Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Issue of Deciphering Carian

Uploaded by

bboyflipperOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Issue of Deciphering Carian

Uploaded by

bboyflipperCopyright:

Available Formats

THE ISSUE OF DECIPHERING CARIAN

1. The Carian language is a pocket of residual obscurity in the ancient eastern Mediterranean

world. Most of what is known of Carian has been found either in Egypt, thanks to numerous

mercenaries who lived there circa the middle of the first millenium BCE, or in Greek texts.

Paradoxically, Caria itself has not revealed much about Carian and even less that can be easily

used to investigate or understand Carian. About 170 Carian inscriptions have been found in

Egypt and published, as noted in Adiego (2007:17), and more are known to exist but have not

been published yet.

On the whole, the assignment of these inscriptions to Carian relies mainly on two features:

(1) They are poorly understood and (2) They are written in a set of alphabets sharing a

number of graphic pecularities, not to say oddities. Lately, claims have been made about an

alleged definitive decipherment of Carian and about its potentially close affinities with the

Anatolian branch of the Indo-European languages. It will be shown that these claims are

erroneous. On the whole, Carian is rather hard to read even when one knows what to find, so

it is little wonder that this language has kept its secrets for so long.

2. In our opinion, a real decipherment passes several basic criteria with success: (1) It shows

how the graphic system works, (2) It provides glosses or translations of the inscriptions. It can

be further added that preferably: (3) The underlying language should be proved to be identical

or close to another known language, (4) The decipherment should help understand how the

graphic system evolves with the passage of time, from one stage to another, or from one

language to another. These criteria are met by other decipherments: Egyptian hieroglyphs are

a complex hyper-alphabetic system that was invented for and used for writing the different

linguistic synchronies that are ancestor to the Coptic dialects, Linear B is an approximative

syllabic system used to write an archaic dialect of Greek but quite obviously not designed to

write this dialect originally, etc. To put it simple and short, a decipherment is expected to

increase in considerable and exponential proportions the understanding of the language which

is supposed to be deciphered. And the reverse perspective is that a decipherment can hardly

succeed until the underlying language is not identified with some security and certainty.

As regards the decipherment of Carian that we propose, it will be shown that:

(1) Carian, or at least Carian as attested in many of the inscriptions assigned to Carian, is

not a separate language but a dialect of the Hurrian language. It is possible that more

than one language are currently lumped together as Carian. This can be elucidated only

after all the inscriptions are fully understood.

(2) The graphic system is a near strictly consonantal system, which only marginally writes

(long) vowels. The Carian alphabet is therefore close to the original Semitic prototype.

(3) Most of the phonetic values are those of the original Semitic prototype.

One hindrance in the understanding of Carian is that inscriptions were scribbled rather than

written and they are often somewhat damaged or partially erased. Another hindrance is that

we cannot fathom the potential distortions introduced by the compilers to the originals.

3.Adiego (2007:166-204), who claims to have deciphered Carian, divides the history of the

decipherment of Carian in three periods or approaches:

- the semi-syllabic approach, from 1887 to 1949,

- the Greeco-Phoenician alphabetic approach,

- the Egyptian approach, since 1972.

The first work on Carian is due to Archibald H. Sayce in 1887. It is quite amazing that this

work on Carian is the first one and at the same time it is not far from being the only one in

more than 130 years that contains relevant and correct information on Carian. Sayce made the

correct assumption that the Carian alphabet must share values with the Greek one. He also

made the exact observation that the letter <w>, which is in fact bta, must be of genitival

character, a typical Hurrian feature (Cf. -wi). Adiego (2007:170) assesses Sayce's contribution

as follows: the failure of his decipherment and the dilettantism of many of his proposals.

This sounds awesome and undeservedly severe. The truth is that nearly everything that was

written in the 130 years after Sayce is close to useless and the only works with practical value

are the compilations of inscriptions.

After Sayce, the ominous Ferdinand Bork managed to spread his influence in one more

field with Carian studies, which lead to the semi-syllabic approach. The Carian alphabet was

supposedly a mixed system with alphabetic and syllabic signs. Bork succeeded in poisoning

the mind of Friedrich, who should nevertheless be remembered as a great scholar. Friedrich

tried to simplify and make sense out of Bork's draft. The comments of Adiego (2007:172)

about Bork's are worth reading and pondering: His analyses are totally arbitrary. Similarly,

the meanings he attributes to the words are capricious. or Needless to say, all these

speculations, based on an invalid decipherment and a nonexistent linguistic family, have been

superseded. Diakonov (1971:20) likewise states that Bork's grammatical analyzes are only

interesting for the historical study of science. It took decades until the 1950ies to get rid of

that semi-syllabic fancy invented by Bork.

In 1949, a very long inscription was found in Kaunos and with only fewer than 30 signs, it

showed that Carian was written in a strictly alphabetic system. In the following years, most of

the known inscriptions were collected and published, a necessary prerequisite for progress.

The next linguist who tried to decipher Carian was Shevoroshkin. He made it clear that Carian

was indeed alphabetically written but he made no significant advances in the understanding of

Carian in more than thirty years of investigation. Other unlucky contributors were O. Masson,

Y. Otpushchikov, P. Meriggi and R. Gusmani.

In 1972, K. Zauzich, an egyptologist, started to investigate bilingual texts in Carian and

Egyptian. This method opened the third period of decipherment and was further developed by

T. Kowalski in 1972 and then by J. Ray, D. Schrr and I. Adiego, ultimately leading to what

Adiego calls the definitive decipherment of Carian. Unfortunately for Adiego, this method

was not applied correctly. As will become rapidly clear, Adiego's approach must be discarded

nearly completely and a fourth period must be added corresponding to a real and definitive

decipherment of the language, which we propose to initiate in the following pages. In all

cases, Adiego's claim to have deciphered Carian was fairly strange as he was still about

completely unable to translate any single sentence or inscription written in Carian. Is it not

troublesome or intriguing that a so-called decipherment does not increase the understanding

of the language which is supposed to be deciphered? How comes that the deciphered words

cannot be compared and translated into the Anatolian languages if Carian is a close relative of

them or even one of them? In fact, Adiego's pseudo-decipherment is a blind and meaningless

transliteration of the Carian alphabet based on erroneous identifications of the letters. The

system of transcription used in Adiego (2007:21) is thoroughly inadequate. Only the first

letter <A> is correct. The rest is worthless. Masson (1978:10) was actually much closer to the

truth.

4. The principle of the Egyptian method is to look for equivalents in the Carian inscriptions

of the Person names which are cited in the Egyptian counterparts of bilingual texts. In theory,

this method should lead to a secure identification of the phonetic values of Carian letters. A

simple example will show the wrong and the right way to apply the method. We will deal

with Memphis 7 in Adiego (2007:40):

O OO Od dd d| || || || |A AA AO OO O O OO Od dd dA AA A1 11 1A AA A Y YY YO OO O| || |A AA A

Memphis 7 (Cf. Masson-Yoyotte 1956)

This inscription is written from right to left on a funerary stela. Adiego reads the texts as

being <tamou tanai qarsio> and makes this comment: The stela provides an Egyptian

inscription that also mentions the dead man T3j-p-jm-w son of T3[...]. The correspondence to

the Carian text is evident: tamou, son of tanai. No less than evident.

A first reaction is to doubt that tamou could be the same as Egyptian T3j-p-jm-w: this

seems to stand for a reconstruction like *[ajpimu]. How comes the -p- has disappeared in

tamou? Our decipherment is <t_a_n_s_u t_a_n_a__w _a_b_m__w>. The name of the

deceased man is not the first word but the last. According to us, the inscription reads:

*[taanusau taaniaiwa abimuiwa] I did [the stela] for abimu, the Taaniai [Tanaite].

The inscription is probably complete as the last letter is <w(a)> the Dative case-marker. The

conclusion is that the Carian alphabet is a typically consonantic alphabet with a defective

writing of vowels. And another conclusion is that the Ray-Schrr-Adiego system cannot be

accepted but for the letter <A>. Although the Carian alphabet reveals some unexpected

values, it remains coherent with the original Phoenician and Greek values. Adiego (2007:194)

lists eight words found in bilinguals which are supposed to bolster his own approach. The

only correct one is the fragmentary equivalence of one syllable in the fourth one. All the rest

is quite incredibly wrong... Whatever the opinio communis may be and whatever Melchert or

Adiego (2007:4) may think, Carian is certainly not a member of the Anatolian branch of PIE.

Carian can be recognized as Hurrian, instantly: -usau P1sg Past, -wa Dative and -i

Ethnonymic formative. There is no doubt that a correct decipherment makes it crystal clear

that Carian has considerable affinities with Hurrian. It can be noted that cuneiformic <> in

Hurrian is rendered as /s/ in the Carian alphabet. This situation is the same as in Hittite.

It can be further noted that more than 10 inscriptions in Abydos contain the name of the

god R <A |> *[ria]

1

but this has remained completely unnoticed so far. For example:

Abydos 32 (Friedrich 1932 Nr 25)

This inscription, from right to left, contains two instances of the name of the god R

*[ria] on the first line. Adiego (2007:91) disregards the second word-separator in order to

1

Cf. Neb-Mat-R <ni-im-mu--ri-a> Mitanni Letter.

read a well-known Carian name. But this cleanly separated word is clearly the God R

*[r(i)a]. After all, it is little wonder that visitors or pilgrims in the temple of Abydos wrote

the name of the God R on the walls...

5. In the next section, we will deal with the inscriptions in Abydos. Readers interested to see

the original drawings and ornemental locations of the inscriptions are advised to read Adiego

(2007:17-165), who made a very heavy work of realistic compilation. We keep the principle

adopted by Adiego of taking the towns as criterion of classification. Our intention is not to

duplicate Adiego's (2007) book but to show how the real decipherment of Carian works. For

that matter, we have not tried to translate all inscriptions included in Adiego (2007), all the

less so as many inscriptions are not cited or represented in their original form but in the

erroneous transliteration of Adiego, of which only the reading of <A> can be kept.

On the whole, the alphabetic scripts in these Carian inscriptions are instable and several

different varieties of alphabet seem to be coexisting. The instability of the script and the

nature of the inscriptions, which are in fact graffiti, increase the difficulty of securely

deciphering most of them. It can nevertheless be noted that the contents of the graffiti is rather

repetitive and they appear to be different arrangements of the same words in many cases,

often dealing with gifts to the god R. Thanks to this feature, some words are frequent and

help to identify the values of letters in each inscription.

The direction of writing is from right to left unless indicated otherwise.

Some inscriptions seem to be written in pure Hurrian rather than Carian: especially

Abydos 7, 27, 29, 32, 33, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39. In this subset of inscriptions with pure Hurrian

features, letters A, Y and F are often used to mark vowel length and geminates are rather often

indicated, especially -nn-. The words are often separated by a vertical line. The letter *[n] <| || |

V VV V> sometimes has a particular shape. *[] is often written like a circle <O OO O> . The letters *[g]

< > and *[q] <- -- -> seem to be distinguished. Other inscriptions indicate vowel length: Abydos

8, 9, 10, 18, 19. They nevertheless are not clearly written in Hurrian. *[r] is written < > in

this latter set of inscriptions.

Several groups of inscriptions can be sorted out:

- F is *[w], *[n] is <1 11 1> in Abydos 2, 3, 13, 14, 15, 31.

- F is *[w], *[n] is <| || |> in Abydos 1, 11, 23, 25.

- inverted values: B is *[w] and F is *[b], *[n] is <1 11 1> in Abydos 4, 6.

- inverted values: B is *[w] and F is *[b], *[n] is <| || |> in Abydos 5, 12, 16, 17, 20, 21,

22, 24, 28, 30, 34.

- extremely strange script: Abydos 26.

The complexity and variety of the values and shapes of the letters is quite intriguing. If our

analysis is correct, there may be no fewer than five or six different variants. There is hardly

such a thing as a standard Carian alphabet in Abydos. The situation is much more complex

from this respect than what is found in the archaic Greek alphabets. This suggests several

acquisitions of the original Phoenician alphabet by Hurrian- and Carian-speaking people. It is

not possible to state how much is due to dialectal phonetic differences or to divergent

alphabetic conventions, not to mention the fact that the people, mainly mercenaries, who

wrote these inscriptions may have an imperfect command of writing. It can be noted that the

letter *k is not attested: *q <- -- -> is used. This suggests that Carian, and maybe Hurrian, had

uvular rather than velar stops. Carian also displays a contrast between three series d ~ t ~ ,

which cannot be documented or evidenced for Hurrian.

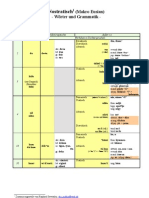

The Carian alphabet used in Abydos has the following letters and phonetic values:

Labial Dental Affricate Palatal Liquid Velar Glottal

Voiced /b/ O OO O O OO O /d/ V VV V A AA A /dz/ // /l/ / // / V VV V /g/

Voiceless /p/ /t/ / // / X XX X /ts/ // 4 44 4 d dd d /q/ - -- - // A AA A

Glottalized // O OO O

/u/ V VV V

Voiced /z/ 1 11 1

/r/ | || | | || | // d dd d O OO O

Voiceless /s/ ! !! !

/x/ 1 11 1 X XX X

Nasals /m/ M MM M /n/ | || | 1 11 1

Glides /w/ | || | /y/ | || | V VV V

Carian Alphabet(s) used in Abydos

represented in left-to-right direction of reading

6. The corpus of inscriptions of Abydos.

Abydos 1 (Friedrich 1932 Nr 1)

The letters are rather clear and well formed. It reads <m s w > *[miasiwii]. The

verbal root is mih-

2

to be standing in front of a god or lord, and it displays a string of

Hurrian suffixes: -h- causative, -wi- Gen., -hi- Adj.. It probably means Reserved to the

priest who introduces the faithful in front of the gods. It can be noted that the letters // H and

/w/ B can hardly be distinguished in most of the inscriptions.

Abydos 2 (Friedrich 1932 Nr 2a)

The last two letters are fused. This inscription is easier to read when compared to Abydos

3. It reads <m an s j / q w aw a b w> *[mn

3

uji

4

qiwiawa

5

biwa] Here is all we bring or

deposit for you. The gifts are presumably for the god R. It can be noted that two letters look

more or less the same [] and [y]. The first <A> lengthens the vowel and does not contain //.

Abydos 3 (Friedrich 1932 Nr 2b)

Two letters are half erased. A possible reading is <m g n [ j] / w aw s b> *[maganni

6

uji

7

iwuawas

8

ab

9

] All the gifts and our things have been taken. It can be noted that the

2

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Wegener (2007: 267).

3

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:167), Wegener (2007:265).

4

Cf. Laroche (1980:240), Wegener (2007:280).

5

Cf. Laroche (1980:145), Wegener (2007:263).

6

Cf. Laroche (1980:164), Wegener (2007:265).

first and sixth letter look the same, that is to say like [] H, but none has this value, they stand

for [] and [] H.

Abydos 4 (Friedrich 1932 Nr 3a)

The inscription is written with inverted values of B/F. Adiego (2007:94) rejects it from his

collection. A possible reading is < l t n / u [?] l b / u j w> *[iltina

10

ulbi

11

uijiwu

12

] He

enters with my other pig, possibly another gift to the temple. There is no clear reason to

reject this inscription as being non Carian.

Abydos 5 (Friedrich 1932 Nr 3b)

The inscription is written with inverted values of B/F. The reading is rather clear <r a n w /

j d / a b / n ts (?)> *[rianiwi jidia

13

abia

14

intsa(w?)

15

] (I ?) made myself poor for the

body and the face of the god R.

Abydos 6 (Friedrich 1932 Nr 3c)

The inscription is written with inverted values of B/F. The reading is fairly clear <r an w j

d a b (?)> *[rianiwi jidia

16

abia

17

(?)] (?) for the body and the face of the god R. It is

unclear whether there is any additional letter.

Abydos 7 (Friedrich 1932 Nr 4)

The inscription is written in a peculiar alphabet, which is closer to the standard Greek and

Phoenician alphabet than other inscriptions. Moreover the language seems much closer to

Hurrian than standard Carian is. It has the Erg. case marker -iz and the past ending -ua,

normally not present in Carian. It may read < r w b z / q w s n / m g nn / b w>

*[urbiiz

18

qiwisinua

19

maganni

20

biwa] The foreigner has deposited the gifts for you. It

seems that the /w/ is used to lengthen the vowel. Cf. Abydos 27, 29.

7

Cf. Laroche (1980:240), Wegener (2007:280).

8

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:267), Wegener (2007:285).

9

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:89), Neu (1988:42), Wegener (2007:258).

10

Cf. Catsanicos (1996).

11

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:278).

12

Cf. Laroche (1980:279).

13

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:73), Wegener (2007:257).

14

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:34), Wegener (2007:248).

15

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Wegener (2007:260).

16

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:73), Wegener (2007:257).

17

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:34), Wegener (2007:248).

18

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:274), Wegener (2007:288).

19

Cf. Laroche (1980:145), Wegener (2007:263).

Abydos 8 (Friedrich 1932 Nr 5a)

The inscription may read <m z a r(?) / m a d s > *[muzri(?)

21

mdisi

22

] Sublime is the

one who makes wise. The letter A is used to express vocalic length.

Abydos 9 (Friedrich 1932 Nr 5a)

Abydos 10 (Friedrich 1932 Nr 5c)

These inscriptions are more or less the same as the previous one. The reading is <m z a r(?)

/ m a d s > *[muzri(?)

23

mdisi

24

] Sublime is the one who makes wise. The fourth letter

may be /w/ or /r/.

Abydos 11 (Friedrich 1932 Nr 6)

The inscription may read <m s q x(?) / l b n r b> *[miawsa

25

q_x_(?)

26

alib

27

niriw

28

]

We stand (giving ?) purified and good. This inscription has nothing to do with person

names. Cf. Abydos 16, 19.

Abydos 12 (Friedrich 1932 Nr 7)

A rather desperate inscription. Maybe from left to right: <? w q w l ?> *[biwa qiwili

29

]

May it be given to you (?).

20

Cf. Laroche (1980:164), Wegener (2007:265).

21

Cf. Laroche (1980:173), Wegener (2007:267).

22

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:163), Wegener (2007:266).

23

Cf. Laroche (1980:173), Wegener (2007:267).

24

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:163), Wegener (2007:266).

25

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Wegener (2007: 267).

26

Cf. Laroche (1980:145), Wegener (2007:263).

27

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Wegener (2007:282).

28

Cf. Laroche (1980:185), Wegener (2007:269).

29

Cf. Laroche (1980:145), Wegener (2007:263).

Abydos 13 (Friedrich 1932 Nr 8a)

The inscription may read <u n b w t an q b s g > *[una

30

biwa atunna

31

qibasgi(ni?)

32

]

The offerer comes to you with love. The article does not appear in this inscription but does

in the next.

Abydos 14 (Friedrich 1932 Nr 8b)

The inscription may read <u n b w t an q w s g n > *[una

33

biwua naxa

34

qiwasgini

35

-

(?)] The offerer comes to you (and gives ?). Something seems to be missing after <>.

Abydos 15 (Friedrich 1932 Nr 9)

The inscription may read <a l w t ? > *[allawi

36

at(?)

37

] (for the ?) love of the lady.

The last word may also be < x> man: for the lady and for the man (?).

Abydos 16 (Friedrich 1932 Nr 10)

The inscription may read <m g nn q x(?) b w > *[maganni

38

q_x(?)

39

biwu(a)] The gifts

(?) for you. The verb is unclear: Cf. Abydos 11, 19: *q x.

Abydos 17 (Friedrich 1932 Nr 11)

The inscription may read <x m b w s x > *[xummi

40

biwa sixu

41

] The altar has been

purified (?) for you. Cf. ihali pure.

30

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:282), Neu (1988:45), Wegener (2007:289-290).

31

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:2485), Neu (1988:45), Wegener (2007:284).

32

Cf. Laroche (1980:145), Wegener (2007:263).

33

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:282), Neu (1988:45), Wegener (2007:289-290).

34

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:175), Neu (1988:44), Wegener (2007:268).

35

Cf. Laroche (1980:145), Wegener (2007:263).

36

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:42), Wegener (2007:246).

37

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:2485), Neu (1988:45), Wegener (2007:284).

38

Cf. Laroche (1980:164), Wegener (2007:265).

39

Cf. Laroche (1980:145), Wegener (2007:263).

40

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:113).

41

Cf. Laroche (1980:221), Wegener (2007:276).

Abydos 18 (Friedrich 1932 Nr 12)

The inscription may read <m a n(?) x n(?) q b> *[mn

42

axi-ni(?)

43

qibu(b)

44

] This the

man gave. The next inscription confirms the reading <n>.

Abydos 19 (Friedrich 1932 Nr 13a)

The inscription may read <r j n w (s?) x n(?) q b> *[rijaniwi yidia(?)

45

axi-ni(?)

46

gibu(b)

47

] For the body of R the man gave. It makes more sense to interpret <s> as <y d>.

Note that R is *[rija] not [ria] as in Abydos 5, 6. Adiego (2007:86-7) repeatedly reads the

name of R as being a Person name *tamosi, in his system.

Abydos 20 (Friedrich 1932 Nr 13b)

The inscription is unclear and may read <r j n w m n q x l b w> *[rijaniwa man

48

q_x_l

49

biwa (or iwu ?)] For R may this be given for you (?).

Abydos 21 (Friedrich 1932 Nr 14)

The inscription may read <t j n r r j n w j(?) d(?) (?)> *[taija

50

niri

51

rijaniwi jidia

52

ai(?)

53

] beautiful (?) and good is the gift for the body of R.

Abydos 22 (Friedrich 1932 Nr 15)

The first line of the inscription is in a desperate state. The second line may read <r j n w m

n q x l b w> *[rijaniwa man

54

q_x_l

55

biwa] For R may this be given for you (?).

42

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:167), Wegener (2007:265).

43

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:251), Wegener (2007:282).

44

Cf. Laroche (1980:145), Wegener (2007:263).

45

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:73), Wegener (2007:257).

46

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:251), Wegener (2007:282).

47

Cf. Laroche (1980:145), Wegener (2007:263).

48

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:167), Wegener (2007:265).

49

Cf. Laroche (1980:145), Wegener (2007:263).

50

Cf. Laroche (1980:249).

51

Cf. Laroche (1980:185), Wegener (2007:269).

52

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:73), Wegener (2007:257).

53

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:253), Wegener (2007:284).

54

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:167), Wegener (2007:265).

Abydos 23 (Friedrich 1932 Nr 16)

The inscription may read <? n/l x b d a l i> *[man(?)

56

xibadi allai

57

] Here is (?) Queen

Hebat. This inscription is not considered a definitely Carian inscription although the letters

look Carian. The last letters may also be interpreted as <b d a l i> *[abd-ali]. In that case, it

would be Semitic not Carian, but this does not seem probable.

Abydos 24 (Friedrich 1932 Nr 17)

The inscription may read <n w z> *[naiawza

58

] We will/want to sit.

Abydos 25 (Friedrich 1932 Nr 18)

The inscription may read <(?) a r a b > *[(?) ari

59

abia

60

] (?) gives for the face (of

R). This is certainly not the Person name Arli as suggested in Adiego (2007:89).

Abydos 26 (Friedrich 1932 Nr 19)

The alphabet is extremely peculiar. The inscription may read <r (?) n w a b (?) d (?) q b r

w> *[ri(?)aniwi awia

61

yidia

62

qibiri

63

iwu

64

] For the face and body of R they have

brought (these) things.

Abydos 27 (Friedrich 1932 Nr 20)

The inscription may read <(?) m w s m g n u (?) r > *[a(?)mmawsa

65

maganniuura

66

]

We have come (?) with presents. This inscription may be written in Hurrian. Cf. Abydos 7,

29 for the same use of word separators and the peculiar <s> letter.

55

Cf. Laroche (1980:145), Wegener (2007:263).

56

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:167), Wegener (2007:265).

57

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:42), Wegener (2007:246).

58

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:175), Neu (1988:44), Wegener (2007:268).

59

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:52), Neu (1988:41), Wegener (2007:248).

60

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:34), Wegener (2007:248).

61

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:34), Wegener (2007:248).

62

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:73), Wegener (2007:257).

63

Cf. Laroche (1980:145), Wegener (2007:263).

64

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:267), Wegener (2007:285).

65

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1987:46-47), Wegener (2007:247).

Abydos 28 (Friedrich 1932 Nr 21)

The inscription may read from left to right <(?) r (?) w q n s j m> *[a(?)ri

67

biwa

qunsmi

68

] Given to you kneeling. This inscription may be written in Hurrian. Cf. Abydos 7,

for the same use of word separators and the peculiar <s> letter. The direction of reading given

in Adiego (2007:90) or Friedrich (1932:94) is wrong in our opinion. The shape of <n> and

<y> indicates left to right writing. The shape of <r> is ambiguous as it can be written head-

first or head-behind.

Abydos 29 (Friedrich 1932 Nr 22)

A very difficult inscription. It may read from left to right <(?)(?) (?) : n b q r s : x r u s t /

t l (?)> *[paiwu

69

nubi

70

-qurus

71

xursi-a

72

tal-(usaw?)

73

] My head ten thousand times for

the hubruhi (I have purified ?). This inscription is most certainly written in Hurrian. Cf.

Abydos 7, 27. The inscription seems to reflect an inversion between <> and <t>. Adiego

(2007:90) has cut off the second line for some unknown reason.

Abydos 30 (Friedrich 1932 Nr 23)

The inscription may read from left to right <t l x w (?) q n ts (?) > *[talix(?)

74

iwu(?)

75

qunts(?)

76

] The affair has been purified kneeling (?). Adiego (2007:94) holds this inscription

to be possibly Greek.

Abydos 31 (Friedrich 1932 Nr 24)

A difficult inscription with many gaps. It may read <(? ?) w (?) g n g > *[rijaniwa

maganni(?)

77

agi(?)

78

] For the god R a beautiful present (?).

66

Cf. Laroche (1980:164), Wegener (2007:265).

67

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:52), Neu (1988:41), Wegener (2007:248).

68

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:155), Neu (1988:43), Wegener (2007:264).

69

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:192), Wegener (2007:270).

70

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:187), Neu (1987:44), Wegener (2007:270).

71

Cf. Laroche (1987:156), Wegener (2007:264).

72

Cf. Laroche (1987:109).

73

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Wegener (2007:282).

74

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Wegener (2007:282).

75

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:267), Wegener (2007:285).

76

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:155), Neu (1988:43), Wegener (2007:264).

77

Cf. Laroche (1980:164), Wegener (2007:265).

Abydos 32 (Friedrich 1932 Nr 25)

A rather long and complex inscription with a peculiar alphabet. The inscription may read

<[1.] n (?) w a n s a : r a : (?) w (?) z : r a : q p w [2.] (? ?) a d z a : n s s>

*[nau(s?)w

79

(?) nisia : ria : naiwaz

80

(?) : ria : qipi

81

iwu

82

/ (? ?) : nisi su(yi ?)] We

have put his gain on the ground : (for) the god R : our gift : (for) the god R is given things :

(? ?) : all is (his) gain. The form *[nau(s?)w (?)] may be a metathesis of *[nausawa].

The second line may read <muzri mdizia> Sublime is the one who makes wise (?). Cf.

Abydos 8, 9, 10. The inscription contains twice the name of the god R *[ria], a feature that

has remained unnoticed. Adiego (2007:91) overruns the second word-separator in order to

read a well-known Carian name which actually starts with R *[r(i)a].

Abydos 33 (Friedrich 1932 Nr 26a)

A short but uneasy inscription. It may read <t a j > *[tiaja

83

] They are numerous (?).

Abydos 34 (Friedrich 1932 Nr 26b)

Another short but uneasy inscription. It may read <t a (?) w> *[tia(?)

84

iwu

85

] Things

(that is to say: gifts) are numerous (?).

Abydos 35 (Friedrich 1932 Nr 27)

An inscription with a peculiar alphabet. It may read <r a w m g

86

: m (dz?) l > *[riawi

magi : mudzili

87

] The desire (?) of the god R : may it or he/she be righteous (?).

Abydos 36 (Friedrich 1932 Nr 28)

78

Cf. Laroche (1980:249).

79

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:175), Neu (1988:44), Wegener (2007:268).

80

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:175), Neu (1988:44), Wegener (2007:268).

81

Cf. Laroche (1980:145), Wegener (2007:263).

82

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:267), Wegener (2007:285).

83

Cf. Laroche (1980:260), Wegener (2007:285).

84

Cf. Laroche (1980:260), Wegener (2007:285).

85

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:267), Wegener (2007:285).

86

Cf. Laroche (1980:164).

87

Cf. Laroche (1980:173), Wegener (2007:267).

A difficult inscription. It may read <(?) d j n r b l p> *[tadaji

88

niribilip

89

] [Done] well

with love (?). This inscription seems to be closer to Hurrian.

Abydos 37 (Friedrich 1932 Nr 29)

This inscription may read <(?) b w z : n t b l (?) s b> *[gibawza

90

(?) : nautib

91

alu

92

siib

93

] We put [our gift], it was there, [then] taken away and entered [the temple].

Abydos 38 (Friedrich 1932 Nr 30)

This inscription may read <x(?) m t (?) j u z> *[xummi

94

tijuauza(?)

95

] We spoke in

front of the altar (?).

Abydos 39 (Murray 1904)

This inscription may read <(?) r d l l> *[kiri

96

dilla] We are free or *[sari

97

dilla] We

desire.

7. Another interesting inscription to look at is the Kaunos bilingual. Of this document,

Melchert (2004:65) boldly asserts that:

The new CarianGreek bilingual from Kaunos has shown conclusively the essential validity of

the RayAdiegoSchrr system, while also confirming the suspicion of local variation in the use

of the Carian alphabet.While some rarer signs remain to be elucidated, the question of the

Carian alphabet may be viewed as decided.

It will be shown below that this claim is absurd hogwash.

The new bilingual has not led to immediate equally dramatic progress in our grasp of the

language.

88

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:2485), Neu (1988:45), Wegener (2007:284).

89

Cf. Laroche (1980:185), Wegener (2007:269).

90

Cf. Laroche (1980:145), Wegener (2007:263).

91

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:175), Neu (1988:44), Wegener (2007:268).

92

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Wegener (2007:282).

93

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:223), Wegener (2007:276).

94

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:113).

95

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:267), Wegener (2007:285).

96

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Neu (1988:43), Wegener (2007:263).

97

Cf. Catsanicos (1996), Laroche (1980:215), Neu (1988:44), Wegener (2007:275).

Decipherment without any simultaneously improved understanding of the Carian

language is a conspicuous feature of the RayAdiegoSchrr-cum-Melchert system.

One reason for this is that the Greek text of the Kaunos Bilingual is a formulaic proxenia decree,

while the corresponding Carian is manifestly quite independent in its phrasing of what must be

essentially the same contents.

It will be shown below that the Carian text is very close in its contents to the Greek text.

The Kaunos Bilingual has provided welcome confirmation of the view that Carian is an Indo-

European Anatolian language, and indeed, of the western type of Luvian, Lycian, and Lydian.

However, one cannot speak of a complete decipherment until there are generally accepted

interpretations of a substantial body of texts a stage not yet fully attained. This remark applies

even to the new bilingual, as one can easily confirm by reading the competing linguistic

analyses in Blmel, Frei, and Marek 1998. The following very sketchy description of the

language must therefore be taken as highly provisional!

To say the least.

So, what is the Kaunos Greek-Carian bilingual? What has been retrieved of the original

document is now three reassembled parts, which contain 26 lines of letters, the first 18 lines

are Carian and the last 7 are written in Greek. A number of inferences and descriptive remarks

can be made:

- According to the first lines of the Greek text, which seem to be missing no letters, the

Carian text misses about two letters at the end in the 13 first lines.

- The 18

th

line of the Carian text occupied only the left part of the line, which suggests that

the direction of writing was from left to right.

- What is left of the Carian text (18 lines) is much longer than what is left of the Greek part

(7 lines), so that it is unclear whether the Carian and Greek sections originally were a

strictly equivalent translation of one another.

The 5 first lines of Greek are rather well-preserved and we will compare them to the 6 first

lines of Carian. One recurrent question about so-called bilinguals is to determine whether

they are bilingual in the weak or the strong sense: Are they a coarse and remotely allusive

equivalent of one another or are they a close and nearly literal translation of one language into

the other? It will be shown below that the Kaunos bilingual most probably was a bilingual in

the strong sense, contrary to what Melchert (2004) believes: in fact, to judge from the first

lines of each language, the corresponding Carian is manifestly quite equivalent in its phrasing

of what must be essentially the same word-for-word contents in the Greek part. This is only

slightly obscured by the fact that the Greek Person names seem to be half-translated into

Carian, instead of being just rephonemicized in Carian.

According to Adiego (2007:154-156), the first lines of Carian are :

1. V VV V | || | V V V V O O O O | || | 1 11 1 j jj j ] ]] ]

D U H = *diui it is said [that]

Translates KA 5.18 EDOE, the first word of the Greek text.

Q U N H = *Qaunihi- (by) the Kaunians

NB: < V V V V > is better read < O OO O | || | 1 11 1>. Translates KA 5.18 KAVNOIS

M Z X = *muzu-xi = [this] has been placed

This refers to the bilingual itself.

[x x] = (probably) *u[rbi] foreign

Translates KA 5.23 OENOV

2. 1 11 1 ! !! ! | || | V VV V A AA A A AA A 1 11 1 d dd d (:) (:) (:) (:)

X = axi-a for the man

Continued translation of KA 5.23 OENOV

S M - (R?) L = summi-(r?)ili [and for the] hand-worker

Translates KA 5.19-20 HMIO / POU

A T N H = Atenai-xx Athenian(s)

Translates KA 5.23 [A]

3. A AA A A AA A 1 11 1 A AA A | | | | ! !! ! d dd d V VV V A AA A A AA A ! !! !

T A N A W S = tnu-awsa we have done [this]

D T A S x x = adars-xx for [our] friends

Both words translate KA 5.24 [A]IEVEPETA

4. O OO O | || | O OO O 1 11 1 O O O O ! !! ! 1 11 1 ! !! ! | || | A AA A | || |

L U K L S = Li-kles

Translates KA 5.21 VIKEOV

A S U T W x x = As-t-w-xx (Hippo-sthenos)

Seems to translate KA 5.21 IOHNOV

The Carian seems to be a derivative of (Hurrian) au horse.

5. A A A A 1 11 1 A AA A | || | ! !! ! V VV V | || | A AA A | || | A AA A ! !! !

N K L W S H = Nikolewas-ii Nikolewa-ian

Adiego (2007:155) reads **Nikoklea, but this seems to exist neither in Greek nor Carian.

L U K R S = Li-kras-xx

Translates KA 5.22 VIKPA-(T?)

6. O OO O | || | O OO O 1 11 1 O O O O ! !! ! 1 11 1 ! !! ! A AA A | || | 1 11 1

L U K L W/S(?) A S = Li-klews

A T N H x x = Atenai-xx Athenian

The Carian first 6 lines translate as: It is declared that by the Qaunians [this] has been

placed on behalf of the foreign man and the hand-worker, from Athens. We have done [this]

[for our] friends: Li-kles As-t-w-xx(?), son of Nikolewa, and Li-kras-xx(?) Li-klews,

son of Athena[io].

A few letters do not seem to be distinguished as they should:

- A [a] (not **[n]) ~ 1 11 1 [n] (not **[a]) ~ 1 11 1 [k],

- A ~ A AA A [t] ~ | || | [t],

A AA A [t] ~ A AA A or O OO O [l] ~ O OO O []

For example, Athena-(i) is written as < A AA A A AA A 1 11 1 d dd d > and < A AA A | || | 1 11 1 >.

The document makes a very clear distinction between the consonant [w] < E > and the long

vowel [] < | || |, | || | >. Short vowels are conspicuously not indicated, as in Abydos.

7. As a conclusion of this short sketch, we will reaffirm a few core inferences:

- The definitive RayAdiegoSchrr-cum-Melchert pseudo-decipherment is bogus.

- The Carian language is in fact a dialect of Hurrian.

- Carian is written in a set of near strictly consonantal alphabets, close to Semitic practices.

We are confident that future research on Carian can only bolster, support and reinforce

these conclusions.

References

Adiego, Ignacio-Javier

2007 The Carian Language. Leiden, London: Brill.

Bauer, Hans

1936 Die alphabetischen Keilschrifttexte von Ras Schamra. Berlin: Walter de

Gruyter.

Bush, Frederic William

1964 A Grammar of the Hurrian Language. Ph.D. dissertation, Brandeis

University, Department of Mediterranean Studies.

Catsanicos, Jean.

1996 Lapport de la bilingue attua la lexicologie hourrite, in: Jean-Marie

Durand (ed.), Amurru 1, Paris: ditions Recherche sur les Civilisations, pp.

197296.

de Martino, Stefano

1992 Die mantischen Texte. Corpus der hurritischen Sprachdenkmler. I. Ab-

teilung, Texte aus Boazky, 7. Roma: Bonsignori.

Diakonoff, Igor M.

1971 Hurrisch und Urartisch. Mnchen: R. Kitzinger.

Diakonoff, Igor M., and Sergej A. Starostin

1986 Hurro-Urartian as an Eastern Caucasian Language. Mnchen: R. Kitzinger.

Frei, P. and C. Marek

1997 Die karisch-griechische Bilingue von Kaunos. in Kadmos 36:189.

Freu, J.

2003 Histoire du Mitanni. Paris: LHarmattan, collection Kubaba.

Friedrich, Johannes

1932 Kleinasiatische Sprachdenkmler. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

1969a Churritisch, in: B. Spuler (ed.), Altkleinasiatische. Leiden: E. J. Brill, pp.

130.

1969b Urartisch, in: B. Spuler (ed.), Altkleinasiatische Sprachen. Leiden: E. J.

Brill, pp. 3153.

Gelb, Ignace J.

1961 Old Akkadian Writing and Grammar. 2nd edition. Chicago, IL: The Uni-

versity of Chicago Press.

Gragg, Gene

1997a Hurrian, in: Eric M. Meyers (ed.), The Oxford Encyclopedia of Archaeology

in the Near East. New York, NY, and Oxford: Oxford University Press,

3:125126.

1997b Hurrians, in: Eric M. Meyers (ed.), The Oxford Encyclopedia of Archae-

ology in the Near East. New York, NY, and Oxford: Oxford University Press,

3:126130.

2003 Hurrian and Urartian, in: William J. Frawley (ed.), The International

Encyclopedia of Linguistics. 2nd edition. New York, NY: Oxford University

Press, 2:254256.

Haikian, Levon Margareta (Margaret Khaikjan)

1985 Hurritskij i Urartskij Jazyki. Erevan: Akademija Nauk Armjanskoj SSR,

Institut Vostokovednija.

Lambert, W.G.

1982 An early Hurrian Personal Name, in: Revue dassyriologie et darcho-

logie orientale 77:95.

Laroche, Emmanuel

1968 Documents en langue hourrite provenant de Ras Shamra, in: Claude F. A.

Schaeffer (ed.), Ugaritica 5: nouveaux textes accadiens, hourrites, et

ugaritiques des archives et bibliothques prives dUgarit, commentaires des

textes historiques (= Mission de Ras Shamra 16 = Institut franais de

Beyrouth, Bibliothque archologique et historique 80.). Paris: Geuthner, pp.

447544.

1980 Glossaire de la langue hourrite (= Revue Hittite et Asianique, 34/35.). Paris:

ditions Klincksieck.

Macqueen, J. G.

1994 Hurrian, in: R. E. Ascher (ed.) and J. M. Y. Simpson (Coordinating Editor),

The Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics. Oxford, New York, NY,

Seoul, Tokyo: Pergamon Press, 3:1621.

Masson, Olivier

1978 Carian Inscriptions from North Saqqara and Buhen. London: Egypt

Exploration Society.

Masson-Yoyotte

1956 Objets pharaoniques inscription carienne. Le Caire: l'Institut franais

d'archologie orientale.

Melchert, Graig H.

2004 Carian, in: Roger D. Woodard (ed.), The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the

Worlds Ancient Languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp.

6468.

Melikivili, G. A.

1971 Die urartische Sprache. Translated from Russian by Karl Sdrembek. Rome:

Biblical Institute Press.

Moran, William L.

1987 Les lettres dEl-Amarna. Correspondance diplomatique du pharaon. Paris:

ditions du Cerf.

1992 The Amarna Letters. London, Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press.

Neu, Erich

1988 Das Hurritische: Eine altorientalische Sprache in neuem Licht. Abhandlung

der Geistes- und sozialwissenschaftlichen Klasse (Akademie der Wissen-

schaften und der Literatur). Jahrgang 1988, Nr. 3. Main-Stuttgart.

1996 La bilingue Hourro-Hittite de attua, contenu et sens, in: Jean-Marie

Durand (ed.), Amurru 1, Paris: ditions Recherche sur les Civilisations, pp.

189195.

Parmegiani, Neda

2005 Konkordanzen. Corpus der hurritischen Sprachdenkmler. I. Abteilung, Texte

aus Boazky, 10. Roma: CNR.

Schaeffer, F.-A. Claude, Charles Virolleaud, and Franois Thureau-Dangin

1931 La deuxime campagne de fouilles Ras-Shamra (Printemps 1930), Rapport

et tudes prliminaires, (extrait de la revue Syria 1931). Paris: Paul Geuthner.

Sherratt, Andrew (ed.)

1980 The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Archaeology. New York, NY: Crown

Publishers/Cambridge University Press.

Speiser, Ephraim A.

1941 Introduction to Hurrian (= Annual of the American Schools of Oriental

Research, 20). New Haven, CT: American Oriental Society.

Thieme, Paul

1960 The Aryan Gods of the Mitanni Treaties, Journal of the American

Oriental Society 80:301317.

Wegner, Ilse

1995 Hurritische Opferlisten aus hethitischen Festbeschreibungen: Texte fr

ITAR-a(w)uka. Corpus der hurritischen Sprachdenkmler. I. Abteilung,

Texte aus Bogazky, 3/1. Roma: Bonsignori.

2002 Hurritische Opferlisten aus hethitischen Festbeschreibungen: Texte fr

Teub, Hebat und weitere Gottheiten. Corpus der hurritischen Sprach-

denkmler. I. Abteilung, Texte aus Boazky, 3/2. Roma: CNR.

2004 Hurritische Opferlisten aus hethitischen Festbeschreibungen: das Glossar.

Corpus der hurritischen Sprachdenkmler. I. Abteilung, Texte aus Boazky,

3/3. Roma: CNR.

2007 Hurritisch: eine Einfhrung. 2nd edition. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz

Verlag.

Wilhelm, Gernot

1982 Grundzge der Geschichte und Kultur der Hurriter. Darmstadt: Wissen-

schaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

1989 The Hurrians. Translated by Jennifer Barnes, with a chapter by Diana L.

Stein. Warminster: Aris and Philips.

1996 L'tat actuel et les perspectives des tudes hourrites, in: Jean-Marie Durand

(ed.), Amurru 1. Paris: ditions Recherche sur les Civilisations, pp. 175

187.

2004a Hurrian, in: Roger D. Woodard (ed.), The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the

Worlds Ancient Languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp.

95118.

2004b Urartian, in: Roger D. Woodard (ed.), The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the

Worlds Ancient Languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp.

119137.

Zauzich, Karl-Theodor

1972 Einige karische Inschriften aus Aegypten und Kleinasien und ihre Deutung

nach der Entzifferung der karische Schrift. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz.

You might also like

- Cicero's Philippics and Their Demosthenic Model: The Rhetoric of CrisisFrom EverandCicero's Philippics and Their Demosthenic Model: The Rhetoric of CrisisNo ratings yet

- Adiego (Hellenistic Karia)Document68 pagesAdiego (Hellenistic Karia)Ignasi-Xavier Adiego LajaraNo ratings yet

- Nostratic-Words and GrammarDocument8 pagesNostratic-Words and GrammarDavide Montecuori100% (1)

- Black Speech Ork Talk PDFDocument9 pagesBlack Speech Ork Talk PDFRominaNo ratings yet

- Quenya Grammar: General Pronounciation and SymbolsDocument7 pagesQuenya Grammar: General Pronounciation and SymbolsMarcelNo ratings yet

- Carsten, Anne Marie. Karian IdentityDocument8 pagesCarsten, Anne Marie. Karian IdentitywevanoNo ratings yet

- Agreement of Adjectives in QuenyaDocument14 pagesAgreement of Adjectives in QuenyaMarcelNo ratings yet

- German VowelsDocument6 pagesGerman VowelsDavide MontecuoriNo ratings yet

- Troy: City, Homer and TurkeyDocument93 pagesTroy: City, Homer and TurkeyRoderickHenry100% (2)

- Mairs Heroic Greek Names BactriaDocument10 pagesMairs Heroic Greek Names BactriaRachel MairsNo ratings yet

- Speidel 103 PDFDocument5 pagesSpeidel 103 PDFLuciusQuietusNo ratings yet

- Hammond The Koina of Epirus and MacedoniaDocument11 pagesHammond The Koina of Epirus and MacedoniaJavier NunezNo ratings yet

- $ret7jy1 PDFDocument9 pages$ret7jy1 PDFMax RitterNo ratings yet

- Alexander and OrientalismDocument4 pagesAlexander and OrientalismvademecumdevallyNo ratings yet

- Alcman's Partheneion. Legend and Choral Ceremony PDFDocument11 pagesAlcman's Partheneion. Legend and Choral Ceremony PDFDámaris Romero100% (1)

- The Problem of Nomadic Allies in The Roman Near EastDocument95 pagesThe Problem of Nomadic Allies in The Roman Near EastMahmoud Abdelpasset100% (2)

- 86.henkelman - Pantheon and Practice of WorshipDocument39 pages86.henkelman - Pantheon and Practice of WorshipAmir Ardalan EmamiNo ratings yet

- 7 Militarev Afrasian Akkadian DefDocument8 pages7 Militarev Afrasian Akkadian Defobladi05No ratings yet

- Chiliades, Juan TzetzesDocument472 pagesChiliades, Juan TzetzesJuan Bautista Juan LópezNo ratings yet

- Pre GreekDocument34 pagesPre Greekkamy-gNo ratings yet

- Pella Curse TabletDocument3 pagesPella Curse TabletAlbanBakaNo ratings yet

- Kinship Between Burials From Grave Circle B at Mycenae Revealed by Ancient DNA TypingDocument5 pagesKinship Between Burials From Grave Circle B at Mycenae Revealed by Ancient DNA TypingmilosmouNo ratings yet

- Dictionary To The Anabasis, Ehite and MorganDocument312 pagesDictionary To The Anabasis, Ehite and MorganMurilo MoraesNo ratings yet

- BATL062Document19 pagesBATL062Roxana TroacaNo ratings yet

- Men, Goods and Ideas Travelling Over The Sea. Cilicia at The Crossroad of Eastern Mediterranean Trade Network - Schneider 2020Document99 pagesMen, Goods and Ideas Travelling Over The Sea. Cilicia at The Crossroad of Eastern Mediterranean Trade Network - Schneider 2020Luca FiloniNo ratings yet

- SCHMITZ2008Document6 pagesSCHMITZ2008simpletheu100% (1)

- M. West The Writing Tablets and Papyrus From The Tomb II in DaphniDocument20 pagesM. West The Writing Tablets and Papyrus From The Tomb II in DaphnifcrevatinNo ratings yet

- Pre-Greek Loanwords in Greek (Beekes)Document31 pagesPre-Greek Loanwords in Greek (Beekes)TalskubilosNo ratings yet

- A Survey of Toponyms in EgyptDocument894 pagesA Survey of Toponyms in EgyptDr-Mohammad ElShafeyNo ratings yet

- In VerremDocument15 pagesIn Verremahmedm786No ratings yet

- 1986 - Gerard Boter - The Venetus T of Plato PDFDocument10 pages1986 - Gerard Boter - The Venetus T of Plato PDFAlice SilvaNo ratings yet

- Tinker, Tailor, Minoans and Mycenaeans: Soldier, Sailor: AbroadDocument23 pagesTinker, Tailor, Minoans and Mycenaeans: Soldier, Sailor: AbroadPaulaBehin100% (1)

- Parian Marble ChronicleDocument8 pagesParian Marble ChronicleЛазар СрећковићNo ratings yet

- Vernant (1990) The Society of The GodsDocument19 pagesVernant (1990) The Society of The GodsM. NoughtNo ratings yet

- Scylla: Hideous Monster or Femme Fatale?: A Case of Contradiction Between Literary and Artistic EvidenceDocument10 pagesScylla: Hideous Monster or Femme Fatale?: A Case of Contradiction Between Literary and Artistic EvidenceCamila JourdanNo ratings yet

- SUSAN SATTERFIELD. Rome's - Own - Sibyl - The - Sibyllin - BooksDocument266 pagesSUSAN SATTERFIELD. Rome's - Own - Sibyl - The - Sibyllin - Booksrafael_pansaNo ratings yet

- Germanic Personal Names in GaliciaDocument16 pagesGermanic Personal Names in GaliciaVesna ZafirovskaNo ratings yet

- The Aeneid Book VI Lines 295-332, 384-425, 450-476, 847-899Document4 pagesThe Aeneid Book VI Lines 295-332, 384-425, 450-476, 847-899bellelin8No ratings yet

- Draft 006 15jan2008Document39 pagesDraft 006 15jan2008api-3812626No ratings yet

- Bronze Age Tumuli and Grave Circles in GREEKDocument10 pagesBronze Age Tumuli and Grave Circles in GREEKUmut DoğanNo ratings yet

- Whatmough Dialects FootnotesDocument49 pagesWhatmough Dialects FootnotesСтефан ПоповацNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To Classical ArmenianDocument38 pagesAn Introduction To Classical ArmenianAlin SuciuNo ratings yet

- Italian UnificationDocument201 pagesItalian UnificationTarachand PanwarNo ratings yet

- Dares-Dictys - Troia and WilusaDocument101 pagesDares-Dictys - Troia and WilusaEcaterina TaralungaNo ratings yet

- On - Saracens - The - Rawwafah - Inscription - and The Roman Army PDFDocument29 pagesOn - Saracens - The - Rawwafah - Inscription - and The Roman Army PDFygurseyNo ratings yet

- Indo-European Lexicon: Pokorny Master PIE EtymaDocument44 pagesIndo-European Lexicon: Pokorny Master PIE EtymalamacarolineNo ratings yet

- Journal of The American Oriental Society Volume 119 Issue 2 1999 (Doi 10.2307/606114) Christine Lilyquist - On The Amenhotep III Inscribed Faience Fragments From MycenaeDocument7 pagesJournal of The American Oriental Society Volume 119 Issue 2 1999 (Doi 10.2307/606114) Christine Lilyquist - On The Amenhotep III Inscribed Faience Fragments From MycenaeNițceValiNo ratings yet

- Reviewed Work Hethitische Kultmusik Eine Untersuchung - Monika SchuolDocument3 pagesReviewed Work Hethitische Kultmusik Eine Untersuchung - Monika SchuolTarek AliNo ratings yet

- Phaistos Disk and Its Meaning: A New ApproachDocument15 pagesPhaistos Disk and Its Meaning: A New ApproachWilson Javier Puigdevall HerediaNo ratings yet

- GUÐRÚNARKVIÐA III (The Third Lay of Gudrún)Document3 pagesGUÐRÚNARKVIÐA III (The Third Lay of Gudrún)H_WotanNo ratings yet

- G R Tsetskhladze-Pistiros RevisitedDocument11 pagesG R Tsetskhladze-Pistiros Revisitedruja_popova1178No ratings yet

- Nou 41 SmethurstDocument11 pagesNou 41 SmethurstVictor Cantuário100% (1)

- Minos of Cnossos. King, Tyrant and Thalassocrat.Document194 pagesMinos of Cnossos. King, Tyrant and Thalassocrat.Jorge Cano MorenoNo ratings yet

- Old Phrygian Inscriptions From Gordion: Toward A History of The Phrygian Alphabet1Document53 pagesOld Phrygian Inscriptions From Gordion: Toward A History of The Phrygian Alphabet1waleexasNo ratings yet

- Pindars Ninth Olympian PDFDocument12 pagesPindars Ninth Olympian PDFi.s.No ratings yet

- Helene Whittaker-Mycenaean Cult Buildings PDFDocument349 pagesHelene Whittaker-Mycenaean Cult Buildings PDFIoana Inoue100% (1)

- New Messapic InscriptionsDocument13 pagesNew Messapic InscriptionsbboyflipperNo ratings yet

- The Messapic Klaohizis FormulaDocument10 pagesThe Messapic Klaohizis FormulabboyflipperNo ratings yet

- The Messapic Klaohizis FormulaDocument10 pagesThe Messapic Klaohizis FormulabboyflipperNo ratings yet

- Some Famous Indo-European Sound LawsDocument2 pagesSome Famous Indo-European Sound LawsbboyflipperNo ratings yet

- On Triballic in AristophanesDocument2 pagesOn Triballic in AristophanesbboyflipperNo ratings yet

- Caucasian and Near Eastern Studies XIII - Armenian 1Document8 pagesCaucasian and Near Eastern Studies XIII - Armenian 1bboyflipperNo ratings yet

- Some Famous Indo-European Sound LawsDocument2 pagesSome Famous Indo-European Sound LawsbboyflipperNo ratings yet

- The Problem of Identification of The Proto-ArmeniansDocument37 pagesThe Problem of Identification of The Proto-ArmeniansbboyflipperNo ratings yet

- The Messapic Klaohizis FormulaDocument10 pagesThe Messapic Klaohizis FormulabboyflipperNo ratings yet

- Outline History of Asia MinorDocument7 pagesOutline History of Asia MinorbboyflipperNo ratings yet

- The Thracian Pig DanceDocument11 pagesThe Thracian Pig DancebboyflipperNo ratings yet

- Carians in SardisDocument6 pagesCarians in SardisbboyflipperNo ratings yet

- Pamphylian NotesDocument22 pagesPamphylian NotesbboyflipperNo ratings yet

- An Archaic Inscription From SamothraceDocument6 pagesAn Archaic Inscription From SamothracebboyflipperNo ratings yet

- Alphabets Scripts Ciphers & Gematria (v1.0)Document45 pagesAlphabets Scripts Ciphers & Gematria (v1.0)galaxy511197% (34)

- 1 - Arab Mein Butt Parasti PDFDocument18 pages1 - Arab Mein Butt Parasti PDFMaliha KhanNo ratings yet

- Chatura February 2013Document169 pagesChatura February 2013sagar_lal100% (1)

- AccidentDocument1 pageAccidentMahendra DashNo ratings yet

- Meletios Pegas On The EucharistDocument51 pagesMeletios Pegas On The EucharistEvangelosNo ratings yet

- Constellation PresentationDocument13 pagesConstellation PresentationGary Rose100% (2)

- Cobas Pro GLU, AU, Chol Tot, TG Mei 2022-Gusti AdheleidaDocument24 pagesCobas Pro GLU, AU, Chol Tot, TG Mei 2022-Gusti Adheleidagusti adheleidaNo ratings yet

- Musical Arts of The Pamirs - V3 - RUSDocument620 pagesMusical Arts of The Pamirs - V3 - RUSfredNo ratings yet

- Shantipath - BhaktachintamaniDocument66 pagesShantipath - BhaktachintamaniLoyadham ParivarNo ratings yet

- LaTeX Tabelas de SímbolosDocument6 pagesLaTeX Tabelas de SímbolosLuiz CamargoNo ratings yet

- The Sounds of His Coming From KJM To Maam AbbyDocument9 pagesThe Sounds of His Coming From KJM To Maam AbbyAbby Jamoner GabutinNo ratings yet

- QuickbetaDocument23 pagesQuickbetabobdemonNo ratings yet

- Greek Differences PDFDocument2 pagesGreek Differences PDFe2a8dbaeNo ratings yet

- Atrevida: Niche BassDocument2 pagesAtrevida: Niche BassJuan Carlos Beleño100% (1)

- Catalogo Tecnored Conductor Al.Document5 pagesCatalogo Tecnored Conductor Al.Marioyfernanda Guerra MuruaNo ratings yet

- ALT CodesDocument12 pagesALT CodesAmir RahmanNo ratings yet

- Greek: Practice WorksheetDocument17 pagesGreek: Practice WorksheetOana X TodeNo ratings yet

- November 2006Document141 pagesNovember 2006api-3750896No ratings yet

- Akhbar Kay Baray Main Sawal JawabDocument63 pagesAkhbar Kay Baray Main Sawal JawabIslamic LibraryNo ratings yet

- Lambdans 1962 PrimierDocument6 pagesLambdans 1962 Primiersigma_gamma_lambda1962No ratings yet

- Battle of MarawiDocument3 pagesBattle of MarawiKaren OnggayNo ratings yet

- Communications and Broadcasting in TeluguDocument14 pagesCommunications and Broadcasting in TeluguGottimukkala MuralikrishnaNo ratings yet

- De Thi de Thi Vao Lop 10 Mon Tieng Anh Chuyen Truong THPT Chuyen Le Hong Phong Nam Dinh Nam Hoc 2017 2018 Co Dap AnDocument5 pagesDe Thi de Thi Vao Lop 10 Mon Tieng Anh Chuyen Truong THPT Chuyen Le Hong Phong Nam Dinh Nam Hoc 2017 2018 Co Dap AnPẹt Pẹt Pula PulaNo ratings yet

- Greek Pronunciation 2008Document14 pagesGreek Pronunciation 2008MuriloNo ratings yet

- Nino Precioso in CMDocument2 pagesNino Precioso in CMsongpoetNo ratings yet

- Greek AlphabetDocument16 pagesGreek AlphabetEthiopia HagereNo ratings yet

- Madni Aqa Ka Rushan Faslay by Imam Jalaal Ud Deen Sayooti (R.A)Document110 pagesMadni Aqa Ka Rushan Faslay by Imam Jalaal Ud Deen Sayooti (R.A)Mateen Ahmed RazaNo ratings yet

- An Architecture For The Runic AlphabetsDocument20 pagesAn Architecture For The Runic AlphabetsRichter, JoannesNo ratings yet

- ShortcutsDocument11 pagesShortcutsMatthew StewartNo ratings yet