Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Chekists in Cassocks-The Orthodox Church & The KGB

Uploaded by

Καταρα του ΧαμOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Chekists in Cassocks-The Orthodox Church & The KGB

Uploaded by

Καταρα του ΧαμCopyright:

Available Formats

Chekists in Cassocks: The Orthodox Church and the KGB

KEITH ARMES*

Of all Russian central institutions, the Russian Orthodox Church and the security bureaucracies alone have survived the collapse of the Communist system. In fact, the last six years have seen an impressive revival of religious life throughout the former Soviet Union. Despite this rebirth, the institution of the church, in particular the Moscow Patriarchate, is having difficulty maintaining its identity and credibility after seventy years of faithful service to the Communist Party. Today, the church faces not only the ugly confirmation of the KGB's active role in its day to day affairs and the personal corruption of some of its highest leaders, but also the establishment of an independent Ukrainian church, a bid for the loyalty of its flock from the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad, an invasion of well-financed Protestant evangelists, and a backlash against its ecumenical policies. Thus, on the one hand, the Russian Orthodox Church can celebrate its recent advances: 6,000 reopened churches since 1987; the appointment of chaplains to Cossack units which may lead to their integration into the armed services; and the political ascension of former church dissidents like Father Gleb Yakunin to legitimate roles in government. On the other hand, the highest ranks of the institution remain shadowed and marked by a history of allegiance to temporal politics. The opening of some KGB archives since August 1991 has made available for the first time clear evidence of the subordination of the Orthodox hierarchy to the Soviet government. An investigative journalist, Alexander Nezhny, was able to establish the close relationship between a number of bishops and the organs, and to determine the identities of the bishops involved on the basis of the chronology of missions abroad undertaken by hierarchs at the behest of the KGB and references to the agent names (klichki) by which they were known. In particular, the KGB affiliation of three prominent hierarchs is now established: the recently deposed Metropolitan Philaret of Kiev (code name Antonov), Metropolitan Yuvenali of Krutisk and Kolomna, who was head of the foreign relations department of the patriarchate (code name Adamant), and Metropolitan Pitirim of Volokolamsk and Yurev, head of the publishing department of the patriarchate (code name Abbat). It is also established that the present patriarch, Aleksi II, served the KGB under the poetic name

*

Keith Armes is associate director of the Institute for the Study of Conflict, Ideology and Policy, Boston University.

THE ORTHODOX CHURCH AND THE KGB

73

Blackbird (Drozdov). Investigations carried out in the KGB archives by Lev Ponomarev, chairman of the short-lived Russian Supreme Soviet Commission to Investigate the Causes and Circumstances of the Putsch, and Father Gleb Yakunin, who served as a member of that commission, make it clear that the chain of command for controlling the church ran directly from the Politburo through the CPSU Central Committee Department of Agitation and Propaganda, to the USSR Council of Ministers' Council on Religious Affairs, and finally to the KGB, which had a special subdivision (Fourth Department of the Fifth Administration) for religion. There is abundant evidence of the KGB's control of the church's activities abroad and its success in ensuring that the World Council of Churches (WCC) consistently adopted positions [The Ponomarev Commission advantageous to the Soviet leadership. discovered] that the chain of Thus in 1980, a KGB report signed command for controlling the by the head of the Fourth Department church ran directly from the states, . . . the secretary general of Politburo through the CPSU the World Council of Churches, Central Committee Department Philip Potter, has been in Moscow as of Agitation and Propaganda, to a guest of the Moscow Patriarchate. the . . . Council on Religious A favorable influence was exercised on him by agents `Svyatoslav,' Affairs, and finally to the KGB. . `Adamant,' `Mikhailov,' and . `Ostrovsky.' Information of operational interest was obtained on the activities of the WCC. In 1983, the KGB dispatched 47 [sic] agents to attend the WCC General Assembly in Vancouver. In the following year, KGB reports make it clear that the Uruguayan Emilio Castro was elected WCC general secretary with the assistance of its agents attending the session of the selection committee. At a major Orthodox Church conference in Moscow in 1988, the situation among the participants was checked by clandestine means, and a positive communiqu was adopted in which a principled appraisal was adopted by the episcopate of the Russian Orthodox Church of the activities of religious extremists [dissidents] in our country. The KGB reported on its work at the July 1989 WCC meeting in Moscow, As a result of measures carried out, eight public statements and three official letters were adopted which were in accordance with the political line of socialist countries . . . Thanks to our agents a positive effect was exercised on the foreigners, and additional ideological and personality data were obtained, [as well as] information on their political views and the positions they occupied in their own countries. Numerous interviews took place that were favorable to us. A facsimile document dated November 1987, and published by the former

74

DEMOKRATIZATSIYA

KGB officer Stanislav Levchenko, confirmed in striking fashion the extent of Party control over the Orthodox Church's affairs. According to this paper, the approval of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the KGB, the Council on Religious Affairs (in the person of its chairman, Konstantin Kharchev), and the CPSU Central Committee's Propaganda Department, was required for the church to send priests to serve Orthodox parishes in Brazil and Uruguay.1 There is evidence that KGB officers were sent to study at seminaries abroad in order to become priests and serve in the Soviet Union.2 The KGB paid particular attention to relations with the Vatican. A 1989 report by Col. V. Timoshevsky, head of the KGB's Fourth Department, states, The most important journeys were those by the agents `Antonov,' `Ostrovsky,' and `Adamant' to Italy for negotiations with the Pope on questions of future relations between the Vatican and the Russian Orthodox Church, in particular the problems of the Uniates.3 The patriarchate's External Affairs Department consisted almost entirely of KGB agents. The department's main ideologist, Buevsky, a KGB officer now venerable leastwise in years, has been responsible for writing the patriarch's public statements and encomia on successive national leaders since 1946.4 A prominent priest, Father Georgi Edelshtein, has stated that one-half of the clergy were overt or covert KGB employees through the end of the . . . none of the prominent bishops attending a conference in Gorbachev era. He has confirmed that the hierarchy took large bribes Moscow on 19 August 1991 from priests seeking transfers to rich condemned the putsch. Not one parishes and from candidates for came to the White House to bless bishoprics. Father Edelshtein its defenders. . . comments, Do you know where our present-day church ends and the KGB begins? The only difference was that some wore hoods and some had shoulder boards.5 Until very recently, the conduct of some members of the episcopate showed no trace of aggiornamento. In 1990, a group of students asked the Bishop of Chelyabinsk for help in organizing an Orthodox youth group to look after new converts. This prelate requested a list of the organizers, which he then sent to the local KGB. The KGB, however, wrote back to the bishop informing him that their duties no longer included such internal matters, and passed on copies of the correspondence to the city soviet for publication.6 Father Gleb Yakunin has stated that within the top church hierarchy, nine out of ten were KGB agents.7 Significantly, none of the prominent bishops attending a conference in Moscow on 19 August 1991, condemned the putsch. Not one came to the White House to bless its defenders who faced death protecting the legal government of Russia from the overthrow attempt by military forces.8 It is a reasonable assumption that many hierarchs were recruited by the KGB at the seminaryor even initially sent to the seminary by a patron with blue

THE ORTHODOX CHURCH AND THE KGB

75

epaulettesand marked out from the beginning for a distinguished clerical career. For these men, the practice of religion meant the search for and attainment of warm places and high preferment. So far, however, documentary evidence for such recruiting is lacking. In January 1992, further access to the archives was denied to Supreme Soviet investigative commissions with the approval of the chairman of the Supreme Soviet, Ruslan Khasbulatov, after joint presentations had been made to him by the chairman of the Russian External Intelligence Service, Yevgeny Primakov, and Patriarch Aleksi.9 Particularly damaging to the credibility and moral stature of the Orthodox hierarchy is the degree to which the current patriarch is morally compromised by a career of subservience to the Politburo. According to the KGB archives, in February 1988, the KGB chairman rewarded Aleksi II with a Certificate of Honor for successful performance.10 In 1965, as Archbishop of Tallinn, Aleksi demanded that Archbishop Hermogen of Kaluga, who at the time was undoubtedly the most courageous of all the bishops of the Moscow Patriarchate, go into forced retirement for signing a protest against the complicity of the Synod in the Soviet government's campaign of church closures.11 The patriarch's behavior during the August coup was a classic case of temporization. After initially failing to condemn the putsch, the following day he released a carefully measured statement: [The] situation is troubling the conscience of millions of our compatriots who are beginning to question the lawfulness of the newly formed State Emergency Committee. . .We are hoping that the USSR Supreme Soviet will give a principled assessment and take resolute measures to stabilize the situation in the country. Aleksi was well aware that there was no prospect of the Supreme Soviet's meeting in the immediate future, nor a possibility for taking resolute measures. It was not until the afternoon of August 21 that the patriarch, sensing which way the wind was blowing, agreed to sign an appeal that condemned the putsch leaders' shedding of innocent blood and rejected Communist ideology.12 Despite repeated calls upon him for a public and formal expression of contrition for his servility to the Communist leadership and lies on its behalf, Aleksi has always declined to make a public declaration of repentance. For those who still hoped for change at the highest level of the hierarchy, a recent episode proved especially discouraging. There is indisputable evidence that in recent months Patriarch Aleksi lied in denying charges that, in November 1991, he had approached a U.S. undersecretary of state to put pressure on Voice of America to change its programming about the Russian Orthodox Church.13 The patriarch felt impelled to make this extraordinary dmarche by his concern about the bias against the patriarchate displayed in programs produced by a prominent priest of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad, Father Viktor Potapov.

76

DEMOKRATIZATSIYA

The Church in Ukraine The career of Metropolitan Philaret of Kiev and Galicia has also gravely damaged the moral stature of the church. Philaret's rise was extraordinarily rapid, and he enjoyed successive preferment to Bishop of Vienna and Austria, and then rector of the Moscow Spiritual Academy. No less an authority than Konstantin Kharchev, former chairman of the Council on Religious Affairs, who was removed in 1989 for excessive independence, has confirmed Philaret's KGB connection. Otherwise, he could never have pushed his way into a leading position in the Russian Orthodox Church. As the elected Locum Tenens to the Patriarchal Throne, he had appeared destined to be the next patriarch. However, it was Aleksi who was Under the ancien rgime in elevated to the position in 1990. Ukraine . . . [Metropolitan] Kharchev finds the metropolitan's Philaret vilified Rukh leaders as performance to have been exemplary `bandits' and `provocateurs,' and in terms of satisfying the campaigned in elections for the requirements of the Soviet governCPSU. ment. From the viewpoint of a Party official . . . Philaret was the most literate of all the members of the Holy Synod. All the tasks we assigned to him in the area of foreign relations he carried out brilliantly . . . He was a superb executor . . . Naturally it all boiled down to defending and advocating the party's position. Well, you know: `There's no pressure on the church, the church in our country runs its affairs freely,' in other words, pardon the expression, the raving of a gray mare.14 Were it not for the baneful consequences for the church, Philaret would appear a picturesque personage, a prelate who would not have been out of place on the banks of the Tiber when slashed doublets and codpieces were in vogue. He ran his exarchy with a hand of iron, exiling and banning priests who dared criticize him. The prince of the church lives openly with a woman, known to the clerical fraternity as the First Lady of the Exarchyor less reverentially as Herodiadaby whom, despite monastic vows of chastity, he has had three children. His consort openly attends church ceremonies in his company and is widely believed to be responsible for making church appointments in Ukraine, including episcopal nominations.15 Under the ancien rgime in Ukraine, when nationalism was persecuted, Philaret vilified Rukh leaders as bandits and provocateurs, and campaigned in elections for the CPSU. He prohibited his clergy from preaching in the Ukrainian language. As the strength of the Ukrainian independence movement grew, however, Philaret perceived where the future lay and hastened to serve the

THE ORTHODOX CHURCH AND THE KGB

77

new dispensation, attacking the Great Russian chauvinism of the Moscow Patriarchate. At the same time, Philaret conducted a violent campaign against a major rival, the Ukrainian Autocephalic Church, which had been established in 1989. This church is currently headed by the ailing 93-year-old Patriarch Mstyslav, who remains a resident of the United States. Although its canonicity is not recognized by other Orthodox, the church has had considerable success in winning parishes from the Ukrainian Orthodox Church under Moscow Patriarchal jurisdiction, as well as in securing financial support from abroad for its activity. As Ukraine achieved political independence from Moscow, Philaret rapidly transformed himself from committed supporter of Soviet internationalism and Muscovite rule to a fervent Ukrainian nationalist. In 1985, Philaret, still a faithful ally of Politburo member and longtime Party ruler of Ukraine, Vladimir Shcherbitsky, rejected an offer of autonomy. However, to enhance his position with Ukrainian nationalist political forces, in the autumn of 1990, he obtained autonomous status for the Ukrainian Church from Moscow, and he naturally continued as its head. President Leonid Kravchuk fully realized Philaret's value to his regime, and proposed to Patriarch Aleksi II that the new Ukrainian Orthodox Church be made autocephalous, and that Philaret be elevated to head of the new church. Despite Philaret's political conversion and political allies at the highest level, there continued to be enormous pressure in the press and within his own church to resign, including a public appeal by eight Ukrainian bishops that he lay down his office. Patriarch Aleksi continued to be unwilling to take any action against Philaret, although his scandalous administration of his exarchy and personal behavior damaged resurgent church life in Ukraine and bought the entire hierarchy into disrepute. Finally in April 1992, Philaret stated his intention to step down, and the following month he formally committed himself to resign at an Episcopal Council in Moscow. Immediately on his return to Kiev, however, he withdrew his promise, stating that he had been subjected to moral torture of the cruelest kind. Following this, a Synod of the Church in Moscow revoked Philaret's ecclesiastical authority and threatened him with trial by an episcopal court. Philaret still refused to step down, and in June another Episcopal Council removed him as head of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church and revoked his ordination. Undaunted, Philaret responded by calling on the Patriarch of Constantinople to condemn the action and declare the Ukrainian Church to be completely independent of Moscow. But a more stunning display of political virtuosity by Philaret was yet to come. At a joint press conference on 25 June 1992, with Metropolitan Antoni of the Ukrainian Autocephalic Church, Philaret announced that his church and the Ukrainian Autocephalic Church would form a United Kievan Patriarchate.

78

DEMOKRATIZATSIYA

Patriarch Mstyslav, still absent in the United States, was to become head of the United Patriarchate, while Metropolitan Philaret would occupy the Patriarchal Throne in Kiev as his Locum Tenens. To the amazement of the Orthodox world, Philaret and the Autocephalic Church succeeded in overcoming their violent hostility in order to combine forces against the Moscow Patriarchate. Philaret's spectacular switch of allegiance allowed him to seize the practical authority of the Ukrainian nationalist church on Ukrainian soil after having broken all his bridges with Moscow. Philaret has thus positioned himself to serve the regime of President Kravchuk by continuing the campaign for Ukrainian church independence from the pretensions of the Moscow Patriarchate. In addition, now that the anti-Moscow church forces in Ukraine are united, it is far more likely that the Ecumenical Patriarch in Constantinople will ultimately consent to grant canonical status to the restructured patriarchate in Kiev, which now represents itself to be the sole Ukrainian national church. In turn, it can be expected that the possession of canonicity would induce large numbers of priests who, due to their detestation of Philaret, had previously hesitated to abandon the Moscow Patriarchate to join the new native Ukrainian jurisdiction.16 The extraordinary difficulty the Moscow Patriarchate experienced in removing a metropolitan who had brought profound scandal and discredit on the church typifies the reluctance of the episcopate to deal with the destructive heritage of the Soviet era. The conclusion imposes itself that Philaret knows much that his church colleagues are most reluctant to see revealed. As long as the members of the present Moscow Patriarchate conceal their past conduct, they will remain vulnerable to pressure from those who would prefer not to lance the ulcers on the body of the church. Whereas the Moscow hierarchy, headed by Aleksi, continues to jeopardize the moral repute of the church, there can be no question of the personal dedication to their flocks of the great majority of the ordinary clergy. Parish priests are frequently overwhelmed by the calls upon them by newly active believers to provide instruction and to celebrate the rituals of the church. The already existing grave shortage of priests has been aggravated by the fact that historically the majority of seminarians have come from Ukraine. With the growth of Ukrainian nationalist sentiment, most of the students have left the Moscow Patriarchate to serve churches in their homeland. The Russian Church Abroad Aleksi's sensitivity to criticism of the church by a prominent priest of the Russian Church Abroad reflects the influence that the Church Abroad, although based in the United States, is gaining in Russia. This church (otherwise known as the Synod) was founded by bishops who went into exile rather than subject themselves to Bolshevik rule. Alone among Russian Orthodox jurisdictions, the Church Abroad has always categorically rejected any accommodation with the

THE ORTHODOX CHURCH AND THE KGB

79

Moscow Patriarchate. The church's ability to attract prominent converts among intellectuals in the United States has contributed to its influence. Needless to say, both the Church Abroad and the Moscow Patriarchate regard each other as uncanonical. The Church Abroad maintains, in particular, that the Moscow Patriarchate's lack of canonicity proceeds from the election of a patriarch under Stalin in 1943, and the impermissible intervention of the temporal power in the supreme church appointment. Although many prominent Synodal clerics and laymen of the Church Abroad consider the patriarchate and thus its sacraments to be devoid of grace (bezblagodatny), it was not until very recently that statements were made by Metropolitan Vitali suggesting that this was the official view of the Church Abroad. Such a position puts the church at risk of being considered sectarian and possibly heretical by many prominent Orthodox.17 In March 1990, the Church Abroad proclaimed the intention to extend its jurisdiction to Russia and begin to ordain priests in Russia. It would also accept priests already serving who were ready to abandon the Moscow Patriarchate and join its ranks. Thus within Russia there now exists what is termed the Free Church or the True Church, owing allegiance to the hierarchy of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad. The extent to which the patriarchate is seen as morally Alone among Russian compromised and unwilling to make Orthodox jurisdictions, the amends for the unprincipled policies Church Abroad has always of the past makes many priests and categorically rejected any faithful receptive to the arguments accommodation with the and witness of the Church Abroad. Moscow Patriarchate. Seminarians regularly refer to the Holy Synod as the Metropolitburo. Moreover, the new concern for Russia's pre-Bolshevik heritage contributes to a readiness to see the Church Abroad as embodying historical religious values. Here an important element is the devotion of the Church Abroad to the Russian monarchy and its canonization of the last tsar, murdered by the Bolsheviks. Also contributing to the sympathy enjoyed by the Free Church among many Russian faithful is its implacable opposition to ecumenism, especially in view of the widespread resentment of the proselytization which is being conducted in Russia by missionaries belonging to Western Protestant churches and sects that combine their substantial financial resources with ignorance of Russian life and culture.18 Many Russian clerics reject religious pluralism and strongly condemn the activities in Russia of all non-Orthodox denominations. A Moscow priest is quoted as saying in late 1991, Moscow isn't a Babylon for second cults, for Protestant congregations who resemble wild wolves rushing in here or Catholics like thieves using their billions to try to occupy new territory.19 In addition, many Russian priests are highly unreceptive to theological modernism and

80

DEMOKRATIZATSIYA

libertarian trends in Western churches, not to speak of liberation theology. Such tendencies are associated with the World Council of Churches, which is despised for defending the antireligious policy of the Communist government at the instigation of the KGB agents in cassocks, while it did nothing to support the priests and faithful who rotted in the gulag for their beliefs. That the Kremlin managed to handcuff the largest predominantly Protestant organization in the world is one of its greatest foreign policy achievements since World War II.20 The intransigently anti-ecumenical position of the Church Abroad in contrast to the patriarchate's cooperation with alien Protestant organizations at the behest of the Soviet government permits the Free Church to be seen as a bulwark against Western encroachments on the Orthodox faith. Needless to say, the Moscow Patriarchate is fiercely opposed to the policy of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad of expanding its jurisdiction into Russia. There have been many instances where, at the instigation of the patriarchate, the civil authorities have refused to register Free Orthodox parishes (in violation of the law) or have turned newly opened churches over to the patriarchate at the request of artificially constituted groups of lay persons. It has been reported that KGB agents and police have used violence against believers who wanted to have a priest of the Free Orthodox Church. In one much-publicized episode, a priest in St. Petersburg was persecuted with the cooperation of the city authorities for establishing a parish of the Free Orthodox Church in an abandoned monastery church, while the metropolitan of St. Petersburg threatened his parishioners with excommunication.21 The creation of parishes in Russia by the Russian Orthodox Church . . . the World Council of Abroad is also opposed by a number Churches . . . is despised for of prominent clerics and laymen defending the antireligious belonging to Orthodox jurisdictions policy of the Communist government at the instigation of the outside Russia, who are willing to KGB agents in cassocks, while it accept the authority of the Moscow Patriarchate in spite of its did nothing to support the transgressions. Some opponents priests and faithful who rotted object strongly to what they view as in the gulag for their beliefs. the Russian church's schismatic activity, and reject any implication that the Moscow Patriarchal Church lacks grace. Prominent Orthodox lay author Nikita Struve writes, To consider that the Russian Orthodox Church is devoid of grace is blasphemy against the Holy Ghost. . .22 The Russian Orthodox Church Abroad, on the other hand, takes the view that its parishes in Russia have finally returned to the true Orthodox Church. According to the Church Abroad, the Moscow Patriarchal Church must formally renounce Patriarch Sergi's 1927 declaration of support for the Soviet government

THE ORTHODOX CHURCH AND THE KGB

81

in order to regain canonical standing. In addition, it must reject the heresy of ecumenism and glorify the new martyrs of the faith, including Tsar Nicholas II. The Church Abroad refuses to recognize as a renunciation of detestable Sergianism Aleksi's statements that the church's past policies should now be regarded as belonging to history, and that such acts were taken under pressure in order to safeguard the continued existence of the church. To this Bishop Georgi Grabbe of the Church Abroad responds, The Patriarch is right when he says that the Declaration of 1927 is history. But what is there not in history? In it there are the exploits of the martyrs and the confessors, but in it there is also the treachery of Judas.23 The sensitivity displayed by the Moscow Patriarchate, as well as by nonRussian Orthodox jurisdictions, at the activity of the Russian Church [The Church Abroad] will retain Abroad on Russian soil reveals their its appeal to independentalarm at the inroads that the Church minded and dedicated priests as Abroad is making among the faithful long as the Moscow Patriarchate in Russia. If some priests go over to a is seen by many as irrevocably church that is not guilty of complicity in the crimes of Stalin and his morally comprised and more successors, mainly to escape the committed to material wellauthority of a bishop with whom they being and the elimination of are at odds, it is not surprising that in dissent than the spiritual welfare other cases parish priests are unwill- of the faithful. ing to submit to the sway of hierarchs who continue to enjoy opulent office after a career of KGB service, and moreover propagate ecumenism. These defections occur even though the disincentives against deserting the Moscow Patriarchate are great. Not only are such priests frequently subjected to persecution by the local authorities, but these family men who go over to the jurisdiction of the Free Church suffer greatly materially and lose the pension rights they would have otherwise enjoyed as members of the official church. Despite the pressures on priests to conform to the Moscow line, the number of parishes in Russia under the jurisdiction of the Church Abroad has been steadily growing during the last few years. The Church Abroad now claims fifty-four parishes in Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine, including six in Moscow, one in St. Petersburg, and three in Nizhny Novgorod.24 In addition, most priests of the Catacomb Church who had gone underground with their flocks rather than subject themselves to the rule of the Moscow Patriarchate, have joined the Free Church. This church will retain its appeal to independent-minded and dedicated priests as long as the Moscow Patriarchate is seen by many as irrevocably morally comprised and more committed to material well-being and the elimination of dissent than the spiritual welfare of the faithful.

82

DEMOKRATIZATSIYA

Not surprisingly, the Free Church, guiltless of complicity in Communist crimes against Russia and devoted to the monarchy, readily attracts patriotic elements. Right-wing political groups endeavor to enlist the support of the church's adherents. As the political struggle intensifies, it will be difficult for the church to avoid association with Russian nationalism. Will a portion of the moral intransigence that the church has displayed in the past enable the Free Church to assert its refusal of co-optation by political factions? Conclusion Many senior clerics and lay people in Russia doubt that the Muscovite patriarchal hierarchy is capable of radical reform and spiritual regeneration. The policies of the patriarchate are likely to remain in history as an extreme example of zealous cooperation of an episcopate with an ideologically alien temporal power. In the past, prelates have not always bent the spine before a revolutionary or dictatorial regime. It will be remembered that only seven French bishops took the oath to the Civil Constitution of the Clergy in 1791, and that ten years later almost all the non-juror bishops preferred poverty in exile to subscription to the Concordat of 27 Messidor. There are signs that in order to assure its future position, the Moscow hierarchy is now seeking political allies on the right to replace its former patrons. It is noteworthy that in his official travels to places of pilgrimage, Aleksi permits himself to be guarded by blackshirted troopers from paramilitary groups of the Russian nationalist extreme Right. Pending a decisive turn of the tide, however, the hierarchy displays an astounding determination to demonstrate its subservience to political authorityeven if that loyalty is to the collapsed Communist regime. Metropolitan Yuvenali, chairman of the Synodal Commission on Canonization, holds that martyrs of the church who suffered under Bolshevik rule cannot be canonized until the church receives official certification from the state that they were not state criminals and that they have been politically rehabilitated.25 The crisis of trust in the church greatly reduces it stature and diminishes its capacity to make fitting contribution to building a new Russia. Nevertheless, the hierarchy continues to be resolute in resisting calls for public repentance for past acts and for the establishment of church courts to remove the most compromised members of the senior clergy. Many prominent lay- men also hold that only new institutions, such as a radically reformed governing body of the church with greatly expanded membership and the election of priests and bishops at assemblies in which lay persons participate, can restore confidence in the Russian Orthodox Church under the Moscow Patriarchate.26 If far-reaching reform measures are not adopted, the influence of less compromised and more vigorous Russian jurisdictions will continue to growand the missionary

THE ORTHODOX CHURCH AND THE KGB

83

activity of Protestant as well as non-Christian religious groups will find success with the Russian flock. In the meantime, one must agree with the view that the Moscow Patriarchate is an island of Stalino-Brezhnevite reality.27 Notes

1 The quotations for KGB reports as well as the facsimile report referred to will be found in Stanislav Levchenko, Pogony pod ryasami (Shoulderboards Beneath Cassocks), Novoe Russkoe Slovo, 16 April 1992, p. 16. For evidence of WCC General Secretary Philip Potter's unwillingness to condemn religious prosecution in the Soviet Union, see Kent R. Hill, The Soviet Union on the Brink: An Inside Look at Christianity and Glasnost (Portland, Oregon: Multnomah, 1991), p.143-144. 2 Professor Yuri Rozenbaum, quoted in Kamo gryadeshi, svataya tserkov? Ogonek, No. 18-19 (May) 1992, p. 13. 3 Alexander Nezhny, Tretye imya, Ogonek, No. 4 (January) 1992, p. 3. 4 Information provided by a former employee of the department, Deacon Andrei Ribin. See Orthodox Life, No. 3 (1992), p. 33. 5 Father Georgi Edelshtein, interview, Argumenty i Fakty, No. 36 (September) 1991, p. 7. 6 Father Anthony Ugolnik, Franklin and Marshall College, The Orthodox Church and Contemporary Politics in the USSR, unpublished paper, 1991, p. 12. 7 Press conference of the Russian Federation Supreme Soviet Com mission to Investigate the Causes and Circumstances of the Putsch (the Ponomarev Commission), 25 December 1991, Foreign Broadcast Information Service [FBIS]-SOV-91-248, 26 December 1991, p. 42. 8 Alexander Nezhny, Nad bezdnoi, Ogonek, No. 37 (September) 1991, p. 7. 9 Interviews of Father Gleb Yakunin and Father Vyacheslav Polosin by Kent R. Hill, in Hill, The Orthodox Church and a Pluralistic Society, p. 23, Russian PluralismNow Irreversible?, ed. Uri Ra'anan et al. (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1992) p. 181-82 . Lev Ponomarev believes that the reason that his Supreme Soviet Com mission was closed down was its members' exposure of church hierarchs as KGB agents. (Kamo gryadeshi, svyataya tserkov? p. 12). 1O Text of document from KGB archive quoted in Kamo gryadeshi, svyataya tserkov?, p. 13. 11 Jean Besse, Quelle Voie Pour L'Eglise Russe, Le Messager Orthodoxe, No. 115 (1990), p. 17. 12 Three Days in August: August 19-21, 1991. Chronicle of a Coup d'tat (Moscow: Postfactum & Interlegal, 1991), p. 35; Savik Shuster, The Role of Radio Liberty During the Putsch, The Impact of Foreign Broadcasts in Russian PluralismNow Irreversible?, p. 159. 13 See Alexander Webster, The Price of Prophesy: Orthodox Churches on Peace, Freedom and Security (Washington, D.C.: Ethics and Public Policy Center, 1992), p. 119-120. 14 Interview of Kharchev by Alexander Nezhny quoted in Nezhny, Ego blazhenstvo bez mitry i zhezla, Ogonek, No. 48 (November) 1991, p. 9. 15 Alexander Nezhny, Ego blazhenstvo bez mitry i zhezla, Ogonek, No. 49 (December) 1991, p. 21-22. 16 See Ugolnik, p. 54-55, 58-59. 17 Telephone interview with Father Alexander F.C. Webster, Ethics and Public Policy Center, Washington, D.C., 22 June 1992. 18 See Mark Elliott and Robert Richardson, Growing Protestant Diversity in the Former Soviet Union, in Russian PluralismNow Irreversible? p. 189-203, and Western Mission Perestroika in Central and Eastern Europe, Evangelical Missions Quarterly, January 1992, p. 8-10. 19 Elisabeth Rubinfien, Orthodox Revival, The Wall Street Journal, 20 December 1991,

84

DEMOKRATIZATSIYA

quoted by Kent R. Hill, The Orthodox Church and a Pluralistic Society, Russian Pluralism Now Irreversible?, p. 171. 20 Kent R. Hill, The Soviet Union on the Brink, p. 136. See the discussion by Hill of the WCC's policies (p. 135-165), including anecdotal episodes of subservience to Soviet views, written before documentary evidence of KGB involvement with the WCC became available. 21 See Pravoslavnaya Rus, No. 12 (1991) p. 15; No. 16 (1991), p. 11; No. 17 (1991), p. 17. 22 Struve, Ot redaktsii, Vestnik Russkogo Khristianskogo Dvizheniya, No. 159 (1990), p. 4. 23 Grabbe, Dogmatizatsiya Sergianstva, Pravoslavnaya Rus, No. 17, (1991), p. 6. 24 I am grateful to Father Roman Lukianov of Boston for information on the activity in Russia of the Russian Church Abroad. A list of the parishes of the Free Orthodox Church was received from Bishop Hilarion of New York. 25 Kamo gryadeshi, svyataya tserkov? p. 13. 26 See, for example, the program of church reform advocated by D. Pospelovsky, Russkaya pravosavnaya tserkov segodnya i novy patriarkh, Vestnik Russkogo Khristianskogo Dvizheniya, No. 159 (1990), p. 227-228. 27 Father Georgi Edelshtein, quoted in Kamo gryadeshi, svyataya tserkov? p. 13.

You might also like

- Beware The WindigoDocument4 pagesBeware The WindigoΚαταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- Turkey Threatens To Expel 100,000 Armenians Over Genocide' RowDocument2 pagesTurkey Threatens To Expel 100,000 Armenians Over Genocide' RowΚαταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- Cannibals and Clowns of The Anishinabe and Other North American Native GroupsDocument10 pagesCannibals and Clowns of The Anishinabe and Other North American Native GroupsΚαταρα του Χαμ100% (1)

- Armenian Genocide Debate Exposes Rifts at ADLDocument3 pagesArmenian Genocide Debate Exposes Rifts at ADLΚαταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- Vinnytsia-The Katyn of Ukraine (A Report From An Eye Witness)Document9 pagesVinnytsia-The Katyn of Ukraine (A Report From An Eye Witness)Καταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- Evil Spirit Made Man Eat Family, A Look Back at Swift RunnerDocument3 pagesEvil Spirit Made Man Eat Family, A Look Back at Swift RunnerΚαταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- Obama Declines To Call Armenian Deaths in World War I A ''Genocide''Document2 pagesObama Declines To Call Armenian Deaths in World War I A ''Genocide''Καταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- Imagining Orientalism, Ambiguity and InterventionDocument7 pagesImagining Orientalism, Ambiguity and InterventionΚαταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- The Turkish - Israeli Connection and Its Jewish RootsDocument3 pagesThe Turkish - Israeli Connection and Its Jewish RootsΚαταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- The Hidden HolocaustDocument2 pagesThe Hidden HolocaustΚαταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- Turkey Condemns 'Genocide' VoteDocument2 pagesTurkey Condemns 'Genocide' VoteΚαταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- The Racial Makeup of The TurksDocument5 pagesThe Racial Makeup of The TurksΚαταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- Pan TurkismDocument10 pagesPan TurkismΚαταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- Documenting and Debating A Genocide'Document6 pagesDocumenting and Debating A Genocide'Καταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- Statistics of Turkey's DemocideDocument9 pagesStatistics of Turkey's DemocideΚαταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- Grey Wolves Kill A Peaceful Protestor in Cyprus (1996)Document6 pagesGrey Wolves Kill A Peaceful Protestor in Cyprus (1996)Καταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- Ataturk's ReformsDocument13 pagesAtaturk's ReformsΚαταρα του Χαμ80% (5)

- History of The Turkish JewsDocument11 pagesHistory of The Turkish JewsΚαταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- Istanbul-Gateway To A Holy WarDocument4 pagesIstanbul-Gateway To A Holy WarΚαταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- Was Kemel A Freemason?Document5 pagesWas Kemel A Freemason?Καταρα του Χαμ100% (1)

- When Ataturk Recited Shema Yisrael ''It's My Secret Prayer, Too,'' He ConfessedDocument4 pagesWhen Ataturk Recited Shema Yisrael ''It's My Secret Prayer, Too,'' He ConfessedΚαταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- Turkish Gunman Wants To Be Baptised at The VaticanDocument2 pagesTurkish Gunman Wants To Be Baptised at The VaticanΚαταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- Susurluk and The Legacy of Turkey's Dirty WarDocument4 pagesSusurluk and The Legacy of Turkey's Dirty WarΚαταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- Was Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, Founder of Modern Turkey, Crypto-Jewish?Document5 pagesWas Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, Founder of Modern Turkey, Crypto-Jewish?Καταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- Remembering The Maras Massacre in 1978Document3 pagesRemembering The Maras Massacre in 1978Καταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- Scandal Links Turkish Aides To Deaths, Drugs and TerrorDocument4 pagesScandal Links Turkish Aides To Deaths, Drugs and TerrorΚαταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- Turkey's Pivotal Role in The International Drug TradeDocument5 pagesTurkey's Pivotal Role in The International Drug TradeΚαταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- Turk Who Shot Pope John Paul II Seeks Polish CitizenshipDocument3 pagesTurk Who Shot Pope John Paul II Seeks Polish CitizenshipΚαταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- Gray Wolves Spoil Turkey's Publicity Ploy On 'Ararat'Document3 pagesGray Wolves Spoil Turkey's Publicity Ploy On 'Ararat'Καταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- Papal Assassin Warns Pope Benedict His 'Life Is in Danger' If He Visits TurkeyDocument3 pagesPapal Assassin Warns Pope Benedict His 'Life Is in Danger' If He Visits TurkeyΚαταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

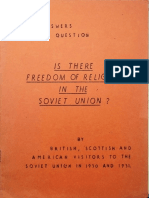

- Is There Freedom Og Religion in USSR 1950-51Document20 pagesIs There Freedom Og Religion in USSR 1950-51Custódio SilvaNo ratings yet

- Bulgarian occupation of Northeastern Greece and breaking up local Church institutionsDocument5 pagesBulgarian occupation of Northeastern Greece and breaking up local Church institutionsiskenderaniNo ratings yet

- 1 Barsoum Ignatius Aphram History of Syriac Diocese Vol 1 EnglishDocument135 pages1 Barsoum Ignatius Aphram History of Syriac Diocese Vol 1 EnglishGerald SackNo ratings yet

- Go C Demetri As 1935 Eng PDFDocument3 pagesGo C Demetri As 1935 Eng PDFPaul.chiritaNo ratings yet

- 1990 Code of Canons of The Eastern ChurchesDocument180 pages1990 Code of Canons of The Eastern ChurchesIvan Zelić100% (1)

- (1909) Costume of Prelates of The Catholic Church: According To Roman EtiquetteDocument346 pages(1909) Costume of Prelates of The Catholic Church: According To Roman EtiquetteHerbert Hillary Booker 2nd100% (1)

- Trinitarian Sep Oct 2013 PDFDocument11 pagesTrinitarian Sep Oct 2013 PDFAlex Sandro Maciel Antunes100% (1)

- Ossae Okr Constitution NewDocument30 pagesOssae Okr Constitution Newchristina johnNo ratings yet

- Civil Case Against Church Maintainable AIR 1995 SC 2001Document68 pagesCivil Case Against Church Maintainable AIR 1995 SC 2001Sridhara babu. N - ಶ್ರೀಧರ ಬಾಬು. ಎನ್No ratings yet

- Ten Reasons Why The Ecumenical Patriarchate Is Not OrthodoxDocument11 pagesTen Reasons Why The Ecumenical Patriarchate Is Not OrthodoxHEILIGE ORTHODOXIE100% (1)

- Dictionary of Canon LawDocument258 pagesDictionary of Canon LawLon Mega100% (3)

- Taxation of Orthodox Church OfficialsDocument16 pagesTaxation of Orthodox Church Officialsomoros2802No ratings yet

- St. Chrysostomos The NewDocument10 pagesSt. Chrysostomos The NewPavel ChiritaNo ratings yet

- 08 Chapter 2Document16 pages08 Chapter 2Sabu Issac Achen Avsm100% (1)

- The Power Struggle Between The Greek Church PDFDocument398 pagesThe Power Struggle Between The Greek Church PDFdtrvicNo ratings yet

- Ottoman Archival Materials on MilletsDocument8 pagesOttoman Archival Materials on MilletsErdem AKINNo ratings yet

- Solia The Herald Jan Feb 2015.compressedDocument24 pagesSolia The Herald Jan Feb 2015.compressedadysssNo ratings yet

- On A Common Accusation Against Metropolitan CyprianDocument1 pageOn A Common Accusation Against Metropolitan CyprianHibernoSlavNo ratings yet

- Quo Vadis Constantinople PatriarchateDocument5 pagesQuo Vadis Constantinople PatriarchateChristosNo ratings yet

- Bulletin of The Syro-Malabar Major Archiepiscopal ChurchDocument71 pagesBulletin of The Syro-Malabar Major Archiepiscopal Churchmet-017-19No ratings yet

- Summer 2003 Orthodox Vision Newsletter, Diocese of The WestDocument20 pagesSummer 2003 Orthodox Vision Newsletter, Diocese of The WestDiocese of the WestNo ratings yet

- Aristotle University Professors Respond To Metropolitan Seraphim of PiraeusDocument3 pagesAristotle University Professors Respond To Metropolitan Seraphim of PiraeusDinu Mihail-LiviuNo ratings yet

- Canon LawDocument258 pagesCanon Lawtam-metni.nasil-yazilir.com83% (6)

- Church and State identity card crisisDocument139 pagesChurch and State identity card crisisJonathan PhotiusNo ratings yet

- Mar Thoma Syrian ChurchDocument46 pagesMar Thoma Syrian Churchmcdermott45No ratings yet

- 02.03. Zhytomyr OblastDocument2 pages02.03. Zhytomyr OblastKateryna KolomiietsNo ratings yet

- FOCUS January 2023Document51 pagesFOCUS January 2023FOCUSNo ratings yet

- Chrysostomos of PhlorinaDocument18 pagesChrysostomos of PhlorinaChristosNo ratings yet

- The Illegitimate "Deposition" of Metropolitan Cyprian and Its Nullification: A Short Response To The Scuttlebutt of Mr. Vladimir MossDocument3 pagesThe Illegitimate "Deposition" of Metropolitan Cyprian and Its Nullification: A Short Response To The Scuttlebutt of Mr. Vladimir MossHibernoSlavNo ratings yet

- Byzantine CatholicsDocument53 pagesByzantine CatholicsPablo CuadraNo ratings yet