Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Lawler Greek Dance

Uploaded by

mprussoOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Lawler Greek Dance

Uploaded by

mprussoCopyright:

Available Formats

The Dance in Ancient Greece Author(s): Lillian Brady Lawler Source: The Classical Journal, Vol. 42, No.

6 (Mar., 1947), pp. 343-349 Published by: The Classical Association of the Middle West and South Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3291645 . Accessed: 13/07/2011 16:28

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at . http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=camws. . Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

The Classical Association of the Middle West and South is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Classical Journal.

http://www.jstor.org

The dancemirrored of Greeklife, all and Greekdisposition Greekthought, by Lillian BradyLawler

The

Dance

in

Ancient

Greece

Peace, 816-817

"O divine Muse, join with me in the festival dance!"-Aristophanes, THE Bright Greek sun was high in the flawless blue heavens. It was spring, the manycenturies before Christianera. In the little Greekvillage,on the lower slopes of the greatrockthat was its citadeland the dwelling, placeof its king,the humblehousesof sun-dried brickstood open and deserted,and the goats clambered unrestrained and downthe steep, up narrowstreets;for it was the festival of Arwho temis,goddess givessuccessin the huntand increase amongtheflocksand herds,and all the had villagers goneto the celebration.

OUT ON a shoulder of a low hill, a mile or

so fromthe citadel, was the village threshingfloor.Here, on the greatroundcircleof beaten earth, the precious grain would be trampled and winnowed, later in the year. Now, on this spring festival day, it swarmed with joyous villagers,their long hair oiled and garlanded, their woolen, home-woven"chitons" (or tunics) clean and bright, their massive armletsand broochesgleamingin the sun. In the very center of the threshing-floora small,crude altar of wood had been set up in honor of Artemis; and around it had been

((It is a distinct pleasureto welcome Miss Lawler back to the pages of CJ. Readers will recall her "Portraitof a Dancer"in our March issue last year-"Pylades, Idol of the Roman Empire." Miss Lawlerinformsus that she once studied dancing herself, ballet, folk, and interpretative. In addition to having the necessary groundingin classical scholarship for the study of the ancient dance, she has traveledherself pretty much all over the world to gain an acquaint, ance with native dances-Greece and Italy, Cyprus, Asia Minor, Central and South America, Cuba, China, Japan, Philippines, Hawaii, Fiji Islands, Samoa, New Zealand . . .without neglecting the American Indian, either.

twined a garlandmade of early violets. The crowd milled about it, chatteringhappily, or eating figs, sticky candy made of honey, or cakes baked in the shape of the animalsof Artemis. Besidethe threshing-floor, few boothshad a been erected, of rough, canvas-likecloth and greenboughs.Beneathone, a village musician was playing a minor strain on his squealing little Pan-pipe, while a cluster of admiring neighbors listened and gaped. In another booth a circle of old men sat, their white beardsand long braidedwhite hair contrasting sharply with their wrinkled, weatherreddened skin. One of their number was chanting a lay of heroic deeds of bygone times, his gnarled hands "dancing out" his story in symbolic gesture as he went along. His crackedold voice rose and fell, and his hearers nodded approval, sometimes even to muttering an accompaniment his words. In an adjacentbooth a young woman offered fragrant garlands of spring flowers, to be worn on the head or aroundthe neck. In the booth just beyond, thick, sweet wine and clear, cold water were being dispensed.The vendor, somethingof a village wag, kept up a flow of witticisms in a loud, compelling voice, to the intense delightof the young men among his customers, who now and then joined in the jesting, often to their own dis, comfiture,when the wine-seller turned the barbof his wit upon them, namingnames.

The Dancers Come

Two OFTHE BOOTHS were closed, but from

both came sounds of voices and of subdued, scramblingactivity. From time to time the villagersstopped to stare at them in hopeful anticipation. Finally their patience was re-

343

344

LILLIAN BRADY LAWLER It was in some such setting as this that the dance developed in early Greece. Not all of its manifestationsconsisted in animal mummery, of course;but animaldancesamongthe Greeksare very old and very numerous,and they underliemoreof the dancesof the classical period than even the Greeks themselves suspected. Greek dances passed from primitive simplicity to complex sophistication, down through the centuries, and became infinitelyvaried. all Dancesultimatelymirrored of Greeklife, Greekthought,and the Greekdisposition; and to study the progress the Greekdanceis, in of themselves. a sense,to studytheGreeks To the Greek,the dance was intensely important, ritualistically, personally, socially. Much of his religious activity included dancing. In the dance he endeavored to enter into spiritual kinship with his gods. With the magic of the dance he wardedoff vague but dangerousevil beings, or famine and disease. By dancinghe sought to obtain good crops,to ensurefertility amonghis flocks and in his own household,to be fortunatein the hunt, to gain victories in war. With the dance he hallowed his dramaticfestivals, or revealed solemn mysteries to neophytes. Dancinghad a definiteplacein his education, and it playedan importantpartin his physical and emotionaldevelopment.With the dance he cured nervous disorders.With the dance he created abstractbeauty for its own sake, or amusedhimself.A greatdealof his military trainingtook the form of dancing.By means of the dancehe expressedall his personaland communalemotions of joy and sorrow, and markedall the great events of his own life and that of his city. With the dancehe entertained his guests. With joyous dance he greeted the return of spring; with dance he harvestandvintage,increase celebrated among flocksand herds, births and weddings in his home, successin the hunt and in battle. In a way, the dance symbolizedto very particular him the joy of peace,afterthe terrorof war"dancesare ours," says Tryphiodorus(427-

warded. A flap in the largerbooth was suddenly raised,and, with a loud roarthat was a compositeof numerousanimalcries, a rout of maskeddancersburst upon the scene. Each wore a short woolen chiton and roughsandallike shoes; but these purely humanattributes were cast into oblivionby the greatmask-wig combinations that covered head and neck, turningthe dancerinto a stag, a lion, a bird, a a panther,a boar,a wolf, a griffin, fish.At the end of the line a musician,clad in the long, ungirt robe of his profession,drew his hand acrossthe stringsof his cithara,or hand-harp, and moved with the dancers out upon the threshing-floor. Children squealed with excitement, and clung to their mothers' or their nurses' chitons, as the crowd fell back along the perimeterof the circulardancing,place,and preparedto watch the sacred mummeryin honor of Artemis, "Mistress of Animals." A momentlater, fromthe other closed booth, several small figuresin shaggy yellow-brown bear-costumes,with eared hoods, lumbered forth in assumed awkwardness, amid the laughterand shouts of the spectators.These were the "bears,"the young maidensof the village, who must all "dance the bear" for Artemis once in their lives, beforethey came to the age for marriage. Simplicity to Sophistication

circled the threshing-floor, THE DANCERS

roaring,rearing,pivoting, dartingsuddenlyat the spectators,sometimeseven bowling them over. The little "bears"stampedabout with their "paws" extended, imitating their wild prototypes, to the delight of the villagers. These cheeredtheir favoritesamongthe "animals," laughed, shouted witticisms, threw flowersandcakes,and half-consciously swayed and gesturedin imitationof the dancers.The twanging of the citharawas drownedin the went each generaluproar;and the "animals" his own way, settling his own rhythm, and abandoningit only when, as frequentlyhappened, he collidedwith anotherdancer.Bedlam reigned; and over it all, presumably, 429), "and honey-breathing music, and no morewar. Artemis watched, and was pleased.

THE DANCE IN ANCIENT GREECE

345

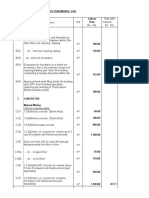

FIGURE

I.

DANCES

IN

HONOR

OP DIONYSUS.

THE

PICTURE SHOWS THE "WING-SLEEVED"

DANCE

OF

WOMEN, PECULIAR TO THE RITUAL OF DIONYSUS. THE DANCE MAY HAVE ORIGINATED OF GREAT ANTIQUITY. (LONDON, BRITISH MUSEUM, E 75).

IN A BIRD DANCE

Among the Greeks,the dance was a social activityin the truest sense of the word.However, our very commonform of the "social" dance,performed a man and a womanto, by gether, for amusement, seems not to have appealedto them;for we have no certainevidenceof anythingquite like it in Greektimes. Ancient and Modern Dance great significance-viz., that the ancient Greek concept of the dance differs considerably from our own. An approachto any phase of an ancientcivilizationrequiressome mentaladjustment the partof the readeron some deliberatecasting off of modem ideas, and conscious orientationto points of view fromthose of his own day essentiallydifferent and age. In no aspect of classicalstudies is

ALL OF THIS emphasizes another point of

this more strikinglytrue than in the field of the dance. To the Greek of the classical his period,for instance, orcheisthai, word for "to dance," seems to have connoted something like "to makeany series of movements, however simple, and involving any part or partsof the body, providedthe movementsbe The Greekcould dancewith his rhythmical." hands,with his head, with his eyes. He quite often dancedwithout movinghis feet at allindeed, even in a sitting position! There is a classicinstance(Herodotus6. I29) of a Greek who dancedwith his legs while standingon his head; and at times the Greek actually speaks of "standingin a dance" (Euripides, Iph. Taur. 1143;cf. Callistratus14. 5). What we call a parade a militarydrillthey would or call a dance;a funeralor wedding procession, or a processionof any sort, a rhythmicgame

346

LILLIAN BRADY LAWLER and poetry, greaterand lesser works alike. In general, Homer, Xenophon, Pollux, Lucian, Athenaeus, and Libaniuswill be found to be most useful. Metrical sourcesare of two kinds-treattises on metrics,by ancient grammarians; and the actuallines of verse to which the ancients danced, wherever these have come down to us. Metrical sourcesareprimary sources;and, information especiallywhere they corroborate from literaryand other sources, they cannot be ignored. Musical sources comprise treatises on music, by ancient writers; remains of the music itself; and a few of the actual musical instrumentsof antiquity, which survive in a What is known of good state of preservation. Greek music must be taken into account in any thoroughgoing study of the ancientdance.

of ball, an exhibitionof jugglingor tumbling, children'sgames,the a tightropeperformance, of the tragicactor,all measured gesticulations were dancesto him.

Dance and Music

FURTHER,

the ancient Greek did not think

of dancingas an art completein itself. In his mind it was inseparablyconnected not only with music (an associationentirely comprehensible to us today), but also with poetry. As a matterof fact, he often "danced" poetry, interpretingthe verses with rhythmicmovements of his arms, body, and head; and an ancient poet (Ausonius, Id. 20. 6) speaks of dancing with the foot, with the voice, and with the countenance, simultaneously. In such activity the Greek evolved what he called cheironomia-a whole code of gestures and symbolicmovementsthe extent and complexity of which are almost beyond our combut prehension, the effectof which even upon foreigners was immediate and convincing. Music, poetry, the dance-to the Greekthey were all facets of the same thing, the art which he called mousikg, the "art of the Muses." In its broadestsense it signifiedto him all of the education of the mind, and, indeed, the very essence of civilization. He says of a barbarousenemy tribe, "For them in there is no significance life; they have no no Helicon, no Muse."1 dancing, For the modern student who wishes to learn something about the dancing of the ancient Greeks there are several avenues of approach.Our "sources"of informationare, in fact, of at least seven different typesepiliterary,metrical,musical,archaeological, graphical,linguistic, and anthropological. The most obvious are literary sourcesspecificstatementsabout the dance made by ancient writers. Almost the whole of Greek literatureis an informalsource for the study of the dance. Mortals, supernatural beings, even animals, dance through its pages; and its very figuresof speech aboundin echoes of the dance. Accordingly, the student who would understand the Greek dance would do well to read widely and deeply in Greek literature,of all periodsand all genres, prose

Sources Archaeological

ARCHAEOLOGICAL

sources on the dance in-

clude tangible objects which have survived fromantiquityto the presenttime, and which furnishrepresentations dancing and dancof or of objects used by dancers. Such ers, objects are extant in large numbers. They include statues in marble and in bronze; in figurines terracottaand in metal;reliefs on plaques,on urns, and on the sides of buildings; choregicmonuments,especially that of Lysicrates;votive cymbalsset up in shrines; delicate carvingson gems, on ivory, on gold and silver jewelry, and on mouldsto be used in the makingof seals;mosaicfloorsand stuccoed ceilings; an occasionalcoin; and paintings, both on walls and on pottery. Archaeological sources are of the first importanceto the student of the ancient dance, and serve to renderthat dance strikinglyvivid. But, on the other hand, no sourcesare so capableof as seriousmisinterpretation are these ancient picturesof the dance, in part becauseof the damaged condition of most of the objects involved, in part becauseof the artistic conventions employedby the ancient artist. In a broad sense, epigraphicalsources are becausethey are actual really archaeological, survivals from antiquity; but so distinctive are they that they may be consideredapart.

THE DANCE IN ANCIENT GREECE They comprise the various ancient inscriptions dealingwith dancingand dancerswhich have come down to us. One of these, the oldest known Attic inscription,is scratched upon a wine-jug which was an award in a dancingcontest. The greatofficial inscriptions on the islandof Delos, where dancingwas of tremendous are ritualisticimportance, a treasure trove for the student of the dance.When used carefully,and when checked with evidence obtained from other sources, inscriptions are of great significance the history for of the dance. "Linguistic sources" are the technical words and expressionsused by the ancients in speaking their dances.In manycases the of only knowledgewhich we have of an ancient danceor figureor step or gestureis its name. The Greeklanguage, it happens,is rich and as flexible.Namesgiven to dancesand figures are usually meant to be descriptive;they can, if we strive to comprehend them correctlyand

347

etymologically, give us a quick and vivid glimpse of the dancer in action. Linguistic study frequently furnishes almost startling corroboration suggestions given by other of sources. It must be remembered,however, that faultyetymologiesareeasy to comeupon, and can serve as dangerouspitfalls for the unwary. Anthropologicalsources are comparative materialsobtainedfroma study of the dance amongvariouspeoplesof the world. For such a study smalland remotevillagesare particularly suitable. Modem Greece, Spain, southern Italy, Sicily, Crete, and Asia Minor show interesting survivals of the Greek dances which were once performed there. Even lands fartherafieldfurnishmaterialfor comparison -Ireland, Cambodia,Japan, Samoa,Africa, India.Also, scatteredrecordsof the dancesof ancient races contemporary with the Greeks -the Egyptians,Hebrews, Phrygians,Thracians-can be illuminating instructive. and

FIGURE

2. A

GRACEFUL DANCE OF THREE WOMEN. THE

THIS

ILLUSTRATES THE TECHNICAL DIFFICULTIES OF

GREEK VASE PAINTING.

IN A CIRCLE. THE FIGURE IN THE REAR, APPARENTLY ELEVATED, IS THOUGHT OF AS ON THE FAR SIDE OF THE CIRCLE. NOTE THE ARTIST'S DIFFICULTY IN PORTRAYING A HEAD BENT BACK OR FORWARD. (LOUVRE ARYBALLOS. Mon. Gr.

ARTIST ENDEAVORS TO SHOW THREE WOMEN DANCING

1889-90, PL. 9-IO).

348

LILLIAN BRADY LAWLER

FIGURE 3. A CEREMONIAL DANCE OF GREEK WOMEN.

It would be ideal to have for each phaseof of the dancea combination all types of source; but that is seldompossible.When a difficulty of interpretationarises in the study of the ancient dance, one must seek a solution by using as many differenttypes of evidence as he can find.

ModernStudies

MODERN INTEREST in the Greek dance, and

attempts to restore and understand it, go back as far as the sixteenth century. The great scholar, Julius Caesar Scaliger,in his treatise On Comedy and Tragedy,devoted much space to ancient Greek dances and figures. A little later, Johannes Meursius, a Dutch scholar, put together an alphabetical catalogueof more than two hundred dances or and figures,to form his Orchestra, On the Dances of the Ancients. From the days of Scaligerand Meursius to the present, there has beena moreor less constantinterestin the ancient dance, althoughthat interest has not resulted in voluminous publication. In general, the subject has been pursued by two groups-professional dancers, and classical scholars. However, the former, who aim

avowedly at a restorationin visible form of the Greek dance, seem conscious of the fact that their lack of knowledge of Greek and archaeologywill inevitably force them into historical errors. The latter, very well groundedin archaeologyand ancient literature, seemto feel an inabilityto cope with the technicalaspects of the dance.This situation has undoubtedly limited work in the field. Further, attempts at collaborationbetween the two groupshave not been successful.

Dances Neo-Greek

the present century, certain new formsof the dance which owe some of their inspirationto the danceof the ancientGreeks have come to the fore, and have attracted wide attention. Many of these have been in the nature of a reaction from the rigorous disciplineof the formalballet dance,fromthe futility and sterility of the dancesof ballroom and theater, and, incidentally, from the restraintsof clothing and mannersof the dancers' own day. Among these Neo-Greek danceformshave been those of IsadoraDuncan, Ruth St. Denis, Ted Shawn, and their of followers, and the "Eurhythmics" JaquesDURING

THE DANCE IN ANCIENT GREECE Dalcroze.There is no question but that the Neo-Greek dance movement has been productive of muchthat is good, especiallyin its educationalaspects. It should be borne in mind, however, that the Neo-Greekdance is not a facsimileof the ancient Greek dance, and that much of it would probablyastonish an ancient Greek beyond measure. On the other hand, if a moder spectator could see any one of severalgenuinelyancientdancesas performedby a Greek of the sixth, fifth, or fourth century before the Christian era, he would be even more astonished. He would hardlyregardit as a danceat all, in any modern senseof the word; and he probablywould neither understand like it-at first sight, nor at any rate. The Greek dance, then, confronts us as quite a problem.There is nothing just like it in existence today, and it must be studied

349

as a distinct entity, with all the aids at our disposal.We shallnever, in all probability,be able to restore-any ancient dance in its entirety; for the very essence of the dance is movement,and movementcan be transmitted from antiquity only indirectly. The best we can hope to do is to study all the evidence available,fromas many angles as possible;to put togetheras manyfacts as we can find,and to make reasonable deductions from those facts. In this way, proceeding slowly and with infinite care, we may attain ultimatelyto an of appreciation what must have been as great an art of the danceas the world has ever seen.

NOTE t). L. Page, GreekLiteraryPapyri,Vol. I, Poetry. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University Press, 1942. No. I43, p. 598, lines 18-I9. Fifth century after Christ, anonymous.

FIGURE 4. KOMOS DANCERS OF THE SIXTH CENTURY. A KOMOS DANCE IS A DANCE OF JOY AND HIGH SPIRITS, AND IS OFTEN ASSOCIATED WITH DRINKING. THE ATTITUDES OF THE FIGURES ARE PHYSICALLY IMPOSSIBLE 1F ONE ATTEMPTS TO INTERPRET THEM EXACTLY AS DRAWN, BUT ARE QUITE UNDERSTANDABLE IF ONE INTERPRETS THEM IN THE LIGHT OF ARTISTIC CONVENTION AND GENERAL COMMON SENSE.

You might also like

- Lesbian Peoples Material For A DictionaryDocument180 pagesLesbian Peoples Material For A DictionaryHosein Jalilvand50% (2)

- The History Of Dance - Gipsy, Hungarian, Bohemian, Russian, And Polish DancesFrom EverandThe History Of Dance - Gipsy, Hungarian, Bohemian, Russian, And Polish DancesNo ratings yet

- Pneuma Aristotle BosDocument19 pagesPneuma Aristotle BosmprussoNo ratings yet

- 2 The Works of John Dee PDFDocument260 pages2 The Works of John Dee PDFmprusso100% (1)

- Margotthe Cat Crochet PatternDocument12 pagesMargotthe Cat Crochet Patternnatalie cortezNo ratings yet

- Years of Fashion - The History of CostumeDocument456 pagesYears of Fashion - The History of CostumePablo Manzanelli95% (19)

- Battle of LifeDocument88 pagesBattle of LifeAmin MandomiNo ratings yet

- Una of The Hill Country1911 by Craddock, Charles Egbert (AKA Mary Noailles Murfree)Document16 pagesUna of The Hill Country1911 by Craddock, Charles Egbert (AKA Mary Noailles Murfree)Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- The Mirror of Taste, and Dramatic Censor Vol I, No. 2, February 1810From EverandThe Mirror of Taste, and Dramatic Censor Vol I, No. 2, February 1810No ratings yet

- Music in Chinese Fairytale and Legend Author(s) : Frederick H. MartensDocument29 pagesMusic in Chinese Fairytale and Legend Author(s) : Frederick H. MartensSedge100% (2)

- The Battle of LifeDocument61 pagesThe Battle of LifeMuhammad Omer Bin SaeedNo ratings yet

- Early Journal Content On JSTOR, Free To Anyone in The WorldDocument34 pagesEarly Journal Content On JSTOR, Free To Anyone in The WorldjcsolanasNo ratings yet

- The Battle of Life. A Love Story - Charles DickensFrom EverandThe Battle of Life. A Love Story - Charles DickensRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (43)

- Negro Folk Rhymes: Wise and Otherwise: With a StudyFrom EverandNegro Folk Rhymes: Wise and Otherwise: With a StudyNo ratings yet

- Costumes of EuropeDocument150 pagesCostumes of EuropeUTpenguin100% (4)

- The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction Volume 19, No. 551, June 9, 1832From EverandThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction Volume 19, No. 551, June 9, 1832No ratings yet

- The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction Volume 19, No. 551, June 9, 1832From EverandThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction Volume 19, No. 551, June 9, 1832No ratings yet

- The Gnomes of the Saline Mountains: A Fantastic NarrativeFrom EverandThe Gnomes of the Saline Mountains: A Fantastic NarrativeNo ratings yet

- English II: Tragedy in Our Midst Using The RAP Strategy To Take Notes Over Nonfiction Strategies of Greek Tragedy: The Chorus and The Structure ofDocument7 pagesEnglish II: Tragedy in Our Midst Using The RAP Strategy To Take Notes Over Nonfiction Strategies of Greek Tragedy: The Chorus and The Structure ofbrm17721No ratings yet

- The Battle Of Life: “I have been bent and broken, but - I hope - into a better shape.”From EverandThe Battle Of Life: “I have been bent and broken, but - I hope - into a better shape.”No ratings yet

- Dwnload Full Geotechnical Earthquake Engineering 1st Edition Kramer Solutions Manual PDFDocument35 pagesDwnload Full Geotechnical Earthquake Engineering 1st Edition Kramer Solutions Manual PDFbenjaminmfp7hof100% (9)

- Fowler1994EgyptianLoveLyrics ACCESSIBLEDocument19 pagesFowler1994EgyptianLoveLyrics ACCESSIBLEEzra GearhartNo ratings yet

- The Story of Ariadne Theseus MinotaurDocument3 pagesThe Story of Ariadne Theseus MinotaurCDavis87123No ratings yet

- Oxford University Press The Musical Quarterly: This Content Downloaded From 62.43.78.219 On Sat, 03 Mar 2018 15:52:35 UTCDocument15 pagesOxford University Press The Musical Quarterly: This Content Downloaded From 62.43.78.219 On Sat, 03 Mar 2018 15:52:35 UTCGracia LlorcaNo ratings yet

- Jason-The End by Athol FugardDocument10 pagesJason-The End by Athol FugardGui HuaiNo ratings yet

- Dances of Rumania 00 GrinDocument48 pagesDances of Rumania 00 Grinjcsolanas100% (1)

- Mangrini, Manhood and Music in W. CreteDocument32 pagesMangrini, Manhood and Music in W. CreteYiannis Alygizakis100% (1)

- Sylvia Parker: Claude Debussy's GamelanDocument10 pagesSylvia Parker: Claude Debussy's GamelanbarrenjerNo ratings yet

- Instant Download Illustrated Microsoft Office 365 and Access 2016 Introductory 1st Edition Friedrichsen Solutions Manual PDF Full ChapterDocument32 pagesInstant Download Illustrated Microsoft Office 365 and Access 2016 Introductory 1st Edition Friedrichsen Solutions Manual PDF Full ChapterKellyBurtoncbjq100% (8)

- The American Songbag (Carl Sandburg) (PVG)Document528 pagesThe American Songbag (Carl Sandburg) (PVG)Cimarron1989No ratings yet

- Dances of Greece 00 CrosDocument48 pagesDances of Greece 00 Crosjuan carlos Güemes cándida dávalosNo ratings yet

- Twice-Told Tales The Maypole of Merry MountDocument5 pagesTwice-Told Tales The Maypole of Merry MountParvez AhamedNo ratings yet

- Taylor & Francis, Ltd. Folklore Enterprises, LTDDocument3 pagesTaylor & Francis, Ltd. Folklore Enterprises, LTDMario Richard SandlerNo ratings yet

- Chinese MusicDocument96 pagesChinese MusicAntonio Masi100% (2)

- Achille, LT 1943 Carnival in Martin PDFDocument10 pagesAchille, LT 1943 Carnival in Martin PDFagardjonesNo ratings yet

- The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction Volume 19, No. 551, June 9, 1832 by VariousDocument36 pagesThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction Volume 19, No. 551, June 9, 1832 by VariousGutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- Anywhere The Wind BlowsDocument1 pageAnywhere The Wind BlowsStephanie SamahaNo ratings yet

- Traditional Greek DancesDocument2 pagesTraditional Greek DancesCamilo RayleighNo ratings yet

- Percussion Instruments of Ancient GreeceDocument3 pagesPercussion Instruments of Ancient GreeceJirapreeya PattarawaleeNo ratings yet

- Berry African Cultural Memory in New OrleansDocument11 pagesBerry African Cultural Memory in New OrleansjfbagnatoNo ratings yet

- Civilization of Ancient EgyptDocument188 pagesCivilization of Ancient EgyptNoso100% (1)

- Bedouin Music of Southern SinaiDocument8 pagesBedouin Music of Southern SinaipauliNo ratings yet

- A Brief History of The AudienceDocument9 pagesA Brief History of The Audienceaccount accountNo ratings yet

- Primary Sources: A Natural History of The Artist' S Palette - The Public Domain ReviewDocument28 pagesPrimary Sources: A Natural History of The Artist' S Palette - The Public Domain ReviewmprussoNo ratings yet

- Corry Euclid MedievalsDocument71 pagesCorry Euclid MedievalsmprussoNo ratings yet

- Stearns Marsden JoyceDocument27 pagesStearns Marsden JoycemprussoNo ratings yet

- Fordham University Press Ens Rationis From Suarez To Caramuel: A Study in Scholasticism of The Baroque EraDocument3 pagesFordham University Press Ens Rationis From Suarez To Caramuel: A Study in Scholasticism of The Baroque EramprussoNo ratings yet

- Descartes Philosophical Writings 1 Pages 120 162,18 89,2Document116 pagesDescartes Philosophical Writings 1 Pages 120 162,18 89,2mprussoNo ratings yet

- Godwin Kepler HarmoniesDocument15 pagesGodwin Kepler HarmoniesmprussoNo ratings yet

- Bub GB AeeCBe1 BV8CDocument303 pagesBub GB AeeCBe1 BV8CmprussoNo ratings yet

- Sepper Descartes's ImaginationDocument186 pagesSepper Descartes's ImaginationmprussoNo ratings yet

- Fowler Hieatt SpenserDocument4 pagesFowler Hieatt SpensermprussoNo ratings yet

- A Note On The Chief Rules of Practical Conduct To Be Observed by Those Who Accept The Law of ThelemaDocument7 pagesA Note On The Chief Rules of Practical Conduct To Be Observed by Those Who Accept The Law of ThelemamprussoNo ratings yet

- Blake TaylorDocument22 pagesBlake TaylormprussoNo ratings yet

- Cohen Aquinas Sensible FormsDocument18 pagesCohen Aquinas Sensible FormsmprussoNo ratings yet

- Aristotle On Soul and BodyDocument21 pagesAristotle On Soul and BodymprussoNo ratings yet

- Sweeney Esse Primum CreatumDocument48 pagesSweeney Esse Primum CreatummprussoNo ratings yet

- Encyclopaedia of Religious KnowledgeDocument548 pagesEncyclopaedia of Religious Knowledgemprusso0% (1)

- Basic Buddhist Terms & ConceptsDocument79 pagesBasic Buddhist Terms & ConceptsmprussoNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument23 pagesPDFmprussoNo ratings yet

- 7 Point Mind Training Text Sept28Document3 pages7 Point Mind Training Text Sept28Citizen R KaneNo ratings yet

- Volume 7Document14 pagesVolume 7mprussoNo ratings yet

- Rules of Proportion in Architecture. Patrick SuppesDocument7 pagesRules of Proportion in Architecture. Patrick SuppesIsrael LealNo ratings yet

- Walker Astral BodyDocument16 pagesWalker Astral BodymprussoNo ratings yet

- Martin Lof Intuitionistic Type TheoryDocument57 pagesMartin Lof Intuitionistic Type TheorymprussoNo ratings yet

- American Academy of Arts & Sciences, The MIT Press DaedalusDocument10 pagesAmerican Academy of Arts & Sciences, The MIT Press DaedalusmprussoNo ratings yet

- Swedenborg SankaraDocument15 pagesSwedenborg SankaramprussoNo ratings yet

- A Greater and More Hidden WordDocument10 pagesA Greater and More Hidden WordmprussoNo ratings yet

- Language of Gesture in Minoan Religion by C. MorrisDocument7 pagesLanguage of Gesture in Minoan Religion by C. MorrismprussoNo ratings yet

- Psychology of The Affections in Plato and AristotleDocument21 pagesPsychology of The Affections in Plato and AristotlemprussoNo ratings yet

- 15 New York 2013 Book Fair PDFDocument96 pages15 New York 2013 Book Fair PDFmprussoNo ratings yet

- Soal Bahasa Inggris Kelas 6Document2 pagesSoal Bahasa Inggris Kelas 6mutia ambarwatiNo ratings yet

- Module Na Tunay 2 HandicraftDocument11 pagesModule Na Tunay 2 HandicraftJustina Servillon SumagpangNo ratings yet

- Issue 47Document12 pagesIssue 4712ab34cd8969100% (1)

- Elements of Visual ArtsDocument21 pagesElements of Visual ArtsAlthea Aubrey AgbayaniNo ratings yet

- Crash Course Theater and Drama 10 Mystery PlaysDocument2 pagesCrash Course Theater and Drama 10 Mystery Playscindy.humphlettNo ratings yet

- BUCIO - BH - Assignment 1Document2 pagesBUCIO - BH - Assignment 1John McwayneNo ratings yet

- 6 VR 6 FKQCFB 6 ZR 8 L 5 LT 2Document166 pages6 VR 6 FKQCFB 6 ZR 8 L 5 LT 2supreeth samuelNo ratings yet

- History of Jazz - Final - Study GuideDocument2 pagesHistory of Jazz - Final - Study Guideskyeeee123No ratings yet

- Sky Mansion - Chattarpur: S.No. Location Manufacturer Specification Tower 1Document2 pagesSky Mansion - Chattarpur: S.No. Location Manufacturer Specification Tower 1Nisha VermaNo ratings yet

- Cambridge O Level: Design & Technology 6043/12Document4 pagesCambridge O Level: Design & Technology 6043/12Ozan EffendiNo ratings yet

- Baselitz - Exhibition CatalogueDocument5 pagesBaselitz - Exhibition CatalogueArtdataNo ratings yet

- Pointers in Format Preparation For Thesis Outline/ManuscriptDocument35 pagesPointers in Format Preparation For Thesis Outline/ManuscriptRode LynNo ratings yet

- Rate 2012 CecbDocument254 pagesRate 2012 CecbChathuranga PriyasamanNo ratings yet

- Construction Materials PricesDocument58 pagesConstruction Materials Pricesruvi-coronel-3063No ratings yet

- The Role of Women in Communal Peace Resolution: A Case Study of Aristophanes' LysistrataDocument44 pagesThe Role of Women in Communal Peace Resolution: A Case Study of Aristophanes' LysistrataFaith MoneyNo ratings yet

- FIT FashionDesign PortfolioDocument7 pagesFIT FashionDesign PortfolioUday KumarNo ratings yet

- BaroqueDocument5 pagesBaroqueJeromeNo ratings yet

- Adding Unwritten: WrittenDocument1 pageAdding Unwritten: WrittenLucas ReccitelliNo ratings yet

- Cpar Q4 1Document31 pagesCpar Q4 1eyo tbzNo ratings yet

- StealingDocument15 pagesStealinggera.maahiNo ratings yet

- Presentation Skills-Unity (MBA)Document55 pagesPresentation Skills-Unity (MBA)Arash-najmaei100% (9)

- Cynthia MacDougall Knit Together Knitting EssentialsDocument21 pagesCynthia MacDougall Knit Together Knitting EssentialsLeu FreitasNo ratings yet

- Task Card Aircraft Fabric CoveringDocument9 pagesTask Card Aircraft Fabric Coveringagil5ardhya5nugrahaNo ratings yet

- The Radburn Plan 2016Document12 pagesThe Radburn Plan 2016cruxclariceNo ratings yet

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin: FALL 2020Document52 pagesThe Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin: FALL 2020Juan Carlos Montero VallejoNo ratings yet

- H.M.S. Pinafore:, T L T L ASDocument9 pagesH.M.S. Pinafore:, T L T L ASfarzadddNo ratings yet

- Evidence 2Document3 pagesEvidence 2Antonio NaelsonNo ratings yet

- ELEC. PARTS & WIRE HARNESS (FRAME) - 004 KRR19720 Serie 01913 - 02331Document8 pagesELEC. PARTS & WIRE HARNESS (FRAME) - 004 KRR19720 Serie 01913 - 02331Jose Esteem M CamelNo ratings yet