Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ways of Teaching Arabic Sajida AbuAli

Uploaded by

Muhammet GunaydinOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ways of Teaching Arabic Sajida AbuAli

Uploaded by

Muhammet GunaydinCopyright:

Available Formats

ISNA Education Forum 2008 March 21 23, 2008, Chicago, IL

Ways of Teaching Arabic through Story

Description of presenter My name is Sajida Abu Ali; I am a teacher at Al-Nour School and Al Iman weekend School in Cleveland Ohio. I graduated as a teacher in 1995 and have taught a variety of subjects. I currently teach Arabic and Quran. Masters Degree in modern languages (Curriculum and Instructional Design). CORE Program for Foreign Language (Arabic), 2006-2007and CRETE training, Summer 2007.

Abstract Storybooks offer important learning opportunities about narrative text. By listening to many stories, children begin to build an awareness of the ways stories are organized. Childrens concept of story gradually includes the notion that stories have characters that are sustained throughout the story and that stories have actions or events that lead up to an ending. In addition, through read aloud and shared readings with adults, children learn that a story has a setting where it takes place and conversations might be taking place between characters. Their growing awareness and understanding of stories is often demonstrated when they attempt to retell or re-enact events from their favorite story with the support of their peers. Childrens books and personal and shared experiences provide opportunities for early childhood educators to demonstrate and engage young children in the process of writing. Through small group discussion, or one-on-one dialogue, adults engage children through modeled and shared writing experiences where text is created, the relationship between the written and spoken word is modeled and the function and purpose of writing are illustrated. In foreign language thematic units are organized in terms of meaningful experiences with language, focused on a theme and on theme-related tasks. These

experiences prepare students to use the language for a variety of purposes-their own purposes-beyond the classroom.

The framework and the standards: The framework for Curriculum Development is fully compatible with the Standards for foreign language learning in the 21st Century. Each of the outcomes circles ties directly to one of the goals in the standards. Language in Use could also be named Communication, Culture and Cultures are fully compatible; and Subject Content could easily be renamed Connections. The remaining Standards, Comparisons, and Communities interact with the framework outcomes at several points, in the following diagrams standard 4.1 is illustrate which deals with comparing languages, and standard 4.2 addresses comparison of cultures. The communities goal brings the learning of language, culture, and curriculum content beyond the classroom, and engages the learner with the language and the culture for lifelong learning.

Statement of problem Thematic planning and instruction are among the most important elements of an effective early language program. Our standards orientation calls for integrated learning, with connections to other content areas and to new information through the use of the new language. Our growing insight about brain-compatible learning supports thematic instruction as well. As we teach new languages to children, our focus is making meaning, rather than making accurate new sounds or grammatically correct sentences (important though these may be). Eric Jensen (1998) suggests that for meaning-making to take place, we should evoke three important ingredients in our general practice: emotion, relevance, and context and patterns (96) A carefully designed theme can incorporate emotion, one of the most powerful channels for learning; relevance, a critical motivator for language learning; and rich context, an element that bring language learning to life and active the pattern making functions of the brain. Much of elementary school curriculum in all content areas is built around themes, often as a means of integrating several subjects during the school respond to the

intellectual, social, and developmental needs of the early adolescent learner. As the language teacher connects language instruction to existing themes of creates languagespecific themes, the language class is clearly an integrated part of the school day, and languages are perceived to be meaningful components of student learning.

Practical elements of implementation: 1. Thematic planning makes instruction more comprehensible, because the theme creates a meaningful context. In thematic unit, students can interpret new language and new information on the basis of their background knowledge. They are not just learning vocabulary in isolation; they are using words to identify which foods came from Middle East, or which animals are endangered in South America etc.

2. Thematic planning changes the instructional focus from the language itself to the use of language to achieve meaningful goals. In thematic instruction we focus on using the language to communicate something related to a theme, rather than repeating words in isolation with no connection to the classroom or the student. Instead of focusing on how to say or write something, thematic instruction shifts the focus to communicating a message for a reason. As we shift the focus to what language means and can do, students become motivated to acquire language and to be accurate, because they want to communicate about information that is of interest to them.

3. Thematic instruction provides a rich context for standards-based instruction. One of the important features of the National standards for foreign language learning is their emphasis on working toward a goal, and focusing on the big picture or the big idea. Many of the scenarios found in the Standards document are also examples of integrated thematic units.

4. Thematic instruction involves the students in real language use in a variety of situations, modes, and text types. Thematic instruction, especially when it is organized in a story structure, gives students the opportunity to use language in a variety of situations, including simulations of cultural experiences. A theme lends itself to all three of the communication modes: interpersonal, interpretive, and presentational. Text types within a thematic unit can range from preparing and reading poetry to reading headlines to creating or listening to a description to participating in a conversation to listening to a play-and the list goes on and on.

Methods A central goal during the early learning years is to enhance childrens exposure to concepts about print. These concepts are related to the visual characteristics, features and properties of written language. Some early childhood educators use Big Books to help children distinguish many book and print features, including the fact that a book must be held right side up to read the words and view the illustrations; that print, rather than pictures, carries the meaning of the story; that print conveys not just any message, but a specific message; that the strings of letters between spaces are words that correspond to an oral version; and that reading progresses from left to right and top to bottom. The process of gaining meaning from spoken language begins in infancy as young children search for meaning through the context, gestures and facial cues. Children demonstrate their understanding or comprehension by asking questions and making comments throughout the day. They bring this curiosity to reading events and develop comprehension skills through the conversation around the story by making predictions about story events or characters or commenting on the topic of a story being read to them. In addition, children take delight in retelling stories or acting out the events of a story in their play. Pausing at the end of a sentence to let children join in, asking open-ended questions and helping children make connections to prior experiences are all effective teaching strategies for developing comprehension skills. Concepts of Print

1. Understand that print has meaning by demonstrating the functions of print through play activities (e.g., orders from a menu in pretend play). 2. Hold books right side up, know that people read pages from front to back, top to bottom and read words from right to left. 3. Begin to distinguish print from pictures. Comprehension Strategies 4. Begin to visualize, represent, and sequence an understanding of text through a variety of media and play. 5. Predict what might happen next during reading of text. 6. Connect information or ideas in text to prior knowledge and experience (e.g., I have a new puppy at home too.). 7. Answer literal questions to demonstrate comprehension of orally read age-appropriate texts. Self-Monitoring Strategies 8. Respond to oral reading by commenting or questioning (e.g., That would taste yucky.). Independent Reading 9.Select favorite books and poems and participate in shared oral reading and discussions. Reading Applications 1. Use pictures and illustrations to aid comprehension (e.g., talks about picture when sharing a story in a book). 2. Retell information from informational text. 3. Tell the topic of a selection that has been read aloud (e.g., What is the book about?). 4. Gain text information from pictures, photos, simple charts and labels. 5. Follow simple directions. 6. Focus on curriculum and learners with different instructional strategies. 7. Seek for greater collaboration between content areas.

Recommendations of practical implementation

Children learn that books contain different kinds of information books that provide facts about a topic; books that help us understand general ideas or themes, such as numbers and the alphabet; books that tell us stories about real people and events and those that share fairy tales and make believe, such as The very Hungry Caterpillar. Through multiple, varied and engaging experiences, children develop concepts about these texts, how they are organized and how they are useful tools in learning about the world. Young children need to chew on books, hug them, laugh at them, touch and feel them, and associate them with a warm voice and an interested adult. Betsy Harne Careful planning can help the early language teacher to make the most of the limited time available for instruction in the target language. One meaningful approach to planning curriculum is the development of integrated thematic units that incorporate the key elements of language-in-use, subject content, and culture. Effective planning takes into account the educational development of the students and draws on such approaches as story form and backward design to make learning more meaningful and more memorable. The careful preparation of student-oriented objectives and a written plan can free the teacher to be flexible as they develop without losing the direction and focus of the lesson. Each plan should be organized around the needs and development of the whole child and take into account the childs need for both variety and routine. References Egan, Kieran. Teaching as Story Telling. Chicago: Univrsity of Chicago Press, 1986. Glastonbury (CT) public Schools Foreign Language Curriculum Documents. Available on-line at http://foreignlanguage.org/curriculum/ Sandrock, Paul. Planning Curriculum for learning World Languages. Madison, WI: Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction, 2002. Birckbichler, Diane W., ed. Reflecting on the past to Shape the future. The ACTEL Foreign Language Education Series. Lincolnwood, IL: National Textbook Company, 2000. http://ode.state.oh.us/GD/Templates/Pages/ODE/ODEPrimary.aspx?page=2&TopicRelati onID=312

You might also like

- The Four Pronged Approach, EDUC 13 Report...Document22 pagesThe Four Pronged Approach, EDUC 13 Report...Dhon CalloNo ratings yet

- Issues Around Theme-Based Teaching: C 8: T - B T LDocument4 pagesIssues Around Theme-Based Teaching: C 8: T - B T LMelisa ParodiNo ratings yet

- Literacy Development in Early ChildhoodDocument75 pagesLiteracy Development in Early ChildhoodbaphometAhmetNo ratings yet

- Saunders Content and Pedagogy Ela Literacy 3Document5 pagesSaunders Content and Pedagogy Ela Literacy 3api-614176439No ratings yet

- Assessment For Learning - EditedDocument15 pagesAssessment For Learning - EditeddrukibsNo ratings yet

- Paper EYL Kelompok 6 JadiDocument25 pagesPaper EYL Kelompok 6 JadiSayyidah BalqiesNo ratings yet

- Developing Speaking Skills Through Fairy f251f377Document5 pagesDeveloping Speaking Skills Through Fairy f251f377Вікторія ДавидюкNo ratings yet

- Edición Currículo Primaria-1Document203 pagesEdición Currículo Primaria-1mikemaia82No ratings yet

- LESSON 2 WPS OfficeDocument7 pagesLESSON 2 WPS OfficeGrald Traifalgar Patrick ShawNo ratings yet

- Make Them Think! Using Literature in The Primary English Language Classroom To Develop Critical Thinking SkillsDocument11 pagesMake Them Think! Using Literature in The Primary English Language Classroom To Develop Critical Thinking SkillsEugeneNo ratings yet

- Curiculo de Inglés - Subnivel Medio.Document80 pagesCuriculo de Inglés - Subnivel Medio.Tania Giomara Godoy QuisirumbayNo ratings yet

- EE102 Learning MaterialsDocument37 pagesEE102 Learning MaterialsAlexis AlmadronesNo ratings yet

- Play Reading in Vocabulary AcquisitionDocument7 pagesPlay Reading in Vocabulary AcquisitionRemigio EskandorNo ratings yet

- Notes On Literacy and EnglishDocument10 pagesNotes On Literacy and EnglishKailee DebirredNo ratings yet

- Stages of Literacy DevelopmentDocument3 pagesStages of Literacy DevelopmentSEAN BENEDICT PERNESNo ratings yet

- UNIT 2prof Ed10Document17 pagesUNIT 2prof Ed10Shieva RevamonteNo ratings yet

- Effective CommunicationDocument8 pagesEffective CommunicationNoviade JusmanNo ratings yet

- Teaching Strategies in MTB 1Document6 pagesTeaching Strategies in MTB 1HASLY NECOLE HASLY LAREZANo ratings yet

- Teach Your 4 Year Old To Read: Pre Kindergarten Literacy Tips and TricksFrom EverandTeach Your 4 Year Old To Read: Pre Kindergarten Literacy Tips and TricksNo ratings yet

- Novita Sari 6C - Summary TEFL 8Document5 pagesNovita Sari 6C - Summary TEFL 8Novita SariNo ratings yet

- The Early Literacy Handbook: Making sense of language and literacy with children birth to seven - a practical guide to the context approachFrom EverandThe Early Literacy Handbook: Making sense of language and literacy with children birth to seven - a practical guide to the context approachRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Theories On Reading AcquisitionDocument2 pagesTheories On Reading AcquisitionRonnel Manilag AtienzaNo ratings yet

- Theories of Reading AcquisitionDocument10 pagesTheories of Reading AcquisitionRicca Piadozo Velasquez0% (1)

- ISL Tajuk 5 Listening SkillsDocument2 pagesISL Tajuk 5 Listening SkillsgmailNo ratings yet

- Directed Learning ExperienceDocument13 pagesDirected Learning Experienceapi-340409501No ratings yet

- Teaching of Speaking, Listening and Reading Reviewer MajorshipDocument21 pagesTeaching of Speaking, Listening and Reading Reviewer MajorshipalexaNo ratings yet

- Skip To Main ContentDocument24 pagesSkip To Main ContentMohamed El Bachir ThiamNo ratings yet

- Wood Ela Framing StatementDocument6 pagesWood Ela Framing Statementapi-510456312No ratings yet

- Accountability To The ChildDocument9 pagesAccountability To The ChildDragana KasipovicNo ratings yet

- Didáctica Específica 1 InglesDocument30 pagesDidáctica Específica 1 InglesLaVendetta MiaNo ratings yet

- Disciplinary Literacy PaperDocument7 pagesDisciplinary Literacy Paperapi-533837687No ratings yet

- Chapter 10 & 11Document6 pagesChapter 10 & 11DAMILOLA OLATUNDENo ratings yet

- An Integrated Approach For The Development of Communication SkillsDocument3 pagesAn Integrated Approach For The Development of Communication SkillseLockNo ratings yet

- Finals Module Teaching English in The ElemDocument55 pagesFinals Module Teaching English in The ElemHaifa dulayNo ratings yet

- Tema 07 Opisición Inglés SecundariaDocument6 pagesTema 07 Opisición Inglés SecundariadroiartzunNo ratings yet

- Effective Technique For EnglishDocument7 pagesEffective Technique For EnglishanknduttyNo ratings yet

- Final 4 Pronged ApproachDocument17 pagesFinal 4 Pronged ApproachmasorNo ratings yet

- Edu 512 Tompkins Chapter 1-12 NotesDocument12 pagesEdu 512 Tompkins Chapter 1-12 Notesapi-438371615100% (2)

- #2 Canale and SwainDocument5 pages#2 Canale and SwainKRISTELLE COMBATERNo ratings yet

- Action Research Edited Final - 2nd PartDocument90 pagesAction Research Edited Final - 2nd PartJulie Anne Lobrido Carmona100% (1)

- Development of 21st Century LiteraciesDocument5 pagesDevelopment of 21st Century LiteraciesMARC MENORCANo ratings yet

- RMK Study Language ArtsDocument5 pagesRMK Study Language ArtsIzzati AzmanNo ratings yet

- 4.teaching Reading and WritingDocument10 pages4.teaching Reading and WritingPio MelAncolico Jr.No ratings yet

- PedagogyDocument8 pagesPedagogyHimaniNo ratings yet

- Bem 111 Kate Mirabueno Beed3cDocument3 pagesBem 111 Kate Mirabueno Beed3cKate MirabuenoNo ratings yet

- Module 3. A Brief History of Language Teaching 2Document10 pagesModule 3. A Brief History of Language Teaching 2Memy Muresan100% (1)

- Chapter 2 3 TompDocument3 pagesChapter 2 3 Tompapi-393055116No ratings yet

- Motivating Students To Read: LiteratureDocument6 pagesMotivating Students To Read: LiteratureZouhir KasmiNo ratings yet

- Shaping Paper - Reading 2023-05-04Document7 pagesShaping Paper - Reading 2023-05-04Tristan PiosangNo ratings yet

- 4 Pronged ApproachDocument29 pages4 Pronged ApproachmasorNo ratings yet

- Brief of Lectures of Teachhing English For YoungDocument15 pagesBrief of Lectures of Teachhing English For YoungRio RioNo ratings yet

- A Functional Approach To LanguageDocument7 pagesA Functional Approach To Languageカアンドレス100% (1)

- совв мет 1-50 (копия)Document45 pagesсовв мет 1-50 (копия)AknietNo ratings yet

- Trabalho Ingles para CriançasDocument2 pagesTrabalho Ingles para CriançassusanabettuNo ratings yet

- Criteria For The Selection of Stories (NOTES)Document4 pagesCriteria For The Selection of Stories (NOTES)Lee Ming YeoNo ratings yet

- Teaching English To Young Learners ThesisDocument8 pagesTeaching English To Young Learners Thesissarahdavisjackson100% (2)

- 1852 VocabularyDocument13 pages1852 VocabularyKasthuri SuppiahNo ratings yet

- Language Curriculum and MaterialsDevelopment Workshop For PrimarySchool English Teachers of Brunei Darussalam - Session 4Document42 pagesLanguage Curriculum and MaterialsDevelopment Workshop For PrimarySchool English Teachers of Brunei Darussalam - Session 4Teacher2905No ratings yet

- Understanding Reading Comprehension:1: What IsDocument8 pagesUnderstanding Reading Comprehension:1: What IsArasu RajendranNo ratings yet

- Understanding Memor: Eeach. at A Be A.caDocument15 pagesUnderstanding Memor: Eeach. at A Be A.camboscNo ratings yet

- Khilafat e Rashida - The Benevolent and Futuristic Model of Governance For HumanityDocument271 pagesKhilafat e Rashida - The Benevolent and Futuristic Model of Governance For HumanityBTghazwa100% (13)

- Really Great Reading Kindergarten Foundational Skills Survey RGRFSSK112320Document83 pagesReally Great Reading Kindergarten Foundational Skills Survey RGRFSSK112320JM and AlyNo ratings yet

- Object-Oriented Database Development Using Db4oDocument67 pagesObject-Oriented Database Development Using Db4oPavel SurninNo ratings yet

- Ket Speaking Sample Part 2Document13 pagesKet Speaking Sample Part 2Miriam MGNo ratings yet

- Relative ClausesDocument9 pagesRelative ClausesErickishi FlowersNo ratings yet

- The Language of The AngelsDocument14 pagesThe Language of The AngelsАлександар ТучевићNo ratings yet

- Full Story HeavenDocument20 pagesFull Story HeavenstumbleuponNo ratings yet

- IndiaDocument153 pagesIndiasayan biswasNo ratings yet

- An Investigation Into Politeness, Small Talk and Gender: Rebecca BaylesDocument8 pagesAn Investigation Into Politeness, Small Talk and Gender: Rebecca BaylesMao MaoNo ratings yet

- Blog 5 by Bridge Troll-D4a80j0Document1,482 pagesBlog 5 by Bridge Troll-D4a80j0Dan Castello BrancoNo ratings yet

- Four Rules of FractionsDocument25 pagesFour Rules of FractionsJosé Antonio Luque LamaNo ratings yet

- Barriers To Communication and Principles For Effective CommunicationDocument12 pagesBarriers To Communication and Principles For Effective Communicationpoojadixit9010No ratings yet

- ENGLISH Pre Board 1 XII Eng - 221226 - 203725Document16 pagesENGLISH Pre Board 1 XII Eng - 221226 - 203725ItsAbhinavNo ratings yet

- Cover and Spine UniKL Thesis FormattingDocument11 pagesCover and Spine UniKL Thesis Formattingonepiece94100% (1)

- LogicalDocument8 pagesLogicalMharlone Chopap-ingNo ratings yet

- Mabasa EpamushaDocument9 pagesMabasa EpamushaNevanji NevanjiNo ratings yet

- Part of SpeechDocument20 pagesPart of SpeechGewie Shane Blanco SumayopNo ratings yet

- Communication: What You Need To KnowDocument23 pagesCommunication: What You Need To KnowHenrique AlmeidaNo ratings yet

- CULTURE AND LITERATURE COMPANION Pre-Intermediate Teacher's BookDocument20 pagesCULTURE AND LITERATURE COMPANION Pre-Intermediate Teacher's BookdelphinuusNo ratings yet

- Related Literature and StudiesDocument5 pagesRelated Literature and StudiesMay Ann Agcang SabelloNo ratings yet

- Most Common Mistakes in IELTS Writing Task 1 & How To Learn From ThemDocument4 pagesMost Common Mistakes in IELTS Writing Task 1 & How To Learn From Themab yaNo ratings yet

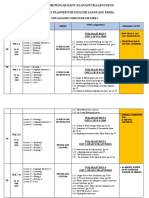

- Sekolah Menengah Dato' Klana Putra Lenggeng 2020 Yearly Planner For English Language PanelDocument11 pagesSekolah Menengah Dato' Klana Putra Lenggeng 2020 Yearly Planner For English Language PanelSabaRajooNo ratings yet

- Alexander, Jeffrey C., and Steven Seidman. Culture and Society: Contemporary Debates. Cambridge University Press, 2000Document6 pagesAlexander, Jeffrey C., and Steven Seidman. Culture and Society: Contemporary Debates. Cambridge University Press, 2000Maria SophiaNo ratings yet

- GOODYEARMusikstädte2012 PDFDocument297 pagesGOODYEARMusikstädte2012 PDFJulián Castro-CifuentesNo ratings yet

- Practice Test 12.76Document4 pagesPractice Test 12.76Thao NguyenNo ratings yet

- Sigil MagicDocument27 pagesSigil Magic꧁?Ꮆเεɠυε’ร Ꮆเ૨l?꧂95% (44)

- Benefits:: Charpak Lab (Previously Charpak Research Internship Program)Document2 pagesBenefits:: Charpak Lab (Previously Charpak Research Internship Program)Manprit SinghNo ratings yet

- OO Concept Chapt3 Part2 (deeperViewOfUML)Document62 pagesOO Concept Chapt3 Part2 (deeperViewOfUML)scodrashNo ratings yet

- Medium/Language - Filipino Pre-Colonial Period: Theme/SubjectsDocument5 pagesMedium/Language - Filipino Pre-Colonial Period: Theme/SubjectsKylya GanddaNo ratings yet