Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Korea's Green Growth Strategy: A Washington Perspective

Uploaded by

Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Korea's Green Growth Strategy: A Washington Perspective

Uploaded by

Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)Copyright:

Available Formats

Volume 27

KOREAS ECONOMY

2 0 1 1

a publication of the Korea Economic Institute and

the Korea Institute for International Economic Policy

30848_Cover_Assembled-R1.indd 1 7/13/11 6:40 PM

KEI Editorial Board

KEI Editors: Florence Lowe-Lee

Troy Stangarone

Contract Editor: Mary Marik

1 k l l A k

A k l l l

C k k 1

u I

k u5

C

kLl

1 W

k L l

C 8 u A C

8

A C

A C l S kLl

Copyright k L l A

u S A

A 8 8

ISSN 1054-6944

Volume 27

Part I: Overview and Macroeconomic Issues

Commentary

Korea and the World Economy 1

C. Fred Bergsten

Koreas Challenges and Opportunities in 2011 3

Chae Wook

Analysis

Korea: Economic Prospects and Challenges after the 6

Global Recession

Subir Lall and Meral Karasulu

Part II: Financial Institutions and Markets -

Focus on Green Growth

Commentary

Korean Green Growth in a Global Context 13

Han Seung-soo

An Ocean of Trouble, An Ocean of Opportunity 15

Philippe Cousteau and Andrew Snowhite

Analysis

System Architecture for Effective 18

Green Finance in Korea

Kim Hyoung-tae

Koreas Green Growth Strategy: 25

A Washington Perspective

Haeyoung Kim

Part III: The Seoul G-20

Commentary

A Reflection on the Seoul Summit 31

Paul Volcker

The G-20: Achievements and Challenges 33

SaKong Il

Volume 27

KOREAS ECONOMY

2 0 1 1

Volume 27

Part III: The Seoul G-20 (Continued)

Analysis

Achievements in Seoul and Koreas Role in the G-20 35

Choi Heenam

Africa and South Koreas Leadership of the G-20 42

Mwangi S. Kimenyi

Part IV: External Relations

Commentary

Koreas Green Energy Policies and Prospects 49

Whang Jooho

Analysis

Economic Implications for South Korea of the Current 52

Transformation in the Middle East

Han Baran

Korea-Africa: Emerging Opportunities 59

Philippe de Pontet and James Clifton Francis

U.S.-Korea Economic Relations: A View from Seoul 67

Kim Won-kyong

Part V: Korea-China Economic Relations

Commentary

A New Phase in ChinaNorth Korea Relations 73

Gordon G. Chang

Analysis

Increasing Dependency: North Koreas Economic 75

Relations with China

Dick K. Nanto

Korea-China Economic Partnership: 84

The Third China Rush

Cheong Young-rok and Lee Chang-kyu

Part VI: North Koreas Economic Development and

External Relations

Commentary

Human Resources and Korean Reunification 97

Nicholas Eberstadt

Analysis

The Economics of Reunification 99

Dong Yong-sueng

Leading Economic Indicators for Korea 105

About KEI 106

KEI Advisory Board 107

FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS AND MARKETSFOCUS ON GREEN GROWTH 25

KOREAS GREEN GROWTH STRATEGY: A WASHINGTON PERSPECTIVE

By Haeyoung Kim

When the global financial crisis tore through world

economies, national budgets around the world were

immediately funneled to stabilize and revive the

energy-intensive industries impacted by the market

maelstrom. Yet, the Republic of Korea (ROK) saw

the fiscal downturn as an opportunity to invest in

new engines to power its economic growth. In a 2008

national address commemorating the 60th anniversary

of Koreas liberation from Japanese colonial rule,

South Korean president Lee Myung-bak announced

a low carbon, green growth vision for his countrys

economic future.

The ROKs National Green Growth Vision

As the global community turns its attention to climate

change and clean energy, the worlds 12th-largest

economy has taken aggressive steps to lead the effort.

Seoul pledged to earmark 80 percent of its $38 billion

postcrisis stimulus package and 2 percent of its annual

budget over the course of five years to advance green

growth.

1

According to the United Nations Environment

Program, the ROK has dedicated the highest propor-

tion among comparable country members of the Group

of 20 (G-20) of its fiscal stimulus package to green

projects and is setting aside double what most other

G-20 states have as a percentage of GNP.

The ROK government aims by 2020 to reduce coun-

trywide emissions by 30 percent relative to a business-

as-usual baseline, which is 4 percent below 2005 levels

and a near doubling of the recommended targets set by

the international community. The nation also calls for

6 percent of its energy needs to be met by wind, solar,

and other renewable sourcesa significant increase

from the modest 1.68 percent of renewables used

today. Classified under the Kyoto Protocol as a non

Annex I party, or a developing economy, the ROK is

not bound by emissions targets.

2

Nevertheless, Seoul

has voluntarily undertaken zealous efforts to reduce

carbon emissions.

The ROKs goals are indeed ambitious given that the

countrys current level of energy consumption and car-

bon dioxide (CO

2

) emissions rank among the highest

in the world (Figure 1). The country is the 10th-largest

world energy consumer, 5th-largest global crude oil net

importer, and the 2nd-largest buyer of liquefied natu-

ral gas and coal. Among OECD countries, the ROK

is the 9th-largest emitter of CO

2

, and its greenhouse

1. In comparison, the United States dedicated 11.6 percent of its $972.1 billion stimulus package to green technology, while Japan

dedicated 2 percent of its $485.9 billion package to the same.

2. Given South Koreas status when the Kyoto Protocol of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change was

being negotiated, the country was classied as a nonAnnex I party.

The ROK government aims by 2020 to reduce

countrywide emissions by 30 percent relative to a

business-as-usual baseline, which is 4 percent below

2005 levels and a near doubling of the recommend-

ed targets set by the international community.

A year later, the government introduced the National

Strategy for Green Growth, and in January 2010 South

Koreas National Assembly passed the Framework Act

on Low-Carbon Green Growth, codifying a 50-year

plan to address climate change and achieve greater

energy independence without compromising the

countrys economy. Sharing a common commitment

to decarbonize, the United States and the ROK have

also cooperated around developing clean-energy tech-

nologies, establishing new features to a long-standing

alliance relationship. Although skepticism around the

details of low carbon, green growth remain, particular-

ly megascale power generating projects and a proposed

carbon-trading system, Seoul has made considerable

efforts in recent years to back green growth.

26 THE KOREA ECONOMIC INSTITUTE

gas emissions growth rates are the highest in the last

two decades, nearly doubling from 298 million tons

in 1990 to 594 million tons by 2005.

short period of time, the country has experienced

profound economic shifts. From a donor-dependent,

war-torn country, South Korea transformed itself into

a leading global economy. Annual per capita income

increased from $100 in 1960, to $1,674 by 1980,

$10,884 in 2000, and $27,560 in 2010.

4

Unfortunately, the industry-focused growth paradigm

that enabled the ROK to spectacularly emerge from

poverty also entailed massive environmental costs.

The Han River, which flows through Seoul, once

doubled as the citys sewage line and was inundated

by unregulated dumping of large-scale industrial

waste. The countrys other major riversthe Nakdong,

Yeongsan, and Geumdid not fare much better. In

fact, water quality was so severely damaged during

the period of intense industrialization that these rivers

failed to meet the minimum standards of potable water

for the related metropolitan areas. Not until the late

1980s, in advance of hosting the Olympics in 1988, did

the government begin in earnest to revive the health

of its major rivers.

With a dramatic increase in energy consumption to

power developing industries, air pollution in Seoul also

reached record levels. From 1966 to 1975, petroleum

consumption increased from roughly 15,000 barrels

to 105,000 barrels per day. During that same time,

coal consumption nearly doubled from 10 million to

20 million tons per year.

5

The burgeoning use of mo-

tor vehicles also made significant contributions to the

nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide, and carbon dioxide

levels in the airpollution levels that have steadily

increased ever since (Figure 2). Rapid postwar devel-

opment efforts in a resource-scarce, densely populated,

geographically small country placed enormous pressure

on the ROKs ecosystem, a heavy price to pay as the

country emerged as a leading Asian Tiger economy.

Environmental Politics in Postwar Korea

During the period of authoritarian rule in the 1960s and

1970s, the ROK government pursued rapid moderniza-

tion with few, if any, environmental controls. Emerg-

3. Statistics and Balances (database), International Energy Agency, Paris, http://iea.org/stats/.

4. International Financial StatisticsCountry Tables, International Monetary Fund, Washington, D.C., www.imfstatistics.org/imf.

5. Korea National Statistics Ofce, www.nso.go.kr.

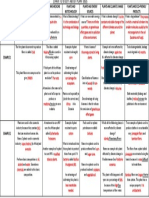

0

1,000

2,000

3,000

4,000

5,000

6,000

7,000

8,000

9,000

European Union

High income: OECD

Japan

United States

Republic of Korea (ROK)

2

0

0

9

2

0

0

5

2

0

0

0

1

9

9

5

1

9

9

0

1

9

8

5

1

9

8

0

1

9

7

5

1

9

7

0

Figure 1: Energy Use in Selected Countries and

Areas, 19702009, kilograms of oil equivalent per

capita

Kilograms of oil equivalent per capita

Sources: World Development Indicators, World Development

Finance, World Bank, Washington, D.C., various years.

Efforts to diversify energy sources will require a fun-

damental transformation of the ROKs consumption

patterns. In 2008, oil accounted for nearly 50 percent

of the countrys total consumption mix, nuclear

power nearly 30 percent, coal 7 percent, natural gas

12 percent, and renewables roughly 2 percent of total

usage.

3

With 57 percent of these resources consumed

in heavy industry, a shift from energy-intensive sectors

to low-carbon ones will undoubtedly be necessary.

However, given that South Korea is the global leader

in shipbuilding and is the fifth-largest steel and auto

producer and that heavy industry accounts for 30

percent of overall GDP, reaching reductions targets

will be no easy feat.

Cost of Rapid Development

Since the de facto end of the Korean War in 1953, the

ROK has pursued an enthusiastic postwar reconstruc-

tion effort focused on industrialization, urbanization,

and export-driven economic growth. Over a relatively

FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS AND MARKETSFOCUS ON GREEN GROWTH 27

ing environmental groups were severely repressed,

seen as antigovernment, and often targeted as leftist

agitators. The constant state of postwar alert led the

ROK to clamp down tightly on groups considered,

if even remotely, to be associated with leftist forces.

Concerned with protecting their image and obsessed

with growth, authoritarian governments even went so

far as to discount development-related environmental

disasters.

6

A monument in Ulsan, a fishing village

turned industrial mecca in the late 1960s, is inscribed

with the following Park Chung-hee quotation, which

captures the zeitgeist of the developmental state:

Black, dark smoke rising from factories show promise

that our nation will prosper.

eventually began to compel the government to take

more environmentally conscious action. In 1990, more

than 20,000 citizens protested successfully against a

leaked government plan to construct a nuclear waste

disposal facility on Anmyeon-do, an island off of the

peninsulas west coast.

With environmental concerns increasingly becoming

a part of the public consciousness, during the 1980s

and 1990s the ROK government began the steady

introduction of new domestic environmental laws and

the strengthening of existing laws. ROK presidents also

began joining international agreements, such as the Vi-

enna Convention for the Protection of the Ozone Layer,

the Montreal Protocol on Substances That Deplete the

Ozone Layer, and the United Nations Framework Con-

vention on Climate Change, to name a few.

President Lee Myung-baks green growth strategy

is, however, the first time an ROK administration

has linked domestic economic growth policies with

environmental considerations. His approach rests

on the premise that significant, real reductions in

domestic greenhouse gas emissions need not curtail

the countrys economic growth; in fact, the strategy

proposes that investing in the development of new and

renewable energy sources can create jobs and spur

the economy while bringing the country closer to an

energy secure future. Given the countrys history of

sidelining and providing minimal budgetary support

for environmental issues, low carbon, green growth

is a welcome departure from development approaches

of the past.

Shades of Green

As the international community lauds the ROKs re-

cent efforts, hailing the country as a leader in the field

of green growth, local environmental groups have been

less than impressed. Critics argue that the national

policy misses the mark in terms of environmental

friendliness. Large-scale civil engineering projects

and the construction of nuclear power plantscorner-

stones of the green growth strategyhave provoked

debate over what truly qualifies as green.

6. To be sure, government ofcial attempts to cover up environmental crimes and disasters were not limited to postwar industri-

alization efforts. In 1991, eight Doosan plant ofcials dumped 325 tons of waste phenol, a substance known to cause cancer and

affect the nervous system, into the Nakdong River, the potable water source for roughly 10 million people. The plant ofcials were

arrested, as were seven government ofcials who tried to conceal the incident to protect the company.

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

Republic of Korea

High income: OECD

2

0

0

7

2

0

0

0

1

9

9

0

1

9

8

0

1

9

7

0

1

9

6

0

Figure 2: Carbon Dioxide Emissions in the

Republic of Korea and in OECD Countries,

19602007, metric tons per capita

Sources: World Development Indicators, World Development

Finance, World Bank, Washington, D.C., various years.

Metric tons per capita

Yet, as industrialization surged forward and envi-

ronmental impacts followed, citizen groups began

voicing concerns about deteriorating environmental,

ecological, and public healthrelated conditions ac-

companying major development projects. Emerging

alongside other social movement groups during the

era of democratization in the late 1980s and 1990s,

environmentalists started calling for better environ-

mental protections, including regulations on toxic

industrial waste and air pollution. Planned construc-

tion projects were challenged, and popular protests

28 THE KOREA ECONOMIC INSTITUTE

A central feature of the governments green growth

platform is the Four Rivers Restoration Project, a

massive river management scheme costing 22.2 trillion

won ($20 billion) or 8 percent of the ROKs annual

budget. By dredging and damming four major rivers,

the government hopes to increase the freshwater sup-

ply, improve water quality, and stave off flood risks.

Ecologists have noted that dredging 570 million cubic

meters, constructing 22 large weirs and 16 new dams,

and lining 151 miles of riverbank with concrete will

merely lead to tremendous ecosystem degradation.

Studies show that the natural habitats of riverine spe-

cies and 50-some different types of migratory birds

will be eroded, and restricting the natural course of

rivers goes against widely accepted environmental

policies that protect river health. Many South Kore-

ans also believe that the planning process has been

undemocratic, with few public hearings, hastily con-

ducted environmental impact assessment reports, and

a dismissive government attitude toward the concerns

raised by citizens and environmental interest groups.

Public opinion polls conducted since 2008, when the

project was first announced, have consistently shown

that a large majority of South Koreans, as high as 70

percent, oppose the project.

7

The governments green growth plan also entails heavy

investment in nuclear power, a low-carbon energy

source not always regarded by critics as green, given

its associated environmental disadvantages. Seoul has

targeted a doubling of nuclear energy consumption

by 2030, from 29 percent of total national electric-

ity-generating capacity to 59 percent, driven by the

construction of 10 nuclear plants alongside 7 that are

currently being built and 21 already in operation. The

country has also become a major nuclear technology

exporter, securing in December 2009 a $20 billion

contract to develop civil nuclear power plants in the

United Arab Emirates. The increasing use of nuclear

energy and the concomitant production of nuclear

waste have distressed South Koreans. Especially given

the recent disaster at the Fukushima Daiichi plant in

Japan, concerns about the safety of handling, process-

ing, and storing spent nuclear fuel and the placement

of nuclear power plants and waste disposal facilities

have come to the fore.

Greening the Marketplace

Environmental groups in South Korea have, however,

given their stamp of approval to other aspects of the

governments Green New Deal. Seoul has devel-

oped stricter building insulation and energy efficiency

standards, and South Korean firms have mastered the

production of advanced light-emitting diodes (LEDs),

a low-energy technology that is to replace incandescent

light bulbs, which will be banned by the end of 2013.

The introduction of energy conservation campaigns,

advancement of renewable energy sources, and devel-

opment of low-carbon technologies have been greeted

by the green community enthusiastically.

The ROK has also developed a plan to fully integrate

a smart grid system by 2030 in an effort to reduce

carbon emissions and increase efficiency in energy

distribution. The smart grid will apply two-way com-

munication technology between consumers and sup-

pliers on the nations current power-transmission grid,

allowing for an interactive exchange of real-time usage

and price data. Through enhanced monitoring, the

government hopes to optimize energy efficiency and

provide consumers with cost incentives to reduce use.

The smart grid will also support power feed-in from

renewable energy sources, such as solar panels at the

consumer end, helping to facilitate the increased sup-

ply and use of cleaner energy. Smart grid technology is

projected to decrease national electricity consumption

by 6 percent and national greenhouse gas emissions by

4.6 percent. In November 2010, 600 households were

connected to a smart grid pilot project on Jeju-do, an

island off of the southern end of the peninsula, with

plans to connect up to 6,000 households by 2013.

With smart grid development efforts taking shape in

the United States, Seoul and Washington have focused

on establishing partnerships between the public and

private sectors to develop, test, and implement smart

grid technologies. In April 2009, the U.S. Department

of Energy and the Korean Ministry of Knowledge

Economy (MKE) signed a statement committing to

collaborate on expanding and promoting smart grid

related research and development. The agreement also

expressed a desire to enhance bilateral cooperation

7. Four-River Project, Korea Herald, 13 December 2008; Rein in the Rivers Project, Yonhap, 2 October 2009; Marcia

McNally, Koreas Grand Plan: Dams and Canals to Restore Ecosystems, World Rivers Review 24, no. 3 (2009); Je-hae Do,

Foreign NGOs Brings 4-Rivers Plan Positive Spin, Korea Times, 9 February 2010.

FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS AND MARKETSFOCUS ON GREEN GROWTH 29

between universities, research institutes, and private

sector companies. Since then, MKE and the Illinois

Department of Commerce signed a memorandum of

understanding in January 2010, pledging to develop

and deploy commercially viable technologies in Il-

linois and the ROK. In February 2011, South Koreas

state-owned power company, the Korea Electric Power

Corporation, joined IBMs Global Intelligent Utility

Network Coalition, signaling the countrys intent to

promote smart grid technology adoption worldwide.

The ROK is also leading the charge to develop ad-

vanced lithium-ion batteries, the foundation of electric

cars. The Ministry of Educational Science and Tech-

nology recently launched the Battery 2020 Project,

aiming to build research and development capabilities

and pool private sector funds to gain a foothold in this

market. LG Chem, the leading South Korean chemi-

cals maker, recently cut the ribbon on the worlds larg-

est plant in Ochang, South Korea, which is reportedly

equipped to produce lithium-ion batteries for 100,000

vehicles annually. The United States and the ROK have

also partnered to drive an electric vehicle revolution.

With U.S. president Barack Obama pledging to roll out

1 million U.S.-made hybrid vehicles onto American

roads by 2015, General Motors selected LG Chem to

be its primary supplier of lithium-ion cells for GMs

Chevrolet Volt. The Chevy Volt is a plug-in hybrid

electric vehicle (HEV) with an extended range that

can drive up to 40 miles in battery-electric mode. LG

Chem also broke ground last summer on a Michigan-

based facility to produce batteries for other HEVs

in the United States, prompting a visit by President

Obama to welcome the battery plant and cementing a

new dimension to the ROK-U.S. alliance.

One of the countrys most promising programs to curb

greenhouse gas emissions is the carbon-trading system

envisioned in the Framework Act on Low-Carbon

Green Growth. Recently, however, the initiative suf-

fered a setback. In March, the MKE, backed by the

Federation of Korean Industries, succeeded in delaying

implementation of the ROKs carbon emission trad-

ing system to 2015, over the objections of the Blue

House Commission on Green Growth. The delay will

severely restrict the governments ability to meet its

midterm greenhouse gas reduction target of 4 percent

below 2005 levels by 2020. Industry leaders justified

the delay in a statement issued at the end of February,

noting that implementation would reduce their com-

petitiveness since other countriesnamely the United

States, China, India, and Japanhave postponed or

withdrawn country-specific carbon-trading schemes.

A Global Green Economic Future

At the international level, the ROK has played an

increasingly important role in advancing global agree-

ments. The country was instrumental in the adoption

by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and

Development (OECD) of the Declaration on Green

Growth, and an ROK proposala registry for de-

veloping countries to inscribe their climate change

mitigation activitiesbecame a key component of the

Copenhagen Accord developed at the United Nations

Framework Convention Conference of the Parties

in December 2009. With the ROKs emergence as

an important aid donor, Seoul has issued no- to low-

interest loans to fund green projects overseas, most

recently $35 million to Mozambique to support solar

power plants and $600 million to Indonesia to finance

development efforts that will include green industry.

South Korea and Denmark also signed a Green Growth

Alliance in May 2011 to reinforce cooperation between

government agencies, universities, and the private

sector from both countries.

In the longer term, the ROK has also established

the Global Green Growth Institute (GGGI), a global

nonprofit think tank dedicated to promoting economic

growth in environmentally sustainable ways. Link-

ing advanced nations, developing countries, leading

scientists, and climate change experts, the GGGI al-

lows for best-practice sharing and capacity building

to address environmental problems and offer support

to global green growth efforts. Headed by Richard

Samans, a former White House official during the

Clinton administration and former managing director

of the World Economic Forum, the GGGI currently

oversees several projects with partner countries and,

most recently, arranged to send experts to the United

Arab Emirates to help establish low-carbon green

growth strategies. The GGGI is also scheduled to open

an office in Abu Dhabi to act as a hub for the Middle

East and North Africa.

The Miracle on the Han seems to be paving the way

toward a global green economic future, offering the

international community guidance on green growth.

Certainly, a renewed focus on the environment is nec-

30 THE KOREA ECONOMIC INSTITUTE

essary as temperatures continue to rise, weather condi-

tions remain extreme, ecosystems become increasingly

threatened, and pollution presents a serious public

health risk. In this regard, the ROK has demonstrated

remarkable leadership by throwing its financial muscle

behind green efforts, setting ambitious greenhouse

gas emissions reductions targets and other commend-

able national goals. It remains debatable, however, if

other efforts like the Four Rivers Restoration Project

and the expansion of nuclear energy use promotes

sustainable green development. In hoping to mini-

mize environmental impacts without compromising

economic growth, Seoul may choose to consider a

more developed renewable energy industry rather than

megascale power-generating projects or additional

demand-side management strategies and other energy

conservation measures. Implementing the proposed

carbon-trading scheme would also have a significant

impact, but Seoul will need to stand firm in the face of

business and industry pressure to delay the initiative.

Indeed, with environmental externalities in even the

most well-intentioned of development plans, the jury

is still out on whether the excitement surrounding the

governments low carbon, green growth vision will

yield environmentally sustainable results.

Haeyoung Kim is an Environment and Science Ofcer

in the Ofce of Korean Affairs, Bureau of East Asia

and Pacic Affairs in the U.S. Department of State.

The views expressed in this article are those of the

author and do not necessarily reect those of the U.S.

Department of State or the U.S. government.

Korea Economic Institute

1800 K Street, N.W

Suite 1010

Washington D.C., 20006

Additional Commentary and Analysis

Korea: Economic Prospects and Challenges after the

Global Recession

Achievements in Seoul and Koreas Role in the G-20

Africa and South Koreas Leadership of the G-20

Koreas Green Growth Strategy: A Washington Perspective

An Ocean in Trouble, An Ocean of Opportunity

System Architecture for Effective Green Finance in Korea

Economic Implications for South Korea of the Current

Transformation in the Middle East

Korea-Africa: Emerging Opportunities

U.S.-Korea Economic Relations: A View from Seoul

A New Phase in ChinaNorth Korea Relations

Increasing Dependency: North Koreas Economic Relations

with China

The Economics of Reunification

Human Resources and Korean Reunification

Korea-China Economic Partnership: The Third China Rush

Selected Commentary

Korea and the World Economy

C. Fred Bergsten, Peterson Institute for International Economics

Koreas Challenges and Opportunities in 2011

Chae Wook, Korea Institute for International Economic Policy

A Reflection on the Seoul Summit

Paul Volcker, Former Chairman of the Federal Reserve

The G-20: Achievements and Challenges

SaKong Il, Korea International Trade Association

Korean Green Growth in a Global Context

Han Seung-soo, Global Green Growth Institute

Koreas Green Energy Policies and Prospects

Whang Jooho, Korea Institute of Energy Research

30848_Cover_Assembled-R1.indd 1 7/13/11 6:40 PM

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Ohio - 12Document2 pagesOhio - 12Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)No ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Ohio - 6Document2 pagesOhio - 6Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)No ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Ohio - 10Document2 pagesOhio - 10Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)No ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Oregon - 5Document2 pagesOregon - 5Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)No ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Ohio - 7Document2 pagesOhio - 7Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)No ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Florida - 25Document2 pagesFlorida - 25Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)No ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Ohio - 1Document2 pagesOhio - 1Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)No ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Top TX-17th Export of Goods To Korea in 2016Document2 pagesTop TX-17th Export of Goods To Korea in 2016Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)No ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Ohio - 4Document2 pagesOhio - 4Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)No ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Tennessee - 7Document2 pagesTennessee - 7Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)No ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Top CA-34th Export of Goods To Korea in 2016Document2 pagesTop CA-34th Export of Goods To Korea in 2016Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)No ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Top CA-13th Export of Goods To Korea in 2016Document2 pagesTop CA-13th Export of Goods To Korea in 2016Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)No ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Connecticut - 1Document2 pagesConnecticut - 1Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)No ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Texas - 35 - UpdatedDocument2 pagesTexas - 35 - UpdatedKorea Economic Institute of America (KEI)No ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Maryland - 6Document2 pagesMaryland - 6Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)No ratings yet

- Top TX-19th Export of Goods To Korea in 2016Document2 pagesTop TX-19th Export of Goods To Korea in 2016Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)No ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Top TX-30th Export of Goods To Korea in 2016Document2 pagesTop TX-30th Export of Goods To Korea in 2016Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)No ratings yet

- Georgia - 9Document2 pagesGeorgia - 9Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)No ratings yet

- Utah - 2Document2 pagesUtah - 2Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)No ratings yet

- Oregon - 4Document2 pagesOregon - 4Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)No ratings yet

- Arizona - 3Document2 pagesArizona - 3Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)No ratings yet

- North Carolina - 1Document2 pagesNorth Carolina - 1Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)No ratings yet

- Utah - 3Document2 pagesUtah - 3Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)No ratings yet

- Top FL-17th Export of Goods To Korea in 2016Document2 pagesTop FL-17th Export of Goods To Korea in 2016Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)No ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Washington - 1Document2 pagesWashington - 1Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)No ratings yet

- Top AL-4th Export of Goods To Korea in 2016Document2 pagesTop AL-4th Export of Goods To Korea in 2016Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)No ratings yet

- Top AR-3rd Export of Goods To Korea in 2016Document2 pagesTop AR-3rd Export of Goods To Korea in 2016Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)No ratings yet

- Florida - 2Document2 pagesFlorida - 2Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)No ratings yet

- Florida - 14Document2 pagesFlorida - 14Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)No ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Top OH-9th Export of Goods To Korea in 2016Document2 pagesTop OH-9th Export of Goods To Korea in 2016Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)No ratings yet

- Marinediesels - Co.uk - Members Section Engine Operation The Sulzer RTA Fuel PumpDocument2 pagesMarinediesels - Co.uk - Members Section Engine Operation The Sulzer RTA Fuel PumpArun SNo ratings yet

- 华为逆变器SUN2000-8 - 10 - 12 - 15 - 17 - 20KTL - IEC61727 认证 PDFDocument3 pages华为逆变器SUN2000-8 - 10 - 12 - 15 - 17 - 20KTL - IEC61727 认证 PDFSalam Adil KhudhairNo ratings yet

- Cep DerDocument4 pagesCep DerarshadNo ratings yet

- Brochure 5Document11 pagesBrochure 5Amgad AlsisiNo ratings yet

- Heliarc 281i/283i/353i AC/DCDocument6 pagesHeliarc 281i/283i/353i AC/DCnetineersNo ratings yet

- Answers Chart Plants Act 3Document1 pageAnswers Chart Plants Act 3api-279490884No ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Catalog-EQ - Kingsbury BearingDocument42 pagesCatalog-EQ - Kingsbury BearingZohaib AnserNo ratings yet

- Single PhasingDocument6 pagesSingle PhasingQuek Swee XianNo ratings yet

- Asia Clean Tech Report May 2010Document348 pagesAsia Clean Tech Report May 2010fdeadalusNo ratings yet

- Training ManualDocument551 pagesTraining ManualSeif Charaf100% (3)

- Chapter 1 Page 1: Why Electrical Energy ? or Importance of Electrical Energy. Generation of Electrical EnergyDocument1 pageChapter 1 Page 1: Why Electrical Energy ? or Importance of Electrical Energy. Generation of Electrical EnergyEngr Saud Shah BalochNo ratings yet

- Alternating Current (AC) vs. Direct Current (DC) - SFDocument9 pagesAlternating Current (AC) vs. Direct Current (DC) - SFSelvanNo ratings yet

- Concentrator Photovoltaic (C3PV) SystemDocument2 pagesConcentrator Photovoltaic (C3PV) SystemAdam JensenNo ratings yet

- Exercise ProblemsDocument1 pageExercise Problemsian heniel100% (1)

- Bill 565 000149029460 201108Document1 pageBill 565 000149029460 201108manojra_joshi453171No ratings yet

- The Boiler DesignDocument154 pagesThe Boiler DesignAyman Esa100% (2)

- 01 - Luzon GridDocument4 pages01 - Luzon Gridmommy uwuNo ratings yet

- Automotive World Move PlasticsDocument24 pagesAutomotive World Move PlasticsFERNANDO JOSE NOVAES100% (1)

- Wind Power Part 5Document26 pagesWind Power Part 5ttNo ratings yet

- 38AEDocument6 pages38AERim RimpingNo ratings yet

- Claudel 1986Document15 pagesClaudel 1986majesty9No ratings yet

- FormulasDocument9 pagesFormulasShankar JhaNo ratings yet

- 2007 MBE900 SpecsDocument2 pages2007 MBE900 SpecsGerson AquinoNo ratings yet

- Srne ml4860Document13 pagesSrne ml4860TonyNo ratings yet

- Ismr Technology Transfer Seminar: ANFO & Emulsion Characteristics Heavy Blends As A Tool For Blasters!Document29 pagesIsmr Technology Transfer Seminar: ANFO & Emulsion Characteristics Heavy Blends As A Tool For Blasters!Basilio DavilaNo ratings yet

- Engine Brake Design and Function in OlvoDocument9 pagesEngine Brake Design and Function in OlvoMohan PreethNo ratings yet

- A Guide To Solar PV SystemsDocument24 pagesA Guide To Solar PV Systemserkamlakar2234100% (1)

- FYP Presentation Slide Joshua 1131122826 3Document41 pagesFYP Presentation Slide Joshua 1131122826 3Joshua Chong100% (1)

- 8 65 105 EvapsDocument41 pages8 65 105 EvapsRestino KionyNo ratings yet

- University of San Agustin: Chemical Engineering DepartmentDocument43 pagesUniversity of San Agustin: Chemical Engineering DepartmentReynee Shaira Lamprea MatulacNo ratings yet

- Prisoners of Geography: Ten Maps That Explain Everything About the WorldFrom EverandPrisoners of Geography: Ten Maps That Explain Everything About the WorldRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1147)

- Reagan at Reykjavik: Forty-Eight Hours That Ended the Cold WarFrom EverandReagan at Reykjavik: Forty-Eight Hours That Ended the Cold WarRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- How States Think: The Rationality of Foreign PolicyFrom EverandHow States Think: The Rationality of Foreign PolicyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (7)

- Son of Hamas: A Gripping Account of Terror, Betrayal, Political Intrigue, and Unthinkable ChoicesFrom EverandSon of Hamas: A Gripping Account of Terror, Betrayal, Political Intrigue, and Unthinkable ChoicesRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (504)

- Age of Revolutions: Progress and Backlash from 1600 to the PresentFrom EverandAge of Revolutions: Progress and Backlash from 1600 to the PresentRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (8)

- The Tragic Mind: Fear, Fate, and the Burden of PowerFrom EverandThe Tragic Mind: Fear, Fate, and the Burden of PowerRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (14)

- The Future of Geography: How the Competition in Space Will Change Our WorldFrom EverandThe Future of Geography: How the Competition in Space Will Change Our WorldRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (6)

- Chip War: The Fight for the World's Most Critical TechnologyFrom EverandChip War: The Fight for the World's Most Critical TechnologyRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (82)

- The Shadow War: Inside Russia's and China's Secret Operations to Defeat AmericaFrom EverandThe Shadow War: Inside Russia's and China's Secret Operations to Defeat AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (12)