Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Dvar Torah - Sarah and Hagar2

Uploaded by

Prosserman JCCOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Dvar Torah - Sarah and Hagar2

Uploaded by

Prosserman JCCCopyright:

Available Formats

Dvar Torah Sarah and Hagar

Intro When we were first asked to do the Dvar Torah this Rosh Hashanah my wife and I were overwhelmed and apprehensive we had never done a Dvar Torah before and did not know how to start writing one so we were tempted to decline the honour. But how can one say no to the rabbi? After some confusion about which parsha we were to talk about, we were even more anxious the story of Sarah and Hagar this didnt seem to be a very nice story. We werent sure what wisdom there was in the story for us, or why it was given such a prominent place in the Torah as the reading for the beginning of the year! And so we started to learn. We read. And downloaded. And asked questions, and then discussed with each other, and then with friends and family. And, as things go when one starts to study anything from fixing pipes to working a computer, we learned. And as we learned, our enthusiasm about the story grew. We learned that there are many lessons and many applications to our world today in the complex story of Sarah and Hagar. And we learned some of the reasons that the story was given such prominence in the Torah and why it is the lead-in for the days of awe. The Story The story, at its simplest level is as follows: Avraham and Sarah are unable to have children even though God had three times promised that Abraham would be the father of a great nation. In an attempt to address this inadequacy Sarah asks Abraham to take her maidservant Hagar and to have children with her. In doing so, Sarah promises that she will be able to handle the complex set of emotions that this situation is likely to generate. Abraham agrees and soon impregnates Hagar. Predictably, tension arises between Sarah and Hagar.

Abraham does nothing to resolve the situation but leaves Sarah to deal with Hagar. Soon the pregnant Hagar flees the household. However an angel appears to Hagar by a fountain of water and begs her to return, assuring her that she will bear a son named Ishmael. Incidentally we learned that it is at this time that Hagar names the God who spoke to her as El-Ro-i - the God who sees. The place where this occurs is called Beer Lehairo-i and is now believed to be Mecca. So Hagar returns to the home of Sarah and Avraham and bears them a son. The second part of the story occurs years later after Sarah has finally conceived and delivered a child (Isaac) to Avraham. At this time Ishmael is a teenager and at Isaacs weaning ceremony, he makes some comment or joke about his half brother that incenses Sarah. Sarah asks Avraham to send Hagar and Ishmael into the desert, ostensibly to die. Avraham is torn between Sarah and his son Ishmael whom he loves. God urges Avraham to listen to Sarah and he does. Hagar and Ishmael are sent into the desert with only a skin of water. Hagar carries her starving son through the desert until God appears a second time to Hagar, saving her life, and again promising that her son will lead a great nation. What we learned: In this Dvar Torah we have chosen to focus on the complex relationships in this story the familial relationship between Sarah and Avraham, the strained relationship with a stranger or outsider (Sarah and Hagar) and the relationships between man and woman -and God. 1. Sarah and Abraham The relationship between Sarah and Avraham in this story is perplexing. The couple seems materially comfortable, and has been promised a bright future, but they are unable to produce a child together, which makes them unhappy. This story shows Abraham as being rather passive in his relationship with Sarah. For example, he agrees to impregnate Hagar, despite being aware of the problems this could create. 2

He also leaves the jealous Sarah alone to deal with the pregnant Hagar and does not intervene when there is disagreement between the two, or when Hagar leaves. Years later, Avraham does show some backbone when he is reluctant to comply with Sarahs urging him to ban Hagar and Ishmael to the desert but we are lead to believe that this is because of his love for Ishmael and not necessarily the ethics of the situation. But when God urges Abraham to comply with Sarahs request he does agree to banish Hagar and Ishmael. The story gives us the picture of an unhappy couple where the husband will do anything to keep the wife happy, even if he knows that what he is doing could be morally wrong or lead to further problems down the road. So what can we take from the relationship between Sarah and Abraham in this parsha? How can we apply this situation to our own lives in modern times? This is not a big leap. We are all in relationships with partners and family and friends where we do not always act in good conscience. We may be too passive, too anxious to please, too eager to reduce conflict. We dont always pay attention to the root of the conflict, and often just acquiesce to what our partner or friend or relative is asking for. The message of the story then may be that by behaving this way we are not being honest with our peers or respectful of our relationships. The story may also be warning that these situations can come back to bite us later on in our lives. That is, we may pay for the consequences for our inattention or passivity later on in our lives, as Abraham did. One can even apply this principle to the political realm, where we are now in Israel as a nation in the Middle East experiencing the negative effects of our inattention to the Palestinian peoples over the past six decades. 2. Sarah and Hagar

The relationship between Sarah and Hagar is a source of additional strife in the relationship arena. The mother of our people, Sarah, is jealous of Hagar and consequently is mean and abusive towards her. Hagar is an outsider - living as a stranger and a servant in Sarahs house. She is used- as a surrogate mother - to compensate for Sarahs infertility. Hagar shares the upbringing of her child with Sarah. However, Sarah is the balabusta or boss and has power over Hagar in the household and in childrearing. While there is some indication that Hagar has made a comment to indicate that Sarah was inadequate, which would have incensed Sarah, the ultimate power is in Sarahs hands and she does not seem to use it wisely or kindly - even to the point of acquiescing to the possible deaths of Hagar and Ishmael when they are banished to the desert with minimal water and no food. Why was our fore-mother so cruel to the stranger in her household? And what can we learn from this aspect of the story? This is where the Torah shows us what we need to learn about human nature and relationships in order to be truly just and honest. Perhaps it is human nature to be jealous. And perhaps it is in our nature to be fearful of strangers, sometimes to the point of abusing them if we have the power to do so. These are not admirable traits. So this Rosh Hashanah, as we look into our own behaviours and relationships, perhaps we will have to work doubly hard to minimize these traits in ourselves. Perhaps we should attempt to be more open to strangers and more inclusive of the outsiders among us. Perhaps we should try to contain our instincts to be petty and jealous, and instead be more likely to give others the benefit of the doubt and, if something bothers us - to let it go or, sit down at the bargaining table and learn how to work it out.

3. Man and woman and God

Ultimately, it is the role of God in this story that is most perplexing. God appears to be directing the players and the outcomes of this story; and yet He is allowing them to display jealousy and outright cruelty. Ultimately, He intervened and saved and blessed Hagar and Ishmael, as well as blessing Sarah and Abraham with a son of their own. So what is the learning point here? The Book of Genesis is filled with accounts of God proclaiming He is the one true God and testing mans belief and faith. Man often failed and ultimately was taught a lesson by God. It certainly made us ask - Why? And why did Hagar and Ishmael have to come so close to death before God intervened? I would like to theorize that there are many lessons in this story, but the outstanding ones are lessons of tolerance, lessons of human nature, and warnings of the consequences of not hearing, not listening to and not respecting one another. Sarah obviously misjudged her own tolerance when she suggested to Abraham that he impregnate Hagar and that would not trouble her. But God did continue to guide them he told Abraham to listen to Sarah did he mean to banish Hagar and Ishmael, or could he have meant to hear her unhappiness and find a more equitable solution. My belief lies in this domain that Abraham did not truly hear and God had to save the day. Perhaps God was testing the mettle of Sarah and Abraham by making them live with a stranger and fail at the attempt? Perhaps God was testing Avrahams faith and setting him up for the next test - the Akedah? But that is for the Dvar Torah tomorrow. Or was God telling the children of Israel that because of the expulsion of Hagar and Ishmael and the difficult birth of the Muslim nation, we would need a continuous reminder - through the ages -of the need to listen and hear; to be kinder to our brothers; and of the need to examine our relationships with those whom we consider as outsiders in this world?

On a personal note, over the past year our family has been held to account on our own feelings about welcoming strangers into our lives. One of our children has brought home a Muslim partner. This has forced us to examine our own values and beliefs and to alter and adapt our behaviours as well as family customs. It has been a test of our liberalism and our openness and it is a work in progress. Conclusion The story of Sarah and Hagar is perplexing and difficult on many levels. It causes us to question our relationships and our prejudices. It emphasizes how relationships can be challenging for us because we are human, and it demonstrates that it has always been in our nature to struggle with forces of jealousy, a fear of strangers, hunger for power over others, and an inability to follow through on our promises. It also must impress upon us the need to truly hear what is being expressed to us and not react to our own needs and emotions. To us the outstanding message in this parsha is that over the next 10 days, as we attempt the psycho-social inventory that is the work of Rosh Hashanah, we need to focus our efforts on how to build, maintain and nurture our relationships within our families, with our communities, with the rest of the world, and with God. It is imperative that we try to understand the plight of others and not react to our own hidden insecurities. In this spirit, we wish ourselves and the entire congregation good fortune in these endeavors! Shana Tova!

You might also like

- HAGAR Bible StudyDocument5 pagesHAGAR Bible Studyknowme73No ratings yet

- She Speaks - Wisdom From The Women of The Bible To The Modern Black WomanDocument12 pagesShe Speaks - Wisdom From The Women of The Bible To The Modern Black WomanThomas Nelson BiblesNo ratings yet

- Notes About Sarah The PriestessDocument2 pagesNotes About Sarah The PriestessSusana Sidhe Aguilar50% (2)

- The Origins of The CalendarDocument4 pagesThe Origins of The Calendarafiffarhan2No ratings yet

- The Word Became FleshDocument2 pagesThe Word Became FleshPret ZelNo ratings yet

- Judeo Arabic LanguagesDocument5 pagesJudeo Arabic Languagesdzimmer6No ratings yet

- The Origin of The Names of Angels and Demons The Extra-Canonical Apocalyptic Literature To 100Document12 pagesThe Origin of The Names of Angels and Demons The Extra-Canonical Apocalyptic Literature To 100Oscar Mendoza Orbegoso100% (1)

- HagarDocument10 pagesHagardavidNo ratings yet

- Sarah Plain and Tall2Document11 pagesSarah Plain and Tall2api-306091863100% (1)

- The Inner Meaning of The Siva LingaDocument35 pagesThe Inner Meaning of The Siva LingaSivason100% (1)

- The Women of the Bible Speak Workbook: The Wisdom of 16 Women and Their Lessons for TodayFrom EverandThe Women of the Bible Speak Workbook: The Wisdom of 16 Women and Their Lessons for TodayNo ratings yet

- Way of The Cross For Visita Iglesia - ReviseDocument24 pagesWay of The Cross For Visita Iglesia - ReviseJohnmariya SaranilloNo ratings yet

- The Prayer of Hannah: Healing a Sorrowful SpiritFrom EverandThe Prayer of Hannah: Healing a Sorrowful SpiritNo ratings yet

- Barrenness and Blessing: Abraham, Sarah, and the Journey of FaithFrom EverandBarrenness and Blessing: Abraham, Sarah, and the Journey of FaithRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- E.G. Browne and Baha'i FaithDocument98 pagesE.G. Browne and Baha'i FaithdrevenackNo ratings yet

- HagarDocument6 pagesHagarLily KingNo ratings yet

- Nothing New Under the Sun: Lessons on Living from Women of the BibleFrom EverandNothing New Under the Sun: Lessons on Living from Women of the BibleNo ratings yet

- Sermon - The Stories We Do Not TellDocument11 pagesSermon - The Stories We Do Not TellbujacNo ratings yet

- The Burden of The BondwomanDocument6 pagesThe Burden of The Bondwomaniamtheprofessor1995No ratings yet

- In Defense of Sarah: Instant Bible Insights: God's New Nation, #1From EverandIn Defense of Sarah: Instant Bible Insights: God's New Nation, #1No ratings yet

- In The Midst of The Mess - Hagar and The God Who Sees - CBEDocument3 pagesIn The Midst of The Mess - Hagar and The God Who Sees - CBEJoshua PrakashNo ratings yet

- Rosh Hashana 5783Document14 pagesRosh Hashana 5783api-233380695No ratings yet

- The Patriarchs: Sometimes the Stars, Sometimes the SandFrom EverandThe Patriarchs: Sometimes the Stars, Sometimes the SandNo ratings yet

- The Stone Angel Analysis AssignmentDocument6 pagesThe Stone Angel Analysis AssignmentKarinaNo ratings yet

- HAGAR Bible Study - 1Document5 pagesHAGAR Bible Study - 1knowme73No ratings yet

- Parshas Vaerah - Sarah'S Laugh: Rabbi Maury GrebenauDocument2 pagesParshas Vaerah - Sarah'S Laugh: Rabbi Maury Grebenauoutdash2No ratings yet

- Abraham's Bind: & Other Bible Tales of Trickery, Folly, Mercy and LoveFrom EverandAbraham's Bind: & Other Bible Tales of Trickery, Folly, Mercy and LoveNo ratings yet

- The Woman Who Lost A Bottle But Found A WellDocument4 pagesThe Woman Who Lost A Bottle But Found A WellKevinPaulMasmodiLaviňaNo ratings yet

- Bible EssayDocument3 pagesBible Essayapi-377552614No ratings yet

- Introductory Study For Parsha #3: Lech Lecha Torah Haftarah B'rit ChadashaDocument16 pagesIntroductory Study For Parsha #3: Lech Lecha Torah Haftarah B'rit ChadashaDayal nitaiNo ratings yet

- Isomo Ryo Kwigisha Abana Ijambo Ry'imana - Middle & Upper ClassDocument5 pagesIsomo Ryo Kwigisha Abana Ijambo Ry'imana - Middle & Upper Classhakialex_339561049No ratings yet

- Salem Witch Trials Research Paper OutlineDocument7 pagesSalem Witch Trials Research Paper Outlinefyrqkxfq100% (1)

- Women in The Bible01Document5 pagesWomen in The Bible01realangelinemylee2020721001No ratings yet

- "By Faith Sarah Herself Also Received Strength To Conceive SeedDocument25 pages"By Faith Sarah Herself Also Received Strength To Conceive SeedSandra100% (1)

- What's My Name?: Vignettes of Seventy Incredible Bible CharactersFrom EverandWhat's My Name?: Vignettes of Seventy Incredible Bible CharactersNo ratings yet

- Case Study Lesson 9Document4 pagesCase Study Lesson 9Beatriz Ackermann50% (2)

- Anjuman - Daughters Are A Ticket To JannahDocument10 pagesAnjuman - Daughters Are A Ticket To JannahnikbelNo ratings yet

- Hagar and Ishmael: Genesis 16Document8 pagesHagar and Ishmael: Genesis 16Chillik ArdiantoNo ratings yet

- 2001 Issue 2 - The Hebrews Hall of Faith Part 4 - Counsel of ChalcedonDocument9 pages2001 Issue 2 - The Hebrews Hall of Faith Part 4 - Counsel of ChalcedonChalcedon Presbyterian ChurchNo ratings yet

- Characterisation of Hagar ShipleyDocument8 pagesCharacterisation of Hagar ShipleyNihari BhupathirajuNo ratings yet

- Women of The Old Testament PDFDocument22 pagesWomen of The Old Testament PDFScribdTranslationsNo ratings yet

- Summary of Max Lucado & Jenna Lucado Bishop's Ten Women of the Bible Study GuideFrom EverandSummary of Max Lucado & Jenna Lucado Bishop's Ten Women of the Bible Study GuideNo ratings yet

- The Age of Patriarchs 2Document28 pagesThe Age of Patriarchs 2EFGNo ratings yet

- Will "We" Ever Understand That Today..or in The Future????Document6 pagesWill "We" Ever Understand That Today..or in The Future????Matt CrichtonNo ratings yet

- Eblast Hocus PocusDocument1 pageEblast Hocus PocusProsserman JCCNo ratings yet

- J.Roots: םיִּאַּבֲה םיִּכוּרְּב ! Welcome toDocument4 pagesJ.Roots: םיִּאַּבֲה םיִּכוּרְּב ! Welcome toProsserman JCCNo ratings yet

- Yom Haatzmaut FlyerDocument1 pageYom Haatzmaut FlyerProsserman JCCNo ratings yet

- Itinerary For Jewish NYCDocument2 pagesItinerary For Jewish NYCProsserman JCCNo ratings yet

- JRoots Teens Club CalendarDocument3 pagesJRoots Teens Club CalendarProsserman JCCNo ratings yet

- High Holy Day 5772/2011 TicketsDocument1 pageHigh Holy Day 5772/2011 TicketsProsserman JCCNo ratings yet

- Focus On The Future: Families With Young ChildrenDocument2 pagesFocus On The Future: Families With Young ChildrenProsserman JCCNo ratings yet

- Kolel Spring / Summer 2011 ClassesDocument2 pagesKolel Spring / Summer 2011 ClassesProsserman JCCNo ratings yet

- Marsha Quiles Yartzeit ShiurDocument1 pageMarsha Quiles Yartzeit ShiurProsserman JCCNo ratings yet

- Treasures in Jewish Literature 2011-12Document1 pageTreasures in Jewish Literature 2011-12Prosserman JCCNo ratings yet

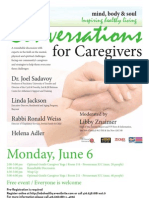

- Conversations For CaregiversDocument1 pageConversations For CaregiversProsserman JCCNo ratings yet

- Spring / Summer 2011 Program GuideDocument37 pagesSpring / Summer 2011 Program GuideProsserman JCCNo ratings yet

- Prosserman JCC Fall 2010 Program GuideDocument40 pagesProsserman JCC Fall 2010 Program GuideProsserman JCCNo ratings yet

- Winter 2011 Program GuideDocument45 pagesWinter 2011 Program GuideProsserman JCCNo ratings yet

- Family DayDocument1 pageFamily DayProsserman JCCNo ratings yet

- Mindfulness Based Stress ReductionDocument1 pageMindfulness Based Stress ReductionProsserman JCCNo ratings yet

- Functional Mobility TestingDocument1 pageFunctional Mobility TestingProsserman JCCNo ratings yet

- Growing Healthy FamiliesDocument1 pageGrowing Healthy FamiliesProsserman JCCNo ratings yet

- ChanukahDocument1 pageChanukahProsserman JCCNo ratings yet

- Upcoming Events at KolelDocument2 pagesUpcoming Events at KolelProsserman JCCNo ratings yet

- Rosh Hashanah 2010Document1 pageRosh Hashanah 2010Prosserman JCCNo ratings yet

- We Want To Hear From YouDocument1 pageWe Want To Hear From YouProsserman JCCNo ratings yet

- Kolel High Holy Day Early Bird InfoDocument1 pageKolel High Holy Day Early Bird InfoProsserman JCCNo ratings yet

- Book of Proverbs: The Young and The RestlessDocument5 pagesBook of Proverbs: The Young and The RestlessLahcen AkhoullouNo ratings yet

- BG Chapter 7Document11 pagesBG Chapter 7Rohit Kumar BaghelNo ratings yet

- 5.26 Saint Philip NeriDocument2 pages5.26 Saint Philip Neristephanie kershisnikNo ratings yet

- Ahab PaperDocument20 pagesAhab PapertjbickertNo ratings yet

- 10 Great Fatwas of Aala Hadrat Imam Ahmed Raza Khan RHDocument9 pages10 Great Fatwas of Aala Hadrat Imam Ahmed Raza Khan RHsahebjuNo ratings yet

- 2018 10 28 and The Greatest of These Is Love PDFDocument3 pages2018 10 28 and The Greatest of These Is Love PDFNamang CarolineNo ratings yet

- Basis For AuthorityDocument5 pagesBasis For AuthorityANTONIO ROMAN LUMANDAZNo ratings yet

- Cleansing The Inner Vessel PDFDocument3 pagesCleansing The Inner Vessel PDFR&DExactIloiloNo ratings yet

- Did Mary Have Other Children After Jesus Was BornDocument12 pagesDid Mary Have Other Children After Jesus Was BornJesus LivesNo ratings yet

- Religion FPD 2Document13 pagesReligion FPD 2api-396792809No ratings yet

- Dars-e-Tauheed: by Al-Haaj Maulana Muhammad Shafee Sahib OkarviDocument26 pagesDars-e-Tauheed: by Al-Haaj Maulana Muhammad Shafee Sahib OkarvinewgalaxianNo ratings yet

- Last 2 Ayat of Surah Baqarah (Translation, TranslDocument2 pagesLast 2 Ayat of Surah Baqarah (Translation, TranslNadirNo ratings yet

- ReEd 2 Lesson 3 History and Formation of The Bible and The CanonDocument3 pagesReEd 2 Lesson 3 History and Formation of The Bible and The CanonFLORIVEN MONTELLANONo ratings yet

- Silence in The Sacred LiturgyDocument18 pagesSilence in The Sacred Liturgynjknutson3248100% (1)

- Romanian Origins (I)Document6 pagesRomanian Origins (I)v2adutNo ratings yet

- Excerpts From The UpanishadsDocument5 pagesExcerpts From The Upanishadsdoan anhNo ratings yet

- Ethics & Fiqh For Everyday Life PDFDocument255 pagesEthics & Fiqh For Everyday Life PDFFaIz Fauzi100% (1)

- Veritas Vos Liberabit - WikipediaDocument2 pagesVeritas Vos Liberabit - WikipediaLeucippusNo ratings yet

- That Art ThouDocument287 pagesThat Art ThouKumar SubramanianNo ratings yet

- The Amazing Collection of Holy QuranDocument3 pagesThe Amazing Collection of Holy Quranni1wawin6813No ratings yet

- Here I Stand ReviewDocument5 pagesHere I Stand Reviewdabrsfn100% (1)

- Best Sellers CbaDocument8 pagesBest Sellers Cbasophia_stephy9478No ratings yet

- South Asia Institute of Advanced Christian StudiesDocument4 pagesSouth Asia Institute of Advanced Christian StudiesPauline KutNo ratings yet