Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Article On Research Model

Uploaded by

UZzair BaharudinOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Article On Research Model

Uploaded by

UZzair BaharudinCopyright:

Available Formats

(175(35(1(85,$//($51,1*352&(66(6,1

$&$'(0,&63,12))6

Petra Dickel, Universitv of Kiel, Germanv

Anke Rasmus, Universitv of Kiel, Germanv

Achim Walter, Universitv of Kiel, Germanv

$%675$&7

Academic spin-oIIs are an important means Ior technology transIer Irom public research and strongly

contribute to regional development. However, these companies have to overcome major challenges at start-up.

Academic Iounders oIten lack business know-how and a market-oriented way oI thinking. At the same time

spin-oII technology oIten still is at an early development stage and involves considerable uncertainties.

Accordingly, many spin-oIIs Iollow suboptimal market chances and Iail. SuccessIul entrepreneurs, on the

contrary, learn about markets right Irom the start and incorporate this knowledge in their product development

activities. So Iar, little is known about the nature oI these market-based learning processes in new ventures.

Drawing on a database oI 71 academic spin-oIIs, this study investigates how new ventures learn about

markets at an early stage and how this inIluences market perIormance oI spin-oIIs.

,1752'8&7,21

The role oI universities and public research institutions in transIerring innovative technologies is widely

acknowledged. Technology transIer increasingly becomes important with the change Irom industry to

knowledge based economies with respect to technological progress and economic growth. In the context oI

academic institutions, diIIerent channels oI technology transIer exist, e.g. scientiIic publications, cooperation

and contract research, consulting or licensing. Above all, spin-oIIs are regarded to particularly contribute to

regional economic development (DorIman, 1983; Chrisman et al., 1995; Lockett et al., 2003) and hence have

been subject oI increased interest in the past years. Academic spin-oIIs are companies that are Iounded by

employees oI public research institutions in order to commercialise technology developed within the

institution (SteIIensen et al., 1999).

However, in order to realise positive economic eIIects spin-oIIs must successIully innovate, i.e. transIer

their technology into marketable products. This poses a major challenge Ior a lot oI spin-oIIs (Vohora et al.,

2004). Spin-oII Iounders oIten lack business knowledge and a market-oriented way oI thinking (KloIsten et

al., 1988). At the same time, spin-oII technology oIten is still at an early development stage, i.e. Iar Irom a

possible commercialization and requires Iurther development (Jensen & Thursby, 2001). Thus, it is oIten

ambiguous which product solutions are most appropriate. Furthermore, a single technology can serve diIIerent

markets diIIerently well. This means that academic spin-oIIs can enter many diIIerent markets with their

technology, but only Iew oI those market chances possess high growth potential (Shane, 2000; Ardichvili et

al., 2003). Hence, the decision on a speciIic target market is crucial to spin-oII success. In this context,

traditional market research methods are ill-suited to gain realistic market data and insights due to several

reasons. It is not only the identiIication oI relevant users that already poses a problem at this early stage, also

user needs are mostly latent and thereIore diIIicult to articulate. Besides, concept and prototype evaluation is

hard Ior users in the light oI missing reIerence products and experience (Von Hippel, 1986; Lettl, 2004).

Accordingly, many spin-oIIs Iollow suboptimal market chances without having a clear vision oI relevant

target markets and user requirements and Iail accordingly.

Lynn and Akgn (1998) argue that a learning-based strategy is appropriate in such an environment

characterised by high uncertainties. However, only little is known how learning processes take place in new

ventures. Particularly, there is Iew empirical evidence on how Iounders make sense about the oIten ambiguous

markets and customer needs at an early stage. This study`s objective is to close this gap by investigating

market-based learning processes in academic spin-oIIs as well as iI there are diIIerences in learning between

successIul and unsuccessIul spin-oIIs.

In this article we will Iirst present major theoretical Iindings Irom which main hypotheses are derived.

Then, methodology and results oI an empirical study oI 71 academic spin-oIIs will be presented. We conclude

with managerial implications and Iuture research questions.

Page 1 oI 13

10/10/2011 http://Iusionmx.babson.edu/entrep/Ier/2007FER/cxxip2p.html

THEORY & MODEL

Market-Based Organizational Learning & Entrepreneurship

Organizational learning is 'a process oI improving actions through better knowledge and

understanding (Fiol & Lyles, 1985, p. 803). Learning Iosters innovation, reduces the risk oI knowledge

becoming obsolete and hence contributes to sustaining a company`s dynamic capabilities (Teece et al., 1997).

The concept oI learning is particularly discussed among strategic management and organization research

schools, e.g. in the context oI organizations (Fiol & Lyles, 1985; Huber, 1991; March, 1991; Nonaka, 1994)

and alliances (Lane & Lubatkin, 1998; Larsson et al., 1998; Inkpen, 2000), learning barriers (Kim, 1993;

Szulanski, 1996) or the risk oI outlearning and spill-over eIIects (Hamel et al., 1989; Hamel, 1991). However,

there is neither a common notion nor term oI learning yet. In this paper, learning is conceptualized as a multi-

stage process consisting oI knowledge acquisition and knowledge integration activities (Day, 1994; Zahra et

al., 2000). Knowledge is the result oI learning processes and can be distinguished in explicit and tacit

knowledge. Explicit knowledge can be codiIied in the Iorm oI language, numbers, symbols and Iigures and is

thereIore easy to transIer. Tacit knowledge dependents on context and person, cannot be articulated and is

hence diIIicult to transIer (Polanyi, 1958; Nonaka, 1994).

With respect to market-based learning, there is a wide consensus on the positive relationship between

market and customer understanding and perIormance (e.g. Dougherty, 1990; Kohli & Jaworski, 1990; Narver

& Slater, 1990; Sinkula, 1994; Li & Calantone, 1998). However, existing studies concentrate on established

companies that learn about changes in their business environment and adapt to those changes. The business

environment oI academic spin-oIIs, on the contrary, is not yet deIined and diIIerent in many aspects. First,

spin-oIIs can potentially enter many diIIerent markets with one single technology (Shane, 2000), which places

the emphasis on the deIinition and choice oI relevant target markets rather than the introduction oI

incremental innovations in existing markets. Second, new ventures cannot Iall back on existing knowledge

bases and routines, but rather have to build them up in order to survive and grow. Third, coordination tasks oI

diIIerent organizational Iunctions and departments (e.g. Dougherty, 1990; Narver & Slater, 1990) are less

problematic in new ventures` learning attempts but rather the question how and Irom where relevant market

knowledge can be acquired and how this knowledge can be integrated in new product development. Spin-oII`s

learning requirements thereIore signiIicantly diIIer Irom those oI established companies both in complexity as

well as their direct and long-term consequences on business development.

Although the importance oI learning is widely acknowledged in entrepreneurship research, learning in the

context oI start-ups is still ill-understood (Harrison & Leitch 2005). Most studies Iocus on the individual level

oI the Iounder, i.e. her behavior and cognitive abilities (e.g. Minniti & Bygrave, 2001; Corbett, 2005).

Empirical research on entrepreneurial learning at an organizational level is rare and appears relatively

heterogeneous (Zahra et al., 2006). Studies show that entrepreneurs usually experiment with diIIerent business

models and successively learn about their environment (Nicholls-Nixon et al., 2000; Ravasi & Turati,

2005).Zahra et al. (2000) demonstrate the positive perIormance eIIect oI technological learning gained

through internationalization oI new ventures. Yli-Renko et al. (2001) analyzed knowledge acquisition Irom

key customers; their results illustrate the relevance oI strong personal contacts in entrepreneurial learning

processes. However, organizational learning is oIten conceptualized very generally, e.g. as a Iunction oI

knowledge access structures (Almeida et al., 2003) or the degree oI organizational change (e.g. Nicholls-

Nixon et al., 2001), which hardly contribute to the understanding oI the underlying learning processes. The

case studies oI Xie and White (2004) and Ravasi and Turati (2005) deliver greater in-depth insights by

comparing the learning processes in one start-up each. However, the studies` transIerability is questionable

due to their very speciIic context oI one particular company. Peters and Brush (1996) give diIIerentiated

insights oI new ventures` market inIormation activities but their descriptive study design does not enable to

deduce causal eIIects. Moreover, many studies oI entrepreneurial learning Iocus on technological learning, i.e.

the acquisition and integration oI new technological skills (Zahra et al., 2000; Saemundsson, 2005). Market-

based learning, however, is rarely investigated, which is rather surprising keeping in mind the importance oI

market inIormation especially Ior young companies` survival and growth (Bullinger, 1990; Hemer, 2006).

Vohora et al. (2004) conclude Irom their case studies that spin-oIIs must possess at least some market

understanding to survive. Bond and Houston (2003, p. 132) argue a same and point out that 'market-

technology barriers that we identiIied highlight the importance oI the Iirm`s attention to collecting

inIormation regarding technological possibilities, customer needs, competitors` technology strategy and

market Ieasibility as inputs to making strategic technology decisions.'

This paper`s objective is to build on and extend existing research by analyzing market-based learning

Page 2 oI 13

10/10/2011 http://Iusionmx.babson.edu/entrep/Ier/2007FER/cxxip2p.html

processes in academic spin-oIIs. We particularly investigate how academic spin-oIIs learn about markets at

an early stage and how this inIluences their market perIormance. We diIIerentiate between personal and

codiIied learning as distinct knowledge acquisition strategies and analyze how spin-oIIs integrate market

knowledge in their business activities. We also investigate whether the impact oI these market-based learning

processes change in dynamic environments.

Our study contributes to entrepreneurial learning research by closely analyzing learning processes in

academic spin-oIIs. As well it compares the impact oI diIIerent learning strategies with respect to gaining

market knowledge and shows how dynamic environments eIIect a spin-oII`s learning eIIorts. It Iurther

contributes to organizational learning research by extending market-based learning to the context oI new

ventures.

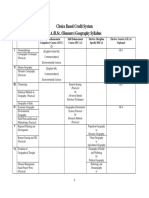

Figure 1 shows the study`s basic research model. According to this, spin-oII`s perIormance is inIluenced by

knowledge acquisition in Iorm oI personal (PL) and codiIied learning (CL) as well as knowledge integration

(KI) activities. A moderating eIIect oI technological dynamism (DYN) is assumed. Market perIormance (MP)

is captured by the spin-oII`s Iirst product success indicating how successIul the company was in transIerring

technology into a marketable product. Constructs and relationships will be discussed in the Iollowing

section.

3HUVRQDODQG&RGLILHG/HDUQLQJ

According to the knowledge based view, knowledge is a company`s most important resource and

perIormance is strongly determined by the ability to apply this knowledge eIIectively (Penrose, 1959; Grant,

1996a). In the case oI academic spin-oIIs, it is necessary to connect their technological know-how with

speciIic market demands (Bond & Houston, 2003). Thus, spin-oIIs must be able to translate their technology

into marketable products by gaining and integrating market knowledge in their product development

activities.

Knowledge can be acquired personally or through codiIied sources, i.e. independent oI other persons (DaIt

& Weick, 1984). Personal learning (PL) reIers to the acquisition oI inIormation and skills that are closely

connected to other persons and hence necessitates close personal cooperation (Peters & Brush, 1996; Hansen

et al., 1999). Both potential users (Von Hippel, 1986), suppliers and competitors (Baum et al., 2000; Vohora

et al., 2004) as well as independent industry experts (Vohora et al., 2004) can be appropriate sources Ior

market inIormation. In the context oI academic spin-oIIs PL plays a pivotal role since relevant market

knowledge usually is not publicly available and concentrated on only a Iew people (Zucker et al., 2002).

Moreover, user needs are mostly latent and thereIore oIten cannot be articulated (Von Hippel, 1986). This

highly tacit knowledge can only be transIerred via personal interaction with potential users and market

experts, in order to make use oI it in spin-oIIs' product development activities (Nonaka, 1994; Lane &

Lubatkin, 1998). Thus, a personal based knowledge acquisition is vital Ior academic spin-oIIs in order to

access the mainly tacit knowledge about markets and user needs. We thereIore assume a positive relationship

between PL and market perIormance.

H

1

. The extent of personal learning positivelv influences a spin-offs market performance. The higher the

extent of knowledge acquisition through personal sources during product development the higher a spin-

offs market performance.

CodiIied learning (CL) reIers to inIormation acquisition independent oI other people through codiIied

sources (Peters & Brush, 1996; Hansen et al., 1999). This explicit knowledge is tradable, e.g. in Iorm oI

traditional market research data and research publications, or is publicly accessible, e.g. in Iorm oI market

data published in internet and print media. Due to its higher transIerability CL involves less time and eIIort in

accessing knowledge than PL. However, the value oI codiIied inIormation acquired is lower since this

inIormation is potentially available to any other party, such as competitors, too. As well it only allows gaining

superIicial general insights (Lane & Lubatkin, 1998). However, we believe that CL complements PL through

the acquisition oI basic know-how, such as legal requirements and general market trends. Thus, we also

expect positive eIIect oI codiIied learning on market perIormance.

H

2

. The extent of codified learning positivelv influences a spin-offs market performance. The higher the

extent of knowledge acquisition through codified sources during product development the higher a spin-

offs market performance.

Page 3 oI 13

10/10/2011 http://Iusionmx.babson.edu/entrep/Ier/2007FER/cxxip2p.html

.QRZOHGJH,QWHJUDWLRQ

In order to become eIIective, knowledge gained needs to be integrated within the organization (Cohen &

Levinthal, 1990; Grant, 1996b). Knowledge acquisition and knowledge integration are thereIore

complementary to each other and deIine an organization`s learning process.

Knowledge integration (KI) is a three-step process that describes how the knowledge gained is captured,

interpreted and used in the company (Zahra et al., 2000). Capture reIers to the documentation and exchange

oI inIormation within the spin-oII in order to make it available to relevant organizational members.

Interpretation is necessary to reIlect and evaluate new inIormation. This takes place by jointly discussing

analyzing successIul and less successIul project activities as well as a rather trial-and-error based inIormation

processing by which a company successively gains clarity on what has been learnt (Von Hippel & Tyre, 1995;

Lynn et al., 1996). Finally new knowledge must be put to use, i.e. applied in new product development.

ThereIore it is mandatory to draw the consequences oI the new market inIormation gained and to integrate this

knowledge into the spin-oII`s business activities. In turn, we expect that KI positively inIluences a spin-oII`s

market perIormance.

H

3

. Knowledge integration describes the capture, interpretation and use of market information acquired.

The extent of knowledge integration positivelv influences a spin-offs market performance. The higher the

extent of knowledge integration during product development the higher a spin-offs market performance.

7HFKQRORJLFDO'\QDPLVP

According to Glazer and Weiss (1993) a market with environmental turbulence is characterized by (1) a

high extent oI inter-period change in the levels or values oI key environmental Iactors and (2) substantial

uncertainty and unpredictability as to the Iuture values oI these variables.

The impact oI dynamic environments is mainly discussed in marketing and strategy research. Jaworski and

Kohli (1993) empirically analyzed the relationship between market orientation and business perIormance and

the impact oI environmental variables that comprise varying degrees oI market turbulence, competitive

intensity and technological turbulence. Their results did not show any signiIicant eIIects oI environmental

Iactors on the market orientation perIormance relationship. Similarly, Calantone et al. (2003) Iound little

support Ior an interaction eIIect between turbulent environments and market orientation on perIormance. The

empirical study oI Han et al. (1998) indicates some diIIerent results. Though they Iound no inIluence oI

market turbulence, they show that technological turbulence moderates the relationship between market

orientation and innovation development. Thus, the impact oI dynamic environments with respect to market

understanding remains ambiguous. However, as these studies Iocus on established companies, the situation

might be quite diIIerent Ior technology-based new ventures, in which the eIIectiveness oI market-based

learning is probably more prone to the degree oI technological dynamism.

Academic spin-oIIs, as most technology based companies, are usually situated in highly dynamic and

volatile environments. This implies that time plays a major role in this context that is characterized by an

acceleration oI market and technological changes and an explosion oI available inIormation (Slater & Narver,

1995). In these environments, spin-oIIs have to cope with an abundance oI new emerging market and

technological data within short time while they develop and commercialize their technology. Bourgeois and

Eisenhardt (1988) describe highly dynamic markets in which changes are so rapid and discontinuous that

inIormation collection at the beginning oI new product development cycle can become obsolete by the time

products are launched. Thus, market inIormation becomes time sensitive in these environments (Glazer &

Weiss, 1993). An immediate and direct access to market knowledge creates a competitive advantage due to

the reduction oI development time oI innovations (Calantone et al., 2003) and the ability to earlier launch and

market new products than competitors. This is crucial in turbulent environments, in which technological liIe

cycles become shorter and technological breakthroughs occur at a more rapid pace. Hence, the capability to

respond rapidly to evolving technical and market inIormation is a critical Iactor to success (Iansiti, 1995). As

competitive advantage oI spin-oIIs strongly depends on their technology and the ability to eIIectively

commercialize it, this study particularly Iocuses on the impact oI technological dynamism (DYN). This is

deIined as a turbulent environment, in which the time intervals between major technological innovations

continuously decrease.

Page 4 oI 13

10/10/2011 http://Iusionmx.babson.edu/entrep/Ier/2007FER/cxxip2p.html

Personal learning is particularly important in dynamic environments, as the highly tacit market knowledge

can only be transIerred in short time via personal interaction with external partners. Close cooperation with

users, suppliers, and market experts hence is necessary to stay abreast oI competitors. TransIerring

inIormation via personal interaction allows accessing up-to-date market inIormation within short time.

Moreover, the direct contact with external partners does not only enable to immediately request and transIer

knowledge, the interacting parties can also instantly Ieedback on the inIormation exchanged and thereby

reduce misunderstandings. Accordingly we assume that an environment characterized by high technological

dynamism reinIorces the relationship between personal learning and spin-oII`s market perIormance.

H

4a

. The extent of technological dvnamism positivelv moderates the effect of personal learning on market

performance of academic spin-offs.

As codiIied learning builds on knowledge acquisition Irom existing and accessible data and publications,

this learning strategy involves the risk that the knowledge sources are less up-to-date than personal sources.

Indeed, codiIied knowledge is characterized by some time lag reIlected in the time between the discovery,

processing, storage and publication oI inIormation and data. Especially market research data, iI available, is

time-delayed as it rather comprises past customer needs and competitor activities than Iuture customer

attitudes and requirements and competitor strategies respectively. Contrary to personal learning, we assume

that a high extent oI technological dynamism weakens the eIIect oI codiIied learning on spin-oII`s market

perIormance.

H

4b

. The extent of technological dvnamism negativelv moderates the effect of codified learning on market

performance of academic spin-offs.

Concerning knowledge integration, spin-oIIs must respond rapidly to new market inIormation. This is

especially the case in highly dynamic environments, in which the ability to react Iaster than competitors is

crucial. II knowledge is not captured, interpreted and used in short time, superior knowledge will become

obsolete and competitive advantage will be lost soon. Accordingly we expect that the relationship between

knowledge integration and market perIormance is reinIorced by technological dynamism.

H

4c

. The extent of technological dvnamism positivelv moderates the effect of knowledge integration on

market performance of academic spin-offs.

0(7+2'2/2*<

To examine the relationship between market learning processes and market perIormance, a study oI 152

spin-oIIs Irom higher education institutions in Germany was conducted. To be included in the sample Iour

criteria had to be met: (1) the spin-oII has been Iounded by employees oI a public research institution, (2) the

spin-oII`s core technology originates Irom this research institution, (3) the company is independent and (4) its

maximum age is 10 years.

Data was collected in Iorm oI standardized questionnaires in personal interviews with spin-oII Iounders. A

multiple key inIormant approach was used as suggested by Kumar et al. (1993) and Ernst (2002) to reduce a

possible inIormant bias. The spin-oII`s Iounder was ask to state on the spin-oII`s characteristics at start-up as

well as perIormance while a second key inIormant who was involved in new product development and launch

(e.g. project manager) was ask in a shorter questionnaire to indicate the knowledge acquisition and integration

activities during that time. The Iinal sample consists oI 116 usable questionnaires oI which 71 were Iully

completed by both key inIormants. These spin-oIIs have an average age oI 5 years, size oI 11,5 employees

and turnover oI 887 Tt in 2005 which is comparable to other studies on academic spin-oIIs (Jones-Evans et

al., 1998; SteIIensen et al., 1999). 37 oI the companies are based on inIormation technology, 21 on

biotechnology, 23 on electronics, photonic and nanotechnology and 19 on other technological Iields.

Scales were either adapted Irom literature or developed speciIically Ior this study. Guidelines set by

Diamantopolous and WinklhoIer (2001) were Iollowed in developing the Iormative scales. Initial item pool

generation is based on in-depth interviews with spin-oII Iounders. Scales were successively pretested and

revised aIter each round. At the end oI the third Iinal round, respondents indicated that the remaining items

were clear, meaningIul and relevant. All items were measured on a seven-point Likert scale.

Personal learning was captured by Iive items on market knowledge acquisition activities by interacting

Page 5 oI 13

10/10/2011 http://Iusionmx.babson.edu/entrep/Ier/2007FER/cxxip2p.html

with diIIerent personal knowledge sources (e.g. customers, competitors, market experts) during new

product development. Similarly, Iive items reIerred to codified learning in terms oI knowledge acquisition

Irom codiIied sources (e.g. databases, magazines, internet). Knowledge integration was measured with eleven

items on the capture, interpretation and use oI market inIormation gained during new product development.

Technological dvnamism was captured by one item that described the extent oI decreasing time intervals

between major technological innovations in the industry.

To evaluate performance, many empirical studies use Iinancial (objective) measures, as e.g. sales, proIit,

cash-Ilow etc. (Geringer & Herbert 1991). Since this data is very oIten diIIicult to collect due to

conIidentiality reasons or non-availability oI data which is particularly the case Ior new ventures

researchers increasingly use perIormance indicators that are based on subjective evaluations oI key

inIormants. A lot oI studies show that these subjective measures highly correlate with objective criteria and

are thereIore an appropriate option Ior perIormance measurement (e.g. Covin & Slevin 1989; Geringer &

Herbert, 1991; Kale et al., 2002). In our study, a subjective perIormance measure was used as dependent

variable. Market performance was measured with seven items that indicate how the spin-oII`s Iirst product

perIormed one year aIter launch in terms oI the achievement oI Iounders` objectives. In order to reduce

inIormant bias, items on learning processes and market perIormance were evaluated by two diIIerent key

inIormants in separate questionnaires as described above.

We controlled Ior prior knowledge in terms oI the Iounders` industry experience in years as well as

existing relationships with customers at start-up. Moreover, spin-oII`s main technological Iield, Iounders'

team size and technological uncertainty at start up were used as controls. Finally we controlled Ior the time

lag between the spin-oII`s start-up and their Iirst product launch.

(03,5,&$/5(68/76

To test the hypotheses a moderated regression analysis was perIormed as suggested by Aiken and West

(1991). According to this, all independent variables are simultaneously considered in a step-wise process in

which Iirst the controls, then the main eIIect variables and Iinally the interaction eIIects are included into the

regression equation. All independent variables were centred prior the computation oI interaction terms.

All measures were analyzed Ior reliability and validity. The correlations (Pearson) oI the main variables

ranged Irom 0.02 to 0.46. Descriptive statistics and correlations oI main variables are shown in table 1.

Moderated regression analysis as shown in table 2 conIirmed the proposed direct positive eIIects oI

personal learning and knowledge integration on perIormance (H

1

and H

3

supported), while there the direct

eIIect oI codiIied learning is not signiIicant (H

2

not supported). However, our results indicate a positive

interaction eIIect oI personal learning and technological dynamism and a negative interaction oI codiIied

learning and technological dynamism on perIormance (H

4a

and H

4b

supported). The eIIect oI knowledge

integration does not change in technologically dynamic environments (H

4c

not supported).

Further tests indicate that multicollinearity is unlikely to pose a problem with variance inIlations Iactors

(VIF) below 1.8 and a maximum condition index (CI) oI 3.9. Multicollinearity possibly exists iI correlations

are above 0.70, VIFs above 10, and CI is higher than 30. Moreover, a multi-trait multi-method (MTMM)

analysis as proposed by Campbell and Fiske (1959) was conducted to control Ior validity oI key inIormants`

statements. MTMM analysis showed that both convergent validity and discriminant validity oI key

inIormants` statements can be conIirmed.

To Iurther analyse results the signiIicant interaction eIIects were graphically plotted as proposed by Aiken

and West (1991). Figure 2 shows the interaction oI personal learning and technological dynamism on

perIormance. Personal learning obviously is oI minor importance when a spin-oII`s environment is less

dynamic but it becomes a crucial Iactor with increasing technological dynamism. On the contrary, codiIied

learning becomes increasingly counterproductive the more a spin-oII`s environment is characterised by high

technological dynamism as shown in Iigure 3.

',6&866,21$1',03/,&$7,216

Summing up, our study shows a positive impact oI personal learning and knowledge integration on spin-

Page 6 oI 13

10/10/2011 http://Iusionmx.babson.edu/entrep/Ier/2007FER/cxxip2p.html

oII`s market perIormance. Results Iurther indicate a positive interaction eIIect oI personal learning and

technological dynamics on perIormance, while codiIied learning has a negative eIIect in technologically

dynamic environments. We conclude that personal learning and knowledge integration are important means

Ior developing marketable products in academic spin-oIIs, while codiIied learning seems to be a less eIIective

or even a counterproductive way to acquire market inIormation at an early stage.

Our results show the importance oI investigating the learning concept in a more diIIerentiated way. A

personal based learning strategy seems to be particularly appropriate in the context oI spin-oIIs; also

knowledge integration is not to be neglected when researching learning processes. Results also indicate that

studies should go beyond the prevailing user perspective. Other market participants such as suppliers,

competitors etc. can also be sources Ior valuable market inIormation Ior new ventures. Finally, learning seems

to be diIIerently important in diIIerent environments, hence environmental Iactors such as e.g. technological

dynamism are also be taken into account when deIining a spin-oII`s appropriate learning strategy.

From a managerial perspective the results underscore the necessity that academic spin-oIIs must learn

about markets already at an early stage in order to realise marketable products and to succeed in the market

place. However, there are diIIerent ways oI learning and their impact diIIers signiIicantly. Concerning

knowledge acquisition a person-based way oI learning is more eIIective than studying inIormation Irom

codiIied sources. Thus, the early integration oI potential customers and suppliers in product development is

mandatory as well as the close interaction with market experts Irom the start. Comprehensive exchange with

diIIerent market partners is crucial to gain a sense Ior markets and close collaboration is necessary to get

valuable market inIormation that otherwise could not be acquired. Market research or any other public

available sources are less eIIective devices to learn about markets at an early stage. This is particularly the

case in technologically dynamic environments in which current publicized data is not up-to-date any more

within a short period oI time. Moreover, comprehensive knowledge integration is a precondition to realize

perIormance eIIects. For this purpose academic Iounders should establish processes that Iacilitate knowledge

Ilows within the organization and set up structures that Ioster open communication and constructive dialogue

between organizational members in order to Iully tap the potential oI what has been learnt.

Although this study provides some interesting results, some limitations are to be mentioned. Our study

used a subjective perIormance measurement, which might give rise to biased responses. As our data builds on

two key inIormants we managed to minimize the risk oI an inIormant bias, at least to some extent, which is

also conIirmed by the MTMM analysis that indicates validity oI results. Further, our data derives Irom a

cross-sectional study. As learning is inherently dynamic in nature, e.g. relevant market knowledge may

change over time according to current needs and requirements, Iuture research should investigate the

development oI learning processes in spin-oIIs and their perIormance impact in a longitudal study. Finally, the

role oI Iurther context Iactors on the eIIectiveness oI entrepreneurial learning would be a promising Iield oI

research. Future studies should thereIore investigate the inIluence oI spin-oIIs` diIIerent start-up

conIigurations in terms oI their resources and entrepreneurial culture to complete our understanding oI

learning processes in academic spin-oIIs.

&217$&7 Petra Dickel; dickelbwl.uni-kiel.de; (T): 49-431-8804698; (F): 49-431-8803213; Christian-

Albrechts-University Kiel, Institute Ior Innovation Research, Westring 425, 24118 Kiel, Germany.

5()(5(1&(6

Aiken, L.S., West, S.G. (1992): Multiple regression. Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage. Newbury

Park, CaliIornia.

Almeida, P., Dokko, G., RosenkopI, L. (2003): Startup size and the mechanisms oI external learning:

Increasing opportunity and decreasing ability? Research Policv 32 (2), p. 301-315.

Ardichvili, A., Cardozo, R., Ray, S. (2003): A theory oI entrepreneurial opportunity identiIication and

development. Journal of Business Jenturing, 18 (18), p. 105-123.

Baum, J.A.C., Calabrese T., Silverman B. (2000): Don't go it alone: Alliance network composition and

startups' perIormance in Canadian biotechnology. Strategic Management Journal, 21(3), p. 267-294.

Bond, E.U., Houston, M.B., (2003): Barriers to matching new technologies and market opportunities in

established Iirms. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 20 (2), p. 120-135.

Bourgeois, L.J., Eisenhardt, K.M. (1988): Strategic decision processes in high velocity environments: Iour

cases in the microcomputer industry. Management Science, 34 (7), p. 816-835.

Bullinger, H.-J. (1990): F&E - heute. Industrielle Forschung und Entwicklung in der Bundesrepublik

Deutschland. IAO-Studie, Mnchen: gImt.

Page 7 oI 13

10/10/2011 http://Iusionmx.babson.edu/entrep/Ier/2007FER/cxxip2p.html

Calantone, R. Garcia, R., Droege, C. (2003): The eIIects oI environmental turbulence on new product

development strategy planning. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 20 (2), p. 90-103.

Campbell, D.T., Fiske, D.W. (1959): Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitrait-multimethod

matrix. Psvchological Bulletin, 56 (2), p. 81-105.

Chrisman, J.J., Hynes, T., Fraser, S. (1995): Faculty entrepreneurship and economic development: the case oI

the university oI Calgary. Journal of Business Jenturing, 10 (4), p. 267-281.

Cohen, W.M., Levinthal, D.A. (1990): Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation.

Administrative Science Quarterlv, 35 (1), p. 128-152.

Corbett, A.C. (2005): Experiential learning within the process oI opportunity identiIication and exploitation.

Entrepreneurship Theorv & Practice, 29 (4), p. 473-492.

Covin, J.G., Slevin, D.P. (1989): Strategic management oI small Iirms in hostile and benign environments.

Strategic Management Journal, 10 (1), p. 75-87.

DaIt, R., Weick, K. (1984): Toward a model oI organizations as interpretation systems. Academv of

Management Review, 9 (2), p. 284-296.

Day, G.S. (1994): Continuous learning about markets. California Management Review, 36 (4), p. 9-31.

Diamantopoulos, A., WinklhoIer, H.M. (2001): Index construction with Iormative indicators: An alternative

to scale development. Journal of Marketing Research, 38 (2), p. 269-277.

DorIman, N.S. (1983): Route 128: The development oI a regional high technology economy. Research Policv,

12 (6), p. 299-316.

Dougherty, D. (1990): Understanding new markets Ior new products. Strategic Management Journal, 11 (4),

p. 59-78.

Ernst, H. (2002): Success Iactors oI new product development: A review oI the empirical literature.

International Journal of Management Review, 4 (1), p. 1-40.

Fiol, C.M., Lyles, M.A. (1985): Organizational learning. Academv of Management Review, 10 (4), p. 803-813.

Geringer, J.M., Herbert, L. (1991): Measuring perIormance oI international joint ventures. Journal of

International Business Studies, 22 (2), p. 249-264.

Glazer, R., Weiss, A.M. (1993): Marketing in turbulent environments: Decision processes and time-sensitivity

oI inIormation. Journal of Marketing Research, 15 (4), p. 509-521.

Grant, R.M. (1996a): Towards a knowledge-based view oI the Iirm. Strategic Management Journal, 17

Special Issue, p. 109-122.

Grant, R.M. (1996b): Prospering in dynamically-competitive environments: Organizational capability as

knowledge integration. Organi:ation Science, 7 (4), p. 375-387.

Hamel, G. (1991): Competition Ior competence and inter-partner learning within international strategic

alliances. Strategic Management Journal, 12 (4), p. 83-103.

Hamel, G., Doz, Y.L., Prahalad C.K. (1989): Collaborate with your competitors and win. Harvard Business

Review, 67 (1), p. 133-139.

Han, J.K., Kim, N., Srivastava, R.K. (1998): Market orientation and organizational perIormance: Is innovation

a missing link? Journal of Marketing, 62 (4), p. 30-45.

Hansen, M.T., Nohria, N., Tierney, T. (1999): What's your strategy Ior managing knowledge? Harvard

Business Review, 77 (2), p. 106-116.

Harrison, R.T., Leitch, C.M. (2005): Entrepreneurial learning: Researching the interIace between learning and

the entrepreneurial context. Entrepreneurship Theorv & Practice, 29 (4), p. 351-371.

Hemer, J., Berteit, H., Walter, G., Gthner, M. (2006): Success Factors for Academic Spin-offs. Stuttgart:

FraunhoIer IRB Verlag.

Huber, G.P. (1991): Organizational learning: The contributing processes and the literatures. Organi:ation

Science, 2 (1), p. 88-115.

Iansiti, M. (1995): Shooting the rapids: Managing product development in turbulent environments. California

Management Review, 38 (1), p. 37-58.

Inkpen, A.C. (2000): Learning through joint ventures: A Iramework oI knowledge acquisition. Journal of

Management Studies, 37 (7), p. 1022-1043.

Jaworski, B.J., Kohli, A.K. (1993): Market orientation: Antecedents and consequences. Journal of Marketing,

57 (3), p. 53-70.

Jensen, R.J., Thursby, M. (2001): ProoIs and prototypes Ior sale: The licensing oI university inventions. The

American Economic Review, 91 (1), p. 240-259.

Jones-Evans, D. (1997): Technical entrepreneurship, experience and the management oI small technology-

based Iirms. in: Jones-Evans, D., KloIsten, M. (eds.): Technologv, innovation and enterprise. The

European experience, p. 11-60.

Kale, P., Dyer, J.H., Singh, H. (2002): Alliance capability, stock market response and long-term alliance

success: The role oI the alliance Iunction. Strategic Management Journal, 23 (8), p. 747-767.

Kim, D.H. (1993): The link between individual and organizational learning. Sloan Management Review, 35

Page 8 oI 13

10/10/2011 http://Iusionmx.babson.edu/entrep/Ier/2007FER/cxxip2p.html

(1), p. 37-50.

KloIsten, M., Lindell P., OloIIson, C., Wahlbin, C. (1988): Internal and external resources in technology-

based spin-oIIs. Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research, p. 430-433.

Kohli, A.K., Jaworski, B.J. (1990): Market orientation: The construct, research propositions, and managerial

implications. Journal of Marketing, 54 (2), p. 1-18.

Kumar, N., Stern, L., Anderson, J. (1993): Conducting interorganisational research using key inIormants.

Academv of Management Journal, 36 (6), p. 1633-1651.

Lane, P.J., Lubatkin, M. (1998): Relative absorptive capacity and interorganizational learning. Strategic

Management Journal, 19 (5), p. 461-478.

Larsson, R., Bengtsson, L., Henriksson, K., Sparks, J. (1998): The interorganizational learning dilemma:

Collective knowledge development in strategic alliances. Organi:ation Science, 9 (3), p. 285-305.

Lettl, C. (2004): Die Rolle von Anwendern bei hochgradigen Innovationen. Eine explorative

Fallstudienanalvse in der Medi:intechnik. Wiesbaden: Dt. Univ.-Verlag.

Li, T., Calantone, R.J. (1998): The impact oI market knowledge competence on new product advantage:

Conceptual and empirical examination. Journal of Marketing, 62 (4), p. 13-29.

Lockett, F., Wright, M., Franklin, S. (2003): Technology transIer and universities` spin-out strategies. Small

Business Economics, 20 (2), p. 185-200.

Lynn, G.S, Akgn, A.E. (1998): Innovation strategies under uncertainty: A contingency approach Ior new

product development. Engineering Management Journal, 10 (3), p. 11-18.

Lynn, G.S., Morone, J.G., Paulson, A.S. (1996): Marketing and discontinuous innovation: The probe and

learn process. California Management Review, 38 (3), p. 8-37.

March, J.G. (1991): Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organi:ation Science, 2 (1), p.

71-87.

Minniti, M., Bygrave, W. (2001): A dynamic model oI entrepreneurial learning. Entrepreneurship Theorv and

Practice, 25 (3), p. 5-16.

Narver, J.C., Slater, S.F. (1990): The EIIect oI a Market Orientation on Business ProIitability. Journal of

Marketing, 54 (4), p. 2035.

Nicholls-Nixon, C.L., Cooper, A.C., Woo, C.Y. (2000): Strategic experimentation: Understanding change and

perIormance in new ventures. Journal of Business Jenturing, 15 (5/6), p. 493-521.

Nonaka, I. (1994): A dynamic theory oI organizational knowledge. Organi:ation Science, 5 (1), p. 14-37.

Penrose, E. (1959): The theorv of the growth of the firm, OxIord: Blackwell.

Peters, M., Brush, C. (1996): Market inIormation scanning activities and growth in new ventures: A

comparison oI service and manuIacturing businesses. Journal of Business Research, 36 (1), p. 81-89.

Polanyi, M. (1958): Personal knowledge. Towards a post critical philosophv. Chicago, IL: University oI

Chicago Press.

Ravasi, D., Turati, C. (2005): Exploring entrepreneurial learning: A comparative study oI technology

development projects. Journal of Business Jenturing, 20 (1), p. 137-164.

Saemundsson, R.J. (2005): On the interaction between the growth process and the development oI technical

knowledge in young and growing technology-based Iirms. Technovation, 25 (3), p. 223-235.

Shane, S. (2000): Prior knowledge and the discovery oI entrepreneurial opportunities. Organi:ation Science,

11 (4), p. 448-469.

Sinkula, J.M. (1994): Market inIormation processing and organizational learning. Journal of Marketing, 58

(1), p. 35-44.

Slater, S.F., Narver, J.C. (1995): Does competitive environment moderate the market orientation-perIormance

relationship? Journal of Marketing, 59 (3), p. 46-55.

SteIIensen, M., Rogers, E.M., Speakman, K. (1999): Spin-oIIs Irom research centers at a research university.

Journal of Business Jenturing, 15 (1), p. 93-111.

Szulanski, G. (1996): Exploring internal stickiness: Impediments to the transIer oI best practice within the

Iirm. Strategic Management Journal, 17, Special Issue, p. 27-43.

Teece, D.J., Pisano, G., Shuen, A. (1997): Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic

Management Journal. 18 (7), p. 509-533.

Vohora, A., Wright, M., Lockett, A. (2004): Critical junctures in the development oI university high-tech

spinout companies. Research Policv, 33 (1), p. 147-176.

Von Hippel, E. (1986): Lead users: A source oI novel product concepts. Management Science, 32 (7), p. 791-

805.

Von Hippel, E., Tyre, M.J. (1995): How learning by doing is done: Problem identiIication in novel process

equipment. Research Policv, 24, p. 1-12.

Xie, W., White, S. (2004): Sequential learning in a Chinese spin-oII: the case oI Lenovo Group Limited. R&D

Management, 34 (4), p. 407-422.

Yli-Renko, H., Autio, E., Sapienza, H.J. (2001): Social capital, knowledge acquisition, and knowledge

Page 9 oI 13

10/10/2011 http://Iusionmx.babson.edu/entrep/Ier/2007FER/cxxip2p.html

exploitation in young technology-based Iirms. Strategic Management Journal, 22 (6/7), p. 587-613.

Zahra, S.A., Ireland, R.D., Hitt, M.A. (2000): International expansion by new venture Iirms: International

diversity, mode oI market entry, technological learning, and perIormance. Academv of Management

Journal, 43 (5), p. 925-950.

Zahra, S.A., Sapienza, H.J., Davidsson, P. (2006): Entrepreneurship and dynamic capabilities: A review,

model and research agenda. Journal of Management Studies, 43 (4), p. 917-955.

Zucker, L.G., Darby, M.R., Armstrong, J.S. (2002): Commercializing knowledge: University science,

knowledge capture, and Iirm perIormance in biotechnology. Management Science, 48 (1), p. 149-170.

Page 10 oI 13

10/10/2011 http://Iusionmx.babson.edu/entrep/Ier/2007FER/cxxip2p.html

Figure 1: Basic Research Model

H

1

H

3

Page 11 oI 13

10/10/2011 http://Iusionmx.babson.edu/entrep/Ier/2007FER/cxxip2p.html

Table 1: Descriptive Statistics and Correlations of Main Variables

Table 2: Regression Results (Standardized Coefficients)

Variables Mean SD MP PL CL KI DYN

1. Market PerIormance (MP) 5.19 0.79 1.0

2. Personal Learning (PL) 4.01 1.20 .33 1.0

3. CodiIied Learning (CL) 3.81 1.15 .17 .46 1.0

4. Knowledge Integration (KI) 4.85 0.91 .34 .43 .31 1.0

5. Technological Dynamism

(DYN)

3.53 1.67 -.02 .16 .10 .09 1.0

Independent Variable Market PerIormance

Main effects.

Personal Learning (PL)

a

.20

t

CodiIied Learning (CL)

a

-.12

Knowledge Integration (KI)

a

.20*

Interaction effects.

PL x Technological Dynamism .20*

CL x Technological Dynamism -.25**

KI x Technological Dynamism -.58

Control variables.

b

Prior Knowledge

c

-.03

Existing Customers

c .40**

Founders Teamsize

c

-.27

t

Technological Uncertainty

c

-.16

t

Technological Dynamism

c

.09

Time Start-up to Launch -.02

R

2

(adjusted R

2

)

.53 (.40)

AR

2

step three

.06**

F 4.08**

N 71

** p _ .01; * p _ .05;

f

p _ .10 (one-tailed test oI coeIIicients)

a

Data was provided by second key inIormant (e.g. project manager)

b

Industry and technology Iield dummies not reported.

c

Data provided Ior the time oI start-up.

Page 12 oI 13

10/10/2011 http://Iusionmx.babson.edu/entrep/Ier/2007FER/cxxip2p.html

Figure 2: Interaction Plot of Personal Learning and Technological Dynamism

Figure 3: Interaction Plot of Codified Learning and Technological Dynamism

Page 13 oI 13

10/10/2011 http://Iusionmx.babson.edu/entrep/Ier/2007FER/cxxip2p.html

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Math1041 Study Notes For UNSWDocument16 pagesMath1041 Study Notes For UNSWOliverNo ratings yet

- Society 11th Edition Macionis Test BankDocument61 pagesSociety 11th Edition Macionis Test BankAndreiNicolaiPachecoNo ratings yet

- Report On Cost EstimationDocument41 pagesReport On Cost EstimationTuhin SamirNo ratings yet

- The Racial Microaggressions Scale (RMAS) A New Scale To Measure Experiences of Racial Microaggressions in People of Color Torres-Harding2012Document13 pagesThe Racial Microaggressions Scale (RMAS) A New Scale To Measure Experiences of Racial Microaggressions in People of Color Torres-Harding2012Salman Tahir100% (1)

- NSD TestScoresDocument6 pagesNSD TestScoresmapasolutionNo ratings yet

- Relationship Between Patients' Knowledge and Medication Adherence Among Patients With HypertensionDocument8 pagesRelationship Between Patients' Knowledge and Medication Adherence Among Patients With HypertensionWina MariaNo ratings yet

- Spearman 1904aDocument31 pagesSpearman 1904amuellersenior3016No ratings yet

- Janset 2021 231Document5 pagesJanset 2021 231Misr RaymondNo ratings yet

- SPSS Pearson RDocument20 pagesSPSS Pearson RMat3xNo ratings yet

- 7 QC Tools TATA Motors PDFDocument76 pages7 QC Tools TATA Motors PDFRabi Chhetri Upadhyay50% (2)

- 10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2015.04.006: Journal of Corporate FinanceDocument51 pages10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2015.04.006: Journal of Corporate FinanceNayyabNo ratings yet

- Bowerman Regression CHPT 1Document18 pagesBowerman Regression CHPT 1CharleneKronstedt100% (1)

- Roger Nelson - Enhancement of The Global Consciousness ProjectDocument19 pagesRoger Nelson - Enhancement of The Global Consciousness ProjectHtemae100% (1)

- Geography Honours B.A. B.sc. SyllabusDocument38 pagesGeography Honours B.A. B.sc. SyllabusEllen GaonaNo ratings yet

- The Perception of Investors Towards Initial Public Offering: Evidence of NepalDocument11 pagesThe Perception of Investors Towards Initial Public Offering: Evidence of NepalSunisha PoudelNo ratings yet

- DWM CourseDocument67 pagesDWM Coursenaresh.kosuri6966No ratings yet

- QM II Formula SheetDocument2 pagesQM II Formula Sheetphanindra sairamNo ratings yet

- NTCC-Aditya Reddy PDFDocument28 pagesNTCC-Aditya Reddy PDFAditya Reddy VanguruNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document4 pagesChapter 1R LashNo ratings yet

- Taler - 2005 - Prediction of Heat Transfer Correlations For Compact Heat ExchangersDocument14 pagesTaler - 2005 - Prediction of Heat Transfer Correlations For Compact Heat ExchangersManikanta SwamyNo ratings yet

- (Cliffs Quick Review) George D Zgourides-Developmental Psychology-IDG BooksDocument155 pages(Cliffs Quick Review) George D Zgourides-Developmental Psychology-IDG BooksAndreClassicManNo ratings yet

- Maria Bolboaca - Lucrare de LicentaDocument68 pagesMaria Bolboaca - Lucrare de LicentaBucurei Ion-AlinNo ratings yet

- Ms. Neelam Nayak Pranali Mahajan: BackgroundDocument6 pagesMs. Neelam Nayak Pranali Mahajan: BackgroundYho Ghi GusnandaNo ratings yet

- Parametric Study of Charging Inlet Part2Document18 pagesParametric Study of Charging Inlet Part2mayurghule19100% (1)

- MIT - Stochastic ProcDocument88 pagesMIT - Stochastic ProccosmicduckNo ratings yet

- SAS IML User Guide PDFDocument1,108 pagesSAS IML User Guide PDFJorge Muñoz AristizabalNo ratings yet

- Practical Research 2: Schools Division of Bohol: 4: 7: 7Document2 pagesPractical Research 2: Schools Division of Bohol: 4: 7: 7Jown Honenew Lpt0% (1)

- Promoting Interpersonal Compeence and Eduactional Success 2003Document11 pagesPromoting Interpersonal Compeence and Eduactional Success 2003morpheus_scribdNo ratings yet

- Balcanica XXXIX 2008Document316 pagesBalcanica XXXIX 2008ivansuvNo ratings yet

- Environment and Behavior 2009 Gustafson 490 508Document20 pagesEnvironment and Behavior 2009 Gustafson 490 508Silvana GhermanNo ratings yet