Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Brief History of Management Accounting

Uploaded by

Gkæ E. GaleakelweOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Brief History of Management Accounting

Uploaded by

Gkæ E. GaleakelweCopyright:

Available Formats

The History of Management Accounting

By Osmond Vitez, eHow Contributor updated: July 28, 2010

I want to do this!Management accounting is an internal business function that focuses on the

recording and reporting of internal financial information. This process commonly provides information for business decisions. Though it is an important business function, management accounting is not as old as financial accounting.

Origins

1. According to the Accounting for Management website, management accounting dates to the Industrial Revolution of the 19th century. Many companies during this time were owned by individuals rather than shareholders. Owners needed financial information particular to their operations rather than statements for external users.

Features

2. Management accounting information was primarily for internal use. Owners and managers relied on information about their company's production process for making decisions and measuring performance.

Growth in the business environment increased the need for financial accounting information released for external business stakeholders, according to the Accounting for Management website.

Currently

3. Management accounting is a common business function in today's business environment. Companies use a mixture of management and financial accounting for their financial processes. Because management accounting does not require the use of standard accounting principles, owners and managers have some latitude in preparing this information. Accounting Courses + MBAwww.LSBF.org.uk/ACCA Get MBA or MSc Fully Sponsored with ACCA/CIMA Course, Apply Now! Finance&Accounting MasterStudyInterActive.org/MSc-Finance Top British MSc Degree, 100% Online Course, 24/7 Access,Apply in Jan'10 Find the Ideal Speakerwww.SpeakersAssociates.com For any event - conferences, after dinners - we can help!

Study ACCA,Get MBA Fundedwww.CA-MBA.com/ACCA

Read more: The History of Management Accounting | eHow.com http://www.ehow.com/facts_6786237_history-managementaccounting.html#ixzz14LBeXuW5

MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTING CONCEPTS AND TECHNIQUES

By Dennis Caplan, University at Albany (State University of New York)

CHAPTER 2: Relevant Concepts from the Fields of Strategy and Operations Management, and a Brief History of Management Accounting

This chapter describes some concepts and characteristics from the fields of strategy and operations management that are relevant to the study of management accounting. Because management accounting is a management support function, management accountants need to be aware of emerging trends, issues and techniques in the field of management. Also, because many of the most challenging management accounting problems occur in the manufacturing sector of the economy, management accountants must have a solid understanding of the terminology

and basic characteristics of common manufacturing processes. This chapter also provides a brief history of the development of management accounting.

Manufacturing Processes:

Manufacturing industries can be categorized according to the extent to which individual units of output are distinguishable from each other during and subsequent to the production process. We describe four points on a continuum. Job order: In a job order process, each unit of output is unique. Examples include a custom home builder and a custom furnituremaker. Batch process: In a batch process, identical (or very similar) units of output are produced in groups called batches, but the units in one batch can differ significantly from the units in another batch. The units within each batch usually remain within close physical proximity throughout the production process. Apparel factories often use a batch process. For example, different styles of pants are produced in separate batches. Each batch might consist of 50 or several hundred pairs of pants. Within each batch, there might be minor differences, such as different waist and inseam sizes. At any one time, the factory might have work-in-process related to several different styles of pants, and numerous batches of work-in-process for each style. Assembly line: In an assemblyline process, similar units are produced in sequence, usually in a

highly-automated operation. The automobile industry is a good example. An automobile manufacturer makes only one model car on any one assembly line. The assembly line allows for some product differentiation. For example, cars produced on the assembly line can differ from each other with respect to such features as color and upholstery, and perhaps in more substantive ways such as the size of engine, and two-wheel versus all-wheel drive. However, to change an assembly line from one model to another usually requires significant expense and down-time. Continuous process: In a continuous manufacturing environment, the manufacturing facility produces a continuous flow of product during the operating hours of the facility. A classic example of a continuous process is an oil drilling operation. The distinguishing feature of a continuous process is that any grouping of output into individual units is arbitrary. For example, oil can be divided into barrels or gallons or any other measure of liquid volume. In order to determine the cost of production in a continuous process, it is necessary to select a period of time, collect costs incurred during that period, determine the amount of output produced during that same period, and divide total costs by total output. There is no presumption that a continuous manufacturing process is a one-product facility (drilling operations often extract both crude oil and natural gas), or that it runs 24 hours a day.

Overview of manufacturing processes: Distinguishing manufacturing processes along this continuum is helpful, because where a process falls on this continuum influences the types of management accounting issues that arise, and the design of the management accounting system. However, it is often difficult and seldom helpful to classify any particular manufacturing process precisely into one of the four points of the continuum described here. Also, any one company might operate over several points on this continuum.

Decentralization:

An important issue in the management of firms is the extent to which decision-making is centralized or decentralized. Many large companies operate in a highly decentralized fashion, and have numerous responsibility centers and responsibility-center managers with considerable autonomy. Important types of responsibility centers include the following: Cost centers: Managers of cost centers are responsible for costs only. Most factories are cost centers. Profit centers: Managers of profit centers are responsible for revenues and costs. The Jeans Division of Levi Strauss & Co. might be a profit center. Investment centers: Managers of investment centers are responsible for revenues, expenses, and invested capital. The Canadian Division of Levi Strauss & Co. might be an investment center.

Following are important benefits of decentralization. 1. Decision-making is delegated to managers who are often in the best position to understand the local economy, consumer tastes, and labor market. Autonomy is inherently rewarding. Job positions that are characterized by a high degree of responsibility and autonomy are likely to attract and retain more talented, experienced and capable managers than positions that provide managers minimal decision-making authority. Companies that delegate responsibility deep within the organization create a training ground where managers gain experience and prepare themselves for higher-level positions. Decentralization places fewer burdens on top management. Highlycentralized companies impose on top management the responsibility for numerous routine decisions.

2.

3.

4.

Following are important costs and risks of decentralization. 1. The incentives of responsibility-center managers do not always align with the incentives of owners or top management. There is the obvious risk

that managers might consume perquisites at the expense of corporate profits (e.g., expensive business lunches and office furniture). Also, there is evidence that managers will attempt to increase the size of the units for which they are responsible (called the managers span of control), even if doing so does not increase the profitability of the company. 2. Economic theory suggests that managers prefer for the responsibility center under their control to accept less risk than owners would like. This theory builds on the observation that higherrisk projects generate higher returns, on average, reflecting the trade-off between risk and return, which constitutes a building block of finance theory. Shareholders prefer riskier projects than managers, because shareholders can diversify their portfolios by owning shares in numerous companies. However, the managers career is closely connected with the performance of his or her responsibility center. Consequently, managers of responsibility centers of decentralized companies might reject risky projects that shareholders would favor.

Although there are both benefits and costs to decentralization, it would appear that by any objective

measure, most large corporations operate in a highly-decentralized fashion. As a benchmark, one might wish to compare the extent of decentralization in modern corporations with the extent of decentralization in such entities as the military or the former Soviet economy.

The Origins of Management Accounting:

Management accounting first emerged as a significant activity during the early industrial revolution, in the leading industries and enterprises of the day. As such, management accounting arose after financial accounting, which can trace its origins to its stewardship role in European merchant trading ventures beginning in the Italian Renaissance, and to tax records that governments apparently have required for as long as governments have existed. Doubleentry bookkeeping had been used for more than 300 years by the time management accounting first emerged as a recognizable field. Two leading industries of the industrial revolution that played important roles in the early history of management accounting were textiles and railroads. Textile mills used raw materials and labor to make fabrics and associated products, and the mills developed methods to track the efficiency with which they used these inputs. Railroads required significant investments of capital over long periods of time for the construction of roadbed and track. Once operational, railroads handled large volumes of cash receipts from numerous customers, and developed both financial and operational measures of efficiency for moving passengers and freight. By the end of the 19th century, new industries and types of businesses were becoming important to the economies of the United States, Great Britain, and other industrializing nations. These enterprises included steel

producers, mass producers of consumer products such as foodstuffs and tobacco, and mass merchandisers such as Sears, Roebuck & Company. Leading companies in these industries developed accounting systems to meet their needs for operational control. In the first two decades of the 20th century, the fields of industrial engineering and management accounting developed in tandem. During this period, industrial engineers developed methods to control production that included a scientific determination of standards for inputs of materials, labor and machine time, against which actual results could be compared. This development led directly to standard costing systems, which are still widely used by manufacturing companies. Management accounting concepts and techniques continued to evolve rapidly throughout the rest of the first half of the 20th century, and by 1950 most of the key elements of management accounting as practiced today were well established. These developments occurred in a decentralized fashion, inside large companies that were using common sense and commonplace bookkeeping and analytical tools to meet their internal reporting requirements. Companies that business historians have identified as innovators in management accounting practice during this period include DuPont, General Motors and General Electric. However, an innovator is not necessarily a leader. There appears to have been relatively little communication among companies

regarding the management accounting methods that were developed. Perhaps managers and accountants viewed these accounting systems and techniques as proprietary, a possible source of competitive advantage. Also, there was no institutional or regulatory impetus for sharing information. In the early 1900s, there was no association of management accountants to hold annual meetings in Chicago or Boston for continuing professional education and revelry. There was no government oversight of management accounting practice. With very few exceptions, management accounting itself was not required for regulatory purposes until the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act of 1977, which mandated that large companies maintain adequate systems of internal control. Even today, companies have a great deal of discretion in the design of management accounting systems, and management accounting looks very different from one company to another even within the same industry.

Key Developments in the Past 50 Years:

The economic, business and technological developments that have probably had the greatest impact on management accounting over the last 50 years are the following: The information revolution: Those of us born in the second half of the 20th century have difficulty appreciating the enormous hurdle that the collection and processing of information once posed to management accounting systems,

and the impact that the cost of information had on management in general. Today, information technology makes possible sophisticated database accounting systems that are both powerful and flexible in terms of the accounting information that they can collect, organize and report. Even today, however, the cost of designing, implementing, and running cost accounting systems is a substantial obstacle in many organizations; a fact probably underrepresented in business schools. Proliferation of product lines: If a company makes only one product, many cost accounting issues are moot. When companies significantly expanded their product lines beginning in the 1950s, to gain market share and increase profits, the difficulty and importance of obtaining accurate cost information on individual products increased. It is generally agreed that in the 1970s and 1980s, some U.S. companies were allocating costs among products in a manner that led to poor production and marketing decisions. A management accounting tool called activitybased costing was developed to help correct this problem, by improving the accuracy with which costs are allocated among products. Globalization of the economy: Globalization has several implications for management accounting. First, globalization has resulted in a more competitive environment, which encourages the implementation of accounting systems that provide the most accurate, relevant, and timely information possible. Second, the

growth of multinational corporations has increased the importance of transfer pricing. A transfer price is the amount one division of a company charges another division for an intermediate product. Transfer pricing plays a role in taxation, international trade negotiations, and production and marketing decisions within decentralized firms. Finally, globalization has increased the pace of change within the management accounting profession. Many recent innovations in management accounting, as well as in the fields of strategy and operations management, originated in Japan. Direct competition between Japanese and U.S. companies has led many U.S. companies to adopt these Japanese management practices. Increasing importance of the service sector: Prior to the 1970s, most innovations in management accounting techniques, and the most sophisticated management accounting systems, were found in manufacturing firms (although as discussed above, railroads played an important role in the early development of management accounting). As the service sector became a larger part of the overall economy, and as competitive pressures within service sector industries increased (in some cases brought about by deregulation), many service companies invested substantial resources in management accounting systems tailored to meet their needs. Service sector industries noted for significant developments in their management accounting systems include transportation, financial institutions, and health care.

Customer costing (determining the cost of servicing an individual customer), and improving the timeliness of accounting information, are two issues of particular importance to many service sector companies.

Innovative Management Practices:

In addition to the four economic and technological trends described above, the following innovations in the fields of strategy and operations management have influenced management accounting systems and practices over the past several decades. Total quality management (TQM): Quality programs go by several names, including TQM, zero defect programs, and six sigma programs. The focus on quality has had a significant impact on many organizations in all sectors of the economy, beginning with the automobile industry and some other industries in the manufacturing sector of the economy about forty years ago. Sophisticated quality programs are found today in many areas of government, education and other not-for-profit organizations as well as in for-profit businesses. The impetus for TQM programs is the assessment that the cost of defects is greater than the cost of implementing the TQM program. Advocates of TQM claim that some costs of defects have been underestimated historically, particularly the loss of customer goodwill and future sales when a defective unit is sold. Some advocates of quality programs believe that the most cost-effective

approach to quality is to eliminate all defects at the point at which they occur. If successful, these zero defect programs would not only result in higher levels of customer satisfaction, but would also eliminate costs associated with more conventional quality control procedures, such as inspection costs that occur at the end of the production line, the cost of reworking units identified as defective, and costs associated with processing customer returns. The focus is on preventive controls to prevent the defect from occurring in the first place, as opposed to detective controls to identify and correct the defect after it has occurred. Just-in-time (JIT): During the last two decades of the 20th century, many companies implemented just-in-time programs designed to minimize the amount of inventory on hand. These companies identified significant benefits from reducing all types of inventories raw materials, work-in-process, and finished goodsto the lowest possible levels. These benefits consist principally of reduced inventory holding costs (such as financing and warehousing costs), reduced losses due to inventory obsolescence, and more effective quality control. The relationship between JIT and TQM is important. Many defects in raw materials or the production process can be ignored indefinitely if high-quality materials can be substituted for defective materials, and if additional first-quality units can be produced to replace defective units. In a non-JIT environment, defective materials and half-finished units might be set

aside in a corner of the factory. However, under a JIT program, if raw materials received at the factory are defective, there might be no first-quality materials on hand to substitute for the defective materials. In extreme cases, the production line might be shut down until first-quality materials are received. Hence, a JIT program can focus attention on quality control in ways not generally possible in a non-JIT environment. The challenge in a JIT environment is to avoid stock-outs. To meet this challenge, some companies have found ways to decrease production lead times. Shorter production schedules result in less work-in-process inventory, and also allows companies to maintain lower levels of finished goods inventory while still maintaining high levels of customer satisfaction. Early in the 21st century, acts of terrorism (such as the destruction of the World Trade Center in New York City) and natural disasters (such as Hurricane Katrina) prompted some companies to rethink the practice of maintaining extremely low levels of inventories. These companies are concerned that future incidents could result in the disruption of inventory pipelines, particularly for imported materials. Consequently, the advantage of maintaining safety stocks of inventory is receiving renewed interest. Theory of constraints: The theory of constraints is an operations management technique that decreases inventory levels and increase throughput in a

manufacturing setting. Eliyahu Goldratt, a business consultant, is largely responsible for the development of the theory of constraints. Goldratt popularized his ideas in a business novel that he coauthored with Jeff Cox called The Goal: A Process of Ongoing Improvement. The basis of the theory is to identify bottlenecks in the production process, and to focus all efforts on increasing the capacity of the bottleneck operations. Typically, bottleneck operations are easy to identify, because large amounts of inventory back up at these operations waiting to be processed. The theory of constraints also advocates setting the speed of the entire production process at the speed of the bottleneck operation, because otherwise excess work-inprocess will inevitably build up. This pull system should replace traditional push systems, where every operation processes inventory at its maximum capacity. Like most new ideas, the theory of constraints has a basis in earlier techniques and ideas. As early as the 1970s or 1980s, engineers and production managers used a tool called critical path analysis to predict the time required to accomplish major new objectives, such as introducing a new product or bringing a new facility on line. Critical path analysis involved identifying the sequence in which various steps were required, and identifying at what point, and for how long, the entire project would depend on the completion of any particular step. Lean production and the lean enterprise: In recent years, the term lean has been adopted by

some organizations to describe the organizations comprehensive effort to apply state-of-the-art management practices to improve quality and customer satisfaction, reduce costs and production leadtimes, and increase value-creation. Lean is an umbrella term that includes such techniques as JIT and TQM as component elements. Some accountants credit Toyota as the originator of lean production. The term lean was originally applied to manufacturing settings, such as in the phrases lean production or lean manufacturing. But the term is now used more broadly, and sometimes describes lean initiatives in the distribution and support functions of a manufacturing company, lean initiatives in service-sector companies, and even initiatives in other types of organizations such as governmental entities. The term lean accounting has been coined to describe accounting systems that either support lean production, or that are, themselves, lean.

July 1999 Issue The CPA Journal Millennium Series

The Accounting Profession in the 20th Century

By Wallace E. Olson The second in a series of articles commemorating the past, present, and future of the CPA profession, from a variety of perspectives, as it approaches the new millennium.

In Brief

Preparing for the 21st Century The accounting profession in this country was built upon a state-established monopoly for audits of financial statements. The Federal securities statutes of 1933 and 1934 raised the stakes to the

national level and caused the rapid growth of firms that audit public companies. They also had the effect of dividing the profession between those firms that audit public companies and those that do not. In the 1970s, demands for more reliable and comparable financial reporting by Congress and the SEC led to the transfer of accounting principles standards setting to FASB. At about the same time, the plaintiff's bar discovered the profession's deep pockets and started to pursue the large firms, aggressively seeking sizable damage awards. A series of spectacular business failures and the actions of big oil companies led Congress to question the performance of the SEC and the accounting profession. The result was the establishment of the AICPA Division for CPA Firms, which, while responding to perceived structural weaknesses, also served to further separate firms that do SEC audits from those that do not. On top of this, the repeal of anticompetitive rules against advertising and solicitation of clients, under pressure from the Federal Trade Commission, caused even more turmoil in the '70s. Increased competition, with its pressures on pricing, led the large firms to seek out other services to offer, which led to the growth in consulting practices. This has provoked the SEC and others to question the effect on auditor independence that the huge fees paid by audit clients for consulting services may have. The author, president of the AICPA during the decade when many of these events took place, looks to the future and where the profession is headed. He suggests it may be time for a high-level commission to take a hard look at the structure and direction of the profession. It has long been held a truism that those who ignore history are doomed to repeat the mistakes of the past. With this in mind, it would seem appropriate at the end of the 20th century to retrace the development of the public accounting profession in the United States to see what guidance the past may offer to the future. The American profession was, for the most part, founded by accountants that migrated from England and Scotland in the 19th century. It emerged over many decades into the organizational structure that is today the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants. Two books authored by John L. Carey, who served as staff head of the AICPA from 1930 to 1967, give a full account of the events and efforts that resulted in firmly establishing public and political recognition of the profession during the first 70 years of the century. It is noteworthy that most of the founders' early attention was directed toward persuading state legislatures to enact laws providing for the examination and certification of public accountants and restricting the performance of opinion audits to those that successfully passed the examination and became certified. The result was the establishment of a state-based monopoly fundamental to assuring accountancy's status as a recognized profession. The American state-based approach to regulation of the profession was supplemented in the 1930s with the passage of the Federal securities acts giving birth to the Securities and Exchange Commission. The SEC was established to deal with the problems that caused the 1929 crash and the ensuing economic depression. The SEC was empowered, among other things, to require independent audits of companies, which had to register with the SEC before selling their securities to the public. The profession successfully persuaded Congress and the newly established SEC to rely on the AICPA to set accounting and auditing standards for the purposes of filing financial reports with the SEC. However, the SEC retained the authority to override those standards when it deemed necessary. In addition, the SEC has the authority to disbar CPAs from SEC practice when, in its judgment, they fail to meet their responsibilities under its rules. The SEC's Impact

The establishment of this new form of Federal regulation of the securities markets strongly influenced the development of the public accounting profession. Among other things, it gave impetus to the rapid growth of firms auditing SEC registrants, which culminated in the large national and global firms that exist today. Because virtually all SEC registrants were clients of a small number of CPA firms, the distinctions between public accounting practice on a local and regional basis and that of the SEC practice firms were destined to result in a serious divide within the ranks of the profession. The distinctions were further exacerbated by the rapid growth of the national firms through a large number of acquisitions of local and regional firms from the 1950s through the 1970s. Demands by the SEC and Congress for more reliable and comparable financial reporting put increasing pressure on the profession to establish more comprehensive and refined accounting and reporting standards. This effort was originally carried out under the AICPA through a series of modified organizational structures largely dominated by representatives of SEC practice firms. Ultimately, as a result of widespread criticism by groups having a stake in the financial reporting process, the standards-setting function was transferred in 1973 to the present Financial Accounting Standards Board under control of the Financial Accounting Foundation. This independent body, however, is subject to pressures from the conflicting interests of its constituent groups as well as the SEC and Congress. The growing body of complex standards to deal with increasingly sophisticated forms of business transactions and financial instruments has resulted in standards overload. Accounting theorists insist that standards should apply to SEC registrants and nonregistrants alike. In the world of local firm practice, however, this is seen as an unrealistic and unnecessary burden on accountants, their clients, and the users of their financial statements. This difference in viewpoint has aggravated the divide between firms serving nonSEC clients and large firms practicing under the watchful eye of the SEC and Congress. The visibility of the large CPA firms and the AICPA grew dramatically during the 1970s. The financial press began reporting extensively on their activities, especially in connection with large business failures that raised questions about the performance of auditors. These events also attracted the attention of the plaintiff's bar, which brought huge class-action suits against the large CPA firms. The exposure to this risk had several effects: * The skyrocketing cost of liability insurance premiums and increase in deductibles posed a serious threat to the survival of individual firms. * The firms tightened their internal policies and their audit procedures to minimize liability risk. * The firms lost some of their enthusiasm for the audit side of their practices and began placing more emphasis on consulting services, which were both financially rewarding and less prone to litigation. This trend was made more acute by the loss of large company audits stemming from the rash of mergers and acquisitions during the last three decades of the century. Who's to Blame? During the 1970s, scandals involving illegal payments and bribes by companies with foreign operations, a series of spectacular and unheralded business failures, and huge increases in oil prices generated a high level of interest by Congress in the adequacy of the performance of the SEC and the accounting profession. What followed was an intensive look at the profession by two congressional subcommittees that held public hearings and issued reports on their findings and recommendations. It is noteworthy that the congressional concerns were focused almost entirely on the profession's practice under the SEC's jurisdiction and had virtually nothing to do with the performance of local and regional firms. Each of the large firms testified at the hearings on its own behalf, expressing views that did not present a united front. Indeed, on some matters they directly contradicted each other. The AICPA

testified on behalf of the entire profession and formulated a program of changes that responded to the perceived shortcomings expressed during the course of the hearings. It became apparent that AICPA membership structure, by individuals rather than firms, added to difficulty dealing with the problems of the profession. While the individual members of the AICPA seemed to aspire to equal status as CPAs, those practitioners not subject to Federal regulation were generally not too keen about being saddled with the extra burdens and responsibilities imposed on the large SEC practice firms. In 1978, the AICPA attempted to cope with this less than satisfactory situation by establishing a Division for CPA Firms with two sections, one for firms serving private companies and one for firms serving or aspiring to serve SEC registrants. It was hoped that through this organizational structure the nonSEC practice firms could be spared the more stringent requirements imposed on SEC practice firms. Key features of the SEC Practice Section are required peer reviews, mandatory continuing education, reporting on liability lawsuits, and monitoring of the section's activities by a Public Oversight Board composed of prominent individuals mostly from outside the accounting profession. Repeal of Anticompetitive Rules During the 1970s, the U.S. Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission embarked upon a program to force professional organizations to repeal their rules banning advertising, solicitation, and competitive bidding. The AICPA became an early target and, on the advice of its legal counsel, signed a consent decree to repeal its rules of conduct that were deemed anticompetitive. Before the repeal of the AICPA's rules, the largest firms were at least indirectly soliciting clients and offering to perform services at the same fees others had charged the prior year. However, they refrained from openly advertising in order to acquire business. Generally, the small firms complied with the prohibitions, believing it would be injurious to the profession's reputation if they violated the spirit of the rules. With the repeal of the rules, the level of competition within the profession increased dramatically, putting heavy pressure on fees charged. This in turn put a premium on performing services as efficiently as possible, which may have had a negative effect on the quality of work performed. In any event, the forced repeal of the rules regarded as anticompetitive under the Sherman Antitrust Act may have temporarily reduced the costs to consumers of the profession's services. If so, lower costs were achieved at the risk of diminishing the quality of opinion audits. The playing field for engaging in advertising was not level, because the large firms could devote far greater resources to this activity than the smaller firms. This disadvantage may have been somewhat reduced by the institutional advertising program sponsored by the AICPA and state CPA societies. Over time, the profession seems to have adapted to a new world where all-out competition with other CPAs as well as non-CPA groups is accepted as a way of practice. Consulting Practice One of the most important developments since the 1970s has been the greater emphasis on providing consulting services in a wide range of business management areas, which requires competence in a variety of established disciplines that lie outside the traditional training and skills of a CPA. Historically, CPAs have acted as consultants to their accounting, auditing, and tax clients, but consulting fees constituted a minor portion of their total practice. The services offered were generally closely related to accounting and taxes. Today, however, consulting is the largest source of income for the largest CPA firms, and the types of services are broader and rendered on a far more formal and sophisticated level than in the past. The larger CPA firms actively compete at the level of the biggest non-CPA consulting firms. This phenomenon is generally not true of the thousands of small local CPA firms that do not have the resources to provide formal consulting in the same depth and breadth as the large national firms. However, some local and regional firms do specialize and are recognized as experts in a single field

such as real estate development, health care, or litigation consulting. The use of professional accreditations and specialty designations provides a way to affirm that a CPA is suited for a particular engagement. Underlying the concept of auditor independence is the need to retain an outsider status to the maximum extent possible. Clearly, consulting services performed for an audit client work contrary to this objective because they require the auditing firm to become more deeply involved in the affairs of the client. Consulting and Independence The term "consultant" lacks a clear focus because it embraces a diversity of specialties from a variety of professional groups. In short, a consulting firm is generally by necessity an amalgam of professions operating under a single identity. This is important because it poses the question, addressed repeatedly during the past 30 years, of whether an auditing practice can retain its objectivity in appearance and in fact when it is combined with a consulting practice under a single firm or a commonly owned consulting firm. Congressional subcommittee hearings in the 1970s and periodically since then have raised concerns about combining the independent audit function with the practice of consulting. Their concerns resulted in the voluntary ban by the SEC Practice Section firms of certain types of consulting engagements and required disclosures about others. One firm, Arthur Andersen, decided to transfer its consulting practice to a separate, but commonly owned, entity in response to independence concerns. According to newspaper accounts, this approach has led to internal turmoil and strife between the separate entities. This result was probably inevitable because the mindset and objective of auditors are different from those of consultants. Based upon the Arthur Andersen experience, it seems clear that practicing auditing and consulting under commonly owned entities is fraught with internal problems. These same problems also exist where the two practices are combined under a single firm entity; however, they may be less acute and less visible under one management. Regardless of internal friction, the question of whether consulting poses an unacceptable threat to the objectivity of a firm's audits remains unresolved. The AICPA and others have argued that consulting enhances the quality of audits because it provides more insight into a company's operations. In theory, this results in more informed judgments about the validity of management's representations. This may be more theory than fact, because it assumes excellent and unbiased communication between consultants and auditors. Another argument for consulting is that the glamour it exudes helps firms recruit the upper level of accounting graduates to their audit staffs. Presumably, members of the audit staff will then go on to the more exciting consulting work. In actuality, this has been the exception rather than the rule because the consulting staff has been largely recruited from among those with education and experience in other disciplines. Even if these are valid considerations they must be weighed against the effect on independence when the services are provided to audit clients. It has been argued that the audit fee itself is a much bigger threat to independence. While this may be true, it does not follow that the added threat posed by consulting is inconsequential. Neither does it help to say that an internal wall between consultants and auditors mitigates the threat. To do so is in direct contradiction to the assertion that consulting enhances the quality of audits by providing a deeper understanding of the client's company. The SEC's concerns that the credibility of the audit function was eroding in the midst of large consulting practices led to the establishment of the Independence Standards Board to deal with matters relating to the independence of auditors practicing before the SEC. Most of the board members are not members of the CPA profession. This action can be construed as a vote of no confidence in the profession's ability to adequately enforce its own independence rules.

In addition, if control of Congress should shift to the present minority party in 2000, an investigation and public hearings could become a strong possibility. This would almost certainly be triggered if there is a sharp downturn in the securities markets or the economy or both, causing a number of major business failures. At the end of the century, the Big Five firms, which audit the bulk of SEC registrants, have become huge global businesses. If their emphasis on consulting continues, as their advertising suggests, then their image as independent auditors will no doubt become increasingly diluted. Congress might conclude that mixing consulting with auditing is no longer an acceptable practice. Less extreme and more likely, each firm would be prohibited from providing consulting services to its audit clients. This course of action would likely cause a reshuffling of consulting clients among the firms without an overall reduction in business. Standards Setting If, as discussed above, Congress is stimulated by future events to take another close look at the profession it will almost certainly examine the present arrangement of financial accounting and reporting standards setting utilized by FASB. While FASB and the profession might find such scrutiny uncomfortable, it seems unlikely that changes would result. But there is no guarantee that Congress would not direct the SEC to rescind its delegation to the present structure and either set the standards itself or, less likely, delegate standards setting to some other governmental body such as the Governmental Accounting Office. Given the unpredictability of the political process, almost anything could happen if the profession were to fall into serious disfavor with the SEC or Congress. But one thing seems certain: The issue of standards setting and the effects of consulting on the independence of auditors would head the list of matters to be reexamined. The NonSEC Client Firms More than 40,000 CPA practice firms do not fall under the requirements of the SEC because they do not audit SEC registrants. But some of what the profession does to meet the requirements of the SEC affects them in the form of peer reviews and complex accounting and financial reporting standards. Efforts have been made to provide a degree of relief, but some firms have resisted being granted exemptions. They fear being viewed as second-class and subsequently losing their larger clients to the big firms. The problem of standards overload in smaller firms has festered for many years and ought to be resolved. A solution may lie in the fact that the SEC has size criteria, which, if not met, exempt companies from its purview. Presumably, below a certain company size Congress and the SEC are content to let minority shareholders and credit grantors fend for themselves. Perhaps a similar de minimus theory ought to be applied to privately owned companies where credit grantors have ample leverage to obtain the information needed for their decision-making. Consolidators and Alternative Practice Structures A recent development is the arrival of consolidators and alternative practice structures. Large commercial organizations have concluded that providing CPA-type services to middle-market businesses can be profitable as an end to itself and as a cross-seller to other business segments. Because of state regulatory restraints, the large consolidators have had to develop a rather convoluted way of providing audit and other attest services: A shell partnership provides the audit report using employees leased from the consolidator. Independence questions have been raised by the SEC for the handful of SEC clients that acquired CPA firms continue to serve. With the talk of HRB Business Services, a subsidiary of H&R Block, acquiring McGladrey & Pullen, however, this could become more of a problem. Many Problems Remain Unsolved

This thumbnail account of the history of the profession in the 20th century is by no means comprehensive. However, it is sufficient to draw the conclusion that many problems remain unsolved and that circumstances are not likely to be static for any great length of time in the 21st century. It is difficult to predict what new challenges may arise in the next 20 years, but a look at recent history may provide clues. For this reason, and because solutions are needed to problems already identified, the profession through the auspices of the AICPA ought to appoint a high-level commission to take a hard look at whether the present structures and direction of the profession are appropriate for the new century. Such a commission ought to seek the views of representatives from all groups that have a stake in the work product of the profession in its current structure and scope of services. The goal should not be how things can be kept the same or how the capacity for services can be increased. Rather, the goal should be reaching an objective conclusion about how the profession can best meet the needs of society in the days ahead and what structural changes may be needed to achieve this result. The profession will survive and flourish if it is driven by a desire to serve society to the best of its ability and not simply to make money for its own benefit. In the final analysis, this is the hallmark of any great profession. *

Wallace E. Olson, CPA, served as chief staff officer of the AICPA from 1972 to 1980. He had been associated with Alexander Grant & Company (now Grant Thornton) for more than 25 years and became its executive partner in 1967. He served on the Wheat Committee from 1970 to 1972, which ultimately led to the formation of the Financial Accounting Standards Board. His book, The Accounting Profession: Years of Trial 19691980, was published by the AICPA in 1982.

You might also like

- Management Accounting: Retrospect and ProspectFrom EverandManagement Accounting: Retrospect and ProspectRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (5)

- Accountd TRIM III ProjectDocument11 pagesAccountd TRIM III ProjectcooL_ISHHHHHNo ratings yet

- Profit CentersDocument22 pagesProfit CentersRaj GuptaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 21Document13 pagesChapter 21maheshNo ratings yet

- P1 Course NotesDocument213 pagesP1 Course NotesJohn Sue Han100% (2)

- Mba 507: Management Accounting: Revised Edition 2013 Published by Kenya Methodist University P.O. BOX 267 - 60200, MERUDocument73 pagesMba 507: Management Accounting: Revised Edition 2013 Published by Kenya Methodist University P.O. BOX 267 - 60200, MERUMarkmarie GaileNo ratings yet

- Ch18.Outline ShareDocument9 pagesCh18.Outline ShareCahyo PriyatnoNo ratings yet

- MANAGERIAL ACCOUNTING INSTRUCTIONAL MATERIAL Chapter 2Document9 pagesMANAGERIAL ACCOUNTING INSTRUCTIONAL MATERIAL Chapter 2Shyra OnacinNo ratings yet

- RMK 3 Divisional Financial Performance MeasuresDocument7 pagesRMK 3 Divisional Financial Performance MeasuresdinaNo ratings yet

- Financial Analysis The Working CapitalDocument6 pagesFinancial Analysis The Working Capitalsumedhkamble136No ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Accounting 3- Segment Reporting and Responsibility AccountingDocument25 pagesFundamentals of Accounting 3- Segment Reporting and Responsibility AccountingAndrew MirandaNo ratings yet

- RMK 9 - Groups 3 - Divisional Financial Performance MeasuresDocument9 pagesRMK 9 - Groups 3 - Divisional Financial Performance MeasuresdinaNo ratings yet

- Developing A TargetDocument6 pagesDeveloping A Targetraja2jayaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Management Accounting Defined, Described, and Compared To Financial Accounting PDFDocument7 pagesChapter 1 Management Accounting Defined, Described, and Compared To Financial Accounting PDFfrieda20093835No ratings yet

- Running Header: Managerial Accounting SummaryDocument10 pagesRunning Header: Managerial Accounting Summaryroshan giriNo ratings yet

- Horngrens Cost Accounting A Managerial Emphasis 16th Edition Datar Solutions ManualDocument25 pagesHorngrens Cost Accounting A Managerial Emphasis 16th Edition Datar Solutions ManualChristinaSmithteydp100% (51)

- Assessment 2 Report: MODULE TITLE: Managing Operations and Finance Course Title: MSC Project Management With AdvancedDocument11 pagesAssessment 2 Report: MODULE TITLE: Managing Operations and Finance Course Title: MSC Project Management With AdvancedAnonymous zXwP003No ratings yet

- Dwnload Full Horngrens Cost Accounting A Managerial Emphasis 16th Edition Datar Solutions Manual PDFDocument36 pagesDwnload Full Horngrens Cost Accounting A Managerial Emphasis 16th Edition Datar Solutions Manual PDFaffluencevillanzn0qkr100% (10)

- Business Notes Plus Button Battery SpeechDocument14 pagesBusiness Notes Plus Button Battery Speechhussainshakeel.mzNo ratings yet

- Bases de CostosDocument13 pagesBases de CostosNohemi LopezNo ratings yet

- Cost Accounting Final Edition - July 8Document204 pagesCost Accounting Final Edition - July 8Noah Mzyece Dhlamini100% (1)

- Uses of Management Accounting: Record KeepingDocument5 pagesUses of Management Accounting: Record Keepingisfaq_kNo ratings yet

- Managerial AccountingDocument74 pagesManagerial AccountingCodyxanss100% (1)

- What The Concept of Free Cash Flow?Document36 pagesWhat The Concept of Free Cash Flow?Sanket DangiNo ratings yet

- Responsibility CentresDocument30 pagesResponsibility CentresRafiq TamboliNo ratings yet

- Management of International Operations-IntroDocument51 pagesManagement of International Operations-IntroZeeshan AhmedNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Management AccountingDocument46 pagesIntroduction To Management AccountingBulelwa HarrisNo ratings yet

- Current Focus On Management AccountingDocument3 pagesCurrent Focus On Management AccountingGêmTürÏngånÖ0% (2)

- Part IDocument5 pagesPart IhazeerkeedNo ratings yet

- Types and Objectives of Responsibility CentresDocument9 pagesTypes and Objectives of Responsibility Centresparminder261090No ratings yet

- ManAccP2 - Responsibility AccountingDocument5 pagesManAccP2 - Responsibility AccountingGeraldette BarutNo ratings yet

- Finman IntroductionDocument40 pagesFinman IntroductionimzeeroNo ratings yet

- Responsibility AccountingDocument16 pagesResponsibility AccountingSruti Pujari100% (3)

- Cost Accounting BookDocument197 pagesCost Accounting Booktanifor100% (3)

- Analyzing Divisional Performance and Transfer PricingDocument44 pagesAnalyzing Divisional Performance and Transfer Pricingbryan albert0% (1)

- P5 Apc NOTEDocument248 pagesP5 Apc NOTEprerana pawarNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 1: Business Economics: Learning ObjectivesDocument107 pagesCHAPTER 1: Business Economics: Learning ObjectivesSherikar Rajshri ShivNo ratings yet

- Mcs 5Document40 pagesMcs 5faisal_cseduNo ratings yet

- Managerial Accounting Chapter SummaryDocument13 pagesManagerial Accounting Chapter SummaryShilpi IslamNo ratings yet

- Usl MS 01Document6 pagesUsl MS 01myrnabalisi8No ratings yet

- T2&T4Document204 pagesT2&T4សារុន កែវវរលក្ខណ៍No ratings yet

- Financial Performance MeasuresDocument5 pagesFinancial Performance Measurescattiger123No ratings yet

- Icaew - Ma1 - Lecture Notes - For StudentsDocument101 pagesIcaew - Ma1 - Lecture Notes - For StudentsTung Hoang100% (1)

- Working Capital Management Theory and Applications DissertationDocument62 pagesWorking Capital Management Theory and Applications DissertationZoica PascuNo ratings yet

- Advance Performance Management Assignment for Responsibility Centers and McKinsey's 7S ModelDocument12 pagesAdvance Performance Management Assignment for Responsibility Centers and McKinsey's 7S ModelMohammad HanifNo ratings yet

- Modul: Accounting For Manager (MAN 653)Document29 pagesModul: Accounting For Manager (MAN 653)kiki dutaNo ratings yet

- Responsibility Centers Management AccountingDocument3 pagesResponsibility Centers Management AccountingRATHER ASIFNo ratings yet

- Assignment of Managerial AccountingDocument8 pagesAssignment of Managerial Accountingsammam mahdi samiNo ratings yet

- Learning Objective of The Chapter: Managing Growth and Transaction Preparing For The Launch of The VentureDocument29 pagesLearning Objective of The Chapter: Managing Growth and Transaction Preparing For The Launch of The VentureWêēdhzæmē ApdyræhmæåñNo ratings yet

- ZICA T2 - Cost AccountingDocument204 pagesZICA T2 - Cost AccountingMongu Rice97% (36)

- Topic 1 Managerial Acctg and Business EnvDocument7 pagesTopic 1 Managerial Acctg and Business EnvSueraya ShahNo ratings yet

- Bbac 142 - Managerial Accounting 2022Document8 pagesBbac 142 - Managerial Accounting 2022sipanjegivenNo ratings yet

- CH-5 Analysis of Firm StructureDocument15 pagesCH-5 Analysis of Firm StructureRoba AbeyuNo ratings yet

- AssignmentDocument15 pagesAssignmentagrawal.sshivaniNo ratings yet

- Q.1 Short Notes: A. Impact of Management Style On Management Controls: Ans: The Internal Factor That Probably Has The Strongest Impact On Management Control IsDocument26 pagesQ.1 Short Notes: A. Impact of Management Style On Management Controls: Ans: The Internal Factor That Probably Has The Strongest Impact On Management Control IsJoju JohnyNo ratings yet

- Unit 1-4Document104 pagesUnit 1-4ዝምታ ተሻለNo ratings yet

- Responsibility Accounting An OverviewDocument8 pagesResponsibility Accounting An OverviewRiza May Kristin C. AcmaNo ratings yet

- Benchmarking Best Practices for Maintenance, Reliability and Asset ManagementFrom EverandBenchmarking Best Practices for Maintenance, Reliability and Asset ManagementNo ratings yet

- BSP Auto Reconciliation: Dolphin Dynamics LTDDocument24 pagesBSP Auto Reconciliation: Dolphin Dynamics LTDGkæ E. GaleakelweNo ratings yet

- Acca SBR s18 NotesDocument146 pagesAcca SBR s18 NotesGEDDIGI BHASKARREDDY100% (1)

- An Investigation Into The Impact of The Adoption of Third Generation (3G) Wireless Technology On The Economy, Growth and Competitiveness of A Country. by Galeakelwe Kolaatamo.Document58 pagesAn Investigation Into The Impact of The Adoption of Third Generation (3G) Wireless Technology On The Economy, Growth and Competitiveness of A Country. by Galeakelwe Kolaatamo.Gkæ E. GaleakelweNo ratings yet

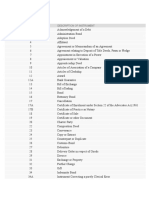

- Table of ContentsDocument1 pageTable of ContentsGkæ E. GaleakelweNo ratings yet

- GoodDocument1 pageGoodGkæ E. GaleakelweNo ratings yet

- Admission Offers 2010-11Document8 pagesAdmission Offers 2010-11Gkæ E. GaleakelweNo ratings yet

- Management Accounting Mega DriveDocument6 pagesManagement Accounting Mega DriveGkæ E. GaleakelweNo ratings yet

- Formulae For The Computation of The VariancesDocument5 pagesFormulae For The Computation of The VariancesGkæ E. GaleakelweNo ratings yet

- 2nd Sem PDM SyllabusDocument11 pages2nd Sem PDM SyllabusVinay AlagundiNo ratings yet

- Cash Flow and Financial PlanningDocument64 pagesCash Flow and Financial PlanningKARL PASCUANo ratings yet

- BASO Presentation PDFDocument25 pagesBASO Presentation PDFGEOEXPLOREMINPERU MINERÍA Y GEOLOGIANo ratings yet

- Accounting For ReceivablesDocument4 pagesAccounting For ReceivablesMega Pop Locker50% (2)

- Atlas Honda - Balance SheetDocument1 pageAtlas Honda - Balance SheetMail MergeNo ratings yet

- Personal Finance PowerPointDocument15 pagesPersonal Finance PowerPointKishan KNo ratings yet

- LatAm Fintech Landscape - 2023Document3 pagesLatAm Fintech Landscape - 2023Bruno Gonçalves MirandaNo ratings yet

- Jupiter Intelligence Report On Miami-Dade Climate RiskDocument11 pagesJupiter Intelligence Report On Miami-Dade Climate RiskMiami HeraldNo ratings yet

- Eco 411 Problem Set 1: InstructionsDocument4 pagesEco 411 Problem Set 1: InstructionsUtkarsh BarsaiyanNo ratings yet

- Free Accounting Firm Business PlanDocument1 pageFree Accounting Firm Business PlansolomonNo ratings yet

- ch03 - Free Cash Flow ValuationDocument66 pagesch03 - Free Cash Flow Valuationmahnoor javaidNo ratings yet

- Jharkhand Govt Gazette Regarding Stipend For LawyersDocument6 pagesJharkhand Govt Gazette Regarding Stipend For LawyersLatest Laws TeamNo ratings yet

- E Stamp ArticleDocument2 pagesE Stamp ArticleShubh BanshalNo ratings yet

- Delhi Rent Control Act, 1958Document6 pagesDelhi Rent Control Act, 1958a-468951No ratings yet

- KV Recruitment 2013Document345 pagesKV Recruitment 2013asmee17860No ratings yet

- 1532407706ceb Long Term Generation Expansion Plan 2018-2037 PDFDocument230 pages1532407706ceb Long Term Generation Expansion Plan 2018-2037 PDFTirantha BandaraNo ratings yet

- Sino-Forest 2010 ARDocument92 pagesSino-Forest 2010 ARAnthony AaronNo ratings yet

- KOMALDocument50 pagesKOMALanand kumarNo ratings yet

- Transfer PricingDocument12 pagesTransfer PricingMark Lorenz100% (1)

- Reauthorization of The National Flood Insurance ProgramDocument137 pagesReauthorization of The National Flood Insurance ProgramScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Alagappa University DDE BBM First Year Financial Accounting Exam - Paper2Document5 pagesAlagappa University DDE BBM First Year Financial Accounting Exam - Paper2mansoorbariNo ratings yet

- Management of Mineral EconomyDocument7 pagesManagement of Mineral EconomyChola MukangaNo ratings yet

- A Study On Investors Buying Behaviour Towards Mutual Fund PDF FreeDocument143 pagesA Study On Investors Buying Behaviour Towards Mutual Fund PDF FreeRathod JayeshNo ratings yet

- Joseph Showry MBADocument3 pagesJoseph Showry MBAjosephshowryNo ratings yet

- Breaking The Time Barrier PDFDocument70 pagesBreaking The Time Barrier PDFCalypso LearnerNo ratings yet

- Grant Thornton Dealtracker H1 2018Document47 pagesGrant Thornton Dealtracker H1 2018AninditaGoldarDuttaNo ratings yet

- Gram Yojana (Gram Priya) 10 Years Rural Postal Life Insurance Age at Entry Yrs Annual Rs Halfyearly Rs Quarterly Rs Monthly Age at Entry YrsDocument2 pagesGram Yojana (Gram Priya) 10 Years Rural Postal Life Insurance Age at Entry Yrs Annual Rs Halfyearly Rs Quarterly Rs Monthly Age at Entry YrsPriya Ranjan KumarNo ratings yet

- 1st PB-TADocument12 pages1st PB-TAGlenn Patrick de LeonNo ratings yet

- Credit Rating AgenciesDocument40 pagesCredit Rating AgenciesSmriti DurehaNo ratings yet

- Analysis On The Proposed Property Tax AssessmentDocument32 pagesAnalysis On The Proposed Property Tax AssessmentAB AgostoNo ratings yet