Professional Documents

Culture Documents

10 Chansky StitchInTime

Uploaded by

Christine WeberOriginal Description:

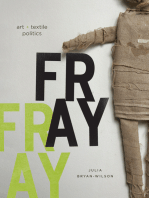

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

10 Chansky StitchInTime

Uploaded by

Christine WeberCopyright:

Available Formats

A Stitch in Time: Third-Wave Feminist Reclamation of Needled Imagery

RICIA A. CHANSKY

with the dominant majority, they tend to cast off symbols that mark their difference, under the ideology that it is these external signs which divide them. Certain symbols may be reclaimed as some semblance of power is gained by the minority group, upon the realization that part of their historical roots have faded in the rush to downplay differences. As Third-Wave feminists explore the power afforded them from the womens movement, they are moving to reclaim many of the domestic arts that were both devaluated by the predominant masculine society and shunned as associative with oppressive domestic labor by many Second-Wave feminists. Paramount in this reclamation movement is the overwhelming trend among women in their twenties and thirties to utilize needled works as feminist expression. These women are returning to domestic arts such as knitting and quilting with a sense of strength, not servitude, viewing the needle as a means of creative outlet that communicates their individual strength. Many women see this current textile revolution as the actualization of personal choice that Second-Wave feminists fought so hard for. Betsey Greer, founder of craftivism.com, believes that feminism is having the choice to cook dinner or heat up something prepackaged, and that this is demonstrated in the current Third-Wave return to the domestic arts through the choice to make something by hand or buy it (Sabella 2). The needle and all of the textile arts achieved through the use of a needle, including knitting, crocheting, sewing and quilting, latch or rug hooking, embroidery, and cross stitch, seem to be apt visual metaphors for Third-Wave feminists. Growing up in the punk and Riot

The Journal of Popular Culture, Vol. 43, No. 4, 2010 r 2010, Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

S MARGINALIZED GROUPS WITHIN SOCIETY STRUGGLE FOR EQUALITY

681

682

Ricia A. Chansky

Grrl movements which fought to reclaim so many aspects of traditional femininity in powerful new ways, Third Wavers have been beset with an exploration of female power and pride intertwined with pre- and postfeminist imagery. The needle is an appropriate material representation of women who are balancing both their anger over oppression and pride in their gender. The needle stabs as it creates, forcing thread or yarn into the act of creation. From a violent action comes the birth of a new whole. Women are channeling their rage, frustration, guilt, and other difcult emotions into a powerfully productive activity. The dichotomy is, of course, that their means of creation grow out of a female-centered tradition that has often been associated with domestic oppression. Fortunately, Third Wavers have sat at their mothers knees long enough to have learned their feminist lessons. The current movement to express oneself through needlework recognizes the irony of using the domestic arts to express contemporary thoughts. Women are both discussing very contemporary issues in their work and incorporating unusual materials and methods into it. Reclamation in this arena does not simply recreate these traditional art forms but rather uses historically undervalued means of artistic expression to discuss very contemporary issues in fresh new ways. One of the primary strengths of needled imagery is its ability to take viewers completely off guard. Needlework often carries associations to the home, older generations of female relatives, and the security of items made for comfort, so works discussing heady sociopolitical issues delivered in this forum welcome viewers into communicating with the ideas presented, instead of automatically turning away from them out of discomfort. This contradiction of terms, comfort and discomfort coexisting in the same work of art, allows Third-Wave feminists the ability to act up in what is typically recognized as an everyday arena. This indirect activism is one of the demarcations of Third-Wave feminism. According to political activist/journalist Kristin RoweFinkbeiner, and echoed by countless other feminist theorists, the essence of third-wave philosophy . . . is that real social change is achieved indirectly through cultural action, or simply carried out through popculture twists and transformations, instead of through an overtly political, electoral, and legislative agenda (Rowe-Finkbeiner 88). Third Wavers do not necessarily see the need for marches and rallies, as they have grown up enjoying the hard-won liberties that their mothers and grandmothers fought for. Their brand of activism seems to be a more

A Stitch in Time

683

everyday, everyway movement that executes a perhaps less noticeable but more prevalent sense of feminism in their day-to-day lives. While this philosophy certainly plays against a Second-Wave ideal of public activism and creates certain communication difculties between the two generations of feminists, it tends to be a positive force in such arenas as the contemporary craft as activism movement, sometimes referred to as craftivism. Many women making their own clothing and goods view the process as a pointed statement against factory-constructed items that take advantage of cheap labor, especially women and children. Founder and editor of ReadyMade magazine, Shoshana Berger, noticed a glut of cheap sweatshop-produced clothing that has led her to provide over 100,000 subscribers with a variety of fashion and home DIY ideas (Stukin 3). She believes that not only are people recognizing that this mass-produced stuff is unimaginative, but theyre also feeling guilty about supporting unfair labor practices (3). Craftivism also plays out in a more direct manner. Many women involved in a large scale in the craft world work with nonprot organizations. For example, the Fiber and Craft Entrepreneurial Development Center sponsors a program called Rwanda Knits that sets up knitting collectives for women in that war-torn country, leading to economic freedom and a brighter future (Clement 1). Domestically the Warm Up America! Foundation, in conjunction with the Craft Yarn Council of America, organizes crafters and crafting organizations to make blankets for victims of natural disasters, battered womens shelters, and the homeless, among others (56warmupamerica.com 1). Craft has also taken on an important role as a method of mourning as public activism. The power of the AIDS Quilt spread out over The National Mall is an undeniable visual force that orders us to reect on the horrors of our modern epidemic. Feminist theorist Elaine Showalter explains that in the AIDS Quilt we see the continued vitality of the quilt metaphor, its powers of change and renewal, and its potential to unify and heal (174). Subversive Stitch founder Julie Jackson, and author of the new book Subversive Cross Stitch: 33 Designs for Your Surly Side, sells a cross stitch kit that spells out Fuck Cancer. She reports that this kit consistently receives positive feedback from her customers and admirers. She frequently gets touching emails about how that sentiment has reached people going through chemo or the people supporting them . . . [she]

684

Ricia A. Chansky

think[s] it lets them express their anger in a humorous way . . . and keeps the sales from that item attached to a cancer charity ( Jackson 1). Stacie Stukin, an analyst for Time Magazine, believes that beyond this charitable nature, a push toward individuality is also responsible for the resurgence of crafters. She thinks that the movement is driven by style-conscious women who are bored by the cookie-cutter apparel sold at stores like Gap and Banana Republic (Stukin 1). Author and crafter Jennifer Traig tells her readers that anybody can buy stuffit takes a crafty girl to fashion a one-of-a-kind, awe-inspiring, trendsetting treasure (8). Additionally, in a time when many women are actively trying to work against culturally regimented ideals of feminine beauty and have healthy body images, the act of creating ones own clothes is a way to have funky, expressive clothing that ts well despite the limitations of mass-produced clothing that tends to be made for specic body sizes and shapes. Big Girl Knits: 25 Big, Bold Projects Shaped for Real Women with Real Curves by Jillian Moreno and Amy R. Singer offer projects specically tailored for busty and bootilicious babes (Graham 104). Self-proclaimed fat girl Beth Ditto told BUST that knowing how to make DIY clothing allows her to say Fuck off. Thanks for making clothes that dont t me to stores that do not carry her size (38). A very empowering statement for a woman who is trapped by an unrealistic societal standard propagated by a media-based culture. Moreover, it can be nigh on impossible for a Third-Wave feminist to envision herself purchasing frilly pink, gender-stereotyping dresses for her old college roommates new baby, when her fondest memories of them together involve slamming in the mosh pit at The Channel. Third-Wave feminists who grew up knowing that pink is a choice, especially those who align themselves with a postpunk aesthetic of individualism as beauty, are reveling in the DIY movement that allows them to create unique goods that express their personalities. These Third-Wave ideals reect such art trends as the International Arts and Crafts Movement that rebelled against the Industrial Revolution and the mass production of household goods, just as the contemporary needled rebellion ghts against a standardization of fashion and domestic goods. The Arts and Crafts Movement was built upon feelings of distress growing from the rise in machine-made goods and the decline in craftspersonship. Craftspeople such as William Morris wished to reintroduce the beauty of handicraft to Victorian society and

A Stitch in Time

685

better the working conditions of factory laborers, struggling to keep up with societal demands for mass-produced goods. Additionally, Morris was concerned with the pervasive decorating ideal that promoted fussiness and clutter and rather touted a simple, individualized design aesthetic (Wissinger 9). Glenna Matthews, a professor at the University of California at Berkeley and author of Just a Housewife: The Rise and Fall of Domesticity in America, states that there is a cyclical rebellion against everything being machine made (Sabella 2). It is a likely possibility that the current rage against the machine has grown from some very real nancial needs. With their limited semiadult budgets, Third Wavers have scoured secondhand stores for cool clothes, aided by haute couture designers reclaiming vintage designs: the shift, bellbottoms, even the swing dress have made reappearances on the mainstream fashion radar. Kitch has become a way of life, both as an economic necessity and as a means of expressing individual style. Entrepreneur Michelle Zacks of M. Z. boutique sells her original interpretations of vintage-style sweaters that are highly wearable and affordable, alongside actual vintage sweaters (McCombs 34), and she is not the only one mixing handmade items with vintage. Books such as Second Time Cool: The Art of Chopping Up a Sweater and Tease: 50 Inspired T-Shirt Transformations by Superstars of Art, Craft and Design guide newbies through the art of secondhand or second-life fashion reclamation. These Third-Wave feminists who utilize needled imagery to creatively express themselves and their individuality certainly owe a large dept to the Second-Wave feminists who actively reclaimed women artists and womens arts in the 1960s and 1970s. Feminist artists, art historians, and critics set about nding their foremothers in an art tradition that drew a clear and insurmountable line between art and craft, stating that anything created for utilitarian purposes was craft and therefore not as valuable as art created purely for aesthetic sensation. Unfortunately, it seemed that women throughout history were primarily relegated to the craft world, making their artistic efforts less valuable than those traditionally pursued by men. Needled works, such as quilting and embroidery, certainly fell into this craft realm that was downplayed and undervalued by mainstream society. Feminist art historian Lisa Tickner explains that feminizing textile art keeps womens work marginal and identies it with the characteristics of a reproduc-

686

Ricia A. Chansky

tive and femininity, which are understood not to be the characteristics of great art (Showalter 147). In reaction to the devaluation of womens arts, the womens movement recovered positive historic and artistic role models and reclaimed textile art, particularly weaving and quilting, as an art form. The argument was that these pieces were created at a very high skill and aesthetic level and should therefore be viewed as successful works of art despite their traditionally being produced for functional purposes. In her pivotal speech Common Threads, Showalter states that several American women artists such as Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro found new artistic inspiration and self-validation in womens needlework (161). This reconnection to traditional womens arts gave contemporary artists a sense of pride in the historical traditions of women and a foundation to build upon with their own work. Radka DonnellVogt, a master quilter featured in the documentary Quilts in Womens Lives, states that the piecing tradition in quilt making is a primal womens art form, related to the body, to mother-daughter bonding, to touch and texture, and to the intimacy of the bed and the home (162 63). Textile arts formed a link to the past that allowed women to reevaluate their foremothers with a sense of pride and allow them to grow from domestic traditions with satisfaction, rather than shame. Furthermore, as Showalter explains, the technique of piecing a quilt is a perfect reection of a womans creative life, as she is continually forced to snatch the small amounts of time parceled out to her for creative work, and make a whole creative project from these tiny pieces (145 75). Feminist art critic and theorist Lucy Lippard supports this theory, explaining that the quilt has become the prime visual metaphor for womens lives, for womens culture (161). Both Chicago and Schapiro took this rediscovery of needled imagery to heart, incorporating textiles into their early feminist artworks. Chicagos impressive installation, The Dinner Party, incorporates several quilting, applique, and embroidery techniques into the mats at each place setting. With its clear references to The Last Supper, The Dinner Party elevates female tradition to a heroic scale traditionally reserved for men (Chicago 8), which by association raises the included textile art to a similar level of respect and glory. The Pacic Science Center in Seattle, WA, even tried to book the installation for exhibition on the grounds that they felt it was a successful chronicle of the history of textiles in the needlework (Chicago 8).

A Stitch in Time

687

While certainly less of a media personality than Chicago, Schapiro has perhaps been a more direct inuence on the needled Third-Wave feminist movement. In the 1970s, she began making collages that incorporated both printed and embroidered fabric scraps into her work, primarily from domestic-centered textiles such as tablecloths, curtains, and aprons (Robinson 128). She coined the term femmage for these works, to make it clear that this incorporation of traditional womens domestic symbols were an integral, underlying part of her work (128). As a leading member of the subsequent Pattern and Decoration movement (P and D), she built upon her exploration of textiles through investigation of the traditional role of women in the decorative arts (Robinson 128). Art historian Sandra Sider thinks that the art world is currently in a P and D revival, demonstrated by the number of younger artists creating complexly decorated surfaces, patiently stitched with objects and images. She sees a further connection between the art quilt movement and P and D, explaining that it carries on a quilting tradition while experimenting with unorthodox materials and painterly patterning (Sider 1), an egalitarian meeting of womens past and present. Art historian Christopher Miles discusses the continuation of Schapiros themes and techniques in contemporary movements stating, Pattern and Decoration might then be seen not as the exception or counter to dominant high modernism, but as the expression of an enduring decorative and appropriative impulse, and an essential if underacknowledged impetus behind the 80s resurgence of painting and the pluralist freedom that has dened art since (Sider 2). When Chicago and Schapiro created the germinal installation Womanhouse in 1972 with their students from the Feminist Art Program at the California Institute of the Arts, they wanted to create a series of fantasy environments exploring the various personal meanings and gender constructions of domestic space (Chicago 1). If SecondWave feminism creates any dichotomies in the art versus craft debate that Third-Wave feminists have to struggle through and come to terms with, it is perhaps this idea that domesticity was so eschewed as a patriarchal oppressor that any crafts not separated out and claimed by the art world were associated with this domestic oppression. While Faith Wildings Crocheted Environment at Womanhouse does use crocheting as a medium, the majority of the works relate

688

Ricia A. Chansky

to the bonds of domestic activities. Feminist art critic Lucy Lippard claries that women make art to escape, overwhelm, or transform daily realities . . . so it makes sense that those women artists who do focus on domestic imagery often seem to be taking off from, rather than getting off on, the implications of oors and brooms and dirty laundry. They work from such imagery because its there, because its what they know best, because they cant escape it. (56) Unfortunately, this revulsion toward domestic chores has a lingering connection to certain traditional womens crafts, including knitting, cross stitching, rug hooking, and crocheting. These crafts were tasks that Third-Wave feminists were brought up to believe our grandmothers practiced, not hip, young women. Many contemporary crafters are deliberately separating themselves from this association, trying to overcome the lingering negative stereotype crafting has in the feminist realm. Jenny Hart, embroidery artist, and owner of the online embroidery pattern business Sublime Stitching, markets her designs as Finally! Cool craft patterns! This aint your grammas embroidery! This upfront, reclamation tone is echoed in the name of the all women craft group in Texas, the Austin Craft Maa, and in the name of my personal favorite craft festival, the DC-based Crafty Bastard, and countless other feminist craft groups. A good deal of this longing for cool craft grows from a variety of career-related issues that combine to create a general malaise with the business world which entices Third-Wave feminists to ock full force to the popular contemporary womens craft movement. Many twenty- and thirty-something women came of age watching their mothers enter the workforce and struggle for their place of respect in a career-oriented society. They grew up expecting that when their turn came, they would nd glamorous, high-paying jobs that would win them public accolades and private fulllment. Unfortunately, young feminists have often been dramatically surprised and disappointed upon entering the work world. The most prevalent realization seems to be the surprising insight that in the twenty-rst century a college education does not automatically equal a powerhouse career accompanied by a high salary and esteem from peers and loved ones alike. Rather, a college degree often results in a lowpaying, entry-level position as a clerical aid or administrative assistant. In her article Living in McJobdom: Third Wave Feminism and Class

A Stitch in Time

689

Inequality Michelle Sidler bemoans the curse of the McJob on young people with college degrees, but without graduate degrees, admitting that one of the greatest motivators in her pursuing a doctorate was her own fear of facing a bleak job market holding, as [she] did, few technical skills and a liberal arts degree (25). She states that the majority of her friends and peers were working in part-time or temporary positions with no benets and no hope of advancement (Sidler 25 26). Ellen Bravo, in her essay The Clerical Proletariat, reminds us that despite the level of education, non-management administrative support remains the largest occupational category for women . . . nearly one in four of all employed women . . . in 2002 (349). According to Bravo, this level of employee is often viewed as the ofce wife and their job description is rarely set in stone, but more likely adjusted as needed (350). Often times the clerical aid must be highly skilled in technology, but her wages are not commensurate with this criterion, nor is she treated with the due respect (350 51). There is indeed little fulllment offered from a position that affords unequal compensation to workers and oftentimes does not utilize hard-won skills and information that employees have in their eld of interest. Crafters Debbie Stoller and Julie Jackson both report being frustrated in their nine-to-ve employment forays. Jackson freely discusses her interest in cross stitch growing out of a need for a form of anger management therapy when [she] was dealing with an idiot boss (3). Similarly, Stoller, a founding editor of BUST: For Women with Something to Get Off Their Chests and the author of two books on knitting and one on crocheting, refers to herself and her cofounding editor Marcelle Karp as a couple of overeducated, underpaid, late-twenty-something cubicle slaves, working side-by-side at a Giant Media Conglomerate (xii). In frustration over their cubicle slave lives and concern over the lack of a clear and present feminism in the early 1990s, the two began BUST as a zine photocopied after hours at the Giant Media Conglomerate (Baumgardner and Richards 148). Additionally, the professional career, whether it be on the entrylevel, mid- or high-level management, typically does not equate the construction of any tangible object that one can take pride in. It can be very frustrating to spend the majority of ones life at an ofce and not see a product that can be held, examined, or shared as the fruit of those efforts. The sense of ennui is prevalent through young professionals, especially those who wish to remain loyal to some perceived sense of

690

Ricia A. Chansky

ethics and individuality, something that the contemporary cubicalstyle of business rarely allows. Stitch and Bitcher Jennifer Small is a software designer who states in Stitch n Bitch Nation that knitting is a great way for [her] to be creative with [her] hands and not just [her] brain (Stoller 215). Likewise, member Stitch and Bitcher Christine Quirion relates how knitting and crafting have added a dimension to [her] life that [she] didnt even know was missing (76). Matthews also states that there is something about crafting that offers an immediate satisfaction, which might be why the women consumed by a very on-the-go mind draining culture take refuge in these activities. In itself, escape from their own monotonous day-to-day life may be an activist venture for some women. She further declares that as machines [have] taken over more and more of our work and computers more and more of our brainwork, the kind of immediacy of craft-oriented work is very rare. (Sabella 3) Tantamount to the rude awakening young feminists are nding themselves in at the ofce is the issue of women from a certain socioeconomic class and/or education level being expected to engage in a professional career, but not expected to give up the majority of their household chores, resulting in the dreaded superwoman syndrome. While progress has certainly been made in dividing the chores between partners, there is still a prevalent inequality between domestic care and upkeep that discriminates against women. According to Sue Barton, a psychologist with the Department of Family and Community Medicine at UC Davis Medical Center: research indicates that for men, coming home from work usually means an end to the primary source of stress for the day. But for women, leaving work offers no refuge. If the house is a mess and food isnt on the table, many women feel it reects on their abilities as an adequate wife or mother. And if marital relations are strained or kids arent doing well, women tend to internalize these problems, feeling they are due to some failing of their own. (1) Linked to this superwoman syndrome is a high level of guilt that is primarily associated with a feeling of failure to complete expected domestic tasks, such as cooking, cleaning, and childcare. The expectation that modern women work outside of the home is complicated by the ongoing ideals of motherhood, wifedom, and an expected level of housekeeping. Balancing the two identities of professional employee

A Stitch in Time

691

and domestic goddess can be quite confusing and even overwhelming. Working mothers guilt plays upon this unfounded sense of failure women experience when spread thinly between work and home life. Sarah Max, CNN/Money senior writer, sees a great deal of guilt and confusion prevalent in the American working mother, especially in regards to the need for daycare services and the constant juggling of kids and career (1). Akin to this working mothers guilt is perhaps Third-Wave feminists very salient recollections of being latchkey kids when their own mothers entered the workforce, leading to a uncomfortable remembrance of microwavable frozen dinners, televisions as babysitters, and a vague sense of missing an integral part of their childhoods. A personally owned, online business allows one the opportunity to work from home and to pursue a less rigid or formal schedule. While this may not be an ideal solution to the problem of managing life as both a mother and a professional, it does allow women to pursue their interests for economic gain and spend more time at home with their children, alleviating some of the working mothers guilt. Vicki Howell, self-proclaimed craft grrl, author of New Knits on the Block: A Guide to Knitting What Kids Really Want, host of the DIY Network program Knitty Gritty and cohost of Stylelicious, also founded and runs three separate Internet businesses. Howell is the mother of two young children and switched from work in the entertainment business to Web retail after their birth. Her rst forays, including mamarama.com, catered to young, hip mothers who also wanted unique, handmade products for their kids. She rmly believes in knitting as a feminist action and actively supports other female-run, craft-based businesses (Howell 4). Additionally, Howells Web site offers t-shirts with such rebel crafter slogans as berwhore and craft.rock.live. Finally, several crafters report that their interest in knitting and/or other textile craft forms came about as a result of the rise and fall of the dot.com industry. When the heady ux of the dot.com businesses wore off and young professionals working for large Internet-based companies were downsized into a tight economy, there was a clear need for positive activities to keep idle hands busy; especially activities that resulted in a tangible end product that one could feel proud of in difcult times. Stitch and Bitcher Shannita Williams-Alleyne explains that she is a former marketing executive who learned to knit in the

692

Ricia A. Chansky

aftermath of the Great Dot-com Crash of 2001. With a severance package and too much time on [her] hands, [she] picked up two sticks and some string and never looked back (Stoller 69). She now works at a knit shop and sells her own designs online. The current craft movement is certainly not the rst time that large groups of women have considered the possibility of being their own bosses in a craft-related business. In the 1960s and 1970s there were a number of art and craft collectives or co-ops that were staffed and stocked by women. The problem was that a group of women had to raise the capital to rent or purchase a location, pay the overhead on the property, and staff the store. Most of the workers in these collectives were volunteers who had to work in the shop and therefore donated their time to help the business succeed, but this often inhibited their pursuit of other money-making enterprises. This was, of course, a difcult means of survival for the majority of women involved, and these businesses were often unsustainable due to the sheer amount of prot needed to pay bills and eek out a prot. The advent of the Internet and young womens high level of literacy with Web technology is a factor that negates the overwhelming responsibility of locating a store in a physical realm. The economic outlay for a Web site is nominal and with the advent of the eBays store and PayPals technology that small business can link into for consumer and sellers safety with credit card sales, opening a business is much simpler for Third Wavers than it was for our Second-Wave predecessors. Moreover, the small monetary outlay needed for an Internet business allows women to keep their day jobs, so to speak, as they experiment with owning a small business. A woman beginning her own business in this arena can hold on to the security of a regular paycheck and benets while their online store gets up and running. Jesse Kelly-Landes, cohost of the DIY Networks show Stylelicious and owner of the online made-to-order clothing company Amet and Sasha, states that the internet has been extremely important to [her] and [her] business. It allowed [her] to try something without investing thousands of dollars in it. [She] was able to see [she] could do it, without the commitment (1). Furthermore, new software, such as Dreamweavers, makes Web site building extremely accessible for people who do not have prior instruction in Web building and/or graphic design. The lower price of

A Stitch in Time

693

digital cameras, scanners, and computers themselves makes this a more accessible means of showing their wares for many women. A number of young crafters also exchange Web design and/or maintenance for goods, putting the age-old barter system into practice. Quirion reports that she traded a knitting lesson for introductory instruction in computer graphics (Stoller 76). An additional fee that becomes dramatically lowered when one opens a virtual store is that of advertising. A majority of these online stores offer visitors the option of signing up for an online newsletter. At regularly scheduled intervals, interested parties receive e-mails advertising sales or new products. This is a very interesting and virtually free means of bypassing the expenses involved with traditional mailers, including design, printing, and mailing costs. Another intriguing aspect of these new women-owned online businesses is the phenomenon of linking. It is quite ordinary these days for a Web site to offer a direct link to other Web sites with similar or complementary content. What is unusual is the way that young female business owners are working together for a common good. Many young women understand that even with the possibilities for economic success on the Internet available to them, that they need to work together if they are to achieve economic freedom in this arena. The links that take viewers from one Web site to another are both a means of advertising and supporting one another as they take the fearful leap into the unknown eld of small business ownership. Leah Kramer, founder of craftster.org a nonprot Web community for crafters to communicate, share, and support each other, reports that the Web site has over twenty thousand registered members and 250,000 visitors per month (Stukin 2). She states that there are no fees to join the site and that nothing is sold on it, rather its purpose is to create a sense of community among crafters (Stukin 2), perhaps acting as an electronic sewing circle for the technological era. While many women are becoming involved with craft on a smaller level, the variety of Web businesses that women have started with a myriad of different crafts is intriguing, especially as it equates levels of political activism and economic freedom for these women. Whitney Lee, owner of the online business Made with Sweet Love, is a rughooker who recreates pornographic images in her medium. She began the project because of a dislike of the ways in which women were portrayed in the mass media but wanted to incorporate irony and

694

Ricia A. Chansky

humor into her artistic statement (Lee 1). She now sees her work as less of a criticism on society and more of a part of the larger dialogue on feminism, pornography, and stereotypical beauty images (1). Lee is using a highly traditional womans craft, that had a previous reclamation in the 1970s and 1980s, to convey her very serious message of antiobjectication. For many women who would be potentially uncomfortable with such stark imagery, Lee offers the image and the message in a less threatening manner, allowing viewers to more comfortably approach the work and examine it. In addition to her original work, Lee sells rug-hooking kits on her Web site. Jenny Hart of Sublime Stitching says that she began embroidering as a reaction to the way that her generation had largely ignored needleworking due to an overabundance of bunnies and dull, outdated instructions (1). Hart has both a Web site where she sells her original work and stitching kits, and a book titled Sublime Stitching published by Chronicle Books. Her original embroidery works of pop culture icons, such as Dolly Parton and Marianne Faithful, are collected by international museums, galleries, and individuals, and she has appeared as a celebrity judge on Craft Corner Death Match, shown on E! and the Style Network. Her offered designs include images from the roller derby (also currently being reclaimed by Third Wavers), sushi bar, Day of the Dead, Goth underground, and yoga studio. Harts work acts as a double reclamation, as she is also very focused on memorializing the personalities that shaped her childhood. There is a lovely portrait of Donny and Marie on the Web site, and she chooses to do the work in a very traditional medium: a true mixture of traditional craft and pop culture morphing kitsch heroes into iconography that memorializes and celebrates a personal tradition of 1970s low culture. While a number of women are gaining their economic freedom through Internet craft businesses, there is certainly a difference between those individuals and the majority of women who are utilizing craft projects on a smaller level to alleviate stress and express their creativity. Uber-Third-Waver Stoller has a collection of published works to induct virgin knitters into the cult of craft, including Stitch n Bitch: The Knitters Handbook, Stitch n Bitch Nation, Stitch n Bitch: A Knitters Journal, and The Happy Hooker: Stitch n Bitch Crochet. These texts have spawned an international ux of Stitch and Bitchers meeting on a regular basis to knit, bitch, and generally share

A Stitch in Time

695

in a positive, supporting, feminist community. Even the Feminist Majority Leadership Alliance regularly sponsors Stitch and Bitch meetings. Vogue, which has a long tradition of providing women with fashionable sewing and knitting patterns, inaugurated a new knitting magazine for these young, hipster knitters called Knit.1. The Spring 2006 issue boasts an article about the skatepunk, screamo band Thrices lead singer Eddie Breckenridge crocheting on the road, one about knitting international designs and vintage-style stewardess uniforms full of irony, and another touting pirate motifs on knitwear. The language is hip and sexy; one article promoting knitted projects for travels is titled The Mile-High Club, with a clear reference to just how sexy knitting is. In addition to the more formal or published resources for women interested in craft as relaxation, creative self-expression, and/or activism, there are a number of other Web resources that act as information sites and/or supportive havens. Sites such as femiknit.maa. blogspot.com, feminista.blog.com, knitpixie.com, knit.activist.ca, and knitheaven.com (and this is just a very small sampling of the many available sites) discuss craft as a feminist expression. Yarn stores are also becoming part of the feminiknit movement. Flying Fingers knitting supply of NY advertises that they Believe in Freedom of Choice!, a rm feminist slogan applied to yarn selection as well as sociopolitical policy that upholds the Third-Wave mentality of everyday, everyway activism. A number of women also refer to knitting as the new yoga, touting its power to relax and calm. In the original Stitch n Bitch, Stoller mentions a member of her knitting group who began knitting as a way to soothe her nerves after having escaped from the seventy-ninth oor of the World Trade Center on that day in September (113). She also lists celebrity knitters who knit to relax, including Cameron Diaz, Tyra Banks, and Sarah Jessica Parker (Stoller 8). While crafters are certainly the most prevalent reclaimers of needled imagery, there is a movement of ber artists which grew out of the Second-Wave ideals of appreciating quilting and weaving as high art. Ulla Pohjola, a Finnish ber artist who uses traditional means of womens artistic expression and cultural materials and methods to express her very modern ideals, who epitomizes reclamation theory. She not only excels at the textile arts, quilting, and embroidering her craft

696

Ricia A. Chansky

for display, but also incorporates traditional Nordic craft techniques such as dyeing fabrics and yarns by hand and felting. In addition to reclaiming gender and cultural domestic art traditions, Pohjola often incorporates technology into her fabric designs. Pohjola, in cooperation with her sister Helena Pohjola, created a wedding dress named Jupiters Bride: Winter Wedding Dress in consideration of a modern Finnish bride. The sisters came up with the idea for the gown made of felted white wool while visiting their grandmothers sheep farm. The two were frustrated with the number of satin wedding gowns sold during the notorious cold of their native homeland and wanted to attempt to make the extremely warm wool felting as attractive as satin. In addition to their ultimate success with the felting process, Ulla had the idea to incorporate optical cables with light illuminating diodes into the design for a magical glow. She states that the cables were incorporated to add light and life to the long, dark Finnish nights and bring as much joy as possible to a wedding day (Pohjola 1). The dress is truly a marriage of tradition and technology, reclamation of conventional domestic arts reinterpreted with attention to modern means and attitudes. English ber artist Tracey Emin is known as the bad girl of the British art world. She is perhaps best known for her appliqued blankets and a 1995 installation titled Everyone I Have Ever Slept With, constructed from a nylon tent with applique and a light. Every person who Emin had ever shared a bed with until the work was created is listed inside with notes and recollections, even friends and family members that she was just sleeping beside. The statement that they have all remained with her is quite intriguing, and the tent presents a wonderful metaphor for the human heart, retaining each memory (positive or negative) of those who have shared her bed. Art critic Melanie McGrath discusses the pervasive strength and power of Emins work in a recent article for the Tate Magazine, stating that Emins insistence is part of her power . . . Emin is dangerous. She shouts, she often bullies, she will not let you look away (1 4). McGrath also comments on the dichotomy of utilizing traditional domestic arts to discuss difcult contemporary issues. She states that the work is comfortingly dangerous. It is at one and the same time subversive and conservative . . . It allows her to reach beyond the academy. It tells of life the way life is. Most of all, it keeps me interested (5 6).

A Stitch in Time

697

McGrath also reports her exchange with two male critics who were quick to dismiss the work and even insisted on mispronouncing her name. McGraths sense was that these were not unconscious gestures, but whether they were or not, they were indicative of some covert desire to discount the woman and, by implication, her work (7). Perhaps there is a lingering sense of discomfort with Emins famous blankets. One of the most colorful is the 1999 Psycho Slut. In these works, the artists appliqued words are quite blunt, expressing a fear of publicly discarding waste and how that may inuence peoples perception of her sexuality. In Psycho Slut Emin uses piecing techniques and appliqued letters. The line becomes blurred between ber artists and artists who use ber in their work, but a good example of the latter is Ghada Amer who uses thread as paint on a canvas. Amer, born in Cairo and currently residing in New York and Paris, is a perfect example of a ne artist incorporating the needle into traditional forms of two-dimensional artwork, painting with thread. Amer uses stitching to express ideals of womens freedom on canvas. Best known for her large-scale embroidered paintings reminiscent of abstract expressionism, Amer has also produced a number of important installation works that use embroidered script (nmafa.si.edu). One of her most famous works, Encyclopedia of Pleasure, refers to a medieval Arabic sexual and spiritual fulllment manual, which was widely accepted in the tenth or eleventh century when it was published, but lost favor as society became more conservative. Amers work utilizes 57 canvas boxes, covered with Roman script embroidered in gold thread and stacked in various arrangements. The text of these passages is not important per se but acts merely as the visual framework for larger investigations of sexuality and spirituality and the role of the word within them. . .which discuss issues of female pleasure and beauty (nmafa.si.edu). The theme of exploring a womans sexuality is continued in her 1999 series of embroidered works including Untitled, La Jaune, and Big Drips and shows a series of smiling women masturbating. While the women are not at rst clear to the viewer, as they materialize there is a sense of normalizing the act through the repetition of the image and its presentation in such a traditional art form. Art historian Uta Grosenick sees the repeated gures as presenting masturbation as if it were a typically female pastime (30). The repetition of these

698

Ricia A. Chansky

images, in which the women easily meet the eyes of the viewer, sends a message of comfort with sexuality in a positive manner, rather than a lascivious or pornographic way. This is easily reective of a common Third-Wave point that women have the right to express their sexuality in a positive, healthy way. Amer began stitching on canvas by recreating traditional clothing patterns. She noted that they all related to a stereotypical ideal of female physical perfection, one that she believes has become rooted in the psyche of women as a subconscious ideal that they need to strive toward. This later work examining sexuality grows out of a desire to examine the prescribed boundaries of female sexuality (Grosenick 35). The Third-Wave postpunk aesthetic seems ideally suited for an art form that allows practitioners to stab as they create. This method seems like an ideal reection of our upbringing, done under the watchful eyes of our proud feminist mothers who were actively ghting to tear down gender inequality while simultaneously building a better, more equal society. It lets us discuss our sociopolitical concerns, especially our complex relationships with our own sexuality, in a safe and comforting arena, perhaps our only true means of expressing the dichotomy of being a modern woman.

Works Cited

Barton, Sue. University of California at Davis Health Journal. November 2000. 1 May 2006 hhttp://www.ucdmc.ucdavis.edu/healthjournal/ nov_dec_00_hj/articles/superwoman.html.i Baumgardner, Jennifer, and Amy Richards. Manifesta: Young Women, Feminism, and the Future. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2000. Bravo, Ellen. (9 to 5 Association). The Clerical Proletariat. Sisterhood is Forever: The Womens Anthology for a New Millennium. Ed. Robin Morgan. New York: Washington Square Press, 2003. 349 358. Chicago, Judy. Judy Chicago: through the Flower website. N.D. 1 May 2006 hhttp://www.judychicago.com/i. Chicago, Judy, and Edward Lucie-Smith. Women and Art: Contested Territory. New York: Watson-Guptill, 1999. Clement, Cari. Rwanda Knits Receives Grant. June 2005. 1 May 2006 hhttp://www.bond-america.com/whats_new/rwanda_june_05.htmli. Ditto, Beth. Livin Large: Beth Ditto from the Gossip is Big on DIY Fashion. BUST Feb./Mar. 2006: 38.

A Stitch in Time

699

Gillis, Stacy, Gillian Howie, and Rebecca Munford, eds. Third Wave Feminism: A Critical Exploration. New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2004. Graham, Sara. Craft Corner Book Watch: The Latest, Greatest DIY Reads. BUST Apr./May 2006: 104. Grosenick, Uta, ed. Women Artists in the 20th and 21st Century. Koln, Germany: Taschen, 2001. Hart, Jenny. Homepage. N.D. 1 May 2006 hhttp://www.sublimestitching. comi. Howell, Vicki. Homepage. N.D. 1 May 2006 hhttp://www.vickiehowell. com/made.htmli. Jackson, Julie. Personal interview. 12 Apr. 2006. . Homepage. N.D. 1 May 2006 hhttp://www.subversivecrossstitch. comi. Kelly-Landes, Jesse. Personal interview. 21 Mar. 2006. Lee, Whitney. Homepage. N.D. 1 May 2006 hhttp://www.madewith sweetlove.com/kits_frame.htmli. Lippard, Lucy. From the Center: Feminist Essays on Womens Art. New York: E. P. Dutton and Co. Inc., 1976. . The Pink Glass Swan: Selected Feminist Essays on Art. New York: The New Press, 1995. Lippard, Lucy, Edward Lucie-Smith, and Viki D. Thompson Wilder. Judy Chicago. New York: Watson-Guptill Publications, 2002. Max, Sarah. Master the Working-Mom Shufe: This Mothers Day Lose the Guilt and Look at the Bright Side of Balancing Kids and Career. CNN/Money. 8 May 2005. 1 May 2006. hhttp://money.cnn. com/2005/05/05/pf/workingmoms/index.htmi. McCombs, Emily. Sweater Living: Michelle Zacks Springs into Action with Spring and Clifton. BUST Oct./Nov. 2005. McGrath, Melanie. Somethings Wrong: Melanie McGrath on Tracey Emin. Tate Magazine Issue I. (Oct. 2002). 1 May 2006 hhttp:// www.tate.org.uk/magazine/issue1/something.htmi. National Museum of African Art Exhibition. Textures: Word and Symbol in Contemporary African Art. Exhibition accessed online at http:// www.nmafa.si.edu/exhibits/textures/artist-amer.html on 1 May 2006. National Museum of Women in the Arts Exhibition Catalog. Nordic Cool: Hot Women Designers, 2004. Pohjola, Ulla. Personal interview. 27 May 2004. Robinson, Hilary. Feminism-Art-Theory: An Anthology 1968 2000. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers Ltd., 2001. Rowe-Finkbeiner, Kristin. The F Word, Feminism in Jeopardy: Women, Politics, and the Future. Emeryville, CA: Seal Press, 2004.

700

Ricia A. Chansky

Sabella, Jennifer. Craftivism: Is Crafting the New Activism? Columbia Chronicle Online Edition. Summer 2006. 1 May 2006. hhttp:// columbiachronicle.comi. Showalter, Elaine, ed. The New Feminist Critic: Essays on Women, Literature, and Theory. New York: Pantheon Books, 1985. . Sisters Choice: Tradition and Change in American Womens Writing. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1994. Sider, Sandra. Miriam Schapiro: A Retrospective. Online at the Kristen Frederickson Contemporary Art Gallery, NY, 1 May 2006 hhttp://www.artcritical.com/sider/SSSchapiro.htmi. Sidler, Michelle. Living in McJobdom: Third Wave Feminism and Class Inequity. Third Wave Agenda: Being Feminist, Doing Feminist. Eds. Leslie Heywood and Jennifer Drake. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1997. 25 40. Stoller, Debbie. Stitch n Bitch: The Knitters Handbook. New York: Workman Publishing, 2003. . Stitch n Bitch Nation. New York: Workman Publishing, 2004. Stoller, Debbie, and Marcelle Karp, eds. The BUST Guide to the New Girl Order. New York: Penguin Putnam Inc., 1999. Stukin, Stacie. Pretty Crafty. Time Magazine 1 Mar. 2005. Traig, Jennifer. Crafty Girl Accessories: Things to Make and Do. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2002. Traig, Jennifer, and Julianne Balmain. Crafty Girl Cool Stuff: Things to Make and Do. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2001. What is Warm Up America! N.D. 1 May 2006 hhttp://www. warmupamerica.com/whatIsWUA.htmli. Wissinger, Joanna. Arts and Crafts Pottery and Ceramics. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 1994.

Ricia A. Chansky, PhD, is an assistant professor at the University of Puerto Rico at Mayagu where she teaches literature and writing. She is the coeditor of ez the scholarly journal a/b: Auto/Biography Studies. Her research interests include the literatures of marginalized communities, visual rhetoric as literary metaphor, Caribbean studies, autobiography studies, gender theory, interdisciplinary studies, visual culture, and alternate pedagogies. Recent publications include essays on the teaching of literature, feminist autobiography studies, and visual culture. She is currently working on an edited volume of pedagogical essays and a book about Shirley Jackson.

Copyright of Journal of Popular Culture is the property of Wiley-Blackwell and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

You might also like

- Fashion and Its Social Agendas: Class, Gender, and Identity in ClothingFrom EverandFashion and Its Social Agendas: Class, Gender, and Identity in ClothingRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (8)

- How Affect Feminist Art On Women Rights MovementDocument6 pagesHow Affect Feminist Art On Women Rights MovementAyşe TayfurNo ratings yet

- The Three Waves of Feminism: A Brief History of the Progressive Fight for Gender EqualityDocument4 pagesThe Three Waves of Feminism: A Brief History of the Progressive Fight for Gender EqualityIftikhar Ahmad RajwieNo ratings yet

- 2012 02 27 Threads Booklet SmallDocument52 pages2012 02 27 Threads Booklet SmallKaren Rosentreter VillarroelNo ratings yet

- Silvia Federici - Revolution at Point Zero - Housework, Reproduction, and Feminist Struggle (2012)Document201 pagesSilvia Federici - Revolution at Point Zero - Housework, Reproduction, and Feminist Struggle (2012)Adiba Qonita ZahrohNo ratings yet

- 4 Waves of Feminism by Martha RamptonDocument5 pages4 Waves of Feminism by Martha RamptonThoufiq KhaziNo ratings yet

- Women's Culture and Lesbian Feminist Activism - A Reconsideration of Cultural FeminismDocument31 pagesWomen's Culture and Lesbian Feminist Activism - A Reconsideration of Cultural FeminismAleksandar RadulovicNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10-Feminisms Matter-September 2020Document11 pagesChapter 10-Feminisms Matter-September 2020Jimsy JohnsonNo ratings yet

- Revolution at Point Zero: Housework, Reproduction, and Feminist StruggleFrom EverandRevolution at Point Zero: Housework, Reproduction, and Feminist StruggleRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (17)

- Second Wave FeminismDocument12 pagesSecond Wave Feminismwhats_a_nush0% (1)

- Research Paper Feminist ArtDocument5 pagesResearch Paper Feminist Artefh4m77n100% (1)

- A Study On Generational Attitudes Towards Female Nudity in ArtDocument20 pagesA Study On Generational Attitudes Towards Female Nudity in ArtmikasantiagoNo ratings yet

- The Confidential Clerk Vol.5 (2019)Document115 pagesThe Confidential Clerk Vol.5 (2019)The Confidential Clerk100% (1)

- Four Waves of Feminism ExplainedDocument6 pagesFour Waves of Feminism ExplainedXyril Ü LlanesNo ratings yet

- 4 Waves of FeminismDocument8 pages4 Waves of FeminismĐặng Kim TrúcNo ratings yet

- Nudity in Art: A Feminist PerspectiveDocument20 pagesNudity in Art: A Feminist PerspectiveMia SantiagoNo ratings yet

- Intellect Quarterly MagazineDocument16 pagesIntellect Quarterly MagazineIntellect Books100% (1)

- Makennacasadyart 1010 FeministartessayDocument6 pagesMakennacasadyart 1010 Feministartessayapi-306025416No ratings yet

- Modern Feminism in The USADocument11 pagesModern Feminism in The USAshajiahNo ratings yet

- Ilina Sen - A Space Within The Struggle. Women's Participation in People's MovementsDocument283 pagesIlina Sen - A Space Within The Struggle. Women's Participation in People's MovementsNiranjana Prasanna VenkateswaranNo ratings yet

- Download Feminist Afterlives Of The Witch Popular Culture Memory Activism Brydie Kosmina full chapterDocument67 pagesDownload Feminist Afterlives Of The Witch Popular Culture Memory Activism Brydie Kosmina full chapterjoann.baxley964100% (6)

- Stepping Out of The Third Wave: A Contemporary Black Feminist ParadigmDocument7 pagesStepping Out of The Third Wave: A Contemporary Black Feminist ParadigmVanessa Do CantoNo ratings yet

- FF 2 Ecfa 0 C 017073026 D 8Document6 pagesFF 2 Ecfa 0 C 017073026 D 8api-457791276No ratings yet

- Iar 6 PDFDocument32 pagesIar 6 PDFMary Murphy100% (1)

- Fashion and Sociology: Classical PerspectivesDocument7 pagesFashion and Sociology: Classical PerspectivesAnna BillegeNo ratings yet

- Feminsim TheoryDocument12 pagesFeminsim TheoryZea Monique Mag-asoNo ratings yet

- Making Feminism: Handcraft in Spare Rib MagazineDocument22 pagesMaking Feminism: Handcraft in Spare Rib MagazineRoberta PlantNo ratings yet

- FemminismDocument55 pagesFemminismPrabir DasNo ratings yet

- Feminine Identity and National Ethos in Indian Calendar ArtDocument8 pagesFeminine Identity and National Ethos in Indian Calendar ArtRandeep RanaNo ratings yet

- Hillary Belzer - Words + Guitar: The Riot GRRRL Movement and Third-Wave FeminismDocument121 pagesHillary Belzer - Words + Guitar: The Riot GRRRL Movement and Third-Wave FeminismRiOt GaaNo ratings yet

- Feminist Theory ScriptDocument7 pagesFeminist Theory ScriptRaymart ArtificioNo ratings yet

- Third Wave FeminismDocument21 pagesThird Wave FeminismKhalifa HamidNo ratings yet

- Multiracial FeminismDocument26 pagesMultiracial FeminismSimina ZavelcãNo ratings yet

- Resistance and MovementsDocument12 pagesResistance and Movementshexhero4No ratings yet

- Global Protest and Carnivals of ReclamationDocument9 pagesGlobal Protest and Carnivals of ReclamationHoracio EspinosaNo ratings yet

- Guerrilla Girls Invisible Sex in The Fie PDFDocument9 pagesGuerrilla Girls Invisible Sex in The Fie PDFAnelise VallsNo ratings yet

- Yanikdag (2023), Input On Feminist Media TheoryDocument13 pagesYanikdag (2023), Input On Feminist Media TheorycdyNo ratings yet

- Research Art Vs Discrimination FinalDocument7 pagesResearch Art Vs Discrimination Finalapi-612882296No ratings yet

- 1968 and The Paradox of Freedom PDFDocument12 pages1968 and The Paradox of Freedom PDFTitaNo ratings yet

- FeminismDocument23 pagesFeminismkennethNo ratings yet

- Sociology Project 3rd SemesterDocument27 pagesSociology Project 3rd SemestersahilNo ratings yet

- Contemporary ArtDocument6 pagesContemporary ArtEaston ClaryNo ratings yet

- Caliban and The WitchDocument242 pagesCaliban and The Witchsupsadups100% (12)

- Chapter - II Feminism - An OverviewDocument21 pagesChapter - II Feminism - An OverviewNimshim AwungshiNo ratings yet

- Georgiana VasileDocument27 pagesGeorgiana VasilePippaNo ratings yet

- Commoning with George Caffentzis and Silvia FedericiFrom EverandCommoning with George Caffentzis and Silvia FedericiCamille BarbagalloNo ratings yet

- Quilts For The Twenty First Century ActiDocument27 pagesQuilts For The Twenty First Century ActiKaren Rosentreter VillarroelNo ratings yet

- Dohrn-Jaffe The-Look-Is-YouDocument6 pagesDohrn-Jaffe The-Look-Is-Youapi-282608947No ratings yet

- Inside the Second Wave of Feminism: Boston Female Liberation, 1968-1972 An Account by ParticipantsFrom EverandInside the Second Wave of Feminism: Boston Female Liberation, 1968-1972 An Account by ParticipantsNo ratings yet

- Feminist MovementDocument11 pagesFeminist MovementRangothri Sreenivasa SubramanyamNo ratings yet

- Women's Rights Movement in IndiaDocument10 pagesWomen's Rights Movement in IndiaRogan RomeNo ratings yet

- Fashion's Role in the 1960s Women's Liberation MovementDocument4 pagesFashion's Role in the 1960s Women's Liberation MovementKelsey De JongNo ratings yet

- Feminist's ThereDocument14 pagesFeminist's ThereCaio Simões De AraújoNo ratings yet

- Feminism ReviewedDocument18 pagesFeminism ReviewedSehar AslamNo ratings yet

- Applying Feminism: Number 086 WWW - Curriculum-Press - Co.ukDocument4 pagesApplying Feminism: Number 086 WWW - Curriculum-Press - Co.ukChalloner MediaNo ratings yet

- Re-enchanting the World: Feminism and the Politics of the CommonsFrom EverandRe-enchanting the World: Feminism and the Politics of the CommonsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- October 2010 CatalogDocument32 pagesOctober 2010 CatalogstampendousNo ratings yet

- Novelty ArchitectureDocument5 pagesNovelty ArchitectureSharmistha Talukder KhastagirNo ratings yet

- HTR21 of Flexo Label Printing Machina 190522Document2 pagesHTR21 of Flexo Label Printing Machina 190522Gilbert KamanziNo ratings yet

- Artist and Artisan: Course HandoutsDocument6 pagesArtist and Artisan: Course HandoutsRenneth LagaNo ratings yet

- The Play That Goes WrongDocument39 pagesThe Play That Goes Wrongd artanjan83% (6)

- Regional Style ManduDocument7 pagesRegional Style Mandukkaur100No ratings yet

- KarateDocument15 pagesKarateFrank CastleNo ratings yet

- Beadwork Oct Nov 2013Document100 pagesBeadwork Oct Nov 2013sasygaby100% (18)

- Zaha Hadid Inspiration From MalevichDocument9 pagesZaha Hadid Inspiration From Malevichedgard jeremyNo ratings yet

- STOCK AVAILABILITYDocument1 pageSTOCK AVAILABILITYNova ImperialNo ratings yet

- Table linens and dinnerware vocabularyDocument2 pagesTable linens and dinnerware vocabularyElenNo ratings yet

- CNU II 12 Piano and Organ Works PDFDocument352 pagesCNU II 12 Piano and Organ Works PDFWUNo ratings yet

- This Masquerade DMDocument1 pageThis Masquerade DMPieter-Jan Blomme100% (2)

- Destroy This Mad Brute Vs VogueDocument2 pagesDestroy This Mad Brute Vs VogueMia CasasNo ratings yet

- 1 Point Perspective GridDocument8 pages1 Point Perspective GridRohan BhardwajNo ratings yet

- Inside Arabic Music f390Document481 pagesInside Arabic Music f390Patrick Stewart100% (16)

- Creative ImagesDocument28 pagesCreative ImagesFabio Nagual100% (2)

- The Medusa PlotDocument391 pagesThe Medusa PlotDíniceNo ratings yet

- Post-war Poetry of Philip Larkin and The MovementDocument7 pagesPost-war Poetry of Philip Larkin and The MovementBarbara MazurekNo ratings yet

- GAMABA WeaverDocument7 pagesGAMABA WeaverDavid EnriquezNo ratings yet

- 6 8 Year Old Lesson PlanDocument4 pages6 8 Year Old Lesson Planapi-234949588No ratings yet

- 25 My LunchDocument11 pages25 My Lunch周正雄100% (1)

- Tese Beatbox - Florida PDFDocument110 pagesTese Beatbox - Florida PDFSaraSilvaNo ratings yet

- Boys & Girls School Vest Knitting PatternDocument3 pagesBoys & Girls School Vest Knitting PatternOver LoadNo ratings yet

- Town Planning PDFDocument22 pagesTown Planning PDFMansi Awatramani100% (1)

- Requiem in D MinorDocument81 pagesRequiem in D MinorAmparo BaltazarNo ratings yet

- Slidw Group 009 Yarn Structure AnalysisDocument59 pagesSlidw Group 009 Yarn Structure AnalysisAliAhmadNo ratings yet

- Review Method For ChildrenDocument12 pagesReview Method For ChildrenVictor HamiltonNo ratings yet

- Steel Doors and Windows For 2013-14Document59 pagesSteel Doors and Windows For 2013-14Senthil KumarNo ratings yet

- D& D5e - (Midnight Tower) - A Most Unexpected Zombie InvasionDocument13 pagesD& D5e - (Midnight Tower) - A Most Unexpected Zombie InvasionDizetSmaNo ratings yet