Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Health Effects of Life Transitions For

Uploaded by

Leo David KimOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Health Effects of Life Transitions For

Uploaded by

Leo David KimCopyright:

Available Formats

Public Health Nursing Vol. 26 No. 4, pp. 370379 0737-1209/r 2009 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2009.00792.

SPECIAL FEATURES: THEORY

Health Effects of Life Transitions for Women and Children: A Research Model for Public and Community Health Nursing

Margaret M. Kaiser, Katherine Laux Kaiser, and Teresa L. Barry

ABSTRACT Because maternal-child populations have traditionally been a major practice target for public and community health nursing (P/CHN), understanding the health effects of life transition experiences for women and their children is key to the advancement of P/CHN practice and research. To date there are no integrated conceptual models available that examine transition and its health effects in women, and ultimately their children, to single or multiple transitions. In order to help women and those with dependent children transition successfully, strong transition frameworks for nursing are needed. The purpose of this paper is to describe a conceptual model, Health Effects of Life Transition for Women and Children. Major components include the transition experience (developmental, situational, health illness), transition assets/risks (personal, environmental), cognitive-behavioral health indicators of transition (perception of situation, personal efcacy, change readiness, engagement, help-seeking, health behaviors, services use), transition adaptive outcomes of health (health status, intensity of need for nursing care) and competence (transition specic skill acquisition, health management, resourcefulness) and long-term preventive health outcomes (risk reduction, disability prevention, cost savings, mastery, injury prevention). The authors propose that cognitive-behavioral health indicators are foundational to a successful transition experience, are why some people have better transition outcomes than others, and when inuenced by P/CHN intervention lead to improved long-term outcomes.

Key words: health, public and community health nursing, research, transition, women.

Margaret M. Kaiser, Ph.D., P.H.C.N.S., B.C., is Assistant Professor, University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Nursing, Nebraska Medical Center,Omaha, Nebraska. Katherine Laux Kaiser, Ph.D., A.P.H.N., B.C., is Associate Professor, University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Nursing, Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, Nebraska. Teresa L. Barry, Ph.D., P.H.C.N.S., B.C., is Assistant Professor, University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Nursing, Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, Nebraska. Correspondence to: Margaret M. Kaiser, University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Nursing, 985330 Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE 68198-5330. E-mail: mkaiser@ unmc.edu 370

Life transitions can be signicant human experiences and their effects hold the potential for multidimensional health implications. Because life transitions can be life changing experiences, they offer public and community health nurses prime opportunities to intervene with women, and ultimately their dependent children, with a focus on health promotion and disease prevention, effective health management, and gaining condence and competence. Understanding the health effects of life transitions for women and their children and how to intervene is important to advance the evidence base of public and community health nursing (P/CHN) and to contribute to the prevention of adverse long-term health outcomes. Several factors contribute to the importance of scientic inquiry into the health effects of life

Kaiser et al.: Health Effects of Transition transitions for women and the inuence of these transitions on dependent children in the practice of P/CHN. Vulnerable populations such as women and their children have traditionally and consistently been priority practice populations for P/CHN practice. Because women are often family caregivers, they frequently manage the health of their families, especially their children. Therefore womens life transitions may impact child health. Public and community health nurses often encounter communitydwelling women and their children in a variety of settings in which they practice, and in the programs that they create and administer on behalf of women and children. Womens life transition experiences can affect their health status, need for nursing care, parenting behavior, and acquisition of important life skills. To date, much of the work related to life transition in women has centered around two reproductive health issues: menopause and transition to motherhood (Mercer, 1995; Woods, Mariella, & Mitchell, 2006). While this research is important, there have not been integrated conceptual or research models that have been applied to a variety of types of life transitions (e.g., launching adult children, divorce), or that have provided opportunities to examine responses to more than one transition at a time (e.g., adolescent pregnancy), a frequent reality in womens lives, especially vulnerable women. Catanzaro (1990) postulates that when multiple transitions occur simultaneously they become more complex to manage, leading to either increased health or increased illness. Schumacher and Meleis (1994) further emphasize that because of the vulnerability that results from such complexity, nurses must have strong transitional frameworks to work from to help clients transition successfully. Accounting for complexity and vulnerability are essential in order to maximize transition adaptation and intervene to reduce negative health effects, including those potential inuences on health disparities. The goals of our research program are to propose and build a conceptual and research model that (a) provides direction for the study of the health effects of womens life transitions for themselves and their dependent children, (b) facilitates testing of P/ CHN interventions for these populations, (c) contributes to evidence-based P/CHN practice, and (d) contributes to the science of preventive health outcomes.

371

Background

Denitions of transition are usually derived from two theoretical perspectives: (a) the life-span development approach, in which marker events occur and emphasis is placed on the context and process of change, and (b) the life events approach, in which disequilibrium occurs between two stable periods of time, and the emphasis is on restoration of equilibrium (Murphy, 1990). In this model, transition is dened as a passage or movement from one state, condition, or place to another, and is considered both a process and an outcome of complex person-environment interactions (Chick & Meleis, 1986). Both process and outcome are important to the development of nursing knowledge and to the practice of nursing. Schumacher and Meleis (1994) identied types of transition that are important for nursing and include developmental, situational, and health-illness transition experiences. Developmental transitions are based on stages in the life cycle (adolescence, mid-life). Situational transitions involve changes in roles or are unexpected untimely events that require adaptation (adolescent pregnancy, divorce). Health-illness transitions involve changes related to illness or health status (menopause, diabetes) (Schumacher & Meleis, 1994). Transitions are personal experiences and given the same typology, clients do not experience transitions uniformly (Chick & Meleis, 1986). Transitions are diverse and complex, may involve uncertainty, can be sequential or simultaneous, and often occur in multiples that compound the effect of transitions (Meleis, Sawyer, Im, Hilnger Messias, & Schumacher, 2000). Transitions involve a change in health status, role relations, expectations, or abilities (Chick & Meleis, 1986; Meleis, 1986). Life transitions are primarily cognitive and psychosocial experiences that are characterized by time, awareness, perception, uidity, and disruption (Kralik, Vincentin, & van Loon, 2006; Meleis, 1986). It is through cognitive, behavioral, and interpersonal processes that transitions occur (Schumacher, Jones, & Meleis, 1999). Because life transitions are often associated with actual or potential changes in health, nurses must have a comprehensive understanding of the transition process and potential health effects to intervene appropriately (Schumacher et al., 1999).

372

Public Health Nursing

Volume 26

Number 4

July/August 2009

The Conceptual Model of Health Effects of Life Transition for Women and Children

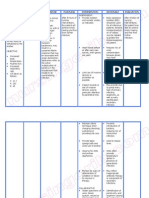

The Conceptual Model of Health Effects of Life Transition for Women and Children is depicted in Fig. 1. The large arrow at the top of the model represents the effects of life transitions on womens and childrens health at various stages and over time. Within the conceptual model (the large circle), the transition experience or type of transition (developmental, situational, health-illness) provides the context for the interaction of the three components of the model. The three components are illustrated by the smaller circles within the large circle and include (a) transition assets and risks, (b) cognitive-behavioral health indicators of transition, and (c) transition adaptive outcomes. The authors propose that the three components are interrelated where each component inter-

acts with and/or has the potential to affect other components (bidirectional arrows). The P/CHN intervention circle represents those actions that public and community health nurses take to intervene before and during transition. The major assumption underpinning the model is that P/CHN intervention, within the context of transition, is primarily psychosocial and affects the cognitive-behavioral health indicators of transition. The wavy line represents interventions directed to transition assets/risks during an urgent or crisis situation. The model in Fig. 1 was developed using Meleis et al.s (2000) transition framework as a foundation. Commonalities between Meleis et al.s (2000) model and the proposed research model are that the type of transition(s) provides the context for the experience (transition experience), personal and environmental factors are considered to either facilitate or hinder the transition experience (transition assets and risks),

Research Program Model

Health Effects of Life Transitions for Women and Children

Cognitive-Behavioral Health Indicators of Transition

Cognitive Perception of Situation Personal Efficacy Change Readiness Behavioral Engagement Help Seeking Health Behaviors Services Use

Public/Community Health Nurse Intervention

Transition Adaptive Outcomes Transition Assets/Risks

Personal Environmental Social Physical Health Health Status Intensity of Need for Care Competence Transition-Specific Skill Acquisition Health Management Resourcefulness

Preventive Health Outcomes

Transition Experience (Developmental, Situational, Health-Illness)

Research Program for M. Kaiser, K. Kaiser, T. Barry

Figure 1. Health effects of life transitions for women and children

Kaiser et al.: Health Effects of Transition and proximal or intermediate outcomes are identied (transition adaptive outcomes), which are important in assessing progress toward achievement of more long-term outcomes of health. The proposed model is different because it was developed specically for P/CHN to guide research, in particular research related to the health effects of life transitions for women and their children. Cognitivebehavioral health indicators of transition were added to this framework and are postulated to be important mutable factors that when inuenced by P/CHN intervention leads to better health outcomes. Distal outcomes resulting from P/CHN intervention during transition are conceptualized as preventive health focused.

373

situation (University of California San Francisco School of Nursing Symptom Management Faculty Group, 1994) that gives meaning to the experience (Bunting, 1988). An important inuencing factor of transition experiences is the meaning attached to the transition where meaning may facilitate or hinder adaptive transition outcomes (Meleis et al., 2000). Developing an awareness of the meaning of a transition is essential for understanding the transition experience and its health consequences (Meleis et al., 2000; Schumacher & Meleis, 1994). For example, learning about becoming a parent by attending a community parenting class is inuenced by whether or not the pregnant woman perceives the classes as important or benecial in her transition to motherhood. Personal efcacy. Perceived self-efcacy, a component of social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1997), is a judgment of ones ability to carry out a particular course of action (Pender, Murdaugh, & Parsons, 2006). It is not concerned with the skills you have, but with what you believe you can do with what skills you have under a variety of circumstances (Bandura, 1997). Efcacy judgments facilitate the undertaking of tasks that build competence and condence (Pender et al., 2006) even if faced with barriers or adverse situations. Developing condence is an indicator or desirable pattern of adaptive transition (Meleis et al., 2000). The health-illness transition of midlife women with newly diagnosed diabetes would depend in part on the womens belief or judgment in their ability to manage the chronic disease. Change readiness. Change readiness is a developmental and motivational construct that provides an explanation of how people respond to life altering events, and/or cope with life changes that are inevitable or for which they have little control (Walker, 2004). Elements of readiness for change are (a) facing uncertainty, which requires evaluation of the fear of the inevitable life change with fear of the unknown triggering readiness for change (especially in those facing a disruptive life transition such as an adolescent who becomes pregnant); (b) accepting changes in social roles or abilities, which permits people to move toward action (pregnant adolescent making appointment for prenatal care); and (c) doing whats possible about the inevitable, which means exhibiting readiness through action (pregnant adolescent attending newborn care classes; Walker, 2004). Readiness for life change is validated when the person

Transition assets and risks Transition assets and risks are personal or environmental factors that can either facilitate or hinder the transition experience. Personal factors are inherent to an individual, family, or population (e.g., obesity, race, age, mood, coping style). Environmental factors include social interactions or relationships (e.g., social support, language, literacy) and physical environmental factors (e.g., crime, transportation, walking trails; Anderson, Fielding, Fullilive, Scrimshaw, & Carande-Kulis, 2003; Evans, Barer, & Marmor, 1994; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2000; Williams, 1990). Transition assets and risks are often key elements to P/CHN assessment before and during transition. Cognitive-behavioral health indicators of transition Cognitive-behavioral health indicators of transition are sensitive to P/CHN intervention, can be changed over time, and are foundational to a successful transition experience. The authors propose that the indicators in this circle are why some people have better outcomes than others; they are the factors that when inuenced through P/CHN interventions lead to improved outcomes. The cognitive indicators are perception of the situation, personal efcacy, and change readiness. The behavioral indicators are engagement, help-seeking, health behavior, and services use.

Perception of situation. Perception is described as a conscious, cognitive process in which there is interpretation of information gathered by the senses in the context of a particular environment or

374

Public Health Nursing

Volume 26

Number 4

July/August 2009

either knows what to do or they do what they can (Walker, 2004). Engagement. Engagement is fundamental to any human interaction (Walsh, Lawless, Moss, & Allbon, 2005). How engagement is dened is highly dependent on the context in which the construct is being referred. For this model, engagement is described as the degree or level of active involvement or participation in some interaction (Carmack, 1997). People are more likely to engage with others if they can see a strong need for it, are in an environment that supports the engagement rather than hinders it, and have people to help them in the engagement (Walsh et al., 2005). At a population level, engagement would be reected in community agencies and businesses participating in the development and implementation of a plan to increase access to inuenza vaccine for uninsured or underinsured women and their children. Help-seeking. Help-seeking is generally selfinitiated with some catalyst or reason necessary for a person to begin help-seeking efforts (Boydell, Gladstone, & Volpe, 2006; Krishnan, Hilbert, & Van Leeuwen, 2001). Help-seeking is a personal choice (Cardol et al., 2005) and involves the extent to which people seek out and utilize different sources of support and resources for overcoming personal difculties (Nicholas, Oliver, Lee, & OBrien, 2004). Beliefs, perceptions, and emotions are major elements in help-seeking (Koch, 2006). Help-seeking can offer social support and coping strategies, can provide an avenue to more formal types of assistance, and can reect social problems within a persons immediate social network (Kaukinen, 2004). Help-seeking is an important means of acquiring new knowledge and skills (which can be inuenced by P/CHN intervention) in order to meet the needs of the new situation during transition (Schumacher & Meleis, 1994). A teen that becomes sexually active and talks to her friends or family about available community resources for contraceptive services is an example of help-seeking. Health behaviors. One of the most important elements that have a profound effect in peoples health and well-being is health behavior (Glanz & Maddock, 2006; USDHHS, 2000). Health behaviors are actions directed toward risk reduction and health promotion (Pender et al., 2006). Inuences that help to shape behaviors include personal choice and the

social and physical environments surrounding the individual (USDHHS, 2000). Health behavior change is sensitive to P/CHN intervention where new health behavior patterns developed in response to the transition are often part of the process of achieving adaptive transition outcomes. Midlife women often engage in the health behaviors of physical activity and healthy eating to decrease their risk of development of chronic conditions. Services use. Services use is viewed as a behavioral factor important to life transition for women and their children and includes both health services use and use of community resources. Health services use is conceptualized as behavior and refers to the actual use of formal personal health services inclusive of a variety of types (hospitals, ambulatory) and purposes (preventive, illness-related) that are either discretionary, nondiscretionary, or mixed in their nature (Andersen, 1968, 1995). During life transition experiences, women often need and seek out health and community services for themselves (e.g., divorce support groups) and their children (e.g., immunization clinics). Connecting women and children to health and community services is an evidence-based P/CHN intervention (Keller, Strohschein, Lia-Hoagberg, & Schaffer, 2004).

Transition adaptive outcomes Transition adaptive outcomes are conceptualized as positive and are the intended result(s) that occurs from P/CHN intervention during life transitions. These outcomes are measurable health and/or health-related effects of the transition experience. The authors propose that a successful or adaptive transition can be supported by P/CHN intervention and leads to the intermediate or proximal outcomes of health and competence. Health is dened as the state of complete physical, mental and social wellbeing and not merely the absence of disease and inrmity (World Health Organization, 1948). Competence is a set of skills that enables a person to function effectively (Jones, 2004) and is dened in terms of specic domains of achievement or success (e.g., social competence; Masten & Coatsworth, 1998). The model indicators of health adaptive outcomes include health status and intensity of need for care. Indicators of competence include transition-specic skill acquisition, health management, and resourcefulness.

Kaiser et al.: Health Effects of Transition Health status. Health status is viewed as a health outcome of the transition experience that includes well-being and functioning and is conceptualized as multifaceted, global, and changing over time (Evans et al., 1994; Feinstein, 1993). Differences in health status can be associated with behavior, resources, life-span experiences, health care service availability, and utilization patterns (Feinstein, 1993). Health status can be evaluated by objective (e.g., blood pressure, BMI, Hemoglobin A1C) and subjective measures (e.g., self-reported health status). Intensity of need for care. Intensity of health need is considered the magnitude or extent of need in health or health-related human domains. Health need inherently considers the clients holistic subjective evaluation of their personal situation in combination with the public and community health nurses evaluation of unmet needs (including health promotion), assets, risks, and problems (Andersen, 1968, 1995; D. A. Peters, personal communication, July 18, 2007). Intensity of need for care has been shown to be sensitive to change over time (Hays, Kaiser, McMahon, & Kaup, 2000), and has been used as an outcome measure (Kaiser, Hays, Miller, & Nelson, 1999). Lowincome families with dependent children who are homeless face higher levels of intensity of need for care than do married middle-income families with adequate nancial resources. Transition-specic skill acquisition. In the practice of P/CHN, the acquisition of skill is tied to improving client capacity for self-direction and independence in health care matters, including health promotion. The proposed model considers selected skill acquisition, specically related to the type of life transition occurring, as an important transition adaptive outcome. Because skill acquisition can be measured over time (Slade, Holloway, & Kuipers, 2003), it is a good outcome to consider in evaluating the effect of P/CHN intervention on the health and competence of women and their children as they experience life transitions. Examples of skills that can be acquired are parenting, types of physical activity regimens, healthy cooking, or coping. Health management. Health management is a unique and crucial set of preventive and illness-related health skills related to personal health status and health needs that assists persons to be producers of health, rather than only consumers of health (Harris & Guten,

375

1979; Peterson & Kane, 1997). While both health and management are common words, their use together holds meaning that represents a major practice effort for P/CHN. Peters (1999) described health management from a P/CHN perspective as the clients management of health status, including a measure of involvement or engagement, technical abilities, and adherence to prescribed therapeutic regimens. Women generally have the majority of the health management responsibility in a family, regardless of structure. This inuence most likely affects their childrens future health-seeking (Friedman & Lahad, 2007). Health management skills can include managing minor childhood illnesses, asthma self-management, and obtaining preventive dental care. Resourcefulness. Resourcefulness refers to a learned cognitive-behavioral repertoire of skills and strategies used to successfully deal with problems or stressful life events (Meichenbaum, 1977; Rachman, 1978). Resourcefulness depends on cognitive skills used to accurately perceive the situation, efcacy to cope with the situation, and readiness to deal with change (Rosenbaum, 1990). Learned resourcefulness is particularly important when coping with and adapting to novel situations (Rachman, 1978) such as transitions. According to Zerwekh (1992), building client strength, a way of becoming more resourceful, is one of the key interventions of P/CHN. Resourcefulness can be seen in women who use or start self-help groups or organize child-care cooperatives with their neighborhoods.

Public and community health nursing intervention Public and community health nursing intervention includes actions taken by nurses on behalf of communities and the individuals/families living in them (Keller et al., 2004). The desired client transition adaptive outcomes result from interventions targeted to the cognitive and behavioral domains, except during crisis such as domestic violence or child abuse (wavy line in Fig. 1), which require immediate P/CHN intervention. Public and community health nursing scholarship, and the resulting evidence for intervention and systems of knowledge, has strong practice ties to several standardized nursing languages and intervention schemes such as the Omaha System (Martin, 2005), the Intervention Wheel (Keller et al., 2004), and the Clinical Care Classication System (Saba, 2002).

376

Public Health Nursing

Volume 26

Number 4

July/August 2009

Because of these existing knowledge systems, P/CHN intervention is conceptualized broadly in the model. It is the perspective of the authors that there are adequate P/CHN interventions conceptualized and developed, but inadequate testing of the effectiveness of P/CHN interventions. Therefore, one of the basic premises of the model is the conscious intent to use existing P/CHN intervention systems. The selection of the intervention and system to be used will be matched to the transition experience (context), the desired outcome(s), and the population under study.

Preventive health outcomes Preventive health outcomes are conceptualized as positive long-term results stemming from adaptive transition intermediate outcomes that have been affected by P/CHN intervention during life transitions. These long-term or distal outcomes are measurable markers of preventive health including risk reduction, disability prevention, cost savings, mastery, and injury prevention as examples.

ness (transition adaptive outcome of competence) for the adolescent mothers. A cross-sectional quasiexperimental design is planned to determine the effectiveness of the parenting program (P/CHN interventions of health teaching and counseling) in developing resourcefulness in rst time pregnant and parenting middle adolescent mothers 1518 years of age (personal transition risks). A comparison of the cognitive skills of perception, personal efcacy, and change readiness (cognitive-behavioral health indicators of transition) that inuence resourcefulness and the improvement of resourcefulness skills (transition adaptive outcome of competence) will be assessed pre- and postintervention. Long-term or preventive health outcomes would include decreased incidence of child abuse and neglect (injury prevention).

The Research Model Applied

The Conceptual Model of Health Effects of Life Transition for Women and Children was developed for P/CHN to guide research, specically research related to the health effects of life transitions for women and their children at various stages and over time. Because life transitions are often associated with actual or potential changes in health (Schumacher et al., 1999), the use of the model will facilitate P/CHN understanding of the potential health effects of transitions for women and their children, and facilitate public and community health nurses to intervene appropriately. To illustrate how the model can be used in research, three examples of research studies related to the authors program of research are provided. These studies are either in process or under development.

Exemplar 2 A study is designed to improve the health management skills of low-income young adult (2025 years) mothers with one or more children who use Headstart programs in under-privileged neighborhoods (social environment risk). A longitudinal quasi-experimental design, over 3 years will be used to assess the preintervention and postintervention child health management skills of the women in the intervention group and also in a control group. The intervention consists of a targeted parent health management outreach and case management group intervention (Keller et al., 2004) provided at the Headstart program regarding how to manage your childs health using the medical home concept. Transition adaptive outcomes will include measures of health management skills (competence). Long-term or preventive health outcomes will include adequacy of immunization status for the children and mothers and assessment of health-seeking for preventive health (risk reduction). Exemplar 3 A state public health department is concerned about increasing levels of obesity (personal risk) and lack of physical activity (health behaviors) among periomenopausal women in the state based on the ongoing Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Behavioral Risk Factor Survey completed by the state (CDC, 2008). The department views this as a transition that warrants attention and wants to do a 4-year pilot study aimed at improving the health status and physical activity skills of the population of periomenopausal women in their state. An environmental survey

Exemplar 1 The P/CHN has been providing parenting classes to rst-time pregnant and parenting adolescents (developmental and situational transition experiences). The parenting program is based on developing resourcefulness in the adolescent mothers because resourcefulness helps one to deal with problems and stressful life events regardless of the context of the situation. The P/CHN wants to know how effective her parenting program is in developing resourceful-

Kaiser et al.: Health Effects of Transition of the states communities shows many fast food restaurants and bars but limited availability of inexpensive physical environmental assets such as walking or biking trails, parks, or community centers with no/low cost exercise equipment for public use. Two local public health departments have been working with a group of community leaders who have identied obesity and physical activity as areas of interest. A coalition-building, community organizing, social marketing (Keller et al., 2004) intervention is planned to mobilize the community and local businesses, increase awareness of the problem, engage the community in enhancing the facilities available for physical activity, and provide education designed to help periomenopausal women acquire skills to increase their physical activity. Transition adaptive outcomes include measures of self-reported health status and physical activity levels in the women. Long-term or preventive health outcomes will include assessment of yearly BMI, chronic disease development, and tracking improvement in number of physical acitivity resources and programs (risk reduction and disability prevention).

377

Future Work

The authors believe that the development of this conceptual and research model is needed to build the science and evidence base for P/CHN, especially for maternal-child populations. Understanding the health effects of life transition experiences for women and transition effects on children will advance P/CHN practice and research, and holds the potential to impact health policy for these populations. Future work related to this model will focus on building and testing the linkages between the model components, testing the type of effect(s) (mediating or moderating) of P/ CHN intervention, and evaluating the intermediate outcomes and the effectiveness of P/CHN intervention. In addition, evaluating the distal outcomes in longitudinal studies would be important to validate the contribution of P/CHN intervention to the health care system and to reducing health disparities in the vulnerable populations that public and community health nurses frequently care for.

References

Andersen, R. M. (1968). A behavioral model of families use of health services (Research series 25).

Chicago, IL: Center for Health Administration Studies, University of Chicago. Andersen, R. M. (1995). Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: Does it matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 36(1), 110. Anderson, L. M., Fielding, J. E., Fullilive, M. T., Scrimshaw, S. C., & Carande-Kulis, V. G. (2003). Providing affordable family housing and reducing residential segregation by income. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 24(3S), 2531. Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efcacy: The exercise of control. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company. Boydell, K. M., Gladstone, B. M., & Volpe, T. (2006). Understanding help-seeking delay in the prodrome to rst episode psychosis: A secondary analysis of the perspective of young people. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 30(1), 5460. Bunting, S. M. (1988). The concept of perception in selected nursing theories. Nursing Science Quarterly, 1, 168174. Cardol, M., Groenewegen, P. P., deBakker, D. H., Spreeuwenberg, L., vanDijk, L., & vandenBosch, W. (2005). Shared help-seeking behavior within families: A retrospective cohort study. British Medical Journal, 330(7496), 882884. Carmack, B. J. (1997). Balancing engagement and detachment in caregiving. Image: Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 29(2), 139143. Catanzaro, M. (1990). Transitions in midlife adults with long-term illness. Holistic Nursing Practice, 4(3), 6573. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]. (2008). Behavioral risk factor surveillance system survey questionnaire. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chick, N., & Meleis, A. I. (1986). Transitions: A nursing concern. In P. L. Chinn (Ed.), Nursing research methodology: Issues and implementation (pp. 237257). Rockville, MD: Aspen. Evans, R. G., Barer, M. L., & Marmor, T. R. (Eds.). (1994). Why are some people healthy and others not? The determinants of health of populations. New York: Walter de Gruyter. Feinstein, J. S. (1993). The relationship between socioeconomic status and health: A review of the literature. The Milbank Quarterly, 71, 279322. Friedman, A., & Lahad, A. (2007). Association between maternal and adult offspring utilization

378

Public Health Nursing

Volume 26

Number 4

July/August 2009

of primary healthcare. Israel Medical Association Journal, 9(2), 8689. Glanz, K., & Maddock, J. (2006). Behavior, health related. Retrieved on May 11, 2008, from http:// www.enotes.com/public-health-encyclopedia/ behavior-health-related Harris, D. M., & Guten, S. (1979). Health protective behavior: An exploratory study. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 20(1), 1729. Hays, B. J., Kaiser, K. L., McMahon, C. E., & Kaup, K. L. (2000). Public health nursing data: Building the knowledge base for high-risk prenatal clients. MCN: The American Journal of Maternal Child Nursing, 25(3), 151158. Jones, L. V. (2004). Enhancing psychosocial competence among Black women in college. Social Work, 49(1), 7584. Kaiser, K. L., Hays, B. J., Miller, L. L., & Nelson, F. (1999). Patterns of health resource utilization, costs, and intensity of need for primary care clients receiving public health nursing case management. Nursing Case Management, 4(2), 5361. Kaukinen, C. (2004). The help-seeking strategies of female violent-crime victims. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 19(9), 967990. Keller, L. O., Strohschein, S., Lia-Hoagberg, M. A., & Schaffer, B. (2004). Population-based public health nursing interventions: Practice-Based and evidence-supported. Part I. Public Health Nursing, 21(5), 453468. Koch, L. H. (2006). Help-seeking behaviors of women with urinary incontinence: An integrative literature review. Journal of Midwifery and Womens Health, 51(6), e39e44. Kralik, D., Vincentin, K., & van Loon, A. (2006). Transition: A literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 55(3), 320329. Krishnan, S. P., Hilbert, J. C., & Van Leeuwen, D. (2001). Domestic violence and help-seeking behaviors among rural women: Results from a shelter-based study. Family and Community Health, 24(1), 2838. Martin, K. S. (2005). The Omaha System: A key to practice, documentation, and information management (2nd ed.). St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. Masten, A. S., & Coatsworth, J. D. (1998). The development of competence in favorable and unfavorable environments. American Psychologist, 53(2), 205220. Meichenbaum, D. (1977). Cognitive-behavior modication: An integrative approach. New York: Plenum Press. Meleis, A. I. (1986). Theory development and domain concepts. In P. Moccia (Ed.), New approaches

to theory development (pp. 321). New York: National League for Nursing. Meleis, A. I., Sawyer, L. M., Im, E., Hilnger Messias, D. K., & Schumacher, K. (2000). Experiencing transitions: An emerging middle-range theory. Advances in Nursing Science, 23(1), 1228. Mercer, R. T. (1995). Becoming a mother: Research on maternal identity from Rubin to the present. New York: Springer Publishing Company. Murphy, S. A. (1990). Human responses to transitions: A holistic nursing perspective. Holistic Nursing Practice, 4(3), 17. Nicholas, J., Oliver, K., Lee, K., & OBrien, M. (2004). Help-seeking behavior and the Internet: An investigation among Australian adolescents. Australian e-Journal for the Advancement of Mental Health, 3(1), 18. Pender, N. J., Murdaugh, C. L., & Parsons, M. A. (2006). Health promotion in nursing practice (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall. Peters, D. A. (1999). Home care documentation. In P. W. Iyer, & N. H. Camp (Eds.), Nursing documentation: A nursing process approach (3rd ed., pp. 304318). St. Louis, MO: Mosby. Peterson, K. W., & Kane, D. P. (1997). Beyond disease management: Population-based health management. In W. E. Todd, & D. Nash (Eds.), Disease management: A systems approach to improving patient outcomes (pp. 305346). Chicago: American Hospital Publishing Inc. Rachman, S. (1978). Fear and courage. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman and Company. Rosenbaum, M. (Ed.) (1990). Learned resourcefulness: On coping skills, self-control, and adaptive behavior. New York: Springer Publishing Company. Saba, V. (2002). Nursing classications: Home health care classication system (HHCC): An overview. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 7(3). Retrieved on July 1, 2008, from http:// www.nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategories/ ANAMarketplace/ANAPeriodicals/OJIN/Tab leofContents/Vol31998/Vol3No21998/HHCC AnOverview.aspx. Schumacher, K. L., Jones, P. S., & Meleis, A. I. (1999). Helping elderly persons in transition: A framework for research and practice. In E. Swanson, & T. Tripp-Reimer (Eds.), Life transitions in the older adult: Issues for nurses and other health professionals (pp. 126). New York: Springer Publishing Company Inc. Schumacher, K. L., & Meleis, A. I. (1994). Transitions: A central concept in nursing. Image: Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 26(2), 119127.

Kaiser et al.: Health Effects of Transition Slade, M., Holloway, F., & Kuipers, E. (2003). Skills development and family interventions in early psychosis service. Journal of Mental Health, 12(4), 405415. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS]. (2000). Healthy people 2010. 2nd ed. With understanding and improving health and objectives for improving health (Vol. 2). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Ofce. University of California San Francisco School of Nursing Symptom Management Faculty Group. (1994). A model for symptom management. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 26, 272276. Walker, C. A. (2004). Change readiness: A construct to explain health and life transitions. Journal of Theory Construction and Testing, 8(1), 2633. Walsh, K., Lawless, J., Moss, C., & Allbon, C. (2005). The development of an engagement tool for practice development. Practice Development in Health Care, 4(3), 124130.

379

Williams, D. R. (1990). Socioeconomic differentials in health: A review and redirection. Social Psychology Quarterly, 53(2), 8189. Woods, N. F., Mariella, A., & Mitchell, E. S. (2006). Depressed mood symptoms during menopausal transition: Observations for the Seattle Midlife Womens Health Study. Climacteric: Journal of the International Menopausal Society, 9(3), 195203. World Health Organization. (1948). Preamble to the constitution of the World Health Organization as adopted by the International Health Conference, New York, June 1922, 1946; signed on July 22, 1946, by the representatives of 61 states (Ofcial Records of the World Health Organization, no. 2, p. 100) and entered into force on April 7, 1948. Zerwekh, J. (1992). Laying the groundwork for family self-help: Locating families, building trust, and building strength. Public Health Nursing, 9, 1521.

You might also like

- Nur CDDocument4 pagesNur CDLeo David KimNo ratings yet

- NCP CKD MEdSurgWardDocument2 pagesNCP CKD MEdSurgWardLeo David KimNo ratings yet

- Stages of HypertensionDocument3 pagesStages of HypertensionLeo David KimNo ratings yet

- Nursing Care Plan Neonatal SepsisDocument2 pagesNursing Care Plan Neonatal Sepsisderic100% (20)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Intellectual DisabilityDocument42 pagesIntellectual Disabilityarbyjames86% (7)

- Training Book On Multiple DisabilityDocument81 pagesTraining Book On Multiple DisabilityMina Agarwal100% (2)

- ABAS JournalTestReviewDocument7 pagesABAS JournalTestReviewPramita Fridia NNo ratings yet

- Journal of Music TherapyDocument88 pagesJournal of Music TherapySafa SolatiNo ratings yet

- Lists of Assessment Tools Used in Pediatric Physical TherapyDocument17 pagesLists of Assessment Tools Used in Pediatric Physical TherapyRusu Ciprian0% (1)

- Intellectual and Developmental DisabilitiesDocument3 pagesIntellectual and Developmental Disabilitiesapi-300880250No ratings yet

- Effects of A Model Treatment Approach On AdultsDocument10 pagesEffects of A Model Treatment Approach On AdultsAnaLaura JulcahuancaNo ratings yet

- Perfoma For Registration of Subject For DissertationDocument21 pagesPerfoma For Registration of Subject For DissertationgopscharanNo ratings yet

- 4 Culture in Moral BehaviorDocument58 pages4 Culture in Moral BehaviorMartha Glorie Manalo WallisNo ratings yet

- Art As Therapy Collected Papers (2000) - Edith Kramer PDFDocument273 pagesArt As Therapy Collected Papers (2000) - Edith Kramer PDFsamuel rc100% (3)

- Matson, J.L. (Ed.) (2009) - Social Behavior and Skills in Children. NY, USA. Springer.Document332 pagesMatson, J.L. (Ed.) (2009) - Social Behavior and Skills in Children. NY, USA. Springer.Steven Sigüenza100% (1)

- Intellectual Disabilities Fact SheetDocument4 pagesIntellectual Disabilities Fact SheetNational Dissemination Center for Children with DisabilitiesNo ratings yet

- Manual On Developing Communication SkillsDocument354 pagesManual On Developing Communication SkillsMadhu sudarshan ReddyNo ratings yet

- Is Perfectionism Good, Bad, or BothDocument13 pagesIs Perfectionism Good, Bad, or BothPolarisNo ratings yet

- Research Plan ProposalDocument11 pagesResearch Plan ProposalsweetiramNo ratings yet

- Intellectual Disabilities ScriptDocument6 pagesIntellectual Disabilities Scriptapi-302509341No ratings yet

- SB 12-159 - Services For Children With Autism Under Medicaid Waiver ProgramDocument2 pagesSB 12-159 - Services For Children With Autism Under Medicaid Waiver ProgramSenator Mike JohnstonNo ratings yet

- 2nd Testing of The Mentally Retarded PopulationDocument20 pages2nd Testing of The Mentally Retarded PopulationHoorya HashmiNo ratings yet

- 1.ABAS - II - Sample Report - ShortDocument6 pages1.ABAS - II - Sample Report - ShortMateiNo ratings yet

- ABAS3 Score Report ExamplesDocument16 pagesABAS3 Score Report ExamplesAllana LimaNo ratings yet

- Understanding Social Sciences and Applied DisciplinesDocument57 pagesUnderstanding Social Sciences and Applied DisciplinesJenalin MakipigNo ratings yet

- Emotional Intelligence in Project ManagementDocument16 pagesEmotional Intelligence in Project ManagementJaved IqbalNo ratings yet

- Young Children's Biological Predisposition To Learn in Privileged DomainDocument6 pagesYoung Children's Biological Predisposition To Learn in Privileged DomainVeronica Dadal0% (1)

- Assessing Adaptive Behavior in Young ChildrenDocument34 pagesAssessing Adaptive Behavior in Young Childrenlia luthfiahNo ratings yet

- IndexDocument12 pagesIndexletinonsideNo ratings yet

- Cognitive-Behavioral Play Therapy For Preschoolers: Integrating Play and Cognitive-Behavioral InterventionsDocument22 pagesCognitive-Behavioral Play Therapy For Preschoolers: Integrating Play and Cognitive-Behavioral InterventionsvalfgeNo ratings yet

- Intellectual Disability: Definition, Classification, Causes and CharacteristicsDocument12 pagesIntellectual Disability: Definition, Classification, Causes and CharacteristicsRyan RV ViloriaNo ratings yet

- Mental Disorders and DisabilitiesDocument395 pagesMental Disorders and DisabilitiesDR DAN PEZZULONo ratings yet

- VinelandDocument35 pagesVinelandHajra KhanNo ratings yet

- Systematic Adaptive Behavior Checklist Ages 6-13Document4 pagesSystematic Adaptive Behavior Checklist Ages 6-13loie anthony nudaloNo ratings yet