Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Satish Chandra Sarkar Vs Emperor On 15 January-1

Uploaded by

Alex WolfersOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Satish Chandra Sarkar Vs Emperor On 15 January-1

Uploaded by

Alex WolfersCopyright:

Available Formats

Satish Chandra Sarkar vs Emperor on 15 January, 1912

Calcutta High Court Satish Chandra Sarkar vs Emperor on 15 January, 1912 Equivalent citations: (1912) ILR 39 Cal 456 Author: H A Sharfuddin Bench: Holmwood, Sharfuddin JUDGMENT Holmwood and Sharfuddin, JJ. 1. This Rule was issued calling upon the District Magistrate of Rajshahi to show cause why the order directing the petitioner to execute a bond for Rs. 500, with two sureties of Rs. 500 each, for his good behaviour for one year, under Section 109 of the Criminal Procedure Code, and on failure to give security to undergo rigorous imprisonment for one year, should not be set aside on the ground that it does not appear that the petitioner is without ostensible means of subsistence, and that the account he has given of himself is satisfactory. Having given the case our most attentive consideration, we are of opinion that the Rule must be made absolute. The proceeding upon which the order complained of was based was dated the 12th August 1911, and set out that, whereas it was reported that Satish Chandra Sarkar was in Nattore or its vicinity, and was concealing himself in order to avoid observation, and there was reason to believe that he was connected with anarchist agitation and conspiracies for the purpose of committing dacoity and other crimes, and whereas he had no ostensible means of livelihood, and could not give a satisfactory account of himself, he was called upon to execute securities as set out above. 2. The proceedings were taken under Section 109 of the Criminal Procedure Code, and not under Section 110, and the ground covered was, on the face of it, in respect of both Clauses (a) and (b) of the Section. The officiating District Magistrate, however, dealt with it under three heads, the first being that the accused was concealing himself in order to avoid observation. This, of course, is no offence at all, and the Magistrate held, as he was bound to hold, that the prosecution had not made out its case on this head. But he omitted to notice that what he calls the second allegation against the accused is really a substantive and necessary part of the first, if there is to be any order under Clause (a) of Section 109. 2. The whole clause must be read together, and the, object of the concealment must be with a view to committing some offence. 3. Now, the second allegation is that the accused is connected with anarchist agitation and conspiracies for the purpose of committing dacoity and other crimes. This standing by itself could constitute no ground for a proceeding under Section 109, but would properly form the basis of a proceeding under Section 110, to which the accused has had no opportunity of answering. It being found that he only returned to his father's house on the 9th of August, and merely secluded himself in the day-time, going out at night for exercise, and that the prosecution had not made out that lie was taking any particular steps to conceal himself for the purpose of committing any offence, the fact that he had previously been connected with any criminal conspiracy or might still be in correspondence with any criminals outside the jurisdiction, would not be relevant in a case under Section 109. It would have to form the basis of a substantive proceeding under Section 110. The connection between the alleged concealment and the accused's history having admittedly failed, the proceeding under Section 109(a) necessarily fails also. The District Magistrate may, of course, take any proceedings he is advised under Section 110, if he is of opinion that the accused is still a desperate and dangerous character, but he cannot be called upon to furnish any security in respect of an alleged temporary concealment in his father's house unconnected with any intention to commit an offence, nor with any previous concealment which admittedly but have been outside the jurisdiction. We come, therefore, to the consideration of the charge under Clause (b), which is that he has no ostensible means of livelihood, and that he cannot give a satisfactory account of himself. The learned Magistrate finds against him on both these points, although he finds that the accused is a member of a joint family, that he came straight to his father's house on his arrival in Nattore, and that his father and brother accompanied him to Court. He appears to expect that the father and brother should

Indian Kanoon - http://indiankanoon.org/doc/483432/ 1

Satish Chandra Sarkar vs Emperor on 15 January, 1912

go into the witness-box and take oath that he is being supported out of joint family funds. Obviously, as long as a young man out of employment is staying in his father's house, and that father is a man of substance, able, if necessary, to support him, he cannot be said to be without ostensible means of subsistence. The use of the word "livelihood" seems to have led the learned Magistrate into error. 3. We have no hesitation in finding that the accused's father is a very ostensible means of subsistence as long as lie keeps his son in his house, and that no further evidence is required. 4. As regards the account he is asked to give of himself, it would appear that the Magistrate has exceeded his jurisdiction under Section 109. The account he gives of his presence in the limits of the Magistrate's jurisdiction is quite satisfactory. He had fled from fear of a warrant directed against him in a specific case. That warrant having been withdrawn three months ago, he has ventured to return to his home, though he keeps himself, as is natural and we think proper, in strict seclusion from curious enquiries. 5. He cannot be called upon to give any account of his presence in any other jurisdiction, except by the Magistrate who is empowered to take proceedings in that jurisdiction. 6. The whole object of this part of the clause is to enable Magistrates to take action against suspicious strangers lurking within their jurisdiction. The greatest criminal in the world is not liable to be questioned as to his presence in his own home, unless there is some specific outstanding charge against him. 7. We, therefore, hold that the proceeding under Clause (b) of the Section also fails, and the proceedings in this case must be set aside and the accused discharged from his bail, subject to any action the District Magistrate may see fit to take under Section 110, but no such proceeding, we may point out, should be taken unless there is evidence that the petitioner is still connected with conspiracies to commit crime or is a desperate and dangerous character at the present time. 8. The Rule is made absolute, and the proceedings under Section 109 are set aside.

Indian Kanoon - http://indiankanoon.org/doc/483432/

You might also like

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- A ClarificationDocument1 pageA ClarificationAlex WolfersNo ratings yet

- Will Labour Lose in Stoke? - BushqDocument2 pagesWill Labour Lose in Stoke? - BushqAlex WolfersNo ratings yet

- "Capitalism and Desire - The Psychic Cost of Free Markets" - McGowan Reviewed - ZupancicDocument5 pages"Capitalism and Desire - The Psychic Cost of Free Markets" - McGowan Reviewed - ZupancicAlex WolfersNo ratings yet

- Consequences of Nationalism in IndiaDocument18 pagesConsequences of Nationalism in IndiaAlex WolfersNo ratings yet

- Corbyn's Team Planning for Victory Next TimeDocument4 pagesCorbyn's Team Planning for Victory Next TimeAlex WolfersNo ratings yet

- Paperback Edition of Cosmic Love and HumDocument1 pagePaperback Edition of Cosmic Love and HumAlex WolfersNo ratings yet

- The Calling of History: Sir Jadunath Sarkar and His Empire of Truth (Chicago, 2015)Document1 pageThe Calling of History: Sir Jadunath Sarkar and His Empire of Truth (Chicago, 2015)Alex WolfersNo ratings yet

- Labour and Immigration1Document14 pagesLabour and Immigration1Alex WolfersNo ratings yet

- Masculinity and Nationalism in Aurobindo's Perseus the DelivererDocument2 pagesMasculinity and Nationalism in Aurobindo's Perseus the DelivererAlex WolfersNo ratings yet

- Independence Day Rituals - ZachariahDocument1 pageIndependence Day Rituals - ZachariahAlex WolfersNo ratings yet

- Nav Jawan Bharat SabhaDocument20 pagesNav Jawan Bharat SabhasaturnitinerantNo ratings yet

- Vivekananda's Vision of Religious Unity in IndiaDocument2 pagesVivekananda's Vision of Religious Unity in IndiaAlex WolfersNo ratings yet

- Faith Tourism - For A Healthy Environment and A More Sensitive World - SharmaDocument10 pagesFaith Tourism - For A Healthy Environment and A More Sensitive World - SharmaAlex WolfersNo ratings yet

- Books - The Cult of Divine Power - "Shaki Sadhana" (Kundalini Yoga) - SinhaDocument145 pagesBooks - The Cult of Divine Power - "Shaki Sadhana" (Kundalini Yoga) - SinhaAlex Wolfers100% (1)

- Sacred JourneysDocument8 pagesSacred JourneysAlex WolfersNo ratings yet

- "The Chambir of My Thought" - Self and Conduct in An Early Islamic Ethical Treatise - KhanDocument22 pages"The Chambir of My Thought" - Self and Conduct in An Early Islamic Ethical Treatise - KhanAlex WolfersNo ratings yet

- Sacred SovereignDocument16 pagesSacred Sovereignlansmeys1498100% (1)

- Offering Flowers, Feeding Skulls - Popular Goddess Worship in West Bengal - Fruzetti ReviewDocument3 pagesOffering Flowers, Feeding Skulls - Popular Goddess Worship in West Bengal - Fruzetti ReviewAlex Wolfers100% (1)

- Meerut and A Hanging - "Young India," Popular Socialism, and The Dynamics of Imperialism - Zachariah and Roy1Document18 pagesMeerut and A Hanging - "Young India," Popular Socialism, and The Dynamics of Imperialism - Zachariah and Roy1Alex WolfersNo ratings yet

- Namdeo Dhasal - Poet and Panther - Hovell - OCRRINGDocument19 pagesNamdeo Dhasal - Poet and Panther - Hovell - OCRRINGAlex WolfersNo ratings yet

- Fin-De-Siecle - Once More With Feeling - LaqueurDocument43 pagesFin-De-Siecle - Once More With Feeling - LaqueurAlex WolfersNo ratings yet

- Candidasa - Singing The Glory of Lord Krishna - The Srikrsnakirtana - Stewart - OCRRINGDocument3 pagesCandidasa - Singing The Glory of Lord Krishna - The Srikrsnakirtana - Stewart - OCRRINGAlex WolfersNo ratings yet

- Offering Flowers, Feeding Skulls - Popular Goddess Worship in West Bengal - Fruzetti ReviewDocument3 pagesOffering Flowers, Feeding Skulls - Popular Goddess Worship in West Bengal - Fruzetti ReviewAlex Wolfers100% (1)

- Auro's Synthesis of Religion and PoliticsDocument10 pagesAuro's Synthesis of Religion and PoliticsAlex WolfersNo ratings yet

- Dangerous Liaisons: Desire and Limit in the Home and the WorldDocument13 pagesDangerous Liaisons: Desire and Limit in the Home and the WorldAlex WolfersNo ratings yet

- Of Yoginis and Tantriksters - DonigerDocument4 pagesOf Yoginis and Tantriksters - DonigerAlex Wolfers100% (1)

- Seven Part Kundalini Yoga Set Treats AddictionsDocument11 pagesSeven Part Kundalini Yoga Set Treats AddictionsAlex Wolfers100% (3)

- Ramthakur and Upen BanerjeeDocument4 pagesRamthakur and Upen BanerjeeAlex WolfersNo ratings yet

- Seven Part Kundalini Yoga Set Treats AddictionsDocument11 pagesSeven Part Kundalini Yoga Set Treats AddictionsAlex Wolfers100% (3)

- Unholy Alliances - MishraDocument13 pagesUnholy Alliances - MishraAlex WolfersNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Tierzah Mapson IndictmentDocument18 pagesTierzah Mapson IndictmentNational Content DeskNo ratings yet

- Recusal Brief FinalDocument57 pagesRecusal Brief Finalcaroldeehuneke50% (2)

- Public Prosecutor V Syahril Bin Razali (2014) 6 MLJ 881Document16 pagesPublic Prosecutor V Syahril Bin Razali (2014) 6 MLJ 881Irdina Zafirah AzaharNo ratings yet

- Leon County Booking Report: Jan. 10, 2021Document2 pagesLeon County Booking Report: Jan. 10, 2021WCTV Digital TeamNo ratings yet

- Clifton Christopher Crim HistoryDocument11 pagesClifton Christopher Crim HistoryAnonymous kprzCiZNo ratings yet

- Mass. SJC Reverses 2013 Murder Conviction of Curtis CombsDocument21 pagesMass. SJC Reverses 2013 Murder Conviction of Curtis CombsPatrick JohnsonNo ratings yet

- Munusamy v Public Prosecutor - Trafficking in cannabis caseDocument8 pagesMunusamy v Public Prosecutor - Trafficking in cannabis caseIda Zahidah ZakariaNo ratings yet

- Omongan Vs OmiponDocument2 pagesOmongan Vs OmiponTeoti Navarro ReyesNo ratings yet

- Theories of LawDocument3 pagesTheories of LawKnuckles Push UpNo ratings yet

- Philippine Court Jurisdiction Over Crimes Committed on Foreign ShipsDocument2 pagesPhilippine Court Jurisdiction Over Crimes Committed on Foreign ShipsCla BANo ratings yet

- Rosebud SIoux Tribe Criminal Offense CodeDocument5 pagesRosebud SIoux Tribe Criminal Offense CodeOjinjintka NewsNo ratings yet

- Rhetorical Analysis EssayDocument6 pagesRhetorical Analysis Essayapi-438629281No ratings yet

- Research Chapter 5 Group 7Document6 pagesResearch Chapter 5 Group 7Julie Rose DS BaldovinoNo ratings yet

- Batas Pambansa BLG 22Document3 pagesBatas Pambansa BLG 22Nikko SterlingNo ratings yet

- 2.23.17 Mahoney Malicious Prosecution OverturnedDocument9 pages2.23.17 Mahoney Malicious Prosecution OverturnedWatertown Daily TimesNo ratings yet

- PEOPLE V. BONOAN G.R. No. L-45130Document6 pagesPEOPLE V. BONOAN G.R. No. L-45130yanyan yuNo ratings yet

- ACLU Complaint and SummonsesDocument24 pagesACLU Complaint and SummonsesWGN Web Desk100% (1)

- People v. Legaspi Aggravating CircumstancesDocument2 pagesPeople v. Legaspi Aggravating Circumstancesjason caballero100% (1)

- People v. Mingoa 3Document1 pagePeople v. Mingoa 3Jp CoquiaNo ratings yet

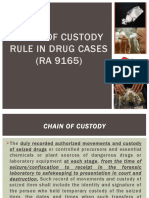

- Chain of Custody Rule in Drug Cases (RA 9165)Document23 pagesChain of Custody Rule in Drug Cases (RA 9165)Lexthom Balayanto100% (3)

- February 6, 2019 G.R. No. 221434 People of The Philippines, Appellee RESTBEI B. TAMPUS, AppellantDocument2 pagesFebruary 6, 2019 G.R. No. 221434 People of The Philippines, Appellee RESTBEI B. TAMPUS, AppellantRobNo ratings yet

- Final report on fatal shooting in Mlang, PhilippinesDocument2 pagesFinal report on fatal shooting in Mlang, PhilippinesApril Jay EgagamaoNo ratings yet

- DOCUMENTARY EVIDENCE Sison Vs PeopleDocument2 pagesDOCUMENTARY EVIDENCE Sison Vs PeopleAdi LimNo ratings yet

- People V CamatDocument2 pagesPeople V CamatRachel Leachon0% (1)

- Villareal vs. PeopleDocument84 pagesVillareal vs. PeopleJAMNo ratings yet

- Cdi3 - Specialized Crime Investigation Power Point Prelim Slides 1-40Document40 pagesCdi3 - Specialized Crime Investigation Power Point Prelim Slides 1-40Kent DomsNo ratings yet

- Plea Bargaining: An Instrument To Reduce The Burden of JudiciaryDocument9 pagesPlea Bargaining: An Instrument To Reduce The Burden of JudiciaryJai SoniNo ratings yet

- Alcatraz Island Prezentare PowerPoint EnglezaDocument8 pagesAlcatraz Island Prezentare PowerPoint EnglezaFlorian BăceanuNo ratings yet

- First Information Report)Document13 pagesFirst Information Report)uday m sannakkiNo ratings yet

- US v. Blankenship Sentencing MemoDocument16 pagesUS v. Blankenship Sentencing MemoStephen LoiaconiNo ratings yet