dada Paris dada Magazines Breton Barcelona why surrealism there? Barcelona characteristics Paris reasons for step-up? Pressure of artscene Breton bataille contesting.

Who Breton Philosophy?Who bataille. Philosophy Batailles illustration Barcelona pictures plus other 'significant' examples

Prior to Paris 1929 stock market crash. Not so complex imagery collage, freud etc surrealism

Dal became intensely interested in film when he was young, going to the theatre most Sundays. He was part of the era where silent films were being viewed and drawing on the medium of film became popular. He believed there were two dimensions to the theories of film and cinema: "things

themselves", the facts that are presented in the world of the camera; and "photographic imagination", the way the camera shows the picture and how creative or imaginative it looks.[67] Dal was active in front of and behind the scenes in the film world. He created pieces of artwork such as Destino, on which he collaborated with Walt Disney. He is also credited as co-creator of Luis Buuel's surrealist film Un Chien Andalou, a 17-minute French art film co-written with Luis Buuel that is widely remembered for its graphic opening scene simulating the slashing of a human eyeball with a razor. This film is what Dal is known for in the independent film world. Un Chien Andalou was Dal's way of creating his dreamlike qualities in the real world. Images would change and scenes would switch, leading the viewer in a completely different direction from the one they were previously viewing. The second film he produced with Buuel was entitled L'Age d'Or, and it was performed at Studio 28 in Paris in 1930. L'Age d'Or was "banned for years after fascist and anti-Semitic groups staged a stink bomb and inkthrowing riot in the Paris theater where it was shown."[68] Although negative aspects of society were being thrown into the life of Dal and obviously affecting the success of his artwork, it did not hold him back from expressing his own ideas and beliefs in his art. Both of these films, Un Chien Andalou and L'Age d'Or, have had a tremendous impact on the independent surrealist film movement. "If Un Chien Andalou stands as the supreme record of Surrealism's adventures into the realm of the unconscious, then L'ge d'Or is perhaps the most trenchant and implacable expression of its revolutionary intent."[69]

Dal also worked with other famous filmmakers, such as Alfred Hitchcock. The most well-known of his film projects is

probably the dream sequence in Hitchcock's Spellbound, which heavily delves into themes of psychoanalysis. Hitchcock needed a dreamlike quality to his film, which dealt with the idea that a repressed experience can directly trigger a neurosis, and he knew that Dal's work would help create the atmosphere he wanted in his film. He also worked on a documentary called Chaos and Creation, which has a lot of artistic references thrown into it to help one see what Dal's vision of art really is. He also worked on the Disney short film production Destino. Completed in 2003 by Baker Bloodworth and Roy E. Disney, it contains dreamlike images of strange figures flying and walking about. It is based on Mexican songwriter Armando Dominguez' song "Destino". When Disney hired Dal to help produce the film in 1946, they were not prepared for the work that lay ahead. For eight months, they continuously animated until their efforts had to come to a stop when they realized they were in financial trouble. They had no more money to finish the production of the animated film; however, it was eventually finished and shown in various film festivals. The film consists of Dal's artwork interacting with Disney's character animation. Dal completed only one other film in his lifetime, Impressions of Upper Mongolia (1975), in which he narrated a story about an expedition in search of giant hallucinogenic mushrooms. The imagery was based on microscopic uric acid stains on the brass band of a ballpoint pen on which Dal had been urinating for several weeks.[70]

PLAN

Proposal Essay

Phillip OSullivan

Writing Around The Lugubrious Game (1929) By Salvador Dali The Essay Proposal is to examine the Painting 'The Lugubrious Game' By Salvador Dali at the time of its exhibition in Paris. Responses to the Painting will be looked at, particularly as in the writings and from the various standpoints, of Andre Breton, Salvador Dali and Bataille. At least half to two thirds of the essay will cover these aspects. Secondarily the surrounding context of surrealism and Marxism (a little) and Psychology, as in the work of Sigmund Freud will be examined in the light of Salvador Dali's espoused 'paranoid critical-analytical method'. Batailles diagram will be examined as in this light. Thirdly the writer will briefly offer his own analysis of the picture, based on the above and on examining later artworks and views arising out of Salvador Dalis career and pictorial development in so much as it throws hindsight-insights back into our combined understanding of the picture. With the belief, that the plain dispute between Breton and Bataille, has left some oversights and gaps for interpretation, free of that conflict. There is no necessary art historical need to accept either Batailles or Bretons views as final and all conclusive. The Essay however will substantially leave the 'received' interpretations from these sources intact and only seeks to sketch an exploration of other possibilities. The principle contention will be the observation of an overall 'back view of a woman figure' for its overall schema, where the most 'exploded' umbrella-hatted oval shape above right comprises the 'head', which we see as if 'inside'. This being consistent with Dalis later exploding quantum pictures and with the many 'back views' of women we see in Dalis oeuvre. Some other secondary possible interpretations will also be detailed in regard to these inner features, particularly in regard to Freudian 'oral' understandings; accepting, any lack, or pretence of expert knowledge. However for the essay, rudimentary research into Freuds concept of the oral phase will be outlined. Plainly the painting includes erotic references and notes on fellatio, cunnilingus, 'phallic' and vaginal symbols, masturbation as well as castration fears and images; in fact, possibly the whole sexual peccadillo machinery. The introductions and conclusion of the essay will briefly insert the picture into an art

historical narrative covering both the artists career and that of other surrealists, and within the longer history of weird and perplexing images pertaining to the art canon. ................................................................................................. NOTES Coversheet. Writers Bataille Breton Dali Others secondary Pictorial analysis.Bataille Dali myself 300 words Reviewers- historical context concept psychology paranoia method. surrealism dada exhibition automatism imagination Avida dollars he was to become incipient then? Gathered up in the backwash of Hindsight... Other works like it more clearly in later oeuvre ie exploded quantum mechanics view and rear end view/face turning away so typical of his work. Image coded quadrants Batailles schema. Discussed. Gridded Overlooked areas Egg room Atlas anatomy cerebrum Adolf hitler dildo anal Methods of seeing hologram mentally generated hologram Duchamp large glass. Distorting images morph Holbein. Anamorphic images slanted Holbein Ascobobli ? Brueghal? Heronimous Bosch.Leonardo Ernst De Chirico Carra etc. Weird fantasy history. Aubrey Beardsley. 3d bifocal image/ double images so painted areas do double or triple visionary duty. Secret images hidden imagery trick on public... how he fooled the public flirting with fraud. Scatological/erotic imagery Phillip Trusttrum sideways photographs. Squinted seeing. Overlapped optically Reversed inverted perverted images rotated Pictorial criminal treachery. madness Title Dismal Sport Lugubrious Game Sport with the viewer/critic other artists/ manufactured in full psychological knowledge in the studio an artwork of tricks. Inserted between two critics. ..................................................................................................... 300 words 263/563 658/ 400 words. 1311words -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------BIBLIOGRAPHY General Sources Moorehouse, Paul. Dali 2001 PRC Publishing London Bradbury, Kirsten. Essential Dali DemseyParr 1999 Bath. Klingsohr-Leroy, Cathrin. Surrealism Taschen 2005 Romero, Luis. DALI Chartweil Books Seacaucus 1975 Ades, Dawn. Dali Thames & Hudson 1982 London Naret, Giles. Dali Taschen 2004 Los Angeles. PRIMARY Source Finkelstein Haim Salvador Dali's Art and Writings 1927-1942: The Metaphoses of Narcissus Cambridge University Press 1996 Plus texts in Reader.

Salvador Dal

This is a Catalan name. The first family name is Dal and the second is Domnech. Salvador Dal

Salvador Dal photographed by Carl Van Vechten on November 29, 1939 Birth name Salvador Domingo Felipe Jacinto Dal i Domnech (1904-05-11) Figueres, Catalonia, Spain Died January 23, 1989(1989-01-23) (aged 84) Figueres, Catalonia, Spain Nationality Spanish Field Painting, Drawing, Photography, Sculpture, Writing, Film Training San Fernando School of Fine Arts, Madrid Movement Cubism, Dada, Surrealism Works The Persistence of Memory (1931) Face of Mae West Which May Be Used as an Apartment, (1935) Soft Construction with Boiled Beans (Premonition of Civil War) (1936) Swans Reflecting Elephants (1937) Ballerina in a Death's Head (1939) Dream Caused by the Flight of a Bee Around a Pomegranate a Second Before Awakening (1944)

The Temptation of St. Anthony (1946) Galatea of the Spheres (1952) Crucifixion (Corpus Hypercubus) (1954)

Salvador Domnec Felip Jacint Dal i Domnech, Marquis de Pbol (May 11, 1904 January 23, 1989), commonly known as Salvador Dal (Catalan pronunciation: [so i]), was a prominent Spanish surrealist painter born in Figueres.

Dal was a skilled draftsman, best known for the striking and bizarre images in his surrealist work. His painterly skills are often attributed to the influence of Renaissance masters.[1] [2] His best-known work, The Persistence of Memory, was completed in 1931. Dal's expansive artistic repertoire includes film, sculpture, and photography, in collaboration with a range of artists in a variety of media.

Dal attributed his "love of everything that is gilded and excessive, my passion for luxury and my love of oriental clothes"[3] to a self-styled "Arab lineage," claiming that his ancestors were descended from the Moors.

Dal was highly imaginative, and also had an affinity for partaking in unusual and grandiose behavior. His eccentric manner and attention-grabbing public actions sometimes drew more attention than his artwork to the dismay of those who held his work in high esteem and to the irritation of his critics.[4]

Contents 1 Biography 1.1 Early life 1.2 Madrid and Paris 1.3 1929 through World War II 1.4 Later years in Catalonia 2 Symbolism 3 Endeavors outside painting 4 Politics and personality 5 Legacy 6 Listing of selected works 6.1 Novels 7 Gallery 8 See also 9 Notes 10 References 11 External links

[edit] Biography [edit] Early life

Salvador Domingo Felipe Jacinto Dal i Domnech was born on May 11, 1904 at 8:45 am GMT[5] in the town of Figueres, in the Empord region, close to the French border in Catalonia, Spain.[6] Dal's older brother, also named Salvador (born October 12, 1901), had died of gastroenteritis nine months earlier, on August 1, 1903. His father, Salvador Dal i Cus, was a middle-class lawyer and notary[7] whose strict disciplinary approach was tempered by his wife, Felipa Domenech Ferrs, who encouraged her son's artistic endeavors.[8] When he was five, Dal was taken to his brother's grave and told by his parents that he was his brother's reincarnation,[9] a concept which he came to believe.[10] Of his brother, Dal said, "...[we] resembled each other like two drops of water, but we had different reflections."[11] He "was probably a first version of myself but conceived too much in the absolute."[11]

Dal also had a sister, Ana Mara, who was three years younger.[7] In 1949, she published a book about her brother, Dal As Seen By His Sister.[12] His childhood friends included future FC Barcelona footballers Sagibarba and Josep Samitier. During holidays at the Catalan resort of Cadaqus, the trio played football together.

Dal attended drawing school. In 1916, Dal also discovered modern painting on a summer vacation trip to Cadaqus with the family of Ramon Pichot, a local artist who made regular trips to Paris.[7] The next year, Dal's father organized an exhibition of his charcoal drawings in their family home. He had his first public exhibition at the Municipal Theater in Figueres in 1919.

In February 1921, Dal's mother died of breast cancer. Dal was sixteen years old; he later said his mother's death "was the greatest blow I had experienced in my life. I worshipped her... I could not resign myself to the loss of a being on whom I counted to make invisible the unavoidable blemishes of my soul."[13] After her death, Dal's father married his deceased wife's sister. Dal did not resent this marriage, because he had a great love and respect for his aunt.[7]

[edit] Madrid and Paris

Wild-eyed antics of Dal (left) and fellow surrealist artist Man Ray in Paris on June 16, 1934, photographed by Carl Van Vechten.In 1922, Dal moved into the Residencia de Estudiantes (Students' Residence) in Madrid[7] and studied at the Academia de San Fernando (School of Fine Arts). A lean 1.72 m (5 ft. 7 in.) tall,[14] Dal already drew attention as an eccentric and dandy man. He wore long hair and sideburns, coat, stockings, and knee breeches in the style of English aesthetes of the late 19th century.

At the Residencia, he became close friends with (among others) Pepn Bello, Luis Buuel, and Federico Garca Lorca. The friendship with Lorca had a strong element of mutual passion,[15] but Dal rejected the poet's sexual advances. [16]

However, it was his paintings, in which he experimented with Cubism, that earned him the most attention from his fellow students. At the time of these early works, Dal probably did not completely understand the Cubist movement. His only information on Cubist art came from magazine articles and a catalog given to him by Pichot, since there were no Cubist artists in Madrid at the time. In 1924, the still-unknown Salvador Dal illustrated a book for the first time. It was a publication of the Catalan poem "Les bruixes de Llers" ("The Witches of Llers") by his friend and schoolmate, poet Carles Fages de Climent. Dal also experimented with Dada, which influenced his work throughout his life.

Dal was expelled from the Academia in 1926, shortly before his final exams, when he stated that no one on the faculty was competent enough to examine him.[17] His mastery of painting skills was evidenced by his realistic Basket of Bread, painted in 1926.[18] That same year, he made his first visit to Paris, where he met Pablo Picasso, whom the young Dal revered. Picasso had already heard favorable reports about Dal from Joan Mir. As he developed his own style over the next few years, Dal made a number of works heavily influenced by Picasso and Mir.

Some trends in Dal's work that would continue throughout his life were already evident in the 1920s. Dal devoured influences from many styles of art, ranging from the most academically classic to the most cutting-edge avant garde. [19] His classical influences included Raphael, Bronzino, Francisco de Zurbaran, Vermeer, and Velzquez.[20] He used both classical and modernist techniques, sometimes in separate works, and sometimes combined. Exhibitions of his

works in Barcelona attracted much attention along with mixtures of praise and puzzled debate from critics.

Dal grew a flamboyant moustache, influenced by seventeenth-century Spanish master painter Diego Velzquez. The moustache became an iconic trademark of his appearance for the rest of his life.

[edit] 1929 through World War II In 1929, Dal collaborated with surrealist film director Luis Buuel on the short film Un Chien Andalou (An Andalusian Dog). His main contribution was to help Buuel write the script for the film. Dal later claimed to have also played a significant role in the filming of the project, but this is not substantiated by contemporary accounts.[21] Also, in August 1929, Dal met his muse, inspiration, and future wife Gala, [22] born Elena Ivanovna Diakonova. She was a Russian immigrant ten years his senior, who at that time was married to surrealist poet Paul luard. In the same year, Dal had important professional exhibitions and officially joined the Surrealist group in the Montparnasse quarter of Paris. His work had already been heavily influenced by surrealism for two years. The Surrealists hailed what Dal called the paranoiac-critical method of accessing the subconscious for greater artistic creativity.[7][8]

Meanwhile, Dal's relationship with his father was close to rupture. Don Salvador Dal y Cusi strongly disapproved of his son's romance with Gala, and saw his connection to the Surrealists as a bad influence on his morals. The last straw was when Don Salvador read in a Barcelona newspaper that

his son had recently exhibited in Paris a drawing of the "Sacred Heart of Jesus Christ", with a provocative inscription: "Sometimes, I spit for fun on my mother's portrait."[23]

Outraged, Don Salvador demanded that his son recant publicly. Dal refused, perhaps out of fear of expulsion from the Surrealist group, and was violently thrown out of his paternal home on December 28, 1929. His father told him that he would disinherit him, and that he should never set foot in Cadaqus again. The following summer, Dal and Gala rented a small fisherman's cabin in a nearby bay at Port Lligat. He bought the place, and over the years enlarged it, gradually building his much beloved villa by the sea.

The Persistence of MemoryIn 1931, Dal painted one of his most famous works, The Persistence of Memory,[24] which introduced a surrealistic image of soft, melting pocket watches. The general interpretation of the work is that the soft watches are a rejection of the assumption that time is rigid or deterministic. This idea is supported by other images in the work, such as the wide expanding landscape, and the other limp watches, shown being devoured by ants.[25]

Dal and Gala, having lived together since 1929, were married in 1934 in a civil ceremony. They later remarried in a Catholic ceremony in 1958.

Dal was introduced to America by art dealer Julian Levy in 1934. The exhibition in New York of Dal's works, including Persistence of Memory, created an immediate sensation. Social Register listees feted him at a specially organized "Dal Ball." He showed up wearing a glass case on his chest, which contained a brassiere.[26] In that year, Dal and Gala also attended a masquerade party in New York, hosted for them by heiress Caresse Crosby. For their costumes, they dressed as the Lindbergh baby and his kidnapper. The resulting uproar in the press was so great that Dal apologized. When he returned to Paris, the Surrealists confronted him about his apology for a surrealist act.[27]

While the majority of the Surrealist artists had become increasingly associated with leftist politics, Dal maintained an ambiguous position on the subject of the proper relationship between politics and art. Leading surrealist Andr Breton accused Dal of defending the "new" and "irrational" in "the Hitler phenomenon," but Dal quickly rejected this claim, saying, "I am Hitlerian neither in fact nor intention."[28] Dal insisted that surrealism could exist in an apolitical context and refused to explicitly denounce fascism. [citation needed] Among other factors, this had landed him in trouble with his colleagues. Later in 1934, Dal was subjected to a "trial", in which he was formally expelled from the Surrealist group.[22] To this, Dal retorted, "I myself am surrealism."[17]

In 1936, Dal took part in the London International Surrealist Exhibition. His lecture, entitled Fantomes paranoiaques authentiques, was delivered while wearing a deep-sea diving suit and helmet.[29] He had arrived carrying a billiard cue

and leading a pair of Russian wolfhounds, and had to have the helmet unscrewed as he gasped for breath. He commented that "I just wanted to show that I was 'plunging deeply' into the human mind."[30]

Also in 1936, at the premiere screening of Joseph Cornell's film Rose Hobart at Julian Levy's gallery in New York City, Dal became famous for another incident. Levy's program of short surrealist films was timed to take place at the same time as the first surrealism exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, featuring Dal's work. Dal was in the audience at the screening, but halfway through the film, he knocked over the projector in a rage. My idea for a film is exactly that, and I was going to propose it to someone who would pay to have it made, he said. "I never wrote it down or told anyone, but it is as if he had stolen it." Other versions of Dal's accusation tend to the more poetic: "He stole it from my subconscious!" or even "He stole my dreams!"[31]

At this stage, Dal's main patron in London was the very wealthy Edward James. He had helped Dal emerge into the art world by purchasing many works and by supporting him financially for two years. They also collaborated on two of the most enduring icons of the Surrealist movement: the Lobster Telephone and the Mae West Lips Sofa.[citation needed]

In 1938, Dal met Sigmund Freud thanks to Stefan Zweig. Later, in September 1938, Salvador Dal was invited by Gabrielle Coco Chanel to her house La Pausa in Roquebrune on the French Riviera. There he painted numerous paintings

he later exhibited at Julien Levy Gallery in New York.[32][33] La Pausa has been partially replicated at the Dallas Museum of Art to welcome the Reves collection and part of Chanel's original furniture for the house.[34]

In 1939, Breton coined the derogatory nickname "Avida Dollars", an anagram for Salvador Dal, and a phonetic rendering of the French avide dollars, which may be translated as "eager for dollars".[35] This was a derisive reference to the increasing commercialization of Dal's work, and the perception that Dal sought self-aggrandizement through fame and fortune. Some surrealists henceforth spoke of Dal in the past tense, as if he were dead.[citation needed] The Surrealist movement and various members thereof (such as Ted Joans) would continue to issue extremely harsh polemics against Dal until the time of his death and beyond.

In 1940, as World War II was in full swing at Europe, Dal and Gala moved to the United States, where they lived for eight years. After the move, Dal returned to the practice of Catholicism. "During this period, Dal never stopped writing," wrote Robert and Nicolas Descharnes.[36]

In 1941, Dal drafted a film scenario for Jean Gabin called Moontide. In 1942, he published his autobiography, The Secret Life of Salvador Dal. He wrote catalogs for his exhibitions, such as that at the Knoedler Gallery in New York in 1943. Therein he expounded, "Surrealism will at least have served to give experimental proof that total sterility and attempts at automatizations have gone too far and have

led to a totalitarian system. ... Today's laziness and the total lack of technique have reached their paroxysm in the psychological signification of the current use of the college." He also wrote a novel, published in 1944, about a fashion salon for automobiles. This resulted in a drawing by Edwin Cox in The Miami Herald, depicting Dal dressing an automobile in an evening gown.[36] Also in The Secret Life, Dal suggested that he had split with Buuel because the latter was a Communist and an atheist. Buuel was fired (or resigned) from MOMA, supposedly after Cardinal Spellman of New York went to see Iris Barry, head of the film department at MOMA. Buuel then went back to Hollywood where he worked in the dubbing department of Warner Bros. from 1942 to 1946. In his 1982 autobiography Mon Dernier soupir (English translation My Last Sigh published 1983), Buuel wrote that, over the years, he rejected Dal's attempts at reconciliation.[37]

An Italian friar, Gabriele Maria Berardi, claimed to have performed an exorcism on Dal while he was in France in 1947.[38] In 2005, a sculpture of Christ on the Cross was discovered in the friar's estate. It had been claimed that Dal gave this work to his exorcist out of gratitude,[38] and two Spanish art experts confirmed that there were adequate stylistic reasons to believe the sculpture was made by Dal. [38]

[edit] Later years in Catalonia Starting in 1949, Dal spent his remaining years back in his beloved Catalonia. The fact that he chose to live in Spain while it was ruled by Franco drew criticism from progressives and from many other artists.[39] As such, it is probable that

the common dismissal of Dal's later works by some Surrealists and art critics was related partially to politics rather than to the artistic merit of the works themselves. In 1959, Andr Breton organized an exhibit called Homage to Surrealism, celebrating the fortieth anniversary of Surrealism, which contained works by Dal, Joan Mir, Enrique Tbara, and Eugenio Granell. Breton vehemently fought against the inclusion of Dal's Sistine Madonna in the International Surrealism Exhibition in New York the following year.[40]

Late in his career, Dal did not confine himself to painting, but experimented with many unusual or novel media and processes: he made bulletist works[41] and was among the first artists to employ holography in an artistic manner.[42] Several of his works incorporate optical illusions. In his later years, young artists such as Andy Warhol proclaimed Dal an important influence on pop art.[43] Dal also had a keen interest in natural science and mathematics. This is manifested in several of his paintings, notably in the 1950s, in which he painted his subjects as composed of rhinoceros horns. According to Dal, the rhinoceros horn signifies divine geometry because it grows in a logarithmic spiral. He also linked the rhinoceros to themes of chastity and to the Virgin Mary.[44] Dal was also fascinated by DNA and the hypercube (a 4-dimensional cube); an unfolding of a hypercube is featured in the painting Crucifixion (Corpus Hypercubus).

Dal's postWorld War II period bore the hallmarks of technical virtuosity and an interest in optical illusions, science, and religion. He became an increasingly devout

Catholic, while at the same time he had been inspired by the shock of Hiroshima and the dawning of the "atomic age". Therefore Dal labeled this period "Nuclear Mysticism." In paintings such as "The Madonna of Port-Lligat" (first version) (1949) and "Corpus Hypercubus" (1954), Dal sought to synthesize Christian iconography with images of material disintegration inspired by nuclear physics.[45] "Nuclear Mysticism" included such notable pieces as La Gare de Perpignan (1965) and The Hallucinogenic Toreador (1968 70). In 1960, Dal began work on the Dal Theatre and Museum in his home town of Figueres; it was his largest single project and the main focus of his energy through 1974. He continued to make additions through the mid1980s.[citation needed]

In 1968, Dal filmed a humorous television advertisement for Lanvin chocolates.[46] In this, he proclaims in French "Je suis fou de chocolat Lanvin!" (I'm crazy about Lanvin chocolate) while biting a morsel causing him to become crosseyed and his moustache to swivel upwards. In 1969, he designed the Chupa Chups logo in addition to facilitating the design of the advertising campaign for the 1969 Eurovision Song Contest and creating a large on-stage metal sculpture that stood at the Teatro Real in Madrid.

Dal in 1972.In the television programme Dirty Dal: A Private View broadcast on Channel 4 on June 3, 2007, art critic Brian Sewell described his acquaintance with Dal in the late 1960s, which included lying down in the fetal position

without trousers in the armpit of a figure of Christ and masturbating for Dal, who pretended to take photos while fumbling in his own trousers.[47][48]

In 1980, Dal's health took a catastrophic turn. His nearsenile wife, Gala, allegedly had been dosing him with a dangerous cocktail of unprescribed medicine that damaged his nervous system, thus causing an untimely end to his artistic capacity. At 76 years old, Dal was a wreck, and his right hand trembled terribly, with Parkinson-like symptoms. [49]

In 1982, King Juan Carlos bestowed on Dal the title of Marqus de Dal de Pbol[50][51] (English: Marquis of Dal de Pbol) in the nobility of Spain, hereby referring to Pbol, the place where he lived. The title was in first instance hereditary, but on request of Dal changed for life only in 1983.[50] To show his gratitude for this, Dal later gave the king a drawing (Head of Europa, which would turn out to be Dal's final drawing) after the king visited him on his deathbed.

Sant Pere in Figueres, scene of Dal's Baptism, First Communion, and funeral

Dal Theatre and Museum in Figueres, where he is also buried

Dal's crypt at the Dal Theatre and Museum in Figueres, stating his titlesGala died on June 10, 1982. After Gala's death, Dal lost much of his will to live. He deliberately dehydrated himself, possibly as a suicide attempt, or perhaps in an attempt to put himself into a state of suspended animation as he had read that some microorganisms could do. He moved from Figueres to the castle in Pbol, which he had bought for Gala and was the site of her death. In 1984, a fire broke out in his bedroom[52] under unclear circumstances. It was possibly a suicide attempt by Dal, or possibly simple negligence by his staff.[17] In any case, Dal was rescued and returned to Figueres, where a group of his friends, patrons, and fellow artists saw to it that he was comfortable living in his TheaterMuseum in his final years.

There have been allegations that Dal was forced by his guardians to sign blank canvases that would later, even after his death, be used in forgeries and sold as originals.[53] As a result, art dealers tend to be wary of late works attributed to Dal.[citation needed]

In November 1988, Dal entered the hospital with heart failure, and on December 5, 1988 was visited by King Juan Carlos, who confessed that he had always been a serious devotee of Dal.[54]

On January 23, 1989, while his favorite record of Tristan and Isolde played, he died of heart failure at Figueres at the age of 84, and, coming full circle, is buried in the crypt of his

Teatro Museo in Figueres. The location is across the street from the church of Sant Pere, where he had his baptism, first communion, and funeral, and is three blocks from the house where he was born.[55]

The Gala-Salvador Dal Foundation currently serves as his official estate.[56] The U.S. copyright representative for the Gala-Salvador Dal Foundation is the Artists Rights Society. [57] In 2002, the Society made the news when they asked Google to remove a customized version of its logo put up to commemorate Dal, alleging that portions of specific artworks under their protection had been used without permission. Google complied with the request, but denied that there was any copyright violation.[citation needed]

[edit] Symbolism Dal employed extensive symbolism in his work. For instance, the hallmark "soft watches" that first appear in The Persistence of Memory suggest Einstein's theory that time is relative and not fixed.[25] The idea for clocks functioning symbolically in this way came to Dal when he was staring at a runny piece of Camembert cheese on a hot day in August. [58]

The elephant is also a recurring image in Dal's works. It first appeared in his 1944 work Dream Caused by the Flight of a Bee Around a Pomegranate a Second Before Awakening. The elephants, inspired by Gian Lorenzo Bernini's sculpture base in Rome of an elephant carrying an ancient obelisk,[59] are portrayed "with long, multijointed, almost invisible legs of desire"[60] along with obelisks on their backs. Coupled with

the image of their brittle legs, these encumbrances, noted for their phallic overtones, create a sense of phantom reality. "The elephant is a distortion in space," one analysis explains, "its spindly legs contrasting the idea of weightlessness with structure."[60] "I am painting pictures which make me die for joy, I am creating with an absolute naturalness, without the slightest aesthetic concern, I am making things that inspire me with a profound emotion and I am trying to paint them honestly." Salvador Dal, in Dawn Ades, Dal and Surrealism.

The egg is another common Dalesque image. He connects the egg to the prenatal and intrauterine, thus using it to symbolize hope and love;[61] it appears in The Great Masturbator and The Metamorphosis of Narcissus. The Metamorphosis of Narcissus also symbolized death and petrification. Various animals appear throughout his work as well: ants point to death, decay, and immense sexual desire; the snail is connected to the human head (he saw a snail on a bicycle outside Freud's house when he first met Sigmund Freud); and locusts are a symbol of waste and fear.[61]

[edit] Endeavors outside painting

The Dali Atomicus, photo by Philippe Halsman (1948), shown before its supporting wires were removed.Dal was a versatile artist. Some of his more popular works are sculptures and other objects, and he is also noted for his contributions to theatre, fashion, and photography, among other areas.

Two of the most popular objects of the surrealist movement were Lobster Telephone and Mae West Lips Sofa, completed by Dal in 1936 and 1937, respectively. Surrealist artist and patron Edward James commissioned both of these pieces from Dal; James inherited a large English estate in West Dean, West Sussex when he was five and was one of the foremost supporters of the surrealists in the 1930s.[62] "Lobsters and telephones had strong sexual connotations for [Dal]," according to the display caption for the Lobster Telephone at the Tate Gallery, "and he drew a close analogy between food and sex."[63] The telephone was functional, and James purchased four of them from Dal to replace the phones in his retreat home. One now appears at the Tate Gallery; the second can be found at the German Telephone Museum in Frankfurt; the third belongs to the Edward James Foundation; and the fourth is at the National Gallery of Australia.[62]

The wood and satin Mae West Lips Sofa was shaped after the lips of actress Mae West, whom Dal apparently found fascinating.[22] West was previously the subject of Dal's 1935 painting The Face of Mae West. Mae West Lips Sofa currently resides at the Brighton and Hove Museum in England.

Between 1941 and 1970, Dal created an ensemble of 39 jewels. The jewels are intricate, and some contain moving parts. The most famous jewel, "The Royal Heart", is made of gold and is encrusted with 46 rubies, 42 diamonds, and four emeralds and is created in such a way that the center "beats" much like a real heart. Dal himself commented that

"Without an audience, without the presence of spectators, these jewels would not fulfill the function for which they came into being. The viewer, then, is the ultimate artist." (Dal, 1959.) The "Dal Joies" ("The Jewels of Dal") collection can be seen at the Dal Theater Museum in Figueres, Catalonia, Spain, where it is on permanent exhibition.

In theatre, Dal constructed the scenery for Federico Garca Lorca's 1927 romantic play Mariana Pineda.[64] For Bacchanale (1939), a ballet based on and set to the music of Richard Wagner's 1845 opera Tannhuser, Dal provided both the set design and the libretto.[65] Bacchanale was followed by set designs for Labyrinth in 1941 and The ThreeCornered Hat in 1949.[66]

Dal became intensely interested in film when he was young, going to the theatre most Sundays. He was part of the era where silent films were being viewed and drawing on the medium of film became popular. He believed there were two dimensions to the theories of film and cinema: "things themselves", the facts that are presented in the world of the camera; and "photographic imagination", the way the camera shows the picture and how creative or imaginative it looks.[67] Dal was active in front of and behind the scenes in the film world. He created pieces of artwork such as Destino, on which he collaborated with Walt Disney. He is also credited as co-creator of Luis Buuel's surrealist film Un Chien Andalou, a 17-minute French art film co-written with Luis Buuel that is widely remembered for its graphic opening scene simulating the slashing of a human eyeball with a razor. This film is what Dal is known for in the

independent film world. Un Chien Andalou was Dal's way of creating his dreamlike qualities in the real world. Images would change and scenes would switch, leading the viewer in a completely different direction from the one they were previously viewing. The second film he produced with Buuel was entitled L'Age d'Or, and it was performed at Studio 28 in Paris in 1930. L'Age d'Or was "banned for years after fascist and anti-Semitic groups staged a stink bomb and inkthrowing riot in the Paris theater where it was shown."[68] Although negative aspects of society were being thrown into the life of Dal and obviously affecting the success of his artwork, it did not hold him back from expressing his own ideas and beliefs in his art. Both of these films, Un Chien Andalou and L'Age d'Or, have had a tremendous impact on the independent surrealist film movement. "If Un Chien Andalou stands as the supreme record of Surrealism's adventures into the realm of the unconscious, then L'ge d'Or is perhaps the most trenchant and implacable expression of its revolutionary intent."[69]

Dal also worked with other famous filmmakers, such as Alfred Hitchcock. The most well-known of his film projects is probably the dream sequence in Hitchcock's Spellbound, which heavily delves into themes of psychoanalysis. Hitchcock needed a dreamlike quality to his film, which dealt with the idea that a repressed experience can directly trigger a neurosis, and he knew that Dal's work would help create the atmosphere he wanted in his film. He also worked on a documentary called Chaos and Creation, which has a lot of artistic references thrown into it to help one see what Dal's vision of art really is. He also worked on the Disney short film production Destino. Completed in 2003 by Baker Bloodworth and Roy E. Disney, it contains dreamlike images

of strange figures flying and walking about. It is based on Mexican songwriter Armando Dominguez' song "Destino". When Disney hired Dal to help produce the film in 1946, they were not prepared for the work that lay ahead. For eight months, they continuously animated until their efforts had to come to a stop when they realized they were in financial trouble. They had no more money to finish the production of the animated film; however, it was eventually finished and shown in various film festivals. The film consists of Dal's artwork interacting with Disney's character animation. Dal completed only one other film in his lifetime, Impressions of Upper Mongolia (1975), in which he narrated a story about an expedition in search of giant hallucinogenic mushrooms. The imagery was based on microscopic uric acid stains on the brass band of a ballpoint pen on which Dal had been urinating for several weeks.[70]

Dal built a repertoire in the fashion and photography industries as well. In fashion, his cooperation with Italian fashion designer Elsa Schiaparelli is well-known, where Dal was hired by Schiaparelli to produce a white dress with a lobster print. Other designs Dal made for her include a shoeshaped hat and a pink belt with lips for a buckle. He was also involved in creating textile designs and perfume bottles. In 1950, Dal created a special "costume for the year 2045" with Christian Dior.[65] Photographers with whom he collaborated include Man Ray, Brassa, Cecil Beaton, and Philippe Halsman.

With Man Ray and Brassa, Dal photographed nature; with the others, he explored a range of obscure topics, including (with Halsman) the Dal Atomica series (1948)inspired by

his painting Leda Atomica which in one photograph depicts "a painter's easel, three cats, a bucket of water, and Dal himself floating in the air."[65]

References to Dal in the context of science are made in terms of his fascination with the paradigm shift that accompanied the birth of quantum mechanics in the twentieth century. Inspired by Werner Heisenberg's Uncertainty Principle, in 1958 he wrote in his "Anti-Matter Manifesto": "In the Surrealist period, I wanted to create the iconography of the interior world and the world of the marvelous, of my father Freud. Today, the exterior world and that of physics has transcended the one of psychology. My father today is Dr. Heisenberg."[71]

In this respect, The Disintegration of the Persistence of Memory, which appeared in 1954, in hearkening back to The Persistence of Memory, and in portraying that painting in fragmentation and disintegration summarizes Dal's acknowledgment of the new science.[71]

Architectural achievements include his Port Lligat house near Cadaqus, as well as the Dream of Venus surrealist pavilion at the 1939 World's Fair, which contained within it a number of unusual sculptures and statues. His literary works include The Secret Life of Salvador Dal (1942), Diary of a Genius (195263), and Oui: The Paranoid-Critical Revolution (1927 33). The artist worked extensively in the graphic arts, producing many etchings and lithographs. While his early work in printmaking is equal in quality to his important paintings as he grew older, he would sell the rights to

images but not be involved in the print production itself. In addition, a large number of unauthorized fakes were produced in the eighties and nineties, thus further confusing the Dal print market. He took a stab at industrial design in the 1970s with a 500-piece run of the upscale Suomi tableware by Timo Sarpaneva that Dal decorated for the German Rosenthal porcelain maker's Studio Linie.[72]

One of Dal's most unorthodox artistic creations may have been an entire person. At a French nightclub in 1965, Dal met Amanda Lear, a fashion model then known as Peki D'Oslo.[73] Lear became his protg and muse,[73] writing about their affair in the authorized biography My Life With Dal (1986).[74] Transfixed by the mannish, larger-than-life Lear, Dal masterminded her successful transition from modeling to the music world, advising her on selfpresentation and helping spin mysterious stories about her origin as she took the disco-art scene by storm. According to Lear, she and Dal were united in a "spiritual marriage" on a deserted mountaintop.[73] Referred to as Dal's "Frankenstein,"[75] some believe Lear's name is a pun on the French "L'Amant Dal," or Lover of Dal. Lear took the place of an earlier muse, Ultra Violet (Isabelle Collin Dufresne), who had left Dal's side to join The Factory of Andy Warhol.[76]

An avid cheese maker, Dali would sometimes engross himself in cheese-making for over 4 months at a time. His favorite cheese was swiss.[citation needed]

[edit] Politics and personality

Dal in the 1960s wearing the flamboyant mustache style he popularized.Salvador Dal's politics played a significant role in his emergence as an artist. In his youth, he embraced both anarchism and communism, though his writings account anecdotes of making radical political statements more to shock listeners than from any deep conviction. This was in keeping with Dal's allegiance to the Dada movement.

As he grew older his political allegiances changed, especially as the Surrealist movement went through transformations under the leadership of Trotskyist Andr Breton, who is said to have called Dal in for questioning on his politics. In his 1970 book Dal by Dal, Dal was declaring himself an anarchist and monarchist.

With the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, Dal fled from fighting and refused to align himself with any group. Likewise, after World War II, George Orwell criticized Dal for "scuttling off like a rat as soon as France is in danger" after Dal prospered there for years: "When the European War approaches he has one preoccupation only: how to find a place which has good cookery and from which he can make a quick bolt if danger comes too near." In a notable 1944 review of Dal's autobiography, Orwell wrote, "One ought to be able to hold in one's head simultaneously the two facts that Dal is a good draughtsman and a disgusting human being."[77]

After his return to Catalonia after World War II, Dal became closer to the authoritarian Franco regime. Some of Dal's statements supported the Franco regime, congratulating Franco for his actions aimed "at clearing Spain of destructive forces."[39] Dal, having returned to the Catholic faith and becoming increasingly religious as time went on, may have been referring to the Republican atrocities during the Spanish Civil War.[78][79] Dal sent telegrams to Franco, praising him for signing death warrants for prisoners.[39] He even met Franco personally[80] and painted a portrait of Franco's granddaughter.

He also once sent a telegram praising the Conductor, Romanian Communist leader Nicolae Ceauescu, for his adoption of a scepter as part of his regalia. The Romanian daily newspaper Scnteia published it, without suspecting its mocking aspect. One of Dal's few possible bits of open disobedience was his continued praise of Federico Garca Lorca even in the years when Lorca's works were banned. [not in citation given][16]

Dal, a colorful and imposing presence in his ever-present long cape, walking stick, haughty expression, and upturned waxed mustache, was famous for having said that "every morning upon awakening, I experience a supreme pleasure: that of being Salvador Dal."[81] The entertainer Cher and her husband Sonny Bono, when young, came to a party at Dal's expensive residence in New York's Plaza Hotel and were startled when Cher sat down on an oddly shaped sexual vibrator left in an easy chair. When signing autographs for fans, Dal would always keep their pens. When interviewed by Mike Wallace on his 60 Minutes

television show, Dal kept referring to himself in the third person, and told the startled Mr. Wallace matter-of-factly that "Dal is immortal and will not die." During another television appearance, on The Tonight Show, Dal carried with him a leather rhinoceros and refused to sit upon anything else.[citation needed]

[edit] Legacy Salvador Dal has been cited as major inspiration from many modern artists, such as Damien Hirst, Noel Fielding, Jeff Koons and most other modern surrealists. Salvador Dali's manic expression and famous moustache have made him something of a Cult icon for the bizarre & surreal.

[edit] Listing of selected works Main article: List of works by Salvador Dal

The Philadelphia Museum of Art used a surreal entrance display including its steps, for the 2005 Salvador Dal exhibitionDal produced over 1,500 paintings in his career[82] in addition to producing illustrations for books, lithographs, designs for theatre sets and costumes, a great number of drawings, dozens of sculptures, and various other projects, including an animated short film for Disney. He also

collaborated with director Jack Bond in 1965, creating a movie titled Dal in New York. Below is a chronological sample of important and representative work, as well as some notes on what Dal did in particular years.[2]

In Carlos Lozano's biography, Sex, Surrealism, Dal, and Me, produced with the collaboration of Clifford Thurlow, Lozano makes it clear that Dal never stopped being a surrealist. As Dal said of himself: "the only difference between me and the surrealists is that I am a surrealist."[35]

1910 Landscape Near Figueras 1913 Vilabertin 1916 Fiesta in Figueras (begun 1914) 1917 View of Cadaqus with Shadow of Mount Pani 1918 Crepuscular Old Man (begun 1917) 1919 Port of Cadaqus (Night) (begun 1918) and Selfportrait in the Studio 1920 The Artist's Father at Llane Beach and View of Portdogu (Port Aluger) 1921 The Garden of Llaner (Cadaqus) (begun 1920) and Self-portrait 1922 Cabaret Scene and Night Walking Dreams 1923 Self Portrait with L'Humanite and Cubist Self Portrait with La Publicitat 1924 Still Life (Syphon and Bottle of Rum) (for Garca Lorca) and Portrait of Luis Buuel

1925 Large Harlequin and Small Bottle of Rum and a series of fine portraits of his sister Anna Maria, most notably Figure at a Window 1926 The Basket of Bread and Girl from Figueres 1927 Composition with Three Figures (Neo-Cubist Academy) and Honey is Sweeter than Blood (his first important surrealist work) 1929 Un Chien Andalou (An Andalusian Dog) film in collaboration with Luis Buuel, The Lugubrious Game, The Great Masturbator, The First Days of Spring, and The Profanation of the Host 1930 L'Age d'Or (The Golden Age) film in collaboration with Luis Buuel 1931 The Persistence of Memory (his most famous work, featuring the "melting clocks"), The Old Age of William Tell, and William Tell and Gradiva 1932 The Spectre of Sex Appeal, The Birth of Liquid Desires, Anthropomorphic Bread, and Fried Eggs on the Plate without the Plate. The Invisible Man (begun 1929) completed (although not to Dal's own satisfaction) 1933 Retrospective Bust of a Woman (mixed media sculpture collage) and Portrait of Gala With Two Lamb Chops Balanced on Her Shoulder, Gala in the Window 1934 The Ghost of Vermeer of Delft Which Can Be Used As a Table and A Sense of Speed 1935 Archaeological Reminiscence of Millet's Angelus and The Face of Mae West 1936 Autumn Cannibalism, Lobster Telephone, Soft Construction with Boiled Beans (Premonition of Civil War)

and two works titled Morphological Echo (the first of which began in 1934) 1937 Metamorphosis of Narcissus, Swans Reflecting Elephants, The Burning Giraffe, Sleep, The Enigma of Hitler, Mae West Lips Sofa and Cannibalism in Autumn 1938 The Sublime Moment and Apparition of Face and Fruit Dish on a Beach 1939 Shirley Temple, The Youngest, Most Sacred Monster of the Cinema in Her Time 1940 Slave Market with the Disappearing Bust of Voltaire, The Face of War 1941 Honey is Sweeter than Blood 1943 The Poetry of America and Geopoliticus Child Watching the Birth of the New Man 1944 Galarina and Dream Caused by the Flight of a Bee around a Pomegranate a Second Before Awakening 194448 Hidden Faces, a novel 1945, Basket of BreadRather Death than Shame and Fountain of Milk Flowing Uselessly on Three Shoes; also this year, Dal collaborated with Alfred Hitchcock on a dream sequence to the film Spellbound, to mutual dissatisfaction 1946 The Temptation of St. Anthony 1948 Les Elephants 1949 Leda Atomica and The Madonna of Port Lligat. Dal returned to Catalonia this year 1951 Christ of Saint John of the Cross and Exploding Raphaelesque Head

1951 Katharine Cornell, a portrait of the famed actress 1952 Galatea of the Spheres 1954 The Disintegration of the Persistence of Memory (begun in 1952), Crucifixion (Corpus Hypercubus) and Young Virgin Auto-Sodomized by the Horns of Her Own Chastity 1955 The Sacrament of the Last Supper, Lonesome Echo, record album cover for Jackie Gleason 1956 Still Life Moving Fast, Rinoceronte vestido con puntillas 1957 Santiago el Grande oil on canvas on permanent display at Beaverbrook Art Gallery in Fredericton, NB, Canada 1958 The Meditative Rose 1959 The Discovery of America by Christopher Columbus 1960 Composicin Numrica (de fond prparatoire inachev) 1960 Dal began work on the Teatro-Museo Gala Salvador Dal and Portrait of Juan de Pareja, the Assistant to Velzquez 19631964 They Will All Come from Saba a work in water color depicting the Magi at St. Petersbur's Dali Museum 1965 Dal donates a gouache, ink and pencil drawing of the Crucifixion to the Rikers Island jail in New York City. The drawing hung in the inmate dining room from 1965 to 1981[83] 1965 Dal in New York 1967 Tuna Fishing

1969 Chupa Chups logo 1969 Improvisation on a Sunday Afternoon, television collaboration with the rock group Nirvana 1970 The Hallucinogenic Toreador, acquired in 1969 by A. Reynolds Morse & Eleanor R. Morse before it was completed 1972 La Toile Daligram, Helena Devulina Diakanoff dit., GALA 1973 "Le Diners De Gala", an ornately illustrated cook book 1976 Gala Contemplating the Mediterranean Sea 1977 Dal's Hand Drawing Back the Golden Fleece in the Form of a Cloud to Show Gala Completely Nude, Very Far Away Behind the Sun (stereoscopical pair of paintings) 1983 Dal completes his final painting, The Swallow's Tail 2003 Destino, an animated short film originally a collaboration between Dal and Walt Disney, is released. Production on Destino began in 1945 The largest collections of Dal's work are at the Dal Theatre and Museum in Figueres, Catalonia, Spain, followed by the Salvador Dal Museum in St. Petersburg, Florida, which contains the collection of A. Reynolds Morse & Eleanor R. Morse. It holds over 1,500 works from Dal. Other particularly significant collections include the Reina Sofia Museum in Madrid and the Salvador Dal Gallery in Pacific Palisades, California. Espace Dal in Montmartre, Paris, France, as well as the Dal Universe in London, England, contain a large collection of his drawings and sculptures.

The unlikeliest venue for Dal's work was the Rikers Island jail in New York City; a sketch of the Crucifixion he donated to the jail hung in the inmate dining room for 16 years before it was moved to the prison lobby for safekeeping. Ironically, the drawing was stolen from that location in March 2003 and has not been recovered.[83]

[edit] Novels Under the encouragement of poet Federico Garca Lorca, Dal attempted an approach to a literary career through the means of the "pure novel". In his only literary production, Hidden Faces (1944), Dal describes, in vividly visual terms, the intrigues and love affairs of a group of dazzling, eccentric aristocrats who, with their luxurious and extravagant lifestyle, symbolize the decadence of the 1930s.

[edit] Gallery Gala in the Window (1933) Marbella. Rinoceronte vestido con puntillas (1956) Puerto Jos Bans. Homage to Newton (1985) Signed and numbered cast no. 5/8. Bronze with dark patina. Size: 388 x 210 x 133cm. UOB Plaza, Singapore

Dal's homage to Newton, with an open torso and suspended heart to indicate "open-heartedness," and an open head indicating "open-mindedness" the two very qualities important for science discovery and successful human endeavours. Children at Dali's exhibition in Sakp Sabanc Museum, Istanbul [edit] See also Little Ashes [edit] Notes 1.^ "Phelan, Joseph, ',The Salvador Dal Show". Artcyclopedia.com. http://www.artcyclopedia.com/feature2005-03.html. Retrieved 2010-08-22. 2.^ a b Dal, Salvador. (2000) Dal: 16 Art Stickers, Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-41074-9. 3.^ Ian Gibson (1997). The Shameful Life of Salvador Dal. W. W. Norton & Company. http://www.nytimes.com/books/first/g/gibson-dali.html. Gibson found out that "Dal" (and its many variants) is an extremely common surname in Arab countries like Morocco, Tunisia, Algeria or Egypt. On the other hand, also according to Gibson, Dal's mother family, the Domnech of Barcelona, had Jewish roots. 4.^ Saladyga, Stephen Francis. "The Mindset of Salvador Dal". lamplighter (Niagara University). Vol. 1 No. 3, Summer 2006. Retrieved July 22, 2006. 5.^ Birth certificate and "Dal Biography". Dal Museum. Dal Museum.

http://www.salvadordalimuseum.org/history/biography.html. Retrieved 2008-08-24. 6.^ Dal, The Secret Life of Salvador Dal, 1948, London: Vision Press, p.33 7.^ a b c d e f Llongueras, Llus. (2004) Dal, Ediciones B Mexico. ISBN 84-666-1343-9. 8.^ a b Rojas, Carlos. Salvador Dal, Or the Art of Spitting on Your Mother's Portrait, Penn State Press (1993). ISBN 0-27100842-3. 9.^ Salvador Dal. SINA.com. Retrieved on July 31, 2006. 10.^ Salvador Dal biography on astrodatabank.com. Retrieved September 30, 2006. 11.^ a b Dal, Secret Life, p.2 12.^ "Dal Biography 19041989 Part Two". artelino.com. http://www.artelino.com/articles/dali.asp. Retrieved 2006-0930. 13.^ Dal, Secret Life, pp.152153 14.^ As listed in his prison record of 1924, aged 20. However, his hairdresser and biographer, Luis Llongueras, states Dal was 1.74 m (5 ft 8 12 in) tall. 15.^ For more in-depth information about the Lorca-Dal connection see Lorca-Dal: el amor que no pudo ser and The Shameful Life of Salvador Dal, both by Ian Gibson. 16.^ a b Bosquet, Alain, Conversations with Dal, 1969. p. 1920. (PDF format) (of Garcia Lorca) 'S.D.:He was homosexual, as everyone knows, and madly in love with me. He tried to screw me twice .... I was extremely annoyed, because I wasnt homosexual, and I wasnt interested in

giving in. Besides, it hurts. So nothing came of it. But I felt awfully flattered vis--vis the prestige. Deep down I felt that he was a great poet and that I owe him a tiny bit of the Divine Dal's asshole. He eventually bagged a young girl, and she replaced me in the sacrifice. Failing to get me to put my ass at his disposal, he swore that the girls sacrifice was matched by his own: it was the first time he had ever slept with a woman.' 17.^ a b c Salvador Dal: Olga's Gallery. Retrieved on July 22, 2006. 18.^ "Paintings Gallery #5". Dali-gallery.com. http://www.dali-gallery.com/html/galleries/painting05.htm. Retrieved 2010-08-22. 19.^ Hodge, Nicola, and Libby Anson. The AZ of Art: The World's Greatest and Most Popular Artists and Their Works. California: Thunder Bay Press, 1996. Online citation. 20.^ "Phelan, Joseph". Artcyclopedia.com. http://www.artcyclopedia.com/feature-2005-03.html. Retrieved 2010-08-22. 21.^ Koller, Michael. Un Chien Andalou. senses of cinema January 2001. Retrieved on July 26, 2006. 22.^ a b c Shelley, Landry. "Dal Wows Crowd in Philadelphia". Unbound (The College of New Jersey) Spring 2005. Retrieved on July 22, 2006. 23.^ Gibson, Ian (1997). The shameful life of Salvador Dal. London: Faber and Faber. pp. 2389. ISBN 0-571-19380-3. 24.^ Clocking in with Salvador Dal: Salvador Dal's Melting Watches (PDF) from the Salvador Dal Museum. Retrieved on August 19, 2006.

25.^ a b Salvador Dal, La Conqute de lirrationnel (Paris: ditions surralistes, 1935), p. 25. 26.^ Current Biography 1940, pp219220 27.^ Luis Buuel, My Last Sigh: The Autobiography of Luis Buuel, Vintage 1984. ISBN 0816643873 28.^ Greeley, Robin Adle (2006). Surrealism and the Spanish Civil War, Yale University Press. p. 81. ISBN 0-30011295-5. 29.^ Jackaman, Rob. (1989) The Course of English Surrealist Poetry Since the 1930s, Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 0-88946932-6. 30.^ Current Biography 1940, p219 31.^ "Program Notes by Andy Ditzler (2005) and Deborah Solomon, ',Utopia Parkway:The Life of Joseph Cornell (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2003)". Andel.home.mindspring.com. http://andel.home.mindspring.com/cornell_notes.htm. Retrieved 2010-08-22. 32.^ Salvador Dal Exhibition, Exhibition Catalogue February 16 through May 15, 2005 33.^ http://philadelphia.about.com/od/salvador_dali/a/salvador_da li_a.htm 34.^ Bretell, Richard R. (1995). Impressionist paintings, drawings, and sculpture from the Wendy and Emery Reeves Collection. Dallas Museum of Art. ISBN 9780936227153. 35.^ a b Artcyclopedia: Salvador Dal. Retrieved September 4, 2006.

36.^ a b Descharnes, Robert and Nicolas. Salvador Dal. New York: Konecky & Konecky, 1993. p. 35. 37.^ Luis Buuel, My Last Sigh: The Autobiography of Luis Buuel (Vintage, 1984) ISBN 0816643873 38.^ a b c Dal's gift to exorcist uncovered Catholic News October 14, 2005 39.^ a b c Navarro, Vicente, PhD "The Jackboot of Dada: Salvador Dal, Fascist". Counterpunch. December 6, 2003. Retrieved July 22, 2006. 40.^ Lpez, Ignacio Javier. The Old Age of William Tell (A study of Buuel's Tristana). MLN 116 (2001): 295314. 41.^ The Phantasmagoric UniverseEspace Dal Montmartre. Bonjour Paris. Retrieved on August 22, 2006. 42.^ The History and Development of Holography. Holophile. Retrieved on August 22, 2006. 43.^ Hello, Dal. Carnegie Magazine. Retrieved on August 22, 2006. 44.^ Elliott H. King in Dawn Ades (ed.), Dal, Bompiani Arte, Milan, 2004, p. 456. 45.^ Salvador Dal Bio, Art on 5th. Retrieved July 22, 2006. Archived May 4, 2006 at the Wayback Machine. 46.^ Salvador Dal at Le Meurice Paris and St Regis in New York Andreas Augustin, ehotelier.com, 2007 47.^ "Scotsman review of Dirty Dal". The Scotsman. UK. http://living.scotsman.com/index.cfm?id=869862007. Retrieved 2010-08-22. 48.^ The Dali I knew By Brian Sewell, thisislondon.co.uk

49.^ Ian Gibson (1997). The Shameful Life of Salvador Dal. W. W. Norton & Company. 50.^ a b Excerpts from the BOE Website Herldica y Genealoga Hispana 51.^ Dal as "Marqus de Dal de Pbol" Boletn Oficial del Estado, the official gazette of the Spanish government 52.^ "Dal Resting at Castle After Injury in Fire". The New York Times. September 1, 1984. Retrieved July 22, 2006. 53.^ Mark Rogerson (1989). The Dal Scandal: An Investigation. Victor Gollancz. ISBN 0575037865. 54.^ Etherington -Smith, Meredith The Persistence of Memory: A Biography of Dal p. 411, 1995 Da Capo Press, ISBN 0306806622 55.^ Etherington -Smith, Meredith The Persistence of Memory: A Biography of Dal pp. xxiv, 411412, 1995 Da Capo Press, ISBN 0306806622 56.^ http://www.salvador-dali.org/en_index.html | The GalaSalvador Dal Foundation website 57.^ http://arsny.com/requested.html | Most frequently requested artists list of the Artists Rights Society 58.^ Salvador Dal, The Secret Life of Salvador Dal (New York: Dial Press, 1942), p. 317. 59.^ Michael Taylor in Dawn Ades (ed.), Dal (Milan: Bompiani, 2004), p. 342 60.^ a b Dal Universe Collection. County Hall Gallery. Retrieved on July 28, 2006. 61.^ a b "Salvador Dal's symbolism". County Hall Gallery. Retrieved on July 28, 2006

62.^ a b Lobster telephone. National Gallery of Australia. Retrieved on August 4, 2006. 63.^ Tate Collection | Lobster Telephone by Salvador Dal. Tate Online. Retrieved on August 4, 2006. 64.^ Federico Garca Lorca. Pegsos. Retrieved on August 8, 2006. 65.^ a b c Dal Rotterdam Museum Boijmans. Paris Contemporary Designs. Retrieved on August 8, 2006. 66.^ Past Exhibitions. Haggerty Museum of Art. Retrieved August 8, 2006. 67.^ "Dali & Film" Edt. Gale, Matthew. Salvador Dal Museum Inc. St Petersburg, Florida. 2007. 68.^ "L'ge d'Or (The Golden Age)" Harvard Film Archive. 2006. April 10, 2008. 69.^ Short, Robert. "The Age of Gold: Surrealist Cinema, Persistence of Vision" Vol. 3, 2002. 70.^ Elliott H. King, Dal, Surrealism and Cinema, Kamera Books 2007, p. 169. 71.^ a b Dal: Explorations into the domain of science. The Triangle Online. Retrieved August 8, 2006. 72.^ [Anon.] (1976). "Faenza-Goldmedaille fr SUOMI". Artis 29: 8. ISSN 0004-3842. 73.^ a b c Prose, Francine. (2000) The Lives of the Muses: Nine Women and the Artists they Inspired. Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-06-055525-4. 74.^ Lear, Amanda. (1986) My Life with Dal. Beaufort Books. ISBN 0825303737.

75.^ Lozano, Carlos. (2000) Sex, Surrealism, Dal, and Me. Razor Books Ltd. ISBN 0953820505. 76.^ Etherington-Smith, Meredith. (1995) The Persistence of Memory: A Biography of Dal. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0306806622. 77.^ Benefit of Clergy: Some Notes on Salvador Dali, by George Orwell 78.^ "Payne, Stanley G. THE A History of Spain and Portugal, Vol. 2, Ch. 26, p. 648651 (Print Edition: University of Wisconsin Press, 1973) (LIBRARY OF IBERIAN RESOURCES ONLINE Accessed May 15, 2007)". Libro.uca.edu. http://libro.uca.edu/payne2/payne26.htm. Retrieved 201008-22. 79.^ De la Cueva, Julio Religious Persecution, Anticlerical Tradition and Revolution: On Atrocities against the Clergy during the Spanish Civil War, Journal of Contemporary History Vol XXXIII 3, 1998 80.^ Salvador Dal pictured with Francisco Franco[dead link] 81.^ The Surreal World of Salvador Dal. Smithsonian Magazine. 2005. Retrieved August 31, 2006. 82.^ "The Salvador Dal Online Exhibit". MicroVision. http://www.daliweb.tampa.fl.us/collection.htm. Retrieved 2006-06-13. 83.^ a b "Dal picture sprung from jail". BBC. 2003-03-02. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/americas/2812683.stm. [edit] References Linde Sabler. "Dal". London: Haus Publishing, 2004 (paperback, ISBN 978-1-904341-75-8).

Salvador Dali interviewed by Mike Wallace on The Mike Wallace Interview April 19, 1985 [edit] External links Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Salvador Dal Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Salvador Dal

Biographies and news Dal's surreal wind-powered organ lacks only a rhinoceros UbuWeb: Salvador DalInterview and bank advertisement. Salvador Dal in the INA Archives A collection of interviews and footage of Dal in the French television The Master Visualizer Other links Salvador Dal at the Museum of Modern Art Article on Dal's religious faith The Salvador Dal photo library 60.000 photos Article on Dal's opera poem tre Dieu: opra-pome, audiovisuel et cathare en six parties (Being God: a Cathar Audiovisual Opera-Poem in Six Parts) Watch Un Chien Andalou at LikeTelevision Gala-Salvador Dal Foundation English language site St. Petersburg Dal Museum Kurutz, Steven, "Hello, Dali: Surrealist Museum Becomes a Reality", The Wall Street Journal Speakeasy blog, January 11,

2011, 4:46 pm ET. Interview with St. Petersburg (FL) museum director Dr. Hank Hine about new building. "The shameful life of Salvador Dal" (the witches of Llers)". Dal and Fages: "that intelligent and most cordial of collaborations" Exhibitions Espace DalThe unique permanent exhibition in France (Museum & Dal Fine Art Galleries) Dal & Film Tate Modern, London Museum-Gallery Xpo: Salvador Dal, Marquis de Pbol in Bruges Museum of Modern Art Union List of Artist Names, Getty Vocabularies. ULAN Full Record Display for Salvador Dal. Getty Vocabulary Program, Getty Research Institute. Los Angeles, California. Authority control: LCCN: n79021554 | VIAF: 64004109 v d eSalvador Dal

List of works

Selected paintings Landscape Near Figueras (1910) Vilabertran (1913) Fiesta in Figueres (191416) Port of Cadaqus (Night) (191819) The Artist's Father at Llane Beach (1920) The Garden of Llaner (Cadaqus) (192021) Cabaret Scene (1922) Cubist Self-Portrait with "La Publicitat" (1923)

Self-portrait with L'Humanitie (1923) Portrait of Luis Buuel (1924) Siphon and Small Bottle of Rum (1924) The Basket of Bread (1926) Honey Is Sweeter Than Blood (1927) The Lugubrious Game (1929) The First Days of Spring (1929) The Great Masturbator (1929) The Persistence of Memory (1931) The Ghost of Vermeer of Delft Which Can Be Used As a Table (1934) Morphological Echo (193436) Archaeological Reminiscence of Millet's Angelus (1935) Autumn Cannibalism (1936) Soft Construction with Boiled Beans (Premonition of Civil War) (1936) The Burning Giraffe (1937) Metamorphosis of Narcissus (1937) Swans Reflecting Elephants (1937) Apparition of Face and Fruit Dish on a Beach (1938) The Sublime Moment (1938) Shirley Temple, The Youngest, Most Sacred Monster of the Cinema in Her Time (1939) The Face of War (1940) Slave Market with the Disappearing Bust of Voltaire (1940) Honey is Sweeter than Blood (1941) Geopoliticus Child Watching the Birth of the New Man (1943) Dream Caused by the Flight of a Bee Around a Pomegranate a Second Before Awakening (1944) Galarina (194445) Basket of Bread (1945) The Temptation of St. Anthony (1946) The Elephants (1948) Leda Atomica (1949) The Madonna of Port Lligat (1949) Christ of Saint John of the Cross (1951) Galatea of the Spheres (1952) The Disintegration of the Persistence of Memory (195254) Crucifixion (Corpus Hypercubus) (1954) Young Virgin AutoSodomized by the Horns of Her Own Chastity (1954) The Sacrament of the Last Supper (1955) Living Still Life (1956) The Discovery of America by Christopher Columbus (1958 59) The Ecumenical Council (195960) Galacidalacidesoxyribonucleicacid (1963) Tuna Fishing (196667) The Hallucinogenic Toreador (196870) La Toile Daligram (1972) The Swallow's Tail (1983)