Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Bibi PS

Uploaded by

Asad Ali KhanOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Bibi PS

Uploaded by

Asad Ali KhanCopyright:

Available Formats

12 October 2011 PRESS SUMMARY R (on the application of Quila and another) (FC) (Respondents) v Secretary of State for

the Home Department (Appellant); R (on the application of Bibi and another) (FC) (Respondents) v Secretary of State for the Home Department (Appellant) [2011] UKSC 45

On appeal from [2010] EWCA Civ 1482; [2009] EWHC Admin 3189

JUSTICES: Lord Phillips (President); Lady Hale; Lord Brown; Lord Clarke; Lord Wilson.

BACKGROUND TO THE APPEALS The issue is whether the ban on the entry for settlement of foreign spouses or civil partners unless both parties are aged 21 or over, contained in paragraph 277 of the Immigration Rules, was a lawful way of deterring or preventing forced marriages. Paragraph 277 of the Immigration Rules [Paragraph 277] was amended with effect from 27 November 2008 to raise the minimum age for a person either to be granted a visa for the purposes of settling in the United Kingdom as a spouse or to sponsor another for the purposes of obtaining such a visa from 18 to 21. The purpose of the amendment was not to control immigration but to deter forced marriages. A forced marriage is a marriage into which at least one party enters without her or his free and full consent through force or duress, including coercion by threats or other psychological means. Mr Quila, a Chilean national, entered into a fully consensual marriage with Ms Jeffery, a British citizen. Mr Aguilar Quila applied for a marriage visa before the amendment took effect, but his application was refused as his wife was only 17 and a sponsoring spouse had to be 18. By the time that Ms Jeffrey had turned 18 the amendment was in force and the Home Office refused to waive it. Consequently, Mr Quila and his wife were forced to leave the UK initially to live in Chile (his wife having had to relinquish a place to study languages at Royal Holloway, University of London) and subsequently to live in Ireland. Bibi (as she invited the Court to describe her) is a Pakistani national who applied to join her husband, Mohammed, a British citizen, in the UK. Bibi and Mohammed had an arranged marriage in Pakistan in October 2008, to which each of them freely consented. Their application was refused as both parties were under 21. The Respondents claims for judicial review of the decisions were both rejected in the High Court. The Respondents successfully appealed to the Court of Appeal, which declared that the application of Paragraph 277 so as to refuse them marriage visas was in breach of their rights under Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms 1950 [the ECHR]. The Secretary of State has appealed to the Supreme Court. JUDGMENT The Supreme Court, by a 4-1 majority, dismisses the Secretary of States appeal on the grounds that the refusal to grant marriage visas to the Respondents was an infringement of their rights under Article 8 ECHR. Lord Wilson gives the leading judgment; Lady Hale gives a concurring judgment. Lord Phillips and Lord Clarke agree with Lord Wilson and Lady Hale. Lord Brown gives a dissenting judgment. REASONS FOR THE JUDGMENT Article 8 ECHR was engaged [43; 72]. Applying R (Razgar) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2004] UKHL 27, the relevant question was whether there had been an interference by a public authority with the exercise of a persons right to respect for his private or family life and if so, whether it had had consequences of sufficient gravity to engage the operation of the article [30]. Unconstrained by authority,

The Supreme Court of the United Kingdom Parliament Square London SW1P 3BD T: 020 7960 1886/1887 F: 020 7960 1901 www.supremecourt.gov.uk

Lord Wilson would have considered it a colossal interference to require for up to three years either that the spouses should live separately or that a British citizen should leave the UK for up to three years [32]. The ECtHR in Abdulaziz v United Kingdom (1985) 7 EHRR 471 has, however, held that there was no lack of respect for family life in denying entry to foreign spouses. There was no positive obligation on the State to respect a couples choice of country of matrimonial residence [35 - 36]. Lord Wilson holds that Abdulaziz should not be followed in this respect; there was dissent at the time and no clear and consistent subsequent jurisprudence from the ECtHR as four more recent decisions [38 41] were inconsistent with the decision [43]. The ECtHR has since recognized that the distinction between positive and negative obligations should not generate different outcomes [43]. The Secretary of State has failed to establish that the interference with the Respondents rights to a family life was justified under Article 8(2) ECHR. Paragraph 277 has a legitimate aim, namely the protection of the rights and freedoms of those who might be forced into marriage [45] and is rationally connected to that objective, but its efficacy is highly debatable [58]. A number of questions remain unanswered including how prevalent the motive of applying for UK citizenship is in the genesis of forced marriages; whether the forced marriage would have occurred in any event and thus the rule increase the control of victims abroad and whether the amendment might precipitate a swift pregnancy in order to found an application for a discretionary grant of a visa [49]. The Secretary of State has failed to adduce any robust evidence that the amendment would have any substantial deterrent effect [50; 75]. By contrast, the number of forced marriages amongst those refused a marriage visa had not been quantified [53]. The only conclusion that could be drawn was that the amendment would keep a very substantial number of bona fide young couples apart or forced to live outside the UK [54], vastly exceeding the number of forced marriages that would be deterred [58; 74]. The measure was similar to the blanket prohibition on persons subject to immigration control marrying without the Secretary of States written permission found to be unlawful in R (Baiai) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2008] UKHL 53 [57, 78 - 79]. The Secretary of State has failed to exercise her judgement on this imbalance and thus failed to establish both that the measure is no more than is necessary to accomplish the objective of deterring forced marriage and that it strikes a fair balance between the rights of parties to unforced marriages and the interests of the community in preventing forced marriage. On any view, the measure was a sledgehammer but the Secretary of State has not attempted to identify the size of the nut [58]. Lady Hale holds that the debate on Abdulaziz is something of a red herring as the Secretary of State could not simultaneously state that the measure was not for the purpose of controlling immigration and rely upon jurisprudence wholly premised on the States right to control immigration [72]. She further holds that the restriction was automatic and indiscriminate [74]; failed to detect forced marriages and imposed a delay on cohabitation in the country of choice, which was a deterrent that could impair the essence of the right to marry under Article 12 ECHR [78 -79]. Whilst the judgment is essentially individual, it is hard to conceive that the Secretary of State could avoid infringement of Article 8 ECHR when applying Paragraph 277 to an unforced marriage [59; 80]. Lord Brown, dissenting, holds the extent of forced marriage is impossible to quantify so the deterrent effect of Paragraph 277 could never be satisfactorily determined [87]. The judgement of how to balance the enormity of suffering within forced marriages with the disruption to innocent couples was one for elected politicians, not for judges [91]. The measure was not an automatic indiscriminate restriction [92]; would be disapplied in exceptional circumstances [93] and similar rules applied in other European countries [85]. To disapply the rule would exceed ECtHR jurisprudence and in such a sensitive context, government policy should not be frustrated except in the clearest cases [97]. References in square brackets are to paragraphs in the judgment NOTE This summary is provided to assist in understanding the Courts decision. It does not form part of the reasons for the decision. The full judgment of the Court is the only authoritative document. Judgements are public documents and are available at: www.supremecourt.gov.uk/decided-cases/index.html

The Supreme Court of the United Kingdom Parliament Square London SW1P 3BD T: 020 7960 1886/1887 F: 020 7960 1901 www.supremecourt.gov.uk

You might also like

- Westlaw India Delivery Summar1Document8 pagesWestlaw India Delivery Summar1nirali katiraNo ratings yet

- Akhter V Khan (2020) 2 FLR 139Document35 pagesAkhter V Khan (2020) 2 FLR 139timid189No ratings yet

- Impact of Article 8 ECHR on UK family visa applicationsDocument3 pagesImpact of Article 8 ECHR on UK family visa applicationssawera javaidNo ratings yet

- Family LO CompilationDocument40 pagesFamily LO CompilationMerice KizitoNo ratings yet

- Family Law CasesDocument16 pagesFamily Law Casespenney02No ratings yet

- UKSC rules on financial provision for cohabiting couplesDocument23 pagesUKSC rules on financial provision for cohabiting couplesCitizen Kwadwo AnsongNo ratings yet

- HOUSE OF LORDS RULES CONTROL ORDER DOES NOT DEPRIVE MAN OF LIBERTYDocument16 pagesHOUSE OF LORDS RULES CONTROL ORDER DOES NOT DEPRIVE MAN OF LIBERTYMax WormNo ratings yet

- Carlos Vs Sandoval. GR 179922Document3 pagesCarlos Vs Sandoval. GR 179922Lu CasNo ratings yet

- Perserverance SuccessionDocument11 pagesPerserverance SuccessionRuvimbo MakwindiNo ratings yet

- Court Upholds Post-Nuptial Agreement in Ancillary Relief CaseDocument4 pagesCourt Upholds Post-Nuptial Agreement in Ancillary Relief CaseAnnNo ratings yet

- Ground For DivorceDocument9 pagesGround For DivorcechalikosaelvisNo ratings yet

- Gumede V President 2008Document3 pagesGumede V President 2008Chenai ChiviyaNo ratings yet

- Case Note 2019 - Swift V Secretary of State For Justice (2013)Document3 pagesCase Note 2019 - Swift V Secretary of State For Justice (2013)ماتو اریکاNo ratings yet

- Jurisdiction Over Annulment DecreesDocument20 pagesJurisdiction Over Annulment DecreesCristine LecNo ratings yet

- Matrimonial Causes ActDocument26 pagesMatrimonial Causes Actchloeabisai.03No ratings yet

- Chapter 4 MARRIAGE FINALS Essential RequisitesDocument38 pagesChapter 4 MARRIAGE FINALS Essential RequisitesJose AlinaoNo ratings yet

- Succession To The Crown Bill 2015Document8 pagesSuccession To The Crown Bill 2015Sina Hafezi MasoomiNo ratings yet

- Essay For Nullity Grade BDocument5 pagesEssay For Nullity Grade BAngelene SelwanathanNo ratings yet

- New Cases Summaries 2022. UploadDocument5 pagesNew Cases Summaries 2022. UploadTheodorah NgobeniNo ratings yet

- 08 Chapter 4Document145 pages08 Chapter 4priyankaNo ratings yet

- First. - Against Her Will Secondly. - Without Her ConsentDocument9 pagesFirst. - Against Her Will Secondly. - Without Her ConsentKumar AdityaNo ratings yet

- Republic Vs AlbiosDocument8 pagesRepublic Vs AlbiosRileyNo ratings yet

- Case Digest Garcia vs. RecioDocument2 pagesCase Digest Garcia vs. RecioDarielle FajardoNo ratings yet

- Special Marriage Act provisions for interfaith unionsDocument28 pagesSpecial Marriage Act provisions for interfaith unionsVed AntNo ratings yet

- Republic V AlbiosDocument8 pagesRepublic V Albiosmel bNo ratings yet

- TQ V TR (CA, 2009)Document43 pagesTQ V TR (CA, 2009)Harpott GhantaNo ratings yet

- FamilyDocument18 pagesFamilyFranklin DorobaNo ratings yet

- Has Muslim personal law been given recognition in the light of the recent appeal court judgmentDocument6 pagesHas Muslim personal law been given recognition in the light of the recent appeal court judgment221083901No ratings yet

- Court of Appeal human rights immigration cheat sheetDocument1 pageCourt of Appeal human rights immigration cheat sheetGovernor007No ratings yet

- 79.1 Enrico vs. Heirs of Sps. Medinaceli DigestDocument2 pages79.1 Enrico vs. Heirs of Sps. Medinaceli DigestEstel Tabumfama100% (1)

- 20210808-Mr G. H. Schorel-Hlavka O.W.B. To Reece Kershaw Chief Commissioner of The Australian Federal Police-COMPLAINT-Suppl-02Document35 pages20210808-Mr G. H. Schorel-Hlavka O.W.B. To Reece Kershaw Chief Commissioner of The Australian Federal Police-COMPLAINT-Suppl-02Gerrit Hendrik Schorel-HlavkaNo ratings yet

- Brexit and Parliamentary SovereigntyDocument17 pagesBrexit and Parliamentary Sovereigntysheik muhtasimNo ratings yet

- AM (Zimbabwe) V Secretary of State For The Home Department-3Document10 pagesAM (Zimbabwe) V Secretary of State For The Home Department-3mcNo ratings yet

- Lightman of The High Court-Chancery Division-Fitzgibbon V HM AGDocument6 pagesLightman of The High Court-Chancery Division-Fitzgibbon V HM AG6PacmanNo ratings yet

- Void and Voidable MarriagesDocument21 pagesVoid and Voidable MarriagesMartin KiruleNo ratings yet

- Khor Chin Miaw V Frank TheodorusDocument16 pagesKhor Chin Miaw V Frank TheodorusNurin IlyanaNo ratings yet

- Australia - Case Law - Minster of State For Immigration and Ethnic Affairs V Ah Hin Teoh - 1995 - EngDocument33 pagesAustralia - Case Law - Minster of State For Immigration and Ethnic Affairs V Ah Hin Teoh - 1995 - EngsarveenahNo ratings yet

- Evasion of Law and Mandatory Rules in PIL - FawcettDocument20 pagesEvasion of Law and Mandatory Rules in PIL - FawcettNathania AisyaNo ratings yet

- 3 (Allowed) PDF Hamalainen V Finland - (2014) 37 BHRC 55Document32 pages3 (Allowed) PDF Hamalainen V Finland - (2014) 37 BHRC 55NurHafizahNasirNo ratings yet

- CCZ 12-15 - MUDZURU V THE MINISTER OF JUSTICE LEGAL PARL AFFAIRS - 0Document60 pagesCCZ 12-15 - MUDZURU V THE MINISTER OF JUSTICE LEGAL PARL AFFAIRS - 0Malcom GumboNo ratings yet

- Norbett Helmut Hutzler v. Immigration & Naturalization Service, 21 F.3d 1121, 10th Cir. (1994)Document3 pagesNorbett Helmut Hutzler v. Immigration & Naturalization Service, 21 F.3d 1121, 10th Cir. (1994)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court upholds validity of marriage contracted for immigration purposesDocument34 pagesSupreme Court upholds validity of marriage contracted for immigration purposesTsungkodong TweetysumNo ratings yet

- Parliamentary Supremacy and Constitutional Entrenchment in New ZealandDocument33 pagesParliamentary Supremacy and Constitutional Entrenchment in New ZealandRitika PathakNo ratings yet

- Marriage Requirements and ValidityDocument8 pagesMarriage Requirements and ValidityJake CopradeNo ratings yet

- Conflict AnirudhDocument28 pagesConflict AnirudhAnirudh AroraNo ratings yet

- Communications During MarriageDocument11 pagesCommunications During MarriageVibhu TeotiaNo ratings yet

- Revision Notes of Family Law HKDocument33 pagesRevision Notes of Family Law HKhibaNo ratings yet

- Family LW CourseworkDocument6 pagesFamily LW CourseworkKakooza TimothyNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines, Petitioner, vs. Llberty D. Albios, RespondentDocument10 pagesRepublic of The Philippines, Petitioner, vs. Llberty D. Albios, RespondentPiayaNo ratings yet

- ADR Judgment - 16.04.20 Approved Transcript High CourtDocument12 pagesADR Judgment - 16.04.20 Approved Transcript High CourtBritCitsNo ratings yet

- Gian Bee Choo Vs Meng Xianhui (2019) 5 SLR 0812Document46 pagesGian Bee Choo Vs Meng Xianhui (2019) 5 SLR 0812Jordan KowNo ratings yet

- Note Introduction. This Rule Is Reproduced Verbatim From CPLR 4502 (SeeDocument4 pagesNote Introduction. This Rule Is Reproduced Verbatim From CPLR 4502 (SeeJerma Cam EspejoNo ratings yet

- Digest - REPUBLIC V ALBIOS GR NO 198780Document2 pagesDigest - REPUBLIC V ALBIOS GR NO 198780DanicaNo ratings yet

- Fujiki Vs MarinayDocument3 pagesFujiki Vs MarinayPaolo MendioroNo ratings yet

- Othniel Edgar Small v. Immigration and Naturalization Service, 438 F.2d 1125, 2d Cir. (1971)Document4 pagesOthniel Edgar Small v. Immigration and Naturalization Service, 438 F.2d 1125, 2d Cir. (1971)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Legal System and Method Casenote (UofL 2019)Document3 pagesLegal System and Method Casenote (UofL 2019)Izmail PirzadaNo ratings yet

- Netherlands Law On Same Sex MarriageDocument4 pagesNetherlands Law On Same Sex MarriageSuiNo ratings yet

- Marriage Act Cap 150Document26 pagesMarriage Act Cap 150Edwin ObalaNo ratings yet

- ICJ VerdictDocument42 pagesICJ VerdictThe Indian Express100% (1)

- KashmirUpdateReport 8july2019Document43 pagesKashmirUpdateReport 8july2019muhammad aliNo ratings yet

- Climate Change - An Existential Challenge For Pakistan (Friday, 3 May 2019 & Saturday, 4 May 2019)Document2 pagesClimate Change - An Existential Challenge For Pakistan (Friday, 3 May 2019 & Saturday, 4 May 2019)Asad Ali KhanNo ratings yet

- Benchmark FinesDocument1 pageBenchmark FinesAsad Ali KhanNo ratings yet

- Islam News PaperDocument1 pageIslam News PaperAsad Ali KhanNo ratings yet

- White PaperDocument104 pagesWhite PaperZerohedgeNo ratings yet

- Draft Withdrawal AgreementDocument119 pagesDraft Withdrawal AgreementEwan OwenNo ratings yet

- Pakistan's Foreign RelationsDocument25 pagesPakistan's Foreign RelationsAsad Ali KhanNo ratings yet

- The Pakistan Institute of International Affairs, Conference On Peace in South Asia: Opportunities and Challenges 15-16 November 2017Document3 pagesThe Pakistan Institute of International Affairs, Conference On Peace in South Asia: Opportunities and Challenges 15-16 November 2017Asad Ali Khan100% (1)

- Dr. Masuma Hasan (Speech) 1 October 2016-1Document2 pagesDr. Masuma Hasan (Speech) 1 October 2016-1Asad Ali KhanNo ratings yet

- Remedies For Forced Marriage A HANDBOOK FOR LAWYERSDocument57 pagesRemedies For Forced Marriage A HANDBOOK FOR LAWYERSAsad Ali KhanNo ratings yet

- Fatehyab Ali Khan 2015Document4 pagesFatehyab Ali Khan 2015Asad Ali KhanNo ratings yet

- MAD LinklatersDocument19 pagesMAD LinklatersAsad Ali KhanNo ratings yet

- Nazam Bnam Perween by Anwar RashidDocument1 pageNazam Bnam Perween by Anwar RashidAsad Ali KhanNo ratings yet

- Immigration BillDocument113 pagesImmigration BillAsad Ali KhanNo ratings yet

- U.S. Fcpa 1977Document16 pagesU.S. Fcpa 1977Asad Ali KhanNo ratings yet

- Fatehyab Ali Khan 3rd AnniversaryDocument1 pageFatehyab Ali Khan 3rd AnniversaryAsad Ali KhanNo ratings yet

- Proprietary Trading ReportDocument53 pagesProprietary Trading ReportAsad Ali KhanNo ratings yet

- FSA Final Notice To UBS Re LIborDocument40 pagesFSA Final Notice To UBS Re LIborAsad Ali KhanNo ratings yet

- FSA V Sinaloa Gold JudgmentDocument19 pagesFSA V Sinaloa Gold JudgmentAsad Ali KhanNo ratings yet

- Prudential PLC - The Privilege JudgmentDocument53 pagesPrudential PLC - The Privilege JudgmentAsad Ali KhanNo ratings yet

- FSA LIBOR Internal Audit ReportDocument103 pagesFSA LIBOR Internal Audit ReportAsad Ali KhanNo ratings yet

- Rental Power Plants OrderDocument3 pagesRental Power Plants OrderAsad Ali KhanNo ratings yet

- Anti Bribery and Corruption GuideDocument40 pagesAnti Bribery and Corruption GuideAsad Ali KhanNo ratings yet

- Pakistan SC's Judgment Against The PMDocument90 pagesPakistan SC's Judgment Against The PMBar & BenchNo ratings yet

- An Inspection of The UK Border Agency's Handling of Legacy Asylum and Migration CasesDocument76 pagesAn Inspection of The UK Border Agency's Handling of Legacy Asylum and Migration CasesAsad Ali KhanNo ratings yet

- House of Lords, House of Commons Parliamentary Commission On Banking StandardsDocument144 pagesHouse of Lords, House of Commons Parliamentary Commission On Banking StandardsAsad Ali KhanNo ratings yet

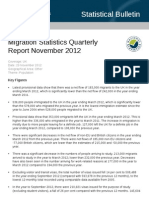

- ONS Migration November 2012Document38 pagesONS Migration November 2012Asad Ali KhanNo ratings yet

- FCPA Opinion ProcedureDocument4 pagesFCPA Opinion ProcedureAsad Ali KhanNo ratings yet

- Implementing Wheatley PDFDocument50 pagesImplementing Wheatley PDFAsad Ali KhanNo ratings yet

- CRG 660Document2 pagesCRG 660Softnyx NazrinNo ratings yet

- 1) Define Tort. Explain The Maxim Injuria Sine Damnum', Damnum Sine Injuria'Document54 pages1) Define Tort. Explain The Maxim Injuria Sine Damnum', Damnum Sine Injuria'Ñîßhíthà Göpàläppã100% (1)

- Lesson 4 PbaDocument3 pagesLesson 4 Pbaapi-254422585No ratings yet

- Supreme Court's Arbitrary Awards for Human Rights ViolationsDocument5 pagesSupreme Court's Arbitrary Awards for Human Rights ViolationsSajid SheikhNo ratings yet

- Leg ProDocument75 pagesLeg ProVanessa MarieNo ratings yet

- Topnotcher OrdinanceDocument2 pagesTopnotcher Ordinancesteve geocadinNo ratings yet

- Essay On Indian Judiciary SystemDocument4 pagesEssay On Indian Judiciary SystemSoniya Omir Vijan67% (3)

- Statutory ConstructionDocument10 pagesStatutory ConstructionMikey CupinNo ratings yet

- Moot Court Respondent FinalDocument18 pagesMoot Court Respondent FinalDanyal Ahmed100% (1)

- AN ANALYSIS OF THE S.R. BOMMAI JUDGMENT'S IMPACT ON PRESIDENT'S RULEDocument7 pagesAN ANALYSIS OF THE S.R. BOMMAI JUDGMENT'S IMPACT ON PRESIDENT'S RULEBodhiratan BartheNo ratings yet

- The Codification of International Law 2Document40 pagesThe Codification of International Law 2doctrineNo ratings yet

- Constitution of The Union of Burma (1947) enDocument69 pagesConstitution of The Union of Burma (1947) enPugh Jutta100% (2)

- Revised IRR of GCTA Law Excludes Heinous Crime ConvictsDocument7 pagesRevised IRR of GCTA Law Excludes Heinous Crime ConvictsMelvin PernezNo ratings yet

- CSC Ruling on Salary Deductions for Weekend DaysDocument5 pagesCSC Ruling on Salary Deductions for Weekend DaysGhee MoralesNo ratings yet

- Native Title and the Regalian DoctrineDocument21 pagesNative Title and the Regalian DoctrineThereseSunicoNo ratings yet

- III Constitutional Governance-IDocument1 pageIII Constitutional Governance-IShaman KingNo ratings yet

- Civil divorce decree obtained abroad recognized in PhilippinesDocument2 pagesCivil divorce decree obtained abroad recognized in PhilippinesSheNo ratings yet

- Legal Research: LARIN, Christian John VDocument14 pagesLegal Research: LARIN, Christian John VJason ToddNo ratings yet

- Admin Code of 1987Document75 pagesAdmin Code of 1987Kimberly SendinNo ratings yet

- Aldaba Vs ComelecDocument17 pagesAldaba Vs ComelecAbombNo ratings yet

- CH 5 Fill in The BlanksDocument4 pagesCH 5 Fill in The BlanksdlreiffensteNo ratings yet

- Sda Gen KnowledgeDocument26 pagesSda Gen KnowledgeRuchithaNo ratings yet

- Cruz vs. YoungbergDocument2 pagesCruz vs. YoungbergMark SantiagoNo ratings yet

- P. Ramachandra Rao Vs State of KarnatakaDocument2 pagesP. Ramachandra Rao Vs State of Karnatakagparth247No ratings yet

- Puyat v. de Guzman (Sec. 14)Document2 pagesPuyat v. de Guzman (Sec. 14)Carlota Nicolas Villaroman100% (1)

- Felipe Ysmael, Jr. & Co., Inc. vs. Deputy ExecutiveDocument15 pagesFelipe Ysmael, Jr. & Co., Inc. vs. Deputy ExecutiveButch MaatNo ratings yet

- Fundamental Duties in Indian ConstitutionDocument4 pagesFundamental Duties in Indian ConstitutionshivaNo ratings yet

- Ch. - 1 - The French Revolution - Extra Questions and NotesDocument24 pagesCh. - 1 - The French Revolution - Extra Questions and NoteskripaNo ratings yet

- 100 Days Action Plan English Medium Social StudiesDocument29 pages100 Days Action Plan English Medium Social Studiesapi-79737143100% (2)

- Tootle v. Uitenham, 10th Cir. (2004)Document3 pagesTootle v. Uitenham, 10th Cir. (2004)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet