Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Unresolved Struggles Between Project Managers and Functional Managers in Matrix Organizations

Uploaded by

Rolf MedinaOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Unresolved Struggles Between Project Managers and Functional Managers in Matrix Organizations

Uploaded by

Rolf MedinaCopyright:

Available Formats

The unresolved struggles between Project Managers and Functional Managers in Matrix Organizations

Abstract Having personal that works in projects but belongs to a functional organization is the way that many companies organized their labor force today. Previous research shows that this implies management contradictions and ambiguities between functional manager and project manager; there are unresolved struggles between these two roles in terms of power, accountability, authority and legitimacy.

With this paper we aim to analyze those struggles based on previous research and to generate working propositions. We first provide a review of the different matrix organizations focusing on the relation between the functional manager and the project manager. We then review the literature concerning temporary organizations and projects as temporary organizations. We conclude by integrating the findings of these perspectives and by identifying working propositions and areas for further research. Key words: Temporary organization, Matrix organizations, Functional Manager, Project Manager

Introduction

Is a project a part of a companys day-to-day business or an extraordinary task? Is it therefore part of the company being a going concern or is it a standalone building block of the business, which requires dedicated management structures and control mechanisms?

The answers to these questions differ whether seen from the perspective of the functional manager or the project manager, especially in the context of matrix organizations.

These differences in perspective lead to different understandings of objectives and priorities, which can cause struggles between functional and project managers when it comes to assigning resources to projects and resource availability (Engwall 2001, 2003; Turner and Mller, 2003).

According to Forman and Selly (2001), the achievements of the organizations objectives are dependent on the effectiveness of the resource utilizations. This statement makes the above struggles a key concern (source of poor performance) for any organization and raises the following questions: What are the main reasons for the struggles? What are the main factors constituting these struggles? What are the consequences of these struggles?

This paper addresses these questions from a theoretical perspective through a critical review of the literature and suggests a conceptual model that helps to identify the categories of the struggles between project managers and functional managers, and their main characteristics.

On the basis of in-depth investigation of the literature, four main categories of struggles were identified; authority, accountability, legitimacy and power. These four categories of struggles can be defined in different ways and have different strength depending of the theoretical domain that they are applied in. In this paper we use the following definitions which apply to the theoretical domains of organization, management and leadership: 1. Authority is the right to give commands, enforce obedience, take actions or make final decisions (Popper, 1960). 2. Accountability in leadership roles is the acknowledgment and assumption of responsibility for actions, products, decisions, and policies including the administration, governance and implementation within the scope of the role or employment position and encompassing the obligation to report, explain and be answerable for resulting consequences (TutorVista.com, 2010). 3. Legitimacy is a perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper, or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, belief, and definitions (Suchman, 1995). 4. Power is defined as the right or means to command or control others. In organizations there are two major kinds of power: 1. Position power is the power a person derives from a particular office or rank in a formal organizational system. 2. Personal power is the influence capacity a leader derives from being seen by followers as likable and knowledgeable (Northouse, 2009, p7).

The literature on matrix organizations and temporary organizations that we reviewed used these terms without definitions and let the reader make his own interpretations of these terms. Confusions occur when citing definitions, especially between authority and power since the classical definitions of these terms are based on each other (Grimes, 1978). The distinction that we choose to use is based on Grimes (1978) work that states that authority and power are both a type of control and influence. The difference lies on that authority of the role is based on voluntary consensus while the power of the role is base on compliance.

Struggles at work! The above categories of struggles have different manifestations in different matrix organizations. The most often cited evidences of those struggles are those regarding resource allocation to projects and implied priority of projects. Examples include conflicts in which project managers aim to establish changes, which are resisted by functional managers; or conflicts concerning resource utilization when both managers try to optimize their individual objectives at the expense of the other part (Knight, 1976; Mller, 2009; Turner and Mller, 2003; Brown, 2008).

Authority Continuous resource demands by project managers may be perceived by functional managers as a threat to their authority and a loss of accountability (Brown and Botha, 2005). This focus is taken further by Engwall (2001) who emphasizes that functional managers are stuck in between different project managers asking for resources and with no clear authority over those resources. Taking the perspective of the project members we see that their reasons for compliance with functional managers and project managers are different, caused by the perception that project

managers authority is less than the functional managers authorities (Dunne, Stahl and Melhart, 1978).

Accountability Accountability is an issue, for instance, when project managers aim to establish changes, which are resisted by functional managers (Turner 1999; Turner and Mller, 2003; Brown 2008). Dunne, Stahl and Melhart (1978) found empirical evidence that project managers have the responsibility to meet project deliverables, but are not always have the authority to make the required decisions. This creates conflicts.

Legitimacy Another struggle often cited in publications is that of legitimacy. Temporary organizations especially struggle with legitimacy for their management (Martinsuo and Lehtonen, 2007). Engwall (2003, p791) describes the Project Manager as a non-legitimate change agent in a conservative, or sometimes even hostile organizational environment. By broadening this perspective, Lundin and Sderholm (1995) identified legitimacy as a key element in the relation between the temporary organization and its environment, which may cause conflicts between competing teams or organizational structures. Legitimacy of roles might also be affected in matrix organizations by people being more loyal to their functional managers than their project managers since the functional managers conduct their annual appraisal. This decreases the legitimacy of the project manager (Turner 1999).

Power

The fourth struggle that we found is about power. In this paper we refer to Positional power meaning the power that the project manager and the functional manager have from the position their role gives them. Larson and Gobeli (1987) found in their studies evidence of power struggles between project managers and functional managers. The underlying causes for the struggles are competition for the control of the same resources and different personal objectives. Power in leadership and management is based on the classic view of management being planning, organizing, leading, coordinating and controlling (Fayol, 1949). In matrix organizations most of these activities are performed by the project manager, some by the functional manager and others are shared between the two. This creates a power struggle generated by the ambiguity and overlapping of roles. This was treated by Ford and Randolph (1992) in their literature review about integration of matrix and project management. They highlighted conflicts about scheduling, personnel resources, administrative procedures and priorities.

The impact of the control structure Having dual lines of authority and split responsibilities generates ambiguity in many areas such as resources, compensations, loyalty and recognition. This ambiguity generates the struggles (Larson and Gobeli, 1987; Turner, 1999; Ford and Randolph, 1992; Knight, 1976; Engwall, 2001; Pinto and Rouhiainen, 2001). Turner (1999) traces these struggles back to organization structures stating that the struggles are embedded on the structure since matrix structures are combinations of functional hierarchical organization, where the head of a function is responsible for both staff members and deliveries, as well as autonomous project organizations in which the

project manager is responsible for the staff and the deliveries. Taken the organization structure perspective rises the following question: Are there any difference in the way of controlling projects and functional departments?

Ouchi's (1979) work looked at correlation between different organizational structures and the mechanism of control. He identified two major control mechanisms: Output control and Behavior control. Output control is based on controlling the performance and deliveries and is related to organizations, which aim for legitimate objective control and where supervisors cannot supervise their employees directly, for example in functional departments where the resources are assigned to projects. Or project managers in mega projects not having the possibility of supervising the behavior of all the members of the projects. Behavior control on the contrary is based on a holistic approach that focuses on the way that tasks are performed and is only appropriate to the supervisor for a working resource, when the supervisor has a good understanding of the means-end relationship of the behavior. An example of this is a project manager who understands the tasks and the behavior needed to accomplish the task. These differences in control mechanism might affect project managers and functional managers in different ways and contribute to the struggles between the roles.

The above indicates the need for a deeper understanding of the factors and combinations of factors that constitute the struggles between functional manager and project manager. This leads us to address the following research questions:

1. What is the nature and strengths of the factors constituting the struggles between functional managers and project managers in matrix organizations? 2. How do project control mechanisms affect those four categories of struggles? 3. Is there any correlation between the struggles?

Hence, the aim of the present paper is to suggest a framework to identify and assess the nature and strength of factors in matrix organizations that make up the struggles described above. Our unit of analysis is the type of struggles that functional manager and project manager have. The results of this paper will contribute to a better understanding of the nature of these struggles in matrix organizations. It will provide a framework of factors that make up the strength of struggle, and identify further areas for research concerning this subject.

The paper continues with a review of the relevant matrix organization structures. Then it reviews literature of projects as temporary organizations and subsequently outlines the differences between functional organizations and project organizations when it comes to control needs. The paper concludes by integrating the findings of these two perspectives into a framework and defining propositions for further research.

Literature review Matrix organizations

Matrix structure is one of the three classical organizational forms: Functional Organizations, Matrix Organizations and Pure Project Organizations. In functional organizations the staff belongs to a line function and performs all their work within that function, with no or very limited interaction with other functions. The resources are grouped in functional areas such as finance, marketing, design, engineering, production or in skill areas such as chemistry, electronics, aerodynamics etc. The opposite of this organizational type is the Pure Project Organization where all the work is performed in temporary structures or projects that are separate from the parent organization and where the staff does not always belongs to a function. The project manager has full authority over the project and resources. Strengths of this organization type are that project members have one manager and are fully dedicated to the project. In between these two organization types is the Matrix Organization which is a combination of hierarchical structures and lateral communications, work co-operations and authorities. In the matrix functions are the columns and projects are the rows (Turner, 1999; Morgan, 1997).

The main reason for adopting the matrix as an organizational structure is the need for handling high task complexity. The matrix deals with the kinds of communication and decision needs that arise in complex interdisciplinary projects (Knight, 1976). The term matrix organization was coined to capture a visual impression of organizations that systematically attempt to combine the kind of functional or departmental structure of organization found in a bureaucracy with a project team structure (Morgan 1997, p52). Galbraith (1971) and Curran (2002) describe the position of the functions and projects in the matrix. They state that the matrix model creates a horizontal interaction between the vertical functions which connects people across different functions.

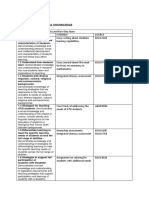

Strengths of the matrix organizations are flexible resource utilization and better focus on tasks. Among weaknesses we find unclear responsibilities and authorities. This implies conflicts and ambiguity for all parties involved; for project managers and functional managers because they share /divide power for project members and stakeholders (Morgan, 1997; Larson and Gobeli, 1987; Andersen, 2000; Galbraith, 1971; Knight, 1976). The pros and cons of matrix organization are presented in Table 1. ----------------------Insert Table 1 here ----------------------Types of matrix organizations The classical categorization of matrix organizations is based on the relation between project and function. There are mainly three different forms: Functional Matrix, Project Matrix and Balanced Matrix, (Larson and Gobeli, 1987; Morgan, 1997).

Functional Matrix Functional Matrix is also called Coordinating Matrix or Functional Project Organization and applies to organizations where the functional manager is responsible for assigning tasks and the project coordinator coordinates tasks between functions. The project in some cases may not have a project manager and the work is performed through the different organizational functions. This type of organization focuses on an optimal use of resources. Common problems are poor quality and poor communication (Turner, 1999; Pinto and Rouhiainen, 2001).

10

Another structure of the functional matrixes is the Lightweight Project Organization, where there is a project manager with an overall responsibility for the project, but with limited power and authority. The functional manager controls the resources and is the one who is in command. In this kind of organizations we find a power conflict between the project manager and the functional manager. The nature of this conflict is based on the roles and the different goals since the project manager is more of a coordinator with no authority to make decisions. The project manager is responsible for the outcome while the functional manager makes the decisions, focuses on an optimal use of resources but not on the outcome (Pinto and Rouhiainen, 2001).

Analyzing the above definitions we see that in the functional matrix the weight is on the functional side and as a consequence the functional manager has higher authority, power and legitimacy than the project manager. The project manager is mostly accountable for the progress of the project and for the deliveries.

Project Matrix On the other extreme we have the Project Matrix, which has its focus and weight on the project dimension. These types of matrix organizations are also called Pure Project Matrix, Secondment Matrix or Autonomous Team Organization. Contrary to the functional matrix, project managers are here the ones making decisions about the realization and decide on the involved staff, while the functional managers are supporting them in the background. This support is mostly performed by providing projects with personnel upon request. The project manager has responsibility for resources, assigns and distributes work, and has the authority, status and responsibility for project success. These organizations focus on problem solving, which (among

11

others) allows for customer-orientation, but they tend to overlook efficiency and costs and may become too expensive. This potentially generates a goal conflict between functional manager and project manager since the functional manager is typically responsible for the efficiency of the organization (and sometimes even for the costs) while the project manager typically concentrates on the deliveries through which he or she might fails take into account the wider organizational picture (Larsson and Gobeli, 1987; Turner, 1999; Pinto and Rouhiainen, 2001).

In the extreme case of project matrix organization, a Full Authority Project Organization, the project manager has full authority and project members are 100 percent allocated to the project. The organization is outside the parent organization and considered a true temporary organization (Andersen, 2000). In their empirical study, Morrison, Brown and Smit (2006) found out that in this type of organizations the projects are large or semi-permanent and this gives the project manager legitimacy in the organization. This legitimacy means that the project managers inputs and requests are being considered and can influence the parent organization and that their role is recognized as a key role. Functional managers on the other side, see their roles limited by little authority and are considered by the organization a supportive role.

An analysis of these definitions shows that in project matrix organizations the weight is on the project side and the project manager has authority, power and legitimacy. On the other hand the functional manager might face struggles in these areas due to the limited involvement and possibilities to decide on the projects. The findings of Larson and Gobelis (1987) study show that the struggles between the roles are differently moderated in this type of matrix organization.

12

Balanced Matrix In a Balanced Matrix the power is divided between the project manager and functional manager. Project managers decide and plan what has to be done and functional managers are responsible for how the work will be done. These organizations are a mix of functional hierarchies and pure project-oriented structures. This positions the balanced matrix organizations in-between the functional matrix and the project matrix. In these organizations the project managers and functional managers share responsibilities, the project manager is responsible for time and cost and functional manager for scope and quality (Larsson and Gobeli, 1987; Turner,1999; Pinto and Rouhiainen, 2001).

Balanced Matrix Organizations are generally implemented in order to share resources between functional work and project work and to create better balance between function and projects. However, this may be difficult because dual authorities result in authority problems between Project Manager and Functional Manager (Morrison, Brown and Smit, 2006; 2008). As a result of unclear authorities, project managers might have less legitimacy and less authority than the functional managers to influence the parent organization. The reason for this phenomenon could be that the project managers tend to be isolated from the traditional function area of expertise. By not being involved they face difficulties in gaining credibility and possibilities to be heard at senior levels in the organization (Ford and Randolph, 1992).

Heavyweight Project Organizations are often organized around products or services which require focus on customer needs and expectations (Pinto and Rouhiainen, 2001). In this type of organizations the project managers share responsibilities and authorities with the functional

13

manager, the areas of accountability are specific for each of the roles but sometimes overlap each other, thus generating power conflicts.

Andersen (2000) called this type of organization Split Authority Project Organization. His emphasis is on the splitting of authority and work, since project members are recruited from different functions and they need to perform both project work and functional work. Project managers share authority with functional managers.

Research has shown that power struggles occur especially in the Balanced Matrix Organization because its nature does not clearly define power and authority by role (Larson and Gobeli, 1987). Project managers are considered responsible for deliveries but do not have the authority to acquire resources (Brown, 2008).

Accountability issues may arise as well in balanced matrix organizations through the ambiguity of situations in which the functional managers have the responsibility for assigning personnel to a project and are responsible for the result of their functional area, while project managers set the schedule and manage the project (Larsson and Gobeli, 1987). According to the conceptual study of Goold and Campbell (2002), matrix organizations might collapse because of this lack of clarity about responsibilities and accountabilities between the project managers and the functional managers.

Summary of Matrix organizations review

14

The literature review showed a lack of common definitions and classifications of matrix and project organizations. The differences are not only the names but also the definitions and responsibilities of the project manager and functional manager. For example, for Larson and Gobeli (1987) the project manager in a balanced matrix is responsible for the scope, while for Turner (1999) the scope in a balanced matrix is the responsibility of the functional manager. This example illustrates the need for harmonization, unification, or at least a context dependency of definitions. It also shows that the term balanced matrix cannot be used without further definition, because it has different meaning for different writers. This paper adopts the definition of Knight (1976), where a Balanced Matrix Organization is seen as an organization with a vertical functional structure and a horizontal project structure. In this organization the functional managers are responsible for the line organization; they have responsibility for resources, competence development, promotion, employee evaluation, and recruiting new staff. They are also responsible for providing projects with staff when requested and balancing these requests with available resources. When a project is finalized the functional manager is responsible for transferring the knowledge that has been acquired by the project members to the line organization (Turner, 1999). The functional manager could do the first preliminary definition of the scope and the goal of the project. The identification of the scope is based on the strategy, aligning the function with the strategy is one of the main responsibilities of the functional manager (Larsson and Gobeli, 1987). The definition of the scope and the project goal could also come from other stakeholders. In this case the functional manager is not the initiator of the project but is still the owner of the project initiation in relation to the project manager. The final scope and goals need to be handled and stated by the project manager.

15

Meaning that the project manager needs to do an analysis of the requested outcome and an adjustment of the initial goals and requested deliveries.

Among the above descriptions, seems to be a consensus that a balanced matrix distributes power, authority and responsibility in a shared manner or allows for an overlap between the project manager and functional manager authorities. It is in this type of organization where we find most struggles.

Table 2 summarizes the above review of matrix typologies and its classifications, focusing on the project manager and functional manager. It also shows that the role of the project manager and functional manager differs depending on the type of matrix organization. Power, responsibilities and accountabilities of these two roles are thus dependent on the organizational structure. ----------------------Insert Table 2 here ----------------------Having reviewed the different types of matrix organizations we have seen that there are differences in the categories of struggles between project managers and functional manager in each one of these organization types. We were unable to find theoretical evidence for legitimacy struggles being present in functional matrix and in balanced matrix structures. Table 3 maps some of the factors that constitute the category of struggles for each type of matrix organization. -----------------------Insert Table 3 here

16

----------------------The critical literature review indicates: If the functional manager has stronger power and authority his/her role may have stronger legitimacy in the organization. On the contrary, if the project manager has more power and authority over the resources, the plans and the outcomes, his/her role may have the stronger legitimacy. Different degrees of responsibility sharing will also influence the legitimacy of the roles, i.e. if the project manager is responsible for the outcome but cannot influence the selection of resources or the end date of the project. Especially when this is the responsibility of the functional manager it may lead to equal levels of legitimacy, but it can also minimize the legitimacy of the project manager.

This leads to the first two propositions: Proposition 1a: The legitimacy struggles in matrix organizations depend on the distribution of power, authority and accountability between the project manager and the functional manager. Proposition 1b: Legitimacy struggles are dependent on the type of matrix structure.

Projects as Temporary Organizations In this section we will review projects as temporary organizations, in order to provide a broader spectrum of project organizations. Looking at projects as temporary organizations we can classify them in two types. In the first type people in the organization alternate between different projects and do not have a manager outside these projects. This is typical for movie and theatre productions. These organizations focus on the skills of the team members; they are expected to

17

perform complex tasks with little coordination (Goodman and Goodman, 1976; Bechky, 2006). The second type of projects as temporary organization comes from the matrix organizational form, where project members belong to functional departments in form of resource pools, from where they are lend out to the different projects.

We are going to review both types of temporary organizations, but prioritize the second type because the purpose of the present study is to focus on the struggles between project manager and functional manager and these are more often associated with the second type of temporary organizations.

A large amount of existing literature is based on standards such as The Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK) from the Project Management Institute (PMI) 1 and has a tendency to focus on the project itself. It pays little attention to the organization and environment that surrounds the project. Engwall (2003) introduced a contingency-based ontology by looking at the surroundings and proposing a conceptualization of projects as contextually embedded open systems; open in both time and space. He stated the importance of seeing temporary organizations as parts of the whole organization and not as isolated entities. This perspective identifies projects as being context dependent on, for example, the surrounding organization, previous projects, other ongoing projects and future projects. It shows the importance of analyzing the struggles between the roles by taking these perspectives into consideration.

PMI is a registered trademark and service mark of the Project Management Institute, Inc

18

Table 4 shows a comparison of the different factors that characterize permanent organizations and temporary organizations. The differences in the factors that characterize temporary organizations and permanent organization may be the underlying the reasons for the struggles between the roles (Lundin and Sderholm, 1995). Project managers of temporary organizations and functional managers of permanent organizations may have different foci, different control mechanism, different relational patterns and work in different organizational structures. The strength of the struggles could vary depending on the dominance of these factors. ----------------------Insert Table 4 here ----------------------Aspects of projects as temporary organizations Several aspects that need to be taken into account when looking at projects as temporary organizations. These are temporariness, context and control mechanisms (Lundin and Sderholm, 1995; Engwall, 2003; Packendorff, 2003). In this section we will review those aspects and see whether they have an impact on the category of the struggles between project managers and functional managers.

Temporariness According to Lundin and Sderholm (1995), temporariness is the primary element to be considered because it represents the main difference between functional and temporary organizations. Time is fundamental to understanding temporary organizations, since they are limited by time. In permanent organizations time is seen as eternal, in temporary organizations

19

time is seen as something that comes to an end. The view of projects as temporary organization which coexists within permanent organizations has an impact on both organizations.

Considering temporariness as a crucial aspect there are differences on its impact on projects depending on their categorization. Janowicz, Bakker and Kenis (2009) categorized temporariness in: 1. Temporariness as Short Duration 2. Temporariness as Limited Duration 3. Temporariness as Awareness of Impeding Termination. Defining Temporariness as Short Duration focuses on the limitation of the time available to conduct tasks as well as the time group members are part of the organization. Temporariness as Limited Duration refers to the duration of the temporary organization based on a specific predetermined date, or events or conditions that need to be completed. Temporariness as Awareness of Impeding Termination is a subcategory of the limited duration approach that adds members awareness of limited duration and their behavior in order to cope with this fact (Janowicz, Bakker and Kenis, 2009).

Even though these theories argue that time is the key element of the temporary organization there are different perspectives and implications depending on the different approaches. It implies that time is not only the start and end point of temporary organizations, meaning that when discussing time and its effect on temporary organizations, it is not only the awareness about insufficient time and deadlines what we need to take into consideration.

20

Looking further we see also that time affects the goals of project managers and functional managers. Project managers have a shorter time perspective because of the temporary nature of the project, while functional managers have a longer term overall business perspective, which is based on business result and continuity instead of time (Jugdev and Mller, 2005). This contradiction in the perspective of goals, which is based on time aspects, could generate conflicts between project managers and functional managers. Examples of this conflict are mentioned by Pinto and Slevin (1987) as a result of their empirical research having project managers who are focused on client acceptance and expectation while the functional manager focused on strategic time aspects. In addition to this project managers deal with possible risks stemming from the project members awareness of the temporariness of the project. This may lead them to focus on finding the next assignment, which may impact the effectiveness of the current project and thus the project managers authority (Gadis, 1959). The latter is in contradiction to the findings by Bakker and Janowicz (2009), that the members of a temporary organization focus more on the present than on the past and future. They argued that the members of a temporary organization have a strong present orientation and that this has a positive influence on performance. At the same time team members are mentally decoupled from the rest of the organization. This implies that the functional manager has limited authority and possibilities to influence the project members. The above indicates that depending on the two above approaches, the authority of the project manager and the functional manager may differ. If the project members focus on the present the project manager may have higher authority, if the project members focus on the future and the next assignment the functional manager may have more authority.

21

How does temporariness affect legitimacy? The findings of Janowics, Kenis and Vermeulen (2009) showed that external legitimacy, meaning the legitimacy of the project outside the project organization, is affected negatively by temporariness. This is generated by the fact that temporary organizations function in isolation from the structures of their context. As a consequence of this temporary isolation temporary organizations tend to create their own norms that diverge from those of the permanent parent organization. This may affect the external legitimacy; affect the capacity of receiving support and the project manager possibilities of being heard within the organization. This leads to a weakness in the ability to perform the tasks. Especially if newly developed norms in a project challenge the established norms of the parent organization (Engwall, 2003; Lundin and Sderholm, 1995).

Is there a relation between temporariness and the distribution of power between project managers and functional managers? The answer to this question may depend on the definition of temporariness. In short duration temporariness power should benefit the functional managers since they have the long term perspective in their roles, meaning that the project members will be more loyal to their long term manager or supervisor (Turner, 1999).

Temporariness as limited time may be favorable for the project manager since there is a specific event or date that marks the end of the organization. Focusing on the event could give the power of leading and using the event as a power mechanism (Lundin and Sderholm, 1995; Bechky, 2006).

22

Having the perspective of temporariness as impeding termination could give more power to one of the roles depending on the situation and the mechanism that the team members use to cope with the fact that the project is only temporary. If the project members strategy to cope with the insecurity that the temporariness causes led them to situations of isolation from the line organization, then the likelihood of power reduction on the side of the functional manager is reduced. Similarly, if the project members do not strive to move towards termination of the project, the power of the project manager in his or her role to lead the project towards its goals may be reduced.

Temporariness in general could also lead to a power balance between project managers and functional managers since, according the findings of Bakker and Janowicz (2009), the members awareness about the unexciting or low probability of future collaboration make them concentrate on the present with little or no focus on the future. Thus leading to higher creativity and innovation. The reason for this phenomenon is that the members are acting in a protective bubble, guarded from the shadow of the future and the burden of the past (Bakker and Janowicz, 2009 p128). This underlying factor could give project managers a committed and motivated team and could give the functional manager fast paced zone which works in a short time towards the long time goals.

The above review shows that temporariness has potentially an impact on the struggles in authority, legitimacy and power between project managers and functional managers. Thus having an impact on the temporary organization. It also shows that the time impact could have both positive and negative consequences for both project and the functional organization.

23

Context As mentioned in the previous section; Engwall (2003) addresses the Context aspect of a project, stating that it is highly dependent on the surrounding organization, on previous projects, other ongoing projects and future projects. In his research he found that the degree to which project management approaches challenge norms and structures of the parent organization affect the results of the projects. The more project management challenges established structures and norms of the organization, the smaller the chance to succeed.

Does context affect the four categories of struggles? Before answering this question, it is necessary to clarify that there are different contexts perspectives: Considering the context of projects requires to look at organizational aspects and perceive the parent and temporary organization as distinct entities. This perspective allows to look at the relationship between the two organizations from an Principal Agent Theory perspective. Jenssen and Meckling (1976), describe Principal Agent Theory as a relationship between two institutions (people or organizations) where one institution, which is called the principal, delegates works to another institution, which is called the agent. Their relationship is subject to two agency problems, which occur when both try to maximize their own utility in their relationship. These are goal conflict and the difficulty and cost that the principal faces in order to control the agent. This conflict of interest has it nature in the differences of goals. The principal may wish that the agent run the organization (e.g. a project) in a way that increases the value for the principal. On the other hand, the agent may wish to manage the organization (e.g.

24

the project) in ways that maximize the agents personal goals, which may not be in the best interests of the principal (Jensen and Meckling, 1976; Eisenhardt, 1989).

Agency problems in relation to project management were, among others, discussed by Mller (2009), Andersen (2009), Eisenhardt (1989), Turner and Mller (2003). These authors considered the parent organization as the principal and the project organization as the agent, or assumed that the sponsor or project owner is the principal and the project manager is the agent. There is a risk for conflict of interest if these two are not completely aligned in their goals, information and directions. Elimination of this risk will rarely be possible because the project manager as the agent focuses on project performance and the project owner as the principal focuses on the parent organization with a broader set of objectives. The agency problem stems from the separation of ownership and management. The project manager as an agent manages the project, but the project is owned by the principal If the principal is the functional manager we might find power struggles between the project manager and the functional manager.

The underlying assumptions of Principal Agent Theory are challenged by Stewardship Theory, which questions the assumption that a principal agent relationship will always be characterized by a conflict. This theory states that, on the contrary to the agency assumption, the agent will act in the interest of the principal and focus on generating benefit for the principal and not for his/her own interest (Davis, Schoorman and Donaldson, 1997; Donaldson and Davis, 1991; Lee and ONeill, 2003).

25

Mller (2010) relates the two theories to the type of industries, where agency theory is applied in for-profit organizations but might not be appropriate for non-profit sectors. In non-profit sectors Stewardship theory is applied, due to collaborative approaches between the principal and the steward. Stewardship Theory assumes a different relationship between project managers and their context and thus a different relationship towards the functional mangers, because of synchronization of objectives and a mutually supportive relationship.

Considering the functional lines of the organization as context, Brown (2008) found empirical evidence of the lack of legitimacy of project managers as a consequence of the challenging changes that projects generate on the functional lines. Furthermore she found that there was a correlation in this area that depended on the extent in which the project was challenging the permanent organization. This is also supported by Engwall (2001) and his empirical study of two projects that were among the biggest capital investment projects carried out in Scandinavia during the late 1980s. His finding does not only support the legitimacy disadvantage of the project manager in relation to the functional manager, he also relates authority and accountability struggles to it.

Summarizing the above in relation to projects as temporary organizations and their context, principal agent theory is based on the assumption that there is a conflict of interests and therefore a need for control. This might affect the authority of project managers because they are controlled by functional managers. While stewardship theory is based on a harmonization of interests between the project and it context and therefore collaboration and trust are developed.

26

Furthermore, prior research indicates that that the contexts of projects impact on the four categories of struggles.

Control Mechanism Control Mechanism in temporary organizations differs from those of permanent organizations in a way that the focus is on relations instead of controlling by lines of authority (Bechky, 2006). Temporary organizations tend to develop their own mechanisms of control, which are based on interpersonal processes (Packendorff, 2003). This can be observed not only in firms, but also in theater groups and film teams. Temporary organizations need to deal with tasks and environmental uncertainty; this is managed by interpersonal processes instead of formal structures. These interpersonal processes are the base of the control mechanisms, indicating behavior control as stated by Ouchi (1979). A temporary organization does not necessarily become an unstructured work organization. On the contrary it tends to develop alternative and normative rules (Bechky, 2006).

Control mechanisms can be based on project performance, project deliverables and project behavior, or through controlling the gap between project preferences and parent organization. The last mentioned control mechanism is a holistic approach which is based on achieving common values and beliefs within the parent organization and project organization (Andersen, 2009).

The above addresses differences in the way of controlling projects and the way of controlling permanent organizations. These differences might affect project managers and functional

27

managers in different ways and contribute to the struggles between their roles. Controlling a project in the same way as controlling a plan affects the autonomy of the project and this lead to an authority disadvantage for the project manager (Packendorff, 2003). On the other hand if the parent organization does not have any other way of influencing and or participating in the work of the temporary organization than controlling the performance or the deliveries, the functional manager authority might be weaker or even imbalanced in relation to the project manager (Turner and Mller, 2003; Mller and Turner, 2005). This may also have an impact on legitimacy, because if the project is not accepted as organization, the project managers legitimacy will be lower than that of the functional manager (Brown, 2008). As a consequence, this could also influence team commitment and loyalty (Turner, 1999).

Does the control mechanism affect the power struggles between project managers and functional managers? Based on the above we argue that control mechanisms for the project also influence the power struggle and distribution of power between the managers roles. By creating alternative norms and rules and by the projects isolation the project manager might have a strong power within the project. Then the functional manager may be limited to controlling the outcome with no possibility to influence the performance of the work. Contrarily the functional manager could control the outcome of the project and also controls the project manager itself and has the majority of the power.

Applying the holistic control mechanism mentioned by Andersen (2000), meaning controlling what the project manager is doing and not only that he/she is delivering could lead to a different scenario. The risk for conflict is minimized by taking actions that minimize the divergence of

28

goals between project managers and functional managers. Thus a holistic control mechanism may contribute to a better balance minimizing the power struggle.

The above review shows that control mechanisms of projects as temporary organizations impact on the four categories of struggles. Prior research found evidence of both advantages and disadvantage for the project manager and the functional manager.

Summarizing the review on projects as temporary organizations The review of literature on projects as temporary organizations indicates that the four categories of struggles are affected by temporariness, project context and project control mechanisms (see Table 5).

Furthermore, a gap in previous research was identified in terms of the impact that the combination of temporariness, context and control mechanisms has on the four categories of struggles. Further research in this area is suggested.

Huemann (2010), Turner, Keegan and Huemann (2008), Sderlund and Bredin (2005), stated that HRM practices related to project as temporary organizations is an unexplored area. There is also a need for clarification of the project managers responsibility in HRM practices and of moving some HR responsibilities to the project manager. This is needed because the project manager is affected by HR decisions but is not participating in them. The functional manager, on the other hand, is having problems in following the competence development of his/her personal while they are allocated to the projects (Sderlund & Bredin, 2005). HRM practices are a

29

challenge in temporary organizations because they require a new way of managing and a role demand that differs from the role in traditional organization structures (Turner et al., 2008). Looking at companies that perform most of their activities in projects we see that Project managers carry out HRM tasks for project team members, even if he or she has no personnel authority (Huemann 2010,p 367). These facts might contribute to the tension between the two roles but further research is needed to determinate if the distribution of HRM practices between the Project Manager and the Functional Manager has an impact on the four struggles that we are studying.

Table 5 presents a selection of the previous research on the aspects of temporary organizations and the different categories of struggles. ----------------------Insert Table 5 here ----------------------Analyzing the table allows us to purpose the following propositions: Proposition 2a: The legitimacy of the project manager is affected negatively by temporariness, project context and project control mechanisms. Proposition 2b: Mutually supportive relations between project managers and functional managers lead to reduction of authority, power and accountability struggles Proposition 3c: The unclear distribution of HRM responsibilities is a source of tension between project managers and functional managers. Conclusions and areas for further research

30

Having reviewed the literature on matrix and temporary organizations, combining these two domains of studies and focusing on Project Manager and Functional Manager, we have found that struggles about Power, Authority, Accountability and Legitimacy are mentioned. These struggles have been discussed from the early literature on matrix organizations until the latest contributions. There seems to be consensus that these are frequently present in matrix settings. This does not mean that these are the only struggles that need to be considered. Further research is needed in order to determine if they are important struggles and to decide how to measure them.

Our conclusion is that the nature and factors that underlie the struggles between project managers and functional manager are grounded in the organizational structures and control structures. The different matrix organizations distribute power, authority, accountability and legitimacy between project managers and functional managers in different ways. The strength of the struggles may vary with the organizational structure and control structure. Applying agency theory and seeing projects as agencies, lead us to the conclusion that the nature of the struggles lies in the roles where the project manager (the agent) knows more about project issues, content and projects members than the functional manager (the principal). The principal may not understand why the agents makes the choices they do. Both the agent and principal may try to maximize their own utility and in situations where the objectives are not aligned struggles will arise (Turner and Mller, 2003; Mller and Turner, 2005; Jensen and Meckling, 1976). We also see indications of relationships between the parameters that define temporary organizations (i.e. temporariness, control mechanisms and context), and the four struggles (i.e.

31

accountably, authority, power and legitimacy). This paper has identified the need for more empirical research in this area.

32

References Andersen, E. (2009) Two perspectives of project management, EURAM. 2009. 9 th. 11th 14th May, Liverpool. Andersen, E. (2000). Managing organization-structure and responsibilities, in Turner, J. R., & Simister, S. J. (eds.) Gower Handbook of Project Management (Vol. 3rd, pp. 277-292). Hampshire, UK: Gower Publishing Ltd. Bakker, R.M., & Janowicz,M. (2009). Time Matters: the impact of temporariness on the functioning and performance of organizations in Temporary Organizations Prevalence, Logic and Effectiveness Kenis,P. ,Janowicz,M.and Cambre, B. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited. Bechky, B. A. (2006). Gaffers, Gofers, and Grips, Role-Based Coordination in Temporary Organizations. Organization Science, 17(1), 3-21. Brown, C. J. (2008). A comprehensive organisational model for the effective management of project management. South African Journal of Business Management, 39(3), 1-10. Brown, C. J., & Botha, M. C. (2005). Lessons learnt on implementing project management in a functionally-only structured South African municipality. South African Journal of Business Management, 36(4), 1-7. Curran, C. J. (2002). The Myth of Equality in Flatline Organizations. OD Practitioner, 34(4), 40-46. Davis, J. H., F Schoorman. D. & Donaldson L (1997). Toward a stewardship theory of management. Academy of Management Review 22(1): 20-47. Donaldson, L., & J. H. Davis (1991). Stewardship Theory or Agency Theory: CEO Governance and Shareholder Returns. Australian Journal of Management 16(1): 49. Dunne Jr, E. J., Stahl, M. J., & Melhart Jr, L. J. (1978). Influence source of project and functional managers in matrix organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 21(1), 135-140. Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Agency theory: An assessment and review. Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 57-74. Engwall, M. (2001). Moving Out of Plato's Cave: Toward a Multi-Project Perspective on Project Organizing. Fenix WP 2001:8. Engwall, M. (2003). No project is an island: linking projects to history and context. Research Policy, 32(5), 789-808. Fayol, H. (1949). General and Industrial Management. London: Pitman. (Translated by C. Storra from the original Administration Industrielle et Gnrale 1916) Ford, R. C., & Randolph, W. A. (1992). Cross-Functional Structures: A Review and Integration of Matrix Organization and Project Management. Journal of Management, 18(2), 267. Forman, E., & Selly M A. 2001. Decision by Objectives: How to Convince Others That You Are Right. World Scientific Publishing, River Edge, NJ, 402. Gaddis, P. O. (1959). The project manager. Harvard Business Review, 37(3), 89-97. 33

Galbraith, J. R. (1971). Matrix organization designs. Business Horizons, 14(1), 29. Galbraith, J. R., & R. K. Kazanjian (1986). Organizing to implement strategies of diversity and globalization: The role of matrix designs. Human Resource Management 25(1), 37-54. Goodman, R. A. (1971). Organization and the effective use of human resources. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 9(1), 55-68. Goodman, R. A., & Goodman, L. P. (1976). Some Management Issues in Temporary Systems: A Study of Professional Development and Manpower--The Theater Case. Administrative Science Quarterly, 21(3), 494-501. Goold, M., & Campbell, A. (2002). Do You Have a Well-Designed Organization?, Harvard Business Review, 80(3), 117-124. Grimes, A.J. (1978) Authority, Power, Influence and Social Control: A Theoretical Synthesis, Academy of Management 3(4), 724-735. Huemann, M. (2010) Considering Human Resource Management when developing a projectoriented company: Case study of a telecommunication company, International Journal of Project Management, 28(4) 361-369. Janowicz,M., Bakker, R.M., & Kenis,P. (2009) Research on temporary organizations: the state of the art and distinct approaches toward Temporariness in Temporary Organizations Prevalence, Logic and Effectiveness, Kenis,P.,Janowicz,M.,Cambre,B. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited. Janowicz, M., Kenis, P., ,R,M., & Vermeulen,P.(2009). The atemporality of temporary organizations: implications for goal attainment and legitimacy in Temporary Organizations Prevalence, Logic and Effectiveness, Kenis,P.,Janowicz,M.,Cambre,B. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited. Jensen, M. C., & W. H. Meckling (1976). Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3, 305-360. Jugdev, K., & Mller R. (2005). A retrospective look at our evolving understanding of project success. Project Management Journal 36(4), 19-31. Katz, R. (1982). The effects of group longevity on project communication and performance, Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 27, No. 1, 81-104. Katz, R., & Allen, T.J. (1985). Project performance and the locus of influence in the R & D matrix. Academy of Management Journal, 28(1), 67-87. Knight, K. (1976). Matrix organization: a review. Journal of Management Studies, 13(2), 111130. Larson, E. W., & Gobeli, D. H. (1987). Matrix Management: Contradictions and Insights. California Management Review, 29(4), 126-138. Lee, P. M., & ONeill, H. M. (2003) Ownership structures and R&D investments of U.S. and Japanese firms: agency and stewardship perspectives., Academy of Management Journal, 46, 212-225. Lundin, R. A., & A. Sderholm (1995). A Theory of the Temporary Organization., Scandinavian Journal of Management, 11(4), 437-455. 34

Martinsuo, M., & Lehtonen, P. (2007). Institutional Transformation through Temporary Organizing. Comparison of two Approaches., 23rd EGOS European Group for Organization Studies Colloquium, 5-7 July 2007, Vienna, Austria. Morgan, G. (1997). Images of Organization. London: SAGE Publications. Morrison, J. M., Brown, C. J., & Smit, E. V. D. M. (2006). A supportive organisational culture for project management in matrix organisations: A theoretical perspective. South African Journal of Business Management, 37(4), 39-54. Morrison, J. M., C. J. Brown, et al. (2008). "The impact of organizational culture on project management in matrix organizations". South African Journal of Business Management 39 (4), 27-36. Mller, R. (2009). Project Governance, Farnharn: Gower Publishing Limited. Mller, R. (forthcoming). Project Governance, in Morris, P., Pinto, J. & Sderlund, J. (eds.), Oxford Handbook of Project Management, Oxford University Press, UK. Mller, R., & J. R. Turner (2005). The impact of principal, agent relationship and contract type on communication between project owner and manager. International Journal of Project Management 23(5), 398-403. Northouse, P.G., (2009). Leadership Theory and Practice (fifth edition). Sage Publications Inc., California USA. Ouchi, W. G. (1979). A Conceptual Framework for the Design of Organizational Control Mechanisms. Management Science 25(9), 833-848. Packendorff, J. (2003). Projektorganisation och Projektorganisering: Projekt som plan och temporr organisation. 2:a upplagan. Ume: Handelshgskolan i Ume, Inst fr Fretagsekonomi. Pinto, J. K., & Rouhiainen, P. (2001). Buildning Customer-Based Project Organizations. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Pinto, J.K., & Slevin, D.P. (1987), Critical factors in successful project implementation, IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, Vol. 34 No. 1, 22-8. Popper K. (1960) On the Sources of Knowledge and Ignorance in Popper selections, D Miller (Ed) Princeton University Press 1985. Project Management Institute (PMI). (2004), A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOKR Guide), 3rd ed., Newton Square, PA: Project Management Institute. Sderlund, J., & Bredin, K. (2005), Perspektiv p HRM., Malm: Liber Ekonomi. Suchman, M. C. (1995). Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches, Academy of management review 20(3), 571-610. Turner, J. R. (1999). The handbook of Project-based Management: Improving the Process for Achieving Strategic Objectives, 2nd ed., London: McGraw Hill. Turner, J.R., Huemann, M., Keegan, A.E., 2008, Human Resource Management in the Projectoriented Organization, Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute.

35

Turner, R., & Mller R. (2007). Choosing Appropriate Project Managers: Matching Their Leadership Style to the Type of Project. PM Network 21(3), 83-83. Turner, J. R., & Mller, R. (2003). On the nature of the project as a temporary organization. International Journal of Project Management, 21(1), 1. TutorVista.com 2010, http://www.tutorvista.com/ 2010/10/8.

36

Table 1. Matrix organizations pros and cons

Matrix organization Efficient use of resources Citation Goodman 1971 Galbraith 1971 Knight 1976 Larson and Gobeli 1987 Ford and Randolph 1992 Turner 1999 Andersen 2000 Morrison, Brown and Smit 2006 Galbraith 1971 Knight 1976 Larson and Gobeli 1987 Knight 1976 Larson and Gobeli 1987 Ford and Randolph 1992 Knight 1976 Larson and Gobeli 1987 Ford and Randolph 1992 Knight 1976 Larson and Gobeli 1987 Ford and Randolph 1992 Engwall 2001 Brown and Botha 2005 Morrison, Brown and Smit 2006;2008 Brown 2008 Knight 1976 Galbraith and Kazanjian 1986 Larson and Gobeli 1987 Engwall 2001 Brown and Botha 2005 Morrison, Brown and Smit 2006 Brown 2008 Knight 1976 Galbraith and Kazanjian 1986 Larson and Gobeli 1987 Ford and Randolf 1992 Andersen 2000 Engwall 2001 Morrison, Brown and Smit 2006;2008 Brown 2008 Knight 1976 Larson and Gobeli 1987 Knight 1976 Galbraith and Kazanjian 1986 Ford and Randolph 1992 Turner and Mller 2007

Pros

Flexibility

Improved motivation and commitment

Improved communication lateral and vertical Cons Power struggles between the project manager and functional manager

Competition concerning resources

Ambiguity and role conflict due to duality

Monitoring and control Higher administrative cost

37

Table 2. Summary of matrix organization typologies, PM and FM perspective

Matrix organizations typologies: a selection (Functional Manager (FM), Project Manager (PM)) Functional Project Matrix Balanced Matrix Matrix PM: Responsible Shared responsibilities PM: Coordinator for staff and PM: Design and plan FM: Responsible realization Responsible for the for staff and FM: Supporting What deliveries FM: Responsible for the work, for the How Coordinating Secondment Balanced Matrix Matrix Matrix Share responsibilities PM: Coordinator PM: Responsible PM: Responsible for FM: Responsible for staff and for time and cost for staff and assigning work FM: Responsible for assigning work FM: Providing scope and quality personnel Split Authority Project Organization Shared authority between PM and FM Lightweight Project Organization PM: Coordinator FM: Responsible for the staff and assigning work.

Larsson and Gobeli 1987

Turner 1999

Andersen 2000 Pinto and Rouhiainen 2001

Heavyweight Project Organization Shared Responsibilities between PM and FM

38

Table 3 Category of struggles and type of matrix organization

Functional Matrix Authority PM faces struggles in this area (Pinto and Rouhiainen, 2001). The FM retain the ultimate decision making authority (Ford and Randolf, 1992). Project Matrix FM faces struggles due to the fact that the PM has the authority to control both resources and project direction (Ford and Randolf, 1992). In general un-clarity about authority is largely absent (Morrison, Brown and Smit, 2006). FM faces struggles in this area because the cost and long term accountability that is part of the role are threatened by a problem solving and customer focus applied by PM who have more authority (Morrison, Brown and Smit, 2006). There are struggles in this area there are generated by shared or split accountability regarding resources, technical issues, salaries and personnel management (Kats and Allen, 1985). Balance Matrix Both PM and FM faces authority struggles due the split boundary of authority (Larsson and Gobeli, 1987; Brown 2008).

Accountability

PM is accountable for the result but faces accountability struggles due to ambiguity and lack of authority (Turner, 1999).

Power

PM and FM faces conflict dues to ambiguity of goals (Pinto and Rouhiainen, 2001).

Both PM and FM faces Power struggles moderate power struggles between PM and FM as (Larson and Gobeli,1987). a result of the ambiguity regarding accountabilities and responsibilities (Ford and Randolf, 1992). FM faces struggles in this area due to limited authority (Morrison, Brown and Smit, 2006). To date no theoretical evidence.

Legitimacy

To date no theoretical evidence.

39

Table 4. Comparison between permanent and temporary organizations Factors Focus on Relation to Controlled by Permanent Organization Long-term Survival Turner (1999) Organizational hierarchy Engwall (2003) Formal Structures Bechky (2006) Temporary Organization Time Lundin and Sderholm (1995) Context Engwall (2003) Interpersonal Processes and alternative Control Mechanisms. Pakendorff (2003)

40

Table 5. Selection of temporary organizations and struggles Temporariness Authority Benefit the authority of PM if the project members focus on the present and benefit the FM if the focus is on the future (Bakker and Janowicz, 2009). Context Applying he stewards theorys approach gives mutually supportive relation between PM and FM and thus a reduction of the authority struggle (Mller 2010). Applying the Agency theory is a disadvantage for the PM (Mller, 2009; Andersen, 2009; Eisenhardt, 1989; Turner and Mller, 2003). Applying the Agency theory gives disadvantage for the PM or FM depending on the context (Mller, 2009; Andersen, 2009; Eisenhardt, 1989; Turner and Mller, 2003). Project control Mechanisms Create disadvantage for the PM (Packendorff, 2003).

Accountability and Power

Legitimacy

Benefit the FM (Turner 1999), Balanced between PM and FM (Bakker and Janowicz, 2009) Benefit the PM (Lundin and Sderholm, 1995; Bechky, 2006). Affects the legitimacy of the PM negatively (Janowics, Kenis and Vermeulen, 2009; Lundin and Sderholm, 1995; Katz, 1982).

A holistic approach will balance the power between the roles (Andersen, 2009).

Affects the legitimacy of the PM negatively specially if the project challenges the permanent organization (Brown, 2008; Engwall, 2001).

Lower for the PM (Turner, 1999).

41

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Developmental Research For Information and TechnologyDocument21 pagesDevelopmental Research For Information and TechnologyZelop Drew100% (2)

- WIREs Climate Change - 2021 - Moore - Transformations For Climate Change Mitigation A Systematic Review of TerminologyDocument25 pagesWIREs Climate Change - 2021 - Moore - Transformations For Climate Change Mitigation A Systematic Review of TerminologyPasajera En TranceNo ratings yet

- EDUC4185 Assignment 2Document9 pagesEDUC4185 Assignment 2DavidNo ratings yet

- A Methodology For Evaluating Transit Service Quality Based On Subjective and Objective Measures2011Document10 pagesA Methodology For Evaluating Transit Service Quality Based On Subjective and Objective Measures2011dewarucciNo ratings yet

- Full Download Sociology in Modules 3rd Edition Schaefer Test BankDocument35 pagesFull Download Sociology in Modules 3rd Edition Schaefer Test Bankgaylekourtneyus100% (38)

- Social Ewom: Does It Affect The Brand Personaility and Purchase Intention of Air Conditioner BrandsDocument43 pagesSocial Ewom: Does It Affect The Brand Personaility and Purchase Intention of Air Conditioner BrandsShahroz AsifNo ratings yet

- 3 Effects of Lowest Bidding PDFDocument15 pages3 Effects of Lowest Bidding PDFMuhammad IqbalNo ratings yet

- Thesis On Alternative Learning SystemDocument6 pagesThesis On Alternative Learning Systemlesliedanielstallahassee100% (2)

- Research Proposal - Marvingrace M.Document16 pagesResearch Proposal - Marvingrace M.tyrion mesandeiNo ratings yet

- Human Nature Thesis StatementDocument8 pagesHuman Nature Thesis Statementamymoorecincinnati100% (2)

- Language and DiplomacyDocument182 pagesLanguage and Diplomacyasdf142534asd75% (4)

- JND & KND Analysis of Inter & IntraDocument9 pagesJND & KND Analysis of Inter & Intravirus_xxxNo ratings yet

- Content & Writing of Chapter 2Document21 pagesContent & Writing of Chapter 2Renz Patrick M. SantosNo ratings yet

- Interpretation and Report WritingDocument13 pagesInterpretation and Report Writingpopat vishalNo ratings yet

- Australia Award ScholarshipsDocument11 pagesAustralia Award Scholarshipskashi aliNo ratings yet

- Writing Essays On EducationDocument1 pageWriting Essays On EducationAnjaliBanshiwalNo ratings yet

- Creative CommunitiesDocument182 pagesCreative CommunitiesDavid PuentesNo ratings yet

- Anglia Ruskin Dissertation GuidelinesDocument8 pagesAnglia Ruskin Dissertation GuidelinesPaperWriterServiceMinneapolis100% (1)

- Research in Marketing Ethics: Continuing and Emerging ThemesDocument6 pagesResearch in Marketing Ethics: Continuing and Emerging ThemesCatalinaSaavedraNo ratings yet

- DOST Nation BuildingDocument39 pagesDOST Nation BuildingAnonymous Fug5dYNo ratings yet

- Example Research Paper in PhysicsDocument8 pagesExample Research Paper in Physicsadgecibkf100% (1)

- A Systematic Review of The Use of Virtual Reality in EducationDocument6 pagesA Systematic Review of The Use of Virtual Reality in Educationapi-688059491No ratings yet

- Some Thoughts On What It Takes To Produce A Good PHD ThesisDocument23 pagesSome Thoughts On What It Takes To Produce A Good PHD ThesisRubén Bresler CampsNo ratings yet

- 20 April 2022 - UTeM - Effective Vetting and Moderation Process For Creating High-Quality Assessment ItemDocument45 pages20 April 2022 - UTeM - Effective Vetting and Moderation Process For Creating High-Quality Assessment Itemadie adNo ratings yet

- Task 2 Writing SamplesDocument35 pagesTask 2 Writing SamplesmaryamNo ratings yet

- Howe Gonzaga 0736M 10100Document34 pagesHowe Gonzaga 0736M 10100vcautinNo ratings yet

- DP Naskah+6 V1.1 Ilham+Discovery DOI Hal+26-33 FIX HATAMDocument8 pagesDP Naskah+6 V1.1 Ilham+Discovery DOI Hal+26-33 FIX HATAMInternational Journal of Assyfa ResearchNo ratings yet

- (Anticholinergic Drugs and Risk of Dementia) Case Control 1Document24 pages(Anticholinergic Drugs and Risk of Dementia) Case Control 1fina nisaNo ratings yet

- Thesis Book PDFDocument6 pagesThesis Book PDFaflobjhcbakaiu100% (2)

- What Behavioral Predictions Might You Make If You Knew That An Employee HadDocument8 pagesWhat Behavioral Predictions Might You Make If You Knew That An Employee HadBarby Angel100% (2)