Professional Documents

Culture Documents

SULS Mooting Manual

Uploaded by

Zacharia BrucknerOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

SULS Mooting Manual

Uploaded by

Zacharia BrucknerCopyright:

Available Formats

Sydney University Law Society Mooting Manual

By Suzannah Morris and Odette Murray

*

Manual is somewhat of a misnomer for this document. There is no one way to moot. This document is merely a reflection of our experience of participating in and coaching teams in both internal and inter-varsity competitions.

Receiving the problem Q

Researching the Q and formulating an argument

Preparing Written Submissions

Delivering your oral submissions

Preparing Oral Submissions

Receiving your opponents submissions

Receiving Feedback from the Judge/s

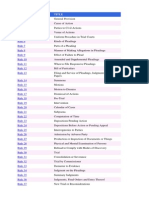

What is a Moot? Why should I do it?...................................................... 4 Who will judge a Moot?.......................................................................... 4 How is a Moot judged? ........................................................................... 4 Receiving and researching the problem question .................................. 5 How do I start my research?................................................................. 5 Developing a case theory ..................................................................... 6 Thinking holistically .............................................................................. 6 Structuring submissions to persuade ................................................... 7 Preparing written submissions ............................................................... 7 Written submissions as an aid for the Court during your oral submissions.......................................................................................... 7 Drafting written submissions................................................................ 7 What to do after receiving your opponents written submissions?... 8 Preparing oral submissions..................................................................... 8 How to structure oral submissions ....................................................... 8 Introducing your case ....................................................................... 9 Conclusion.......................................................................................... 11 Rebuttal and sur-rebuttal................................................................... 11 Delivering your oral submissions before judge/s ................................. 12 Answering Questions ......................................................................... 12 Developing good advocacy technique ................................................ 14 Case Citation ................................................................................... 16 Public International Law Moots (Distinguishing Features)................... 16

What is a Moot? Why should I do it?

According to Wikipedia, a moot originated in Anglo Saxon times and involved a gathering of prominent men in a locality to discuss matters of local importance. Today, however, mooting is a legal hearing modeled on an appeal from a trial. As such, all of the facts have been agreed upon and there are no witnesses. What is at issue is the way in which the law has been applied to the facts and this is argued out before a judge or a panel of judges. The closest approximation to a moot in real life, in terms of form and style, is an application for special leave to appeal before the High Court, where counsel has only 20 minutes to convince the court of their case whilst being peppered by questions. Mooting is a rewarding co-curricular activity. It provides opportunities to develop instinctive legal reasoning which can aid your future legal studies. Further, it provides a chance to learn advocacy techniques, become more confident with the law and can actually be a lot of fun.

Who will judge a Moot?

The preliminary rounds of the competition will be judged by students with mooting experience themselves. The mooting competitions at Sydney University do not require or expect participants to have any previous experience, and in these rounds newcomers can feel at ease. The benches judging the semi-finals and finals usually consist of three professionals. The semi-finals are judged by solicitors, barristers and academics. The benches for the finals are normally presided over by a Judge of the Supreme Court, Federal Court or High Court.

How is a Moot judged?

Apart from the judgment in law, which will favour one team ahead of another, mooters are judged individually in three board areas. A winner is determined based on the moot performance, not an evaluation of who won on the law. The general areas include: Legal research and content of argument Presentation: including court etiquette Question answering skills

Receiving and researching the problem question

Begin with the facts. Think of how all the facts tie together. It may be helpful to develop a chronology or flow chart (or diagram, or map) to illustrate the facts of the moot question. Once you have identified the pertinent facts, think about which facts are more persuasive for each side and how these facts might be used in a legal argument. The first part of preparation for a moot is not unlike preparing for a tutorial problem question in any of the law subjects you have been studying. It is necessary for you to identify all the legal issues arising from the question, taking care to ensure you identify which of the issues are your responsibility (depending upon which of the positions junior or senior counsel - has been allocated to you). How do I start my research? Effective research involves several key steps. The time and effort required at each stage will vary according to the particular nuances of your moot question. Step 1 The starting point of your research involves identifying what law you are applying. It may be obvious in a Torts Moot but not so obvious if you are involved in an arbitration moot. Step 2 Having identified what field of law the problem is based on, now is the time to formulate a hypothesis as to what you think the answer is to the legal issues you have identified. You can use this hypothesis your hunch, as it were to guide your research. Dont just open up a Contracts Law textbook at Chapter 1 and start reading use the hypothesis to help narrow your research. Dont be afraid to change or refine the hypothesis as your research develops. Step 3 In internal moots you may not have as much preparation time as the moot question demands. The key is making your research comprehensive but doing so in an efficient and effective manner. Some useful tips are: Let the problem guide your research. Often in internal moots there will be references to case law or statutes in the problem question. These are a great starting point for your research. Be aware of the status of the authorities you are relying on o Statutes and decisions of superior courts bind whereas decisions of other courts are persuasive. Secondary sources (articles and texts) are illustrative and give persuasive guidance, but no more. It is important to note that the status of authorities will also depend on the jurisdiction. For example, there is no doctrine of precedent in the

International Court of Justice but there is in the New South Wales Supreme Court. Follow up footnotes in cases/texts/articles you always want to read the original cases for yourself, and not rely on someone elses assessment or summary of them. Dont let the minutiae distract you from the big picture make sure you are familiar with the general principles of the area of law at issue eg, dont fail to have authorities on duty of care to hand, just because the only question in dispute relates to breach of duty, since a Judge may still want to ask a question on duty of care.

Developing a case theory Ask yourself, what do I need to prove to get the relief my client seeks? To have a case theory is to understand your complete case. It involves understanding how all the puzzle pieces of your case fit together to make the winning picture. To develop a case theory it is essential that you consider questions such as: Must I prove all 4 elements of the test to succeed? Do I have a partial or complete defence? Do Junior Counsels submissions rely on the success of Senior Counsel or does Junior Counsel submit in the alternative? What is necessary? What is sufficient? It is essential that you look out for any traps, that is, any inconsistencies or reverse burdens that may arise on the facts. To navigate these traps ensure that you are aware of your co-counsels arguments. Further, always consider what the standard of proof is and who bears the burden of proof. Having a case theory also involves understanding the reason why your argument is the better argument. Thinking holistically When preparing your submissions, dont close your mind to what everyone else in the moot is researching. It is important you think holistically in preparation for any moot. Appreciating all angles of the case will make you better on your allocated issues. Awareness of your opponents case will (a) encourage you to acquire more knowledge about the relevant area of law; (b) force you to improve your case to combat the key points of the opponents case; and (c) make you better at responding (both to their submissions and to questions from the bench).

Structuring submissions to persuade When planning your submissions it is important to consider the order of your submissions and to make sure they are ordered in the most persuasive way. In general, strongest submissions are argued first. This shows you putting your best foot forward, both in the law and as an advocate. In certain circumstances, however, this rule can be broken. For example, if it would be more logical to put forward a weaker submission X (say, on jurisdiction or standing) before a stronger submission Y (merits), then you should do so. Consider also whether to lead complete defences before partial defences.

Preparing written submissions

Written submissions as an aid for the Court during your oral submissions Written submissions in internal competitions are intended to give the judge a concise and precise overview of your case. Often they are read only briefly by the Judge and as such it is important to make them clear and succinct. Written submissions should essentialise your case, and help orient the judge if they get lost in the middle of your submissions. Written submissions may only be read briefly but this does not diminish their importance. The submissions constitute a work of substantive legal research and reasoning. It is essential that they correct; address the issues; cite authorities; and, progress in a locally reasoned order. For any kind of written submissions, makes sure you know the RULES eg as to length, formatting, etc. Exceeding word limits or failing to cite authorities correctly can lead to an avoidable deduction of marks, and to hand up additional material to the judge is often disallowed. Drafting written submissions A submission is a because sentence. It always seeks to achieve a desired outcome by reference to (or because of) a posited argument. One can conceptualise it as having 3 parts: (1) the proposition; (2) the because; and (3) the argument. For example, a submission in a criminal law moot might be: The Appellant is not guilty of the offence of homicide because, in striking the deceased, she acted in selfdefence. When citing authorities in support of a submission it is important to use reported citations were possible before the medium neutral citation (that is, citations from reported series, such as CLR, FCR, ALR, before medium neutral citations such as FCA

or HCA). Further, pinpoint citations should be used where appropriate (but double check you give the correct pinpoint). Submissions should not overlap with one another (as that means there is some redundancy in at least one of the submissions), nor should they leave any gaps (they should comprehensively address all of the permutations of your case theory). What to do after receiving your opponents written submissions? Upon receipt of your opponents written submissions, it is important to read them carefully and make sure you understand the arguments/authorities on which they purport to rely. If the submissions raise cases or principles that you are not familiar with, research them and incorporate these into your submissions where you think this is necessary. Alter your submissions to take account of and rebut any points in the written submissions which you think are detrimental to your case. Do not run away from a good argument put against you (leaving it unchallenged is the worst thing you can do!); rather, hone in on its flaws and put the best case you can against it. In internal moots, you only get your opponents written submissions a moment before the moot starts. In these circumstances, the document is more of an overview or aid, so dont panic too much about what is in them. It is important to note that in intervarsity competitions, where there is a considerable lapse of time between written and oral rounds, mooters are not generally bound by their written submissions.

Preparing oral submissions

How to structure oral submissions In broad terms, oral submissions have 5 parts (not all of which are strictly required): (1) appearances; (2) introduction; (3) outline of submissions; (4) submissions; (5) conclusion. Different role of counsel in a moot 1. Senior Appellant (SA): presents all 5 parts give appearances, introduces the case, gives an outline of both SA/JA subs, presents their own submissions, concludes their own submissions and then hands over to JA.

2. Junior Appellant (JA): Parts 3, 4 and 5 only. In closing, the JA will need to deal with relief sought. 3. Senior Respondent (SR): Presents all 5 parts gives appearance, introduces the respondent case, ,outlines SR/JR subs, presents their own submissions. The SR must also shift the perspective to the respondent case, by being responsive to the SAs arguments; and then hand over to JR. 4. Junior Respondent (JR): Parts 3, 4 and 5 only. The JR must also be responsive, and deal with relief sought. Giving appearances This is the way you introduce yourself to the Court at the very beginning of the moot. The judge will call for appearances, and then the SA, followed by the SR, will introduce themselves and junior counsel. This is an opportunity to make a good first impression. Be confident. Appearances have three elements: 1. Names of Counsel 2. Names of Party that counsel is representing 3. Time allocated to each speaker For example: May it please the Court, my name is Ms Morris and I am joined by Ms Murray on behalf of the appellant in this matter, Ms Ambo. I will be speaking for 20 minutes and Ms Murray for a further 20 minutes. Each Senior is responsible for giving the appearances - it is not done individually. Introducing your case Some mooters like to give a brief thematic overview at the start of their oral submissions. Such an introduction is used to get the judge to see the case from their perspective, rather than just a jumble of facts and law. If you choose to use such an introduction (note that it is not strictly necessary and may take up valuable minutes) it is important that it is both brief and persuasive (but not unduly emotional). An example of such an introduction is: This case concerns the conflict between a states right to protect itself against violent attacks and its obligations towards others on the international plane. Outlining your submissions o You should always outline your submissions before you make them.

o An outline is a quick summary of what you will submit before you submit it o It has 5 components: 1. Signal what your submissions will address (in relation to the second ground of appeal); 2. say how many submissions you will make ( we have two submissions); 3. state the proposition (We submit that there is no duty of care to Angela Ambo ); 4. state the first submission ( because, first, XXX); 5. state the second submission (Secondly, and in the alternative, we submit there is no duty of care because XXX) o This method is nicknamed across before down, because you cover at a surface level everything you are going to say (ie go across) before diving into the depths of individual arguments (ie go down). Signposting When delivering your submissions it is important that you use appropriate signposting. Generally, when delivering a submission the following order should be followed: 1. Restate your submission o signal that you are now turning to address your first submission, and restate it succinctly o You may not need to restate it all if you can develop a short hand way of referring to the submission use that: eg: I turn now to our first submission, which is that no duty of care exists. 2. Outline any sub-submissions o It is possible that each submission you make will need to be broken down into several parts. For example, a submission that says A hitting B did not cause Bs death might be broken down into two sub-submissions dealing with (i) intervening acts which break the chain of causation and (ii) remoteness of damage. o If you do wish to make sub-submissions, you should outline them before making them. Use the same formula as above. 3. Make the submission o You are (only) now ready to start making your prepared substantive submissions. This is where you will need to exercise your legal reasoning skills. Every proposition you make should be supported by authority. Do not leave out a single step in the reasoning process, no matter what argument you are putting to the judge. The key to good submissions is persuasion. o That means continually flagging for the court what you are saying, and what kind of point you are making:

10

The authorities are divided, your honour. If we look to the case of X we see thatby contrast, your honour, the reasoning in. The respondent submits that the approach of Deane J is to be preferred for 2 reasons Contrary to what the applicant submitted, there is no right of self defence against non-state actors We differ from the plaintiff in one crucial respect: whether the duty of care was in fact owed The threshold issue, your honour, is whether the applicant has standing to bring this claim

Such phrases flag for the judge why it is you are submitting what you are submitting. It is important that you structure your submissions so they are tight. That is, each sentence should lead seamlessly into your next sentence, so there are no holes in your argument there are no questions left begging. A extremely experienced mooter is able to structure their submissions in such way that a judge will only ask the questions which the mooter wants to be asked, and only at the point in the submissions when the mooter wants be asked. Conclusion At the end of the submissions, you should conclude appropriately. This may be simply by handing over to your co-counsel, saying May it please the Court, those are my submissions, I defer to my Junior counsel to continue the case for the appellant; or, if you are junior counsel, saying May it please the Court, those are the submissions of the appellant, or by stating what relief you seek. Always conclude in one way or another, even if time is scarce. Sitting down mid-sentence does not leave a good impression. Rebuttal and sur-rebuttal Rebuttal is the right of the appellant to respond to the submissions made by the respondent. Sur-rebuttal is the right of the respondent to respond to only those submissions made by the appellant during rebuttal. Internal mooting competitions do not have rebuttal and sur-rebuttal, but many intervarsity competitions do.

11

Delivering your oral submissions before judge/s

Judges should always be addressed as Your Honour. When there is more than one judge sitting on the bench, they are referred to collectively as the Court, unless one judge has asked you a question and you are answering her/his question. Generally you use the term your honour instead of you. Questions from the Bench are one of the most important aspects of mooting and are to be welcomed, not regarded as impediments or interruptions. They test the strength of argument, familiarity with the facts and with the law. They provide a chance for mooters to show how clever they really are. In the unfortunate event that you have no idea about a particular case or question raised, say: 1. Your Honour, I am afraid I cannot assist the Court on that point but then link this to something YOU DO KNOW!;.or 2. Your Honour, I am afraid I cannot assist the Court on that point (less preferable better to segue into a point you do know something about!) Answering Questions The interaction between a judge and a mooter is one of the most challenging but most enjoyable aspects of mooting.

Aim of the Judge in asking the question To test the strength of the argument To test the knowledge of the mooter To test the mooters resolve and style under pressure

Aim of the Mooter in answering the question To engage in a conversation with the bench To demonstrate the depth and breadth of research and argumentation To clarify the argument or correct a misconception To show a bit of personality

Different types of questions and how to deal with them Type of Question Clarifications about the facts, your submissions or the law How to deal with the question Clarification questions seek the quick supply of information to supplement what the judge already knows You deal with them as quickly as you can (while giving a full answer)

12

Judge usually wants to follow up this question with another, more substantive question NB: You can avoid being asked these questions by being clear up front. These are designed to test your knowledge about the case/statutes/treaties/etc Also designed to test how apposite the authority is Again the judge usually follows up this question another, more substantive question This is a great chance to show off your knowledge Questions intended to aid you/your submissions Judges will sometimes ask you questions that help develop your submission - not all questions are attacks on your argument! Recognise a helpful statement or query from the judge Yes, Your Honour correctly states the position I am advancing but avoid being too obsequious (phrases like I am grateful for your Honours question, which perfectly states my case might be overdoing it a bit) Questions that posit an alternative argument These test mooters ability to think on their feet May reflect what is in the bench memorial You should investigate the alternative argument, and satisfy the Judge, but always look for a segue back into your own submissions (presuming they are correct, of course!) Try to show how alternative arguments

Questions about authorities

13

Questions designed to lead you up the garden path

achieve the same result as your argument. Questions may be designed to lead you up the garden path. If the question is tangential, it may be intentionally so that is, the Judge is testing your ability to segue back into your own submissions. Alternatively, it may be that judge is ignorant and it is unintentionally tangential - the challenge here is to get back to your own submissions. It can be tough going - you need to: - Realise its happening- its easy to get caught up in the moment - Look to distinguish the tangent from what you say is the crux of the case - Then neatly move to explain the crux of the case - and hey presto! you are back on your prepared submissions Common trick is for a judge to ask for submission 2 before submission 1. This is mainly to test how you cope with the shock of re-arranging the order of your submissions on your feet. Be sure to maintain your case theory (eg: if taken to merits before jurisdiction, still remember: Your Honour, subject to our submission on jurisdiction, we say)

Questions that disrupt the order of the submissions

Developing good advocacy technique Good advocacy requires not only that you follow the structure outlined above, but also that you master several other aspects of how you deliver your case. There is no one type of advocacy but here are some useful pointers: Focus on the critical differences between the parties: it is essential that you are aware of the central disputes in the case. This is what the majority of your time should be allocated to. Everything you say should either explicitly or at least by implication refute the other sides arguments. One exception to this tip is during question answering - address whatever the judge asks for, but make sure you return to the central differences between you and the other side. For example, a common error for new mooters is to re-state the legal test already stated by their opponent if the appellant and respondent do not disagree on the law, but merely the application of the law to the particular facts, then say so: Your Honour, my learned friend has already 14

stated the legal test as expounded in Case X, with which we agree. The crucial difference between the parties in this case is how to apply that test to these facts. We submit, contrary to the appellants, that the rule in Case X means[the crucial point!] Order submissions logically - this will help you and the Judge. For example, address any issue of jurisdiction or standing before turning to the merits of the matter. Argue persuasively both on the law and on the facts: a good advocate goes beyond stating the law or the facts and posits arguments as to why those laws or facts support their arguments. Be clear and concise. Avoid words that are a red flag to the judge o The circumstances might indicate that the plaintiff was intoxicated compared to The respondent submits that the reasonable inference is that the plaintiff was intoxicated. o State practice generally seems to support this rule that compared to It is a rule of customary international law, supported by state practice, that o It could be concluded vs it can be concluded o The facts suggest vs the facts show o In short: make assertions, be confident, and dont prevaricate: judges can smell fear! You must adopt a position on the law or facts in circumstances where they are ambiguous (but, if the facts are ambiguous, this is NOT a license to invent new facts. You can proffer explanations for why certain facts might exist, but ultimately if the problem question doesnt say so, you cant assert it. For example, if, in a contract case, two parties agree on a construction contract for what is stated in the problem as a ridiculously low price, and the judge asks you Why did your client agree to such a low price?, you have to be honest and say The record doesnt indicate why my client did so, Your Honour. Possible reasons may be that she knew the contractor, or was unaware of a reasonable retail price, but ultimately we do not know. This proffers AN explanation, without INVENTING facts.) Know the limits of your argument and the effect of findings against you (including the implications for your co-counsel). Identify your strong from your weak arguments

As for the appropriate manner in the moot court, here are some useful guidelines: Be deferential but natural Show flexibility and enthusiasm Strive for clarity - put your argument as succinctly as possible and avoid verbiage o Compare It will be submitted by the respondent that vs the respondent submits o The submission of the applicant on that point is vs the applicant submits

15

Know court etiquette, such as proper appellations: you say Justice Kirby rather than Kirby J; address the judge as Your Honour, address a full bench as the Court (subject to exceptions in international law moots, on which see below).

Case Citation It is important to know how to read out a court citation in a moot. Here are some examples: Royall v R (1991) 172 CLR 1: 1. Initial Citation (ie the first time you mention the case): Royal against the Queen, reported in 1991 at volume one hundred and seventy two of the Commonwealth Law Reports at page 1 2. Subsequent citations: Royall against the Queen or Royall Waltons Stores (Interstate) Ltd v Maher (1988) 164 CLR 387 at 404 1. Initial citation: Waltons stores interstate limited and Maher, 1988, volume 164 of the Commonwealth Law Reports at page 404 2. Subsequent citations: waltons stores and maher NOTE: In civil cases, the v means and BUT in criminal cases it means against.

Public International Law Moots (Distinguishing Features)

There are some specific features of etiquette and citation unique to public international law moots: Addressing the court If you are before the International Court of Justice (ICJ), you refer to the judges as Your Excellency (not your honour). If you have a panel of 3 judges, the Judge in the middle of the panel (or otherwise nominated, if you have 2 judges) is the President of the Court, and should be addressed as such. If male, Mr President; if female, Madam President. So, for example, in giving your appearances you would say Mr President, Your Excellencies, my name is Ms Morris and I appear with my co-agent, Ms Murray, for the Applicant, the Kingdom of Arkam. Note that counsel are referred to as agents before the ICJ. Citations Note that there is no doctrine of precedent in the ICJ however, the practice of the Court is that it does refer to its earlier judgments, or judgments of its predecessor,

16

the Permanent Court of International Justice (PCIJ). Such judgments are considered persuasive. Other than ICJ/PCIJ cases, other likely sources you will need to cite include treaties or the writings of publicists. (On the sources of law before the ICJ, see Article 38(1) of the Courts Statute). The following provide examples of proper written citations, followed by indications of how to read them out to the Court: Military and Paramilitary Activities in and against Nicaragua (Nicaragua v USA) (Merits) [1986] ICJ Rep 14 1. Initial citation: the case concerning military and paramilitary activities in and against Nicaragua, Nicaragua and United States of America, Merits phase, as reported in the 1986 ICJ Reports starting at page 14 2. Subsequent citation: the Nicaragua case International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, opened for signature 16 December 1966, 999 UNTS 171 (entered in force 23 March 1976) 1. Initial Citation: the 1966 international convenant on civil and political rights, in volume 999 of the United Nations Treaty Series at page 171 (it is a good idea to also know when a treaty entered into force, and how many states parties there currently are to it a judge will often ask this) 2. Subsequent citation: the Covenant or the ICCPR (it is a good idea after the initial citation to say hereafter referred to as the Covenant, and thereby define your shorhand terminology) Ambatielos Arbitration (1956) 12 RIAA 83 Initial Citation: the Ambatielos Arbitration of 1956 in volume 12 of the UN Reports of International Arbitral Awards at page 83 (note here that you would need to know who decided the case was it one adjudicator? An arbitral tribunal? Each arbitration is different.) BROWNLIE, Principles of Public International Law (6th ed., 2003) Citation: as stated by Professor Ian Brownlie in the 6th edition of his treatise, the Principles of Public International Law, from 2003 (note, if you are citing publicists, you must also know who they are professor of what, at which institution? For example, if pressed who is Ian Brownlie? you would say Professor Brownlie was the Chichele Professor of Public Intenrational Law at the University of Oxford from 1980 to 1999 and a member of the International Law Commission from 1997 to 2008. You have to prove the credentials of the publicists you rely on.)

17

You might also like

- Guide to Mooting SkillsDocument32 pagesGuide to Mooting SkillsSatya100% (1)

- Moot PDFDocument24 pagesMoot PDFharsha chandrashekarNo ratings yet

- Moot Court - AdvantagesDocument11 pagesMoot Court - AdvantagesAbhishek CharanNo ratings yet

- How To Research For MootDocument16 pagesHow To Research For MootSneha SinghNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court of Wisconsin Rules in Vosburg v. Putney on Liability for Unintended Consequences of Intentional ActsDocument7 pagesSupreme Court of Wisconsin Rules in Vosburg v. Putney on Liability for Unintended Consequences of Intentional ActsSasi KumarNo ratings yet

- 2017 Mooting GuidelinesDocument8 pages2017 Mooting GuidelinesjohnNo ratings yet

- Civil Courts and Constitutional IssuesDocument7 pagesCivil Courts and Constitutional IssuesAbdul Samad ShaikhNo ratings yet

- Rules of Court OutlineDocument28 pagesRules of Court OutlineCarel Brenth Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- How to Ace Law School ExamsDocument6 pagesHow to Ace Law School ExamsMelvin PernezNo ratings yet

- Canadian Family Law CasesDocument3 pagesCanadian Family Law CasesgenNo ratings yet

- Legitimacy in Private International Law by Soumik Chakraborty 629Document17 pagesLegitimacy in Private International Law by Soumik Chakraborty 629Gokul RungtaNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law Study UnitsDocument52 pagesCriminal Law Study UnitsJackson Loceryan100% (1)

- Kinds of ArbitrationDocument4 pagesKinds of ArbitrationNitish GuptaNo ratings yet

- Unconstituionality of LEB Memos For Law StudentDocument1 pageUnconstituionality of LEB Memos For Law StudentDuko Alcala EnjambreNo ratings yet

- Conflict of LawsDocument31 pagesConflict of LawsGloria KovačevićNo ratings yet

- All Cover Letters Web 2011Document18 pagesAll Cover Letters Web 2011Ahmed Maged100% (1)

- IP Law Syllabus Prof LazaroDocument1 pageIP Law Syllabus Prof LazaroChristopher JavierNo ratings yet

- Plea BargainingDocument12 pagesPlea BargainingHardeep SinghNo ratings yet

- LSUC Assessment Questions and AnswersDocument11 pagesLSUC Assessment Questions and AnswersNate FannNo ratings yet

- How To Write Law Exams (S.I Strong) )Document28 pagesHow To Write Law Exams (S.I Strong) )SSSNo ratings yet

- Mya's Winter Criminal Law SummaryDocument143 pagesMya's Winter Criminal Law SummaryKeethu RaveendranNo ratings yet

- Important Case Laws on Contempt, Compensation & Dowry DeathDocument24 pagesImportant Case Laws on Contempt, Compensation & Dowry DeathAshmika RajNo ratings yet

- Nature of International Law and SourcesDocument84 pagesNature of International Law and Sourcesuokoroha100% (1)

- Trial Advocacy 2015 PDFDocument97 pagesTrial Advocacy 2015 PDFPaul Hontoz86% (7)

- Love Thy Neighbor, Barangay Legal Aid Free Information GuideFrom EverandLove Thy Neighbor, Barangay Legal Aid Free Information GuideNo ratings yet

- ADR NOTES Class DiscDocument14 pagesADR NOTES Class DiscDave A ValcarcelNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Law International Law Bankruptcy: Further ReadingsDocument6 pagesConstitutional Law International Law Bankruptcy: Further ReadingsAnkur JainNo ratings yet

- Adversarial v. InquisitorialDocument4 pagesAdversarial v. InquisitorialnikitaNo ratings yet

- Civil Law Review CasesDocument165 pagesCivil Law Review CasesLois DNo ratings yet

- Criminal Procedure Outline 2021Document4 pagesCriminal Procedure Outline 2021Ry ChanNo ratings yet

- Understand Legal Analysis with IRACDocument22 pagesUnderstand Legal Analysis with IRACAlexine Ali BangcolaNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law CasesDocument104 pagesCriminal Law CasesBelen Aliten Sta MariaNo ratings yet

- Notice of Intention To Sue - Medical InternsDocument1 pageNotice of Intention To Sue - Medical InternsTheCampusTimesNo ratings yet

- CONFFESSION EvidencelawDocument13 pagesCONFFESSION EvidencelawShahbaz MalbariNo ratings yet

- GAL Erica Wikstrom's Retaliation Motion Re SoderlundDocument8 pagesGAL Erica Wikstrom's Retaliation Motion Re SoderlundJournalistABCNo ratings yet

- Persons 10Document9 pagesPersons 10Rodney UlyateNo ratings yet

- Mooting The Definitive GuideDocument285 pagesMooting The Definitive GuideAkshata Sawant100% (1)

- Legal Writing 201Document26 pagesLegal Writing 201Mayette Belgica-ClederaNo ratings yet

- Alberta Rules of CourtDocument763 pagesAlberta Rules of CourtJohn Henry Naga100% (1)

- Interpretation of Statutes and General Clause ActDocument5 pagesInterpretation of Statutes and General Clause ActAyushk5No ratings yet

- Hidayatullah National Law University, New Raipur Jurisprudence - II B.A.LL.B. (Honours) VI SemesterDocument5 pagesHidayatullah National Law University, New Raipur Jurisprudence - II B.A.LL.B. (Honours) VI SemesterDivy DurgeshNo ratings yet

- Character Reference for Brother's Drug ChargeDocument1 pageCharacter Reference for Brother's Drug ChargeShiredan Rose BagarinaoNo ratings yet

- 20 Winter 2014 - FinalDocument21 pages20 Winter 2014 - FinalVanessa HaliliNo ratings yet

- Revised Civil Procedure 2020 (Amendments Only)Document107 pagesRevised Civil Procedure 2020 (Amendments Only)red_inaj0% (1)

- Case Brief WorksheetDocument18 pagesCase Brief Worksheetverair100% (2)

- Legal Citation GuideDocument36 pagesLegal Citation GuideKristine DizonNo ratings yet

- Conflict of Laws and Choice of LawDocument30 pagesConflict of Laws and Choice of Lawlegalmatters100% (6)

- Guide To Legal Research and WritingDocument16 pagesGuide To Legal Research and WritingAman SinghNo ratings yet

- Conflict of Laws Syllabus 2017Document2 pagesConflict of Laws Syllabus 2017sara100% (1)

- Course Contents: Civil LitigationDocument30 pagesCourse Contents: Civil LitigationAyo Fasanmi100% (1)

- January 2020 Exams Required ReadingsDocument2 pagesJanuary 2020 Exams Required ReadingsClarissa D'AvellaNo ratings yet

- Comparing International Trade TheoriesDocument7 pagesComparing International Trade TheoriesnivebalaNo ratings yet

- Torts Problem Solving GuideDocument25 pagesTorts Problem Solving GuideAlfred WongNo ratings yet

- Moot CourtDocument9 pagesMoot CourtVanshika GaurNo ratings yet

- University of Sydney Faculty of Law LEGAL WRITINGDocument18 pagesUniversity of Sydney Faculty of Law LEGAL WRITINGMaksim K100% (2)

- Case AnalysisDocument3 pagesCase AnalysisAryan Xworld007No ratings yet

- Moot Courts and Mooting RulesDocument9 pagesMoot Courts and Mooting Rulespranjal chauhan100% (1)

- What Is Mooting and How Is It Done?: Moot CourtDocument4 pagesWhat Is Mooting and How Is It Done?: Moot CourtVivek PandeyNo ratings yet

- How To Study and Answer Case Type QuestionsDocument4 pagesHow To Study and Answer Case Type QuestionsG MadhaviNo ratings yet

- What Is MootingDocument3 pagesWhat Is MootingBeboy Paylangco EvardoNo ratings yet

- Course 03: Comparative Public Law - History and Development of International Investment TreatiesDocument21 pagesCourse 03: Comparative Public Law - History and Development of International Investment TreatiesKashish ChhabraNo ratings yet

- International Law - 1950 PDFDocument398 pagesInternational Law - 1950 PDFhanna gabrielleNo ratings yet

- Question Papers 6 Sem Delhi University LL.BDocument369 pagesQuestion Papers 6 Sem Delhi University LL.BIshaan HarshNo ratings yet

- Klabbers, Jan - The Right To Be Taken Seriously. Self-Determination in International LawDocument22 pagesKlabbers, Jan - The Right To Be Taken Seriously. Self-Determination in International LawRoberto SagredoNo ratings yet

- Module-3-The Contemporary WorldDocument19 pagesModule-3-The Contemporary WorldJunesse BaduaNo ratings yet

- The Compulsory Jurisdiction of The International Court of Justice: How Compulsory Is It?Document10 pagesThe Compulsory Jurisdiction of The International Court of Justice: How Compulsory Is It?Huzaifa saleem 2No ratings yet

- UNITED NATIONS JURIDICAL YEARBOOK 1992 Part Four.Document62 pagesUNITED NATIONS JURIDICAL YEARBOOK 1992 Part Four.mary engNo ratings yet

- PDF Bar Questions On Public International Law - CompressDocument8 pagesPDF Bar Questions On Public International Law - CompressPrime Dacanay100% (1)

- 3.mills - JurisdiccionDocument53 pages3.mills - JurisdiccionBrigitte RyszelNo ratings yet

- SLASLEC-May 2016Document22 pagesSLASLEC-May 2016Joseph MainaNo ratings yet

- ICJ - Asylum Case (Colombia V Peru) 1950 Judgment For InterpretationDocument1 pageICJ - Asylum Case (Colombia V Peru) 1950 Judgment For InterpretationRem RamirezNo ratings yet

- Territorial DisputesDocument3 pagesTerritorial DisputesVarun OberoiNo ratings yet

- International Court of Justice Rules on Barcelona Traction CaseDocument93 pagesInternational Court of Justice Rules on Barcelona Traction CaseRichesa Kyle R. CarandangNo ratings yet

- The Need To Amend Article 38 of The Statue of The International Court of JusticeDocument11 pagesThe Need To Amend Article 38 of The Statue of The International Court of JusticeGlobal Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet

- CARRASCOSA v. MCGUIRE - Document No. 25Document20 pagesCARRASCOSA v. MCGUIRE - Document No. 25Justia.comNo ratings yet

- Respondent MemorialDocument25 pagesRespondent MemorialMH MOHSINNo ratings yet

- Nuclear Test Case (Digest)Document2 pagesNuclear Test Case (Digest)KathrinaFernandezNo ratings yet

- The Creation of Jus Cogens - Making Sense of Article 53 of The Vienna ConventionDocument20 pagesThe Creation of Jus Cogens - Making Sense of Article 53 of The Vienna ConventionZeesahnNo ratings yet

- Transcribed Candelaria Lecture in Public International LawDocument62 pagesTranscribed Candelaria Lecture in Public International LawLaurice Claire C. Peñamante33% (3)

- Definition of Terrorism in UN Security Council 1985-2004Document26 pagesDefinition of Terrorism in UN Security Council 1985-2004I.G. Mingo MulaNo ratings yet

- AIM 2018 Moot Problem PDFDocument11 pagesAIM 2018 Moot Problem PDFSimranNo ratings yet

- International Court of JusticeDocument14 pagesInternational Court of JusticeNoli Llanera100% (1)

- 4Th Nuals Maritime Law Moot Court Competition, 2017: in The Permanent Court of ArbitrationDocument27 pages4Th Nuals Maritime Law Moot Court Competition, 2017: in The Permanent Court of ArbitrationAarif Mohammad BilgramiNo ratings yet

- BOOK - The Right To Reparation in International Law For Victims of Armed Conflict PDFDocument298 pagesBOOK - The Right To Reparation in International Law For Victims of Armed Conflict PDFasfdaf9asdfafsafNo ratings yet

- Applicant MemorialDocument39 pagesApplicant Memorialaryan88% (17)

- Case Concerning Maritime Delimitation and Territorial Questions Between Quatar 1994-2001Document4 pagesCase Concerning Maritime Delimitation and Territorial Questions Between Quatar 1994-2001Nikka Razcel GloriaNo ratings yet

- Public International LawDocument114 pagesPublic International LawAurora Esterlia100% (4)

- Memo Petitioner FinalDocument37 pagesMemo Petitioner FinalArpitNo ratings yet

- General Contract Conditions IIDocument5 pagesGeneral Contract Conditions IIaslindawidiyanti3008No ratings yet

- Formation of The League of Nations Was Unique, Though It Failed, Yet League Has Enormous Effect Over The Future International OrganizationDocument12 pagesFormation of The League of Nations Was Unique, Though It Failed, Yet League Has Enormous Effect Over The Future International OrganizationHimanshu BhatiaNo ratings yet